Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Verbum et Ecclesia

versión On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versión impresa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.36 no.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/VE.V36I1.1391

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Reading the Bible in the 21st century: Some hermeneutical principles: Part 1

Dirk van der Merwe

Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Many books and articles have been published over several decades on 'biblical hermeneutics' to capture the epistemology of biblical hermeneutics and the phenomenology of interpretation, communication and language in order to direct the Bible reader how to read the ancient texts, assembled in the Bible, sensibly. The first part of this essay looks briefly into the history of biblical hermeneutics of the past century in order to generate an orientation of how 'biblical hermeneutics' was regarded and applied as well as to constitute an environment for the investigation to follow in the rest of this essay and in a succeeding essay. In the second part of this essay, a few hermeneutical approaches are analysed in order to recommend a way forward for the dynamic analysis and interpretation (ερμηνεία) of biblical texts. This prepares the stage for the recommendation of two extra textures or aspects to be incorporated in the hermeneutical process, to be investigated in a succeeding essay.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: This article briefly orientates the reader about the paradigm shifts concerning biblical hermeneutics over the previous half century. It challenges the holistic approach to incorporate spirituality and the embodiment of biblical texts in the hermeneutical process. Disciplines involved are hermeneutics and methodology, theology and spirituality.

Introduction

The purpose of the website, Early Christian writings, '... is to explain and explore some of the theories offered up by contemporary scholars on the historical Jesus and the origins of the Christian religion'. (Historical Jesus theories n.d.) This website expresses a diversity of historical Jesus theories offered by the authors of the Jesus Seminar: 'Jesus the myth: heavenly Christ', 'Jesus the myth: Man of the indefinite past', 'Jesus the Hellenistic hero', 'Jesus the revolutionary', 'Jesus the wisdom sage', 'Jesus the man of the Spirit', 'Jesus the prophet of social change', 'Jesus the apocalyptic prophet' and 'Jesus the saviour'. This is only one example of extreme diversities in biblical interpretation (Craig n.d.). This variety of scholarly interpretations and descriptions of Jesus' identity underlines the importance for solid biblical hermeneutics.

Over the past decades, many books and articles have been published on 'biblical hermeneutics'1 to capture the epistemology of hermeneutics2 and the phenomenology of interpretation, communication and language in order to direct the Bible reader on how to read and interpret the ancient texts assembled in the Bible. Important advances in hermeneutical theory took place during the past few decades (Tate 2011; Virkler & Ayayo [1981] 2007:13; cf. Hays 2007:10; Osborne 2010:15-16),3 and hermeneutical theory '...continues to grow more complex and differentiated' (Oeming 2006:ix). To understand a text is very complex but also exciting and involves aspects such as the author, the text, the reader, the subject matter in the text and the dialogical process. Each of these aspects is connected to its own discourse and set of rules (ibid:ix).

This essay argues for a comprehensive hermeneutical approach in the investigation of biblical texts. The proposal put forward in this essay(s), 'How to read biblical texts in the 21st century', is certainly not a new invention. Rather, it is an expansion of biblical hermeneutics. In this regard, the essay will start by painting the environments within which hermeneutics were formulated and which definitely influenced the development of biblical hermeneutics. Then, a few recent publications on hermeneutical approaches will be analysed in order to propose an 'Integrated Approach to Meaning'4 (see Tate 2011) of texts in the 21st century. The current essay will then constitute the background and also create the environment within which a second, related essay5 has to be interpreted.

A brief history of hermeneutics6

It is not the objective of this study to explore the history of hermeneutics,7 but since there are new trends8 of development, it is relevant to provide a brief summary of the past century in order to have an overview of the history and development of hermeneutics. During the latter half of the 20th century, this field of research has become so vast and has branched out in so many different areas of specialisation that it has become virtually impossible to cover or evaluate the entire terrain.

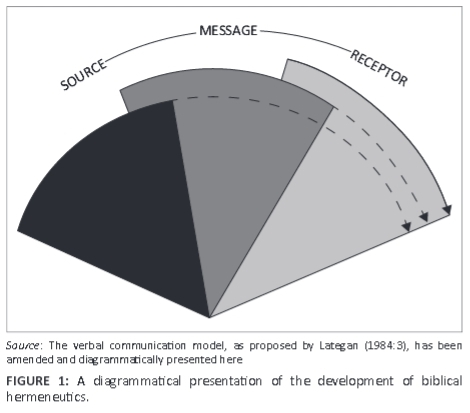

Three decades ago, Lategan (1984:1ff.) tried to find direction in the numerous currents and cross-currents in the field of theological hermeneutics to get an indication in which direction things were moving. In this exploration of the history and development of hermeneutics, I shall use and amend the model of Lategan (1984:3) as indicated in Figure 1.

Lategan uses the verbal-communication model to discuss the major shifts in the history of interpretation.9 In the phenomenon of verbal communication, there are at least three basic constituents in interplay: sender, message and receptor. Lategan (1984:2ff.) uses this model as a point of reference to locate and relate most of the issues that dominated the hermeneutical discussion up to the point of time when he conducted his research (also see Hartin & Petzer 1991:1; Longman 1987:13ff.; Tate 2011).10 The various sectors in this basic model indicate the history of the major shifts of interpretation. They represent three different groups of theories regarding the locus and actualisation of meaning: author-centred, text-centred and reader-centred approaches to the text (Lategan 1984:2ff.; Longman 1987:19ff.; Tate 2011:xvi).11

The source segment concerns the origins and text production. It focuses relentlessly on the world behind the text, the circumstances within which the text was born and the circumstances of the author. This segment refers to the historical period in hermeneutics dominated by the formidable historical-critical method.12

The message segment concerns text preservation and mediation and focuses on the world in the text. With the advent of inter alia New Criticism,13 the pendulum swung away from the historical-critical method. The first real paradigm shift, from diachronical to synchronical interests, occurred when structuralism14 emerged (Longman 1987:25ff.).15 The locus of meaning shifted to the autonomous text. The text itself became the focal point, and according to structuralism, meaning resides in the structure of the text (Du Toit 1974:56; Louw 1976:99f.; Mlakuzhyil 1987:17ff.; cf. Combrink 1983:8ff.; Snyman 1991:89). Only the text now legitimates an interpretation16 (Hartin & Petzer 1991:47ff.; Lategan 1984:1ff.; Longman 1987:25ff.).

At the end of the 20th century, another shift had taken place in the field of hermeneutics, namely a move towards the receptor sector of the diagram. This move consists of a variety of methods aimed at diverse objectives (Lategan 1984:4f).17 The focus is on the relationship between text and reader. It concerns the reception and interpretation of the text, and it focuses on the world in front of the text (cf. Lategan 1984:3).18

These many different approaches could easily be seen as competing methods and might consequently cause exegetes to lose their way in the inevitable relativism that ensues (Hartin & Petzer 1991:2). The opposite, rather, is true - each method has a particular function and purpose in illuminating the text.19 Some approaches are more suited to particular types of texts than others (cf. Deist & Burden 1983:128)20 or relate closer to certain questions being asked.

The crisis regarding the interpretation and understanding of the New Testament texts is caused largely by the lack of an integrated exegetical-hermeneutical approach (Lategan 1984:1ff.). If the exegete takes any of these approaches in isolation (author-centred, text-centred or reader-centred), excluding the other two, the exegetic-hermeneutical approach becomes an unbalanced discipline (Longman 1987:61; Tate 1991:210). The inescapable result of a one-mode approach will be the over21 or underexposure22 of texts as manifested especially during the historical, linguistic-literary and reader-response periods of methodology (Rousseau 1985:93). It was actually the appearance of the New Hermeneutic during the 1960s that opened the door for the succession of challenges for biblical studies during the latter part of the 20th century (Robbins 1996a:1).

Since literature is an act of communication between an author and a reader through a text (Longman 1987:6f.), hermeneutics calls for the integration23 of these three aspects of literature. They should not be abstracted from one another since one presupposes the other.24 No single method leads to a complete hermeneutical approach. The knowledge obtained by the different approaches is also needed.25 Hence, the locus of meaning is to be found in the interplay between all three worlds when they converge (cf. Van der Watt 1986:33). It is clear that all three areas are mutually inclusive in the articulation of meaning.

I shall now analyse some of the most recent publications on 'hermeneutics' and how they relate to the above reasoning.

Recent approaches to methodology

In this section, a few recent (new and updated) publications on the epistemology of biblical hermeneutics will be discussed. The motif behind this discussion is to view what the most recent approaches to 'biblical hermeneutics' have to offer and can contribute to the development of the understanding and employment of hermeneutics. This will also contribute to characterise a respectable and integrated approach to 'biblical hermeneutics in the 21st century'.

The first essay, Hays (2007),26 consists of three parts. In the first part of his essay, Hays (2007:5) argues that 'eyes of faith' should be the 'epistemological precondition' for reading the Bible as well as for the recovery of theological exegesis of the Bible. The second part (ibid:7-11) of the essay investigates contemporary arguments for non-theological exegesis with Räisänen, Fox and Meeks as components. The third part (ibid:11-15) argues in favour of theological exegesis and classifies theological exegesis not as a method but as a practice. Hays then identifies 12 characteristics of the practice of theological exegesis, which are the following:

• It is a practice of and for the church, and its pursuit is to read the Bible as normative for a community (ibid:11, 12).

• It '...is self-involving discourse ... it draws [the reader] into the world of the text and demands response ... Theological readings are closely linked with the practice of worship' (ibid:12).

• Historical study is part of it and a crucially important component for theological exegesis.

• It '... attends to the literary wholeness of the individual scriptural witness' (ibid:12).

• '[I]t always presses forward to the synthetic question of canonical coherence.' The big picture is always pursued, questioning how any particular text is part of the comprehensive biblical story of the gracious actions of God (ibid:13).

• It focusses on the texts as testimony about God (ibid:13).

• The theological exegesis is intratextual and remains close to the primary language (ibid:13).

• It draws itself into the complex web of the intertextuality of the Bible (2005:14).

• It is committed to discover and expose multiple senses in biblical texts due to the multiple layers in these texts (ibid:14).

• It regards itself as part of an ancient and lively conversation of the Christian tradition (ibid:14).

• It endeavours to produce fresh readings for the present through the Holy Spirit (ibid:15).

• Theological exegesis is a ministerium verbi divini [ministry of the divine word].

Virkler and Ayayo's ([1981] 2007) volume is introduced with a chapter on the 'History of biblical interpretation' (ibid:43-78). In the rest of the volume, Virkler and Ayayo outline a five-step hermeneutic procedure that includes the following: historical-cultural and contextual analysis (ibid:79-96); lexical-syntactical analysis (ibid:97-120) and theological analysis (ibid:21-146). Then they discuss special literary forms in the two categories on figures of style (ibid:147-166) and genre (ibid:167-192). In their final chapter, they concentrate on the application of the Bible message (ibid:193-216). They close with five appendices (ibid:229-240) of which at least one comprises a section on computer-based resources for exegetical studies (ibid:235-240). The goal of this book is not only to supply readers with interpretation principles but also to equip them to apply these discussed principles practically in sermon preparation and Bible studies.

The next article under discussion it that of Montague ([1991] 2007:v), who explains that this volume deals with the more restricted field of hermeneutics. Due to the fact that the Bible is in a class by itself (cf. Köstenberger 2012:9), the process of the interpretation of the Bible is not unlike the general process of hermeneutics.

Montague ([1991] 2007:vi) explains that this volume is an 'introduction', written for students. He tries to lead the students through the major stages and the principle theorists and practitioners of biblical hermeneutics. The first chapter begins with a biblical text which he uses as an example, noting the questions that will arise from the text when it is read. In the subsequent chapters, it becomes evident how even biblical authors themselves grapple with some of the questions. This occurs amongst all interpreters, from the postbiblical interpreters and theorists to those of our day. All of this is discussed in Part 1, which he refers to as 'The road already travelled' (ibid:9-126). In Part 2, entitled 'The road before us' (ibid:127-238), he organised the various hermeneutical methods used today (ibid:vii). The chapters in this part discuss 'The world of the text', 'The world behind the text', 'The world in front of the text' and 'The world around the text'. The 'Spiritual sense of scripture' and 'Dei Verbum: Text and commentary' also receive attention.

In his article, Osborne (2008:15) states that '...the purpose of this volume is to provide a comprehensive overview of the hermeneutical principles for reading any book, but in particular for studying and understanding the Bible ... to discover these precious biblical truths'. This extensive volume is comprised of three parts. Part 1 is about 'General hermeneutics' and covers aspects such as context, grammar, semantics, syntax, historical and cultural backgrounds (ibid:35-180). Part 2 is about 'Genre analysis' and discusses aspects such as Old Testament law, narrative, poetry, wisdom, prophecy, apocalyptic, parable, epistle writings and the Old Testament in the New Testament (ibid:181-344). Part 3 is all about 'Applied hermeneutics' (ibid:345-464). This part discusses biblical theology, systematic theology, homiletics 1: contextualisation and homiletics 2: the sermon. The volume closes with two appendixes:

1. The problem of meaning: The issues (ibid:465-499).

2. The problem of meaning: Toward a solution (ibid:500-512).

Tate (2011), the next author in the list of current approaches to hermeneutics, states categorically that his book is not a textbook on critical methodologies but rather an introduction to doing hermeneutics. He does not adopt a single-method approach. In order to inform the reader of hermeneutics, he communicates the options that the individual methods offer. Tate's objective is threefold: He (ibid) offers his readers the following:

... the synopses here [aim] to (a) introduce readers to the many doors of access that the methods present, (b) encourage interest in the methods and their potential roles in understanding texts more fully, and (c) assist the reader in recognising the scope of biblical hermeneutics. (2011:n.p.)

In the introductory chapter, Tate orientates the reader about the three worlds27 that are applicable in the reading of ancient texts and concludes with the integration of these three approaches in the hermeneutical process. These four aspects constitute the structure of the book. The last part of the book comprises four appendices in which he discusses methods that focus on the four opted scenarios.28 Tate does not merge all three worlds simultaneously. For him, the best is a marriage between two worlds: either between the worlds of the reader and the text or between the worlds of the author and the text.

Next in line is Deppe (2011), who advocates eight methods of inquiry in biblical exegesis. These include literary analysis, grammatical analysis, structural analysis, context analysis, cultural and historical investigation, history of interpretation, theological exegesis and the personalising of the text. Instead of a philosophical and theoretical grounding for each of these methodologies, Deppe concentrates on examples (case studies on various biblical passages) to enlighten the biblical texts and to investigate the value of each method. After each chapter, he includes a list of practical and text-based questions for further enquiry and application. This practical approach distinguishes his approach from others on the subject of hermeneutics and biblical methodology. The case studies of various biblical passages intend to demonstrate the value of each road of investigation (ibid:xiii). Due to the fact that computer-generated exegesis is currently an important medium of studying the Bible, exegetical examples demonstrate the use of Logos Bible Software.

The volume of Porter and Robinson (2011) is not an inclusive survey of hermeneutics and runs the risk of moving too quickly over complex issues and ideas. It is also not a specialised volume on a single topic. It is actually a volume that offers a critical analysis of the major movements and persons in hermeneutics and interpretive theory during the modern era in particular as these movements and interpreters influenced and impacted biblical and theological studies. The selected and conferred movements and persons are: hermeneutics and new foundations (Schleiermacher and Dilthey), phenomenology and existential hermeneutics (Husserl and Heidegger), Gadamer's philosophical hermeneutics, Ricoeur's hermeneutic phenomenology, Habermas's critical hermeneutics, Patte and structuralism, Derrida and deconstruction, dialectical theology and exegesis (Barth and Bultmann), theological hermeneutics (Thiselton and Vanhoozer) and, finally, literary hermeneutics (Culpepper and Moore).

Köstenberger (2012), whose work is the next point of interest, points out the following:

[The] foundational hermeneutical principle which needs to be periodically re-examined and reaffirmed is that the proper goal of interpretation is to discern a given author's intent in writing to his or her original audience. (p. 4)29

Köstenberger (2012:3-12), with his 'hermeneutical triad', makes a valuable and useful contribution to 'biblical hermeneutics'. In his introductory paragraphs, he explains that the hermeneutical triad consists of 'history, literature, and theology' realities (ibid:3). These are three inescapable realities which the interpreters of Scripture face. The history reality points out that the revelation of God to humanity took place in a real-life, time-and-space continuum. The literature reality refers to the texts that contain revelation and that require interpretation (ibid:5). The theology reality refers to the reality of God and his revelation in Scripture (ibid:6).

For Köstenberger, choosing this trifocal lens is critical for maintaining any balance in the hermeneutical endeavours. He points out that the history of interpretation is filled with examples of interpreters who unilaterally emphasised one or two elements of the triad whilst neglecting the other. For example, some exegetes work with the historical-critical method only and others work with the text-immanent method only (Köstenberger 2012:7). The proper interpretation of biblical texts can only be achieved through the author's communicative intent. The trifocal lens responsible for sharper focus is the hermeneutical triad of history, literature and theology (ibid:8). For Köstenberger (ibid:9) the Bible is not just like any other book, but it is rather, for him, '...the inerrant, inspired Word of God'.

Köstenberger (2012) makes the following claim about his work:

[Due to a] solid foundation of an authorial-intent hermeneutics, and equipped with the new, finely tuned trifocal lenses of the 'hermeneutical triad,' the method we propose in our hermeneutics text, then, looks like this. (p. 10)

Köstenberger, then distinguishes three steps in this interpretative task: a (spiritual) preparation phase, an interpretation phase and an application and proclamation phase (ibid:10).

The last hermeneutical approach to be discussed is the socio-rhetorical approach to the interpretation of biblical texts by Vernon Robbins (1996a, 1996b; 2010). He states the following (Robbins 2004):

Socio-rhetorical interpretation is a multi-dimensional approach to texts guided by a multi-dimensional hermeneutic. Rather than being one more method for interpreting texts, socio-rhetorical interpretation is an interpretive analytic - an approach that evaluates and reorients its strategies as it engages in multi-faceted dialogue with the texts and other phenomena that come within its purview. This means that it invites methods and methodological results into the environment of its activities, but those methods and results are always under scrutiny. Using insights from sociolinguistics, semiotics, rhetoric, ethnography, literary studies, social sciences, and ideological studies, socio-rhetorical interpretation enacts an interactive interpretive analytic that juxtaposes and interrelates phenomena by drawing and redrawing boundaries of analysis and interpretation. (p. 1)30

Gowler (2010:191; cf. also Robbins 1996a:11-13) adds that this approach provides a powerful and comprehensive interpretive analytic in exploring the dialogical interrelations between the author, text and reader or interpreter. Robbins introduced this terminology into New Testament studies in 1984.31 It has also, since the publication of the two 'textbooks',32 undergone a vast development and actually became a science in its own right. On all continents, there are scholars who have committed themselves to this methodology. Many publications and developments of this approach have followed since 1996. Currently this approach is probably the most successful one due to a large number of scholars who have been using it on a number of texts and contexts33 and consequently contributed to the development of socio-rhetorical criticism. In the Festschrift for Robbins, Kloppenborg (2003) wrote the following:

... Robbins had the clarity of mind to see how to integrate these diverse methods and approaches to the texts of antiquity into a multi-dimensional method which identifies various registers or 'textures' in an effort to understand how a text works on the intellect, emotions, and sensibilities of its readers and hearers and how the worlds of the readers or hearers variously affect the appropriation of the text. (p. 64)

In the 'Introduction' to the Blackwell companion of the New Testament, Aune (2010:4) refers to socio-rhetorical criticism as '... a holistic combination of methods and approaches to reading and interpreting texts that Robbins describes as an "interpretive analytic", namely "a multidimensional approach to texts guided by a multi-dimensional hermeneutic"'.

During the 1990s, socio-rhetorical criticism became more idiosyncratic when Robbins began with delineating these textures of texts in 1992. This process reached a definite form in 1996 when Robbins published the two textbooks in which he defines and explains these textures (Robbins 1996a, 1996b; also Gowler 2010:195ff.).34

Inner texture

Robbins (1996b:7) describes the inner texture as the process to get inside the text. This texture resides in the linguistic features like repetition of words and the use of dialogue between two characters who communicate information. In other words, the inner texture is the written text itself. The purpose of this analysis is the gaining of intimate knowledge of word, word patterns, voices structures, devices and modes in the text. This texture focusses on the linguistic patterns within texts, the structural elements in texts and the particular mechanisms, also in texts, which the author uses to persuade the readers. Robbins (1996b:9) uses tables to execute this process. Differing from Robbins, I make use of discourse analysis which is, according to my opinion, more effective especially in the creation of semantic networks in the text and in determining the rhetoric of the author.

Inter-texture

This texture pays attention to references in the text, which refer to phenomena in the 'world' outside of the text as well as phenomena outside of the text that have been used in the text. This can include text citations, allusions and the reconfigurations of particular texts, events, objects and institutions as well as the interaction with any extra-textual contexts (Robbins 1996b:40).

Social and cultural texture

This texture refers to the interaction of the text with society and culture. It is evident from the text's sharing in social and cultural attitudes, and norms and modes of interaction generally known in the society (Robbins 1996b:71). The texture also interacts by connecting itself to the dominant cultural system by either rejecting, sharing or transforming the attitudes, values and dispositions of the system (Gowler 2010:195).

Ideological texture

This texture concerns those specific alliances and conflicts evoked and nurtured by the text, the interpretation of the text as well as the way in which interpreters of the text position themselves in relationship to other characters and groups referred to in the text. Readers should also identify and interpret the ideological point(s) of view that emerge from the text as well as their own subjective ideological point(s) of view (Gowler 2010:195; also Robbins 1996b:95).35

Sacred texture

This texture denotes the insights which the text communicates concerning the relationship between the divine and human beings. It guides the reader to search in a programmatic way for sacred aspects of a text. The texture includes characters such as deity, holy persons, spirit being and aspects such as divine history, human redemption, religious community and ethics (see Gowler 2010:195). Incorporated here should also be the various theological structures and profiles to be found in the various books in the Bible (Gowler 2010:195; Robbins 1996b:120ff.).

According to the brief description above, the socio-rhetorical interpretation of texts is a '... multi-dimensional approach to texts guided by a multi-dimensional hermeneutic ... an interpretive analytic' (Robbins 2004:1, 2). It takes for granted the following (Gowler 2010):

... texts are always in dialogical relationship with their contexts, a relationship which incorporates, in different ways, the words of others that precede them, and, also in different ways, the texts and voices that respond to them. (p. 203)

This implies that the meaning of any text resides not solely in the creativity of the author but that complex correlations also exist between texts and the contexts in which these texts have been read and reread. Such correlations include specific relationships between the creator of the text and those who contemplate the text. This infers that all texts and all communications are intertextual. In this regard, the socio-rhetorical interpretation of Robbins provides a powerful analytical interpretation to explore dialogical interrelations amongst authors, texts and readers (Gowler 2010:203).36

Conclusion

According to this investigation, it is evident that the one-dimensional approach of reading and interpreting biblical texts made space for a multi-dimensional approach. Seven of the nine discussed publications, namely Hays (2007), Deppe (2011), Köstenberger (2012), Montague ([1991] 2007), Robbins (1996b, 2010), Tate (2011) and Virkler & Ayayo ([1981] 2007), opt for an integrated hermeneutical approach. According to these approaches, the single-method approaches in the hermeneutical process have to be replaced with an integrative approach. This seems to be the hermeneutical direction for the 21st century.

From the brief descriptions of these approaches, the hermeneutical approach of Vernon Robbins seems to have been viewed as an comprehensive and multi-dimensional approach for some years now.37 It serves not only as a taxonomy of the various other approaches38 but is outstanding and recommendable due to its integrated, advanced analytical character, coherency, praxis39, clear epistemology of what socio-rhetorical criticism comprises and it continuous dynamic academic development. The other hermeneutical approaches that have been briefly referred to are also invaluable. Each one has its own distinctiveness, approach, emphasis and vantage points and can be used complementary to the integrated and coherent socio-rhetorical approach of Robbins.

Interpretation should never stop at only the academic explication or even the ecclesiological application of the biblical text. Interpretation (hermeneutical process) culminates when the embodiment of analysed texts has taken place in the lives of believers and the Christian principles embedded in texts become a way of life. The embodiment of texts can be assisted when 'lived experiences' ensue in the contemplative reading of biblical texts. Interpretation must become an explication which must consequently become application in order to culminate in the embodiment of the text to result in a way of life.40 The spiritualities (lived experiences) generated by intersecting with the text should function as catalysts for the embodiment of texts in the hermeneutical process.

A succeeding essay, Reading the Bible in the 21st century: Some hermeneutical principles (Part 2), will investigate how the 'embodiment' and 'spirituality' of biblical texts can be incorporated and be applied in the hermeneutic process.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Aune, D.E., 2010, The Blackwell companion of the New Testament, Blackwell Publishing, West Sussex. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781444318937 [ Links ]

Barr, J., 1973, 'Reading the Bible as literature', Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library 56, 10-33. [ Links ]

Combrink, H.J.B., 1983, 'Die pendulum swaai terug: Enkele opmerkings oor metodes van Skrifinterpretasie', Skrif en Kerk 4(2), 3-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v4i2.914 [ Links ]

Craig, W.L., n.d., Presuppositions and pretentions of the Jesus Seminar, viewed 03 March 2015, from http://www.leaderu.com/offices/billcraig/docs/rediscover1.html [ Links ]

Culpepper, R.A., 1983, Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel, Fortress, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Deist, F.E. & Burden, J.J., 1983, An ABC of biblical exegesis, Van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Deppe, D., 2011, All roads lead to the text: Eight methods of inquiry into the Bible, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, I.J., 1988, 'Reading Luke 12:35-48 as part of the travel narrative', Neotestamentica 22(2), 217-234. [ Links ]

Du Rand, J.A., 1990, 'Narratological perspectives on John 13:1-38', Hervormde Teologiese Studies 46, 367-389. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v46i3.2325 [ Links ]

Du Toit, A.B., 1974, 'The significance of discourse analysis for New Testament interpretations: Introductory remarks with special reference to I Peter 1:3-13', Neotestamentica 8, 54-79. [ Links ]

Frör, K., 1964, Biblische Hermeneutik; zur Schriftauslegung in Predigt und Unterricht, Kaiser, Munchen. [ Links ]

Goodwin, D., 1993, 'Rhetorical criticism', in R. Makaryk (ed.), Encyclopedia of contemporary literary theory, pp. 174-178, University of Toronto Press, Toronto. [ Links ]

Gowler, D.B., 2010, 'Socio-rhetorical interpretation: Textures of a text and its reception', Journal for the study of the New Testament 33(2), 191-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0142064X10385857 [ Links ]

Green, J.B., 2011, 'Rethinking "history" for theological interpretation', Journal of Theological Interpretation 5(2), 159-174. [ Links ]

Halliday, M.A.K., 1978, Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning, Edward Arnold, London. [ Links ]

Halliday, M.A.K. & Hasan, R., 1989, Language, context and text: Aspects of language in a social-semantic perspective, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Hartin, P.J. & Petzer, J.H., 1991, Text and interpretation: New approaches in the criticism of the New Testament, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Hays, R.B., 2007, 'Reading the Bible with eyes of faith: The practice of theological exegesis', Journal of Theological Interpretation 1, 5-21. [ Links ]

Historical Jesus theories, n.d., Early Christian writings, viewed 25 February 2014, from http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/jesus/robertfunk.html [ Links ]

Jeanrond, W.G., 1991, Theological hermeneutics: Development and significance, Crossroad, New York. [ Links ]

Kloppenborg, J.S., 2003, 'Ideological texture in the parable of the tenants', in V.K. Robbins, D.B Gowler, L.G. Bloomquist & D.F. Watson (eds.), Fabrics of discourse: Essays in honor of Vernon K. Robbins, pp. 64-88, Trinity Press International, Valley Forge. [ Links ]

Köstenberger, A.J., 2011, Invitation to biblical interpretation: Exploring the hermeneutical triad of history, literature, and theology, Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Köstenberger, A.J., 2012, 'Invitation to biblical interpretation and the hermeneutical triad: New hermeneutical lenses for a new generation of bible interpreters', Criswell Theological Review 10(1), 3-12. [ Links ]

Kümmel, W.G., 1973, The New Testament: The history of the investigation of its problems, S.C.M. Press, London. [ Links ]

Lategan, B.C., 1984, 'Current issues in the hermeneutic debate', Neotestamentica 18, 1-17. [ Links ]

Longman, T., 1987, Literary approaches to biblical interpretation, Academy Books, Michigan. [ Links ]

Louw, J.P., 1976, Semantiek van Nuwe Testamentiese Grieks, Universiteit van Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

McKin, D.K. (ed.), 1986, A guide to contemporary hermeneutics: Major trends in biblical interpretation, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Mickelsen, A.B., 1970, Interpreting the Bible, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Mlakuzhyil, S.J., 1987, The Christocentric literary structure of the Fourth Gospel, Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico, Roma. [ Links ]

Montague, G.T., [1991] 2007, Understanding the Bible. A Basic introduction to biblical Interpretation, Paulist Press, Mahwah. [ Links ]

Nida, E.A. & Louw, J.P., 1983, Style and discourse, N.B.P., Cape. [ Links ]

Oeming, M., 2006, Contemporary biblical hermeneutics: An introduction, transl. F.V. Joachim, Ashgate, Burlington. [ Links ]

Osborne, G.R., 2008, The hermeneutical spiral. A comprehensive introduction to biblical interpretation, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove. [ Links ]

Poirier, J.C., 2009, '"Theological interpretation" and its contradictions', Tyndale Bulletin 60(2), 105-118. [ Links ]

Porter, S.E. & Robinson, J.C., 2011, Hermeneutics. An introduction to interpretive theory, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Poythress, V.S., 1978, 'Structuralism and biblical studies', Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 21, 221-237. [ Links ]

Poythress, V.S., 1980, 'Review of Two Horizons', Westminster Theological Journal 43(1), 178-180. [ Links ]

Poythress, V.S., 1993, 'Review of New Horizons', Westminster Theological Journal 55(1), 343-346. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P., 1975, 'The task of hermeneutics', in F. Bovon & G. Rouiller (eds.), Exegesis: Problems of method and exercises in reading (Genesis 22 and Luke), pp. 1-15, Pickwick, Pittsburg. [ Links ]

Robbins, V.K., 1996a, The tapestry of early Christian discourse: Rhetoric, society and ideology, Routledge, London. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203438121 [ Links ]

Robbins, V.K., 1996b, Exploring the texture of texts: A guide to socio-rhetorical interpretation, Trinity Press International, Valley Forge. [ Links ]

Robbins, V.K., 2004, Beginnings and developments in socio-rhetorical interpretation, Emory University, Atlanta. [ Links ]

Robbins, V.K., 2010, 'Socio-rhetorical interpretation', in D.E. Aune (ed.), The Blackwell companion to the New Testament, pp. 192-219, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781444318937.ch13 [ Links ]

Robbins, V.K., n.d., Socio-rhetorical interpretation, bibliography of socio-rhetorical interpretation, viewed 18 February 2014, from http://www.religion.emory.edu/faculty/robbins/SRI/defns/bib.cfm [ Links ]

Rossouw, H.W., 1980, Wetenskap, interpretasie, wysheid, Universiteit van Port Elizabeth, Port Elizabeth. [UPE-publikasiereeks B7] [ Links ]

Rousseau, J., 1985, 'The communication of ancient canonised texts', Neotestamentica 19, 92-101. [ Links ]

Scheffler, E., 1988, 'A psychological reading of Luke 12:35-18', Neotestamentica 22, 355-372. [ Links ]

Smit, D.J., 1988, 'Responsible hermeneutics: A systematic theologian's response to the readings and readers of Luke 12:35-48', Neotestamentica 22, 441-484. [ Links ]

Snyman, A.H., 1991, 'A semantic discourse analysis of the letter of Philemon', in P.J. Hartin & J.H. Petzer (eds.), Text & interpretation: New approaches in the criticism of the New Testament, pp. 83-100, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Tate, W.R., 2011, Biblical interpretation: An integrated approach, Baker, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Theissen, G., 1978, Sociology of early Palestinian Christianity, Fortress Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Thiselton, A.C., 1980, The two horizons: New Testament hermeneutics and philosophical description with special reference to Heidegger, Bultmann, Gadamer, and Wittgenstein, Paternoster Press, Carlisle. [ Links ]

Thiselton, A.C., 1992, New horizons in hermeneutics, Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Thiselton, A.C., 2009, Hermeneutics: An introduction, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Van Aarde, A.G., 1988, 'Historical criticism and holism: Heading towards a new Paradigm?', in J. Mouton (ed.), Paradigms and progress in theology, pp. 49-64, HSRC, Pretoria. [HSRC Studies in Research Methodology] [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J.G., 1986, 'Ewige lewe in die evangelie volgens Johannes, vol. I', DD-proefskrif, Departement, Universiteit van Pretoria. [ Links ]

Van Eck, E., 2001a, 'Socio-rhetorical interpretation: Theoretical points of departure', Hervormde Teologiese Studies 57(1/2), 593-611. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v57i1/2.1884 [ Links ]

Van Eck, E., 2001b, 'Socio-rhetorical interpretation in practice: Recent contributions in perspective', Hervormde Teologiese Studies 57(3/4), 1229-1253. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v57i3/4.1887 [ Links ]

Van Tilborg, S., 1989, 'The Gospel of John: Communicative processes in a narrative text', Neotestamentica 23(1), 19-31. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, H.C., 1982, 'Structural analysis of Matthew 18', Neotestamentica 16, 35-55. [ Links ]

Virkler, H.A. & Ayayo, K.G., [1981] 2007, Hermeneutics. Principles and processes of biblical interpretation, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Vorster, W.S., 1991, 'Through the eyes of a historian', in P.J. Hartin & J.H. Petzer (eds.), Text and interpretation: New approaches in the criticism of the New Testament, pp. 15-46, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dirk van der Merwe

189 Kotie Avenue

Murrayfield 0184

South Africa

Email: vdmerdg@unisa.ac.za

Received: 20 Oct. 2014

Accepted: 31 Mar. 2015

Published: 22 June 2015

Note: This article is the first of a two part series based on a paper delivered at the Pan African New Testament Congress on 06-07 March 2014 at the University of Pretoria.

1. For a few recent publications, see Deppe (2011); Hays (2007); Köstenberger (2012); Montague ([1991] 2007); Osborne (2008); Robbins (1996b); Tate (2011) and Virkler and Ayayo ([1981] 2007). Also see the three major publications by Thiselton (1980, 1992, 2009).

2. See the excellent contribution of Porter and Robinson (2011) on hermeneutics. They have a generic approach in which they discuss six distinct hermeneutical trends: romantic, phenomenological and existential, philosophical, critical, structural, and post-structural (deconstruction).

3. See footnotes 9, 13-16.

4. Author-centered approaches to meaning tend to neglect the world of the text and the world of the reader. Text-centered approaches, in claiming textual autonomy, downplay the boundaries imposed by the world of the author upon the text ... reader-centered approaches generally find meaning in the interaction between the worlds of the text and the reader' (Tate 2011).

5. The second and related essay, 'Reading the bible in the 21st century: Some hermeneutical principles (Part 2)', will (1) investigate the evoking of spiritualities (lived experiences) in the reading of biblical texts which should be regarded as an addition to biblical hermeneutics and (2) the embodiment of texts as the culmination and completion of the hermeneutical spiral.

6. In this first section, I was influenced by the chapter on 'hermeneutics and methodology' in my thesis, 'Discipleship in the Fourth Gospel', which I have amended for use here.

7. It is worth mentioning the name of Anthony Thiselton for his major contributions on hermeneutics in terms of providing an all-inclusive picture of hermeneutics in his three mammoth publications. In The two horizons, he analyses the contributions of philosophical hermeneutics to New Testament studies. In it, he deals extensively with the writings of the earlier and later Heidegger, Bultmann, Gadamer, the new hermeneutic and the earlier and later Wittgenstein (Poythress 1980:178-180). Another major work of even greater significance was his New horizons in hermeneutics. The latter volume tends to be an advanced textbook in hermeneutics. It undertakes the epic task of including a description and critical evaluation of all the major theoretical models and approaches which characterise current hermeneutical theory, or which have contributed to its present shape' (Thiselton 1992:1). Due to his interest in how hermeneutical theories may apply to biblical interpretation, the title has the subtitle 'The theory and practice of transforming biblical reading' (Poythress 1993:343-346). In his third volume, Hermeneutics: An introduction, Thiselton follows a historical trajectory. From the basic conception of hermeneutics, he examines interpretive methods from the ancient world through postcolonial hermeneutics to American postmodern perspectives on the discipline. With this volume Thiselton (2009) provides a comprehensive and unmatched introduction to the genre of hermeneutics. For more reviews of the history of theological hermeneutics see Deppe (2011:194227), Frör (1964), Jeanrond (1991:12-76), Longman (1987:13-46), Mickelsen (1970: 20-53) and Virkler and Ayayo ([1981] 2007:43-78). For a very thorough analysis of the history of biblical hermeneutics, see the classic work of Kümmel (1973).

8. See the second section in this essay, entitled 'Recent approaches to methodology'.

9. According to Rossouw (1980:17-55), hermeneutics originated from a reading situation where dealing with texts was the order of the day. Rules were necessary to guide exegetes in readings. Towards the end of the 18th century, the issue was broadened to also include the conditions that make possible understanding. A further widening of horizons was introduced by Schleiermacher, Dilthey and Heidegger (cf. Lategan 1984:2; Ricoeur 1975:268ff.).

10. What definitely changed during the past few decades is the emerging of a pluralistic hermeneutical approach in Biblical exegesis (in the sense that all three basic constituents of the communicational process are incorporated) in contrast to a (previous) singular approach. This phenomenon will be discussed in the part on recent approaches to methodology.

11. Porter and Robinson (2011:4) point out that, even today, an ongoing debate rages in hermeneutics concerning which elements are to be emphasised in the tripartite relationship of author, text and reader for the purpose of bridging the gaps in understanding. Should it be between (1) the authors and their intentions placed within the text, (2) the texts and the cultural-historical context of the text or (3) the present situations of the readers and socio-historically way of understanding the text. See also the work of Hays (2007:5-21).

12. All the different variations such as textual criticism, source criticism, form criticism, tradition criticism and redaction criticism are grouped under the historical-critical method. See also Tate (2011).

13. According to Longman (1987:25f.), 'New Criticism describes a general trend in literary theory that dominated thinking in the 1940s and 1950s.' With regard to the primary principle of New Criticism, he (Longman 1987:25f.) states that the literary work is self-sufficient; the author's intention and background are unimportant to the critic'.

14. Structuralism describes a broad movement that affects many disciplines. Poythress (1978:221) maintains that structuralism is more a diverse collection of methods, paradigms and personal preferences than it is a "system", a theory or a well formulated thesis'. Longman (1987:29) points out that the emergence of structuralism as a major school of literary criticism only began in the 1960s.

15. It must be noted (also noticed from the diagram) that, even though a paradigm shift has taken place, the historic-critical approach did not cease to exist (Hartin& Petzer 1991:3; Vorster 1991:15; cf. Van Zyl 1982:35), but the emphasis has shifted to the new literary-linguistic approach. The same also happened when the

emphasis was moved to an approach that focused on the receptor.

16. Longman (1987:25) indicates two major schools of thought in this period, namely, New Criticism and Structuralism. Hartin and Petzer (1991:47ff.) point out the following trends: semiotics, discourse analysis, narrative criticism and speech-act theory (and textual criticism).

17. Actually, a number of shifts took place. Firstly, in this new era, there was a shift towards pragmatism and contextual interpretation. This new trend was ‘… more interested in the effect of communication than in its mechanics’ (Lategan 1984:4; see also Van der Merwe 1996:49. This stemmed from an attitude that the results of traditional exegesis had very little relevance to the needs of the day (Lategan 1984:4). Secondly, socio-linguistics (cf. Nida 1984:2 quoted by Lategan) became important for theological hermeneutics. This entailed a renewed interest in the setting of text and the reader and arose from the problems of biblical translation in transcultural settings. According to Theissen (1978:3), the sociological approach formed part of the historical method and was in fact the logical outcome of the historical-critical exegesis of the New Testament. Thirdly, ‘reception theory’ became an important trend in theological hermeneutics. It arose from a reader-oriented approach and gained momentum during the last four decades. Reception theory derives from Russian Formalism, the Prague Structuralists and the sociology of literature (Lategan 1984:4ff.). Longman (1987:38) and Hartin and Petzer (1991:145ff.; also see McKin 1986:241ff.) add three types of ideological readers: liberation theologians, Marxists and feminists. Other trends which form part of this section of interpretation are Reception Theory, Rhetorical Criticism, Deconstruction, Fundamentalism and Sociological-cultural and Contextual methodological principles. Scheffler (1988:355ff.) attempted psychological exegesis. Cf. Thiselton (1992:10ff.) for additional perspectives on ‘New horizons in

the development of hermeneutics’.

18. The shift to the right-hand sector of the diagram (the reader-orientated context) does not eliminate the problems related to the historical and structural contexts. However, if they are combined, we might discover a better-defined methodology to come to a better understanding of the text.

19. No method comprises the whole process of interpretation. In fact, each method provides useful information if it can be viewed as a partial method only, answering specific questions (Smit 1988:442).

20. Hartin and Petzer (1991:2) use the image of a flashlight to explain this dilemma. According to them, just ‘… as a flashlight illuminates a certain segment of reality, so a stronger flashlight will illuminate a wider segment; or if the flashlight is shifted to focus attention on a different part of reality, so different aspects are revealed. The same is true of the various methods. Like the flashlight, they illuminate the text with which they are dealing in different ways. The text that is illuminated reveals different aspects of its beauty, depending upon the methods that are used’. Thus each method has value, and some are simply more appropriate to a particular field.

21. This concerns the over-emphasising of a certain mode which can in the end distort the communication process (cf. Barr 1973:13). Historical over-exposure breaks up the New Testament text or degrades it to the status of a historical book (Rousseau 1985:93). In the case of the linguistic-literary aspect, the structure of the text is over-emphasised, sometimes at the expense of its message, to claim textual autonomy.

22. The underexposure of texts implies ignoring the ‘… true nature, the message and intention of the NT’ (Rousseau 1985:93). To underexpose the historical approach means to ignore the historical background of the text and author. To underexpose the linguistic-literary mode means to ignore literary and stylistic features.

23. The following scholars move in the direction of a more comprehensive methodological approach in the sense of communicational dynamics: Deppe (2011), (Hays (2007), Köstenberger (2012), Lategan (1984:1ff.), Montague ([1991] 2007), Nida and Louw (1983:145ff.), Robbins (1996b), Rousseau (1985:92ff.), Tate (2011), Van Tilborg (1989:63ff.), Virkler and Ayayo ([1981] 2007). C f. also Culpepper 1983:4ff., Du Rand 1990:8ff., Longman 1987:19ff., Van Aarde 1988:235ff. Culpepper and Du Rand incorporate all the basic constituents from a narratological approach. In Neotestamentica 22 (1988), almost all the contributions, whether explicitly (Botha, Hartin, Scheffler, Van Aarde, Van Rensburg, Van Staden) or implicitly expressed (I.J. du Plessis, J.G. du Plessis, Sebothoma, Schnell), underscore the fact that all the methods applied here need additional information and therefore also complimentary methods (Smit 1988:451).

24. Scheffler (1988:369) investigates the relationship between psychological exegesis and other approaches. He emphasises that, ‘… although different models will in some respects surely be contradictory, they definitely seem to complement one another in many other respects’. With this point of view, Scheffler indicates the complementary nature of methods. In his essay ‘Reading Luke 12:35–48 as part of the travel narrative’, Du Plessis (1988:217–234) seems to make use of a combination of approaches, including form criticism, redaction criticism, structural analysis and a study of rhetorical devices. Smit (1988:459), on his part, is unoptimistic about a comprehensive approach in methodology. In his opinion, responsible hermeneutics need not be a comprehensive approach which includes various methods, focusing on the history of the text, the text itself and the readers of the text. Smit (1988:460f.) correctly states that ‘… reading strategies, or methods of interpretation, can never be seen as more or less legitimate in themselves, in a time and abstract way, but only in terms of a specific reader on a specific occasion’, in other words, from a ‘specific context’. Smit’s criticism of a comprehensive approach should be viewed from his systematic-theological background which is theological-philosophically oriented.

25. The world of the author offers foundational information for the dialogue between the reader and the text. Whilst background studies of the world behind the text do not constitute sufficient meaning within themselves, such studies do fulfil an important heuristic function within the field of hermeneutics. Every text thus reflects the ‘culture’ from which it was written, including biblical texts. According to Halliday (1978) and Halliday and Hasan (1989), language is part of the social system. This influences the way in which the text itself speaks linguistically, conventionally and ideologically. Historical methods should be used to perpetuate the dialogue between the text and the reader (Van Aarde 1988:236f.). They should inform the dialogue between text and reader (cf. Tate [1991] 2011:210; Lategan 1984:4). One must therefore adopt the viewpoint that the linguistic-literary perspective is embedded in a socio-historical situation. The ability to construct the socio-historical background from a reading of the text stems from sensitivity to the requirements and indications found in it (cf. Van der Watt 1986:38; Lategan 1984:8).

26 .See also the publication of Poirier (2009:105-118), who tries to defend and legitimise the use of 'theological interpretation' which Hays tries to explain in his article. Green (2011:159-174), who probably finds himself in the same academic environment as Hays and Poirier, also tries to defend the legitimacy of this hermeneutical approach by relating it to 'historical' investigation to form part of this hermeneutical process.

27. (1) The world behind the text (author-centred approach), (2) the world in the text (text-centred approach) and (3) the world in front to the text (reader-centred approach).

28. Author-centred: form criticism, genetic criticism, tradition criticism. Text-centred: formal criticism, rhetorical criticism, speech-act theory, structuralism. Reader-centred: African-American criticism, cultural criticism, deconstruction, new historicism, postcolonial criticism and liberation theology, reception theory, womanist criticism or theology. Methods that involve more than one world are the following: ideological criticism, Marxist criticism, mimetic criticism, narrative criticism, socio-rhetorical criticism.

29. This view is paradoxical to the view later proposed by me.

30. Critique on the method of Robbins argues that this methodology is indeed not socio-rhetorical but rather historical-critical. How then does one explain the position or function of the inner-texture, inter-texture (text-immanent), ideological texture and sacred-texture?

31. See the publication of Robbins (2004:1-44) in which he describes the beginnings and developments of socio-rhetorical interpretation.

32. Robbins published two programmatic books during 1996, The tapestry of early Christian discourse and Exploring the texture of texts: A guide to socio-rhetorical interpretations.

33. One can see this from the internet site 'Bibliography of socio-rhetorical interpretation', compiled by Robbins (n.d.). Due to the scientific development and academic interest in this approach, it will be discussed in more detail than the others. See also the huge number of publications on socio-rhetorical criticism by Robbins himself (2004:20-26).

34 .Rhetorical criticism is concerned with the social nature of reality, in particular the interrelationship between language and human action. It is also concerned with how language attempts to create effects on audiences. Rhetorical criticism focusses on theories and methodologies that can explain and evaluate the motivations and exhortations of speakers (writers), the responses of audiences (readers), the structures of discourse as well as any form of development within environments of communication (Goodwin 1993:177; cf. also Gowler 2010:194).

35. Robbins (2004:44) is correct with his statement that socio-rhetorical interpreters continue to face major challenges in analysing and interpreting texts. This has resulted in the challenge to write programmatic commentaries that displays the manifold ways in which early Christian writings blend early Christian rhetorolects together'.

36. Socio-rhetorical criticism has established itself as one of the promising new and dynamic methods of studying the Bible today. Robbins provides a practical primer to socio-rhetorical criticism. He illustrates the method by guiding the reader through investigating specific texts and narratives in the New Testament. This opens the way for new lived experiences and the embodiment of the text (see Gowler 2010:203). Cognisance has also to be taken of the social-scientific approach that is closely related, in my opinion, to this socio-rhetorical approach of Robbins. See a discussion of this methodology as well as its application in the two articles of Van Eck (2001a, 2001b), although he endeavours to point out the differences.

37. Unless someone wants to work with only one specific aspect of the hermeneutical process.

38. A problem emerges when scholars absolutize an individual methodology with which they work. Then they want to use that as a lens through which they look and interpret every text, even every phenomenon, e.g. those who work socio-culturally. In such an absolutized approach, religion, deities, et cetera suddenly all have socio-cultural origins. It then becomes a fallacy.

39. Robbins also shows or explains how the various textures can be applied. It is not only a matter of 'what' should be done but also 'how' it should be done.

40. Köstenberger and Deppe are the only two to refer explicitly to 'application' or 'personalising' of the text.