Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.21 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.08.002

FULL LENGTH ARTICLE

Scholarship in nursing: Degree-prepared nurses versus diploma-prepared nurses

Lizeth RoetsI, *; Yvonne BotmaII; Cecilna GroblerIII

IDepartment of Health Studies, University of South Africa, Muckleneuk Ridge Campus, Pretoria 3000, South Africa

IISchool of Nursing, University of the Free State PO Box 339, Bloemfontein 9301, South Africa

IIISchool of Nursing, University of the Free State, PO Box 99, Bloemfontein 9301, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The nursing profession needs nurses with a higher level of education and not merely more nurses to enhance patient outcomes. To improve quality patient care the nursing discipline needs to be advanced through theory development and knowledge generation, thus graduate nurses. Nursing scholarship cannot be limited to nurse academics, but is the responsibility of every nurse.

Although the world is looking towards combating the decline in nursing numbers with better educated nurses, South Africa is planning to address the problem with more lower qualified nurses.

AIM: The aim of this study being reported here was to establish whether degree-prepared nurses in South-Africa partake more often in scholarly activities than diploma-prepared nurses.

METHOD: A cross-sectional descriptive design was used. The population was all professional nurses registered with the South African Nursing Council who obtained either a four year degree or four year diploma in nursing. Data were gathered from 479 respondents, using a self-administrative questionnaire.

RESULTS: Three times more nursing educators (n = 19) achieved a degree as first qualification than their colleagues (n = 6) who achieved a diploma as first qualification. All but one (n = 18) nursing educators who obtained a degree as first qualification are educators in the private sector that include both universities as well as nursing colleges of private hospital groups.

Data further revealed that most nurse educators and those in managerial positions were degree prepared. More degree prepared nurses than diploma prepared nurses were actively involved in scholarly activities such as research (30,5% compared to 25,5%) and implementing best practice guidelines (62,2% compared to 55,9%).

CONCLUSION: The global nursing crisis, nor the nursing profession, will benefit by only training more nurses. The profession and the health care sector need more degree prepared nurses to improve scholarship in nursing.

Keywords: Degree nurses; Diploma nurses; Knowledge generation; Scholarship; Scholarly activities

1. Introduction

The various entry levels into nursing practice have been contentious and the topic of discussion amongst policy makers, researchers and the nursing profession. The necessity of graduate education for nursing and midwifery has therefore also been debated (Swindells & Willmott, 2003) and an all-graduate profession has been considered and recommended (Beach, 2002). Contrary to Beachs' viewpoint, many stakeholders are of the opinion that all cadres of nurses are needed in the profession. Practice leaders and researchers indicate that, although diploma and degree programmes contain the same content, degree programmes provide students with a more in-depth study of the physical and social sciences, nursing research, leadership and management, as well as community and public health nursing (Johnston, 2009).

However, no differentiation between degree-qualified and diploma-qualified nurses occurs in clinical practice currently. The duration of both the degree and diploma programmes is four years. On exiting the programmes all diplomats and graduates, register with the South African Nursing Council as a general, community health- and psychiatric nurse and midwife. Furthermore, there is no salary or rank differentiation between the two groups of registered nurses.

There is an increase in public recognition of nurses' significant role to shape the future of healthcare through evidenced based care, therefore the demand for more degree-prepared nurses become evident (Beach, 2002). Many countries such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and others requires a bachelors degree as entry into professional nursing (Aiken et al., 2014). Doctoral prepared nurses could significantly contribute towards building an evidence-based pool of nursing knowledge, furthering nursing and nurses' scholarship.

2. Literature review

Scholarship in nursing is defined as "not only research (the scholarship of discovery) but also the scholarship of integration (critical thinking), the scholarship of application (knowledge translation), and the scholarship of teaching. The meanings of these four forms of scholarship are "separate yet overlapping" (Boyer and Rice as cited in Glassick, 2000). The scholarship of discovery refers to nursing research that includes interdisciplinary and collaborative research to improve practise and healthcare while the scholarship of integration emphasises the interconnection of ideas that can bring new insight. The transfer of the science and art of nursing from the expert to the novice nurse can be defined as the scholarship of teaching. Scholarship of practice (application) has emerged as a critical component in clinical competence; thus, it encompasses all aspects of nursing care where solving healthcare problems are evident (Glassick, 2000). Nurse clinicians should at the minimum be able to demonstrate critical thinking (scholarship of integration) and implement best available evidence in practice (scholarship of application). Incompetence in these two types of scholarly activities may directly impede quality of care.

Increasing the number of lower cadre may challenge the quality of nursing care. There is strong evidence that the mortality rate of hospitalised patients decrease when the majority of nursing staff are degree qualified (Aiken et al., 2014). Furthermore, degree prepared nurses and nurse researchers are needed to advance evidence based practice as well as the science of nursing. Such evidence-based practice will free the profession from the bondage of "traditional" practices as well as from the unconsidered application of theory into practice (book knowledge).

Although all cadres of nurses are valued and needed in the profession, diploma qualified nurses alone will not address the health needs of a country. In addition to the need of improving quality patient care, the discipline and science of nursing needs advancement. Nurse researchers are needed to conduct research, disseminate research findings and translate knowledge in order to improve and advance nursing practice. Nursing scholarship can no longer be limited to nurse academics with masters and doctoral degrees; much rather is it the responsibility of every nurse working in a healthcare setting (Stockhausen & Turale, 2011). Research that addresses nursing practice provides examples of scholarship of discovery, which are further enhanced by the implementation of best practice guidelines (Robert & Pape, 2011). The scholarship of integration is evidenced by transfer of learning; thereby bridging the theory-practice gap. Improving current nursing practices in a systematic public way, which is open for evaluation and may represent the scholarship of application, is needed.

The heavy disease burden, high acuity of patients and technological advances in health science demand that nurses be educated to solve complex problems and make sound clinical judgements that are informed by best available evidence. Globally building research capacity in health services are of paramount importance in order to produce a sound evidence base for decision-making in both the policy and practise domains (Canadian Health Service Research Foundation, 2008). Researchers have found that generally, degree-qualified nurses have stronger leadership skills; they are more creative, critical and reflective and bring about change more often than lower-qualified nurses bring. Furthermore, graduates have a more systematic approach to information seeking, superior care planning, higher-quality nursing performance and they are more focused on continuity of care and outcomes (ANON., 2012 and Johnston, 2009).

In South Africa, the National Qualification Framework (NQF) sets different outcomes base on certain level descriptors (South African Qualification Authority (SAQA), 2012). These level descriptors stipulate that a diploma prepared nurse, who completes the diploma at NQF exit level 7, is expected to demonstrate integrated knowledge of a field of study. The degree prepared nurse that exit the program on a NQF level 8, should not only demonstrate knowledge, but also understand the theory. They must also understand and apply research methodologies as well as the methods and techniques relevant to the field. They must also apply such knowledge in a particular field; evaluate the knowledge as well as the processes of knowledge production (SAQA, 2012).

The world is looking towards combating the decline in nursing numbers with better-educated nurses, as patient safety and quality of care can be associated with the proportion of degree-prepared nurses at an institution (Aiken et al., 2014, Benner et al., 2010 and Johnston, 2009). Building research capacity, thus preparing graduate nurses to proceed to doctoral studies, is internationally recognised as an essential process to produce a sound evidence base for decision-making in policy and nursing practise (Canadian Health Service Research Foundation, 2008). Despite FUNDISA's (Forum of University Nursing Deans in South Africa) plea that South Africa needs to appreciate and develop its degree-educated workforce to improve the quality of healthcare (ANON 2012) the South African government is planning to address the health problem with more lower-cadre nurses and more diploma-prepared nurses (Zuma, 2011). The reasoning, according to Brier, Wildshut, and Mgqolozana (2009), is that too few school leavers qualify for university entrance each year and many students drop out. This strategy just emphasises what Benner et al. (2010) unequivocally says, "Unfortunately, the public, including the legislators and other policy makers, underestimate the preparation necessary for today's nurses."

Currently, fewer than 20% of South Africa's professional nurses are being trained through a four-year degree programme, while other African countries like Botswana, Mozambique, Malawi and Kenya are now moving towards a degree programme as an entry into the nursing profession (ANON 2012). PEPFAR through the Nursing Education Partnership Initiative (NEPI) and the World Health Organisation launched a major initiative for the up-scaling of transformative nursing education in Africa during 2010. Mulaudzi, Daniels, Direko, and Uys (2012) is of the opinion that not only should the quantity of health professionals increase but the quality of the professionals must be addressed.

3. Research problem

Recent legislation in South Africa (South Africa 2005) stipulates that professional nurses and midwives will be graduates from a four-year professional degree, while the majority of prospective nurses will enrol in a three-year diploma programme, exiting as generalists and staff nurses. This implies that the majority of nurses in South Africa will unfortunately lack preparation at graduate level. This might create certain reservations regarding the scholarship of nursing in the country, and nurses' ability to build and maintain a scientific competitive profession. Several authors (Bauer-Wu et al., 2006, Robert and Pape, 2011 and Stockhausen and Turale, 2011) categorically state that scholarship in nursing can no longer be charged to nurse academics, however the resent legislation in South Africa disable nurse clinicians to conduct research. Nurses in the practise field should be prepared at degree and postgraduate levels (masters' degree and doctoral level) to enable the clinical nurse experts to produce and apply knowledge via research in their field of expertise.

Contrary to global trends to raise the level of education of nurses, South Africa is moving towards a lower level of nursing education in an effort to increase the number of nurses. This decision might contribute to the poor quality of care, especially in view of the fact that poor quality healthcare can be ascribed to insufficient leadership and innovation (Harrison, 2010).

The question that arises is whether degree-prepared nurses in South Africa contribute to scholarly activities more often than do diploma-prepared nurses.

4. Research method and design

This article reports on a cross-sectional study, conducted to compare specific acts of scholarship between nurses who completed a four-year integrated diploma programme at nursing colleges in South Africa, with graduates who completed a four-year degree programme in nursing at universities (academic) or universities of technology.

The aim of the study was to establish whether degree prepared nurses partake in scholarly activities more often than diploma prepared nurses in order to describe how nurses can play a role and can be trained to produce a sound evidence base for decision-making in policy and nursing practise.

All respondents were practicing within the nursing profession in South Africa at the time of the study. The researcher(s) capitalised on the advantage of a cross-sectional design to obtain useful data in a relatively short time. A disadvantage is that generation effects may threaten the internal validity of the study (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). Because the age distribution of both groups was similar, the thread to the internal validity by the generation effect is diminished (Bordens & Abbott, 2008).

4.1. Population and sampling

The population were all professional nurses registered with the South African Nursing Council (SANC) who had obtained either a four-year university degree or a four-year integrated college diploma. At the time of sampling in 2010, the number of professional nurses registered with the SANC stood at 111 299. However, some of these nurses lived and worked abroad and furthermore, not all these registered nurses were practicing at that stage.

The statistician at the SANC compiled two sample frames; one for degree qualified nurses and another for diploma-qualified nurses. Sampling frames consisted of a numbered list of all 111 299 professional nurses (degree- and diploma-qualified) registered with the SANC. A 2.7% sample size was calculated. Rounded to a 1 000, the drawn sample comprised 3000 respondents, which showed equal representation of graduates and diplomats. The sample size was limited to 2.7% due to the high cost of postage and limited funding. A power analysis was not done due to the descriptive nature of the study. A statistician at the SANC randomly sampled equal numbers (1500) from both the numbered lists of graduates and of the diplomats, using computer software. All professional nurses who did bridging courses to proceed into their professional nursing careers as well as those older than 60 years were excluded from the study.

4.2. Validity and reliability

Data were gathered by means of a self-administered questionnaire that was based on current literature on scholarship in nursing practice. A panel of experts that consisted of a biostatistician, research experts, and people that are well versed in nursing scholarship, thus people considered "scholars", reviewed the draft questionnaire. They applied the criteria for coherency, continuity, navigational path, content and simplicity of language. The input from the review panel enhanced the face and content validity of the questionnaire. Open-end responses as well as response set questions were included in the questionnaire. All response set questions had an option where the participant could add data that were not included in the response set.

4.3. Pre-testing of the questionnaire

The principal researcher asked ten post graduate nursing students who were not included in the sample to participate in the pilot study. On completing the questionnaire, the researcher asked them to indicate any questions they found ambiguous and to suggest rephrasing. The researchers also noted how long it took the pilot group to complete the questionnaire and coded the questionnaire to enhance data capturing. Data of the pre-test were excluded from the main study because suggestions made by the pilot group were incorporated into the final questionnaire.

4.4. Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, granted ethical clearance. A cover letter, information leaflet, questionnaire and business service envelope were sent to the sample population. The cover letter invited respondents to complete the questionnaire voluntarily and anonymously while the information leaflet explained the purpose of and the research process. Ethical aspects such as confidentiality, anonymity, voluntariness and dissemination of results were addressed in the information leaflet. After six weeks, the researchers dispatched a second round of questionnaires to remind respondents to complete the questionnaire. Despite the reminder, the return rate was low at 16%. Due to lack of funding, the researchers did not consider another reminder.

4.5. Data analysis

Trained research assistants coded the questionnaires. The researchers did spot checks to ensure correctness of the coding on 10% of the completed questionnaires. Data capturers at the Information and Technology Services of the University of the Free State captured the data where after the bio-statistician did the analysis by means of the SAS™ programme. Due to the small sample size no comparative statistics was done.

5. Results

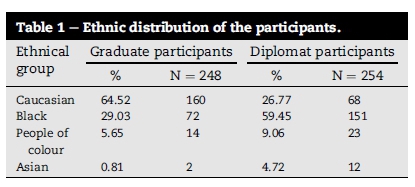

A sample of 3000 questionnaires were dispatched; 497 were returned even after a reminder was sent. The return rate of diplomat nurses was 258/1500 (17.2%) and that of graduate nurses was 248/1500 (16.45%). Graduate respondents (160 out of the 245 who participated, 64,52%) were Caucasian while the diplomat respondents comprised mostly of African people, people of colour, Indian and Asian people (see Table 1).

Respondents from all nine South African provinces took part in the study. The majority of diplomat respondents and graduate respondents who took part in the study were at that stage working as registered nurses in South African urban areas. Sixty-eight per cent (n = 174) of the diplomats worked in the public sector while graduate respondents seemed to be equally distributed between the public sector and the private sector at 51,14% in private and 48,86%% (n = 219) in the public sector respectively.

The age for the diplomats ranged from 26 to 54 with a median of 40 years while the age distribution of the graduates was between 23 and 57 years with 37years as the median. This is more or less on par with the average age of a registered nurse as it is 45 years in Canada and 41-45 years in Denmark, France, Iceland, Norway and Sweden (Letvak, Ruhm, & Gupta, 2013). Because the age distribution of both groups is similar, the thread to the internal validity by the generation effect is diminished (Bordens & Abbott, 2008).

Responses indicate that 46 (n = 46) respondents were nurse educators. Forty of them (86.96%) achieved a degree as first qualification opposed to the six respondents (13.04%) who achieved a diploma as first qualification. Eighteen of the nurse educators who obtained a degree as first qualification were in educator posts in the private sector, at universities, nursing colleges or in private hospital groups. All six nurse educators who had obtained a diploma as first qualification taught at public colleges of the National Department of Health or in training hospitals.

Out of 69 nurse managers, 41 (59.42%) had completed a degree in nursing as first qualification opposed to the 18 (26.08%) managers with diploma qualifications as the first qualification. Both diplomats and graduates indicated general nursing care as their primary responsibility, even where their job description indicated "nurse managers".

Of the 248 graduates, 126 were promoted between 2007 and 2011, while 79 out of 254 diplomat nursing respondents were promoted. It seemed that a degree qualification, where managerial skills and decision-making skills are on the forefront, provided the degree prepared respondent with a higher probability to be promoted (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2 highlights the trend that Graduate nurses further their career through formal education, which may have a beneficial effect on quality of care.

Respondents indicated that they based their practice on eight aspects as indicated in Fig. 3. 60.24% of the graduate nurses and 61.42% of the diploma-prepared nurses did continuous self-evaluation. It is of concern that 13% of the 46 nurse educators were not degree prepared. Hence these 13% nurse educators are ill equipped to teach research and supervise research projects. Furthermore, the nursing profession need educators and nurse experts at the bedside to be involved in knowledge generation.

The shortage in numbers of degree prepared nurses in clinical practice aligns with the 14.68% diploma-prepared respondents who initiated or were ever involved in research versus the 32.92% graduate nurses who initiated or were involved in research. More graduates (50.6%) than diplomats (37.8%) embarked on innovative practices. Fewer diploma prepared respondents (55.91%) than degree prepared respondents (62.25%) based their nursing practice on evidence and best practice guidelines.

Pertaining to the scholarship of discovery, as expected, the degree-prepared nurses' acts of scholarship exceeded those of the diploma-prepared nurses. Degree-prepared nurses contributed as co-authors of books (4.90%) or as authors of academic books (3.45%) and by publishing research articles (5.88%), delivering papers at conferences (21.3%), participating in research projects (31.13%) and actually initiating research (34.69%). Diploma-prepared nurses lacked largely in these acts as illustrated in Fig. 4, although they tended to attend conferences just as regularly as degree-prepared nurses.

6. Discussion

Doctors are a scarce commodity in rural areas where 144 respondents (58 graduates and 86 diplomats), participating in this study worked Therefore the critical thinking skills and the nurses' ability to make sound clinical decisions based on evidence and international best practices are important (ANON 2012). Clinton, Murrells, and Robinson (2005) also reason that primary healthcare systems need degree-qualified nurses who can reason clinically and make clinical judgements. Many international groups, such as governments, the military, nurse executives, healthcare foundations, nursing organisations and various practice settings advocate for an increase in the number of degree-prepared nurses to contribute to the scholarship of nursing and nursing practice (Aiken et al., 2014, ANON., 2012 and Johnston, 2009). South Africa therefore needs graduate nurses to work in rural areas as the nursing profession simply cannot afford that future nurses practise without a science to inform their decisions, and science will not be available without the preparation of nursing scholars to create it (Valiga & Ironside, 2012).

More of the diplomats (f = 86, 33%%) than graduates (f = 58; 23,38%) indicated that they worked in resource-poor environments. In resource-poor areas, the attributes of critical thinking, such as creativity, intellectual curiosity, problem solving and rational inquiry (Billings & Halstead, 2009) are essential. All the degree-prepared nurses who indicated that they work in resource-poor areas (58/58) found it possible to utilize these attributes by indicating that they adapted their practice according to circumstances. In the public healthcare sector in South Africa, nurses who can reason clinically and make clinical judgements are needed to ensure scholarship of integration, application as well as teaching and learning. South African graduate nursing curricula include exist level outcomes that aim to develop creative thinking, independent problem solving, professional skills, critical thinking, communication skills, teamwork, as well as lifelong learning of students that will develop evidence-based nursing practitioners (Biggs & Tang, 2011).

For various reasons, diploma graduates sometimes find it very difficult to further their studies to a degree level, and if they do so, it takes more time and it becomes more costly than to start with a degree as the first entry level into the profession (ANON., 2012 and Johnston, 2009). This lack of scholarship development may impact negatively on lifelong learning and professional development as well as the development of the nursing profession.

In the current study, almost double the number of professional nurses who obtained a nursing degree as first qualification worked at managerial level compared to those who obtained a diploma as first qualification. Due to the holistic approach of teaching and learning at university level, the focus is on the development of nursing management and leadership skills as defined in the exit level outcomes, according to SAQA (2012).

This study findings support Kumor's (2009) notion that degree prepared nurses are needed at the managerial level. This highlights the need for more degree qualified nurses because they are taken up in managerial and educational positions and do not stay at the bedside where they are really needed. Bedside nursing care are left to the lower cadres, contrary to what is happening globally where the degree qualified nurse with the reasoning skills to manage acute and ever changing challenges, are practising. Aiken et al. (2014) emphasise that reducing the number of nurses to save costs might adversely affect patient outcomes and that an increase in degree qualified nurses could reduce preventable hospital deaths.

The nursing profession therefore needs degree-prepared nurses who can review nursing practice and evidence through research to challenge inefficiencies and poor-quality nursing practice in financially constrained times (ANON 2012). Rauen, Flyn-Makic, and Bridges (2009) state that in clinical practice, nursing practice is more connected to tradition than to evidence-based practice, therefore the need for not only degree prepared nurses at education and managerial level but also at the bedside where better decision-making skills are needed (Clinton et al. 2005). Degree prepared nurse are needed in clinical practice to improve on research initiatives regarding best practices.

If nurses do not become involved with nursing education institutions where scholarship development is a core function and research is essential, the practice of nursing in South Africa and globally will deteriorate. It is therefore necessary that all cadres of nurses should upgrade their qualifications to attain all the different levels of scholarship and scholarly activities. At universities, nurses are not only educated to accept practice as it is, but also to question the way practice was done in the past. Equally important thus is to build disciplinary capacity for the scholarship of discovery (Valiga & Ironside, 2012). Degree-prepared nurses are equipped to become critical thinkers who would bring scientific evidence into play and transform traditional or "book" practice to evidence-based practice. Universities encourage nurses to get involved with research through post-graduate research and motivate these students to become true researchers who will do research in practice and publish research findings to inform practice.

7. Limitations of the study

The small differences between the degree qualified and diploma-qualified nurses with regard to activities related to scholarship may be due to the small sample size. Despite efforts to increase the number of respondents, the response rate remained low. Thus, generalizability of the findings is limited.

In South Africa the nursing education platform is changing drastically. Currently the diploma and degree programme is each a four year integrated programme and the students from both programmes are licenced by the SANC to practice as a generalist, community healthcare nurse, psychiatric nurse, and midwife. In future, this scenario is going to change with the degree programme being four years and rendering a nurse with a double qualification as professional nurse and midwife while the diploma programme will render a nurse with a single qualification after three years of training. This training framework may lead to a greater distinction between degree qualified and diploma-qualified nurses. A recommendation is to duplicate this study after the new framework has been implemented to determine if there is a clear distinction between the two categories.

8. Conclusion

Currently, in South Africa, the average acts of scholarship among graduate nurses are still low, but are markedly more than those of diploma-prepared nurses. The most evolving education is provided by universities where nursing research is done and scholarship development becomes a priority through higher education, under which these academic institutions function (Frick & Kapp, 2009). Although the difference in scholarly activities is not overwhelming, it was evident from the research that nurses who had obtained a degree as first qualification were the ones who were still involved with scholarly activities.

If nursing is to regain and maintain its professional independence and uniqueness it must promote the science of nursing and nursing as a science. This can only be achieved by increasing the scientists within the profession and making what to some (Shabalala-Msimang RIP) see as "household" into what it is and has been - the Profession of Nursing.

International trends and research show the importance of baccalaureate education in relation to patient outcomes; however, nurses remain the least educated of all health professionals (Johnston, 2009). This, despite the fact that nursing is in the privileged position to educate caring scientists. The situation in South Africa will became even worse if the South African government tries to solve the health crisis by merely producing more nurses and neglecting or even discarding graduate nursing studies.

The development of research capacity, in other words degree-prepared nurses who can continue to master's and doctoral level, extends beyond the development of the individual's research skills to the support of teams, networks, institutions and systems (Canadian Health Service Research Foundation, 2008). South Africa, like the rest of the world, needs to increase the number of nurses, and support degree education to enhance scholarship of the nursing profession. Nurse specialists are needed in practice so that research do not imply taking well educated people away from clinical practice, but use them to build theory and generate knowledge in the clinical practice.

Recognition

The authors would like to give recognition for Me. M. Nel from the Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State for overseeing data capturing and providing statistical assistance for this project. We also acknowledge Mrs Nora Olivier for assisting with the sampling process and Prof Magda Mulder, Dr Lily van Rhyn as well as Mrs Ilse Searle who acted as critical readers.

The project was funded by the University-based Nursing Education South Africa Programme (UNEDSA) that funded the School of Nursing, as part of an initiative of the Atlantic Philanthropies. The generous grant from Atlantic Philanthropies enabled the School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of the Free State to establish a rich technological teaching and learning environment.

Research significance

In South Africa the Government discourage or even discard the training of nurses on a graduate level. To ensure theory development and knowledge generation through research, graduate nurses need to be trained.

Author contributions

LR and YB were responsible for the project design as well as the instrument development. LR wrote the manuscript with inputs from B. CG was responsible for the literature searches and calculations.

References

Aiken, L. H., Sloane, D. M., Bruneel, L., et al. (2014). Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet, 13, 62631e62638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-673. [ Links ]

ANON. (2012). Trends in nursing 2012. Pretoria: FUNDISA. [ Links ]

Bauer-Wu, S., Epshtein, A., & Ponte, P. R. (2006). Promote excellence in nursing research and scholarship in the clinical setting. Journal of Nursing Administration, 36(5), 224e227. [ Links ]

Beach, D. (2002). Professional knowledge and its impact on nursing practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 2(2), 80e86. [ Links ]

Benner, P., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., & Day, L. (2010). Educating nurses.Acall for radical transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university (4th ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education. [ Links ]

Billings, D. M., & Halstead, J. A. (2009). Teaching in nursing: A guide for faculty (3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. [ Links ]

Bordens, K. S., & Abbott, B. B. (2008). Research design and methods: A process approach (7th ed). New york: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Brier, M., Wildshut, A., & Mgqolozana, T. (2009). Nursing in a new era: The profession and education of nurses in South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC press. [ Links ]

Canadian Health Service Research Foundation (CHSRF). (2008). Nursing research in Canada: A status report. viewed 21 February 2012, from http://www.canr.ca/documents/NursingResCapFinalReport_ENG_Final.pdf. [ Links ]

Clinton, M., Murrells, T., & Robinson, S. (2005). Assessing competency in nursing: A comparison of nurses prepared through degree and diploma programme. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14(1), 82e94. [ Links ]

Frick, L., & Kapp, C. (2009). The professional development of academics in pursuit of scholarship. In E. Bitzer (Ed.), Higher education in South Africa (pp. 255e282). Stellenbosch: SUN Media. [ Links ]

Glassick, C. (2000). Boyer's expanded definitions of scholarship, the standards for assessing scholarship and the elusiveness of the scholarship of teaching. Academic Medicine, 75(9), 877e880. [ Links ]

Harrison, D. (2010). An overview of health and healthcare in South Africa 1994e2010: Priorities, progress and prospects for new gains. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. viewed 14 February 2012, from www http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/reports/2010/overview1994-2010.pdf. [ Links ]

Johnston, K. (2009). The importance of the baccalaureate degree in nursing education. Peoria Magazines. viewed 21 February 2012, from http://www.peoriamagazines.com/ibi/2009/apr/importance-baccalaureate-degree-nursing-education. [ Links ]

Kumor, M. (2009). Difference between degree and diploma. viewed 12 March 2015, from http://www.differencebetween.net/business/difference-between-degree-and-diploma/. [ Links ]

Letvak, S., Ruhm, C., & Gupta, S. (2013). Differences in health, productivity and quality of care in younger and older nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 21(7), 914e921. [ Links ]

Mulaudzi, F. M., Daniels, F. M., Direko, K. K., & Uys, L. R. (2012). The current status of the education and training of nurse education in South Africa. The trends of nursing, 1(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.14804/1-1-26. [ Links ]

Rauen, C. A., Flyn-Makic, B. M., & Bridges, E. (2009). Evidencebased practice habits: Transforming research into bedside practice. Critical Care Nurse, 29(2), 46e59. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. (2005). Nursing Act No. 33. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Robert, R. R., & Pape, T. M. (2011). Scholarship in nursing: Not an isolated concept. Medsurg Nursing: Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses, 20(1), 41e44. [ Links ]

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). (2012). Government Gazette no 35548 of 27 July 2012, level descriptors for the South African national qualifications framework. viewed 13 April 2015, from www.greengazette.co.za/.../national-gazette-35547-of-27-July-2012-vol-565_20120727-GGN-35547.pdf. [ Links ]

Stockhausen, L., & Turale, S. (2011). An explorative study of Australian nursing scholars and contemporary scholarship. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(1), 89e96. [ Links ]

Swindells, C., & Willmott, S. (2003). Degree vs Diploma education: Increased value to practice. British Journal of Nursing, 12(18), 1096e1104. [ Links ]

Valiga, M., & Ironside, P. (2012). Crafting a national agenda for nursing education research. Journal of Nursing Education, 51(1), 3e4. [ Links ]

Zuma, J. (2011). SA healthcare in for a makeover. viewed 11 March 2013 from http://southafrica.info/about/government/statenation2011g.htm. [ Links ]

Received 22 July 2015

Accepted 12 August 2016

Available online 6 October 2016

Peer review under responsibility of Johannesburg University.

E-mail address: roetsl@unisa.ac.za (L. Roets).

* Corresponding author.