Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Verbum et Ecclesia

On-line version ISSN 2074-7705

Print version ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.38 n.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v38i1.1650

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The preliminary urban missionary outreach of the apostle Paul as referred to in Acts 13-14

Muthuphei A. Mutavhatsindi

Department of Science of Religion and Missiology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The objective of this article is to deal precisely and systematically with the preliminary urban missionary outreach of the apostle Paul as referred to the book of Acts, chapters 13-14. This article covers an ample spectrum of Paul's mission work together with his companions. The book of Acts gives us a full exposition of the Holy Spirit as the primary agent of mission. The Holy Spirit led the church in Antioch of Syria in the dedication of Paul and Barnabas for their mission work which was specifically to the Gentiles as the Jews who were given the first preference rejected the Gospel (Ac 13:46). Christ in Acts 9:15 indicated his intention of choosing Paul as his chosen vessel to bear his name before the Gentiles, and kings, and the children of Israel, and this commission of Paul to the Gentiles was also referred to in Acts 22:21. The result of the apostles' propagation of the Word of God was that many Gentile people from different cities repented and became Christians. Although the apostles encountered many challenges and opposition, their initial campaign ended in a good mode, as they experienced the wonderful works of God to the Gentiles as God had opened a door of faith (salvation) among the Gentiles.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: This article deals with missiological issues as it refers to Paul, who together with his crew encountered many challenges in their mission work like an opposition, expulsion, exaltation, stoning and so on. Even though they faced those challenges, they did not evacuate their responsibility of propagating the Word of God in different metropolitan areas. Thus where the element of 'perseverance of the saints' of the Reformed Dogmatics comes in.

Introduction

The two chapters of the book of Acts (chapters 13-14) recount Paul's first missionary outreach. The efforts of spreading the Gospel of the Kingdom of God to the Gentiles did not occur without conflict and suffering, as can be seen from the narrative flow of the material. According to Spencer (1997:131), each of the above two chapters (Ac 13-14) is divided into three units. The opening and closing scenes record Paul's commission in and return to the city of Antioch. In between, each scene is marked by conflict and, in some cases, violence. Paul's ministry begins with a contest with the Jewish sorcerer, Elymas, in Cyprus. His preaching in the city of Pisidia results in his expulsion from the region (Allen 2006:62). Nearly stoned in Iconium, he is stoned and left for dead in the city of Lystra. At Paul's conversion, God says that Paul is going to be his instrument of carrying the Gospel to the Gentiles and he would suffer for Jesus' name (Ac 9:15-16), and this preliminary campaign is the narrative fulfilment of that prophecy (Parsons 2008:181).

Commissioning of Paul and Barnabas at the city of Antioch

The book of Acts chapter 13 begins with the commissioning of Paul and Barnabas by the church at Syrian Antioch under the influence of the Holy Spirit (13:1-3) (Krodel 1981:47; cf Goheen 2000:183). The importance of the Christian community at Antioch has already been noted at Acts 11:19 which says:

Now those who had been scattered by the persecution that broke out when Stephen was killed travelled as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch, spreading the word only among Jews.

For Parsons, 'the leadership of this congregation consists of teacher-prophets, who give Spirit-inspired exhortation and instruction' (Parsons 2008:184). Parsons (2008:184) further indicates that the prophets from Antioch had already been mentioned at Acts 11:27, and through this is the first mention in Acts of 'teachers', the verb 'teach' occurs frequently in the book of Acts (for instance: 1:1; 4:2, 18; 5:21, 25, 28, 42; 15:1, 35; 18:11, 25; 20:20; 21:21, 28; 28:31), most notably at Acts 11:26, in which Barnabas and Paul are depicted as teaching the congregation residing in the city of Antioch.

There are two things which are noteworthy about the list of five prophet-teachers given in Acts 13:2-3 (Schnabel 2008:74). The diversity of the church in the city of Antioch is evidenced by this short list. Barnabas is already familiar to the audience as a Levite and native of Cyprus (Ac 4:36). Like Joseph, Barsabbas was called Justus (Ac 1:23), and John called Marcus (Ac 12:12), Simeon is another Jewish Christian with a Latin surname, Niger (Johnson 1992:220). 'Niger' is the Latin name for 'black', and it is possible this Simeon was from the North Africa (Barrett 1994:603). Lucius is originally from Cyrene and perhaps among those broad-minded enough to evangelize among the Gentiles (Ac 11:20). Manaen was of aristocratic Jewish stock, having been brought up in the court of Herod Antipas (Lk 3:1; Ac 4:27 and comments on Ac 11:27-30). Members of this group of prophet-teachers, rounded out by Saul of Tarsus, are no less diverse in their social and economic backgrounds than were the Twelve disciples whom Jesus originally called.

According to Fitzmyer (1992:41), the second important feature is the role of the Holy Spirit in the commissioning of Paul and Barnabas. 'While they were worshipping the Lord and fasting, the Holy Spirit said, "Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them"' (Ac 13:2) (Schnabel 2008:74). Those who were worshiping the Lord and fasting could refer either to the aforementioned leaders (Barrett 1994:604), but more probably refers to the larger Antioch congregation (Polhill 1992:290), since in other situation the entire community ratifies decisions (Ac 1:15; 6:2, 5; 14:27; 15:22) (Krodel 1981:228).

Luke wants to make it clear that just as the Holy Spirit was involved at the beginning of the public ministry of both Jesus (Lk 3) and the apostles (Ac 1), the church in Antioch sets Saul and Barnabas apart under the direction of the Holy Spirit (Ac 13:2) (Bavinck 1960:280; Johnson 1987:53; Schnabel 2008:74). For only the third time in the book of Acts (8:29; 10:19), the Holy Spirit is depicted as speaking in direct discourse as a character in the narrative (Skreslet 2006:50), as opposed to other characters reporting what the Holy Spirit said (Ac 11:12; 21:11) or the narrator reporting that the Holy Spirit spoke through someone else (Ac 21:4) (Krodel 1981:68):

Earlier the Holy Spirit had spoken directly to an individual (Philip and Peter, while in a trance); for the first (and only) time in Acts, the Holy Spirit here speaks to a group in a direct discourse. (Parsons 2008:185)

The work for which Paul and Barnabas are to be set apart recurs at the end of the missionary journey when they return to Antioch to be commended for the work that they had completed. 'From Attalia they sailed back to Antioch, where they had been committed to the grace of God for the work they had now completed' (Ac 14:26). References to 'work' then forms an inclusion to this unit (Polhill 1992:290) and events recorded in between in two chapters (13-14) of the book of Acts clarifying that this work is related to the opening of 'a door of faith for the Gentiles' (Ac 14:27) (Schnabel 2008:89). That Paul and his company have been divinely called to perform this 'work' of the Gentile mission will later be reinforced by the reference in Acts 16:10 that Paul and his companions sought to cross over to Macedonia, convinced that God had called them to proclaim the Good News to the residents of Macedonian Philippi and Thessalonica.

The response of the believers of the church in Antioch to the command of the Holy Spirit

The Antioch believers respond with three actions before sending Paul and Barnabas to fulfil their work: they fasted, prayed and laid their hands on them (Ac 13:3a). Prayers and fasting are common expressions of Jewish (Neh 1:4; Jr 14:12; Mt 6:5, 16) and Christian piety (Johnson 1992:221). While corporate prayer is quite common in Acts (1:24; 6:6; 8:15; 12:12; 14:23; 21:5), there are only three references to fasting, two in Acts 13:2-3 and one in Acts 14:23 (Krodel 1981:54). All three refer to the church at Antioch fasting in connection with the appointment of church leaders. The church that selflessly gave to relieve fasting imposed by famine (Ac 11:27-30) now engages in fasting for religious purposes. Finally, the church in Antioch laid their hands on Paul and Barnabas, a gesture of transmitting authority (Ac 6:6; 8:17-19; 9:17) (Fitzmyer 1989:14). This laying on of hands reminds one of God's instructions to Moses for the laying on of hands for the Levite priests in Numbers 8. In the case of Acts 13, it is the authority of Holy Spirit who sent Paul and Barnabas to undertake the work associated with the Gentile mission (Mutavhatsindi 2008:25). Though other Gentiles like the Ethiopian1 eunuch and the household of Cornelius2 had converted already to Christianity, and while Paul and Barnabas would regularly proclaim the Christian message in Jewish synagogues, here in Acts 13:1-3 they are commissioned to the full-time and intentional pursuit of the Gentile mission (Schnabel 2008:74; cf. Horrell 2004:34). For Tannehill, the commissioning of Paul and Barnabas echoes the beginning of the missions of both Jesus and the apostles (Paul & Barnabas 1990:161). Like the mission of Jesus and the apostles, the mission of Paul and Barnabas is preceded by prayer (Ac 13:2a; cf. Lk 3:21; Ac 1:14) and directed by the Holy Spirit (Ac 13:2b; cf. Lk 3:22; Ac 2:1-4). 'Fasting is also an important element in the preparation for Jesus' mission (Lk 4:1-2; cf. Ac 13:1, 3), though it is missing from the apostles' mission' (Parsons 2008:186).

As his strategy, Paul concentrated on the district or provincial capitals, each of which stands for a whole region (Bosch 1991:130). For David Bosch, these 'metropolises' are the main centres as far as communication, culture, commerce, politics and religion are concerned (1991:130). Paul frequently speaks of his mission as being directed towards various countries and geographical regions (Gal 1:17, 21; Rom 15:19, 23, 26, 28; 2 Cor 10:16) (Bosch 1991:130; cf. Hultgren 1985:133). The two apostles Paul and Barnabas were faithfully dedicated to the work assigned to them by the Holy Spirit, and they propagated the Word of God in many cities like Cyprus, Pisidia, Iconium and so on. 'The cities were where power was. They were also the places where changes could occur' (Meeks 1983:15). The cities which figured prominently in Paul's ministry were centres of administration, centres of Greek culture, even centres of Jewish influence and centres of commerce and trade (Dubose 1978:46).

Contest encountered by the apostles in the city of Cyprus

The two apostles Paul and Barnabas are sent out by the Holy Spirit after their commissioning, and they went down to Seleucia and from there sailed to Cyprus (Fitzmyer 1992:41). It is conceivable that Paul and Barnabas had planned the new missionary initiative with the goal of reaching Cyprus for some time (Schnabel 2008:75). The passage begins with the emphatic use of the personal pronoun 'they' drawing attention to the identity of Barnabas and Paul without naming them. The area of Cyprus is not new to Barnabas, it is familiar ground for him, who was a native of that island (Ac 4:36), as well as for the audience who knew that Christian missionaries had already been there (Ac 11:19). Fitzmyer further indicates that the apostles visited the established churches in Salamis and they proclaimed the message of God in the Jewish synagogues (Ac 13:5a) (Fitzmyer 1992:38). Salamis was a port city on the eastern coast of Cyprus, and here the two engage in a practice that would characterise the rest of Paul's missionary career; they preached the Word of God in the synagogues of the Jews (see Ac 13:14; 14:1; 17:1, 10, 17; 18:4, 19; 19:8) (Parsons 2008:186). The extensive time Paul spent with the Jews is to show that because the Jews reject the Gospel, then Paul is forced to take it to the Gentiles. During that time, they had John Mark as their assistant when they preached to the Jews in Salamis (Black 1998:243; cf. Fitzmyer 1989:14; Schnabel 2008:74). When Christians do mission work, sometimes they encounter strong opposition and rejection of the Gospel and they have to be bold and defend the Gospel. For instance, when Paul and Barnabas together with John Mark traversed the length of the island to Paphos on the other coast, they found a magician and Jewish false prophet, by the name of Bar-Jesus (Ac 13:6) (Fitzmyer 1989:14). This man Bar-Jesus was in the service of a leading Roman official Sergius Paulus, described here as a proconsul (Schnabel 2008:43). The proconsul was an intelligent man and summoned Paul and Barnabas because he wanted to hear the Word of God, but Elymas the sorcerer opposed them and tried to turn the proconsul from the faith. Paul who was totally disturbed by the bad behaviour of Elymas was filled with the Holy Spirit, looked straight at him and says:

You are a child of the devil and an enemy of everything that is right! You are full of all kinds of deceit and trickery. Will you never stop perverting the right ways of the Lord? Now the hand of the Lord is against you. You are going to be blind for a time, not even able to see the light of the sun. (Ac 13:10-11)

Paul's invective leads to his curse of blindness on Elymas: 'Now the hand of the Lord is against you. You are going to be blind for a time, not even able to see the light of the sun' (Ac 13:11) (Krodel 1981:47). This was an especially fitting curse: as an idolater who serves as an agent of Satan, Elymas is cursed to the darkness from which he has come. For Garrett (1989:82-83), the curse echoes Deuteronomy 28:28-29, in which Moses gives a list of punishments that await the Israelites who forsake Yahweh for idolatrous allegiance to other gods:

The LORD will afflict you with madness, blindness and confusion of mind. At midday you will grope about like a blind person in the dark. You will be unsuccessful in everything you do; day after day you will be oppressed and robbed, with no one to rescue you.

What happened to Elymas? 'Immediately mist and darkness came over him, and he groped about, seeking someone to lead him by the hand' (Ac 13:11). The point of this scene for the ministry of Paul is crucial: like Jesus, Paul has demonstrated his authority over the forces of Satan and thus has proven himself worthy of the mission set before him. The scene concludes with the purpose of leading Elymas who was strongly opposed to the Word of God to blindness: 'When the proconsul saw what had happened, he believed, for he was amazed at the teaching about the Lord' (Ac 13:12) (Fitzmyer 1989:14). From the above scenario, we learn two things: it is clear that God punishes people who become stabling block to the conversion of others and, lastly, God sometimes uses his punishment to those who oppose his Word to bring others to repentance.

Preaching and expulsion of the apostles in the city of Pisidia

The section dealing with the preaching of the apostles and also their expulsion from the city of Pisidia is well illustrated in Acts 13:13-52. This scene has three parts which are as follows: the setting (13:13-15), the speech (13:16-41) and the aftermath (13:42-52). Here, I will elucidate each of these three parts.

The setting

After a whistle stop in Perga, Paul and his company come to Antioch of Pisidia (Fitzmyer 1992:41). Not all of Paul's companions continue with him: but John deserted them and returned to Jerusalem (13:13b); regarding the translation that John 'deserted them', this is commented in Acts 15:36-41. Paul and the rest of his company continue on to Antioch in Pisidia. They went into the synagogue on the Sabbath day. According to Parsons (2008:191), after the reading of the Law and Prophets (Ac 13:15; cf. Lk 4; Ac 15:21), the leaders of the synagogue (cf. Lk 8:41, 49; 13:14; Ac 18:8, 17) invite Paul to speak a word of encouragement (cf. Heb 13:22). Paul then delivers the first of his three major missionary addresses in Acts (cf. Ac 17:22-31; 20:18-35).

Paul's speech in the Jewish synagogue

According to Roger E. Hedlund, Paul's first approach in most of the centres was to the synagogue, to the people of the covenant found in Acts 13:5, 14; 14:1; 17:1-2, 10; 18:4, 19. They were the prepared people (1985:217). Like Jesus in the synagogue in Nazareth (Lk 4:16-30), Paul and Barnabas were invited to speak in the Jewish synagogue (Krodel 1981:48). While in the synagogue, Paul stood up, motioned with his hand,3 and spoke (Ac 13:16a). Parsons suggests that the posture and gestures are typical of speakers in Acts: on standing to speak (Ac 1:15; 5:34; 6:9; 11:28; 15:5, 7; 23:9; 25:18; 27:21) and on waving the hand (12:17; 13:16; 19:33; 21:40; 26:1) (Parsons 2008:191). The gestures, however, may not all carry the same meaning in each instance, nor may the lector has been expected to use the same motion (Shiell 2004). In Acts 12:17, Peter gestures to silence an amazed crowd; in Acts 13:16, Paul signals to alert the audience that a word of exhortation is about to commence, using a particular gesture expected (Shiell 2004:145-148).

Paul's introduction is very brief, 'Fellow Israelites and you Gentiles who worship God, listen to me!' (Ac 13:16b). Paul addresses his audience as 'Israelites' which literally means 'men, Israelites', a similar greeting is used elsewhere in the book of Acts (2:22; 7:2; 15:13; 22:1; 26:3). The other group addressed by Paul, the God-fearers (cf. Ac 10:2), is mentioned again in Acts 13:26 and may be taken to be identical to the 'devout converts to Judaism' mentioned in Acts 13:43, both signifying in a non-technical way Gentiles who had aligned themselves with the worship and practices of the Jewish synagogue.

According to Krodel, the second part of Paul's speech, the narratio in Acts 13:17-25, is similar to Stephen's speech in that it recounts Israel's history; its emphasis, however, differs by focusing not on Israel's rebelliousness but rather on God's faithfulness (Krodel 1981:48). It is very important to compare the two speeches (of Paul and of Stephen) because they all highlight the basic doctrine of the Israel's history, although the way they laid out this history in some instances differ in one way or another, but the most important is that they all highlighted it as an important background that should be understood by the people. In fact, the first words of this part of the speech are 'the God of this people Israel' (echoing the epithet 'God of Israel', familiar from the Greek translations of Psalms 40:40; 58:6; 67:8, 35; 68:9; 71:18; cf. Lk 1:68). God is the subject of most of the verbs in this section: God 'chose' (Ac 13:17); God 'made' them 'a great people' (Ac 13:17b; God 'led them out' (Ac 13:17c); God 'put up with them' (Ac 13:18); God 'overthrew' seven nations in the land of Canaan (Ac 13:19a); God 'gave their land' (Ac 13:19b); God 'provided' them judges (Ac 13:20); God 'gave' them Saul (Ac 13:21); God 'removed' Saul (Ac 13:22); God 'raised up David to be their king' (Ac 13:22b); God 'spoke' (Ac 13:22); and God 'brought' (Ac 13:23). In addition, several of these verbs are used elsewhere of divine activity: to choose (Ac 13:17; cf. 1:24b-25), to make great (Ac 2:33; 5:31) and to lease out (Ac 7:40).

The divine activity described by Paul moves from the exodus to the enthronement of David. Paul's description of that segment of Israelite history at the discourse level is instructive. He begins, 'The God of the people of Israel chose our ancestors; he made the people prosper during their stay in Egypt; with mighty power he led them out of that country' (Ac 13:17). The reference to 'this people Israel' strikes several familiar Lukan themes. The name 'Israel' occurs three times in Paul's speech (in Ac 13:17 as well as in 13:23; 24) as it does in Stephen's speech (Ac 7:23, 37, 42) (Johnson 1992:230).

The events are telescoped in Paul's reference to God's choosing the 'ancestors', which is much briefer than the treatment of Abraham in Stephen's speech (Ac 7:2-8) and gives quickly away to the statement that God had made them a great people during the time they lived as foreigners in the land of Egypt (again treated much fuller by Stephen in Ac 7:9-34). In Stephen's speech, Moses is the one who performs 'signs and wonders' in effecting the Israelites' release (Ac 7:36); here, in Paul's speech and in keeping with the emphasis on divine activity, it is literally God's 'uplifted arm' which leads the people out of Egypt. Israel's wilderness wanderings are also mentioned briefly in Paul's speech, 'for about forty years he endured their conduct in the wilderness' (Ac 13:18).

Paul next touches on the conquest narrative: 'and he overthrew seven nations in Canaan, giving their land to his people as their inheritance. All this took about 450 years' (Ac 13:19-20a). In Paul's speech, God is given full credit for overcoming the 'nations' of Canaan and giving the Israelites the land as an inheritance (Ac 7:3-5). Mention of specific time intervals is characteristic of Paul's speech (Ac 13:18, 20, 21) (Fitzmyer 1992:38) and also Stephen (Ac 7:6, 23, 30, 36, 42). Here, the explicit reference to '450 years' is missing from the Old Testament, but not inconsistent with Luke's rendering of this time period: 400 years of bondage in Egypt (Ac 7:6), 40 years of wilderness wanderings (Ac 7:36; 13:18) and an implied 10 years of conquest.

According to Parsons (2008:34), Paul also quickly moves over the period of the judges, but unlike the previous material of Paul's speech which was the focus of considerable attention on the part of Stephen, the portion of the speech dealing with the judges has no parallel in Stephen's speech. Paul says, 'After this, God gave them judges until the time of Samuel the prophet' (Ac 13:20b). Parsons further indicated that Samuel is also depicted as a transitional figure earlier in Acts 3:24. The shift in subject from God to the Israelites in Acts 13:21 introduces a negative element into Paul's recital of Hebrew history (1 Sm 12:1-25) (Parsons 2008:34). After removing Saul from the throne, God made David the king to his people. God testified concerning David: 'I have found David son of Jesse, a man after my own heart; he will do everything I want him to do' (Ac 13:22) (Soards 1994:24).

After the brief summary of Israel's history from the ancestors to David, the central claim of the narratio is made in Acts 13:23: 'So God has brought Jesus, one of David's descendants, to Israel to be its Savior, as he promised' (Krodel 1981:49). Paul then cites the words of John the Baptist as corroborating evidence to support his claim that God's faithfulness has climaxed in Jesus Christ. That Jesus is the fulfilment of God's promises to Israel is worked out in more detail in the second part of Paul's speech (Ac 13:26-37). Having appealed to the content of Jewish history (Ac 13:17-22) and the witness of John the Baptist, Paul now employs two favourite scriptures (Ps 2 and 16) and the rules of Jewish messianic interpretation (Juel 1988). But Christian messianic exegesis once again takes a startling turn (Ac 3:20); this Messiah whom God promised and to whom the scriptures point has already come in the person of Jesus (Ac 13:32-33). Paul before he concludes his sermon, in Acts 13:34-37, makes it clear to the people that Jesus Christ who died was raised from the dead (Krodel 1981:50):

God raised Jesus from the dead, and he will never go back to the grave and become dust. So God said:

'I will give you the holy and sure blessings that I promised to David'.

But in another place God says: 'You will not let your Holy One rot'.

David did God's will during his lifetime.

Then he died and was buried beside his ancestors, and his body did rot in the grave.

But the One God raised from the dead did not rot in the grave. (Ac 13:34-37)

The conclusion of Paul's sermon is twofold. First, Paul extends an invitation for the hearers to receive the forgiveness of sins, which can come only through our Lord Jesus Christ, not through the Law of Moses (Ac 13:38-39) (Krodel 1981: 51-52). Paul also issues a prophetic warning by quoting Habakkuk 1:5:

Look at the nations and watch - and be utterly amazed. For I am going to do something in your days that you would not believe, even if you were told. (Parsons 2008:196)

For Paul to reject his message is to reject God's salvation and to be condemned to play the part of scoffers whose fate is to be destroyed (Ac 13:41). Paul's inaugural speech is remarkably similar to Jesus' inaugural address in Luke 4 and Peter's first major speech recorded in Acts 2 (Tannehill 1990:160). All three speeches use scripture to interpret the mission (Lk 4:18-19; Ac 2:17-21; 13:47) and include Gentiles in God's salvation (Lk 4:25-28; Ac 2:39; 13:45-48).

The reactions of the people after Paul's sermon

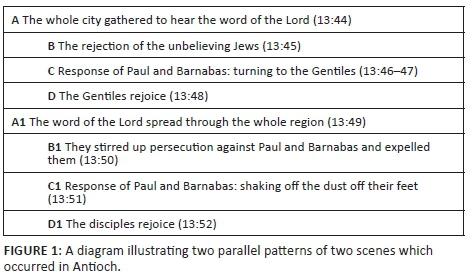

Immediately following the sermon, the people urge Paul and Barnabas to return the next Sabbath, and in the meantime the people follow these Christian missionaries who continue to exhort them (Ac 13:42-43). The rest of this unit falls into two parallel scenes (Ac 44-48; 49-52), summarising Paul's ministry in Antioch (Krodel 1981:246-247). I will differentiate the two parallel scenes by using two patterns: ABCD pattern in Figure 1 will refer to the first parallel scene and A1B1C1D1 pattern refers to the second parallel scene.

According to Parsons (2008:196), the emphasis on the Gentile mission here is underscored by the rhetorical figure of reduplication, in which one or more words are repeated for the purpose of amplification. Within a span of three verses, the word 'Gentiles' occurs three times, twice on the lips of Paul and Barnabas, and once reported by the narrator:

Then Paul and Barnabas boldly declared, 'We had to speak God's word to you first, but since you reject it and consider yourselves unworthy of eternal life, we are now going to turn to the Gentiles. For that is what the Lord ordered us to do: "I have made you a light to the Gentiles to be the means of salvation to the very ends of the earth"'.

When the Gentiles heard this, they began rejoicing and glorifying the word of the Lord. Meanwhile, all who had been destined to eternal life believed. (Ac 13:46-48a)

For Skreslet (2006:54), the repentance of the Gentile people after hearing the Word of God, was a strong vehicle that spread the Word throughout all the region of Antioch. This idea of spreading the Word of God was confirmed by Dubose (1978:52), who says, On Paul's first missionary journey, Acts records that 'the Word of the Lord spread throughout all the region' of Antioch of Pisidia (Ac 13:49). Parsons (2008:197) says:

Noteworthy also is the fact that the above pattern continues to the end of the book of Acts: (1) proclamation of the Gospel, which leads to (2) division among those listening, (3) rejection by the unbelievers, (4) withdrawal by the Christian missionaries, and finally (5) Luke's report of the progress, despite the opposition. Despite the opposition, this scene ends with the note that the disciples were filled with joy and the Holy Spirit. (Ac 13:52)

Success of the apostles' mission and division of the people in Iconium city

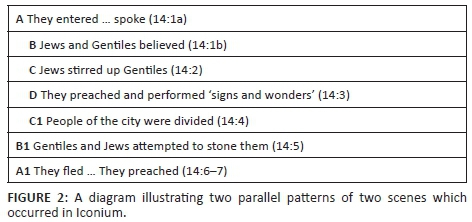

When I read Acts 14:1-7, I find that it is a tightly woven summary narrative, organised also in two parallel patterns. These parallel patterns are also confirmed by Nelson (1982:60) and Talbert (2005:123). Here, I will show how these two parallel patterns of scenes in Acts 14:1-7 are structured. In Figure 2, ABCD pattern will refer to the first parallel scene and C1B1A1 pattern refers to the second parallel scene.

Paul and his circle arrive at Iconium (Kee 1997:170-171). Immediately they entered the synagogue of the Jews as usual (14:1a) (Barrett 1994:667; Culy & Parsons 2003:271). This verse invites comparison with other scenes in which Paul and company enter the synagogues of other cities. In those instances, Paul is opposed by Jews in the synagogue. The description of the scene in Iconium, however, prevents the audience from reducing Paul's ministry to the simple formula of rejection by the Jews and success among the Gentiles (Tannehill 1990:176). Rather, Luke reports that a large number of both Jews and Gentiles believed (Ac 14:1b) (Dubose 1978:53). Furthermore, the Jews who opposed Paul turned the hearts of the Gentiles against the believers (Ac 14:2) (Schnabel 2008:85). In the midst of this strife, the apostles nonetheless stayed for a considerable amount of time and spoke boldly about the Lord who confirmed the message about his grace by causing signs and wonders to be performed through them (Ac 14:3) (Parsons 2008:197). The apostles speaking 'boldly' is another reference to what the rhetoricians call 'frankness of speech', in which:

when, taking before those to whom we owe reverence or fear, we yet exercise our right to speak out, because we seem justified in reprehending them, or persons dear to them, for some fault. (Caplan 1954:349)

Those involved in the Gentile mission perform signs and wonders, a phrase that links their mission to that of the seven (Ac 6:8; 8:6), the apostles (Ac 4:30; 5:12) and Jesus (Ac 2:22), underscoring Luke's point that the Christian movement consists of the true 'heirs' of Moses, who also performed signs and wonders (Ac 7:36).

For Parsons (2008:198), the city is split, not along ethnic lines between Jews and Gentiles but between those who hear the Word of God and accept it and those who reject the message and persecute the messenger:

But the city was divided. Some of the people agreed with the Jews, and others believed the apostles. Some who were not Jews, some Jews, and some of their rulers wanted to mistreat Paul and Barnabas and to stone them to death. (Ac 14:4-5) (Krodel 1981:54)

Thus, Paul's words in Acts 13:46-47 are not to be understood in any rigid sense; division is not always along ethnic lines, certainly not in Iconium. According to Schnabel (2008:85), when the apostles learned about their plans, 'they ran away to Lystra and Derbe, cities in Lycaonia, and to the areas around those cities. They announced the Good News there, too' (Ac 14:6-7).

Healing of the lame man and stoning of Apostle Paul in Lystra city

The scene in Lystra city (Ac 14:8-20) begins with Paul healing a man lame from birth (Ac 14:8-10), recalling the scene in Acts 3:1-10 in which Peter heals a lame man (cf. Lk 5:18-16). As such, it follows the typical form of a healing story: statement of the ailment (Ac 14:8) (Krodel 1981:54), the cure (14:9-10) and the reaction(s) (14:11-20). The description of the ailment (14:8) serves to highlight the miraculous nature of the healing. A man who could not use his feet, who had been lame since birth (A14:8) listened to Paul's preaching (Krodel 1981:54). Two elements in the description of the cure prepare the audience for the Lycaonians' identification of Paul and Barnabas as god (Strelan 2000). Firstly, Luke notes that Paul looked directly at him (Ac 14:9). That Paul's stare has, for Luke, some elements of 'paranormal vision' is demonstrated by the fact that Paul is able to 'see' that the lame man had faith to be healed (Ac 14:9). Secondly, Paul speaks in a loud voice (Ac 14:10), echoing the view in antiquity that God spoke with frightfully loud voices (a view found also in Jewish literature; Ex 19:19; 1 Sm 7:10; Ps 18:7-15; 29:3-5; 46:6; Ezk 9:1) (Strelan 2000:495-496). Given these clues, the Lycaonians' identification of Paul and Barnabas as gods would have been quite understandable to the authorial audience. That this identification is a misunderstanding, however, is clarified as the narrative unfolds.

The reactions of the Lycaonians after the healing of the lame man

According to Parsons (2008:199), reactions to the healing of the lame man vary from the Lycaonians to Paul and Barnabas to the Jews from Antioch and Iconium. As noted, when the crowd saw what Paul had done, they shouted in the Lycaonian language, 'The gods have come down to us in human form!' (Ac 14:11). Krodel (1981:55) is of the opinion that, in addition to (mis)apprehending the 'clues' of Paul's 'divine' stare and 'loud voice', the Lycaonians were especially prone to mistake Paul and Barnabas as gods because of the widely attested and well-known story that Zeus and Hermes visited this region incognito and, after being rejected by many residents of the region, were finally given hospitality by the elderly couple, Philemon and Baucis. Parsons (2008:199) argues that, 'Perhaps the hasty conclusion reached here by Lycaonians was an attempt to avoid making the same mistake twice'. That Luke's audience would have recognised this intertextual echo is seen in verse 12, in which the Lycaonians specifically identified Barnabas and Paul as Zeus and Hermes, 'Barnabas they called Zeus, and Paul they called Hermes because he was the chief speaker' (Ac 14:12) (Schnabel 2008:87). But more seems to be going on with this story (Béchard 2000, 2001). Paul is the chosen instrument to carry Christ's name to the Gentiles (Ac 9:15). Yet, only twice in Acts is Paul's missionary preaching aimed at an exclusively non-Jewish audience: here in Acts 14:15-17 (Schnabel 2008:87) and later in the Areopagus speech in Athens (Ac 17:16-34).

The contrast between these two 'Gentile' settings, however, could not be more drastic. In Athens, Paul faces a sophisticated and sceptical audience in what was still recognised as the cultural centre of the ancient world. Lycaonia, on the other hand, was regularly reckoned as one of those rural regions whose inhabitants typified the 'superstitions and uncivilised' behaviour of rustic mountain dwellers. Beyond locating the setting of this healing in a recognisably 'rustic' context, Luke provides several other hints of the remote nature of the region. He notes that the crowd speaks in the Lycaonian dialect (Ac 14:11); this is the only time that Luke refers to a local dialect. Luke also refers to a single priest of Zeus joining in the praise (Ac 14:13). The word for the 'gates' of the temple is used by Luke elsewhere in relation to a domestic structure (Lk 16:20; Ac 10:17; 12:13). This description suggests that the temple of Zeus in Lystra was hardly an imposing structure served by a 'college of priests' but was rather a rural temple-shine, which was 'an unassuming building just slightly larger than a private dwelling' served by a single priest (Béchard 2001:92).

The unbridled and uncritical reaction of the crowds in declaring Paul and Barnabas 'gods' is confirmed by the priest who is all too willing to transfer to Paul and Barnabas the accoutrements of what was evidently some festival in progress. 'The priest of Zeus, whose temple was just outside the city, brought bulls and wreaths to the temple gates because he and the crowd wanted to offer sacrifices to them' (Ac 14:13) (Krodel 1981:55). Later, their gullibility resurfaces when Jews from Antioch and Iconium convince them to join in the stoning of one whom they had only recently mistaken for a god (Ac 14:19) (Krodel 1981:55). Certainly, the unreflective response by these remote and rural mountain dwellers stands in sharp contrast to Luke's description of the agora in urban Athens, populated by sceptical representatives of the philosophical schools of the Epicureans and Stoics. One might ask the following question, 'But why present the story this way?' According to Parsons (2008:200), many critics of Christianity in the second century accused the movement of being populated by credulous and uneducated 'rustics'. Lucian, for example, charged, 'If any charlatan or trickster, able to profit by occasions, comes among them, he quickly acquires sudden wealth by imposing upon such simple folk'. Parsons further indicated that such characterisation of Christianity as a movement drawing primarily on the hoi polloi extends back even into the first century (1 Cor 1:26-31) (2008:201). In this scene, Luke defends Paul (and other Christian missionaries) 'against the charge of manipulating the uncritical naiveté of rural folk' (Béchard 2001:86). In order to do so, he employs (with variation) the literary topos of the self-disclosing sage whose commitment to wisdom and truth compels him to full disclosure in order to guard against misimpressions regarding his powers, especially among a particularly susceptible 'rustic' audience.

The apostles' response to the Lycaonians' reactions

Béchard is of the opinion that the response of Paul and Barnabas to the Lycaonians' adulations is threefold (2001:96-97): (1) they tore their clothes, (2) and rushed out to the crowd and (3) shouted:

Friends, why are you doing this? We too are only human, like you. We are bringing you good news, telling you to turn from these worthless things to the living God, who made the heavens and the earth and the sea and everything in them. In the past, he let all nations go their own way. Yet he has not left himself without testimony: He has shown kindness by giving you rain from heaven and crops in their seasons; he provides you with plenty of food and fills your hearts with joy. (14:15-17)

These actions correspond closely to the literary topos of what the sage should do who finds himself the object of a crowd's excessive admiration (Béchard 2001:97). The tearing of the garments and rushing out is obviously a symbolic gesture of 'strong disapproval' of what they were doing to the apostles. But Paul's speech makes clear that more is at stake here than Paul and Barnabas's strong disapproval of the Lycaonians' reactions as messengers 'telling you to turn from these worthless things to the living God' (Ac 14:15). Rather, Paul organises his speech along the lines of God's own self-disclosure as the 'living God, who made the heavens and the earth and the sea and everything in them' (Ac 14:15b). The emphasis on natural theology here anticipates a major theme developed in the Areopagus address (Ac 17:24-26). But, several other points seem relevant for this particular Gentile audience. Although God had allowed all the nations to go their own way (Ac 14:16; cf. Rm 1:28-31), nonetheless, he did not leave himself without a witness (Ac 14:17a). Rather, God did good things for them (Ac 14:17b); specifically he gave them rain from heaven and fruitful seasons (Ac 14:17c). There is epigraphic and iconographic evidence that older Hittite fertility gods of weather and vegetation were worshipped in local Zeus cults in Asia Minor, including Lycaonia, during the Roman imperial period (Breytenbach 1993:396-413, 1996:69-73). The effect of this part of the speech, then, is to declare to the Lycaonians that the 'living God', whom Paul and Barnabas serve, is the true 'weather' God, and not Zeus, for whom they have mistaken Barnabas. Paul and Barnabas declared that this God, not Zeus (nor Paul and Barnabas), 'has shown kindness by giving you rain from heaven and crops in their seasons; he provides you with plenty of food and fills your hearts with joy' (Ac 14:17d). So enthusiastic is the crowd, however, that even by saying these things, they barely prevented the crowd from sacrificing to them (Ac 14:18).

The stoning of Paul by the Jews from Antioch and Iconium

The story ends with one last twist on the topos of the self-disclosing sage (Parsons 2008:202). At Lystra, Paul and Barnabas do not take up stones in order to deflect excessive admiration; rather, Jews came from Antioch and Iconium, and after winning over the crowd and stoning Paul, they dragged him outside the city because they thought he was dead (Ac 14:19) (Krodel 1981:55). This inversion of the stoning motif highlights the theme of Paul's suffering for Christ's name as indicated in God's conversation with Ananias. God sent Ananias to go to the house of Judas on Straight Street to place his hands on Paul in order to restore his vision (Ac 9:11). God further said to Ananias who was afraid to go to Paul:

Go, for he is a chosen instrument of mine to carry my name before the Gentiles and kings and the children of Israel. For I will show him how much he must suffer for the sake of my name.

What God said of Paul now becomes a painful reality and is a note struck repeatedly in this chapter (Ac 14:22) (Krodel 1981:54). The vital question is, 'Is Paul ritually (and actually) stoned to death as suggested by Strelan (2004:243-253)?' The main fact is whether dead or only left for dead, efforts to destroy Paul are in vain: 'But after the disciples had gathered around him, he got up and went back into the city. The next day he and Barnabas left for Derbe' (Ac 14:20) (Schnabel 2008:88).

Paul and Barnabas's preaching the Word of God in Derbe

This last unit (Ac 14:21-28) begins with a reference to Paul and Barnabas preaching the Good News in the city of Derbe (Ac 14:21a) (Schnabel 2008:85), thus connecting to the previous story, which ends with Paul and Barnabas in Derbe (Ac 14:20). Not only do Paul and Barnabas preach the Gospel in Derbe, they are also involved in making a substantial number of disciples (Ac 14:21b) (Schnabel 2008:85). According to Parsons (2008:203), the word translated 'making … disciples' occurs elsewhere in the New Testament only in Matthew, most notably Matthew 28:19 (see also Mt 13:52; 27:57). The authorial audience, familiar with Matthew, would hear echoes of the Great Commission, in which Jesus instructs his followers to 'make disciples of all the nations'.

Strengthening in faith of the Christians in Lystra, Iconium and Antioch

After winning a large number of disciples in Derbe, the apostles then revisited Lystra, Iconium and Antioch cities with the aim of strengthening the disciples (Parsons 2008:202). Making disciples for Luke as well as Matthew involved more than evangelism and baptism (Detwiler 1995:33-41). Parsons (2008:202) argues that, 'For the Matthean Jesus, "discipling" involved "teaching them whatsoever I have commanded you"; for the Lukan Paul, it involved "strengthening the souls of the disciples"' (Ac 14:22a). To strengthen the Christians in Lystra, Iconium and Antioch, the apostles did two things, which have been discussed in the following sections.

Luke narrates Paul's clarification of the role of Christian sufferings

In order to strengthen the disciples, Paul clarifies the role of suffering as an inevitable part for God's rule and appoints leaders to continue the pastoral ministry of nurture and care for the believers (Spencer 2004:161). The critical question that one can ask is, 'What then are the implications of Paul's emphasis on suffering and succession?' Luke portraits that for Paul, suffering is a way to strengthen the disciples (Ac 14:22) (Krodel 1981:54). Exhorting the Asian Christians to remain in the faith, Paul reminds them that Christians will inevitably pass through many trials prior to entering the Kingdom of God (Ac 14:22b). For Culy and Parsons, the phrase 'through many trials' is 'fore fronted' and upsets the expected Greek word order of verb-subject-object in order to draw attention to or place emphasis upon the word or phrase being fore fronted (Culy & Parsons 2003:282). The focus on suffering is underscored also by the shift from indirect to direct discourse; 'We must go through many hardships to enter the kingdom of God' (Ac 14:22) (Schnabel 2008:85). The 'we' indicates that Paul includes himself in this suffering, a point made all the more poignant by the fact that it is addressed to believers who have only recently witnessed Paul's persecution at the hands of his opponents, culminating in his stoning in Lystra (Moessner 1990:193-194). Paul returns to these cities in which he has so recently been badly mistreated 'not in order to overwhelm his foes, but in order to attend pastorally to his communities' (Johnson 1992:256). According to Parsons (2008:203) if Luke seeks to establish continuity between the founder and followers by means of reference to miracles, he also establishes continuity between Moses and his 'true heirs' through suffering: Moses was forced into exile, having been rejected by his own as 'ruler and judge' (Ac 7:28-29); Jesus the Messiah suffers a martyr's death (Lk 23; 24:46-47; Ac 17:3); the apostles are persecuted (Ac 5:40-41); Stephen, one of the seven, is martyred (Ac 7:54-60); and Paul is stoned and left for dead (Ac 14:19-20; 9:15-16) (Krodel 1981:55). So suffering is also inevitable for the Gentile believers who hope 'to remain in faith' and 'enter the Kingdom of God'. In other words, no cross, no crown.

According to Luke, Paul appoints elders in each church to oversee Christians

Paul in addition to his clarification of Christian suffering as a way of strengthening them, he also appointed elders for them in each church (Ac 14:23) as another way of strengthening them (Krodel 1981:54). The language and convention of succession narrative found in ancient Greco-Roman, Jewish and early Christian writings is used here (Stepp & Talbert 1998:173-175). These succession stories typically used language of transfer and also comprised three components: (1) that which was being passed on is named, (2) symbolic acts accompany the transfer and (3) and confirmation that the succession has taken place (Stepp & Talbert 1998:167).

Paul also employs two of the constituent elements of a succession narrative and implicitly refers to the third: (1) that which is being transferred to the elders in Acts 14 is the pastoral care and nurture of the churches (Ac 20:28, in which this same function is labelled 'shepherding'), (2) prayer and fasting are the ritual acts accompanying the transfer (Ac 14:23b) and (3) the 'very existence of the Lukan narrative' provides implicit confirmation that elders have been faithful in strengthening the believers who face tribulations (Stepp & Talbert 1998:173).

This context of succession also sheds light on two other elements of the story. Firstly, Luke refers to 'elders' to describe those appointed to succeed Paul in the task of pastoral care. In his undisputed letters, Paul variously describes church leaders as 'overseers' (Phlp 1:1) or 'deacons' (Rm 16:1; Phlp 1:1). The Pastoral Epistles, however, do refer to 'elders' (1 Tm 5:17, 19; Tt 1:5). More important for our understanding of the term in Acts is its repeated use to describe a category of Jewish leaders (e.g. Ac 4:5, 8, 23; 6:12; 22:5; 23:14; 24:1; 25:15). Spencer is of the opinion that even in a mixed congregation in the Diaspora Luke chooses to use this term with clear Jewish connotations, thus maintaining 'certain structural associations' with non-messianic Judaism (2004:161). This point is strengthened by the fact that Luke also uses the verbal form of 'synagogue', which means 'to gather together', when he reports that Paul gathered the church together (Ac 14:27a) in Pisidian Antioch (Ac 15:30). The term 'elders' is used in Acts of Christian leaders both before (Ac 11:30) and after (Ac 20:17; 21:18) this narrative. It is used next in the tandem with 'apostles' (Ac 15:2, 6, 22). Twice in Acts 14:4, 14, Paul and Barnabas are referred to as 'apostles'. Elsewhere in Acts, this term is limited to those who had served with the 'Twelve'. Two solutions are regularly cited: (1) Luke's source uses the term and Luke does not bother to correct it (Fitzmyer 1998:526) and (2) the term in Acts 14 refers simply to Paul and Barnabas being 'sent out' (apostellō) as missionaries and has no technical sense (Barrett 1994:671-672). Like the apostles (Lk 6:13; Ac 1:2, 24), Paul is 'chosen' by Christ (Ac 9:15) and like them (Ac 10:41) was 'appointed' by God (Ac 22:14). Thus, Paul is explicitly labelled an 'apostle' here, and for the purposes of succession, Paul and Barnabas carry the apostolic authority necessary to transfer their pastoral ministry to the elders. Parsons (2008:204-205) is of the opinion that at the end of this unit, Luke narrates Paul and Barnabas continuing to retrace their steps, finally making their way back to Syrian Antioch where the episode began, thus forming a literary inclusio. In Antioch, they reported all that God had done with them (Ac 14:27b). For Krodel (1981:55) and Dowd (2002:212), Paul and Barnabas also reported that God had opened a door of faith among the Gentiles (Ac 14:27c).

Conclusion

It was clear in this article that Paul together with his company (Barnabas) positively accepted the vital work assigned to them by the church in Syrian Antioch of doing mission work to the Gentiles. The Holy Spirit who influenced the church to appoint Paul and Barnabas empowered them and gave them courage, and through the power of the Holy Spirit they stood for their faith even in times of difficulties. The Good News to the church in Syrian Antioch was the conversion of the Gentiles to be Christians. According to Rolland Allen (2006:10), 'In Acts 14:26 we are told that the apostles returned to Antioch "from whence they had been committed to the grace of God for the work which they had fulfilled"' Paul together with his companion were the instruments utilised by the Holy Spirit to reach the Gentiles with the Gospel. In conclusion, I do agree with the words of Meeks (1983:9) who says, 'Paul was a city person. The city breathes through his language'.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Allen, R., 2006, Missionary methods: St Paul's or ours? The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Barrett, C.K., 1994, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, International Critical Commentary, vol. 2, T & T Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Bavinck, J.H., 1960, An introduction to the science of mission, Presbyterian and Reformed, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Béchard, D.P., 2000, Paul outside the walls: A study of Lukes's socio-geographical universalism in Acts 14:8-20, Pontificio Instituto Biblioco, Rome. [ Links ]

Béchard, D.P., 2001, 'Paul among the Rustics: The Lystran episode (Acts 14:8-20) and Lucan apologetic', Catholic Biblical Quarterly 63, 84-101. [ Links ]

Black, C.C., 1998, 'The rhetorical form of the Hellenistic Jewish and early Christian sermon: A response to Lawrence Wills', Harvard Theological Review 81, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017816000009925 [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J., 1991, Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission, Orbis Books, New York. [ Links ]

Breytenbach, C., 1993, 'Zeus und der lebendige Gott. Anmerkungen zu Apostelgeschichte 14:11-17', New Testament Studies 39, 396-413. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500011292 [ Links ]

Breytenbach, C., 1996, Paulus and Barnabas in der Provinz Galatien: Studien zu Apostelgeschichte 13f; 16:6; 18:23 und den Adressaten des Galaterbriefes, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Caplan, H., 1954, [Cicero:] Ad C. Herennnium de ratione dicendi (Rhetorica and Herennium), Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [ Links ]

Culy, M.M. & Parsons, M.C., 2003, Acts: A handbook on the Greek text, Baylor University Press, Waco, TX. [ Links ]

Detwiler, D.F., 1995, 'Paul's approach to the Great Commission in Acts 14:21-23', Bibliotheca Sacra 152, 33-41. [ Links ]

Dowd, S., 2002, 'Ordination in acts and the pastoral epistles', Perspectives in Religious Studies 29, 205-217. [ Links ]

Dubose, F.M., 1978, How churches grow in an urban world, Broadman Press, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, A.J., 1989, Paul and his theology: A brief sketch, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, A.J., 1992, According to Paul: Studies in theology of the apostle, Paulist Press, New York. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, A.J., 1998, Luke the theologian: Aspects of his teaching, Paulist Press, New York. [ Links ]

Garrett, R.S., 1989, The demise of the devil: Magic and the demonic in Luke's writings, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Goheen, M.W., 2000, 'As the Father has sent me, I am sending you': JE Lesslie Newbigin's Missionary Ecclesiology, Boekencentrum, Zoetermeer. [ Links ]

Hedlund, R.E., 1985, The mission of the church in the world: A biblical theology, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Horrell, D.G., 2004, An introduction to the study of Paul, T &T Clark International, London. [ Links ]

Hultgren, A.J., 1985, Paul's gospel and mission, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Johnson, L.T., 1992, The Acts of the Apostles, Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN. [ Links ]

Johnson, S.E., 1987, Paul the apostle and his cities, Michael Glazier, Wilmington, DE. [ Links ]

Juel, D., 1988, The messianic exegesis: Christological interpretation of the Old Testament in early Christianity, Fortress, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Kee, H.C., 1997, To every nation under heaven: The Acts of the Apostles, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg, PA. [ Links ]

Krodel, G., 1981, Acts, Augsburg, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Meeks, W.A., 1983, The first urban Christians: The social world of the apostle Paul, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. [ Links ]

Moessner, D.P., 1990, 'The Christ must suffer, the church must suffer: Rethinking the theology of the cross in Luke-Acts', Society of Biblical Literature Seminar Papers 29, 165-195. [ Links ]

Mutavhatsindi, M.A., 2008, 'Church planting in the South African urban context, with special reference to the Reformed Church Tshiawelo', PhD dissertation, Department of Science of Religion and Missiology, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Nelson, E.S., 1982, 'Paul's first missionary journey as paradigm', Unpublished PhD thesis, Boston University. [ Links ]

Parsons, M.C., 2006, Body and character in Luke and Acts: The subversion of physiognomy in early Christianity, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Parsons, M.C., 2008, Acts, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Polhill, B.J., 1992, Acts, Broadman, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Schnabel, E.J., 2008, Paul the missionary: Realities, strategies and methods, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Shiell, W.D., 2004, Reading acts: The lector and the early Christian audience, Brill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Skreslet, S.H., 2006, Picturing Christian witness: New Testament images of disciples in mission, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Soards, M.L., 1994, The speeches in Acts: Their content, context, and concerns, Westminster John Knox, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Spencer, F.S., 1997, Acts, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Spencer, F.S., 2004, Journeying through Acts: A literary-cultural reading, Hendrickson, Peabody, MA. [ Links ]

Stepp, P.L. & Talbert, C.H., 1998, 'Succession in Mediterranean antiquity, Part 2: Luke-Acts', Society of Biblical Literature Seminar Papers 37(1), 169-179. [ Links ]

Strelan, R., 2000, 'Recognizing the Gods (Acts 14:8-10)', New Testament Studies 46, 488-503. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002868850000028X [ Links ]

Strelan, R., 2004, Strange acts. Studies in the cultural world of the Acts of the Apostles, de Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Talbert, C.H., 2005, Reading acts: A literary and theological commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, rev. edn., Smyth and Helwys, Macon, GA. [ Links ]

Tannehill, C.R., 1990, The narrative unity of Luke-Acts: A literary interpretation, vol. 2, Fortress, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Muthuphei Mutavhatsindi

albertmuta@webmail.co.za

Received: 23 May 2016

Accepted: 25 Nov. 2016

Published: 28 Feb. 2017

1 The conversion of this man results from God's instruction to Philip to go south.

2 Peter's going to Cornelius was the result of being led there by a vision and by people calling him. Peter did not know that the Holy Spirit would show him that Gentiles are welcome into the church (Ac 10).

3 Motioning of hand was the gesture to procure silence and also to invite their attention. It is also used in Acts 12:17 by Peter to the Christians who were gathered together praying at the house of Mary, the mother of John whose other name was Mark: 'But motioning to them with his hand to be silent, he described to them how the Lord had brought him out of the prison …'.