Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.21 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.09.004

FULL LENGTH ARTICLE

Basic student nurse perceptions about clinical instructor caring

Gerda-Marie Meyer; Elsabe Nel*; Charlene Downing

University of Johannesburg, P.O Box 523, Auckland Park, 2006 South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Caring is the core of nursing and should be cultivated in student nurses. However, there are serious concerns about the caring concern in the clinical environment and in nursing education. Clinical instructors are ideally positioned to care for student nurses so that they in turn, can learn to care for their patients.

METHODS: A descriptive, comparative, cross-sectional and correlational quantitative research design with convenience sampling was conducted to describe the perceptions of junior student nurses (n = 148) and senior student nurses (n = 168) regarding clinical instructor caring. A structured self administered questionnaire using the Nursing Student Perceptions of Instructor Caring (NSPIC) (Wade & Kasper, 2006) was used. Descriptive statistics and hypotheses testing using parametric and non parametric methods were conducted. The reliability of the NSPIC was determined.

RESULTS: Respondents had a positive perception of their clinical instructors' caring. No relationship could be found between the course the respondents were registered for, the frequency of contact with a clinical instructor, the ages of the respondents and their perceptions of clinical instructor caring. The NSPIC was found to be reliable if one item each from two of the subscales were omitted.

CONCLUSIONS: Student nurses perceived most strongly that a caring clinical instructor made them feel confident, specifically when he/she showed genuine interest in the patients and their care, and when he/she made them feel that they could be successful.

Keywords: Perceptions; Caring; Clinical instructors; Student nurses; Quantitative research

1. Background

The purpose of this article is to describe the findings of a study on the perceptions of student nurses enrolled at a private nursing education institution in South Africa about clinical instructor caring. The carative factors, as described by Watson (1979, p. 9), were used as the theoretical framework for the study. Caring is a core value in nursing practice, and therefore a desired attribute in student nurses (Mlinar, 2010, p. 491). Caring for students during their nursing education is important, as this is where student nurses are able to learn about the essence of their profession (Begum & Slavin, 2012, p. 332). It enables them to form their own values as they progress in their nursing programme and later enter the profession (McEnroe-Petitte, 2014, p. 6). Clinical instructors are in an ideal position to care for student nurses and should be chosen carefully, to demonstrate the values of care and caring (Fassetta, 2011, p. 89). Their influence is likely to be particularly powerful in the development of the moral nature of nursing practice (King, Jackson, Gallagher, Wainwright, & Lindsay, 2009, p. 142).

Student nurses describe caring clinical instructors as those who express interest in their wellbeing and learning, provide personalised attention and guidance, and who are flexible in response to unexpected events. They respectfully share information with student nurses and develop an appreciation of life's meaning in them. Caring clinical instructors are also encouraging, listen to student nurses and provide them with tangible support. Such clinical instructors are kind and respectful to student nurses but are also able to set limits (Begum & Slavin, 2012, pp. 334-335; Hall, 2010, p. 57; Nelson, 2011, p. 180; Roe, 2009, p. 211 & 237). Student nurses require being positively regarded and want to be allowed to live their personalities and compassion. They want clinical instructors to honour their learning processes and would like to be creative. When a clinical instructor has passion for her/his subject, it is contagious, and student nurses find it easy to learn (Elcigil & Sari, 2008, p. 121; Hill, 2014, p. 63; Sandvik, Eriksson, & Hilli, 2014, pp. 289-290). Student nurses have a strong desire to need to know their own progress. They need to receive immediate feedback on their position in relation to their knowledge and skills, to ascertain where they stand, and whether or not they live up to the work-life expectations. A lack of feedback is considered to be a mental strain for student nurses (Maxwell, Black, & Baillie, 2015, p. 40; Tiwaken, Caranto, & David, 2015, p. 70).

Student nurses experience high levels of stress, due to rigorous academic and emotional demands when they begin to take responsibility for patient care. That stress decreases student nurses' ability to think critically and impacts on their experiences while involved in a nursing programme. It may also later impact on their lives and journeys as registered nurses (Roe, 2009, p. 211). Stress is perceived as a challenge when student nurses have a relationship of care with their clinical instructors, when clinical instructors model effective communication, when they inform the registered nurses about student nurse skills levels, and, when they set realistic goals for clinical experiences. Student nurses are then less anxious and more satisfied with their programmes (Begum & Slavin, 2012, p. 334; Hall, 2010, p. 57; Nelson, 2011, p. 180; Reeve, Shumaker, Yearwood, Crowell, & Riley, 2013, p. 423; Roe, 2009, p. 237). Poor relationships between student nurses and clinical instructors are a source of stress and could result in them losing interest in learning. Creating and establishing a clinical instructor-initiated caring transaction, linked to taught self-care interventions, has the potential to reduce their anxiety while enhancing learning outcomes and critical thinking. The caring transaction is a vehicle for clinical instructors to assist student nurses to find meaning in the anxiety, and guide them to engage in self-care, using the practice of mindfulness and reflection. Student nurses have multiple emotional needs. These are varied and personal in nature. It is essential that clinical instructors ensure that time is provided to focus on emotional needs (Hutchinson & Goodin, 2013, pp. 22-23; Tiwaken et al., 2015, p. 70).

Student nurses who perceive their instructors as caring also perceive themselves to be caring (Labrague, McEnroe-Petitte, Papathanasiou, Edet, & Arulappan, 2015, p. 344), and report increased self-confidence (Nelson, 2011, p. 172; Roe, 2009, p. 259). Caring clinical instructor interaction with student nurses in the clinical environment causes them to perceive this environment as stimulating, and a challenge. Being cared for strengthens their ability to cope with sources of stress. Student nurses who feel cared for and valued are empowered to be confident in their clinical practice (Roe, 2009, p. 254). Striving towards supporting student nurses in their learning, ensuring that they feel included, and treating them with respect should be fundamental to any clinical environment. Failure of nursing as a profession to acknowledge the importance of student nurse empowerment carries risks. There is a chance that it will produce nurses who are ill-equipped to fully support those in their care (Begum & Slavin, 2012, p. 335; Bradbury-Jones, Sambrook, & Irvine, 2011, p. 371).

Exposure to the process of nursing education seems to reduce the capacity for expressive care in student nurses (Murphy, Jones, Edwards, James, & Mayer, 2009, p. 263). The high enthusiasm and belief in the ability to care may result in higher perceptions of caring in junior student nurses. By the time they reach their final year, their initial beliefs about entering the nurse-patient relationship may be tempered with realism about the complexities of this relationship. The stress of nursing school, the foreign and fast-paced clinical environment, or other distractions affect the ability of student nurses to form deeper perceptions of the patient context that should ultimately result in high empathy levels (Lovan & Wilson, 2012, p. 30). Uncaring practice leaves student nurses feeling vulnerable, uncertain and at risk of abandoning their compassionate practice ideals and behaviours. When the culture in clinical practice is incompatible with student nurses' ethical ideals, they may lack the courage to openly stand up for their values, coping by caring when alone with the patients, or by compromising their ethical ideals. Their moral sensitivity or inner voice is at risk of being suppressed, leading to inhibited ethical formation, thereby hindering ethical decision making according to the core values of nursing (Curtis, 2014, p. 219; Pedersen & Sivonen, 2012, p. 846).

Knowledge about student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring can assist clinical instructors to improve their performance by developing appropriate caring behaviours (Madhavanprabhakaran, Shukri, Hayudini, & Narayanan, 2013, p. 43). It can also be used for decision making and development of clinical nursing instructor training, to measure quality in nursing education, and to inform nursing education curriculi and programme content (Letzkus, 2005, p. 4).

2. Problem statement

An ethic of caring in South African nursing is entrenched in the Nursing Act (33 of 2005), the code of ethics for nursing practitioners in South Africa, the Ubuntu philosophy, and the European influence of the nineteenth century that shaped South African nursing. However, current South African research indicates a lack of caring manifested in insensitivity towards patients' emotional needs (Van den Heever, Poggenpoel, & Myburgh, 2013, p. 1), dysfunctional nursing leadership (Blignaut, Siedine, Coetzee, & Klopper, 2014, p. 229), and negative press reporting (Oosthuizen, 2012, p. 60). Poor practice environments for nurses are reported (Coetzee, Klopper, Ellis, & Aiken, 2013, p. 170), mainly caused by staff shortages, poor staff retention and violence against nurses (Bimenyimana, Poggenpoel, Myburgh, & van Niekerk, 2009, p. 4; George, Quinlan, Reardon, & Aguilera, 2012, p. 6; Jacobs, 2013, p. 78; Kennedy & Julie, 2013, p. 1). Nursing education is affected by these problems, and a degree of uncaring clinical nursing education is evident in the literature. According to Watkins, Roos, and Van der Walt (2011, pp. 8-9), registered nurses appear to have a negative attitude that student nurses interpret as a lack of consideration towards patients. Student nurses may conclude that nurses no longer have a passion for nursing because of their failure to do their work thoroughly. These researchers expressed concern about a collective environment that is not conducive to the wholistic wellbeing of student nurses as well as patients, and that nurses in charge of supervision during clinical training often make student nurses feel uncomfortable and unwelcome. Student nurses are regarded as part of the workforce which delays completion of objectives, and which, according to Bradbury-Jones et al. (2011, p. 368) can cause students to feel devalued as learners. There is insufficient clinical learning as well as a lack of clinical and emotional support (Mogale, 2011, p. 88). They experience horizontal violence by peers, lack of supervision of their learning, lack of learning opportunities, and a deficient sense of belonging (Caka & Lekalakala-Mokgele, 2013, p. 9).

3. Research purpose

The purpose of the study was to investigate the perceptions of student nurses regarding clinical instructor caring at a private nursing education institution in South Africa, and to provide recommendations for caring clinical instruction.

4. Research objectives

a) To identify and describe the perceptions of student nurses at a private nursing education institution in South Africa of clinical instructor caring.

b) To determine and examine the relationships between student nurse perceptions of clinical instructor caring and years of formal nursing education successfully completed, frequency of contact with a clinical instructor, and age.

c) To provide recommendations for clinical instructor practice, educational policy and further research about caring for student nurses.

5. Research method

A descriptive, comparative, cross-sectional and correlational quantitative research design was used.

6. Population and sampling

The target population in this study represented student nurses registered at the private nursing education institution:

a) For the first year of the two-year course leading to enrollment as a nurse in terms of Regulation 2175 of the South African Nursing Council (SANC). The inclusion criterion for this group was students who had experienced a minimum of six months of clinical nursing placement. For the purposes of the study this group of student nurses was referred to as junior student nurses.

b) For the second year of the two-year bridging course for enrolled nurses leading to registration as a general nurse in terms of Regulation 683 of the SANC. No inclusion criteria were determined for this group. For the purposes of the study this group of student nurses was referred to as senior student nurses.

The accessible population was student nurses in the target population who were registered at the largest of five campuses of the private nursing education institution in South Africa. The campus is situated in the Gauteng province. The accessible population size was N = 347, N = 148 for the junior student nurses and N = 199 for the senior student nurses. The acceptance rate for the junior student nurses was n = 122 (82%) and n = 168 (85%) for the senior student nurses. Convenience sampling was used.

7. Data collection and instrument

A structured self-administered questionnaire was used. The researchers administered the questionnaire to the respondents in person in October 2013. A box with a slot was provided for the respondents to drop their questionnaires into. The questionnaires were coded for statistical purposes. Section one of the questionnaire determined the perceptions of the respondents about clinical instructor caring. This section, with its 31 closed-item statements, using a 6 point Likert scale, was the Nursing Students' Perceptions of Instructor Caring (NSPIC), developed by Wade and Kasper (2006, p. 166), to determine student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring. Of the 31 statements, 19 were expressed in positive terms and 12 in negative terms. The authors categorised the 31 items into five subscales namely Instills confidence through caring, Supportive learning climate, Appreciation of life's meaning, Control vs. flexibility and Respectful sharing. The reliability of the NSPIC subscales was determined by the designers of the instrument and subsequently by three other authors. The highest Cronbach's alpha (0.96) was reported for the subscale "Instills confidence through caring" by the authors (Wade & Kasper, 2006, p. 167) and the lowest Cronbach's alpha (0.40) was reported for the subscale "Respectful sharing" by Nelson (2011, p. 106). The wording of three of the items was changed by the researchers, in order to be suitable to the South African context and the context of the nursing education institution under study. Consent was received from the designers of the NSPIC to affect these changes.

Section two of the questionnaire provided information about the course the respondent was registered for, the gender, ethnicity and age of the respondents, as well as the frequency of clinical instructor contact. A pretest was conducted with ten junior student nurses who met the inclusion criterion and ten senior student nurses. As a result of the findings of the pretest, minor adaptations were made to section two of the questionnaire.

8. Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the University of Johannesburg (AEC21-01-2013) and the health care institution to which the private nursing education institution was affiliated (UNIV-2013-0018). Respondents were informed verbally and in writing by means of an information letter about the purpose of the research, as well as the data collection method. They were assured about their rights to self-determination, privacy, anonymity, confidentiality, fair treatment and protection from discomfort and harm (Grove, Burns, & Gray, 2013, pp. 163-182). The researchers offered to answer any pertinent questions with respect to the research. Information was provided in English, with which the respondents were familiar. Comprehension of the consent information was tested orally by the researchers. Written consent was obtained from all respondents.

9. Validity and reliability

9.1. Internal validity

In order to minimise threats to the internal validity of this study, student nurses who took part in the pretest conducted in this study were excluded during data collection, to eliminate the testing effect. Although random selection was not used in the study, a response rate of 84% of the accessible population was achieved which minimised a potential selection threat (Grove et al., 2013, p. 200).

9.2. External validity

Maximising participation in the study was enhanced by collecting the data on days when the respondents were attending lectures on campus. Sufficient data was collected from the respondents with regard to age, gender and ethnicity to allow the researchers to become familiar with these characteristics, and to compare them to similar characteristics in the target population. The use of only one inclusion criterion for the junior student nurses and no inclusion criteria for the senior student nurses, further aided to enhance the ability to generalise the findings of the study. The setting in which the data was collected was similar to that of the target population, and the clinical teaching and learning model was identical at all campuses. This enhanced the generalisability of the findings of the study.

9.3. Reliability

Cronbach's alpha coefficient and the mean inter-item correlation were conducted to estimate the internal consistency of each subscale of the NSPIC. All factors with a reliability coefficient above 0.7 were considered as acceptable for this study (Grove et al., 2013, p. 392). All mean inter-item correlations above 0.2 were considered as acceptable (Pallant, 2010, p. 95). Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the total NSPIC was 0.94, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the first three subscales was well above the required 0.7. The mean inter-item correlations for the first three subscales were also above the required 0.2. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for subscale four was low (0.61). The mean inter-item correlation was at the required level (0.29). When item 30 "Is inflexible when faced with unexpected situations (happenings)" was omitted from this subscale, Cronbach's alpha coefficient increased slightly to 0.62, and the mean inter-item correlation increased to 0.37. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for subscale five was low (0.27), and so was the mean inter-item correlation (0.16). When item 12 "Does not reveal any of his or her personal side" was omitted, Cronbach's alpha coefficient increased to 0.83, and the mean inter-item correlation increased to 0.70. Based on the findings of the reliability testing, it was concluded that the subscales of the NSPIC (excluding items 12 and 30) were internally consistent. The NSPIC was found to be a reliable measure of student nurse perceptions of clinical instructor caring, if excluding items 12 and 30 from the instrument.

10. Data analysis

A total of 290 questionnaires were analysed, 122 for the junior student nurses and 168 for the senior student nurses. Both sections of the questionnaire were analysed, using IBM SPSS version 22.0. Descriptive statistics were computed for the biographical data of the respondents, the course for which they were registered, the frequency of clinical instructor contact, and their perceptions of clinical instructor caring. Both parametric and non-parametric inferential statistics were computed to test the distribution of the data and the hypotheses because of the abnormal distribution in the presence of a large sample size (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 411). A p - value of ≤0.05 was considered as a significant difference on the 5% level of significance. The effect size was interpreted according to Cohen's criteria: 0.1 = small effect, 0.3 = medium effect, 0.5 = large effect (Cohen, in Pallant, 2010, p. 223).

11. Research findings

11.1. Descriptive statistics

The acceptance rate for the total sample was n = 290 (84%). The junior student nurses accounted for 42% (n = 122), and senior student nurses accounted for 58% (n = 168) of the sample.

11.1.1. Biographical data

Ninety two percent (92%) of respondents were female (n = 268) and reflected the gender distribution of the target population, where 92% of the student nurses were female, and 8% were male. Eighty nine percent (89%) of the respondents were African (n = 257). Compared to the target population, Africans were over-represented in both the junior and senior student nurse samples. The ethnicity of student nurses at all five campuses of the private nursing education institution under study was dominated by black student nurses. However, at campuses in some of the provinces there was greater representation of coloured and white student nurses, according to the South African demography. The mean age of the junior student nurses was 26.8 years, and the mean age of the senior student nurses was 31.29 years. The range for age for the junior student nurses was 25 years and the range for age for the senior student nurses was 31 years.

11.1.2. Frequency of clinical instructor contact

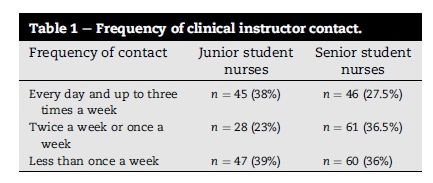

The frequency of clinical instructor contact was collapsed and is illustrated in Table 1. Junior student nurses reported higher contact frequencies with a clinical instructor than senior student nurses. More than a third of all respondents (39% for the junior student nurses and 36% of the senior student nurses) did not have contact with a clinical instructor every week.

11.1.3. Perceptions of clinical instructor caring

Both the junior and senior student nurses showed the highest level of agreement for item one "Shows genuine interest in patients and their care", and the lowest level of agreement for negatively worded item six "Makes me feel like a failure." The mean scores for item one were higher for the junior student nurses (M = 5.31, SD = 0.977) than for the senior student nurses (M = 5.07, SD = 0.958). The mean scores for item six were higher for the senior student nurses M = 5.07, SD = 0.958) than for the junior student nurses (M = 1.90, SD = 1.257).

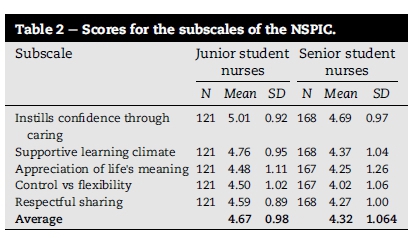

Table 2 illustrates the scores for the subscales of the NSPIC. The average mean score for the junior student nurses was higher (4.667) than that of the senior student nurses (4.322). The mean scores for the junior student nurses were higher than the mean scores for the senior student nurses in all the subscales. The mean scores for both junior and senior student nurses were the highest for subscale 1 "Instills confidence through caring." The lowest mean score for the junior student nurses were for subscale 3 "Appreciation of life's meaning". The lowest mean score for the senior student nurses were for subscale 4 "Control vs flexibility".

Further analysis of the data is described without item 30 for the subscale "Control vs flexibility", and without item 12 for the subscale "Respectful sharing" as a result of the analysis of the internal consistency of the subscales, as described in paragraph nine.

11.2. Testing of the hypotheses

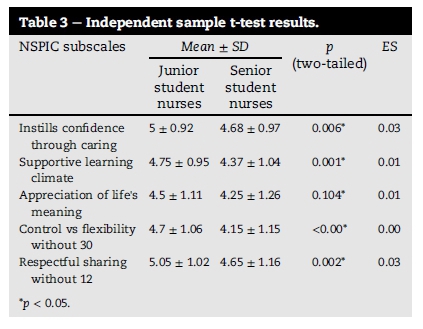

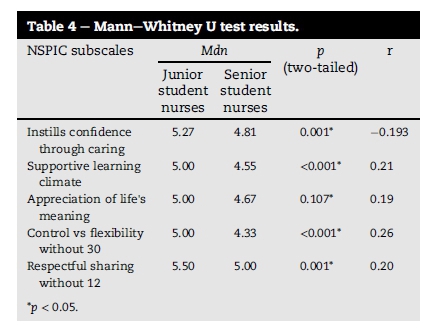

Hypothesis one was tested, using an independent sample t-test and a Mann-Whitney U test (Table 3 and Table 4).

Ho1. There is no relationship between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the years of formal nursing education he/she has completed successfully.

Ha1. The more years of formal nursing education a student nurse has completed successfully, the more positively clinical instructor caring is perceived.

The null hypothesis could not be rejected because of the small effect sizes in all the significant subscales, and because of the non-significant difference in perceptions between the junior and senior student nurses in subscale three. There was no statistical relationship between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the years of formal nursing education completed successfully.

Hypothesis two was tested, using a one-way ANOVA test (Table 5) and a Kruskal-Wallis test (Table 6).

Ho2. There is no relationship between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the frequency of contact with the clinical instructor.

Ha2. The more frequently a student nurse has clinical instructor contact, the more positively clinical instructor caring is perceived.

Frequency of contact was divided into six groups (everyday, four times a week, three times a week, twice a week, once a week, and less than once a week). There was no statistically significant difference among the six groups with respect to any of the subscales, except subscale three "Appreciation of life's meaning", where the effect size was small. Despite achieving statistical significance, the actual differences among the mean scores between the groups were quite small. Post hoc comparisons, using the Hochberg test, were conducted to isolate the differences between group means (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 417), and to protect against the likelihood of a Type 1 error (Pallant, 2010, p. 242). The test results indicated that there were no statistically significant differences among the groups for all the subscales, at the p ≤ 0.05 level in all cases. This was confirmed by the homogeneous subsets at the p ≤ 0.05 level in all groups, in all subsets. The result of the Brown-Forsythe test was 0.04. The null hypothesis could not be rejected.

Hypothesis three was tested, using a Pearson's correlation and a Spearman's Rho test.

Ho3. There is no relationship between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the age of the student nurse.

Ha3. The older a student nurse is, the more positively clinical instructor caring is perceived.

The results are shown in Table 7.

There were no significant correlation between the ages of the respondents and their perceptions of clinical instructor caring, except in subscale four, "Control vs. flexibility", where there was a negative correlation between age and student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring. The null hypothesis could not be rejected.

12. Discussion

The findings demonstrated that both junior and senior student nurses perceived their clinical instructors as more caring than uncaring. Both junior and senior student nurses also perceived their clinical instructor to most frequently instil confidence in them because they were caring. The junior student nurses perceived their clinical instructors to least frequently care for them by assisting them to appreciate life's' meaning. The senior student nurses perceived their clinical instructors to least frequently care for them by being flexible. Although the mean scores for the subscales of the NSPIC were higher for junior student nurses than for senior student nurses, no statistically significant relationship could be found between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the years of formal nursing education he/she had completed successfully. There was no relationship between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the frequency of contact with the clinical instructor, although it appears that clinical instructor contact three or four times a week resulted in higher scores for perceptions of clinical instructor caring. There was also no relationship between a student nurse's perceptions of clinical instructor caring and the age of the student nurse, except in subscale four, without item 30, where there was a negative correlation between age and student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring.

13. Lessons learned

This study does not provide any data about how clinical instructor caring is perceived by second-year pupil enrolled nurses and first-year bridging course student nurses at the nursing education institution under study. A quantitative research design was used to describe perceptions of student nurses which provided valuable information in the South African private nursing education context. However, richer descriptions and an enhanced understanding of not only how student nurses perceive clinical instructor caring, but also why, is required. Because of the differences in representation of coloured, Indian and white students at the various campuses of the nursing education institution, stratified random sampling should be used in further research, should ethnicity be critical for achieving representativeness.

14. Recommendations

14.1. Clinical instructor practice

Specific attention should be paid to assist junior student nurses to appreciate life's meaning, by assisting them to reflect on the personal meaning of their experiences, encouraging them to value others' perspectives about life, and assisting them to understand the spiritual dimensions of their lives. Clinical instructors should demonstrate flexibility when they accompany senior and older student nurses by not making demands on their time, thereby interfering with their personal needs, and by being focused on patient needs rather than on completion of tasks. Clinical instructors should be flexible when the unexpected occurs in senior and older students' lives. Although a statically significant relationship could not be found between student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring and frequency of clinical instructor contact, clinical instructors should be aware that sufficient literature sources indicate that frequent clinical instructor contact is viewed as caring clinical instructor behaviour and results in better clinical competency. Clinical instructors should plan to have frequent contact with their student nurses in the clinical setting. The frequency and duration of such contact sessions should be tailored to the student nurse's needs.

14.2. Educational policy

The job descriptions and workload strategies of clinical instructors should be tailored to the needs of student nurses for frequent clinical instructor contact of sufficient duration. The NSPIC should be used as a measure to evaluate caring nursing education and clinical instructor excellence.

14.3. Research

Further research should be conducted at the nursing education institution and other settings, in order to study student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring in all years of nursing study, with large samples, using probability sampling methods. A pragmatic research approach to student nurses' perceptions of clinical instructor caring should be used in future research, to enhance the knowledge of this important construct. The relationship between student nurse perceptions of clinical instructor caring, and the duration of clinical instructor contact at the nursing education institution should be researched. Subscale four and subscale five of the NSPIC should be revised, to improve the internal consistency of these subscales.

15. Conclusions

How caring demonstrated by clinical instructors is perceived by student nurses may be an indicator of how caring student nurses will be once they enter the profession. Caring is love. It manifests and perpetuates itself both subtly and explicitly. It comes from the heart, and is complex in its simplicity. This necessitates that it should be studied, understood, voiced and consciously practised. Nurses, regardless of where they practice and who they deal with, cannot afford to keep their distance from the obligation to care, if they wish to add value and meaning and not harm those who come across their way. The use of a caring theory in nursing practice and a caring curriculum in nursing education institutions should be considered with a sense of urgency for the survival of nursing in this ever-changing post-modern health care world, where caring tends to be trivialised at the expense of the hearts of patients, families, communities and nurses alike. Conducting this research created awareness and began the conversation regarding caring nursing education in the nursing education institution under study. Great enthusiasm for caring for patients, students and colleagues alike, role modelling, teaching and research are frequent conversation themes nowadays, and has made it to meeting agendas, even those of nurse executives. This study, like scores of others, has blessed nursing and nursing education with multiple new research questions which current and future nurse carers will endeavour to respond to.

References

Begum, S., & Slavin, H. (2012). Perceptions of "caring" in nursing education by Pakistani nursing students: An exploratory study. Nurse Education Today, 32(3), 332e336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.10.011. [ Links ]

Bimenyimana, E., Poggenpoel, M., Myburgh, C., & van Niekerk, V. (2009). The lived experience by psychiatric nurses of aggression and violence from patients in a Gauteng psychiatric institution. Curationis, 32(3), 4e13. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v32i3.1218. [ Links ]

Blignaut, A. J., Siedine, K., Coetzee, S. K., & Klopper, H. C. (2014). Nurse qualifications and perceptions of patient safety and quality of care in South Africa. Nursing and Health Sciences, 16(2), 224e231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12091. [ Links ]

Bradbury-Jones, C., Sambrook, S., & Irvine, F. (2011). Empowerment and being valued: A phenomenological study of nursing students' experiences of clinical practice. Nurse Education Today, 31(4), 368e372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.07.008. [ Links ]

Caka, E. M., & Lekalakala-Mokgele, S. (2013). The South African military nursing college pupil enrolled nurses' experiences of the clinical learning environment. Health SA Gesondheid, 18(1), 1e11. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.611. [ Links ]

Coetzee, S. K., Klopper, H. C., Ellis, S. M., & Aiken, L. H. (2013). A tale of two systemsdnurses practice environment, well being, perceived quality of care and patient safety in private and public hospitals in South Africa: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(2), 162e173. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-www.sciencedirect.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Curtis, K. (2014). Learning the requirements for compassionate practice: Student vulnerability and courage. Nursing Ethics, 21(2), 210e223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0969733013478307. [ Links ]

Elcigil, A., & Sari, H. (2008). Students' opinions about and expectations of effective nursing clinical mentors. Journal of Nursing Education, 47(3), 118e123. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Fassetta, M. E. (2011). Faculty utilization of role modeling to teach caring behaviors to baccalaureate nursing students (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database: (UMI No 3492907). [ Links ]

George, G., Quinlan, T., Reardon, C., & Aguilera, J. (2012). Where are we short and who are we short of? A review of the human resources for health in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 17(1), 1e7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v17i1.622. [ Links ]

Grove, S. K., Burns, N., & Gray, J. R. (2013). The practice of nursing research. Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence (7th ed.). St. Louis Missouri: Saunders. [ Links ]

Hall, L. R. (2010). Perceptions of faculty caring: Comparison of distance and traditional graduate nursing students (Doctoral thesis). Available fromProQuestDissertations&Thesesdatabase:(UMINo3404439). [ Links ]

Hill, L. H. (2014). Graduate students' perspectives on effective teaching. Adult Learning, 25(2), 57e65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1045159514522433. [ Links ]

Hutchinson, T. L., & Goodin, H. J. (2013). Nursing student anxiety as a context for teaching/learning. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 31(1), 19e24. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Jacobs, W. O. (2013). Strategies to promote the health of student nurses at a higher education institution (HEI) in Johannesburg who has experienced aggression (Doctoral thesis). Auckland Park, Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. Available from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Kennedy, M., & Julie, H. (2013). Nurses' experiences and understanding of workplace violence in a trauma and emergency department in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 18(1), 1e9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.663. [ Links ]

King, L. K., Jackson, M. T., Gallagher, A., Wainwright, P., & Lindsay, J. (2009). Towards a model of the expert practice educator e Interpreting multi-professional perspectives in the literature. Learning in Health and Social Care, 8(2), 135e144. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Labrague, L., McEnroe-Petitte, D., Papathanasiou, I., Edet, O., & Arulappan, J. (2015). Impact of instructors' caring on students' perceptions of their own caring behaviors. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(4), 338e346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12139. [ Links ]

Letzkus, M. W. (2005). Nursing student perceptions of a clinical instructor (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database: (UMI No 3209897). [ Links ]

Lovan, S. R., & Wilson, M. (2012). Comparing empathy levels in students at the beginning and end of a nursing program. International Journal for Human Caring, 16(3), 28e33. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Madhavanprabhakaran, G. K., Shukri, R. K., Hayudini, J., & Narayanan, S. K. (2013). Undergraduate nursing students' perception of effective clinical instructor: Oman. International Journal of Nursing Science, 3(2), 38e44. http://dx.doi.org/10.5923/j.nursing.20130302.02. [ Links ]

Maxwell, E., Black, S., & Baillie, L. K. (2015). The role of the practice educator in supporting nursing and midwifery students' clinical practice learning: An appreciative inquiry. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 5(1), 35e45. http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v5n1p35. [ Links ]

McEnroe-Petitte, D. M. (2014). Caring in traditional and nontraditional nursing students (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database: (UMI No 3625901). [ Links ]

Mlinar, S. (2010). First- and third-year student nurses' perceptions of caring behaviours. Nursing Ethics, 17(4), 491e500. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Mogale, L. C. (2011). Student nurses' experiences of their clinical accompaniment (Master's dissertation). Pretoria: University of South Africa. Available from: http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/6297/dissertation_mogale_l.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [ Links ]

Murphy, F., Jones, S., Edwards, M., James, J., & Mayer, A. (2009). The impact of nurse education on the caring behaviours of nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 29(2), 254e264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2008.08.016. [ Links ]

Nelson, N. (2011). Beginning nursing students' perceptions of the effective characteristics and caring behaviours of their clinical instructor (Doctoral thesis). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database: (UMI No 3449130). [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, M. J. (2012). The portrayal of nursing in South African newspapers: A qualitative content analysis. Africa Journal of Nursing & Midwifery, 14(1), 49e62. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-reference.sabinet.co.za.ujlink.uj.ac. [ Links ]

Pallant, J. (2010). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS (version 22) (4th ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Pedersen, B., & Sivonen, K. (2012). The impact of clinical encounters on student nurses' ethical caring. Nursing Ethics, 19(6), 838e848. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing Research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. [ Links ]

Reeve, K. L., Shumaker, C. J., Yearwood, E. L., Crowell, N. A., & Riley, J. B. (2013). Perceived stress and social support in undergraduate nursing students' educational experiences. Nurse Education Today, 33(4), 419e424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.009. [ Links ]

Roe, D. C. (2009). The relationship between pre-licensure baccalaureate nursing students' stress and their perceptions of clinical nurse educator caring (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database: (UMI No 3351570). [ Links ]

Sandvik, H., Eriksson, K., & Hilli, Y. (2014). Becoming a caring nurse e A nordic study on students' learning and development in clinical education. Nurse Education in Practice, 14(3), 286e292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.11.001. [ Links ]

Tiwaken, S. U., Caranto, L. C., & David, J. J. T. (2015). The real World: Lived experiences of student nurses during clinical practice. International Journal of Nursing Science, 5(2), 66e75. http://dx.doi.org/10.5923/j.nursing.20150502.05. [ Links ]

Van den Heever, A. E., Poggenpoel, M., & Myburgh, C. P. H. (2013). Nurses and care workers' perceptions of their nurse-patient therapeutic relationship in private general hospitals, Gauteng, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 18(1), 1e7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.727. [ Links ]

Wade, G., & Kasper, N. (2006). Nursing students' perceptions of instructor caring: An instrument based on Watson's theory of transpersonal caring. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(5), 162e168. Available from CINAHL with Full Text: http://0-web.a.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za. [ Links ]

Watkins, K. D., Roos, V., & Van der Walt, E. (2011). An exploration of personal, relational and collective well-being in nursing students during their training at a tertiary education institution. Health SA Gesondheid, 16(1), 1e10. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v16i1.552. [ Links ]

Watson, J. (1979). The philosophy and science of caring. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [ Links ]

Received 20 April 2016

Accepted 14 September 2016

Available online 27 October 2016

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: Gerda.Meyer@netcare.co.za (G.-M. Meyer), ewnel@uj.ac.za (E. Nel), charlened@uj.ac.za (C. Downing).

Peer review under responsibility of Johannesburg University.