Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.36 no.2 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/VE.V36I2.1435

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Vhuthu in the muta: A practical theologian's autoethnographic journey

Wilhelm van Deventer

Department of Practical Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

A practical theologian constructs his autoethnographic and interactive narrative with Venda people and others. His own journey is integrated with those of church and community members. These joint lived experiences were shared in the households and families of the relevant co-participants. The concept of Vhuthu in the muta is explored in relation to its potential and problematics by means of autoethnographic stories, relevant literature, art, poems and linguistics. The article appreciatively and critically reflects upon Vhuthu and its possible value for practical theology.

Introduction

My family and I arrived in the now defunct homeland of Venda on 30 November 1982. After we had spent a few days settling in, Mr Butinana Ramovha, a church elder and Vhamusanda [traditional headman] visited us and handed me an old book on the Venda language (Ziervogel, Wentzel & Makuya 1961). Thanking him, I asked him whether there might be one specific Tshivenda word which is of particular significance. He turned to page 32 (Ziervogel et al. 1961), pointed to Vhuthu and said: 'You'll experience it every day because here in Venda, we do things together.'

Not only did I experience Vhuthu and many of its facets, but I studied it in depth with the intention of trying to understand the mindset and lifestyle of the people I served in order to be of more value to them. The longer I became involved in ministerial work, the deeper the relationships and interaction between the congregants, the community and myself grew. It was through these adults, young people, children, artists, poets and writers of the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa, Congregation of Tshilidzini, and the surrounding communities that I could learn the rural Venda way of feeling, thinking, speaking and doing. This all developed over 16 years of involvement in congregational and community activities such as church services, Sunday school, youth gatherings, women's conferences, birthdays, weddings, funerals, festivals, protest meetings and marches and, especially, through home visits.

The latter was done at least four to five times at the homes of 706 families. My responsibilities also implied that I had to sleep over in numerous homes over many weekends and, from time to time, during the week.

Formally, I engaged in autoethnographic interviews, focus groups, participant observation, joint reflections with co-participants and peer reviews with many of the people mentioned above, as well as with traditional leaders, traditional healers and academics. Apart from my own research, I also regard the experiences of my wife's involvement in hospital, community and family medical care over the same period of time and our children's seven years of attendance at a local Venda school as complementary to that of my own processes of learning.

However, in spite of these privileged lived experiences, my insights remained limited, and I therefore continued to research Vhuthu and related concepts such as Ubuntu and Botho through my involvement in informal settlements, farming communities and townships in the North-West Province. This autoethnographic journey took me, and still takes me, on roads regularly travelled and others less travelled. It takes me through moments of knowing and lack of insight, answers and increased questions and mostly times of acute awareness of the complexities, discrepancies, evasiveness, intangibility, paradoxes and the seen and unseen of the concept of Vhuthu. A young Venda doctor, Rudzani Muloiwa (1999:30), confirms these difficulties by writing that it is almost impossible to translate the word Vhuthu into English.

Ellis, Adams and Bochner (2011:1) as well as Holt (2003:18-28) and Pace (2012:1-15) explain autoethnography as a process and product emanating from personal narratives within the context of intercultural involvement and reflection. Long-term lived encounters, conversations, artifacts, personal and collaborative interpretation, self-critical review and relevant literature integration are all part of autoethnography. Due to its subjective character, autoethnography is evocative in nature as it challenges conventional approaches to research. It does not pretend to be generally representative or commonly applicable, but it focuses on research integrity and trustworthiness.

Given the numerous meanings attached to and applications of ethnography (Ellis et al. 2011:6), for instance in the contexts of physical ethnology, cultural anthropology, ethno-cultural approaches, social anthropology, social-cultural anthropology, cultural and intercultural psychology and ethno-musicology, my own autoethnographic journey finds its grounding in what Miller-McLemore (2012a) refers to as 'practical theology as a way of life' when he writes:

... practical theology refers to an activity of believers seeking to sustain a life of reflective faith in the everyday, a method or way of understanding or analyzing theology in practice used by religious leaders and by teachers and students across the theological curriculum, a curricular area in theological education focused on ministerial practice and subspecialties, and, finally, an academic discipline pursued by a smaller subset of scholars to support and sustain these first three enterprises. Each understanding points to different spatial locations, from daily life to library and fieldwork to classroom, congregation, and community, and, finally, to academic guild and global context. The four understandings are connected and interdependent, not mutually exclusive. (p. 16)

The point of departure in this article is therefore the concrete embodiment of practical theology in the local context and represents my personal journey in search of a life of reflection on the 'everyday' of Vhuthu in the muta [courtyard, family, family of grasses]. I shall attend to the praxis in the muta as the primary context of a particular way of life. I shall try to understand it by means of an interpretation of narratives of lived experiences, relevant literature, art, poems and other linguistic aspects and risk concluding remarks for a hopefully deeper insight into the concept of Vhuthu [being human in relation to, with and through other humans and other beings].

Positioning myself in Vhuthu

To involve oneself in the field of autoethnographic research, interpretation and formulation is by no means an easy task. On the one hand, one is intensely aware of the difficulties pertaining to the concept of Vhuthu and one's own limited experience in the muta. On the other hand, one remains sensitive towards the presuppositions which are brought about by one's own predominantly Christian, modern and postmodern Western life and world views in relationship and in comparison to the rural thought patterns, symbols and values of the Venda people.

To this, one has to add the fact that one is not merely dealing with two separate systems of identity and culture but that, within each of these lives and worlds, a large number of variables are present. Furthermore, each of these lives and worlds entail a very dynamic creative tension and reciprocal interaction between the two and their variable views of the life and the worlds mentioned above. And of course, more people, lives, worlds and interactive processes are present than the two mentioned, which further complicates and enriches mutual acculturation (Hanekom 1979:1-12).

Evolutionary changes therefore constantly take place within and between identities and cultures. This process of acculturation did however not merely occur within and between the two life and world views present in me and the Venda people, but the very same dynamics of ever-changing thought patterns, symbols and values, creative tension, reciprocal interaction, disintegration, re-integration and enrichment also takes place in the whole of one's own self.

Ultimately, we should never lose sight of the fact that all of us as people are human beings, belonging to one common humanity. The perspectives pertaining to Vhuthu which will be discussed in the following paragraphs are therefore reflections on my own experiences within the muta. Admittedly this involvement, participation, experience and reflection were and still are provisional, even tentative, and the conclusions drawn are therefore subjective and by no means to be understood as generally representative and/or commonly applicable, though founded in research integrity and trustworthiness. Overlaps and distinctions between Vhuthu, Ubuntu, Botho and other similar and differing concepts will of necessity be present, but in this article, the emphasis is on Vhuthu.

Predominantly Vhuthu

Although one can identify many inherent differences, there was, over many decades, and still is sufficient consensus about the fact that the core of the concepts of Ubuntu and Botho and the Tshivenda concept of Vhuthu can be described as an integrated whole which binds together all corresponding and even apparently contradictory aspects of universal life into an open and ever-expanding spiral of unity, harmony, equilibrium and continuity. Sources in this regard include Bosch (1974), Du Toit (2005), Farisani (1988), Kudadjie and Osei (1998), Manganyi (1973), Mashige (1996), Mbiti (1969), Setiloane (1986; 2000), Soyinka (1976) and Vilakazi (1998). Van Wijk (1984) quotes Watson when writing the following:

... it is a deep sense of unity with people and with nature. 'There is in African custom an essential harmony and equilibrium with the land ... All of life is seen as a continuum of interrelated beings with person taking a special place. Life itself as life-power is present throughout the continuum and can be transmitted back and forth. (p. 186)

People's being is thus determined by this concept of totality by means of which all internal and external dimensions of their existence (spirituality, religion, economy, judicial systems, politics, kinship, language, education, play, art, science, et cetera) are fused into purpose relationships (Myburgh 1981).

These relationships hold between the divine, persons and nature (the divine and person, the divine and nature, person and the divine, person and persons, person and nature, nature and the divine, nature and persons, nature and nature). This is Vhuthu and constitutes the entirety and fullness of being human.

In his poem 'Vhuthu', Ratshitanga (Van Deventer 1991:42, transl. O. Rambau) describes the above-mentioned entanglement of Vhuthu dimensions as follows:

Like water breaking mountains apart

Forming crevices through hills

Till the river reaches the sea

Unity was like that even before

Like the tongue assisting the teeth

While the intestines do the final digestion

Through unity we can move mountains

And promote development

Unity is our priority

Together we preserve it

Just like ornaments

We protect our country

Like spiced gravy

Delicious to the cook himself

Forward we go

With unity our spear

Unity and love are related

They cater for each other

Together they create peace

Within which we stay in harmony

Unity is education!

Unity at work!

Unity on the roads!

If we unite, success is ours

In this poem, Vhuthu is described directly and by means of metaphors and similes in terms of unity, strength, history, co-operation, preservation, protection, promotion, development, progress, readiness, education, work, infrastructure, transport, love, peace, harmony and success. A person is therefore a person through other persons, but, in view of the poem above as well as in other proverbs and idioms emanating from our continent, the Vhavenda are people through the following:

- the divine: we are dressed in the clothes of the spirit of the deceased

- his/her land: the land never reveals the secrets of its heart and it is time to invoke the ancestors to provide life and wealth as we sow

- crops and cattle: a young man's pride is his cattle

- house and home: a woman's life, joys and sorrows are the house, but an elderly lady's home is the road

- labour: to work makes a person

- health: my doctor and my ancestral spirits keep me well

- knowledge and wisdom: knowledge-knowledge is people.

These sayings reveal that the concept of Vhuthu (also Ubuntu and Botho) is not confined to the communal relationships between people alone as, for instance, stated by Shutte (2001:2) and Broodryk (2002:13). It entails 'more', namely divine, spiritual, creational, concrete and bodily dimensions (Du Toit 2005:853; Kelsey 2009:556; Meiring 2014:292; Setiloane 1998:75; personal conversation with Prof. Fhumulani Mulaudzi, Head of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, University of Pretoria and an expert in Indigenous Knowledge Systems [IKS], 19 January 2015).

In fact, linguistically, the concept Vhuthu is not a noun. It is derived from muthu [human being, person] and vhathu [human beings, people]. Vhuthu is therefore a descriptive and qualitative abstract and cannot be defined and/or translated in terms of delineated words such as 'humanity' and 'humanness'. Vhuthu, as is the case with Ubuntu and Botho, can only be constructed by means of autoethnographic and narrative experiences and interpretations of and reflections on personal involvement, listening to stories, observations, writings, art, et cetera in the muta.

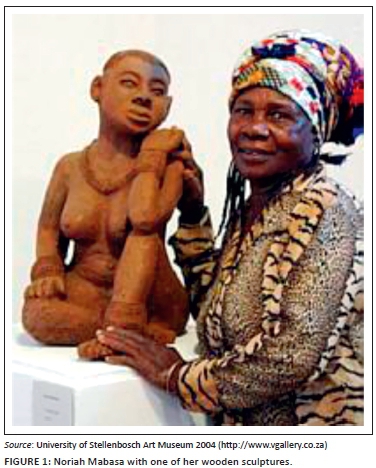

A case in point is the Venda artist, Noria Mabasa, who is best known for her large wooden sculptures. She was a member of our church, and I had the opportunity to spend many an hour with her. Much of her art centred on themes of people in fields, forests and rivers.

Noria, whose homestead is an open-air art exhibition in itself, explained to me that she found her initial inspiration to practise art in a recurring dream in which an elderly lady taught her how to proceed. She also told me that she found the right wood to work with by talking to the trees. Her ideas, she said, came from the 'mouths' of the various pieces of wood and through her dreams in which the ancestral gods and spirits instructed her what to carve.

It is necessary to state here that the presence of the divine and ancestral gods and spirits is by no means experienced by the rural Venda people as supernatural and/or magical. It is a given and a normal way of life for the ancestors to permeate daily existence in all its facets and features. They are, therefore, together with dreams, fields, forests, rivers and people, an integral part of Vhuthu.

However, Vhuthu is not to be generalised in the first place, as is mostly the case with Ubuntu and Botho. In fact, Ubuntu is primarily applicable in clan context whilst Vhuthu finds its meaning predominantly in the household and family.

Muta and Vhuthu: Where things come together

The Venda word muta means courtyard, family and family of grasses (Van Warmelo 1989:240). The integrated whole of the human, concrete and natural dimensions of the concept muta are therefore reflected within the word itself. Not only does the word have these three simultaneous meanings, but it is also in the circle of the courtyard of rural Venda homes where the family, neighbours and others primarily exist and frequently meet for social gatherings, weddings, funerals, et cetera.

In the majority of cases, these courtyards take a circular shape, and the round huts, connecting walls and floors are built from mud, clay and cow dung whilst the roofs are made of poles, grass and locally obtained iron stone. Some of the sides are decorated with drawings which consist of traditional patterns and symbols reflecting animals, reptiles and flowers.

Most of the courtyards have a small circle in the middle which is used as a fire place, serving the purpose of providing light and heat, whilst communal cooking is done here. Domestic animals such as dogs, cats, chickens and goats also make themselves at home in the muta.

Although transitional, modern and combinational architectural structures are increasingly erected by the Venda people, the muta as courtyard and family still remains the primary concept and context within which everything comes together for the majority of Venda people' (personal conversation with Prof Mashudu Mashige, Department of Applied Languages, Faculty of Humanities, Tshwane University of Technology, 20 January 2015).

The muta is furthermore an open system with merely a gap in one of the small walls as entrance and exit. These connecting walls are so low that one's horizontal perspective includes the whole panorama of people, land, crops, cattle, trees, mountains, houses, buildings, roads and vehicles, and one's vertical perspective includes the sky, sun, moon, stars, clouds, thunder and lightning.

However, the above-mentioned communalistic-cosmological existence does not only take place in the muta as a physical location. The muta is also a spatial condition and even extends beyond the grave, and as such, family relationships are just as important in death as they are in life.

Death is, in the context of the rural Venda concept of cyclical time, believed to be the source of life itself. When the deceased re-joins the ancestral gods and spirits, the life cycle is set forth via conception, the unborn, birth, the living, et cetera.

A poem illustrates this (Van Deventer 1988:11, my translation):

Generations

In the courtyard there are three

A pregnant widow

Thus far, the concept of Vhuthu was presented as primarily descriptive in nature, and its positive expression was explained. It might seem like an outline of idealism, but Vhuthu is by no means perfect and without flaw.

Muta and Vhuthu: Where things fall apart

The disintegration of a person's relationships can lead to the disintegration of the self, and these relationships within themselves also affect Vhuthu. The result of all this is that people are no longer a unity within themselves whilst the continuity of their relationships towards the divine, people and nature are simultaneously distorted. This means that the muta as family and courtyard can also be the context within which 'things fall apart' (Achebe 1958) because, although the holistic communalism and cosmology definitely represents the basic and therefore most influential and positive value in the Vhuthu of the Venda population, it is precisely the dynamics of this value which constitutes serious problems due to external and internal disturbances.

Van Wijk (1984) describes both the positive value and the problematics as follows:

The profound sense of unity and equilibrium has often been described as one of the outstanding characteristics of African culture ... To endanger the equilibrium is to endanger life and survival itself.

To endanger the equilibrium is to endanger life and survival itself means that if one aspect of the whole is disturbed, then, of necessity the whole of life would be disturbed. (p. 186)

In order to explain the destructive colonial effect on the integrated whole of African life, '. Mphahlele quotes from Jordan's translation of the mock eulogy which Mqhawi delivered to a no doubt unsuspecting Prince of Wales during the latter's visit in 1925' (Van Niekerk 1982:28-29):

Ah, Britain! Great Britain!

Great Britain of the endless sunshine

She hath conquered the oceans and laid them low;

She hath drained the little rivers and lapped them dry;

She hath swept the little nations and wiped them away;

And now she is making for the open skies

She sent us the preacher; she sent us the bottle;

She sent us the Bible, and barrels of brandy;

She sent us the breechloader, she sent us cannon;

Oh roaring Britain! Which must we embrace?

You sent us the truth, denied us the truth;

You sent us the life, deprived us of life;

You sent us the light, we sit in the dark,

Shivering, benighted in the bright noonday sun

In the same manner, apartheid also had its dehumanising and divisive effect in church and society.

The original Tshilidzini church building with its unique traditional architectural design was constructed in such a way that it made provision for the separation of white people, Venda Christians (who were not allowed to wear traditional attire) and the unconverted amongst the Venda people. During the unrest in 1976 in South Africa, this building was burnt to the ground in protest against the separation of the family of God in the church.

The mere fact of the establishment of the so-called 'independent and self-governing state of Venda' during 1979 was a result of the grand narrative of the Nationalist Party's policy of 'separate development'. Many families' lives were destroyed by moving Shangaans out of Venda to Gazankhulu and vice versa.

Mphephu became president of the 'Republic of Venda', and no opposition was tolerated. Detractors were arrested and detained without trial for up to 90 days. In 1981, a member of our church died in detention. Due to their pastoral support to the mourning family and their involvement in the deceased's funeral, black clerics were incarcerated, and my white predecessor was unceremoniously deported out of Venda back to South Africa.

After PW Botha missed the Rubicon in August 1985 and instituted the national state of emergency called 'Operation Iron Fist' in June 1986, I was involved in assisting parents to search for their lost children, some who were illegally detained at unknown venues and others who fled into exile. Unfortunately, I also had to break the bad news to many people about the death of their loved ones, and I buried their loved ones who, for instance, died at the hands of covert security operations in bordering countries, at Boiphatong and in the Germiston bombing.

Today, two 1984 paintings by the Venda artist Avhashoni Mainganyi still hang in our passage.

The first is of two cattle horns which embrace land, hills, huts and a rising sun. The sun, however, does not rise from behind the horizon but comes up out of the African soil itself.

In the second, a man stands in the forefront, holding his arms aloft. A broken fence separates him from his wife whilst a ploughed field, hills and a community of huts stretch out in the background. The man's anger is portrayed by him greeting his wife, the ploughed field, hills, huts and community by swinging a working tool as he leaves for work far away.

These paintings explain our African idealism, which is uncritically emphasised by many Ubuntu proponents, but together with the other examples above, they also depict the realistic association between the external disturbance of one aspect of the whole (for instance, colonialism, apartheid, separating people in church, homeland divisions, deaths in detention, incarceration without charge, deportation, suffering and, as the paintings reflect, migrant labour) and the simultaneous disturbance of the whole. If we bear in mind that Neluvhalani (1987:185) reveals that a lack of love and mercy undermines the communalistic and cosmological whole of Vhuthu, it is inevitable that the disintegration of the whole also affects the related Vhuthu virtues negatively, and this in turn disrupts the whole. The vicious circle continues, and a person's whole life and world falls apart until this corruptive process becomes his or her style of existence.

Vhuthu can, however, also be disrupted from within the muta. It is therefore not only external factors such as colonialism, apartheid systems, structures, laws and practices and migrant labour which cause disintegration within the family.

Mbiti (1969) refers as follows to the essentially communalistic African view of a person:

... only in terms of other people does the individual become conscious of his/her own being, his/her own duties, his/her privileges and responsibilities towards himself/herself and other people. Whatever happens to the individual happens to the whole group, and what happens to the whole group happens to the individual. The individual can only say: 'I am because we are; and since we are therefore I am.' (pp. 108-109)

Manganyi (1973:30) expresses a similar view when he says that black people have a 'communalistic' orientation towards life and a 'corporate personality'.

Amongst the Venda people, these communalistic relationships find their practical application mainly in the context of the muta and by means of the informal and formal research processes mentioned in paragraph 1. It is apparent that these dynamics are controlled internally by means of primarily six stabilising Vhuthu systems, namely status (royalty over the general public), gender (men over women), age (older people over the youth), kinship (for example, an older sister (makhadzi) over her brother's children), reciprocity (attending others' funerals so that mine can be attended too) and the divine (the ever-present powers of the ancestral gods and spirits). Traditionally, this system of controlling mechanisms was supposed to ensure order and peace within the group and community and was executed by means of hierarchical authority.

However, in recent times, such authority has been finding itself in a predicament, for instance, through the above-mentioned external pressures, the misuse of the authority mechanisms (for example, the dictatorial domination of some chiefs, government officials and men) and the disintegration of these mechanisms (for instance, the development of a vacuum as far as the father-figure is concerned). For the family structure, this creates severe problems relating to reciprocal commitment and loyalty as well as feelings of inferiority amongst husbands and the psychological and physical abuse and neglect of wives and children. At the same time, modern and postmodern patterns such as urbanisation, 'foreign' economic systems, judicial procedures, advanced medical science, electronic and social media, the emancipation of women, a lack of discipline amongst young people and migrant schooling lead to increased vulnerability in the muta.

Control systems and support structures also used to play an important role regarding the prevention and solution of problems in the family and community. Such matters were viewed and handled communialistically, but with the fluctuation in the control systems and support structures and the simultaneous change of communialistic relations and relationships amongst people, a major force in alleviating these issues is no longer necessarily available. The result is that a continuous state of intrigue and unresolved conflict can exist within the group (such as the family) and the community. Disorder invariably sets in, and the family no longer provides the secure framework for integrated communal and cosmological life. In fact, the family becomes a problem within itself and can therefore not fulfil a mediating role where and when feuds arise.

The deconstruction of unhealthy control systems, hierarchical structures and authoritative power relationships is continuously necessary, but the lack of proper reconstruction leaves voids within the muta, resulting in disorder and indiscipline where Vhuthu seems to be relativised.

Van Wijk (1984) says that there is another area where the traditional African view of a person as a communalistic and cosmological being could cause problems:

The communal African view of society is well known and has often been praised . this concept with its strong sense of solidarity and mutual responsibility has been a major factor in the survival of the race on a hard continent like Africa. The communal view of person has also led to the great emphasis on Conformity . Conformity is considered necessary for the survival of the community. Deviations from the norm are highly dangerous. Peace and happiness are ensured by conformity to the customs and folkways of the community ... Individual ability is recognized but beyond a certain point it may threaten stability and even survival itself. The communal emphasis has caused many Africans to feel the centre of their identity as being outside themselves, in the community. This has diminished the amount of inner individual awareness and has hampered individual initiative ... In a time of much selfish individualism the great sense of community and coherence in African society is certainly impressive. At the same time there is a great need in modern society for individual responsibility and initiative. A high degree of individual inwardness is required. (pp. 183-184)

Van Wijk is correct in referring to compromise and conservation in the interest of the group, but as much as 'I am, because we are' and 'we are, therefore I am' or 'I belong, therefore I am' is true, it does not de-identify the individual. In fact, the individual finds an extended identity through the group (Du Toit 2005:852).

A sad side to Vhuthu presented itself during the early 1990s. Incidents of misfortune such as theft, rape and muti-murders took place all over the then Venda territory. In the spirit of Vhuthu, whole communities stood together, reported the matters to headmen who, in turn, consulted sangomas. The 'guilty' parties were identified as 'witches' and punished by the respective community groups of residents at Manamani, Ramukuba and Tshisaulu by burning down the house of a suspected family, hacking an old man to death using hoes, knobkieries and pangas and stoning a youngster until he lay paralysed. Theft, rape and muti-murders are despicable deeds, but communal 'justice' was handed out to potentially innocent people because they were criminalised without due process.

I was pastorally involved in these and numerous other similar cases. What I found was that the very same people who killed the 'wrongdoers' in many instances attended the funerals of the respective deceased and did so in large numbers.

During the build-up to the 1994 elections, many South Africans experienced anxiety, fear and trepidation. When the outcome was peaceful, it was considered 'a miracle of God'.

However, whilst the honour is God's, in the Northern parts of the Limpopo Province there was such a strong thrust of Vhuthu, Ubuntu and Botho that the nature of the elections was never in doubt. Church leaders, party-political organisers, the civics, traditional leaders, the army, police and students worked tirelessly together to inform the public about voting procedures whilst calling for calm. Church services, weddings, funerals, sporting events and all other occasions were used to inspire people to act maturely and responsibly.

During that time, I arrived at a funeral where crowds of mourners waved flags and banners of the ANC, AZAPO, PAC and SACP, toy-toyed and sang struggle songs. A well-known and 'militant' member of the PAC welcomed me and guided me through the crowd to my seat. When the programme director introduced me before the sermon, he used the opportunity to tell those present to take care during the elections as much as they have taken care of me that day. A lady started a song and all joined in singing the Afrikaans hymn 'Ons is almal hier tesaam [We are all here together ...].

These examples do in fact reflect that Vhuthu is not confined to the muta but does permeate clan, community and general life. The foundations of Vhuthu nevertheless lie in the muta.

Unfortunately, in spite of the efforts of former President Mandela, Emeritus Archbishop Tutu and many others, this spirit of Vhuthu, Ubuntu and Botho slowly but surely lost momentum because of the divisive pronouncements and actions of political leaders of all parties, the tragic increase in petty and serious crimes, violence, xenophobia, inadequate service delivery, unemployment, poverty and the continued experience of previous and reversed racism, genderism, sexism, disablism and other forms of discrimination. This does not bode well for Vhuthu, Ubuntu and Botho.

However, as much as Vhuthu might be disturbed by external and internal factors, it does not mean that its dynamics are becoming extinct. Numerous vestiges of the past remain (for example, traditional communal family dancing), others adapt (for example, combining traditional with so-called 'white' family weddings) and many new expressions appear in accordance with changing demographics and times as well as global influences (for example, the family gathering around the television instead of in the courtyard).

Conclusion

In this article, I ventured into the autoethnographic journey of a practical theologian, constructing the potential and problematics of Vhuthu in the muta. These personal experiences and interpretations were integrated with relevant literature and works of art.

Discussing Vhuthu in the muta places the emphasis on the local and embodied context. It is within this concrete framework where Vhuthu finds its primary application as a way of life. The praxis of Vhuthu in the muta is therefore one of many examples of the point of departure for practical theology in its effort to autoethnographically try to understand and reflect upon the micro dynamics of life.

In agreement with Miller-McLemore (2012a:16), I therefore believe that the study of Vhuthu and related concepts such as Ubuntu and Botho provide an opportunity for practical theology to be autoethnographically involved in researching the locally lived experiences of families, communities, churches and other religious and secular institutions. Simultaneously, it allows one the opportunity to address the plight of marginalized and vulnerable men, women, children and disabled people who continue to suffer under racism, genderism, sexism, disablism, poverty, unemployment, violence and xenophobia.

It is from these micro-contexts that practical theology can move towards the development of applicable methods of study, curriculum and the discipline as a whole. Of course, it can continue the iterative spiral between context, text, context, et cetera.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Achebe, C., 1958, Things fall apart, Heinemann, London. [ Links ]

Bosch, D., 1974, Het evangelie in Afrikaans gewaad, Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Broodryk J., 2002. Ubuntu: Life lessons from Africa, Ubuntu School of Philosophy, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Du Toit, C., 2005, 'Implications of a techno scientific culture on personhood in Africa and in the West', Hervormde Teologiese Studies 61(3), 829-860. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v61i3.468 [ Links ]

Ellis, C., Adams T.E. & Bochner A.P., 2011, 'Autoethnography: An overview', Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12(1), 2-18. [ Links ]

Farisani, T.S., 1988, Justice in my tears, Africa World Press, New Jersey. [ Links ]

Hanekom, C., 1979, 'n Verkenning van enkele kontra-akkulturatiewe houdinge en verskynsels in Afrika', South African Journal of Ethnography 2, 1-12. [ Links ]

Holt N.L., 2003, 'Representation, legitimation, and autoethnography: An autoethnographic writing story', International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2(1), 18-28. [ Links ]

Kelsey, D.H., 2009, Eccentric existence: A theological anthropology, vol. 1 & 2, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville. [ Links ]

Kudadjie, J. & Osei, J., 1998, 'Understanding African cosmology', in C.W. du Toit (ed.), Faith, science and African culture: African cosmology and Africa's contribution to science, pp. 99-106, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Manganyi, N.C., 1973, Being-black-in-the-world, Spro-cas/Raven, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mashige, M.C., 1996, 'Politics and aesthetics in contemporary black South African poetry', MA dissertation, Department of English, Rand Afrikaans University. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S., 1969, African religions and philosophy, Heinemann, London. [ Links ]

Meiring, J.J.S., 2014, 'Theology in the flesh: Exploring the corporeal turn from a Southern African perspective', PhD thesis, Faculty of Theology, Vrije Universiteit. [ Links ]

Miller-McLemore,B.J., 2012, 'Introduction', in B.J. Miller-McLemore (ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to practical theology, pp. 12-29, Blackwell, Chichester. [ Links ]

Muloiwa, R., 1999, 'Ubuntu: The concept in a multicultural medical context', The Big Picture 1(1), 30. [ Links ]

Myburgh, AC., 1981, Anthropology for Southern Africa, Van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Neluvhalani M.C., 1987, fa Lashu la Maambele, Sasavona, Braamfontien. [ Links ]

Pace, S., 2012, 'Writing the self into research: Using grounded theory analytic strategies in autoethnography', Creativity: Cognitive, Social and Cultural Perspectives 13, 1-15. [ Links ]

Setiloane, G., 1986, 'Human rights and values: An African assessment in the search for a consensus', Scriptura 18, 41-55. [ Links ]

Setiloane, G.M., 1998, 'Towards a biocentric theology and ethic: Via Africa', in C.W. du Toit (ed.), Faith science and African culture: African cosmology and Africa's contribution to science, pp. 73-84, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Setiloane G.M., 2000, African theology: An introduction, Lux Verbi, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Shutte, A., 2001, Ubuntu: An ethic for a New South Africa, Cluster Publications, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Soyinka, W., 1976, Myth, literature and the African world, Cambridge University Press, London. [ Links ]

Van Deventer, W.V., 1988, Ek draai saam, Leach, Louis Trichardt. [ Links ]

Van Deventer W.V., 1991, A congregation in a world of poverty, Theologia Viatorum, Special Issue 1. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, A.S., 1982, Dominee, are you listening to the drums? Tafelberg, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Van Warmelo, N.J., 1989, Venda Dictionary, Van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Van Wijk, J.A., 1984, 'Liberation theology in the African context', in J.W. Hofmeyer & W.S.Vorster (eds.), New faces of Africa, pp. 183-186, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Vilakazi, H., 1998, 'Land and science: Nature, God and ecology in African thought', in C.W. du Toit (ed.), Faith, science and African culture: African cosmology and Africa's contribution to science, pp. 107-116, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Ziervogel, D., Wentzel, P.J. & Makuya, T.N., 1961, A handbook of the Venda language, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Wilhelm van Deventer

PO Box 1197, Potchefstroom 2520

South Africa

wilhelmvand@lantic.net

Received: 21 Feb. 2015

Accepted: 01 Apr. 2015

Published: 18 June 2015

Dr Wilhelm van Deventer is a Senior Research Fellow at the Ubuntu Research Project, University of Pretoria. Research Participant in the Ubuntu-Research project of the University of Pretoria.