Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.36 no.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v36i1.1464

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The use of biblical themes in the debate concerning the xenophobic attacks in South Africa

Zorodzai Dube

Department of New Testament, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The study draws from the ideas of Jürgen Habermas, Daniel Trotter and Christian Fuchs, Zizi Papacharissis, Yochai Benkler and Christian Fuchs to investigate the use of social media as a platform to express ideas against xenophobic-related attacks in South Africa (April 2015-May 2015). The data was collected from twitter, YouTube and Facebook. Most views came from the Facebook platform called 'Stop xenophobia'. Using ATLAS.ti, software for qualitative research, the data was coded into interpretive variables or categories. The results show that themes such as hospitality, morality, creation and ethics received highest frequency as reasons to condemn xenophobia. The research further reveals that the social media data is much candid in comparison to state controlled media, where views and ideas were censored to protect the economic and public image of the country. Unlike the controlled government outlets which focus on the possible correlation between xenophobic attacks to economic outlook, the social media focuses on moral and ethical issues - issues that define our collective as human beings and tackles xenophobia from the perspective of ethics and shared human values.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: This study is interdisciplinary in nature due to the use of theories in media studies and social sciences to investigate the use of biblical themes in the fight against xenophobia.

Introduction

The newspapers attributed the outbreak of the xenophobic attacks that occurred on the 15th of April 2015 to the unfortunate statements by the Zulu King, Goodwill Zwelethini, who during one of the festivals in his village, bemoans the loss of Zulu morality because of foreigners. Zwelithini accused foreigners of diluting the Zulu culture and compared the foreign nationals to lice that crawl everywhere and, he sees it as the duty of his people to deal with them (Rantao 2015). The exact words of the king (in April 2015) were recorded and printed, which say:

[W]e talk of people [South Africans] who do not want to listen, who do not want to work, who are thieves, child rapists and house breakers ... When foreigners look at them, they will say let us exploit the nation of idiots. As I speak you find their unsightly goods hanging all over or shops, they dirty our streets. We cannot even recognise which shop is which, there are foreigners everywhere. I know it is hard for other politicians to challenge this because they are after their votes. Please forgive me, but this is my responsibility, I must talk, I cannot wait for five years to say this. As king of the Zulu Nation ... I will not keep quiet when our country is led by people who have no opinion. It is time to say something. I ask our government to help us to fix our own problems, help us find our own solutions. We ask foreign nationals to pack their belongings and go back to their countries (loud cheers). (De Vos 2015:n.p.)

A matchstick was lit and xenophobic attacks spread like veld fire from Durban to Gauteng, resulting in thousands of foreign nationals displaced and their shops looted. Approximately five people died and 20 000 were displaced and, many left for their countries fearing for their lives (Essa & Patel 2015).

The response from the government's side which seemed unprepared and uncoordinated was very slow. Even when the government responded, the focus was on preserving public image and trade across the continent and not showing remorse over the lost lives. Lack of policy coordination on the government side was shown when the Secretary General of the ruling party, African National Congress, Gwede Mantashe came on air and suggested that all undocumented foreigners must be put in refugee camps giving the government time to review its immigration policies (Quintal 2015). Up to now, Mantashe has not been publicly reprimanded, except for the indirect and conflicting response from some members of the ruling party that they do not support his idea. Instead, veiled criticisms were given by the mayor of Ethikwini, James Khumalo and the mayor of Durban, Senzo Mchunu, who condemned the attacks; accusing those who attack foreigners as 'not South African'. Malusi Gigaba, the Minister of Home Affairs added his voice saying the priority is to protect all foreigners and not to witch-hunt illegal migrants (Bulbulia 2015).

Unfortunately the much expected speech by His Excellence, the President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, was received as a vailed justification of the xenophobic attacks, after Zuma, during the Freedom Day asked, 'Why are foreigners here in South Africa and not in their own countries'. This angered many foreign diplomats;1 for example, in response the Zimbabwean Minister of Information, Jonathan Moyo wrote, '[f]t comes across as an unfortunate justification of the gruesome xenophobic attacks even if unintentionally so!' (Mzileni 2015). Awkwardly, the church was silent for almost a week and, later organised marches in Durban and Gauteng.

This study looks into the online conversations, especially the reasons forwarded to oppose the xenophobic attacks. Social media provided uncensored news and, unlike government-controlled media outlets, all horrific pictures and gruesome images were posted. Social media had a more robust and honest debate. For example, social media had pictures of people, including children, being burnt alive - events that were avoided by the state media because of their sensitivity and propensity towards fuelling the attacks. The difference in content and perspective was clear if one juxtaposes the Facebook, YouTube discussion to any South African Broadcast Cooperation (SABC) channel. This study locates itself in the midst of this uncensored debate, looking into how the religious language during the discussions, was evoked as rhetoric that helped in self-regulating and consoling, vis-à-vis the state controlled media where the information was regulated and people are still asking questions about what happened.

Social media and public debate

Despite the church's delay to denounce xenophobia, the social media was buzzing with religious sentiments against xenophobia. Why social media? Jürgen Habermas (1992:421), who wrote from the context of the emergency of modern states in Europe and the role of the media, is known for connecting media to democratic processes. Habermas argues that the media is a critical tool towards public critical democratic debate by providing public platform upon which the community engages in critical, self-regulating dialogue which will result in public consensus (Habermas 1992:432, 1987:42). Habermas was battling with the societal shift from feudal and monarchy-based institutions, which were viewed as authoritarian to democratic institutions based on collective participation. Habermas' most important contribution is the idea that, besides providing a public plural platform, the public space is a place where asymmetric power hierarchies are critically engaged.

Habermas' theory laid the foundation upon which different authors view the media, especially the new technologies such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, as enablers of a more critical, alternative voice. For example, Zizi Papacharissis (2009:244) says, by allowing people to post their own views on Facebook or YouTube, the social media provides a platform for 'dissent voices with a public agenda'. The social media converts individuals from mere followers to active contributors, speakers and participants in a conversation (Benkler 2006:2013). Christian Fuchs (2014:57) adds that the social media criticises asymmetric material and hegemonic discourses by making leaders accountable to the public.

An assessment of the role of the social media during the xenophobic attacks in South Africa gives credence to the perspective of Zizi Papacharissis (2009:244), Yochai Benkler (2006:213) and Christian Fuchs (2014:57). The public used the social media as platform to condemn those who were perpetrating violence; criticising the government and actively participating in the discussions. From the television news, the state's perspective was to deny the report and the extent of violence by presenting the view that South Africa is a safe destination. As such the diplomatic and economic factors were dominant variables in the way the state approached the xenophobic attacks. Thus, in protecting its image, a number of events that happened during the attacks were not reported. The need to lessen the extent is exemplified by the debate that arouse after a journalist published the horrific and gruesome killing of Immanuel Sithole, a Mozambique national, in Johannesburg. Whilst the social media already had all the details, the state media was still debating the ethics of photographing the last moments of a dying person -must the truth be told or in telling the truth, we negatively affect the state's public image (Tromp & Oatway 2015). To add another twist to the debate, President Zuma, instead of giving condolences, he focused on the issue that the murdered Sithole had no legal documents, an issue of less priority, given that someone had already died. However Zuma's remark shows the preoccupation of the state vis-ä-vis the social media. Whilst the social media was sympathetic and raised matters concerning our collective humanity in stopping the xenophobia, the state was preoccupied with legal issues - projecting the xenophobia as a legal and economic matter. I noted that, in comparison to television or radio channels, the social media provided more detail and robust debate about xenophobia. By their very nature, the television and radio stations cannot accommodate the voices of all citizens.

Religious themes during the xenophobic attacks

In agreement with Jürgen Habermas (1992:432), Daniel Trotter and Christian Fuchs (2015:1), Zizi Papacharissis(2009:244), and Yochai Benkler (2006:213) the study focuses, mainly, on themes that developed from the online conversation concerning the xenophobic debate, especially, the page, Stop Xenophobia (Stop Xenophobia 2015:n) which quickly accrued 5552 adherents. Each day more contributors followed the conversations. This lends the social media as an open terrain, rich with diverse voices and often, more elaborate discussions concerning particular issues. In following the social media, I am interested in how religious language was deployed to make sense of the attacks. I observed from the social media platform that there were instances when the contributors would put a specific biblical verse, but there were also instances where ethical values were emphasized, and it was easy to infer the theological and biblical discursive motivation. In addition, I observed that the frequency at which the map of Africa was posted with various inscriptions, such as, human faces - mostly black, or words such as 'Africa, we are one' reinforced the idea that black Africans need to unite and desist from violence. The map of Africa does not only show geography, but the permeating themes deployed in fighting xenophobia.

It seems in agreement with Jürgen Habermas (1992:432), Daniel Trotter and Christian Fuchs (2015:1), Zizi Papacharissis (2009:244), and Yochai Benkler (2006:213). The real debate concerning xenophobia was discussed through the social media and not through the television and radio platforms. This shows that the media is a plural platform that allows people to come to their own collective resolution. In this case, the social media provided the platform for public conservation, a platform where people began to talk to each other in a personal way. The following themes from social media show that the reasons against xenophobia were more related to people being human; our collective responsibility, our humanness, and not economy or nationality. Mostly, responses would come after someone posted an image or statement of update regarding the attacks.

ATLAS.i

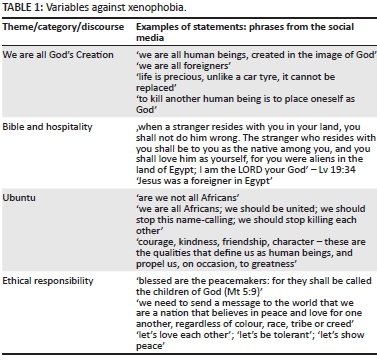

I used ATLAS.ti, a social science research software tool that allows the researcher to analyse data and find its internal categories. In using this tool, data from various social media that relate to the topic were collected (see Table 1). I specifically collected paragraphs, sentences and phrases that that people wrote in condemning the xenophobic attacks. In the next stage, the data was grouped according to frequency of particular themes, which also indicates the discursive perspective of the contributors. Table 1 chronologically produced the following themes and discourses which were used to condemn xenophobia.

Creation forbids xenophobia

The variable that receives the highest frequency is the notion that we are all equal creatures made by God. The social media platform had statements such as 'life is precious, unlike a car tyre, it cannot be replaced'. With regards to creation, the most interesting statement was 'we are all human beings, created in the image of God'. The statement, 'we are all created in the image of God', reminded people about the basics concerning being human - we are all creatures from a loving God. From this perspective, xenophobia shrouded our direct view towards each other - we are all creatures of God. Theology always teaches these basic human tenants, but they do not make sense unless understood from a particular social event. Xenophobia in South Africa was acted out from the context of fighting over the few economic resources, especially in the townships. From this context, competition for the few material resources replaced our common humanity to such an extent that people saw each other as enemies and not as equal humans. In a persuasive article titled 'The West and the rest: Discourse and power', Stuart Hall (1996:186) claims that at the heart of modernity was a displaced concept of being human. People from the rest of the world were discursively labelled as lesser humans, which gave the impetus for imperialism and colonisation. Arguably, though Hall discusses from a macro-level, the xenophobia events give us a mini drama around which our common humanity can be shrouded by our unguarded and unreasonable quest for survival. I noted that the creation theme was deployed in the xenophobic attacks as a narrative that pulls us together.

But what is common in us being human? I expected social media contributors to expound on the Genesis account, but they did not. Instead, they wrote, saying 'we are all foreigners', a statement which, in my view removes national boundaries and ethnic borders - inscribing a common identity as human on everyone - which evokes the genesis account of God creating the world and placing human beings in the world with a command, 'Be fruitful and multiply. Fill the earth and govern it. Reign over the fish in the sea, the birds in the sky, and all the animals that scurry along the ground' (Gn 1:28). Implicitly, the social media contributors regarded xenophobia as militating against the mundane concept of being human, which is roaming about God's world, regarding each other as fellow humans and not as enemies. Importantly, the people use the Bible subjectively; their experiences determine how meaning is created. The text is not independent from the experiences of the people; it is part of articulating collective experience and identity formation.

With regards to how the theme of creation was used as a counter-narrative, Zizi Papacharissis' (2009:244) reflections are applicable. Papacharissis sees the social media as a platform that accords 'dissent with a public agenda'. This means that we can understand the manner in which the theme of creation was used as counter-narrative or ideology. To understand the theme of creation as a counter-narrative we should place social media alongside the government-controlled media where politicians such as Mantashe regard immigrants as a menace, or King Zwelithini who regards immigrants as cockroaches that need to be swept away. Whilst politicians discuss the issue of immigrants from an economic perspective, the social media countered the narrative by contesting evaluation and categorisation of people based on commercial value. From this perspective, as Papacharissis says, the media functioned as a platform for 'dissent with a public agenda'.

The Bible teaches hospitality to foreigners

The second variable is hospitality. In addition to the theme of creation, hospitality was used as a theme to fight xenophobia. A verse (Lv 19: 33-34) was posted, to which the followers responded with 'amen' or 'yes'. The Old Testament text in Leviticus 19:33-34 says:

[ W]hen a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not do him wrong. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt; I am the LORD your God.

Noticeably, people interpret the scriptures based on their experience. Interestingly, all the contributors seem to share a common understanding of the verse; there was none who said the verse refers to an ancient culture and context. In many of his writing, Gerald West (West 2000:30, cf. Maluleke 2000:92) makes us aware of the difference between the reading practices of the ordinary reader and the trained reader. Typically, at seminaries and faculties of theology, the verse would have been subjected to historical critical theories and other textual skills to determine its meaning. Conversely, the contributors read the Bible subjectively, which West (2000:30) calls 'reading in front'. On the social media the text was directly appropriated as having direct meaning to the current events - the Bible agrees with people's experiences. This does not refer to a literal reading, because the people were not interested in reading the text; instead, they were interested in its ability to be part of the experience and storytelling. The meaning of the above verse was very clear - foreigners must not be mistreated and must be treated as natives. From this plain meaning, perpetrators of xenophobia violated the authority of God's Word and, though not formally charged in our country's courts, God has already proclaimed a verdict - guilty. Masiiwa Gunda (2010:104) observes that, besides being the Word of God, the Bible is clandestinely deployed as a tool to judge others. In the case of xenophobia, the Bible took the role of condemning the attackers.

Why use the Bible? As answer, xenophobic attacks which were mostly targeted towards fellow black people, presents itself as the collapse of normalcy or collective worldview; thus an inversion of chaos. Thus, evoking the authority of the Bible is similar to evoking the authority of the gods. Implicitly, the evocation of the scriptures may suggest the loss of trust towards the local authority to protect and provide order. In this regard, the deployment of the Bible aimed at reconstructing the torn cosmology. Gerald West (2000:30) would say, with regards to the public treatment of the Bible, it is powerful even when it is a closed book; to open it further unleashes its potent power. In most African societies, the Bible is the final tool upon which people can swear or fight misfortunes, thus, its invocation means the final say over the particular matter (Vengeyi 2013:29).

Using the media to wrestle and debate collective issues agrees with Yochai Benkler (2006:213), who says the media offer the ordinary people the platform to be active citizens. Through the social media people cease from being passive listeners under the mercy of hegemonic aristocratic media to being creators, protestors and engaged citizens. Journalist and the politicians no longer have a monopoly over ideas and the public space. Social media offered the opportunity to debate and engage in issues that affect us all.

Ubuntu is biblical

The third variable that received high frequency is the notion of ubuntu. In addition to placing the Bible at the centre of the discussion, implicit moral values were shared, as if to remind ourselves of our collective moral degeneration that had come to surface through the xenophobic attacks. The catch phrases which were repeated were 'are we not all Africans' or some would be more explicit by writing saying, 'we are all Africans'; 'we should be united'; 'we should stop this name-calling'; 'we should stop killing each other'. The repeated term here is 'African', which raises the question, what is it about being African that has been violated by xenophobic attacks? African philosophers occasionally want to remind the world that there was a common African ethos, perhaps a renaissance, which was disrupted by colonisation -ubuntu. Africans in general love to pride and distinguish themselves saying that they have a collective approach to life vis-à-vis Western individualism (Samkange 1980:106). The former president of Tanzania, Nyerere, and to some extent, Archbishop Desmond Tutu (Tutu 1999:6; Vervliet 2009:20) popularised ubuntu as a unique African approach to life. At its core, ubuntu teaches the dignity of all people, thus working as a counter discourse against dehumanising statements from missionaries, anthropologists and travellers, who had categorised Africans as less human (Wiredu 2008:332). It simply means 'I am because you are' - referring to the fact that well-being is intertwined and communally shared. If traced from the period of colonialism and the characteristics of that period, which was the desire for African renaissance, then, there is a link to the philosophical intent of ubuntu to the questions of colour; the need to assert African pride. During the same period, in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a general upbeat about the future of Africa, which was seen in rhetoric that proposes the United States of Africa (Asante 2013). Also, there was a strong Afro-centric support within the academics, which was seen in the revisit and re-appropriation of African tradition values and beliefs; a refutation of previous erroneous Western epistemologies about Africa and her beliefs. Within pop-culture, the upbeat sentiments was captured through the phrase 'black is beautiful'. In South Africa, ubuntu has been generally used to refer to the political philosophy of 'togetherness' vis-ä-vis the apartheid political philosophy of division (Van der Merwe & Du Plessis 2004:63).

Sometimes, in theological discourses ubuntu is construed as equal to the biblical concept of kinship and hospitality; thus, when referring to ubuntu, some scholars easily synonymise the concept with some Mediterranean biblical values (Tutu 1999:6; Vervliet 2009:20). The idea that ubuntu lends itself close to biblical moral values was evident from the website as contributors wrote, saying, 'courage, kindness, friendship, character - these are the qualities that define us as human beings and propel us, on occasion, to greatness.' I deduced that, as a country and continent, the xenophobic attacks, reversed the gains, in term of civility that Africa has accumulated - reversing the last straw of humanness, thus leaving Africa with her old colonial tags of barbaric, uncouth and animalistic. By killing each other, Africa reclaims her negative reputation as a 'dark continent', and unpredictable. Hence, the phrase, 'are we not Africans' sought to revive the residue of respect which is associated with ubuntu. On the social media, the map of Africa dripping with blood graphically depicts the pain, but equally, the shame that the continent has attracted.

In my view, the evocation of the ubuntu ideology can be understood from the perspective of various facets of shame. Psychologists such as L. Wurmser (1987:64) and G.O. Gabbard (1989:527) say a shameful person may exhibit narcissist tendencies by trying to present a self that is opposite to the internalised shameful self. This can be described as a cover-up or self-denial. Equally, one can deduce that, collectively, by reinforcing and evoking ubuntu, as a society, we somehow depict a narcissist public image of trying to cover-up the shame that resulted from the xenophobic attacks.

Importantly the notion of ubuntu makes us think of Mantashe's words when he said undocumented foreigners must be put in enclosed camp to allow the government to decide on their fate. Mantashe's sentiments can be seen as erecting identity categories based on nationality and class, given that all undocumented foreigners come from poor backgrounds and countries. In view of this, the social media used the idea of ubuntu as a counter-narrative. By arguing that we are all Africans and that we should be united, the ubuntu ideology functioned, as Zizi Papacharissis says that social media offers a platform of 'dissent with a public agenda'.

People have an ethical responsibility

The fourth variable is ethics - mostly, veiled in ethical and moral teachings, such as love, compassion and peace.

Whilst these ethical principles are general to all humankind and religions, the contributions added biblical verses. For example one wrote, 'blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God' (Mt 5:9). Someone added, saying, 'we need to send a message to the world that we are a nation that believe in peace and love for one another, regardless of colour, race, tribe or creed'. People wrote moral imperatives and, implicitly, cited a biblical text or a person who represented such. For example, moral statements that carry the idea of love and peace were associated with the face of Jesus or Mandela. Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama were also cited and their images were associated with peace and tolerance.

We can view the ethical statements from the perspective of Yochai Benkler (2006:213) as statements that show people actively rebuilding their moral landscape. The ethical statements were usually short and to the point, for example, 'let's love each other', 'let's be tolerant', 'let's show peace'. I read the ethical and moral statements as narratives that reflect something about us - Africans, that is, there is a moral bankruptcy that is evidenced by the attacks. Thus, the moral teachings about love and peace are basic moral teachings which ground all human beings. When someone writes to another reminding them that they are human being, by implication the xenophobic attacks necessitated a re-orientation concerning basic human traits. What is moral and socially acceptable comes from the society and it is the duty of the society to constantly remind its inhabitancy of the rule and norms. In this regards, the attacks evoked the moral and ethical re-orientation

Conclusion and remarks

The study noted that during the xenophobic attacks the social media were a platform of protest and engagement. People used the social media to contest particular ideologies and narratives which they see as limiting and excluding, by reminding each other of terms such as ubuntu and creation which were seen as inclusive identity markers. Whilst the state media was concerned with censoring content to preserve the state's economic and public image, the social media circulated unedited events which allowed people to critically debate the events as they happened. The social media focused on moral and humane reasons against the attacks. In self-regulating and active participation, the media had alternative themes against xenophobia, such as 'we are equal God's creations', 'we share a moral obligation of ubuntu', 'we have a God who demands us to love our neighbours' and 'we must be ethically responsible towards each other'. Notably, there was no reference to foreigners being illegal or taking of jobs; instead, the focus was on sharing the pain of those who were victimised.

A number of issues surface: first, people might differ in terms of origin, but killing another person was seen as inhumane. Secondly, the social media concentrated more on humane and moral issues - as human beings we need to feel the pain of others. Third, despite cultural differences, virtues such as peace, love and tolerance were shared, disregarding the legal issues around the foreigners. In conclusion, the study shows that human beings, despite their shortcomings, share basic human traits of love, hospitality and tolerance and, when extreme elements among us distort our common humanness, we stand together in one voice to condemn, overlooking the economic and legal issues.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Asante, M.K., 2013, 'United States of Africa makes sense', viewed 19 April 2015, from http://www.bdlive.co.za/africa/africanperspectives/2013/04/17/a-united-states-of-africa-makes-sense [ Links ]

Bulbulia, M.I., 2015, 'Who's saying what about xenophobia from the Zulu King to the eThekwini mayor', viewed 15 August 2015, from http://www.thedailyvox.co.za/whos-saying-what-about-xenophobia-from-the-zulu-king-to-the-ethekwini-mayor/ [ Links ]

Benkler, Y., 2006, The wealth of networks, Yale University Press, New Haven. [ Links ]

De Vos, P., 2015, 'Xenophobia statement: Is King Zwelitini guilty of hate speech', viewed 16 August 2015, from http://constitutionallyspeaking.co.za/xenophobic-statement-is-king-zwelithini-guilty-of-hate-speech/ [ Links ]

Essa, A., & Patel, K., 2015, 'South Africa and Nigeria spar over xenophobia violence', viewed 28 April 2015, from http://mg.co.za/article/2015-04-28-south-africa-and-nigeria-spar-over-xenophobic-violence [ Links ]

Fuchs, C., 2014, 'Social media and the public sphere', TripleC, 12(1):57-101. [ Links ]

Gabbard G.O., 1989, 'Subtypes of narcissistic personality disorder', Bulletin Menninger Clinic 53, 527-532. PMID: 2819295 [ Links ]

Gunda, M.R., 2010, The Bible and homosexuality in Zimbabwe, UBP, Bamberg. [ Links ]

Habermas J., 1992, 'Further reflections on the public sphere', in C. Calhoun (ed.), Habermas and the public sphere, pp. 421-461, The MIT Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Habermas, J., 1987, Theory of communicative action Volume two: Liveworld and system: A critique of functionalist reason, transl. Thomas A. McCarthy, Beacon Press, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Hall, S., 1996, 'The West and the rest: Discourse and power', in S. Hall & D. Held (eds.), Modernity: An introduction to modern societies, pp. 186-224, Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Maluleke, T.S., 2000, 'Bible among the African Christians: A missiological perspective', in T. Okure (ed.), To cast fire upon the earth: Bible and mission collaborating in today's multicultural global context, pp. 87-112, Cluster Publications, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Mzileni, P., 2015, 'Zuma's Freedom Day speech appears to justify xenophobia - Zim Minister', viewed 28 April 2015, from http://www.powerfm.co.za/news/news/zumas-freedom-day-speech-appears-to-justify-xenophobia-zim-minister [ Links ]

Papacharissis, Z., 2009, 'The virtual space 2.0: The Internet, the public space and beyond', in A. drew Chadwick & P. Howard (eds.), Routledge handbook of internet politics, pp. 230-245, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Quintal, G., 2015, 'SA needs refugee camps - Mantashe', viewed 28 April 2015, from http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/SA-needs-refugee-camps-Mantashe-20150412 [ Links ]

Rantao, J., 2015, 'Zwelitini, The elephant in the room', viewed 28 April 2015, from http://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/zwelithini-the-elephant-in-the-room-1.1850546#.VT_nkSGqqko [ Links ]

Samkange, S.J.T., 1980, Hunhuism or Ubuntuism: A Zimbabwe indigenous political philosophy, Graham Publishing, Harare. [ Links ]

Stop Xenophobia, 2015, https://www.facebook.com/stopxenophobia/info/?tab=page_info. Accessed 28 April 2015. [ Links ]

Tutu, D., 1999, No future without forgiveness, Rider, London. [ Links ]

Tromp, B., & Oatway, J., 2015, 'The brutal murder of Emmanuel Sithole', viewed 29 April 2015, from http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/2015/04/19/the-brutal-death-of-emmanuel-sithole1 [ Links ]

Trotter, D & Fuchs, C., 2015, 'Theorising social media, politics and state: An introduction', in D. Trotter & C. Fuchs (eds.), Social media, politics and the state: Protests, revolutions, riots, crime and policing in the age of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, Routledge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, C.G. & Du Plessis, J.E., 2004, Introduction to the law of South Africa, Kluwer Law International, The Hague. [ Links ]

Vengeyi, O., 2013, 'Zimbabwean Pentecostal prophets', in E. Chitando & R. Gunda (eds.), Prophets, profit and the Bible in Zimbabwe: Festschrift for Aynos Masocha Moyo, pp. 29-54, Bamberg Press, Bamberg. [ Links ]

Vervliet, C., 2009, The human person, African Ubuntu and the dialogue of civilisations, Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd., London. [ Links ]

West, G., 2000, 'Mapping African Biblical interpretation: A tentative sketch', in G. West & M. Dube (eds.), The Bible in Africa, pp. 29-53, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Wiredu, K., 2008, 'Social philosophy in postcolonial Africa: Some preliminaries concerning communalism and communitarianism', South African Journal of Philosophy 27(4), 332-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sajpem.v27i4.31522 [ Links ]

Wurmser L., 1987, 'Shame, the veiled companion of narcissism', in D.L. Nathanson (ed.), The many faces of shame, pp. 64-92, Guilford, New York. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Zorodzai Dube

Office 1-47, Department of New Testament, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria

Lynwood Road 0003

South Africa

zorodube@yahoo.com

Received: 01 May 2015

Accepted: 04 Sept. 2015

Published: 04 Nov. 2015

1 Embassies with affected people, such as Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, Angola, Cameroon, and Congo raised their dismay concerning the xenophobic attacks.