Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.21 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.01.002

FULL LENGTH ARTICLE

Violence against nurses in the southern region of Malawi

Chimwemwe Kwanjo BandaI, a; Pat MayersII, *; Sinegugu DumaII, b

IUniversity of Cape Town, University of Malawi, Kamuzu College of Nursing, Malawi

IIDivision of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: To investigate and describe the nature and extent of violence against nurses and the perceived effects thereof on nurses in the southern region of Malawi.

METHODS: A descriptive, cross-sectional study in which 190 questionnaires were sent out to nurses from five facilities, 112 were returned completed (60% response rate). The five facilities included two central hospitals, one psychiatric hospital and two health care centres

RESULTS: 86% of the respondents agreed that violence against nurses is a problem in Malawi. The prevalence of violence for the five facilities in the preceding 12 months was 71% (CI 61%-79%) and was highest at the psychiatric hospital (100%). The types of violence experienced include verbal abuse (95%), threatening behaviours (73%), physical assaults (22%), sexual harassments (16%) and other (3%). Perpetrators of violence were: patients (71%); patients' relatives (47%); and work colleagues (43%). Nurses reacted to incidents of violence by reporting to managers, telling their friends, crying, retaliating, or ignoring the incident. Most (80%) nurses perceived that violence has psychological effects on them, which consequently affects their work performance and make them lose interest in the nursing profession.

CONCLUSIONS: Workplace violence against nurses exists in Malawi and it affects nurses psychologically; may result in poor work performance; and may be a causative factor in the attrition of nurses from the nursing profession. The study recommends that health facilities should adopt policies aimed at minimizing violence against nurses to create motivating and safe working environment for nurses.

Keywords: Violence; Nurses; Malawi; Workplace violence

1. Introduction and background

Violence in the health sector has become a global concern in the 21st century (Needham et al., 2008). The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines workplace violence as "incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health" (WHO, 2010, p. 1). Four categories of perpetrators of violence in the health sector workplace have been identified.

• Type I: (Criminal Intent): The perpetrator has no relationship to the workplace.

• Type II: (Client or Customer): The perpetrator is a client at the workplace who becomes violent or aggressive toward a staff member or another client.

• Type III: (Worker-to-Worker): The perpetrator is a staff member or past staff member of the workplace, including managers, workers, physicians, contracted staff or service workers and volunteers.

• Type IV: (Personal Relationship): The perpetrator is a person with a relationship to a staff member who becomes violent or aggressive toward that staff member in the workplace (e.g. domestic violence) (Registered Nurses'Association of Ontario, 2009).

On average, nurses are three times more at risk than other occupational groups to experience violence in the workplace (WHO, 2010). Violence against nurses has been reported in most types of health care facilities, correctional services health settings, community and maternity settings. Nurses are the most likely of all health care workers to experience violence or be assaulted (National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice, 2007). Few nurses have not witnessed or been exposed to violence and aggression in their everyday work experiences.

2. Literature review

A literature search was conducted for studies published since 2000, using the search terms workplace violence, health sector violence and violence against nurses. Workplace violence against nurses has been reported over the last decade in most regions of the world. Studies from a number of countries have been reported: European Union: Italy (Ramacciati, Ceccagnoli, & Addey, 2015), Germany (Franz, Zeh, Schablon, Kuhnert, & Nienhaus, 2010), Turkey (Kamchuchat et al., 2008 and Senuzun Ergun and Karadakovan, 2005), Asia: Thailand (Kamchuchat et al., 2008), Taiwan (Shiao et al., 2010), Hong Kong (Kwok et al., 2006), China (Jiao et al., 2015); the Middle East: Israel (Natan, Hanukayev, & Fares, 2011), Palestine (Kitaneh & Hamdan, 2012), Jordan (Al-Omari, 2015); Africa: South Africa (Khalil, 2009), Egypt (Abbas, Fiala, Abdel Rahman, & Fahim, 2010) and Australia (Hegney, Tuckett, Parker, & Eley, 2010) and the United States of America (Gates, Gillespie, & Succop, 2011). Differences in prevalence from country to country could be due to factors such as: setting; work load; working style; and attitudes to reporting the event by the victims (Kamchuchat et al., 2008). The use of different time frames in reporting prevalence of workplace violence in surveys makes it difficult to compare violence against nurses from study to study (Taylor & Rew, 2011), e.g. the preceding week (Roche, Diers, Duffield, & Catling-Paull, 2010), the preceding three months (Hegney, Eley, Plank, Buikstra, & Parker, 2006), the preceding six months (Shiao et al., 2010) or twelve months (Abbas et al., 2010).

Workplace violence against nurses is categorised broadly into physical violence (assault, aggressive behaviour) or psychological violence (verbal abuse, stalking, sexual harassment) (Celik et al., 2007, Taylor and Rew, 2011 and Xing et al., 2015). The use of terminologies pertaining to the classification of violence varies, which makes comparisons and generalisation difficult. Psychological violence occurs more often than physical violence (Celik et al., 2007 and Kwok et al., 2006). Verbal aggression is the most common form of psychological violence against nurses (Abe and Henly, 2010, Celik et al., 2007, Khalil, 2009 and Shields and Wilkins, 2009). Sexual harassment of nurses has not been reported as much as other forms of violence (Kamchuchat et al., 2008 and Kwok et al., 2006).

Exposure of nurses to specific types of violence varies by world region. In a review of nurses' exposure to violence, Spector, Zhou, and Che (2014) reported that the Anglo region has the highest rates of physical and sexual harassment and the highest rates of bullying, emotional and verbal violence are reported from the Middle East. The risk of violence appears to be greater in psychiatric facilities, aged care facilities and emergency departments (Bilgin, 2009, Hegney et al., 2006, Kwok et al., 2006 and Taylor and Rew, 2011). In elderly care and psychiatric settings, the perpetrators of most incidents of violence against nurses are patients, although it should be noted that such violence may be unintentional, related to confusion or psychosis (Hegney et al., 2006, Kwok et al., 2006, Mullan and Badger, 2007 and Shiao et al., 2010).

Another common source of violence against nurses are patients' visitors and relatives (Campbell et al., 2011, Esmaeilpour et al., 2011 and Kamchuchat et al., 2008). Other reported perpetrators of workplace violence against nurses are fellow nurses, nursing management, other managers, doctors, and allied health professionals (Hegney et al., 2006, Kamchuchat et al., 2008 and Yildirim and Yildirim, 2007). The most common form of inter-colleague violence is bullying (Abe and Henly, 2010, Bennett and Sawatzky, 2013, Johnson and Rea, 2009 and Khalil, 2009).

The causes of workplace violence are varied. Direct patient condition/illness related causes include severe head injury, cognitive dysfunction and confusion, dementia, substance abuse and developmental delay (Kamchuchat et al., 2008 and May and Grubbs, 2002). Other reported causes relate to long waiting times and the enforcement of hospital policies such as the minimum number of visitors permitted at a patient's bedside and general frustration with the health care delivery system (May & Grubbs, 2002).

Most incidents of workplace violence against nurses go unreported (Esmaeilpour et al., 2011, Farrell et al., 2006, Kwok et al., 2006 and Senuzun Ergun and Karadakovan, 2005). Possible causes for underreporting include that such reporting may be considered as poor performance, that persons who report risk losing their jobs, and the possibility that in the case of patient -nurse assault, the nurse was perceived as being responsible for aggravating the patient action (National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice, 2007). It is however important to mitigate workplace violence due to its psychological and physical effects on the nurses (Franz et al., 2010). Workplace violence also affects the work morale of nurses there by compromising the quality of nursing care rendered to their clients (Celik et al., 2007, Franz et al., 2010, McKinnon and Cross, 2008 and Roche et al., 2010). Workplace violence is reported to affect recruitment and retention of nurses (Chen et al., 2013 and King and McInerney, 2006).

The extent of violence against nurses and how it affects nurses in Malawi is not well documented and most information is anecdotal.

3. Aim of the study

The aim of the study was to investigate and describe the nature of and extent of violence against nurses and the perceived effects thereof in selected health facilities in the southern region of Malawi.

3.1. Objectives

• To determine the extent of violence against nurses in five health facilities in the southern region of Malawi.

• To describe types of violence directed against nurses in each of the settings.

• To identify the perpetrators of workplace violence against nurses.

• To describe the perceived effects of violence on nurses' professional and personal lives.

4. Research design and method

A descriptive, cross-sectional survey design was used as a baseline for further in depth studies. Recall bias is a limitation in this retrospective study as respondents were asked to recall events that occurred in the past twelve months.

4.1. Population and sampling

The study population comprised nurses working in the five government health facility sites in the southern region of Malawi. The facilities comprised two central hospitals, two health centres and one psychiatric hospital. The two central hospitals are large tertiary government funded teaching hospitals providing health care at all levels. The health care centres provide care at primary level for adults and children as well as maternity services. The psychiatric hospital provides tertiary level mental health services. An estimated 430 nurses were working in these facilities at the time of data collection.

A non-probability sampling technique was used in the larger facilities and all the nurses working in the smaller facilities were included. Although this sampling technique does not ensure equal opportunity of selection, it was the most appropriate in three of the smaller facilities as the number of nursing personnel was limited; therefore probability sampling would have reduced the number of possible participants. The aim was to provide all the nurses working in the smaller facilities with a questionnaire. Nurses who were on duty during the data collection period were included in the study.

4.2. Data collection

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire, adapted from two instruments developed by Khalil (2009) and Kwok et al. (2006) for the assessment of violence against nurses. The questionnaire gathered information on the following areas: demographic information of the respondents, nature of violent incidents observed or experienced, time of day or week when violence was most likely to occur, characteristics of perpetrators, reporting of incidents and effects of violence on respondents' personal and professional lives. The 21-item self-administered questionnaire comprised structured questions, Likert scales, rank order and open-ended questions. The questionnaire was provided in English only, as the medium of instruction and formal health sector communication in Malawi is English. The information letter was available in English and the local language Chichewa.

Data were collected over a two-month period in 2011. At each facility, trained research assistants approached potential respondents and sought their consent to participate. Those who agreed to participate were given the questionnaire and asked to return the completed questionnaire in a designated box within three weeks.

4.3. Reliability and validity

To ensure reliability and validity, two lecturers at a college of nursing in Malawi were requested to review the questionnaire for relevance and whether the questions addressed the aims and objectives of the study. A pilot study was conducted with a group of ten nursing students at a nursing college in the southern region of Malawi. These students were taking an upgrade course from enrolled nursing to professional nurse qualification, and had experience working in one of the identified facilities or a similar facility. Suggested changes with respect to the clarity of questions and time required to complete the questionnaire were incorporated into the final version of the questionnaire, which was again tested with five Malawian registered nurses studying at the University of Cape Town.

4.4. Data management and analysis

The data were entered in the EpiData statistical package then imported into Stata version 11 for analysis. One hundred ninety (190) questionnaires were distributed and 155 were returned, of which 112 were completed and had usable data. These were considered for analysis and gave an overall response rate of 60%.

Raw data from each completed questionnaire were entered into Epidata for analysis. All closed or structured questions of the questionnaire were assigned numeric codes. Open-ended questions that elicited string variables (word or sentence answers) were also entered in the spreadsheet and were analysed using content analysis. Descriptive and non-parametric statistics were used. For each variable, frequency and percentage was calculated. Where variables were suspected to relate, cross-tabulations were done and tests for significance of the relationship were applied.

4.5. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and the National Health Sciences Research Committee at the Ministry of Health in Malawi. In respecting the autonomy of the respondents, participation in the study was voluntary and all information obtained was anonymous and/or confidential. Written consent was obtained and confidentiality and anonymity were assured through replacing names with codes for the five study sites and respondents. Minimal risk for the participants was assumed, and there was no compromise with respect to patient care as participants were allowed to complete the questionnaire in their own time. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, October 2008).

5. Results

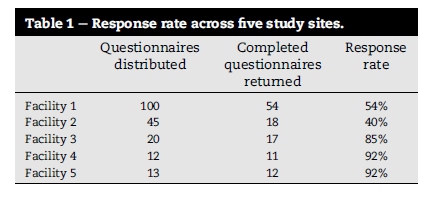

The response rate varied across individual facilities as follows (Table 1).

The respondents comprised three main categories of nurses, further divided into eleven sub-categories: Registered Nurses (university degree/diploma nursing programme with four sub-categories) (37.5%), Enrolled Nurses (certificate programme with five sub-categories) (33.93%) and Nurse Midwife Technicians (three-year training programme with two sub-categories) (28.57%) working in various clinical areas and departments. The female: male ratio was 77%: 23%. The nurses had a varying range of work experience with 62.5% having practised as nurses for ten years or less, and 37.5% with a work experience of more than ten years. The average duration of working in a department was 4.5 years, with a minimum duration of one year and a maximum duration of 25 years.

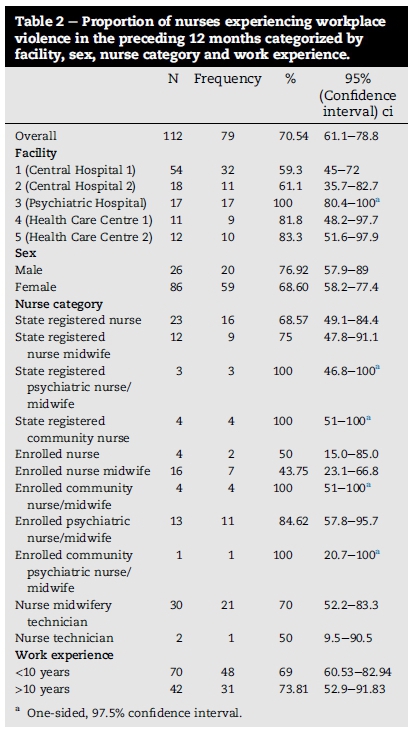

The overall prevalence of violence across the five facilities was 70.54%. Table 2 is a summary of the prevalence of violence in the preceding 12 months. There was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of workplace violence according to sex, category of nursing and work experience.

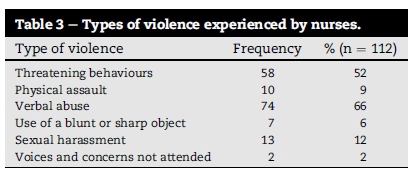

Seventy-nine of the 112 respondents reported that they had experienced violence in the preceding twelve months. Table 3 presents the most common reported forms of violence that the nurses experienced. Some respondents experienced more than one form of violence in the preceding twelve months; therefore, the frequency of incidents of violence is higher than the number of respondents.

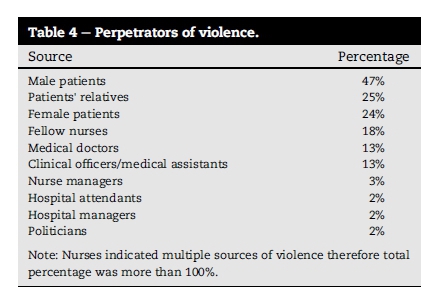

Patients' relatives and male patients were the main perpetrators of violence against the nurses. Table 4 summarizes the reported perpetrators of violence against nurses.

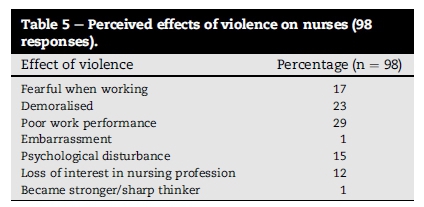

The majority of the respondents (87.5%) felt that workplace violence had an effect on their personal and/or professional lives regardless of whether or not they personally had experienced violence. The common perceived effect of workplace violence on the nurses was that it leads to demoralisation and poor work performance by the nurses (Table 5).

6. Discussion

The prevalence of 70.54% found in this study is similar to other studies. In a Hong Kong study, Kwok et al. (2006) reported a 76% prevalence of violence over a 12-month period and a study in Taiwan reported 81.5% prevalence of workplace violence over a similar period (Chen et al., 2013). High rates of violence against nurses worldwide have been attributed to the predominance of women in the nursing profession, who generally have a more submissive character (Ferns, 2006 and Kwok et al., 2006). In Malawi, 75% of the nurses are females (WHO, 2006). Traditional norms in the country expect women to be gentle and submissive which could make the nurses vulnerable to being victims of workplace violence from various sources.

All forms of violence were significantly higher at the psychiatric facility which is consistent with findings by Bilgin (2009) in Turkey, Maguire and Ryan (2007) in Ireland, and Franz et al. (2010) in Germany. Most violent incidents in psychiatric facilities were perpetrated by patients, attributed primarily to confusion (May and Grubbs, 2002 and Mullan and Badger, 2007). Male patients were reported to have perpetrated more incidents of violence against nurses than female patients.

In the central hospitals, as compared to the psychiatric hospital and community health care centres, patients were not perceived to be the main sources of violence. Patients in the central hospitals are admitted with serious illness conditions and for the most part the risk of violence is limited. Reported perpetrators of violence against nurses in central hospitals were work colleagues (medical doctors, nurses, clinical officers, and medical assistants) and hospital management staff (administrators, accountants and human resource officers) and this is consistent with findings from other studies (Abbas et al., 2010, Hegney et al., 2006 and Yildirim and Yildirim, 2007). Violence against nurses by other health care professionals is attributed to differences in professional values that cause conflict and can result in violence (Strandmark & Hallberg, 2007).

Psychological violence in the form of verbal abuse was the most common form of violence reported by nurses in all departments and this is consistent with findings from other studies (Abe and Henly, 2010, Celik et al., 2007, Khalil, 2009 and Shields and Wilkins, 2009). The prevalence of sexual harassment in this study was relatively low (16.46%), however it may be higher than reported probably because of fear of stigmatisation and the psychological effect of the event (Kamchuchat et al., 2008). Demir and Rodwell (2012) reported that verbal sexual harassment is linked to increased psychological distress levels. Despite the low reported prevalence of sexual harassment, this form of violence has detrimental physical and psychological effects on the victims and thus cannot be ignored.

Most incidents of sexual harassment occurred in the psychiatric hospital, but no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of sexual harassment by facility was found. Female and male nurses reported experiences of sexual harassment. In all cases of reported sexual harassment, the perpetrators were of the opposite sex to the victim.

The majority (62%) of respondents who had experienced a violent incident had reported the issue to a senior person or a manager. This is in contrast to findings from other studies where the majority of incidents of violence against nurses go unreported (Esmaeilpour et al., 2011, Farrell et al., 2006, Kwok et al., 2006 and Xing et al., 2015). The reason for the high reporting in the current study may be that those incidents were viewed as intentional and were perpetrated by patients' visitors or work colleagues and not patients. Nurses tend not to report incidents of violence if they perceive that the perpetrator lacked intent such as when the perpetrator appears confused (Chen et al., 2013, Kitaneh and Hamdan, 2012 and Luck et al., 2008).

Talking with a colleague is a common action taken by nurses following an experience of workplace violence; nurses also may respond to violence by taking some time off; seeking a transfer or retirement from the facility; and refusing to work with the violent patients (Farrell et al., 2006 and Kwok et al., 2006). Some (n = 12) respondents reported loss of interest in nursing and had considered leaving the profession as a consequence of workplace violence. Previous studies have reported that nurses who had been victims of violence resort to leaving their job (Farrell et al., 2006, King and McInerney, 2006 and Yildirim and Yildirim, 2007).

Violence affects all nurses regardless of whether they personally experienced an act of violence or not. Respondents were asked to explain how they were affected by the experiences of violence. The effects described were all of a psychological nature. These included poor work performance, demoralisation and fear, effects also reported in other studies (Kitaneh and Hamdan, 2012, Magnavita and Heponiemi, 2011 and National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice, 2007). This suggests that violence against nurses can have an impact on the quality of care rendered to patients. Roche at al. (2010) reported that an increase in violence against nurses resulted in an increase in medication errors and patient falls.

7. Conclusions, limitations and recommendations

The study has identified the existence of violence against nurses in the five facilities in Malawi. Workplace violence affects nurses psychologically and physically, may result in poor work performance; and may be a causative factor in the attrition of nurses from the nursing profession. The main limitations of the study are that it was conducted over a two-month period, limited to one region in Malawi and utilised a non-probability sampling technique. The results therefore cannot be generalised to all Malawian nurses. The study achieved a response rate of 60%. Although this is an acceptable response in a survey, it cannot be assumed that the non-responders would have been similar. Although the study elicited information regarding effects of workplace violence on the nurses, it cannot be concluded that there is a cause-effect as the research was cross-sectional could not establish causation.

The study therefore recommends that all health facilities should adopt a "violence free policy". In addition, there should be policies on reporting violence, provision of support for victims where necessary and management of perpetrators. Reported acts of violence should be analysed to identify causation and to plan for minimising the risks of violence. In known high-risk areas, training of nurses and other health workers to reduce risk and manage violent incidents should be included in orientation and in service training. There is need for further research with a larger sample and more health facilities to examine the risk factors for violence and to develop and evaluate strategies of reducing violence against nurses.

Authors' contributions

Research design: C Banda; P Mayers, S Duma

Data collection: C Banda

Data analysis and interpretation: C Banda; P Mayers

Reporting of data and drafting of article: C Banda; P Mayers

Review of data, amendments to article drafts and final approval: C Banda; P Mayers, S Duma

References

Abbas, M. A., Fiala, L. A., Abdel Rahman, A. G., & Fahim, A. E. (2010). Epidemiology of workplace violence against nursing staff in Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 85(1e2), 29e43. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21073846. [ Links ]

Abe, K., & Henly, S. J. (2010). Bullying (ijime) among Japanese hospital nurses: modeling responses to the revised negative acts questionnaire. Nursing Research, 59(2), 110e118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181d1a709. [ Links ]

Al-Omari, H. (2015). Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in Jordan. International Nursing Review, 62(1), 111e118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/inr.12170. [ Links ]

Bennett, K., & Sawatzky, J.-A. V. (2013). Building emotional intelligence: a strategy for emerging nurse leaders to reduce workplace bullying. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 37(2), 144e151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0b013e318286de5f. [ Links ]

Bilgin, H. (2009). An evaluation of nurses' interpersonal styles and their experiences of violence. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(4), 252e259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840802710464. [ Links ]

Campbell, J. C., Messing, J. T., Kub, J., Agnew, J., Fitzgerald, S., Fowler, B., et al. (2011). Workplace violence: prevalence and risk factors in the safe at work study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53(1), 82e89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182028d55. [ Links ]

Celik, S. S., Celik, Y., Agirbas, I., & Ugurluoglu, O. (2007). Verbal and physical abuse against nurses in Turkey. International Nursing Review, 54(4), 359e366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ j.1466-7657.2007.00548.x. [ Links ]

Chen, K.-P., Ku, Y.-C., & Yang, H.-F. (2013). Violence in the nursing workplace - a descriptive correlational study in a public hospital. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(5/6), 798e805. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04251.x. [ Links ]

Demir, D., & Rodwell, J. (2012). Psychosocial antecedents and consequences of workplace aggression for hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 44(4), 376e384. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01472.x. [ Links ]

Esmaeilpour, M., Salsali, M., & Ahmadi, F. (2011). Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. International Nursing Review, 58(1), 130e137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00834.x. [ Links ]

Farrell, G. A., Bobrowski, C., & Bobrowski, P. (2006). Scoping workplace aggression in nursing: findings from an Australian study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(6), 778e787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03956.x. [ Links ]

Ferns, T. (2006). Under-reporting of violent incidents against nursing staff. Nursing Standard, 20(40), 41e45. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16802588. [ Links ]

Franz, S., Zeh, A., Schablon, A., Kuhnert, S., & Nienhaus, A. (2010). Aggression and violence against health care workers in Germany- a cross sectional retrospective survey. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-51. [ Links ]

Gates, D. M., Gillespie, G. L., & Succop, P. (2011). Violence against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nursing Economics, 29(2), 59e66. [ Links ]

Hegney, D., Eley, R., Plank, A., Buikstra, E., & Parker, V. (2006). Workplace violence in Queensland, Australia: the results of a comparative study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12(4), 220e231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00571.x. [ Links ]

Hegney, D., Tuckett, A., Parker, D., & Eley, R. (2010). Workplace violence: differences in perceptions of nursing work between those exposed and those not exposed: a cross-sector analysis. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(2), 188e202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01829.x. [ Links ]

Jiao, M., Ning, N., Li, Y., Gao, L., Cui, Y., Sun, H., et al. (2015). Workplace violence against nurses in Chinese hospitals: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 5(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006719.e006719ee006719. [ Links ]

Johnson, S. L., & Rea, R. E. (2009). Workplace bullying: concerns for nurse leaders. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(2), 84e90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e318195a5fc. [ Links ]

Kamchuchat, C., Chongsuvivatwong, V., Oncheunjit, S., Yip, T. W., & Sangthong, R. (2008). Workplace violence directed at nursing staff at a general hospital in southern Thailand. Journal of Occupational Health, 50(2), 201e207. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18403873. [ Links ]

Khalil, D. (2009). Levels of violence among nurses in Cape Town public hospitals. Nursing Forum, 44(3), 207e217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00144.x. [ Links ]

King, L. A., & McInerney, P. A. (2006). Hospital workplace experiences of registered nurses that have contributed to their resignation in the Durban metropolitan area. Curationis, 29(4), 70e81. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17310747. [ Links ]

Kitaneh, M., & Hamdan, M. (2012). Workplace violence against physicians and nurses in Palestinian public hospitals: a crosssectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-469, 469e469. [ Links ]

Kwok, R. P., Law, Y. K., Li, K. E., Ng, Y. C., Cheung, M. H., Fung, V. K., et al. (2006). Prevalence of workplace violence against nurses in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 12(1), 6e9. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16495582. [ Links ]

Luck, L., Jackson, D., & Usher, K. (2008). Innocent or culpable? Meanings that emergency department nurses ascribe to individual acts of violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(8), 1071e1078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01870.x. [ Links ]

Magnavita, N., & Heponiemi, T. (2011). Workplace violence against nursing students and nurses: an Italian experience. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(2), 203e210. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01392.x. [ Links ]

Maguire, J., & Ryan, D. (2007). Aggression and violence in mental health services: categorizing the experiences of Irish nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(2), 120e127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01051.x. [ Links ]

May, D. D., & Grubbs, L. M. (2002). The extent, nature, and precipitating factors of nurse assault among three groups of registered nurses in a regional medical center. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 28(1), 11e17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/men.2002.121835. [ Links ]

McKinnon, B., & Cross, W. (2008). Occupational violence and assault in mental health nursing: a scoping project for a Victorian mental health service. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17(1), 9e17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00499.x. [ Links ]

Mullan, B., & Badger, F. (2007). Aggression and violence towards staff working with older patients. Nursing Standard, 21(27), 35e38. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17390944. [ Links ]

Natan, M. B., Hanukayev, A., & Fares, S. (2011). Factors affecting Israeli nurses' reports of violence perpetrated against them in the workplace: a test of the theory of planned behaviour. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 17(2), 141e150. [ Links ]

National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice. (2007). Violence against nurses. An assessment of the causes and impacts of violence in nursing education and practice (Retrieved from Washington). [ Links ]

Needham, I., Kingma, M., O'Brien, P. L., McKenna, K., Turker, E., & Oud, N. (2008). In Proceedings of the first international conference on workplace violence in health sector, together creating a safe work environment. Amsterdam: Dwingeloo and Oud Consultancy. [ Links ]

Ramacciati, N., Ceccagnoli, A., & Addey, B. (2015). Violence against nurses in the triage area: an Italian qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing, 23(4), 274e280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2015.02.004. [ Links ]

Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario. (2009). Preventing and managing violence in the workplace. Toronto, Canada: Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario. Retrieved from http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Preventing_and_Managing_Violence_in_ the_Workplace.pdf. [ Links ]

Roche, M., Diers, D., Duffield, C., & Catling-Paull, C. (2010). Violence toward nurses, the work environment, and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(1), 13e22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01321.x. [ Links ]

Senuzun Ergun, F., & Karadakovan, A. (2005). Violence towards nursing staff in emergency departments in one Turkish city. International Nursing Review, 52(2), 154e160. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00420.x. [ Links ]

Shiao, J. S., Tseng, Y., Hsieh, Y. T., Hou, J. Y., Cheng, Y., & Guo, Y. L. (2010). Assaults against nurses of general and psychiatric hospitals in Taiwan. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 83(7), 823e832. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0501-y. [ Links ]

Shields, M., & Wilkins, K. (2009). Factors related to on-the-job abuse of nurses by patients. Health Reports, 20(2), 7e19. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19728581. [ Links ]

Spector, P. E., Zhou, Z. E., & Che, X. X. (2014). Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(1), 72e84. [ Links ]

Strandmark, M., & Hallberg, L. R. (2007). The origin of workplace bullying: experiences from the perspective of bully victims in the public service sector. Journal of Nursing Management, 15(3), 332e341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00662.x. [ Links ]

Taylor, J. L., & Rew, L. (2011). A systematic review of the literature: workplace violence in the emergency department. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(7e8), 1072e1085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03342.x. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation. (2006). Health workforce demographics. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/globalatlas/docs/HRH/HTML/Age_ctry.htm. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation. (2010). What is workplace violence?. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/workplace/ background/en/index.html. [ Links ]

World Medical Association. (October 2008). Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. In 59th WMA general assembly, Seoul. [ Links ]

Xing, K., Jiao, M., Ma, H., Qiao, H., Hao, Y., Li, Y., et al. (2015). Physical violence against general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One, 10(11), 1e14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142954. [ Links ]

Yildirim, A., & Yildirim, D. (2007). Mobbing in the workplace by peers and managers: mobbing experienced by nurses working in healthcare facilities in Turkey and its effect on nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(8), 1444e1453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01814.x. [ Links ]

Received 13 July 2015

Accepted 15 January 2016

Available online 5 October 2016

Peer review under responsibility of Johannesburg University.

E-mail addresses: joychikoko@yahoo.co.uk (C.K. Banda), Pat.mayers@uct.ac.za (P. Mayers), Sinegugu.duma@uct.ac.za (S. Duma).

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +27 0214066464; +27 0824672302 (mobile).

a Tel.: +265 1873623, +265 884711313 (mobile).

b Tel.: +27 0214066321.