Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Verbum et Ecclesia

versão On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versão impressa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.36 no.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/VE.V36I1.1334

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Christian Leadership as a trans-disciplinary field of study

Volker KesslerI, II; Louise KretzschmarII

IAkademie für christliche Führungskräfte, Germany

IIDepartment of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The focus of this article is on Christian Leadership as a theological and academic field of study, rather than on the praxis of Christian leadership. We define Christian Leadership and note the varying ecclesial, theological and social contexts within which research in the field of Christian Leadership is conducted. We discuss some trends and areas of interest that emerge from within African and European contexts, especially those of South Africa and Germany. In the article, we show how research in Christian Leadership is linked to other disciplines, both theological and non-theological. Finally, we identify key areas of research and methodological issues relevant to the field of Christian Leadership, particularly in relation to the disciplines of Practical Theology and Theological Ethics. We give special credit to Schleiermacher who defined Practical Theology as the 'theory of church leadership'.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: Christian leadership is understood as a trans-disciplinary field of study that draws on both theological and other disciplines (such as Management Sciences, Psychology and Sociology). Christian leadership can be pursued as a distinct discipline or a trans-disciplinary field of study, but it cannot be pursued in isolation.

Introduction

Contrary to common practice, this discussion begins with two negative statements. The article is not about the praxis of Christian leaders, nor will it discuss how Christians ought to lead. Rather, it provides a reflection about Christian Leadership as a theological, trans-disciplinary field of study. It attempts to answer the following questions: Can one speak of specifically 'Christian' leadership? To which theological and non-theological disciplines is Christian leadership linked? How can research in the field of Christian Leadership be undertaken, especially research related to Christian Leadership as a subfield within Practical Theology and Theological Ethics? The final question is: Should Christian Leadership be offered as a new theological specialisation?

The purpose of this article is to clarify the nature and range of Christian Leadership as a field of study and discuss its interrelationship with other academic disciplines. Currently, it is a trans-disciplinary field of study, closely linked to and drawing on other theological and non-theological disciplines. In this article, we emphasise the relationship between Christian Leadership and both Practical Theology and Theological Ethics. This is because a great deal of our own research is conducted from within these two disciplines. In addition, several of our postgraduate students are also engaged in research on Christian Leadership within these disciplines. In particular, we discuss the trends and literature that emerge from (South) African and European (especially German) contexts. Africans face many social challenges, and as a result, articles written within this context focus not only on what leadership is but also on the role Christian leaders can play within the Church and society to bring about genuine change and transformation in an African context. Almost 30 years ago, the Dutch expert on intercultural management, Geert Hofstede (1987:13), remarked: 'Most currently popular management theories are made in USA, and implicitly based on US ways of thinking.' This statement on leadership and management theory is still true in general. It is also true in particular for the literature on Christian Leadership. Our discussion therefore seeks to counterbalance the preponderance of the US influence in leadership and management literature by focusing on research in this field from other contexts.

The methodological approach adopted in this article is theoretical in nature. It draws on mainly academic articles published in the field of Christian Leadership. However, it appears that there are very few research articles that explicitly discuss the nature of this field of study. Articles on Christian Leadership are written, consciously or unconsciously, from the perspective of one or more academic disciplines. As shown below, by examining the leadership issues discussed and the academic sources used by the relevant authors, the trans-disciplinary nature of Christian Leadership as a field of study can be detected. Specific methodological issues dealing with Christian Leadership as a field of study within the theological disciplines of Practical Theology and Theological Ethics are also discussed.

Defining Christian leadership

We begin by asking the question whether one can speak of Christian leadership, or should this term be avoided and should it simply be stated that there are persons who are both leaders and Christians. What is actually meant when we speak of 'Christian' leadership? Or, in the words of Hanna (2006:21): 'What is "Christian" about Christian Leadership?'

In our view, there are two legitimate ways in which the term 'Christian' leadership can be used. Firstly, it can refer to leaders who have leadership responsibilities within a Christian organisation. Such organisations are rooted in the Christian faith and have a specifically Christian purpose, for example, a Church congregation, Christian monastery, mission agency, non-profit organisation (NPO) or non-governmental organisation (NGO). Thus, 'Christian' leadership in this instance means leadership by Christians within a Christian organisation.

If we limit the understanding of Christian leadership to this first definition, there would be no need for a trans-disciplinary study of Christian leadership because leadership in church-based organisations could be dealt with in sub-disciplines such as Practical Theology, Theological Ethics or Missiology. However, 'Christian' leadership is also exercised by leaders1 who operate within 'secular' organisations such as business companies, organs of government, labour organisations and NPOs that no longer have, or never had, a specifically Christian foundation. In such settings, there are Christians who want to offer leadership that reflects a Christian worldview, anthropology and set of values. We do not say that Christian Leadership is automatically better leadership. We recognise that each leader has assumptions - wittingly or unwittingly - about 'the world', values and human beings and that these assumptions influence their leadership style. This truth was spelled out in 1960 by the management author Douglas McGregor ([1960] 1985:x): 'The key question of top management is: "What are your assumptions (implicit as well as explicit) about the most effective way to manage people?"' When we speak of Christian leadership, we are referring to those leaders who explicitly draw on their faith and Christian worldview. If such leaders develop the skills, competence and moral character required, they could be exemplary leaders. However, simply claiming to be a Christian leader does not mean that such a person will be a better leader.

Over the last few decades, many books on leadership that address both Church leaders and leaders in general have been written from a Christian perspective. The most successful author in this area is probably the North-American John Maxwell, whose best-selling book is entitled The 21 irrefutable laws of leadership (1998). The most prominent German author in the area of Christian Leadership is the Benedictine monk Anselm Grün. His book on leadership (Grün 1999) is based on the Rule of St Benedict,2 but it is written so that many business people find it relevant and helpful. Also, the Christian conference 'Kongress christlicher Führungskräfte' (2013) is held every second year in Germany, and it attracts almost 4000 attendees, mostly from the business world. These few examples show that Christian leadership extends beyond leadership in Christian organisations.

In addition to including vital ethical dimensions, Christian leadership is also based on Christian spirituality. Christians are people who follow Christ (Ac 11:26), are part of the body of Christ (1 Cor 12:12, 13) and worship a Trinitarian God (2 Cor 13:13). Henri Nouwen (1989), the well-known writer on Christian spirituality, wrote a deeply insightful reflection on the implications for leadership in the temptations faced by Jesus (Mt 4:1-11; Mk 1:12-13; Lk 4:1-11). Kretzschmar (2006) and Nullens (2013) have also recently discussed the link between spirituality and leadership, and the Christian Leadership Centre at St. Andrews University (North Carolina) stresses that Christian leadership happens'... under the influence of the Holy Spirit' (Hanna 2006:21).

There are many definitions of leadership. Neuberger (2002:12-15) lists 39 different definitions drawn from the German literature on leadership. The authors of this article share a passion for short definitions, the shorter the better. Greenleaf, the author of the book on servant leadership, provides us with this very short definition, 'The only test of leadership is that somebody follows - voluntarily' (Greenleaf 1998:31).3 In our definition of leadership, the word 'voluntarily' is omitted, because we regard formal authority as a legitimate form of power (Kessler 2010:539-544, 2012:4046). The following definitions are thus suggested: 'A leader is a person whom other persons follow.' And therefore: 'A Christian leader is a person who follows Christ and whom other persons follow.'4

Although we recognise the Bible as a primary source for Christian faith and practice, the term 'Biblical leadership' is avoided in a general sense because there are many pitfalls in constructing a definition of 'Biblical' leadership (Kessler 2013). Hence, the term 'Biblical leadership' is only used when leadership is referred to as it was exercised in the Bible by leaders like Moses, Deborah, the various kings of Israel and Judah, Nehemiah and the leaders within the New Testament churches. Whilst it is true that the Bible provides many ethical guidelines about leadership that remain valid, Christian leadership cannot be exercised today in exactly the same way as it was by those leaders. Inspired by God, leaders in the Bible exercised their faith within their different contexts but also sought to transform their socio-cultural, political and economic contexts. Similarly, the current practice of Christian leadership has to take into account many contemporary contexts and cultures without being determined by them.

Positioning Christian Leadership within the academic disciplines

Christian Leadership viewed primarily as church leadership is traditionally a study field within Practical Theology. Due to the broader understanding of Christian leadership outlined above, it is necessary to move beyond the traditional focus of Practical Theology as it is mainly concerned with the life and ministry of the Church within different contexts. The broader meaning of Christian leadership will require investigating leadership within secular organisations such as business companies or NPOs. This means moving into discussions with the disciplines of the economic and management sciences on matters related to leadership and ethics. As theologians, we do not seek to compete with academics in terms of their specific competence. However, academic research and tuition are increasingly moving beyond the narrow borders of traditional disciplines. Areas of interest such as business ethics are becoming more and more important on both a theoretical and practical level. Thus, Christian Ethics becomes a natural meeting point between the economic sciences and theology. This is especially true when certain leaders of business organisations are known to be Christians and refer explicitly to their Christian worldview and ethical convictions. In this instance, Christian Leadership could be seen as a field of study within Theological Ethics.

Certainly, Christian Leadership can also become a field of study within Missiology. Today, the borderline between Practical Theology and Missiology is less clear than it used to be in the days when mission was a one-way movement from Christianised countries to other countries.5 As more congregations are moving from being mono-cultural to being multi-cultural, it is especially the cross-cultural effects of Christian leadership that are addressed in Missiology.

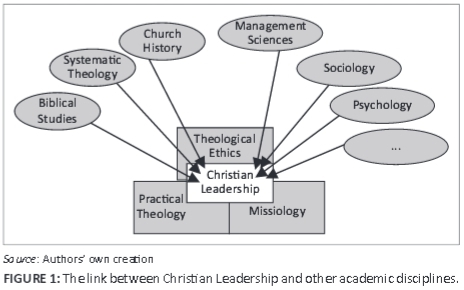

Thus far, three different theological areas where Christian Leadership can be studied have been identified: Practical Theology, Theological Ethics and Missiology. Obviously, research on Christian leadership relies on insights from many other theological6 and non-theological disciplines. For example, biblical scholars consider leaders in different periods in the Old Testament such as Moses, Aaron and Miriam (Usue 2006:635-656), King Lemuel (Harris 2002:61-73) andJeremiah (Wessels 2010:483-501). Other biblical scholars have conducted research on leaders in the New Testament. Feddes (2008:274-299) discusses the leadership and mission of the early church, using the 'household codes' and highlights the importance of the home, household, family and extended family, and Stenschke (2010:503-525) analyses the leadership of Barnabas and Paul. There are also several studies on historical church leaders, for instance Bentley's discussion of John Wesley (2010:551-565) and Mbaya's (2009:22-41) analysis of Anglican Church leaders in Central Africa. Or, one might study how leadership is manifested in particular countries such as Switzerland (Russenberger 2010:631-649) and Russia (Reimer 2010:631-649). Since all leadership studies draw on anthropology, and Church leadership specifically draws on ecclesiology, Systematic Theology is also a key discipline for leadership studies. Christian Leadership, thus, draws on all of the theological disciplines.

As noted previously, Christian Leadership is also linked to non-theological disciplines. Linking up with management science, we may ask: How are organisations structured? Noel Pearse (2011:1-7) from the Business School at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, draws on the discipline of Business Management to evaluate the role of strategic church leadership during periods of transition, using, amongst others, the concept of organisational social capital. With reference to psychology, we can ask: What motivates or demoralises people? Or linked to sociology, we can ask: What do I have to know about social groups and group dynamics if I am to be an effective leader?

The diagram in Figure 1 explains the relationship between Christian Leadership and other academic disciplines. Christian Leadership is a field of study that usually occurs in one of these three disciplines: Practical Theology, Theological Ethics or Missiology. In addition, other disciplines contribute to the area of Christian Leadership. These include the theological disciplines like Biblical Studies, Systematic Theology and Church History and the non-theological disciplines like Management Sciences, Sociology and Psychology.

In what follows, we describe two approaches in greater detail: Christian Leadership in the context of Practical Theology and Christian Leadership in the context of Theological Ethics.

Christian Leadership within the context of Practical Theology

Today, Practical Theology is a theological discipline that incorporates different sub-disciplines like liturgics, homiletics, poimenics7, religious education and diaconology (Nicol 2000:5-9). Church Leadership, sometimes called Church Management or 'Kybernetik' as in the German Protestant tradition (Breitenbach 1994:27; Meyer-Blanck 2007), is thus a sub-discipline within Practical Theology. There are many different ways to structure the vast area of Practical Theology into different subfields. These differences emerge, firstly, because of different ecclesial confessions (e.g. Roman Catholic, Protestant or Orthodox), secondly, because of different cultures (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands, North America or South Africa; cf. Heitink 1999:112-121) and, thirdly, because of different approaches to Practical Theology (e.g. Practical Theology seen as Pastoral Theology or seen as theory of action).

When dealing with Christian Leadership in the context of Practical Theology, it is valuable to examine the actual beginning of the academic discipline of Practical Theology. The German professor Friedrich Schleiermacher is regarded as the founder of Practical Theology as a discipline in its own right (Gräb 2000:87). Heitink (1999:22) calls him 'the father of practical theology' and notes that 'Schleiermacher wanted to give theology its place in the scientific arena' (ibid:26). For the purpose of this article, it is interesting to note that Schleiermacher defines Practical Theology as the 'Theory of Church leadership' (cf. Breitenbach 1994:46; Gräb 2000:67).

In his famous Kurze Darstellung [A brief outline on the study of theology], the first edition of which was published in 1811 and a second, larger edition in 1830, Schleiermacher divided theology into three parts - philosophical, historical and practical theology. In the first edition, Schleiermacher (2002:67) defines'... Philosophical Theology as the root of the whole of theology' (Introduction §26) and'... Practical Theology as the crown of theological study' (introduction §31). Practical Theologians often like to quote the last sentence, but it must be conceded that Schleiermacher did not refer to the crown of a king but to the crown of a tree.8

The quote below is from the second edition of Schleiermacher's Brief outline, which has the useful feature that its 338 paragraphs are numbered from the beginning to the end. Schleiermacher (1850) defines Practical Theology as knowledge about Church Leadership:9

§25. The purpose of Christian Church-Guidance is both extensively and intensively conservative and progressive; and the knowledge relating to this activity forms a Technology which we, grouping together all its different branches, designate by the name, Practical Theology. (p. 101)

Schleiermacher (1850) then distinguishes two sorts of leadership:

§271. ... There is, therefore, a guiding activity which has for its object the individual Congregation as such, and which, accordingly, continues to be merely local in its character - and a guiding activity directed toward the whole, which has for its object the organic Union of Congregations, that is, the Church. (pp. 191-192)

§274... and we denominate the guiding activity which is directed towards the whole, Church-Government, and that which is directed towards the individual local Congregation, Church-Service. (p. 194)

Consequently, Schleiermacher's exposition on Practical Theology consists of two sections: the introduction or Section

1 on 'The principles of church-service' (§§277-308; German original: [Die Grundsätze des Kirchendienstes]) and Section 2 on 'The principles of church government' (§§309-334, German original: [Die Grundsatze des Kirchenregiments]). The subject of the first section is 'leading a local congregation' and that of the second section is 'leading the Church as whole'.10 According to Schleiermacher (1850), this is what Practical Theology is about:

§275. The contents of Practical Theology are included exhaustively in the Theory of Church-Government (in the more restricted sense) and the Theory of Church-Service. (p. 194)

Schleiermacher subsumes every pastoral activity under the heading 'Soul-guidance' (§263, German original: [Seelenleitung]) as there are sermons (§284f.), system of worship (§286ff.) and pastoral care (§291ff.).11 Thus, homiletics, liturgics and catechetics are part of the academic discipline of Practical Theology, defined as Theory of Church-guidance. Schleiermacher argues that leading the Church as a whole, that is, Church government, is mainly done by the means of the 'internal Church-Constitution' (§310, §312).

So, if - according to Schleiermacher - Practical Theology is the crown of theological studies and Practical Theology is essentially about Church leadership, then Church Leadership must be the most appealing field of study!

As mentioned above, Schleiermacher's views have been modified. In academic circles today, Church Leadership is seen as only one of many subfields of Practical Theology. Since 1985, a great many books on leadership have been published in the field of management studies, and these have been accompanied by an increase in interest concerning Christian Leadership. For instance, the establishment of the Willow Creek Association, the popularity of Bill Hybels' books on leadership (e.g. Hybels 2002) and the success of the Willow Creek leadership summits held in the US and worldwide (Willow Creek 2013) reflect a growing interest in Christian Leadership. In Germany today, more church ministers attend Christian Leadership conferences than conferences on counselling or preaching. It seems that two centuries after the first edition of Schleiermacher's Kurze Darstellung (1813), the field of Church Leadership has indeed acquired the prestige of a 'crown'.

Obviously, the understanding of Church Leadership and Practical Theology has changed tremendously during the last century. The growth of interest in empirical studies since the 1960s has meant that empirical theology has become important within Practical Theology. Research in the subfield of Christian Leadership now often includes an element of empirical research (see Dinter, Heimbrock & Söderblom 2007; Van der Ven 1998). Thus, sociological methods have become an indispensable tool of practical theologians.

There are many possible research questions concerning Christian leadership within Practical Theology. Burnout as a result of overly demanding job situations is, for instance, an increasing challenge in Germany. It has been discovered that church ministers demonstrate an over-average risk of suffering from burnout. This often leads to early retirement or a change of job. Thus, the prevention of burnout amongst church ministers has become a research issue whether they work in the Protestant churches (Van Heyl 2003) or in the context of evangelical youth-mission organisations (Schmidt 2012).

Another research issue is the question of how church leadership can be exercised in different contexts and different cultures (see Chima 1984; Mushanga 1971; Russenberger 2010). Two centuries ago, Schleiermacher (1850) stated the impossibility of a single universal form of leadership:

§272. ... with the present diffusion of Christianity, outward reasons would make the existence of a universal Church-Guidance, comprehending all Christian Congregations upon the earth, a thing impossible. (p. 193)

Practical Theology has always been a discipline where practical involvement and scientific interest meet (or at least should meet). Again, this combination was already insisted upon by Schleiermacher (1850):

§258. Practical Theology, therefore, is for those only in whom an interest in the welfare of the Church, and a scientific spirit, exist in combination. (p. 187)

Unfortunately, there is often a dichotomy between the two worlds of practitioners that do not bother about the sciences and scientists that do research for the sake of research. Our approach is different. We are interested in research on Church Leadership because we want to improve current church leadership, we want to support Christians who take the risk of moving ahead, and thus, we want to contribute to the welfare of both the church and society.

If we want to follow the point of view expressed in Schleiermacher's paragraph §258, the question arises: How do we combine practical involvement and scientific knowledge? There are some models of praxis cycles that can be used to answer this question. We recommend Kritzinger's (early) model of the praxis cycle (Kritzinger 2002:147-152). The advantage is that it is quite a simple model, consisting of the five steps: involvement, context analysis, theological reflection, spirituality and planning. Thus, this praxis cycle is a good starting point for the integration of research and practical involvement in the field of Christian Leadership within the discipline of Practical Theology.

Christian Leadership within the context of Theological Ethics

In this section, we seek to define Theological Ethics, outline some of the different ecclesial or theological approaches to this discipline and note some key areas of research in Christian Leadership in an African and German context from an ethical perspective. We also note how different scholars approach these fields of study. Like Christian Leadership, Theological Ethics can be described as interdisciplinary in nature. This is because, although its focus is on what may be considered to be right, good and wise behaviour or on what is just and loving at a personal, communal, social or global level, it often 'borrows' theoretical knowledge from other theological and non-theological disciplines.

In this article, Theological Ethics is understood as synonymous with Christian Ethics. It is primarily concerned with one's overall ethical worldview, what is considered to be loving, right and good (moral norms and values), the application (and questioning) of these norms in personal and social life, the formation of moral character and moral conduct. The German Catholic theologian Schockenhoff (2007) defines Theological Ethics in the context of Christian theology as:

... a theory of human behaviour under the claim of the Gospel. [Theological ethics] investigates a good life and right actions from the perspective of the Christian faith, and considers the implications for such life and action as resulting from the fact that the questions about their ultimate goal will be answered in the light of a specific concept of human fulfilment, a concept based on Biblical revelation. (pp. 19-20)12

In the 21st-century context, there is an extensive debate about what can be considered to be real, good, right, true and wise. Although debates, revisions, challenges and new insights continue to emerge, Christian Ethics is based on the Bible and on over 2000 years of Christian theology, tradition and experience. Theological Ethics stands on the foundation of a Creator God who is good. Hence, researchers in Christian Ethics are both motivated and inspired by the moral vision of a good creation, which, although now fallen, can be saved. Redeemed human beings imbued with moral insight and character need to be formed so that, individually and collectively, they can exemplify the richness of the new creation. In this respect, the link between Theological Ethics and Christian Leadership is twofold. Firstly, Christian leaders need to interrogate the degree of their own active co-operation with the Holy Spirit in the process of personal moral formation and the formation of churches as moral communities. Secondly, they need to interrogate their own understanding of what is right and good, prior to seeking to effect the genuine transformation of structures and practices in local and global societies and the drastic improvement of our human interaction with all of creation.

Research in Christian Leadership, or any other academic field, is based on a theoretical paradigm or framework of understanding. A key part of this paradigm is the various academic disciplines upon which research in Christian Leadership draws. Another dimension of this theoretical paradigm is the ecclesial tradition of the relevant researcher. For example, Theological Ethics could be approached from the perspective of Catholic, Protestant, Evangelical, Orthodox or Charismatic Theology. (Generally Protestants will use the term Theological or Christian Ethics whereas Catholics more generally use the term Moral Theology). Within these larger church groupings, there are several theological traditions (e.g. Thomist, Calvinist, Evangelical, Fundamentalist, Barthian, Liberal, Liberationist, Feminist or Africanist) from which researchers draw. Even if the researchers are, for instance, Protestants, they may be influenced by the theological thinking of a particular denomination (e.g. Methodist, Lutheran or Baptist). In addition, the geographical and social context within which Christian Leadership is studied is vitally important. Not only do the diverse contexts of the United States of America, South Africa, Germany and England affect the leadership studies produced in them, but the literature produced in the various countries tends to influence their contexts. Beyond the influence of one's country or continent, the role of culture, ethnic identity, race, gender and class is also important. Thus, it is essential for researchers to become conscious of their own theoretical paradigm and broaden their understanding by reading material written from other perspectives.

Although some authors use the expressions ethical leadership and moral leadership interchangeably, it is useful to note that ethicists commonly draw a distinction between ethics and morality. As a discipline within Philosophy or Theology,13 ethics investigates the question: 'What is ethical?' This means that what is regarded as right, good or wise within a particular society, culture, organisation or local church is the subject of critical, ethical reflection. The term 'morality' then refers to the actual behaviour that expresses moral norms and values at a personal, communal, social or global level. Immoral behaviour is that which disregards or is in conflict with what is regarded as moral. The value of such a distinction is that what is regarded as morally right can be questioned, and where necessary, such a moral perspective can be revised, a point to which we return below.

Theological ethics is both intensely theoretical and determinedly practical, no matter which social context it seeks to address. Theological ethics seeks to understand who God is and what the nature of reality is. It seeks to understand how to live in the world as God's children, ambassadors and moral agents. Hence, Christian leaders are concerned with the clarification and application of moral norms and values to concrete life. Obviously, to speak of reality and the world is very broad. Hence, Theological Ethics is often subdivided into a number of different fields of study. Christian leaders in the medical field such as doctors, administrators, senior nurses or relief workers will have an interest in bio-ethics whilst other Christian leaders may pursue environmental ethics. Globally, the pursuit of social ethics was and remains a central area of intellectual and practical concern. More than four decades ago, Mushanga (1971) argued that a new understanding of Christian ministry and leadership needs to emerge in Africa to address urgent social needs:

In a society which is undergoing rapid social change, in which the majority of the people live at subsistence level, where ignorance is rampant and diseases are endemic ... The church leadership should descend from the pulpit and go to the people in their natural habitat and try to see in what situations it could be of assistance to them. (p. 35)

Writing from within the Nigerian context, Enegho (2011:529535) observes that a major cause of Africa's social problems is the behaviour of the domineering, self-serving new 'elite' class of leaders. He (ibid:523) goes on to say that, against the trend of widespread corruption, '... Christians ought to blaze the trail in displaying unparalleled integrity and invariably sow seeds of integrity in the lives of others by their living examples'. Family and sexual ethics and various forms of feminist, womanist and gender ethics are also matters of concern for Christian leaders all over the world. Furthermore, as already noted, business and organisational ethics or the practice of leadership within a certain organisation (Hornstra-Fuchs & Hornstra 2010) are additional areas of importance for research. This wide range of ethical issues reveals the close link between Theological Ethics and Christian Leadership.

By drawing a distinction between ethics and morality, their influence on each other and social contexts is revealed. It can be seen that people's ethical worldviews and moral norms affect their moral behaviour. More simply, ethical convictions lead to moral action. Equally, practical experience and/or empirical research on moral (or immoral) behaviour may result in a revision of ethical worldviews or theoretical understandings. Thus, Chima (1984:331), a Roman Catholic priest and educator, writes from the Malawian and Kenyan contexts about the need to '... broaden and diversify the concept and practice of ministry' and seeks to critique '... the whole structure of authoritarian conditioning'.14 Based on his experience, he argues that the nature of priestly authority must correctly be conceived, and the traditional African, pre-colonial limitations on the authority of kings or chiefs must be drawn upon if Christian leadership is to be correctly exercised in an African setting. Another example is that of Bolaj (2007:1-5) who argues that that immoral, patriarchal patterns of behaviour derived from aspects of the thinking of both Western missionaries and traditional African culture are being challenged in those Pentecostal churches that are promoting women to leadership positions.15 In other words, ethical norms and values are not only in need of being defined and applied, but they can also be questioned and clarified or revised in research that combines an interest in ethics and leadership.

We have seen that ethical reflection is essential to the credible practice of Christian leadership. However, the identification, application or questioning of ethical norms and values does not provide a complete picture of the concerns of Theological Ethics as they relate to Christian Leadership. The moral nature and effect of the vision of a leader also needs to be investigated. What will the effects of the pursuit of this vision be, both on the leaders themselves and on the lives of those impacted by the leaders' vision? Or what actions will result from the leaders' motives or intentions? Furthermore, what methods or means will be employed by the leaders? Are these moral in nature? Moral discernment and wisdom are thus key aspects that require attention in the field of Christian Leadership studies.

What then about the whole area of moral and spiritual formation? Many of the problems experienced in terms of leadership are due to the absence in society today of moral character and conduct (e.g. intimidation, exploitation, the lack of fair processes, unjust decisions, violence and marginalisation). These could occur at many levels and within a variety of sectors (e.g. interpersonal, family and workplace relationships and within national and international sociopolitical or economic processes and structures). Hence, without a process of Christian discipleship leading to becoming mature in Christ, ethical reflection and research will not lead to growth in wisdom, moral courage and sacrificial action. For instance, the interrelationship between moral character, decision making and community (Connors & McCormick 1998) or the ethical issues connected to leadership and the development of moral agency in different cultures can be researched (Kretzschmar 2010:567-588). In short, research within the field of Christian Leadership, when approached from within the wide-ranging discipline of Theological Ethics, can clarify what is right and wrong in our churches and societies, how these moral norms are arrived at, how individuals or communities become morally formed (or malformed) and what can be done to live as God's representatives in a complex world.

Conclusion

We are convinced that research in the field of Christian Leadership is both necessary and important. We have argued that Christian Leadership is a typical example of trans-disciplinary research that, in most cases, takes place within in the theological disciplines of Ethics, Practical Theology and Missiology. However, such research also needs to draw on several other theological and non-theological disciplines.

Given that research in the field of Christian Leadership can be dealt with in the context of many current disciplines, it may not be necessary to establish it as a separate, distinct or specific discipline. Also, it is well known that current scholarship already consists of a plethora of disciplines. However, at some universities and theological colleges, academics are responding to a felt need in the church and society and are offering courses or even specific degrees in Christian Leadership. Such scholars and institutions may wish to develop Christian leadership further as a distinct discipline. Nevertheless, whether pursued as a trans-disciplinary field of study or a new discipline, studies in Christian Leadership cannot be pursued in isolation. Therefore, we argue that Christian Leadership needs to be treated as a field of study that can integrate knowledge and analysis from a range of academic disciplines and practical contexts. It is as a trans-disciplinary field of study that Christian Leadership can make a notable contribution to both academia and contextual practice.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the writing of this article, but V.K. (Akademie für christliche Führungskräfte) was mainly responsible for the section on Christian Leadership within the context of Practical Theology and L.K. (University of South Africa) for the section on Christian Leadership within the context of Theological Ethics.

References

Bentley, W., 2010, 'The formation of Christian leaders: A Wesleyan approach', Koers 75(3), 551-565. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.96 [ Links ]

Breitenbach, G., 1994, Gemeinde leiten: Eine praktisch-theologische Kybernetik, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Berlin, Köln. [ Links ]

Bolaj, O.B., 2007, 'Forging identities: Women as participants and leaders in the Church among the Yoruba', Studies in World Christianity 13(1), 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.3366/swc.2007.13.1.1 [ Links ]

Chima, A., 1984, 'Leadership in the African Church', African Ecclesial Review 26(6), 331-337. [ Links ]

Connors, R.B. & McCormick, P.T., 1998, Character, choices & community, HarperCollins, New York. [ Links ]

De Waal, E., 1995, A life-giving way: A commentary on the Rule of St Benedict, Geoffrey Chapman, London. [ Links ]

Dinter, A., Heimbrock, H.-G. & Söderblom, K. (eds.), 2007, Einführung in die Empirische Theologie: Gelebte Religion erforschen, Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Gottingen. [ Links ]

Enegho, F.E., 2011, 'Integrity in leadership and the challenges facing Africa: A Christian response', African Ecclesial Review 53(3/4), 522-537. [ Links ]

Feddes, D.J., 2008, 'Caring for God's household: A leadership paradigm among New Testament Christians and its relevance for church and mission today', Calvin Theological Journal 43, 274-299. [ Links ]

Grab, W., 2000, 'Praktische Theologie als Theorie der Kirchenleitung: F. Schleiermacher', in C. Grethlein & M. Meyer-Blanck (eds.), Geschichte der Praktischen Theologie: Dargestellt anhand ihrer Klassiker, pp. 67-110, Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig. [ Links ]

Greenleaf, R.K., 1998, The power of servant leadership, L.C. Spears (ed.), Berret-Kohler, San Francisco. [ Links ]

Grun, A., 1999, Menschen führen, Leben wecken: Anregungen aus der Regel des heiligen Benedikt, 2nd edn., Vier-Türme-Verlag, Munsterschwarzach. [ Links ]

Hanna, M., 2006, 'What is "Christian" about Christian leadership?', Journal of Applied Christian Leadership 1(1), 21-31. [ Links ]

Harris, J.I., 2002, 'The king as public servant: Towards an ethic of public leadership based on virtues suggested in the Wisdom Literature of the Old Testament', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 113, 61-73. [ Links ]

Hearne, B., 1982, 'Priestly ministry and Christian community', African Ecclesial Review 24(4), 221-233. [ Links ]

Heitink, G., 1999, Practical theology: History, theory, action domains, Wm. B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G., 1987, 'The applicability of McGregor's theories in South East Asia', Journal of Management Development 6 (3), 9-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb051642 [ Links ]

Hornstra-Fuchs, F.A.S. & Hornstra, W.L., 2010, 'Female leaders in an international evangelical mission organisation: An empirical study of Youth with a Mission in Germany', Koers 75(3), 589-611. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.98 [ Links ]

Hybels, B., 2002, Courageous leadership, Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Kessler, V., 2010, 'Leadership and power', Koers 75(3), 527-550. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.95 [ Links ]

Kessler, V., 2012, Vier Führungsprinzipien der Bibel: Dienst, Macht, Verantwortung, Vergebung, Brunnen, Gießen. [ Links ]

Kessler, V., 2013, 'Pitfalls in "Biblical" leadership', Verbum et Ecclesia 34(1), Art. #721, viewed 14 March 2013, from http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v34i1.721 [ Links ]

Kongress christlicher Führungskräfte, 2013, viewed 11 July 2013, from http://www.fuehrungskraeftekongress.de [ Links ]

Kretzschmar, L., 2006, 'The indispensability of spiritual formation for Christian leaders', Missionalia 34(2/3), 338-361. [ Links ]

Kretzschmar, L., 2010, 'Cultural pathways and pitfalls in South Africa: A reflection on moral agency and leadership from a Christian perspective', Koers 75(3), 567-588. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.97 [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J., 2002, 'A question of mission - a mission of questions', Missionalia 30(1), 144-173. [ Links ]

Maxwell, J., 1998, The 21 irrefutable laws of leadership: Follow them and people will follow you, Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville. [ Links ]

Mbaya, H., 2009, 'The making of African Anglican bishops in Central Africa: The case of Josiah Mtekateka in Malawi 1950-1977', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 135, 22-41. [ Links ]

McGregor, D., [1960] 1985, The human side of enterprise, 25th anniversary printing, McGraw-Hill, Boston. [ Links ]

Meyer-Blanck, M., 2007, 'Gemeindeleitung: Kybernetik/Soziale Systeme/Leitbilder/Leitungsstrukturen', in W. Gräb & B. Weyel (eds.), Handbuch Praktische Theologie, pp. 507-518, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh. [ Links ]

Mushanga, M.T., 1971, 'Church leadership in a developing society', African Ecclesial Review 13(1), 33-40. [ Links ]

Nicol, M., 2000, Grundwissen Praktische Theologie: Ein Arbeitsbuch, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Neuberger, O., 2002, Führen undführen lassen, 6th edn., Lucius & Lucius, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Ngunjiri, F.W., 2010, 'Lessons in spiritual leadership from Kenyan women', Journal of Educational Administration 48(6), 755-768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09578231011079601 [ Links ]

Nouwen, H.J.M., 1989, In the name of Jesus: Reflections on Christian leadership, Darton, Longman and Todd, London. [ Links ]

Nullens, P., 2013, 'Towards a spirituality of public leadership: Engaging Dietrich Bonhoeffer', International Journal of Public Theology 6, 1-23. [ Links ]

Pearse, N.J., 2011, 'Effective strategic leadership: Balancing roles during Church transitions', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 67(2). Art. #980, 7 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v67i2.980 [ Links ]

Reimer, J., 2010, 'When western leadership models become a mixed blessing', Koers 75(3), 631-649. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.100 [ Links ]

Russenberger, M., 2010, 'Leadership style in Swiss evangelical churches in the light of their historically shaped leadership culture', Koers 75(3), 631-649. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.101 [ Links ]

Schleiermacher, F., 1850, Brief outline of the study of theology, drawn up to serve as the basis of introductory lectures, transl. W. Farrer, T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Schleiermacher, F., 2002, Kurze Darstellung des theologischen Studiums (1811/1830), Berlin, Walter de Gruyter, New York. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110864809 [ Links ]

Schockenhoff, E., 2007, Grundlegung der Ethik, Ein theologischer Entwurf, Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau. [ Links ]

Schmidt, H., 2012, 'Burnoutpräventive Mitarbeiterführung im Kontext des Rings Missionarischer Jugendbewegungen in Deutschland', MTh thesis, Department of Practical Theology, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Stenschke, C.W., 2010, 'When the second man takes the lead: Reflections on Joseph, Barnabas and Paul of Tarsus and their relationship in the New Testament', Koers 75(3), 503-525. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.94 [ Links ]

Usue, E.O., 2006, 'Leadership in Africa and in the Old Testament: A transcendental perspective', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 62(2), 635-656. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v62i2.361 [ Links ]

Van der Ven, J., 1998, Practical theology: An empirical approach, Peeters Publ., Leuven. [ Links ]

Van Heyl, A., 2003, Zwischen Burnout und spiritueller Erneuerung: Studien zum Beruf des evangelischen Pfarrers und der evangelischen Pfarrerin, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main. [ Links ]

Vest, N., 1997, Friend of the soul: A Benedictine spirituality of work, Cowley, Boston. [ Links ]

Wessels, W.J., 2010, 'Connected leadership: Jeremiah 8:18-9:3', Koers 75(3), 483-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koers.v75i3.93 [ Links ]

Willow Creek, 2013, viewed 22 November 2013, from http://www.willowcreek.com/events/leadership [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Louise Kretzschmar

PO Box 392

University of South Africa 0003

South Africa

kretzl@unisa.ac.za

Received: 09 Feb. 2014

Accepted: 10 Sept. 2014

Published: 15 Apr. 2015

1. We recognise that Christians in all walks of life can exercise some leadership within the Church and society, but this article focuses on those who are designated as leaders.

2. See also De Waal (1995:187-199) and Vest (1997).

3. A distinction can be drawn between a leader who has moral authority but no official position and a leader who exercises power due to a position but has no moral authority. Equally, power, when exercised wisely and fairly, is a legitimate use of power. Such leaders exercise moral authority and are regarded as credible leaders.

4. See Bentley (2010:551-565) for a discussion of how leadership roles can be extended to more people through processes of deliberate formation.

5. It has long been disputed whether Missiology should be treated as a sub-discipline of Practical Theology. See footnote 11 for Schleiermacher's view in §298.

6. See the special issue on Christian Leadership published by the journal Koers (75/3) in 2010. A further issue, Koers (79/2), appeared in September 2014.

7. Or pastoral theology (from the Greek poimen, meaning 'shepherd').

8. In his lectures on Practical Theology, Schleiermacher explains this 'crown' metaphor. 'Practical Theology is the crown of theological study because it presupposes everything else; it is also the final part of the study because it prepares for direct action' (in Heitink 1999:26-27).

9. Schleiermacher actually used the German word 'leiten' (to lead), although the English translator from 1850 opted for the translation 'guiding'.

10. In §276 Schleiermacher (1850:194) claims, 'The order of arrangement is, in and of itself, a matter of indifference. We prefer to begin with the department of Church-Service, and to let that of Church-Government follow.' In the first edition, Schleiermacher opted for the opposite order.

11. Schleiermacher (1850:202) even mentions mission here: '§ 298. Conditionally, the Theory of Missions might also find a point of connexion here, which, up to the present time, is as good as altogether wanting.' He was thus the first Protestant theologian who gave Missiology a separate place in the University but, of course, in his logic as a subfield of Practical Theology.

12. Translated by Elke Meier, original wording: '[Theologische Ethik] versteht sich als eine Theorie der menschlichen Lebensfuhrung unter dem Anspruch des Evangeliums. Sie fragt nach dem guten Leben und richtigen Handeln in der Perspektive des christlichen Glaubens und bedenkt die Konsequenzen fur dieses Leben und Handeln, die sich daraus ergeben, dass die Frage nach seinem letzten Ziel im Lichte einer bestimmten, nämlich einer der biblischen Offenbarung entnommenen Vorstellung menschlicher Erfüllung beantwortet wird' (Schockenhoff 2007:19-20).

13. Moral philosophy is a sub-discipline of Philosophy, and Christian Ethics is usually taught either as a distinct discipline within Theology or as part of Systematic Theology (or Dogmatics) or sometimes Practical Theology. Other theological disciplines such as Biblical Studies and Missiology may also address ethical issues.

14. Hearne (1982:221-223) discusses revised understandings of the roles of Catholic priests in African contexts.

15. See Ngunjiri (2010:755-768) for a discussion of female spiritual leadership in Kenya.