Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.36 no.3 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/VE.V36I3.1441

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The radicality of early Christian oikodome: A theology that edifies insiders ánd outsiders

Jacobus (Kobus) Kok

Department of New Testament Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In this article a study is made of the concept 'oikodome' and its derivatives in the New Testament and early Christianity. Hence, in this essay the focus is limited to the use of the term οίκοδομέω/οίκοδομή(ν) in the New Testament, and briefly turns to inspiring trajectories in early Christianity. A detailed focus on the term(s) reveals the complexity of the matter in the different Biblical contexts with its multi-layered dimensions of meaning. Subsequently, attention is turned to a study of 1 Thessalonians, followed up with a discussion of the trajectories of other-regard and radical self-giving love in the early Church as witnessed by insiders and outsiders in antiquity.

Introduction

This article was written against the background of the Faculty of Theology at the University of Pretoria's Faculty Research Theme 'Oikodome: Life in its fullness'.1

One of the challenges of a Christian faculty in the contemporary academic landscape is to what extent the research that we are doing impacts the world in which we live. In other words, is what we do relevant in any way, and could we contribute to society and academia? This essay wants to argue that the answer is yes. Christianity has something to offer, and when we turn to ancient history and wisdom, we find inspiration for the present also. This article aims to be one that could be read by theologians as well as non-theologians, and for that reason, we will attempt to limit the technical nature of the article as far as possible to make it more accessible.

During the faculty 'table discussions' held during the planning phase, the need was expressed for someone to conduct a thorough examination of the terms being used. Hence, in this essay the focus will be limited to the use of the term οίκοδομέω/οίκοδομή(ν) in the New Testament, with a brief turn to inspiring trajectories in early Christianity. A detailed focus on the term(s) reveals the complexity of the matter in the different Biblical contexts with its multi-layered dimensions of meaning. The result is that, within the space of this article, one can only scratch the top layer. Naturally, this will also lead to many questions (and problems), which will not be addressed in this article.

Next the term(s) οίκοδομέω/οίκοδομή and its derivatives will be clarified and, in the subsequent section, a study of 1 Thessalonians follows, with a discussion of the trajectories of other-regard and radical self-giving love in the early Church in contexts where the term(s) οίκοδομέω/ οικοδομή appear. The classic work(s) of Von Harnack (early Church) in dialogue with Malherbe (Thessalonians) will also be revisited.

Clarification of terms

Oikodomeo/Oikodome

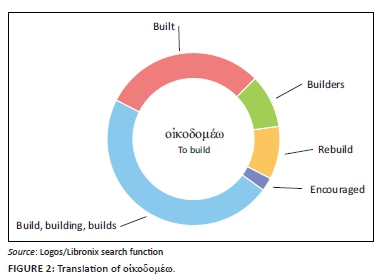

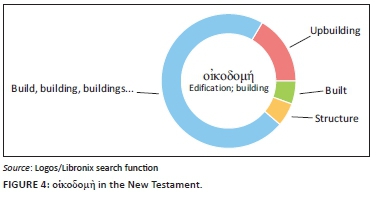

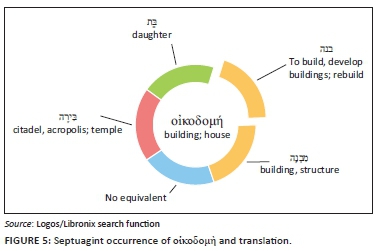

The verb οίκοδομέω occurs approximately 40 times in the New Testament (Figure 1).2In the New Testament, the translations of the word in the different contexts, comes down to (Figure 2).3 The term οικοδομή occurs 18 times4 in the New Testament (NT) (Figure 3).5 In the NT, the word is translated as follows (Figure 4). In the Septuagint, the term and its derivatives relates to the Hebrew as follows (Figure 5).

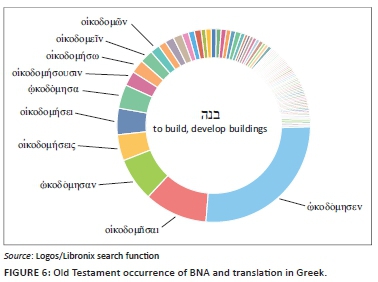

The challenge with the Old Testament (OT), however, is that the word 'to build' occurs more than 350 times in different contexts, which makes the study of the word challenging. Thus, this article is limited to the NT, which will only be done in a limited/cursory way (Figure 6).

The Old and New Testament background of οικοδομέω and its relationship6

According to Louw and Nida (1996:ad loc) - who put the words οικοδομέω, έποικοδομέω, οικοδομή and ής f: in the semantic domain 74.15 - in the NT these terms denote the following meaning: 'to increase the potential of someone or something, with focus upon the process involved ... to strengthen, to make more able, to build up'. The verbs οικοδομέω, οίκοδομεΐν' and οίκοδομή(ν) [noun] (1 Cor 14:12) denote the act of building or constructing or edifying, or the result thereof (a building/construction), whereas the noun οικοδόμος refers to the 'builder of a house' or 'architect' (Ac 4:11; cf. Lk 20:17). These terms (οίκοδομέω/οίκοδομή[ν]) are used in the New Testament in a literal7 (the act of building) and a figurative sense of the word (edifying or edification; cf. 1 Cor 14:12; 2 Cor 12:19; Rm 15:2; 1 Cor 14:3, 26). For the purposes of this article, we are especially interested in the figurative dimensions of the word and its use in the New Testament8 (Arndt, Danker & Bauer 2000).

However, let us first consider the OT and early Jewish usage of the term since the NT authors were intertextually engaged in dialogue with many of these ideas. However, this will only be dealt with in a cursory manner.

Deissmann (pp. 163ff.; quoted by Otto Michel 1964:144) and others like Elwell and Beitzel (1988) point out that ancient buildings - cities, temples, altars and the like - needed constant maintenance and restoration, and the literal meaning refers to building or restoration of the latter. Most occurrences of the term in the OT/Septuagint relates to the element of physical (up)building. In later Judaism, the life of God's people was figuratively9 related to the ideas of building or constructing and breaking or tearing down.10 In the OT, God is the subject performing the action of the verb 'to build' - God is the One who plants, gives life and builds the house of Israel, but also the One who can (or cause to) break or tear it down (cf. Jr 1:10; 24:6;11 Michel 1964:137). Hence, we often see the term used as 'a metaphor for God's activity among his people (1 Pt 2:4-8)' (Elwell & Beitzel 1988). Philo (cf. Leg. All., 2,6 & Leg. All., 3,228) also uses the term in the figurative sense of the word. 12

In the Rabbinic literature, the students of the law are described as 'builders' of the Torah (cf. Elisha b. Abuja: Ab. R. Nat., 24) - those who are participating in 'building up the world by studying and expounding the Torah' (cf. b. Ber. 64a appealing to Is 54:13; quoted by Michel 1964:137).

From a very early stage in the Christ-following movement, the concept 'building' took on a Messianic (and perhaps apocalyptic) connotation in the sense that Jesus, the Messiah commissioned by God, was presented as the One who will build the future (spiritual temple) community of faith (Michel 1964:139). Here we are reminded of Mark 14:58,13and also Matthew 16:18 where Jesus says to Peter: καί έτπί ταύτη τη πέτρα οικοδομήσω μου τήν έκκλησίαν καί πύλαι αδου ού κατισχύσουσιν αυτής (Mt 16:18).14 Clearly, the futurum (οικοδομήσω) indicates that the action will take place in the future, and that Jesus is the subject of the verb and the έκκλησίαν is the object of the verb. In Acts 15:16, the promise is made that 'μετα ταΰτα αναστρέψω καί ανοικοδομήσω τήν σκηνήν Δαυίδ τήν τπετπτωκυΐαν καί τα κατεσκαμμένα αύτής ανοικοδομήσω καί ανορθώσω αύτήν'.15 Here in Acts, the author develops and builds on an OT idea (cf. άνοικοδομεϊν). This text is a 'free quotation'16 of Amos 9:11 (cf. also Jr 12:15) in which the eschatological spiritual restoration of Israel and the restoration of fellowship with God is denoted (cf. Michel 1964:163). God will destroy sinners, but will not destroy the house of Jacob (see Am 9:1-10). Kistemaker & Hendriksen ([1953] 2001) states that here:

At the time of the Jerusalem Council, James indicates that this messianic prophecy of Amos has been fulfilled with the entrance of Gentiles into the church. James teaches that Israel, restored through Jesus Christ, extends a welcome to the rest of mankind in spiritual fellowship. (p. 554)

This carries with it a vision of restoration and reconciliation that belongs to the heart of the Christ-following movement.

Pauline development of the concept οικοδομή

The community of faith as God's building (οικοδομή)

Hence, it is not strange to see the above-mentioned ideas used in a figurative sense by early Christians like Paul, for example (cf. especially 1 Cor 14:3-5;17 2 Cor 5:118). Paul made use of the images of architecture (to explain the relation between σωμα, ναός and οικοδομή; cf. Trossen p. 804 quoted in Michel 1964:144). The term οικοδομή in the New Testament can be used to refer to physical buildings, like the temple (Mk 13:1; Mt 24:1), and even figuratively to refer to man's corporeality (cf. body as tent in 2 Cor 5:119). Paul also uses the term οικοδομή in a figurative sense to refer to the community of faith, for instance in 1 Corinthians 3:9, where he states that the believers are 'God's building' - under permanent construction (θεοΰ γάρ έσμεν συνεργοί, θεοΰ γεώργιον, θεοΰ οικοδομή20 έστε;21 Michel 1964:145).

In the Pauline tradition, as we see in Ephesians 2:21-22, the faith community as οίκοδομή is the holy temple of God that is built on the foundation of the apostles and the prophets, and of which Jesus is the cornerstone (Eph 2:21-22 - έν φ πάσα οικοδομή συναρμολογουμένη αΰξει είς ναόνάγιον έν κυρίω, 22 έν φ καί ύμεΐς συνοικοδομεΐσθε είς κατοικητήριον τοΰ θεοΰ έν πνεύματι;22 Michel 1964:14523). The term έποικοδομέω is also used to denote the act of building further upon something (Michel 1964:147). This term is found in the NT inter alia in the context of 1 Corinthians 3:1-23, where Paul speaks about his role and that of Apollos. Like architects, the apostles lay the foundation (1 Cor 3:10 - ώς σοφός αρχιτέκτων θεμέλιον εθηκα, άλλος δέ έποικοδομεΐ ... θεμέλιον τιθέναι) and others (should) build on that foundation (1 Cor 3:12-14 - εί δέ τις έποικοδομεΐ έπίτόν θεμέλιον) - and consequently believers are being built up in the process (1 Cor 3:10 - έποικοδομηθέντες; Michel 1964:147). This idea is also taken further in the Pauline tradition using the term συνοικοδομέω (Eph 2:22) in which the unity between Christ, the apostles and believers are accentuated (Michel 1964:14724).

Believers as agents of edification

Related to the idea of the community of faith as an οίκοδομή, we see the development of the idea of οίκοδομή as an act of spiritual edification or upbuilding. Paul sees his own apostolic authority as having the purpose of building others up, instead of breaking people down (2 Cor 10:8 - εδωκεν ό κύριος; 2 Cor 13:10 - ό κύριος εδωκέν μοι είς οίκοδομήν καί ούκ είς καθαίρεσιν;25 cf. Michel 1964:140).

For Paul, οίκοδομεΐν' is an apostolic activity and a spiritual task of the community of faith. Paul, in effect, adopts and modifies the OT concept of the idea. Paul accentuates the fact that the actions of believers should contribute to the spiritual upbuilding and edification of the community of faith (1 Cor 14:12,26 2627; Rm 15:228 & Eph 4:29). In the well-known discussion of the value of the different spiritual gifts, Paul uses this term to argue that only that which builds up the community of faith has any value (1 Cor 14:3). In the same vain, Paul argues in Romans 14:19 that one should not do anything that could cause one's brother to stumble, but rather do that which leads to mutual edification, i.e. actions that build one's fellow believer up (Rm 14:19 - 'Άρα ούν τα τής είρήνης διώκωμεν και τα τής οίκοδομής τής είς αλλήλους;29 cf. also 1 Th 5:11). Paul uses this term in 1 Corinthians 14:3 in relation to παράκλησιν (encouragement) and παραμυθίαν (consolation), which deals with the upbuilding or edification of the believers, aimed at the growth and development as well as the unity of the faith community. We also find this notion in the Pauline tradition, in which the same idea is continued and slightly adapted, namely that the faith community is a body that is to be built up in love, as we see in Ephesians 4:16 (τήν αΰξησιν του σώματος ποιείται είς οίκοδομήν έαυτου έν αγάπη;30 Michel 1964:145).

Stewardship (οικονόμος) used in a metaphorical way

Logically flowing from the above we find, especially in Paul and the later tradition, the notion of stewardship in which the term οίκονόμος is used in a metaphorical way. In 1 Corinthians 4:1, Paul uses the word in association with servant and says that apostles are entrusted with the secrets or mysteries of God (Οΰτως ήμας λογιζέσθω άνθρωπος ώς ύπηρέτας Χριστου και οίκονόμους μυστηρίων θεου) to which they should be faithful (Michel 1964).

In the Pauline tradition, as in Titus 1:7, the author states that a bishop must both be above reproach (άνέγκλητον: μή αυθάδη, μή όργίλον, μή πάροινον, μή πλήκτην, μή αίσχροκερδή) and like a steward (ώς θεου οίκονόμον) of God (Michel 1964). Similarly we see in 1 Peter 4:10-11 that believers (and especially those in church office) should serve (διακονουντες) as good stewards (ώς καλοι οίκονόμοι), the abundant grace of God. Michel (1964) refers to later tradition - especially Ignatius (Pol., 6, 1), who goes even further and makes this case applicable to the community as a whole: 'Labour together, fight, run, suffer, sleep, watch with one another31 as God's stewards, companions, and servants' (ώς θεου οίκονόμοι και πάρεδροι και ύπηρέται).

To summarise

The term οίκοδομέω as verb denotes the act of building or edifying, and as noun (οίκοδομή) it denotes physical buildings, like the temple, or figurative buildings, like the community of faith as God's οίκοδομή. In the later tradition of Paul and Peter, for instance, we see that office bearers should be like stewards serving the community and building forth on and protecting the mysteries that have been received from the apostles. In the NT, the action of 'upbuilding' or edification seems to be directed towards those on the inside, i.e. it seems to have a sentripetal focus towards the insiders.

However, what about the rest of the world? Do we find any evidence that this 'upbuilding' also has a focus towards outsiders? The answer is yes! The early Christ-followers had a radical focus towards those on the inside and also towards the upbuilding and restoration of those outside the community of faith.

Let us consider one passage in which the term οίκοδομή occurs and in which we see the focus towards outsiders as well - starting with one of Paul's earliest letters, if not the earliest letter, namely Thessalonians.

Paul and the Thessalonians

Background of 1 Thessalonians

During Paul's second missionary journey, around 48-51 AD after having visited Neapolis and having planted a church in Philippi where he baptised Lydia, he visited Thessalonica (cf. Ac 17:1) where he stayed a few months. Thereafter he left for Athens and sent Timothy, who had been in Macedonia at the time, to visit the Thessalonians (Malherbe 2014:188). By early 50 AD Paul was in Corinth. Soon after, Timothy met up with him and brought him news about the Thessalonians. Subsequently, Paul wrote the letter to the Thessalonians (see Malherbe 2000:71-74).

Paul's letter to the Thessalonians is a particularly special letter in many ways. Most scholars agree that this letter is most probably one of Paul's earliest letters, which means that it is at present the oldest surviving document of early Christianity that we possess (Powell 2009:371). This in itself makes this letter very interesting. In this letter we see the earliest missionary content to people who have recently come to conversion. For that reason, the letter reflects characteristics of a young church - for instance, the clear intent to strengthen the faith of recent converts and an effort to provide them with moral guidance (Malherbe 2014:188).

Thessalonica was a bustling Macedonian metropolis and port city with approximately 100 000 inhabitants (Powell 2009:373). Archaeological finds revealed that this city, as was typical of busy seaports during the time, seems to have been home to several pagan shrines and temples of which we can name a few: Isis, Osiris, Serapis, Cabirus, etc. (Powell 2009:373). Paul seems to have made a living working in Thessalonica. He was not like some pagan philosopher who sponged on the believers. He states that he worked night and day, and in the process also made use of the opportunity to proclaim the gospel to those he came in contact with (1 Th 2:9). Powell (2009:373) correctly observes that ancient Roman cities like Thessalonica had many insulae or market buildings, which contained living spaces on the top level and on the bottom floor had a shop that was visible from the street. It is possible that Paul, Timothy and Silas might have stayed in one of these insuluae and that they occupied themselves with leatherwork and tentmaking (cf. Ac 18:3). This might have created the ideal opportunity for sharing the gospel and, from Paul's perspective in the letter, seems to have been even more successful than his engagement with Jews in the synagogue. The church in Thessalonica seems to have been born out of these 'market encounters' with non-Jews (Powell 2009:373).

Abraham Malherbe illustrated that there is a significant parallel between Paul's teachings and that of pagan moral philosophers, as he so elegantly illustrated in his classical commentary on Thessalonians (Malherbe 2000) and elsewhere (Malherbe 2014).

After the historical narrative section of the letter (chapters 1-3), Paul lays a philophronetic foundation in chapters 4-5 in which he gives the community of believers practical moral advice (Malherbe 2014:188). In the historical narrative section, Paul builds rapport with the readers by means of contemporary ancient conventional forms, which reminds of the epistolographic feature of 'letters of friendship' (Malherbe 2014:189). Paul writes about Timothy's message that the believers 'have a good memory of him' (cf. 1 Th 3:6) and that they still look to him for moral guidance (Malherbe 2000:206-208, 2014:189). The image of the teacher is like a dialogical voice within the believer or the convert. This reminds us of the 'moral hortary tradition', according to Malherbe (2014:189), of which we find a good example in Lucian. Here Nigrus, a recent convert, is saying (Nigr. 6-7 [LCL, transl. A.M. Harmon]; quotation from Malherbe 2014):

Then, too, I take pleasure in calling his words to mind frequently, and have already made it a regular exercise: even if nobody happens to be at hand, I repeat them to myself two or three times just the same. I am in the same case with lovers. In the absence of the objects of their fancy they think over their actions and their words, and by dallying with these beguile their lovesickness into the belief that they have their sweethearts near; in fact, sometimes they even imagine that they are chatting with them and are pleased with what they formerly heard as if they were just being said, and by applying their minds to the memory of the past give themselves no time to be annoyed by the present. So I too, in the absence of my mistress Philosophy, get no little comfort out of gathering the words that I then heard and turning them over to myself. In short, I fix my gaze on that man as if he were a lighthouse and I were adrift at sea in the dead of night, fancying him by me whenever I do anything and always hearing him repeat his former words. Sometimes, especially when I put pressure on my soul, his face appears to me and the sound of his voice abides in my ears. Truly, as the comedian says, 'He left a sting implanted in his hearers'. (p. 189)

Not only is the the image of the teacher like a dialogical voice within the believer or the convert, but the teacher becomes a model for the converts to follow (who edifies). For that reason, the believers are motivated to imitate Paul, like children would imitate their father (1 Th 1:5-7; cf. 1 Cor 4:16-17). Thus, Paul 'remains their paradigm in his absence' (Malherbe 2014:190).

The reality of life in its unfullness

In the opening verses of the letter it immediately becomes clear that the radical spiritual transformation that the believers experienced when they turned from the idols to serve the living and true God, was not simply a turn towards 'life in fullness'. This have turned them into people who are loved by God and who have been called by God (ήγαπημένοι ύπό [τοΰ] θεοΰ, τήν έκλογήν ύμων), which becomes particularly clear (cf. οτι [conjunction, adverbial, causal]) in the fact that the Gospel came (έγενήθη [Aor Ind Pas]) to them not in the form of mere human words, but with power in the Holy Spirit and in much assurance (1 Th 1:5 - ούκ έγενήθη είς ύμας έν λόγω μόνον άλλα καί έν δυνάμει καί έν πνεύματι άγίφ καί [έν] πληροφορία πολλη,). However, it is particularly interesting that Paul mentions the fact that this spiritual transformation of the believers immediately brought them in a situation in which they had to face at least some form of opposition and distress. Next, it becomes interesting how Paul addresses this reality. Let us consider this matter in more detail by looking closely at 1 Thessalonians 1:6-10 (Table 1).

In this text, the reality of the experience of affliction is surrounded by several theological affirmations. In the first instance, Paul affirms the truth that the believers are beloved by God (ήγαπημένοι), and that they have been chosen (τήν έκλογήν ύμων) by God (1 Th 1:4), as mentioned above. He also focuses their attention on the concept of imitation.32In the process of accepting the word of God and becoming God's beloved and elected, they were in effect sharing the suffering of their Lord and imitating him (1 Th 1:6). In Paul's thought, and in the early Christian understanding as such, this was a particularly important point. This way of thinking forms the basis of the early Christian identity and ethics since it is part of the framework in which the fundamental unity of identity and ethos comes together - that point of departure is the believer's unity with Christ expressed in the reality of a new (transformed) being.

Schnelle (2009:320) points out that: 'The point of departure for Paul's understanding of ethics is the new being, since incorporation into the death and resurrection of Jesus . determines the present and the future'. Jesus becomes the Urbild [prototype] and Vorbild [model] (Schnelle 2009:321). Just as Christ served, suffered and died, so Christ-followers, who are new creations (2 Cor 5:17), should be prepared to face the same fate and participate in imitatio Christi. Christ's actions were motivated by self-giving love (cf. 2 Cor 5:14; Rm 8:35, 37), and in the same manner, the Christ-followers are to serve in love (Gl 2:6). The life and death of Christ, and the love with which he served and died, is presented as the pattern for the believer. Schnelle (2009) correctly points out that:

What began in baptism continues in the lives of those baptized: they have been placed on the way of Jesus, they imitate Christ, so that the apostle even say: 'Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ' (1 Cor. 11:1; cf. 1 Thess. 1:6; 1 Cor. 4:16). The Christian life is founded on Jesus's way to the cross, which is at the same time the essential criterion of this life. The ethical proprium christianum is thus Christ himself, so that for Paul, ethics means the active dimension of participation in Christ. (p. 321)

Hence, in the background of Paul's words to the Thessalonians, we find a deep theological conviction. By the grace of God, and in the context of their affliction, they have managed to become an example to all believers in Macedonia and all over (cf. 1 Th 1:4-10). Paul wants to comfort them with the knowledge that this form of persecution that they experience, and the suffering that it entails, was analogous to the suffering the Jewish Christ-followers experienced at the hands of other Jews. In fact, in their suffering, they were participating in the suffering of Jesus. Thus, the earliest Christian document does in no way paint a picture of life in grandiose fullness or material success. Rather, from the beginning it paints the picture of the inevitable - that a life that follows Christ will have to face the reality of suffering. The fullness and the blessing, it seems ironically, is to be found in the midst of the suffering, in the spaces between the cracks and the edges of the shadows. For believers are children of light, amidst the darkness and brokenness of this world. This is where the challenge lies - to show love in a context of affliction and suffering, and in that way participate fully in their identity that follows the way of Jesus.

This brings us to 1 Thessalonians 5:12ff., where Paul gives the believers his final exhortations and greetings.33 In the previous section (1 Th 4:13-18), Paul comforted the believers by reminding them of the Lord's coming, which should provide them both with an expectation of deliverance (1 Th 1:10) and hope34 (see Ridderbos 1971:595, 622). This is contrasted with the false hope of peace and security (1 Th 5:2; Ridderbos 1971:545) that the Roman Empire promises. Those who put their trust in the things of this world are sons of darkness (1 Th 5:4-5). Believers are sons of light who should be sober (1 Th 5:6-8). Their destiny is not to be overcome by God's wrath, but to be saved by God's salvation (1 Th 5:9). Believers are to live according to their identity, that is, to live in such a manner that it could be said that whatever they do, they live and act in Christ (1 Th 5:10). Therefore (cf. Διό -logical inferential conjunction), or as a result thereof, the believers should encourage one another (παρακαλείτε άλλήλους) and also build each other up (οίκοδομείτε είς τόν ενα; cf. also Gl 6:1ff.).

In the final exhortation section (1 Th 5:12ff.), Paul beseeches the believers to do the following:

- respect those who labour among them, and those who are over them in the Lord, and those who admonish them

- esteem them very highly in love, because of their work

- they should be at peace amongst themselves

- they should admonish the idlers

- encourage the faint-hearted

- help the weak

- be patient with all

- they should not repay evil with or for evil

- always seek to do the good towards each other and also towards all people

- they should rejoice, always

- pray constantly

- give thanks in all circumstances

- do not quench the Spirit

- do not despise prophesy

- they should test everything

- hold fast to what is good

- abstain from evil.

At first glance, Paul's admonitions sound just like that of any other moral philosopher. However, one should not read these texts too lightly. For the early Christians, radical love for each other and even for those outside of the community of faith, as well as doing good, was the hallmark of Christian identity (cf. 1 Th 3:12; 4:6; Rm 2:10; Gl 6:10; Schnelle 2009:334). Early Christians believed that in following Christ's pattern of humility, they should regard other people as more important than themselves and put their needs above that of their own (cf. 1 Th 4:6; 1 Cor 10:24; 33-11:1; 13:5; 2 Cor 5:15; Rm 15:2ff; Phlp 2:5-11). Schnelle (2009) remarks:

Christian love, as the determining power in the life of the church, is essentially unlimited (1 Cor. 13) and applies to everyone. It knows no egotistic selfishness, no quarrelling, and no divisive party spirit, for love builds up the church (1 Cor 8:1). This love changes the social structures of the church because believers have all things in common (Gal 6:6) and because they help those in need (cf. Gal. 4:10ff) and practice hospitality (Rom. 12:13). (p. 334)

This sounds like an old cliché and nothing new. But perhaps the early Christians were more radical in this regard than we tend to think. Although these ethical demands sound like any other contemporary 'common' moral advice of the day, there is of course a very big difference in the motivational basis of the ethics.35 Where the philosopher turned to himself (cf. Epictetus, Diatr. 3.23.16 - έπιστρέφειν έφ' αύτόν), the Christians accentuated the fact that a person turns to God (cf. 1 Th 1:9-10 - έπεστρέψατε πρός τόν θεόν από των είδώλων). In fact, both the Jewish and Christian apologists accentuated the idea that all of their actions have God as its starting point. We clearly see this notion in the Epistle of Aristeas (Let. Aris. 200-201) and also with the Christian apologist, Athenagoras (Supplicatio pro Christianis, 11-12), who claimed that the Christian doctrines derive from God (cf. also Aristides, Apologia 15; Theophilus, Atol. 3.15; referred to by Malherbe 2014:198).

In the first instance, God in and through Christ is the model and deepest motivation for their identity and ethical behaviour. Early Christians like Paul believed that there was a significant difference between the motivation for action when it comes to them and other groups. To this end, Christian identity was motivated by a belief that God had created them into a new being (2 Cor 5:17 - ώστε εϊ τις έν Χριστώ, καινή κτίσις; cf. Gl 6:15). They also believed that their ethos was a result of the work of God within them. That is an important difference. Secondly, we also see that the early Christians made use of kinship language to describe the nature of their relationships - a matter that drew the attention of outsiders as well. One example could be mentioned: the pagan, Caecilius, in his attack on the Christians, reacted to the early Christians' kinship language and their love for one another, and perhaps also implicitly on the egalitarian structure within the Christian community(s) (Minucius Felix, Oct. 9.2 [ACW, transl. G.W. Clarke], quoted by Malherbe 2014):

They recognize each other by secret marks and signs; hardly have they met when they love each other, throughout the world uniting in the practice of a veritable religion of lusts. Indiscriminately they call each other brother and sister, thus turning even ordinary fornication into incest by the intervention of these hallowed names. Such a pride does this foolish, deranged superstition take in its wickedness. (p. 194)

The early Christian apologist, Minucius Felix, in his defence of the Christ-followers, said the following (Oct. 31.18; cf. Tertullian, Apol. 39, quoted by Malherbe 2014):

It is true that we do love one another - a fact that you deplore -since we do not know how to hate. Hence it is true that we do call one another brother - a fact which rouses your spleen - because we are men of the one and same God the Father, co-partners in faith, coheirs in hope. (p. 194)

The early Christians had a very special bond between them and used kinship language, which was noticeable by the pagans. This special understanding of their fraternal relationship to each other was rather unique in the ancient world, and for that reason also the basis of the critique against them.

One of the most interesting questions is what exactly attracted people to the Christian faith, if their moral advice was rather similar to that of the Umwelt? In which way was the answer offered by Christianity 'better' than that of the moral philosophers or the Jews? In the history of interpretation, scholars answered this question in different ways. Nock (1964:1, 67, 1933:215-216, 218, 220; see Malherbe 2014:189-199; cf. also Ameling 2011:246-248) for one, who wrote in a time in which the parallel between Christianity and pagan moral philosophy was accentuated, argued that it was Christianity's proximity to the latter that made it attractive and created fertile ground in the process. However, Malherbe (2014:201) accentuates that there was a major difference to be noted as well. For instance, both Paul and his contemporary Musonius Rufus (cf. Fragment 12 & 13) would argue that extra-marital sex was wrong (cf. πάθος έπιθυμίας in Paul; 1 Th 4:7). However, the basic motivation for saying this fundamentally differed from one another. The uniqueness of Paul's message (e.g. in 1 Th 4:5, etc.) was that it had a theological basis as motivation - i.e. it relates to holiness and sanctification - whereas Musonius Rufus would argue that a person who is guilty of sexual sin acts in an irrational way. Thus, Paul has a clear theological motivation for admonishing the believers for not conducting lustful sexual behaviour. For Paul, this kind of behaviour is inconsistent with the nature of a Christian being a newly created being in Christ and who should live a life 'worthy of the one that called them' (Malherbe 2014:20136). Clearly this is a whole other ball game.

Others, like Adolf Von Harnack (1904), take a different approach to the question on why the early Christians were so successful in attracting people to the movement. This particularly concerns us, since it deals with the radical way that Christians illustrated love towards insiders and outsiders. In the earliest Christian document we possess, we see how Paul prays that the believers might increase in love for one another and also in love for all (1 Th 3:12; cf. Gl 6:10). This is presented as being a moral obligation to which every Christian is called. In 1 Thessalonians 4:9, Paul says that the believers were taught by God (θεοδίδακτοί) how to love one another and that they should continue to do so. Malherbe (2014:203) points out that the concept φιλαδελφία was used by the pagans mostly to refer to love towards blood relatives. Paul uses it differently - he extends that to those who are part of the household of faith, that is, beyond the social boundaries of blood relations. The love for the brother that Paul is speaking about does not refer to the 'inborn capacity' of friendship like we have with the Stoics, nor the utilitarian motivation like with the Epicureans, but because love towards one's brother (as general virtue in antiquity) is made into 'a divine mandate' or 'religious command' given by God (Malherbe 2014:203-204). Even more radical than this was the notion that the love command is to be extended not only to fellow believers, but even further in a social-transcending way to include outsiders who are not part of the community of faith. This was a radical different approach in antiquity that went beyond social and ethical conventions. Paul wants the believers to increase and abound in love, even towards outsiders (cf. 1 Th 3:12). Hence, Christians are not called to retaliate or retract from society, but to (radically) transformatively engage with society and do the good towards all people (1 Th 5:15). In 1 Thessalonians 5:12, Paul says that Christ-followers should act becomingly (ευσχημόνως) towards outsiders (τους εξω) and in the process win their respect (cf. ίνα περιπατήτε ευσχημόνως πρός τους εξω).

The radicality of early Christian sensitivity towards outsiders

Let us fast forward to the early Church period and turn our attention to the radicality of the way early Christians went about to show love towards each other and towards outsiders, and how they transcended social boundaries. Harnack (1904:181-249) argues that the early Christian movement's uniqueness and radicality related to the way in which it was a movement of love and charity. Harnack (1904) refers to Tertullian (in Apolog., xxxix):

It is our care for the helpless, our practice of loving-kindness, that brands us in the eyes of many of our opponents. 'Only look' they say, 'look how they love one another!' (they themselves being given to mutual hatred). 'Look how they are prepared to die for one another!' (they themselves being readier to kill each other).' Thus had this saying been fulfilled: 'Hereby shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another'. (p. 184)

For Harnack (1904:184-185) it was clear that the gospel was a 'social message' of 'solidarity' and 'brotherliness', which 'raises the social connection of human beings from the sphere of convention to that of moral obligation'.

In the emerging institutional Church, for instance in Justin (Apology [c. Ixvii] and Tertullian [Apolog., xxxix]) we see that, and also how the early Christians looked after the widows and orphans, the sick and disabled, prisoners, poor people who needed a burial, and slaves. We also see how they cared for others (even outsiders) in times of great calamities, as well as how they showed hospitality to fellow brethren who were on a journey.

According to Tertullian, at least once a month, believers brought gifts (money or the like) to the church, which was then entrusted to the president who, in collaboration with the deacons who knew the context in which believers lived, distributed the gifts to the needy (Harnack 1904:13). In Eusebius' H.E., vi. 43 we read that the Roman Church at that time supported 1500 widows and poor people (Harnack 1904:197). In the liturgy, widows and orphans occupied a special place, a tradition that we already see in the New Testament (cf. Ja 1:27; cf. also Hermas, Mand., viii. 10). Similarly, the early Church supported the sick, the disabled and the poor. Not only were they always prayed for (cf. 1 Clem Iix. 4), but the Christians also visited the sick and the poor. In Tertullian (ad uxor., ii. 4) we read of the interesting scenario of a woman who was married to a pagan man, who did not particularly like the fact that his wife had to go into the streets and visit other men, especially those who were sick, and that she stayed in poor and backward areas. It was the task of the deacons (and deaconesses) to ascertain who was in distress and to make sure that those persons were not excluded from the funding that the church provided (Harnack 1904:199). For that reason, one of the main characteristics of those in office was that they should have the trait of φιλόπτωχος, that is, lover of the poor. Some Christians went so far as to lend money from pagans in an effort to relieve the distress of the poor (Tertullian, de idolat., xxiii).

Another dimension of care was the visitation of prisoners, where Christians not only visited but also refreshed, encouraged and edified those who were in prison (cf. already Heb 10:34). Some of the well-known examples are from Eusebius (cf. Apost. Constit., v. 1) where we read of the 'Palestinian martyrs during the Diocletion persecution' who were encouraged and edified by other believers (Harnack 1904:203, fn. 3). According to Eusebius (in Hist.Eccl., v., 8), the amount of care that Christians showed towards prisoners caused the Emperor Licinius to pass a law that demanded that 'no one was to show kindness to sufferers in prison by supplying them with food, and that no one was to show mercy to those who were starving in prison' (Harnack 1904:204). In fact, Licinius apparently attached a penalty to those who showed compassion, to the extent that they would also be incarcerated if they disobeyed the order. According to Eusebius, this law was directed against the Christians, for they were the ones that went the extra mile in showing compassion to those in jail.

In the ancient world it often happened that some poor people could not get a proper burial. According to Aristides (Apol., xv), it so happened that whenever poor Christians died, a fellow Christian would see that such a person gets a proper burial. The believers cared for each other in rather radical ways and in the process protected the honour of fellow members, even after death (Harnack 1904:206). It even happened that some Christians not only limited their good acts to fellow believers, but extended it to outsiders. One of the most striking examples of this is found in Lactantius (Instit., vi. 12) who states (quoted by Harnack 1904):

We cannot bear ... that the image and workmanship of God should be exposed to wild beasts and birds, but we restore it to the earth from which it was taken, and do this office of relatives even to the body of a person whom we do not know, since in their room humanity must step in. (p. 206)

Last but not least, the early Christians' care for people who got sick during times of great calamities should be pointed out. Against the background of the 2014 outbreak of the Ebola virus in West Africa, the picture of the early Christians caring for sick and infected persons illustrates the absolute radicality of early Christian sensitivity and love for others (see Harnack 1904:212-215). Harnack (1904:212-213) points to the plague that raged in Alexandria during circa 259 AD. During that time Dionysius (cf. Eusebius, Hist. Eccl., vii. 22, quoted by Harnack 1904) recalls:

The most of our brethren did not spare themselves, so great was their brotherly affection. They held fast to each other, visited the sick without fear, ministered to them assiduously, and served them for the sake of Christ. Right gladly did they perish with them. Indeed many did die, after caring for the sick and giving health to others, transplanting the death of others, as it were, into themselves. In this way the noblest of our brethren died, including some presbyters and deacons and people of the highest reputation... Quite the reverse was it with the heathen. They abandoned those who began to sicken, fled from their dearest friends, threw out the sick when half-dead into the streets, and let the dead lie unburied. (pp. 212-213)

We find very similar stories elsewhere, for instance in Cyprian (cf. de Mortalitate) in reference to the plaque that raged in Cartage (cf. per Pont., ix), which cannot be discussed in this essay due to limited space. Suffice to say, we do find in Cyprian that the early Christians not only relieved the need of insiders, but also of outsiders. Cyprian's biographer Pontanius (cf. Vita, ix. f.) stated that Cyprian motivated believers to do good towards all, even towards enemies, which in fact resulted in an overflow of good works in practice (Harnack 1904:214).

One final example that could be put forward is the 'self-denying' and self-emptying love that believers showed, even towards outsiders, during the plaque that broke out during the reign of Maximinus Daza, of which we also read in Eusebius (cf. Hist. Eccles., ix. 8). Adolf Von Harnack translates this section in Eusebius as follows (Eusebius, Hist. Eccles., ix. 8; translated by Harnack 1904):

For the Christians were the only people who amid such terrible ills showed their fellow-feeling and humanity by their actions. Day by day some would busy themselves with attending to the dead and burying them (for there were numbers to whom no one else paid any heed); others gathered in one spot all who were afflicted by hunger throughout the whole city, and gave bread to them all. When this became known, people glorified the Christian's God, and convinced by the very facts confessed the Christians alone were truly pious and religious. (pp. 214-215)

Conclusion

Against the background of what we have just seen, it is clear that the admonitions Paul gave to the Thessalonians, namely that they should grow and abound in doing good towards each other and to edify both insiders and outsiders, were not just empty words. The early Christian message was a radical one that took people on radical trajectories. In the earliest Christian letter we possess, the values of self-sacrificial love and other-regard in the context of suffering and affliction based on the example of Christ and apostles like Paul can already be seen. By the early fourth century, this obscure movement on the margins of the Roman Empire would have grown to such an extent that it would eventually become the official religion of the Roman Empire. This movement certainly impacted the world in many positive ways. Today the question facing us all is to which extent will we continue the Great Narrative of the Missio Dei and participate in God's mission of restoration and reconciliation?

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Ameling, W., 2011, 'Parànese und Ethik in den kleinasiatischen Beichtinschriften', in R.J. Deines & K.W. Niebuhr (eds.), Neues Testament und hellenistisch-jüdische Altagskultur, pp. 241-249, Mohr Siebeck, Tubingen. (WUNT 274). [ Links ]

Arndt, W., Danker, F.W. & Bauer, W., 2000, A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature, 3rd edn., pp. 696-697, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Barr, J., 1961, The semantics of Biblical language, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Elwell, W.A. & Beitzel, B.J., 1988, Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Gibson, A., 2001, Biblical semantic logic, 2nd edn., Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Green, G.L., 2002, The letters to the Thessalonians, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Harnack, A., 1904, The mission and expansion of Christianity in the first three centuries, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York. [ Links ]

Kistemaker, S.J. & Hendriksen, W., [1953] 2001, Exposition of the acts of the apostles, Baker Book House, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Kittel, G., Bromiley G.W. & Friedrich, G. (eds.), 1964, Theological dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 5, pp. 136-148, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Louw, J.P. & Nida, E.A., 1996, Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament: Based on semantic domains, 2nd edn. (electronic edn.), pp. 675-678, United Bible Societies, New York. [ Links ]

Malherbe, A.J., 1989, Paul and the popular philosophers, Fortress, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Malherbe, A.J., 2000, The letters to the Thessalonians, Doubleday, New York. (AB 32B). [ Links ]

Malherbe, A.J., 2014, 'Ethics in context: The Thessalonians and their neigbors', in J. Kok, T. Nicklas, D.T. Roth & C.M. Hays (eds.), Sensitivity towards outsiders, pp. 187-208, Mohr Siebeck, Tubingen. (WUNT 2/346). [ Links ]

Michel, O., 1964, 'Oikodomeo', in G. Kittel, G.W. Bromiley & G. Friedrich (eds.), Theological dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 5, pp. 136-148, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Niebuhr, K.W., 1987, Gesetz und Paranese: Katechismusartige Weisheitsreihen der jüdischen Literatur, Mohr Siebeck, Tubingen. (WUNT 2.28). [ Links ]

Niebuhr, K.W., 2011, 'Jüdisches, jesuanisches und paganes Ethos im frühen Christentum', in R. Deines et al. (eds.), Neues Testament und hellenistisch-jüdische Altagskultur, pp. 251-274, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Nock, A.D., 1933, Conversion: The old and the new in religion from Alexander the great to Augustine of Hippo, Clarendon, Oxford. [ Links ]

Nock, A.D., 1964, Early Gentile Christianity and its Hellenistic background, Harper & Row, New York. [ Links ]

Porter, S.E., 1996, 'Linguistic issues in New Testament lexicography', in S.E. Porter (ed.), Studies in the Greek New Testament: Theory and practice, pp. 49-74, Peter Lang, New York. [ Links ]

Powell, A., 2009, Introducing the New Testament, Baker, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Ridderbos, 1971, Paulus: Ontwerp van zijn Theologie, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Schnelle, U., 2009, Theology of the New Testament, Baker books, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Swanson, J., 1997, Dictionary of Biblical languages with semantic domains: Greek (New Testament), Logos Research Systems, Oak Harbor. [ Links ]

Thompson, J.W., 2011, Moral formation according to Paul, Baker academic, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Witherington, B., 2011, 'Raising the Barr: The legacy of James Barr', viewed 09 June 2015, from http://www.patheos.com/blogs/bibleandculture/2011/10/22/raising-the-barr-the-legacy-of-james-barr/ [ Links ]

Yonge, C.D., 1995, The works of Philo: Complete and unabridged, Hendrickson, Peabody, MA. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kobus Kok

246 St Jansbergsesteenweg, Heverlee, Leuven 3001, Belgium

kobus.kok@up.ac.za

Received: 27 Feb. 2015

Accepted: 04 Aug. 2015

Published: 30 Nov. 2015

This article represents a theological reflection on the Faculty Research Theme (FRT) of the Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, entitled 'Ecodomy -Life in its fullness'. The theme is portrayed from the perspective of various theological disciplines. A conference on this theme was held on 27-28 October 2014.

1 This article is an adapted form of the article read at this conference.

2 Table generated by means of Logos Bible Software.

3 Table/figure/pie chart electronically generated by means of Logos Bible Software.

4 See Matthew 24:1 (temple building); Mark 13:3 (buildings); Romans 15:2; 1 Corinthians 3:9; 1 Corinthians 14:12 (edification); 2 Corinthians 5:1 (house not made with hands); 2 Corinthians 10:8 (building you up); 2 Corinthians 13:10 (building you up); Ephesians 4 (equipping and building up).

5 Table/figure/pie chart electronically generated by means of Logos Bible Software.

6 This part of the article strongly depends on and builds forth on the work of the Tubingen scholar, Otto Michel (1964), in Kittel's Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, as well as that of Arndt et al. (2000). Naturally, as all New Testament scholars are aware - especially those of the University of Pretoria where Jannie Louw (cf. Louw & Nida 1996) was a prominent scholar - the work of Kittel, Bromiley and Friedrich (eds. 1964) dates from a time before the prominence of James Barr's (1961) approach in the Semantics of Biblical Language. For that reason, we are also critical in our use of Kittel et al. and take the development since Barr into consideration against the background of developments in linguistics. See Gibson (2001:3) for the way in which Barr's work entailed a 'reconstruction of descriptive Biblical linguistics'. Barr made us aware of the flaws in etymology-based word studies and also that it is not wise to simply assume word equivalents in different Semitic languages. It is also not so easy to compare Greek and Semitic thought or to simply contrast it. In Barr's aforementioned book there is a whole chapter on Kittel and its problems. Words get their meaning in sentences and in contexts, and more than often the meaning(s) are more than the sum of the individual lexical parts (cf. strawberry = straw + berry of which the sum is more than the lexical parts). The reader of the article unfamiliar with the debate should also consult the article of Witherington (2011) in this regard and also that of other prominent New Testament and Ancient Greek scholars, like Porter (1996). See also Swanson (1997) for semantic studies.

7 See Luke 6:48; Matthew 21:33; Mark 12:1; Luke 14:28; Mark 14:58; 16:3 (Isaiah 49:17); Luke 12:18; Matthew 23:29; Luke 11:47; Genesis 8:20; Exodus 1:11; Ezekiel 16:24; Luke 7:5; Acts 7:47, 49; 16:2; Matthew 7:24; Luke 4:29; 6:49.

8 According to Michel (1964:144), the concept 'οίκοδομεΐν' has a teleological, spiritual, cultic and ethical dimension.

9 For another example of figurative 'upbuilding' in the OT, see Proverbs 14:1 ('A wise woman builds her house'). See also perhaps Jeremiah 29:6; 42; 10, etc.

10 Michel (1964:139) points to: '1 Ch. 26:27: του μή καθυστερήσαι τήν οίκοδομήν του οϊκου, 1 Esr. 2:26: ήργει ή οίκοδομή του ίερου, 4:51: είς τήν οίκοδομήν του ίεροΰ δοθήναι'; See also 1 Chron 26:27 (rebuild the house of God - ά ελαβεν έκ πόλεων και έκ των λαφύρων, και ήγίασεν άπ' αυτών του μή καθυστερήσαι τήν οίκοδομήν του οϊκου του θεου)'.

11 Jeremiah 24:6 (NIV): 'My eyes will watch over them for their good, and I will bring them back to this land. I will build them up and not tear them down; I will plant them and not uproot them'.

12 Here in Legum Allegoriae (Leg. All., 3, 228), according to Michel (1964:138), Philo allegorises Numbers 21:27ff., according to which Philo argues that if we trust only on our own calculations and 'erect and build the city of the spirit which destroys truth'. In De Cherubim 101-103ff. we also see Philo using the metaphor of building: Yonge (1995:90-91) translates Philo as follows: 'If therefore we call the invisible soul the terrestrial habitation of the invisible God, we shall be speaking justly and according to reason; but that the house may be firm and beautiful, let a good disposition and knowledge be laid as its foundations, and on these foundations let the virtues be built up in union with good actions, and let the ornaments of the front be the due comprehension of the encyclical branches of elementary instruction; (102) for from goodness of disposition arise skill, perseverance, memory; and from knowledge arise learning and attention, as the roots of a tree which is about to bring forth eatable fruit, and without which it is impossible to bring the intellect to perfection.' (103) But by the virtues, and by actions in accordance with them, a firm and strong foundation for a lasting building is secured

13 Mark 14:58 - οτι ήμεΐς ήκούσαμεν αυτου λέγοντος οτι έγώ καταλύσω τον ναόν τουτον τον χειροποίητον και δια τριών ήμερών άλλον άχειροποίητον οίκοδομήσω. Translation (NIV): 'I will destroy this man-made temple and in three days will build another, not made by man'.

14 Translation of Matthew 16:18 (NIV): 'And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it'.

15 Translation of Acts 15:16 (NIV): 'After this I will return and rebuild David's fallen tent. Its ruins I will rebuild, and I will restore it, that the remnant of men may seek the Lord, and all the Gentiles who bear my name, says the Lord, who does (footnote 15 continues...) these things' that have been known for ages'. In Amos, God promises that after Jerusalem has been destroyed, he will cause his people to rebuild and restore it (Kistemaker & Hendriksen ([1953] 2001:553). The reference to the house of David and to people from different nations (Jews and Gentiles) that will come to it, is eschatological in nature (Is 2:2-4; 55:3-5; Zch 14:16).

16 The quotation in Acts 15:16 of Amos 9:11-12 differs in some places from both the Septuagint and the Hebrew texts (see Kistemaker & Hendriksen [1953] 2001:553). Hence, it is perhaps one of the most challenging citations in the NT when it comes to determining the vorlage. It differs from the Septuagint, apart from the fact that there are several Septuagint versions, which makes the debate about the possible vorlage even more difficult. Also note the remark by Kistemaker and Hendriksen ([1953] 2001:553): 'A Dead Sea Scroll (4QFlor 1.12) of Amos 9:11-12 features this text in Hebrew in wording that corresponds with the quotation in Acts'. The tent of David refers to the temple.

17 See 1 Corinthians 14:3-5, where it is used in the sense of edification or upbuilding of believers. In these verses, we read (1 Cor 14:3-5 NIV): 'But everyone who prophesies speaks to men for their strengthening [οίκοδομήν], encouragement and comfort. He who speaks in a tongue edifies himself [εαυτόν οίκοδομεΐ], but he who prophesies edifies the church [έκκλησίαν οίκοδομεΐ]. I would like every one of you to speak in tongues, but I would rather have you prophesy. He who prophesies is greater than one who speaks in tongues, unless he interprets, so that the church may be edified' [ϊνα ή έκκλησία οίκοδομήν λάβη].

18 For the occurrence of the word οίκοδομή referring to a finished building, see Mark 13:1 and Matthew 24:1 where it is used to refer to the temple.

19 Michel (1964:146) points out that in Paul, the term οίκοδομή is also used as a figure of speech referring to man's corporeality: 'According to 2 C. 5:1 the earthly body is a tent (οίκία τοΰ σκήνους) which can be dismantled (έαν ... καταλυθη ...). But then we have a house from God (οίκοδομή έκ θεοΰ) which is not made with hands (αχειροποίητος), which is eternal, and which is ready in heaven (αίώνοις έν τοΐς ούρανοΐς). The very wording of this eschatological passage is most striking. Perhaps we are to think of Mk. 11:58: καταλύειν, οίκοδομεΐν, αχειροποίητος.'

20 οίκοδομή is here in the nominative , feminine singular.

21 Translation of 1 Cor 3:9 (NIV): 'For we are God's fellow workers; you are God's field, God's building.'

22 Translation of Eph 2:21-22 (NIV): '21 In him the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you too are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit.'

23 Cf. the later tradition in Ign. Eph., 9,1. And also Past. Herm. Visiones 3, 2, 6. (Quoted in Michel 1964:146).

24 Information from: Kittel et al. (eds. 1964).

25 Translation of 2 Cor 13:10 (NIV): [7]he authority the Lord gave me for building you up, not for tearing you down'.

26 1 Cor 14:12 (NIV): 'So it is with you. Since you are eager to have spiritual gifts, try to excel in gifts that build up the church.'

27 1 Cor 14:26 (NIV): 'What then shall we say, brothers? When you come together, everyone has a hymn, or a word of instruction, a revelation, a tongue or an interpretation. All of these must be done for the strengthening of the church.'

28 Rom 15:1-2 (NIV): 'We who are strong ought to bear with the failings of the weak and not to please ourselves. Each of us should please his neighbor for his good, to build him up.'

29 Translation (NIV): 'Let us therefore make every effort to do what leads to peace and to mutual edification.'

30 Translation (NIV): 'From him the whole body, joined and held together by every supporting ligament, grows and builds itself up in love, as each part does its work'.

31 See Kirsop and Lake's translation (Loeb Classical Library [LCL]: pp. 275; quoted in Michel 1964:ad loc): 'rise up together as God's stewards' (cf. sunegeiresthe).

32 Green (2002:97-98) correctly opines that it was commonplace in the ancient world that the ideal student is someone who imitates his master, a model for moral instruction and education. These models ranged from parents, well-known heroes and also esteemed teachers. Green (2002:97-98) further notes: 'Xenophon, for example, described the role of the teacher, saying, "Now the professors of other subjects try to make their pupils copy their teachers." In Jewish literature the imitation of model lives was a commonplace in moral instruction, whether one imitated the conduct of a person (Wis. 4:2; T. Ben. 3:1; 4:1), a person's sufferings (4 Macc. 13:9), or the character of God himself (T Asher 4:3; Ep. Arist. 188, 210, 280-81). In the NT we find repeated exhortations to imitate the leaders of the church (1 Cor. 4:16; 11:1; Gal. 4:12; Phil. 3:17; 4:9; 2 Thess. 3:7, 9; 1 Tim. 4:12; Titus 2:7; 1 Pet. 5:3), other members of the community of faith (Phil. 3:17; Heb. 6:12; 11; 13:7), and "what is good" (3 John 11), as well as God and Jesus Christ (Eph. 5:1; 1 Cor. 11:1). In the patristic literature, the fathers of the OT (1 Clem. 9-12, 17-18), Christian leaders (1 Clem. 19), and Christ himself (Pol. Phil. 8) are all put forward as examples to follow'.

33 In this section, Paul admonishes the believers to respect those who are their leaders and to accept their critical guidance. Today, in our contemporary society, admonition and critique within the church context is an anathema, but as Green (2002:250) correctly points out, in ancient times it was commonplace for people to submit to their leaders and expect their critique as part of their own growth and upbuilding (cf. Philo, Eph. 6:4; Philo, De Specialibus Legibus 2:232; Wis. 11:10).

34 Ridderbos (1971:545) remarks: 'Daarom kan de komst des Heren niet alleen een motief tot heiliging, maar ook een bron en grond van troost zijn in de teenwoordige "verdrukking", een woord, dat ook niet slechts op incidentele tegenslag of moeite ziet, maar zeer bepaald de aan die komst van Christus voorafgaande, laaste fase van de tegenwoordige wereld karaktiriseertt ['For that reason the coming of the Lord not only serves as a motive of holiness, but also as a source of comfort in the present "tribulation", a word, that does not only refer to the present adversity, but is also linked to the future coming of Christ and the time precipitating his coming, which is to be seen as characteristic of the final phase of the present world'].

35 For the parallel between Paul and the popular philosophers, see Malherbe (1989, 2000). Malherbe (2014:196) argues that the moral teaching of early Christians, and even that of Hellenistic Judaism, did not differ significantly from that of the pagan moral philosophers. Some examples are found in the early Christian writings itself: for instance, the fact that Paul's contemporary, the Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus was well-known and respected by people like Clement of Alexandria. Another example is the respect for Seneca, as we see from Tertullian's work. For (Hellenistic) Jewish traditions, see Thompson (2011), Niebuhr (1987:70-72, 2011) and also Ameling (2011) as referred to by Malherbe (2014).

36 This is also evident in 1 Peter 1:14-16, for instance. Christians should be holy, as God is holy and for that reason there is no room for unholy sexual passions.