Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Verbum et Ecclesia

versão On-line ISSN 2074-7705

versão impressa ISSN 1609-9982

Verbum Eccles. (Online) vol.34 no.2 Pretoria Jan. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Beyond monotheism? Some remarks and questions on conceptualising 'monotheism' in Biblical Studies

Christian FrevelI, II

IFaculty of Catholic Theology, Ruhr-Universitát Bochum, Germany

IIDepartment of Old Testament Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In the first part of this article I outline serious objections against the concept of monotheism. I will ask whether the ambiguity and the problem discredit the concept of monotheism as inappropriate for Biblical Studies, or whether it calls for differentiation. In the argument following thereupon, the concept is found to be more useful to describe certain stages of the conceptual and linguistic development of Israelite religion. The term and concept of monotheism in Biblical Studies is necessary, but not sufficient, if we want to reconstruct the religious history of Israel, Judah, Yehûd and Early Judaism or Judaisms. In this article I propose categories such as implicit monotheism, intolerant monolatry, implicit exclusion, explicit uniqueness, monotheism as implication et cetera, which are especially useful if we want an accurate description of the statements. This makes the category of monotheism useful as heuristic and relational category.

Introduction

In 1991 John Hayman called 'monotheism' a misused word in Jewish Studies and wrote solid considerations against it with the following tenor (Hayman 1991):

it is hardly ever appropriate to use the term monotheism to describe the Jewish idea of God, that no progress beyond the simple formulas of the Book of Deuteronomy can be discerned in Judaism before the philosophers of the Middle Ages, and that Judaism never escapes from the legacy of the battles for supremacy between Yahweh, Ba'al and El from which it emerged. (p. 2)

By focusing on the post-biblical Jewish traditions he tried to convince his audience that 'the pattern of Jewish beliefs about God remains monarchistic throughout. ... God is the sole object of worship, but he is not the only divine being' (Hayman 1991:15). The general critique towards Jewish religion from postexilic times to the Middle Ages was a threat to traditional views, but questioning the concept of biblical monotheism was not new at all. Whether the philosophical descriptor 'monotheism' matches the biblical reality at all is a well-known question in Biblical Studies. So for example, Walter Moberly entitled his paper 'How appropriate is "monotheism" as a category for biblical interpretation?' (Moberly 2004). Gregor Ahn has questioned the capability of the diametrical conceptualisation of monotheism/polytheism in religious studies as a whole. He sees some suitable advantage of the term in emic studies, but not at all in its use as an etic category: 'Als Klassifikationsmuster eines metasprachlichen Wissenschaftsdiskurses wird das Monotheismus-Polytheismus-Schema dagegen zunehmend fragwürdiger' (Ahn 2003:9).1 In sum, there are several and in some way independent threads questioning the 'monotheism'-concept of Biblical Studies. Bringing the lines together, the Society of Biblical Literature International Meeting in London 2011 held a panel discussion captioned 'The concept of monotheism: Should it have a future in Biblical Studies?', which included papers by Rainer Albertz, Bob Becking, Philip Davies, Nathan MacDonald, Diana Edelman, André Lemaire, Saul M. Olyan, Thomas Römer, Rüdiger Schmitt, Konrad Schmid, Mark S. Smith and myself.2 The following article, which stems for the largest part from my contribution to that London seminar, adds some questions and remarks to the question of appropriateness of 'monotheism' in Biblical Studies. I will relate to the discussion on monotheism in recent decades, but I do not intend here to go deeper into details of the Forschungsgeschichte [history of research] of this problem.

Can history avoid future? Monotheism as backlash

Is it the right question to ask whether the concept of monotheism should have a future in Biblical Studies? Can we ever get rid of the concept of monotheism? We should not delude ourselves by assuming that our concepts could be abandoned so easily. It is not just a decision of 'yes' and 'no'. Is it not the same with other terms and concepts which are considered to be anachronistic to the biblical world, like 'monarchy', 'state', 'class', 'nation', 'religion', et cetera? Only playing with the difference between object language and meta-language does not solve problems. It is true that monotheism is burdened with much trouble because it is rooted in the early modern era and it is also true that the term was coined as a neologism first by Henry Moore in 1660 and was used apologetically to discriminate the Christian anthropomorphic concept of God from the Deistic concept.3 Later, in the 17th century, the term 'polytheism' was added as an oppositional term to 'monotheism'. Following in some way the usage in antiquity (from Tertullian onwards), the term was in the 16th century used synonymously to idolatry (e.g. by Jean Bodin). 'Polytheism' originated in the 1st century CE in Philo's δόξα δ' ή πολύθεος [the honor of a polytheistic doctrine] (Phil. de decalogo 65) and οί πολυθειας έρασταί [the lovers of polytheism] (Phil. de mutatione nominum 205). Philo uses the term polemically to distinguish the non-Jewish religions from the Jewish concept of the First and Second Commandment.4 Contrary to 'monotheism', the term 'polytheism' has some connections to the object language level, but like monotheism, the term is not an endonym or a self-imposed term of any ancient religion in an emic perspective. It is further true that 'polytheism', which was developed against the background of a constructed 'monotheistic faith', was a polemical and apologetic term, also in its Christian usage in modern post-enlightenment times.

However, concepts can be developed further and can be transformed in modern research. Neither has 'monotheism' to denote Moore's concept nor has 'polytheism' to retain the synonymy to idolatry.5 In more recent Religious Studies, the term 'polytheism' is used neutrally to describe religions that conceive of a multiplicity of deities who act for the most part personally in respect to the world. Polytheistic religions are characterised by a structured pantheon which relates deities to each other genealogically, socially or with reference to their competencies. As regards polytheism, the accomplishment of regional, political, social, economical, et cetera integration is very important6 - polytheism is part of a 'professionalisation of religion' and a 'medium of reflection'.7 However, the term and concept keeps the odium of being (a) tributary to 'monotheism'. It remains a 'Tendenzbegriff', as Gregor Ahn has emphasised (Ahn 1993):

'Polytheismus' ist daher ein Tendenzbegriff, eine Form der Beschreibung religionsgeschichtlicher Zusammenhange, die aus einem ausschlieBlich monotheistischen Blickwinkel gewonnen ist und lediglich der Abgrenzung des monotheistischen 'Sonderfalls' aus seinem polytheistischen Umfeld dient, nicht aber darauf abzielt, die für die Anhanger dieser so beschriebenen Religionen ausschlaggebende religiose Wirklichkeit und Welterfahrung zu erfassen. (p. 6)8

Either-nor? The burden of systematisation

An implicit claim of the systematisation of 'religion' is inherent in the diametrical scheme monotheism/polytheism. The scheme pretends to encompass any religion in an either-or-decision: if it is not 'monotheistic', it has to be 'polytheistic' and vice versa. We all know that this binary scheme has caused problems in Religious Studies, because it fails in regard to many particular religions which lack 'theism'. The same holds true for the evolutionary scheme of an original and normative monotheism which later degenerated, and similarly for the assumption of an original animism which developed through a stage of polytheism into the higher, more reflective and similarly normative state of monotheism. In sum, the problems of conceptualising religions as 'monotheistic' are immense: within the history of concepts, monotheism is 'evolutionary', 'lopsided', 'Christian imperialistic', has an 'aesthetical bias' and is for the greater part 'projection' rather than description.

Hacking at the heart: Monotheism and violence

Following Friedrich Nietzsche, Odo Marquard and others linked the birth of modernity to the death of monotheism. Criticism of monotheism as 'monomythic' thinking and the 'praise of polytheism' seemed to form a modern 'pluralistic' alternative way of thinking (Marquard 1989:87-110). In recent debates, monotheism has furthermore become a scapegoat of modernity, as in some way in Peter Sloterdijk's argument (Sloterdijk 2009), for instance. Since David Hume and Arthur Schopenhauer, monotheism has been fraught with the insinuation that it had been responsible for religious violence or that it is even more violent than the more amicable polytheism, because of its inherent claim of exclusive truth. Jan Assmann has fostered the arguments in various publications with his 'Mosaic decision' (Assmann 2009).9 Although this has been refuted by many scholars, and although recently René Bloch has convincingly shown that Jan Assmann's argument perpetuates the apologetic discourse of antiquity (Bloch 2010), the discussion of the connection between monotheism and violence has burdened the concept all over. We may ask whether it is helpful in this situation to abandon the concept of (biblical) monotheism because it is inappropriate. There is likewise an intellectual willingness to offer resistance against the rash dismissal of the concept; or to put it in the metaphoric phrase of Peter L. Berger, when he brands modernity a 'coercion to heresy'(Berger 1992).

Conceptual differentiation as solution or as dissolution?

How can we then hold on to the concept of monotheism in Biblical Studies? There are several strategies which opt for differentiation, risking at the same time to change the concept out of recognition: We may opt for a differentiated use of the prefixes henos and monos to stress aspects of unity, oneness, singularity, singleness, absoluteness and uniqueness. Thus we may differentiate between '[h]eistheism' (a philosophical inclusive monotheism), 'henotheism' (a monotheism that does exclude other divine beings temporarily rather than principally) and 'monotheism' (a religious exclusivity of one single deity), or we can re-establish old terms or coin new, more sophisticated ones like 'kathenotheism', 'monachotheism', 'monotheiotheism' or 'idiomatotheism'. However, this is all the more misleading, as it only conceals the problem. Apart from this, these alternative terms usually do not originate in the object language, but rather in the same philosophical context as 'monotheism' and 'polytheism' do.

One may further differentiate forms of monotheism by using terminological diametrical pairs. Let me name some representative ones: inclusive/exclusive (John Peter Kenney, Klaus Koch, Ernst Axel Knauf, Mark S. Smith et al.); practical/theoretical (Werner H. Schmidt); abstract/concrete (Karl Rahner, Walter Kasper); evolutionary/revolutionary (Jan Assmann); soft/hard (John Dillon); calm/zealous monotheism (Áke V. Ström); particular/universal (Othmar Keel); implicit/explicit (Martin Leuenberger et al.); absolute/ relative (Christoph Auffarth). Without discussing the capability of each proposal, it may be helpful to differentiate the concept of monotheism and thus make it more fluent and dynamic, but it will raise questions whether the 'softer' forms of monotheism, the practical, particular or evolutionary, can be classified as monotheisms or should rather be called henotheism or monolatry.10

The concept of monolatry is most useful, because it avoids the essential or ontological radicalism of 'monotheism'. It denotes temporal or local forms of the veneration of one god without the claim of singleness in the explicit denial of the existence of other gods (Petry 2007:6f.). Monolatry avoids being a theism and is explicitly not monotheism. Thus it is merely meaningful in a polytheistic reference system, which is appropriate for any 'religion' in antiquity. If then 'monolatry' is the more appropriate concept regarding biblical religion, should there still be a future for 'monotheism' in Biblical Studies? Or should we dismiss the concept as a whole?

And the winner is ... : Monotheism as a final good

The problems in applying the concept of 'monotheism' to the religion of Israel/Judah, Yehüd or finally Early Judaism(s) are obvious, and have been multiplied and intensified by the Religionsgeschichtsschreibung [religious historiography] of the last decades. The simple development scheme from polytheism to monotheism through monolatry and 'YHWH alone' is too simple and straightforward. The situation is much more complex than that; we may recall the discussion on the distinctiveness of Israelite religion decades ago, which also fell into the trap of oversimplification. Meanwhile there is now a broad consensus in considering the religion(s) of Israel and Judah as subsets of Syro-Palestinian religions in the first millennium BCE, with a vast amount of common elements and a smaller part of remarkable distinctiveness.11 As 'monotheism' was regarded as being one of the distinctive features, the issue of monotheism was intensively discussed in comparison with the Babylonian (Marduk), Assyrian (Assur), and Syro-Palestinian religions (Baal-Schamem). There are similarities as well as differences, and thus we are left behind again with the problems of conceptualising Israelite or, better, Yehudite religion as 'monotheism'.

Hence, we have to ask ourselves what may get lost if we discard the concept of monotheism in the study of ancient Israelite religion and early Judaism(s). This question is not easy to answer. Possibly we lose or minimise (1) the awareness of the historical dimension of the overall concept 'monotheism', (2) the continuity between the religion of biblical Israel on the one hand and Judaism and Christianity on the other. (3) This will hinder the settlement of the so-called 'Abrahamic ecumene' within a comparative historical framework.12 Finally (4), with the concept of monotheism we may give up a crucial point by which the Old Testament is most relevant in modern discourses.

Be that as it may, the simplifying alternative 'yes/no' or 'useful or not' implies that 'monotheism' is a definite, delineated, solid and within the Forschungsgeschichte [history of research] unchanged concept. As I have shown above, this is not true: the concept has changed radically since its invention by Henry Moore in 1660. Meanwhile, the concept has become a useful tool for biblical scholars in the last 200 years. Yet, some of the struggle with the concept 'monotheism' is rooted in different concepts of God and monotheism in the Bible on the one hand, and systematic reflection on the other hand. The difference was put nicely by Bob Becking (2009):

the living God as witnessed in the various parts of the Hebrew Bible, does not fit very much the systematic construct of a theistic god. The Hebrew resumé makes YHWH a non-candidate for a vacancy in the theistic god department. (p. 10)

To sum up: to get rid of the term and concept is illusory. We cannot really escape 'monotheism', neither as a metalanguage concept (to identify specific kinds of statements in biblical texts), nor as legacy concept in Biblical Studies. Thus we should use in Biblical Studies, even if only to flag the religion of biblical Israel as non-monotheistic.

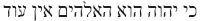

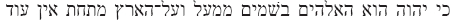

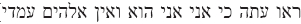

Let me give just one short example from the object language level: 1 Kings 8:60 is a very late verse from King Solomon's prayer:  [that the Lord, he is <the> God; no one else].

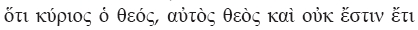

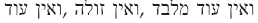

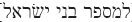

[that the Lord, he is <the> God; no one else].  [God] is no longer an abstract plural here, but has rather become a title or appellative. The LXX makes the title explicit and adds (as many Hebrew manuscripts do) the copulative:

[God] is no longer an abstract plural here, but has rather become a title or appellative. The LXX makes the title explicit and adds (as many Hebrew manuscripts do) the copulative:  [that the Lord, the God, he is <the> God, and there is none beside]. Sven Petry writes (Petry 2007):

[that the Lord, the God, he is <the> God, and there is none beside]. Sven Petry writes (Petry 2007):

In 1Kön 8,60 kommt in jedem Fall ein expliziter Monotheismus zum Ausdruck, denn die bisweilen begegnende Annahme, Dtn 4,35.39 seien noch vor einem polytheistischen Hintergrund zu verstehen und meinten wie das Erste Gebot oder das Schema Dtn 6,4, dass Jhwh der einzige Gott für Israel sei, macht für 1Kön 8,30 keinen Sinn. (p. 94)

The need for categorisations, including different levels of 'monotheism', is clearly shown by Petry's statement.

Monotheism as a differentiated heuristic category

The concept 'monotheism' can be used responsibly as a heuristic category of description on the meta-language level under the following ten premises:

1. 'Monotheism' is a relational rather than an essentialist concept. We always have to define the frame of reference in which it is used. Depending on the context in which we use the concept of monotheism, there are differences in scope and content: as category of the history of religions and the description of the ancient 'religious field', as a category in linguistic contexts to classify types of propositions, in literary historical respect to label certain literary stages such as the 'monotheistic' Deutero-Isaiah against the 'polytheistic' Hosea; or finally within Theology and Religious Studies to define a certain type of religion.

2. The concept aims at description rather than identification of a particular religion. Neither 'monotheism' nor 'polytheism' is a definable type of religion ('Religionstyp') in the religious field in historical perspective. From a historical perspective, 'monotheisms' are rather temporal and/or local phenomena within polytheism.

3. It is not based on any evolutionary, teleological, declining, or depraving scheme. The question whether polytheism or monotheism was first in religious history is an invalid question, because of a category mistake. 'Monotheism' without the opposition of 'polytheism' becomes an empty formula and does not make sense. The concept does not describe global developments in religious history, but rather local, regional and temporal peculiarities (to put it with Gladigow 1997:59, 2002:12: 'insular monotheisms').

4. Monotheism does not necessarily imply the 'singular'. From a religio-historical perspective there may be 'monotheisms', although that does not make sense in a systematic perspective.

5. Monotheism is not diametrically opposed to the concept of polytheism and is not superior in moral respect; polytheism has its own capability in theological, sociological, and historical respect. The term 'polytheism' should no longer be a bugbear or a buzzword in Biblical Studies; that means as a consequence that the Israelite/Judahite religion is not devalued by its historical polytheism. Although a religion cannot be monotheistic and polytheistic at the same time, the contrastive pair monotheism/polytheisms is not understood as encompassing the totality of religions by means of an either-or-process of logical elimination: all religions which are not monotheistic, are not necessarily polytheistic, and vice versa. In Biblical Studies both categories, 'monotheism' and 'polytheism', are more historical than systematic categories. They are applied in intrareligious respect to different phases of development rather than interreligiously to classify in principle the difference between Israelite and other religions.

6. The concept of biblical monotheism is neither inclusivistically coined nor identical with the inclusive philosophical unity-monotheism. Biblical monotheism is not the introduction of a 'true or false distinction' in general (what Assmann addressed as 'Mosaic distinction').13 Biblical monotheism rather aims at a relational truth 'for me' or 'for us' or 'for our salvation'. However, the philosophical and historical dimensions of the concept are in fact neither separated nor by any means identical.14 We must differentiate them carefully and describe the different dimensions properly in Biblical Studies. Taken into other systems of thought (Aussagesysteme), the single conclusion may be different.

7. The ancient biblical statements which we characterise as 'monotheistic' are never meant in an absolute sense. They are etic and not emic and they thus have a limited range within the frame of the ancient Near Eastern world. In all cases in which the relation of YHWH to the other gods is addressed, it is reflected neither theoretically nor systematically.

8. It is very important to keep in mind that the addressee of 'monotheistic' statements in the Bible is Israel or the one who is 'primarily' approached by the texts - not the whole world, the worshipper of other deities or the other gods and goddesses themselves. The scope of the statements is rather directed inwards than projected outwards. Their aim throughout is to convince soteriologically, not philosophically. They are all rather intra- than interreligious statements.

9. The concept of monotheism is complemented by other concepts such as 'exclusivity', 'implicit exclusion', 'explicit uniqueness' et cetera; it is not an absolute, but rather a graded, concept which avoids black and white decisions. Such fuzzy categories such as 'quasi monotheistic' (within a polytheistic frame of reference), 'implicit monotheistic', 'inclusive monotheism', et cetera make sense and can be used to describe various 'degrees' of monotheisms (within and beyond polytheism and monolatry) more properly.

10. The concept is rather useful on the level of single verses, such as statements that make linguistically the uniqueness of one god explicit by excluding other deities. As regards the whole 'religion', which is attested in the Old Testament, the concept is not applicable except - but with less certainty - to a particular time and place (e.g. the official religion in the Persian province Yehüd or Jerusalem from 450 to 350 BCE). Thus the juxtaposition of monotheistic and mythological polytheistic statements in one chapter or one book is not puzzling. On the one hand, these statements do not share the same level of argumentation. On the other hand, the 'degree of monotheism' or 'monotheistic bias' of a text depends on the emphasis which is given to the exclusiveness. Other beings which have absolutely no power over Israel are not existent, but may be addressed in mythological passages.

Monotheism matters: Some paradigmatic examples

The statement given above is a plea for differentiation and for the use of the category 'monotheism' in a contextualised and relational manner. Monotheism matters, but remains a rather limited category of description. Let us look at some of the relevant Old Testament passages to substantiate the differentiation.

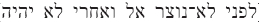

Firstly, phrases such as Isaiah 43:10, 'before me no other god was formed, nor shall there be any after me' [ ], or Isaiah 44:8 'Is there any other god besides me? There is no other rock; I know not one' [

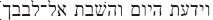

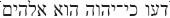

], or Isaiah 44:8 'Is there any other god besides me? There is no other rock; I know not one' [ ], or Deuteronomy 4:39: 'And you shall acknowledge today and take to heart that the Lord, that he is <the> God in the heavens above and on the earth beneath; there is no other' [

], or Deuteronomy 4:39: 'And you shall acknowledge today and take to heart that the Lord, that he is <the> God in the heavens above and on the earth beneath; there is no other' [

] as well as Isaiah 45:18; 46:9 or Deuteronomy 4:35 are monotheistic. They exclude the existence of other powers or 'factors' and their efficacy and significance explicitly. One has to keep in mind that the category of existence is not quite appropriate to Hebrew thinking, which focuses much more on 'acting' than on 'being'. The exclusiveness is expressed linguistically through

] as well as Isaiah 45:18; 46:9 or Deuteronomy 4:35 are monotheistic. They exclude the existence of other powers or 'factors' and their efficacy and significance explicitly. One has to keep in mind that the category of existence is not quite appropriate to Hebrew thinking, which focuses much more on 'acting' than on 'being'. The exclusiveness is expressed linguistically through  [alone, none beside, no other besides], which does not allow other comparable factors, even on the level of language. Simply put: it makes the small <g> god into the big <G> God. The exclusive linguistic phrases tell these verses apart from others which do not have the additional lis fNi [and nothing/nobody else, none beside], et cetera. We may discuss whether Psalm 100:3 'Acknowledge that the Lord, he is God' [

[alone, none beside, no other besides], which does not allow other comparable factors, even on the level of language. Simply put: it makes the small <g> god into the big <G> God. The exclusive linguistic phrases tell these verses apart from others which do not have the additional lis fNi [and nothing/nobody else, none beside], et cetera. We may discuss whether Psalm 100:3 'Acknowledge that the Lord, he is God' [ ] which identifies YHWH in a nominal clause as

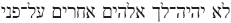

] which identifies YHWH in a nominal clause as  [a god/ God] but - in contrast to Deuteronomy 4:35.39; 7:9; 2 Samuel 7:28; 1 Kings 8:60; 18:24.39; 2 Kings 19:15; Isaiah 37:16; 45:18; 1 Chronicles 17:26; 2 Chronicles 33:13; Ezra 1:3 - spares the article (cf. Jos 2:11; Jr 10:10), belongs to the monotheistic claim, too. The nations which are requested to come to Zion shall acknowledge YHWH, but de facto there is no room for any other god besides. There is but one god, YHWH, who is unique through his acts, especially the election of Israel. To make it clear: These phrases do not classify the 'religion' beyond easily as 'monotheistic', but taken alone these phrases are 'monotheistic' and different from - let us say: monolatric - statements like Deuteronomy 5:7 'you shall have no other gods besides mé[

[a god/ God] but - in contrast to Deuteronomy 4:35.39; 7:9; 2 Samuel 7:28; 1 Kings 8:60; 18:24.39; 2 Kings 19:15; Isaiah 37:16; 45:18; 1 Chronicles 17:26; 2 Chronicles 33:13; Ezra 1:3 - spares the article (cf. Jos 2:11; Jr 10:10), belongs to the monotheistic claim, too. The nations which are requested to come to Zion shall acknowledge YHWH, but de facto there is no room for any other god besides. There is but one god, YHWH, who is unique through his acts, especially the election of Israel. To make it clear: These phrases do not classify the 'religion' beyond easily as 'monotheistic', but taken alone these phrases are 'monotheistic' and different from - let us say: monolatric - statements like Deuteronomy 5:7 'you shall have no other gods besides mé[ ] or Jeremiah 2:28 'because your gods have become as many as your towns, O Judah' [

] or Jeremiah 2:28 'because your gods have become as many as your towns, O Judah' [ ]. These statements differ because they imply a polytheistic background in which other deities are capable to act in principle. This holds true for the attribution of God's jealousy. Addressing YHWH as

]. These statements differ because they imply a polytheistic background in which other deities are capable to act in principle. This holds true for the attribution of God's jealousy. Addressing YHWH as  in Exodus 34:14 (cf. Ex 20:5; Dt 4:24; 5:9; 6:15; 32:16.21) implies at least one rival in law. The marriage metaphor as figure of the covenant and the

in Exodus 34:14 (cf. Ex 20:5; Dt 4:24; 5:9; 6:15; 32:16.21) implies at least one rival in law. The marriage metaphor as figure of the covenant and the  [whoring after] as accusation of adultery makes clear that there are serious rivals. Jealousy becomes hollow without competition; thus, speaking of God's jealousy implies the possible existence of other deities.

[whoring after] as accusation of adultery makes clear that there are serious rivals. Jealousy becomes hollow without competition; thus, speaking of God's jealousy implies the possible existence of other deities.

Secondly, the categories become sometimes blurred, as for instance in Deuteronomy 10:17: 'for the Lord, your God, he is the God of gods and the Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome' [

] and other formulae of incomparability (cf. Rechenmacher 2010). There are 'other gods' which are subordinated in a pantheon, a structure which sounds polytheistic - in other words is linguistically not monotheistic - but the superiority and dignity of YHWH is so paramount that there is no room left for other deities. The difference is - as in Deutero-Isaiah - categorial between creator and creature, master and slave, king and subject et cetera Deuteronomy 10:17 is implicitly monotheistic - YHWH is in fact the only sample of the generic group. One may call this 'monolatry' by principle, with the position of YHWH as not the primus inter pares within a pantheon, but rather as the only one that fits the criteria of sovereignty at all. This seems to be the basic assumption in the polemic texts which address a competition of deities ad intra. Considering YHWH as the one God which has absolute sovereignty fits for Psalm 96:4-5:

] and other formulae of incomparability (cf. Rechenmacher 2010). There are 'other gods' which are subordinated in a pantheon, a structure which sounds polytheistic - in other words is linguistically not monotheistic - but the superiority and dignity of YHWH is so paramount that there is no room left for other deities. The difference is - as in Deutero-Isaiah - categorial between creator and creature, master and slave, king and subject et cetera Deuteronomy 10:17 is implicitly monotheistic - YHWH is in fact the only sample of the generic group. One may call this 'monolatry' by principle, with the position of YHWH as not the primus inter pares within a pantheon, but rather as the only one that fits the criteria of sovereignty at all. This seems to be the basic assumption in the polemic texts which address a competition of deities ad intra. Considering YHWH as the one God which has absolute sovereignty fits for Psalm 96:4-5:

For great is the Lord, and greatly to be praised; he is to be revered above all gods. For all the gods of the peoples are idols [

], but the Lord made the heavens.

Whilst the gods of the nations are worthless idols - or as the LXX calls them, δαιµόνια [demons i.e. heathen gods] - YHWH is creator of the heavens. There is no real comparability: cosmic power and efficacy stand against inefficacy that is merely materiality. This is - as it has been called above - implicit monotheism or 'mocking monotheism' in the linguistic garment of polytheism and image criticism.15 Although the gods of the nations are focused explicitly, one has to keep in mind that the polemic is addressed inwards (v. 10).

Thirdly, I would suggest adding the category of implicitness to the explicit exclusivity claim. I will use this category in a more comprehensive manner and slightly differently to previous suggestions in a threefold way (see below). Often in Biblical Studies the term 'implicit monotheism' denotes the monotheism of the priestly code or the book of Job, in which the denial of other deities is contextually missing and where no other deities occur.16 'Monotheism' forms the background and seems to be evident. The form of 'implicitness' described above is different: propositions which are polytheistic on the linguistic surface are determined de facto by the monotheistic conviction that there is no other god (Petry 2007:9). This form of implicitness is often recognisable in the context of idol criticism. Thus we may speak of implicit monotheism in Ezekiel and Jeremiah in those parts of the books, in which other beings with supposed divinity (or the beings formerly known as gods) are mentioned but have neither power nor any sovereignty. They are by no means comparable to YHWH. If Ezekiel addresses the other gods as  [abominables, monsters, abhorrent ones] and

[abominables, monsters, abhorrent ones] and  [dung, shit or crappy ones], these designations are mockery and sarcasm, which leaves not much room for existence, efficacy or realness of these materialised entities. They are objects rather than gods. The 'gods' are narrowed to their images and 'exist' merely materially. The same holds true for

[dung, shit or crappy ones], these designations are mockery and sarcasm, which leaves not much room for existence, efficacy or realness of these materialised entities. They are objects rather than gods. The 'gods' are narrowed to their images and 'exist' merely materially. The same holds true for  [vanity, wind, things that do not exist] in Jeremiah 2:5 (cf. Jr 8:19; 14:22; 16:19 and 10:8.15; 51:18),

[vanity, wind, things that do not exist] in Jeremiah 2:5 (cf. Jr 8:19; 14:22; 16:19 and 10:8.15; 51:18),  [lie, breach of faith] in Jeremiah 16:19 (cf. Jr 13:25; 10:14; 51:17) and

[lie, breach of faith] in Jeremiah 16:19 (cf. Jr 13:25; 10:14; 51:17) and  [deception, lie] in Jeremiah 18:15 (cf. Jr 2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 46:11).

[deception, lie] in Jeremiah 18:15 (cf. Jr 2:30; 4:30; 6:29; 46:11).

On the one hand, these statements are comprehensible only within a polytheistic frame of reference, which takes the existence of other deities into account, but on the other hand these deities are ineffective and thus inexistent. I would like to call this 'intolerant monolatry', where others speak of 'implicit monotheism' here, too. There is undoubtedly a form of implicitness, but in my view 'implicit monotheism' is a rather generic category which encompasses different forms of monotheisms:

• the implicitness of not naming other gods. The expressions emphasise the exclusivity of one God instead; they do not use explicit linguistic means to express that there exists only the one God (monotheism as implication, e.g. the priestly code)

• the implicitness of a silent self-evident concentration of one god, taking the uniqueness for granted rather than addressing it (implicit monotheism)

• the implicitness described above, in which the polemic against other deities is so strong that their existence is totally diminished (implicit exclusion).

Lastly, it is quite difficult to draw the boundaries sharply and often we have to consider the context of these statements. This can be justified in Deuteronomy 32. Again we cannot go into details here, but only look at the limits of the monotheistic-polytheistic dichotomy: At first glance Deuteronomy 32:16 'they made him jealous with strangers; with abhorrent things they provoked him' [ ] seems to fit in the incomparability-section, but the context of the post-exilic chapter of Deuteronomy makes it much more 'monotheistic'. Although the general date of a text is a criterion which is beyond textual observations and must not form the only argument, the context here colours the statement as more or less monotheistic. Beginning with the universality of verse 1 and the reflection of the creator who acts in history in the following verses, there is not room for much besides YHWH. Jeshurun has abandoned his creator (Dt 32:15

] seems to fit in the incomparability-section, but the context of the post-exilic chapter of Deuteronomy makes it much more 'monotheistic'. Although the general date of a text is a criterion which is beyond textual observations and must not form the only argument, the context here colours the statement as more or less monotheistic. Beginning with the universality of verse 1 and the reflection of the creator who acts in history in the following verses, there is not room for much besides YHWH. Jeshurun has abandoned his creator (Dt 32:15  [he abandoned the God who made him]) and 'stirred him to jealousy with strangers or strange ones' [

[he abandoned the God who made him]) and 'stirred him to jealousy with strangers or strange ones' [ ]. To identify the

]. To identify the  [foreigners, strange ones] with 'foreigners' is less probable, not only because of Deuteronomy 32:15, but especially because of Deuteronomy 32:17: 'They sacrificed to demons which were no gods, to gods they had never known, to new ones, who came but lately, whom your fathers had never feared' [

[foreigners, strange ones] with 'foreigners' is less probable, not only because of Deuteronomy 32:15, but especially because of Deuteronomy 32:17: 'They sacrificed to demons which were no gods, to gods they had never known, to new ones, who came but lately, whom your fathers had never feared' [

].17 Strikingly, the sacrifices are not addressed to

].17 Strikingly, the sacrifices are not addressed to  [other gods] but to demons, which are no divine beings. Demons become prominent precisely in later post-exilic texts, such as Psalm 106:37; Isaiah 13:21; 34:14 et cetera.18 This is by no means at random, but rather a tendency that the 'gods' made way for the 'demons'. These beings are not deities,

[other gods] but to demons, which are no divine beings. Demons become prominent precisely in later post-exilic texts, such as Psalm 106:37; Isaiah 13:21; 34:14 et cetera.18 This is by no means at random, but rather a tendency that the 'gods' made way for the 'demons'. These beings are not deities,  [no deities, no gods] although they are called

[no deities, no gods] although they are called  [gods or divine beings], which were not known by the fathers. The denial of divineness implies a monotheistic claim in a polytheistic robe. The same holds true for Deuteronomy 32:21: although the monolatric concept of jealousy is used, the zeal of YHWH is directed against

[gods or divine beings], which were not known by the fathers. The denial of divineness implies a monotheistic claim in a polytheistic robe. The same holds true for Deuteronomy 32:21: although the monolatric concept of jealousy is used, the zeal of YHWH is directed against  [the 'no gods'] and

[the 'no gods'] and  ['vanities', 'nothings'] rather than against rivals. As in Deuteronomy 32:15-17, the case is not for diachrony but rather for a blend of linguistically explicit and implicit monotheism. Taken together, Deuteronomy 32:15-17.21 seems just a little further on the way to explicit monotheism than the implicit monotheism in Jeremiah and Ezekiel: YHWH is the only one, in efficacy and thus in existence. Most explicit in denying the existence and efficacy of other deities, or to put it more bluntly, most 'monotheistic' in Deuteronomy 32 is the subtle and keen verse 39: 'See now, that I, yes I am he, and there is no god beside me' [

['vanities', 'nothings'] rather than against rivals. As in Deuteronomy 32:15-17, the case is not for diachrony but rather for a blend of linguistically explicit and implicit monotheism. Taken together, Deuteronomy 32:15-17.21 seems just a little further on the way to explicit monotheism than the implicit monotheism in Jeremiah and Ezekiel: YHWH is the only one, in efficacy and thus in existence. Most explicit in denying the existence and efficacy of other deities, or to put it more bluntly, most 'monotheistic' in Deuteronomy 32 is the subtle and keen verse 39: 'See now, that I, yes I am he, and there is no god beside me' [ ]. The more or less explicit tendency of denying the existence of other divine beings in Deuteronomy 32 - which has its strongest parallel in Deutero-Isaiah (Is 43:10; 46:4)19 - has an impact on the understanding of the crucial verse Deuteronomy 32:8, where the 'Most High' set up the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the children of Israel [

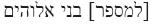

]. The more or less explicit tendency of denying the existence of other divine beings in Deuteronomy 32 - which has its strongest parallel in Deutero-Isaiah (Is 43:10; 46:4)19 - has an impact on the understanding of the crucial verse Deuteronomy 32:8, where the 'Most High' set up the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the children of Israel [ ]. Thus Deuteronomy 32:8 cannot be regarded as a 'polytheistic window', as Konrad Schmid nicely and disparagingly has put the 'atavism'. However, the Qumran Manuscript 4QDtnJ20 has, as is generally known,

]. Thus Deuteronomy 32:8 cannot be regarded as a 'polytheistic window', as Konrad Schmid nicely and disparagingly has put the 'atavism'. However, the Qumran Manuscript 4QDtnJ20 has, as is generally known,  [according to the number of the sons of god] and the LXX reads

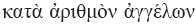

[according to the number of the sons of god] and the LXX reads

[according to the number of angels of God]. Attention to this point in the history of research has been consistently great and one may consider for example with Manfred Weippert the originality of the

[according to the number of angels of God]. Attention to this point in the history of research has been consistently great and one may consider for example with Manfred Weippert the originality of the  [sons of god] - reading, which is attested by the translation of the LXX (Weippert 1997:5). Nevertheless, as Konrad Schmid has convincingly shown (Schmid 2006), there is no polytheistic atavism in the

[sons of god] - reading, which is attested by the translation of the LXX (Weippert 1997:5). Nevertheless, as Konrad Schmid has convincingly shown (Schmid 2006), there is no polytheistic atavism in the  [sons of god] and it is most probable that YHWH has to be identified with

[sons of god] and it is most probable that YHWH has to be identified with  [the Most High, Elyon], the most high. If this is correct, Deuteronomy 32:8 shows the same tendency as the other examples from Deuteronomy 32 the background is 'monotheistic', but the chapter rather positions itself linguistically and conceptually in polytheistic terms. Thus, one has to discuss every single passage within its contextual framework and sometimes it is not easy to judge between an older polytheistic framework and an implicit background monotheism, which uses mythological language.

[the Most High, Elyon], the most high. If this is correct, Deuteronomy 32:8 shows the same tendency as the other examples from Deuteronomy 32 the background is 'monotheistic', but the chapter rather positions itself linguistically and conceptually in polytheistic terms. Thus, one has to discuss every single passage within its contextual framework and sometimes it is not easy to judge between an older polytheistic framework and an implicit background monotheism, which uses mythological language.

These examples make it quite clear that monotheism in Biblical Studies has its value far beyond numerical singularity.

Conclusion

In the first part of this article we have collected serious objections against the concept of monotheism. We asked whether the ambiguity and the problem discredit the concept of monotheism as inappropriate for Biblical Studies, or whether it calls for differentiation. In the following argument it was indicated that the concept is useful to describe certain stages of the conceptual and linguistic development of Israelite religion. Both term and concept of monotheism in Biblical Studies are necessary, but not sufficient, if we want to reconstruct the religious history of Israel, Judah, Yehüd and Early Judaism(s). Especially useful is to describe the (biblical) statements accurately; we proposed categories such as implicit monotheism, intolerant monolatry, implicit exclusion, explicit uniqueness, monotheism as implication et cetera. In so doing the category of monotheism can be useful as heuristic and relational category.

Anybody who considers the concept of monotheism as being so problematic that we should discard it has to designate terminological and conceptual alternatives (Heiser 2008:27). As long as we have none, the concept is heuristically valuable (Leuenberger 2010:10; Keel 2007:21). However, it remains limited: To ask whether the book of Deuteronomy, or any other biblical book, is monotheistic, is in my view not appropriate. It asks for applying a category to a textual world, which can employ monotheism only on a linguistic level. Strictly spoken, there is no monotheistic book in the Old Testament. Either there are no monotheism-like assertions which make the uniqueness explicit by excluding other deities or forces (e.g. in the book of Haggai), or these statements are flanked by polytheistic, mythological, et cetera. statements, which imply at least a plurality of divine beings. Thus, to call the Hebrew Bible monotheistic is to provide only half of the story.21 The question whether the Israelite, Judahite or Yehudite religion was monotheistic at a certain stage, may also be an invalid question. At any rate, the answer cannot be given from the textual world of the Bible, which might be in some particular parts monotheistic. Thus, as I have shown, in my view the concept of monotheism should have and will have a future in Biblical Studies, whether we dismiss it or not. We should discuss it, define it, disambiguate it, disburden it, but we should not discard it.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Ahn, G., 1993, 'Monotheismus - Polytheismus', in M. Dietrich & O. Loretz (eds.), Mesopotamica - Ugaritica - Biblica, pp. 1-24, Butzon & Bercker, Kevelaer. [ Links ]

Ahn, G., 2003, 'Monotheismus und Polytheismus als religionswissenschaftliche Kategorie?', in M. Oeming & K. Schmid (eds.), Der eine Gott und die Götter, pp. 1-10, Theologischer Verlag, Zurich. [ Links ]

Assmann, J., 2009, The Price of Monotheism, Stanford University Press, Stanford. [ Links ]

Auffarth, C., 1993, 'Henotheismus/Monolatrie', in H. Cancik, B. Gladigow & M.S. Laubscher (eds.), Handbuch religionswissenschaftlicher Grundbegriffe, pp. 104-105, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Becking, B., 2009, 'The Boundaries of Israelite Monotheism', in A.-M. Korte & M. de Haardt (eds.), The Boundaries of Monotheism, pp. 9-27, Brill, Leiden. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004173163.i-250.5 [ Links ]

Berger, P.L., 1992, Der Zwang zur Haresie, Herder Verlag, Freiburg. [ Links ]

Bloch, R., 2010, 'Polytheismus und Monotheismus in der Antike', in R. Bloch, S. Häberli & R.C. Schwinges (eds.), Fremdbilder-Selbstbilder, pp. 5-24, Schwabe Verlag, Basel. [ Links ]

Coogan, M.D., 1987, 'Canaanite Religions and Lineage', in P.D. Miller, P.D. Hanson & S.D. Mc Bride (eds.), Ancient Israelite Religion, pp. 115-124, Fortress Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Frevel, C., 2007, 'Einer für alle?', in R. Althaus, K. Lüdicke & M. Pulte (eds.), Kirchenrecht und Theologie im Leben der Kirche, pp. 503-524, Ludgerus Verlag, Essen. [ Links ]

Frey-Anthes, H., 2007, Unheilsmachte undSchutzgenien, Antiwesen und Grenzganger, Academic Press Fribourg, Fribourg. [ Links ]

Gladigow, B., 1997, 'Polytheismus' [Polytheism], Zeitschrift für Religionswissenschaft 5, 59-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/0026.59 [ Links ]

Gladigow, B., 2002, 'Polytheismus und Monotheismus', in M. Krebernik & J. van Oorschot (eds.), Polytheismus und Monotheismus in den Religionen des Vorderen Orients, pp. 3-20, Ugarit-Verlag, Munster. [ Links ]

Hayman, P., 1991, 'Monotheism - A Misused Word in Jewish Studies?', Journal of Jewish Studies 42(2), 1-15. [ Links ]

Heiser, M.S., 2008, 'Monotheism, Polytheism, Monolatry, or Henotheism?', Bulletin for Biblical Research 18(1), 1-30. Hess, R.D., 2007, Israelite Religions, Baker, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Hülsewiesche, R., 1984, 'Monotheismus II', in J. Ritter, K. Gründer & G. Gabriel (eds.), Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie, vol. 6, pp. 142-146, Schwabe Verlag, Basel. [ Links ]

Keel, O., 2007, Die Geschichte Jerusalems und die Entstehung des Monotheismus, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Keiser, T., 2005, 'The Song of Moses: A Basis for Isaiah's Prophecy', Vetus Testamentum 55, 486-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853305774651923 [ Links ]

Lanczkowski, G., 1989, 'Polytheismus', in J. Ritter, K. Gründer & G. Gabriel (eds.), Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie, vol. 7, p. 1087, Schwabe Verlag, Basel. [ Links ]

Leuenberger, M., 2010, Ich bin Jhwh und keiner sonst. Der exklusive Monotheismus des Kyros-Orakels Jes 45,1-7, Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

MacDonald, N., 2003, Deuteronomy and the Meaning of Monotheism, Mohr, Tübingen. [ Links ]

MacDonald, N., 2004, 'The Origin of Monotheism', in L.T. Stuckenbruck & W.E. North (eds.), Early Jewish and Christian Monotheism, pp. 204-215, T & T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Marquard, O., 1989, 'In Praise of Polytheism', in O. Marquard (ed.), Farewell to Matters of Principle, pp. 87-110, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Moberly, R.W.L., 2004, 'How appropriate is "monotheism" as a category for biblical interpretation?', in L.T. Stuckenbruck & W.E. North (eds.), Early Jewish and Christian Monotheism, pp. 216-234, T & T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Peri, C., 2005, 'The Construction of Biblical Monotheism', Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 19, 135-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09018320510032484 [ Links ]

Petry, S., 2007, Die Entgrenzung JHWHs: Monolatrie, Bilderverbot und Monotheismus im Deuteronomium, in Deuterojesaja und im Ezechielbuch, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Rechenmacher, H., 2010, 'Unvergleichlichkeit und Ausschlietëlichkeit Jahwes', in C. Diller, K. Olason & R. Rothenbusch (eds.), Studien zu Psalmen und Propheten, pp. 237-250, Herder Verlag, Freiburg. [ Links ]

Sloterdijk, P., 2009, God's Zeal, Polity Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Schmidt, W.H. & Graupner, A. & Delkurt, H., 1993, Die Zehn Gebote im Rahmen alttestamentlicher Ethik, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt. [ Links ]

Schmid, K., 2003, 'Differenzierungen und Konzeptualisierungen der Einheit Gottes in der Religions- und Literaturgeschichte Israels', in M. Oeming & K. Schmid, Der eine Gott und die Götter, pp. 11-38, Theologischer Verlag, Zürich. [ Links ]

Schmid, K., 2006, 'Gibt es "Reste hebráischen Heidentums" im Alten Testament?', in A. Wagner (ed.), Primare und sekundare Religion als Kategorie der Religionsgeschichte des Alten Testaments, pp. 105-120, de Gruyter, Berlin. [ Links ]

Smith, M.S., 2010, God in translation. Deities in cross-cultural discourse in the Biblical world. Second edition, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Stolz, F., 1996, Einführung in den biblischen Monotheismus, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt. [ Links ]

Taschner, J., 2007, 'Dieses Lied wird seinen Nachkommen nicht aus dem Kopf gehen. Dt 31:21)', in G. Steins & E. Ballhorn (eds.), Der Bibelkanon in der Bibelauslegung, pp. 189-197, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Weippert, M., 1997, Jahwe und die anderen Götter. Studien zur Religionsgeschichte des antiken Israel in ihrem syrisch-palastinischen Kontext, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. [ Links ]

Zenger, E., 1994, 'Das Weltenkönigtum des Gottes Israels (Ps 90-106)', in N. Lohfink & E. Zenger (eds.), Der Gott Israels und die Völker. Untersuchungen zum Jesajabuch und zu den Psalmen, pp. 151-178, Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Christian Frevel

Lehrstuhl für Altes Testament

Katholisch-Theologische Fakultát

Gebáude GA, Etage 7, Raum 149, Universitátsstr

150, D-44780 Bochum

Email: christian.frevel@rub.de

Received: 29 Oct. 2012

Accepted: 21 Mar. 2013

Published: 20 Sept. 2013

1.Ahn (2003:9) and already Ahn (1993:1-24).

2.I would like to thank the Kate Hamburger Kolleg at the Ruhr-Universitát Bochum who provided me with many opportunities to deal with the topic of monotheism in religious studies and supported my own focus on this subject.

3.For the history of the term 'monotheism', see Hülsewiesche (1984:142-146); Assmann (2009:31-35); MacDonald (2003, 2004).

4.See further Lanczkowski (1989:1087).

5.See the famous polemic of Y. Amit in her review on Nathan MacDonald: 'The argument that the biblical concept of monotheism differs from later use of the same term reminds me of the argument that modern democracy differs from ancient Greek democracy. No one expects these concepts to be identical. Terms and concepts change through the ages, and although biblical morality is unlike modern Western morality, it does not mean that there was no morality in ancient Israel' (Review of Biblical Literature 7/2005 http://www.bookreviews.org, July 5th 2012).

6.Cf. Gladigow (1997:62).

7.Gladigow (2002:10-11). Polytheistic religions do not exclude but may even integrate 'insular monotheisms', as Gladigow calls it.

8.Regarding the Christian bias which associates the term with immorality and sin, see Gladigow (1997:60); Gladigow (2002:5).

9.There is a broad discussion of Assmann's book(s); see for example my essay Frevel (2007).

10.For the use of these terms see Auffarth (1993). Sometimes the concept of monolatry is called 'inclusive monotheism' (e.g. Smith 2010:165).

11.See in the beginning of the debate Coogan (1987:115) and recently Hess (2007:14f.).

12.See Stolz (1996:14): 'Wenn die Vergleichbarkeit nicht mehr durch einfache Begriffe expliziert werden kann, so hat dies in einer komplexeren Weise zu geschehen. Verzichtet man völlig auf die Explikation des Vergleichsinstrumentariums, so werden unkontrollierbare Vergleichsmechanismen wirksam.'

13.Just besides: in my view the greatest trouble in the Assmann-debate is the permutation of categories: truth vs. efficacy/salvation, incomparableness vs. singleness, memory vs. history, interreligious vs. intrareligious et cetera.

14.Rechenmacher goes in the same direction but oversteps the mark: 'Der theoretische Aspekt steht also nicht in Konkurrenz zum soteriologischen, sondern ist dessen unverzichtbares Teilmoment' (Rechenmacher 2010:244).

15.It does not matter here whether Psalm 96 is an addition to the first exilic composition of the YHWH-kingship psalms (Zenger 1994) or part of an original later composition.

16.See for instance Schmidt, Graupner and Delkurt (1993:44).

17.The verb  III which is translated from the οίδα in LXX is used only in Deuteronomy 32:17 and sounds like

III which is translated from the οίδα in LXX is used only in Deuteronomy 32:17 and sounds like  , the goat-demons or satyrs (Lv 17:7; 2 Chr 11:15; Is 34:14), which changes the tenor into a harsh polemic against the fathers.

, the goat-demons or satyrs (Lv 17:7; 2 Chr 11:15; Is 34:14), which changes the tenor into a harsh polemic against the fathers.

18.See the additional evidence from the LXX Psalm 90:6; 96:5; Isaiah 13:21; 34:14; 65:3; Bar 4:7.35 and most prominently the Book of Tobit (Frey-Anthes 2007).

19.See Taschner (2007:192) who identifies much more textual parallels, though not all of them are convincing, for example Deuteronomy 32:8-9 shall parallel Isaiah 42:6-7. Taschner labels Deuteronomy 32 as 'Kompendium der Schriftprophetie' (192); Keiser (2005:488-489).

20.DJD XIV, 90 with plate XXIII, Frg. 34.

21.See (especially the latter part of the quotation) Peri (2005:139): 'The Old Testament is in fact the first document of Jewish monotheism, or, more properly, the first attested act of the building of Jewish monotheism.'