Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versão impressa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.24 Cape Town 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v24i0.1109

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A conceptual framework to guide public oral health planning in Limpopo province

Lawrence Thema; Shenuka Singh

Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: There is limited understanding of the complexities surrounding public oral health service delivery in South Africa and the resulting impact on oral health outcomes.

AIM: This study aimed to identify the strengths and challenges in oral health decision-making within the public health sector and to propose a conceptual framework to guide oral health service delivery in the province.

SETTING: This study was performed in the Limpopo province.

METHODS: National and provincial health policy documents were reviewed to identify statements on oral health service delivery. A face-to-face, semi-structured interview was conducted with the Limpopo Provincial Manager of Department of Health, Oral Health Services. Data were collected on oral health policies and the organisational structure of public oral health services. A self-administered questionnaire was completed by five district managers of public oral health services to obtain data on the delivery of public oral health services in Limpopo province.

RESULTS: The results indicated that oral healthcare was not explicitly mentioned, included or referred to in the examined health policy documents. The interviews indicated that public oral health services do not have a dedicated budget and were not considered a priority. The questionnaire results revealed challenges in infrastructure, human resources and perceived marginalisation from the healthcare services. Participants agreed that there was a need for oral health to be clearly expressed and prioritised in health policy statements.

CONCLUSION: This study proposed a framework that incorporated the identified core components that influenced oral health services provision in Limpopo province.

Keywords: Oral health; Policy; Priority; Budget; Incorporation; Integration.

Introduction

Background

Despite the provision of free public oral health services in primary healthcare facilities within the Department of Health in Limpopo Province, South Africa (Department of Health 2015), common oral diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal disease, continue to impact the general health of individuals (Van Wyk & Van Wyk 2004). The oral health implications of communicable and non-communicable diseases are well documented, the resulting effect being an increased burden on public health services (Petersen 2008). The underlying determinants of ill health, such as malnutrition, unsafe drinking water, inadequate sanitation and exposure to infectious diseases, may further increase risk in contracting oro-facial-related diseases (Peterson 2008).

The Limpopo Provincial Health Department has made concerted efforts through policy and planning endeavours to improve oral health services, and there is commitment to ensure the availability of health services that are closely located to the communities served (Department of Health 2015); however, many challenges still exist. Oral health services remain largely located in urban areas with a focus on mainly curative services, such as dental fillings and extraction of teeth (Department of Health 2015).

While the Limpopo Province Oral Health Transformation Plan (2014-2019) recommended that prevention and management of common oral diseases in Limpopo province require an adequate number of oral health professionals in relation to the target population, there is little documented evidence of translation into practice (Singh, Myburgh & Lalloo 2010). The plan (2014-2019) also highlighted significant shortages and variation in the geographic distribution of oral health professionals and the availability of proper functioning dental facilities in the province. The lack of appropriate workforce and skills mix places further strain on under-resourced services (Singh et al. 2010).

This study therefore aimed to establish the extent to which public oral health services are expressed in selected national and provincial policy documents, and consequently implemented at provincial and district levels. The study also aimed to propose a conceptual framework to guide policy planning and development.

Methods

This was a descriptive and exploratory study, conducted in all five districts of Limpopo province (Capricorn, Mopani, Sekhukhune, Vhembe and Waterberg). Data collection included oral health policy document review, semi-structured interviews with the provincial and district managers of public oral health services in Limpopo province, and a self-administered questionnaire for the latter.

Policy documents related to oral healthcare were retrieved from the National and Limpopo Department of Health's websites. Policy documents examined included the National Health Act (Act 61 of 2003), Provincial Health Strategic Plan (2013/2014), Provincial Annual Performance Plan (2013/2014), Limpopo Province Oral Health Transformation Plan (2014-2019) and South African National Oral Health Strategy (2010). The districts were coded as follows: Capricorn - A, Mopani - B, Sekhukhune - C, Vhembe - D and Waterberg - E. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in writing before commencing the study, and issues of data security, confidentiality and privacy were maintained. Each document was reviewed to establish the nature and extent of any reference to oral health services.

A semi-structured interview was conducted with the Manager of Oral Health Services in the Provincial Department of Health, Oral Health Services to gain better understanding of provincial oral health policy development and implementation. The interview schedule focused on the following areas: existence of a provincial oral health policy or plan; monitoring of oral health policy implementation; strengths and limitations of the current oral health services; and recommendations for improving the provincial oral health services in Limpopo.

A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from the five district managers responsible for coordination of oral health service delivery in the identified districts. The questionnaire included questions on institutional support for oral health, organisational structure of oral health services and service delivery. The questionnaire made use of a Likert scale format that included scales ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5.

A follow-up, semi-structured interview was held with each district manager after the questionnaire was completed to gain better understanding of their perspectives on oral health service delivery. The interview schedule focused on priority of oral health programmes in the district; existence of policy guidelines for oral health service delivery at district level; monitoring and evaluation of policy guidelines; availability of resources for oral health service delivery; strengths and challenges of oral health service delivery; and recommendations for improved oral health services. All interviews were digitally recorded once permission was obtained from each participant.

Data collection and analysis

The policy documents were analysed using content analysis.

Data from the questionnaire were analysed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Foster City, CA). The responses to the open-ended questions were grouped, and emergent themes were examined and compared for possible associations.

The data from the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the narratives for each interview were organised and examined for emergent themes (Braun & Clarke 2006). Each compiled narrative was sent to the respective respondent to verify the accuracy of the recorded information, and participants also had an opportunity to comment on the analysed data.

Validity and reliability

A pilot study was conducted with 10% of participants (not used in the study) to review and refine the questions posed in the questionnaire. The research proposal and the research instrument was also reviewed by a peer-review panel located within the institution where the researchers are based. Content validity was maintained by ensuring that the domains of the questionnaire were relevant to the study population's work responsibilities and interests.

Reliability of the data was determined by ensuring that the data was double-checked during data entry and all outliers were corrected. Internal validity was maintained by ensuring a logical structure in the research report with clearly defined methods to execute the study. External validity focused on the generalizability of the study findings.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BREC REF: 327/14), and approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Department of Health in Limpopo Province.

Results

The extent to which oral healthcare is expressed in national and provincial policy documents is presented in Table 1. The National Health Act made no reference to oral health.

The results of the interview with the Provincial Manager of Oral Health Services revealed challenges in the implementation and monitoring of oral health policy in Limpopo province (Table 2). The provincial manager indicated a disconnect between national and provincial oral health planning, where 'national promises to assist us to amend our provincial one; we are creating our own and the province has its own standardization; so it becomes a challenge' (Provincial manager).

The results from the questionnaire indicated that district managers were having challenges for oral health service delivery due to a lack of 'provincial oral health policy' (Table 3). Other challenges included 'no dedicated oral health budget, challenging procurement for basic consumables and repair and service of equipment' (Participants A, B, C, D and E). In the follow-up interview, district managers identified the following challenges: oral health being low on the policy agenda, lack of dedicated budget for oral health services and poor infrastructure for oral health services (including mobile oral health services) (Participants A, B, C, D and E).

Discussion

This study examined the possible impact of policy, and its implementation (and lack thereof) at various levels of oral service provision in Limpopo province. The study also identified the specific levels (national, provincial and district) at which strengths and challenges of oral healthcare were indicated.

Policy

Overall document analysis indicated that oral health expressions or statements are not uniformly included in the identified health policy documents. The results suggested a non-prioritisation of oral health, lack of implemented oral health policy and lack of dedicated budget for oral health. The provincial manager indicated that the provincial oral health policy was still in draft form. This reported lack of formalised oral health policy or uniform policy guidelines implied that communities in Limpopo province could be disadvantaged in accessing equitable oral health services. This finding is consistent with Singh et al. (2010), who also reported that oral health policy, planning and implementation were not consistent in all provinces in South Africa. The results further suggested that oral health service delivery in Limpopo province was not integrated with other key health services. This disadvantages oral health services not only by its exclusion from policy documentation, but through alienation from health teams' joint activities (Thema & Singh 2013).

Strategic planning

The findings of the present study support those of Singh et al. (2010), which revealed limited communication, collaboration or partnership in planning for primary healthcare and implementing healthcare practice (Singh et al. 2010). Effective partnership development and collaborative efforts in oral health should avoid duplication of services and promote increased access to care (AACDP 2010; Santa Fe Group 2008; Sheiham 2005). The study findings also support other studies that front-line primary healthcare professionals (namely, community nurses, community medical doctors and their assistants) should prioritise vulnerable and underserved communities (Sheiham 2005; Thema & Singh 2013). Primary healthcare professionals could be instrumental in providing screening services for oral diseases, and strategies could include the incorporation of oral health education into the day-to-day service provision. This, however, can only be possible, if there is regular and ongoing in-service training for health professionals to better equip them with skills in identifying and referring patients or clients with oral conditions (OHCC 2014; Sheiham 2005). The envisaged inter-professional collaborative practice would increase the number of healthcare settings that provide oral healthcare in health centres (Thema & Singh 2013). Oral health professionals have the opportunity to detect chronic conditions that share risk factors with oral diseases, specifically hypertension and diabetes, while providing oral healthcare (AACDP 2006; OHCC 2014).

Budget

The results indicated that the lack of dedicated budget negatively impacts oral healthcare. This finding is consistent with other studies examining oral health service in Limpopo province (Thema & Singh 2017). Limited resources have a wide-ranging negative impact on health services in both developing and developed countries (AACDP 2010; Mejia et al. 2008; USDoHHS 2014). Similarly, lack of dedicated budget was also observed in Hispanic communities, which resulted in limited infrastructure, fewer professionals, limited consumables, and limited transport and maintenance for mobile oral health services (Mejia et al. 2008). By South African standards, lack of dedicated budget ultimately results in violation of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Batho Pele Principles and the South African Patient's Charter of 1999, which collectively advocate individual rights to healthcare.

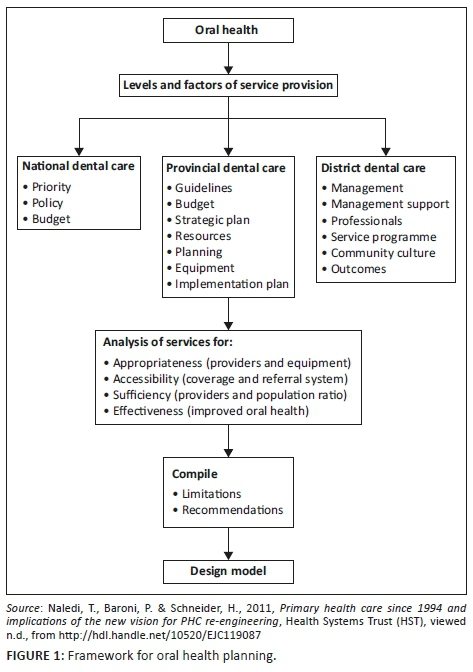

Noting the current challenges with oral planning in the province, the following framework is proposed to guide policy monitoring and review. This framework comprises the following components: prioritisation of oral health, the role of policy, budgetary allocations, need for strategic planning and organisation within health services, and collaboration and support from management. These identified components are similar to other frameworks developed for vulnerable populations in developing countries and underserved communities (AACDP 2006; Bhayat & Cleaton-Jones 2003; Magnussen, Ehiri & Jolly 2004; OHCC 2014; Petersen 2008).

The proposed framework for oral health planning

The framework described below focuses on the levels of provision of oral healthcare, aspects that determine and influence the status of services, and their relationship in impacting public oral health services provision in Limpopo province (Ngulube, Mathipa & Gumbo 2015). The determinants of public oral health services provision in Limpopo province may be categorised into groups emanating from different levels of government services provision. Their responsibilities, which include appropriate, accessible and effective services, are highlighted within Figure 1 (Naledi, Baroni & Schneider 2011). The determinants may be classified as macro-factors, emanating at national government level, where services of priority are determined, policy and services guidelines are formulated, and considered in the health budget (Naledi et al. 2011).

The next group of determinants are located at the provincial level, and they focus on policy adoption or translation and budgetary allocations, in addition to the identification of resources to build capacity in programme delivery.

Overall, Naledi et al. (2011) advocate development of an oral health policy and unequivocal service guidelines to be incorporated in the health policy document. This incorporation would enhance prioritisation of oral health and consideration in the health budget. Consideration and inclusion of oral health in the health budget could have a positive impact on oral health resources, strategic planning, implementation and evaluation of services. The purpose of this framework is to highlight the need for appropriate skills mix in oral health human resources to deliver optimal oral healthcare, improve access for oral health and ensure sustainability of service provision.

On a practical level, the components highlighted in the conceptual framework could assist oral health planners in identifying the key strategic areas that could determine the successful implementation of national oral health policy. Human resource allocation, such as staffing and skills mix, together with budgetary infrastructure for facility and community-based oral healthcare needs to be clearly identified and supported at all levels of provincial health planning. It is equally important that oral health service delivery is monitored and evaluated using the identified key elements such as appropriateness of services provided, accessibility of oral healthcare and effectiveness of oral health services rendered. This requires close monitoring of the actual services provided so that challenges in service delivery can be easily identified and rectified.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study provided a clear understanding of the challenges facing oral health planners in the province. The proposed framework could be used to identify key areas for oral health policy development and implementation. One limitation of this study is that the framework still needs to be tested to determine its practicality. More research is needed in this area. Another limitation could be the generalisability of the study findings. Despite this limitation, the framework could be a useful tool in health planning in general.

Conclusion

The results of the study indicate that oral health planning in Limpopo province needs more support from a policy and budgetary perspective. Resolving the challenges associated with policy development and budget allocations could contribute to improved oral health service delivery.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following people for their valuable contributions in the preparation of this article:

-

Dr Jeffrey Ramalevhana, PhD, in the statistics section, Department of Health in Limpopo Province, for guidance on data collection and presentation.

-

Mr Abidile Lebotsamang, Research Department of Botswana, for analysing the data collected from oral health professionals by self-administered questionnaires in Limpopo province.

-

Provincial Manager of Oral Health Services and Personal Assistant for proficiently offering statistical data on oral health services and professionals in Limpopo province when requested.

-

Prof. Moses Chimbari, the College Dean of Research, College of Health Sciences at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, for the training in preparation of the proposal for PhD thesis and manuscript writing, critical reading and guidance in preparation of this article.

-

Prof. Benn Sartorius, PhD, Academic Leader for Research (Acting) School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Howard College Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, for the valuable guidance in the presentation of results, critical reading and guidance in preparation of this article.

-

All the participants, oral health professionals of Limpopo province, who took part and made this study possible by providing data with remarkable enthusiasm and honesty trusting that this study would make their voices heard and their input incorporated.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

American Association for Community Dental Programs (AACDP), 2006, A guide for developing and enhancing community oral health programs, viewed n.d., from http://www.aacdp.com. [ Links ]

American Association for Community Dental Programs (AACDP), 2010, A guide for developing and enhancing community oral health programs. [ Links ]

Bailey, K., 1982, Methods of social research, 2nd edn., pp. 83-107, The Free Press, Collier Macmillan Publishers, New York. [ Links ]

Bhayat, A. & Cleaton-Jones, P., 2003, 'Dental clinic attendance in Soweto, South Africa, before and after the introduction of free primary dental health services', Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 31(2), 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00006.x [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V., 2006, 'Using thematic analysis in psychology', in D. Giles, B. Gough & A. Lyons (eds.), Qualitative research in psychology, pp. 77-101, University of Auckland and University of West England, Auckland and Bristol. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Department of Health and Social Development, 2015, Annual Performance Plan 2013/14, Strategic Planning Committee, Polokwane, Limpopo Province. [ Links ]

Magnussen, L., Ehiri, J. & Jolly, P., 2004, 'Comprehensive versus selective primary health care: Lessons for global health policy', Health Affairs 23(3), 167-176. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.167 [ Links ]

Mejia, G., Kaufman, J., Corbie-Smith, G., Rozier, R., Caplan, D. & Suchindran, C., 2008, 'A conceptual framework for Hispanic oral health care', American Association of Public Health Dentistry 68(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00073.x [ Links ]

Naledi, T., Baroni, P. & Schneider, H., 2011, Primary health care since 1994 and implications of the new vision for PHC re-engineering, Health Systems Trust (HST), viewed n.d., from http://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC119087. [ Links ]

Ngulube, P., Mathipa, E.R. & Gumbo, M.T., 2015, 'Theoretical and conceptual framework in the social sciences', in E.R. Mathipa & M.T. Gumbo (eds.), Addressing research challenges: Making headway in developing researchers, pp. 43-66, Mosala-MASEDI Publishers & Booksellers cc, Noordywk. [ Links ]

Oral Health Coordinating Committee (OHCC), 2014, Oral health strategic framework 2014-2017, The United States Public Health Service (USPHS), The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Petersen, P.E., 2008, 'World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health-World Health Assembly 2007', International Dental Journal 58(3), 115-121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1875-595X.2008.tb00185.x [ Links ]

Santa Fe Group, 2003, Expanding access to primary care: New oral health workforce models, The Santa Fe Group, New York University's College of Dentistry, New York City, NY. [ Links ]

Sheiham, A., 2005, 'Oral health, general health and quality of life', Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83(9), 644. https://doi.org/S0042-96862005000900004 [ Links ]

Singh, S., Myburgh, N.G. & Lalloo, R., 2010, 'Policy analysis of oral health promotion in South Africa', Global Health Promotion 17(1), 16-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975909356631 [ Links ]

Thema, L.K. & Singh, S., 2013, 'Integrated primary oral health services in South Africa: The role of the PHC nurse in providing oral examination and education', African Journal for Primary Health Care, Family Medicine 5(1), a413. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.413 [ Links ]

Thema, L.K. & Singh, S., 2017, 'Oral health service delivery in Limpopo Province', South African Dental Journal 72(7), 310-314. https://doi.org/10.17159/2519-0105/2017/v72no7a3 [ Links ]

United States Public Health Service, 2014, U S Department of Health and Human Services Oral Health Strategic Framework 2014-2017, The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDoHHS), Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, P.J. & Van Wyk, C., 2004, 'Oral health in South Africa', International Dental Journal 54(S6), 373-377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1875-595X.2004.tb00014.x [ Links ]

Zuber-Skerritt, O., 2015, 'Participatory action learning and action research (PALAR) for community engagement: A theoretical framework', Educational Research for Social Change (ERSC) 4(1), 5-25. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lawrence Thema

klthema1@gmail.com

Received: 02 Feb. 2018

Accepted: 13 Mar. 2019

Published: 23 Sept. 2019