Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.21 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.08.001

FULL LENGTH ARTICLE

Mental health nurses' attitudes toward self-harm: Curricular implications

David G. ShawI; Peter Thomas SandyII, *

IBuckinghamshire New University, Reader in Health Psychology, Department of Psychology, Queen Alexandra Road, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, UK

IIUniversity of South Africa, Department of Health Studies, 6-184 Theo van Wyk, Muckleneuk Ridge, Pretoria, 0003, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Self-harm is an old problem but increasing in incidence. It has important consequences for the individual concerned, the health care system, and can impact the well-being of staff. Extensive prior research has adopted a quantitative approach, thereby failing to explore in detail the perspective of mental health nurses. The literature also neglects secure mental health settings

METHODS: The study aimed to explore the attitudes of mental health nurses toward service users who self-harm in secure environments, and to inform mental health curriculum development. It was conducted in a large forensic mental health unit, containing medium and low secure facilities, to the west of London, UK. A qualitative multi-method approach was adopted, underpinned by interpretative phenomenological analysis. Data were obtained from mental health nurses using individual interviews and focus groups, and analysis followed a step-by-step thematic approach using interpretative phenomenological analysis

RESULTS: Nurses' attitudes toward self-harm varied but were mainly negative, and this was usually related to limited knowledge and skills. The results of the study, framed by the Theory of Planned Behaviour, led to the development of a proposed educational model entitled 'Factors Affecting Self-Harming Behaviours' (FASH

CONCLUSION: The FASH Model may inform future curriculum innovation. Adopting a holistic approach to education of nurses about self-harm may assist in developing attitudes and skills to make care provision more effective in secure mental health settings

Keywords: Attitudes to self-harm; Mental health curriculum; Interpretative phenomenological analysis; Nurses; Secure environments

1. Introduction

This paper reports on a qualitative study into the attitudes of nurses toward users who self-harm within a large secure mental health unit in London. The study has been reported in full elsewhere with particular emphasis on practice implications (Sandy & Shaw, 2012), and the present purpose is to report on the educational implications of the results.

Self-harm is a significant international public health problem with increasing incidence (Sandy, 2013). In a document published by the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2009), it is indicated that globally between 10 and 100 million incidents of self-harming behaviour occur every year. Citing the United Kingdom (UK) as an example, the incidence of this behaviour has been rising since the 1960s (Mental Health Foundation, 2006). More recent studies report that self-harm is responsible for 24,000 hospital admissions in England each year (Long & Jenkins, 2010). Similar claims have been made by the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety in Northern Ireland (DHSSPS NI, 2008). It is estimated that self-harm is responsible for 7000 hospital admissions per year in the province of Northern Ireland, a rate that has increased by 9% since 2000. These figures are likely to be an underestimate because of the secrecy associated with the behaviour, and estimates of its incidence tend to vary between countries. For example, a review of the work of Favazza and Rosenthal (1993) and Walsh and Rosen (1988) in the United States of America by Sakinofsky (2000) unveiled a self-harm rate of 300-1400 people per 100, 000 of the general population. A review of the UK literature by Cooper et al. (2005) indicates that self-harm is responsible for 170, 000 admissions per year to UK hospitals. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) considers this rate the highest in Europe (NICE, 2004). As regards the Republic of South Africa (RSA), there are no reliable figures on the incidence of self-harm. There are a couple of published accounts based on retrospective record analysis. But, as Favara (2013) points out, many cases of physical (as opposed to chemical) self-harm are fatal, and other cases are turned away from busy critical care units. From the data that are available, however, it appears that self-harm is a significant problem in South Africa. In addition to the human cost, it has a substantial impact upon health care resources (Favara, 2013).

Whilst these studies indicate the historical nature of the behaviour of self-harm, the variation in rates illustrated is attributable to the absence of a universal definition which, in Magnall and Yurkovich (2008) view, is reflected in healthcare workers' use of a number of definitions and terms, such as deliberate self-harm and self-mutilation in describing self-harming behaviours. Such usage causes confusion for both researchers and healthcare workers. In this paper, the term self-harm is used to refer to all self-harming behaviours, which is in accordance with the NICE definition, "… self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of the apparent purpose of the act." (NICE, 2004, p. 7).

Self-harming behaviours are common among people with mental health problems, causing distress to the individuals concerned. This association was demonstrated, for example, in Lippi's study (2012) that established a strong correlation between self-harm and depression in South Africa. Self-harm also impacts on nurses, who are charged with safeguarding users, and it has resource implications. It is therefore a problem worthy of investigation.

The literature indicates a mis-match in motivational attributions for self-harm between nurses and users. This has the potential to negatively affect professional-user relationships, undermine care, and perpetuate self-harming behaviour. What follows is a summary of the relevant literature and theoretical stance, followed by an account of the methods used in the present study. From that point, the paper focusses on those findings that have educational implications.

Self-harm is a complex multidimensional behaviour, and such complexity indicates a multitude of reasons motivating people to engage in it. Tension release is one of the most commonly cited reasons by users, as they tend to report emotional release and subsequent feelings of calm following acts of self-harm (Sandy, 2013). Communication of unbearable feelings (such as anger), self-cleansing, driving others away, regaining control of their lives and coping with stigmatisation and labelling are motives also frequently expressed by users (Bosman & van Meijel, 2008). Punishing others and avoidance of the impulse to commit suicide are other reasons for self-harm, but these motives are unusual (Sandy, 2013). It is important to note that most of the research literature focusses on Western countries, yet it is well established that cultural factors play an important part in self-harm.

For many years, users who self-harm have been described as manipulative and attention-seeking (Cook, Clancy, & Sanderson, 2004). More recently, Sandy and Shaw (2012) assert that healthcare workers often perceive people who self-harm as time wasters and unworthy of treatment. These negative perceptions have the potential to impede therapeutic engagement, a view regularly reiterated in the literature (Wilstrand, Lindgren, Gilje, & Olofsson, 2007). Although these claims of negative attitudes should be treated with caution since there is limited evidence to support them, there are grounds for further investigating the nature and acquisition of attitudes since any educational intervention will depend on such an understanding.

It is clear that the existing research literature is biased towards quantitative studies (McCann, Clark, & McConnachie, 2007). Most of these studies focussed on exploring this behaviour in Accident and Emergency departments and generic psychiatric settings, neglecting to consider self-harm in secure mental health settings (Hadfield, Brown, & Pembroke, 2009). Previous studies do provide tantalising suggestions that self-harm among users might be perpetuated by the inappropriate behaviour of nurses, such as ignoring and ascribing negative labels, which can be harmful to the health of both themselves and users (Mchale & Felton, 2010). The next section relates to the theoretical basis considered in developing a model for those who educate mental health professionals.

2. Theoretical underpinning

The core concept is attitude, which is described by Rosenberg and Hovland (1960) as predispositions to respond to some class of stimulus with certain classes of response. In this case, the stimulus is self-harm and the health professional (nurse) provides the response. Drawing on the earlier work of Festinger (1957), she identify three elements of response: the affective element concerns the feelings of the individual and whether they evaluate the stimulus positively or negatively; the cognitive element is more objective and concerns the beliefs of the individual in relation to the stimulus; and the behavioural element is the individual's physical response to the stimulus. Gross (2010, p. 367) explains that attitudes provide us with "…ready-made reactions to and interpretations of events …". Here we can consider how a nurse habitually feels about, thinks about and behaves in response to an act of self-harm.

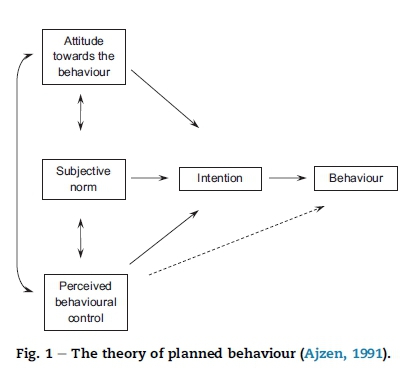

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is one of the most contemporary social cognition theories that seeks to inform the relationship between attitudes and behaviour. First forwarded by Ajzen in 1985, and having more distant roots in the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). This model has been widely applied in the explanation, prediction and influence of a range of health-related and other behaviours, including sex and exercise (Connor & Norman, 2005). Here, the TPB is considered in relation to the behaviour of nurses in response to self-harming acts by users.

A major strength of the TPB is that it seeks to explain and predict non-volitional as well as volitional behaviours. It thus acknowledges that behavioural performance is influenced by psychological and social factors that are perceived to influence one's ability to carry it out. In a later section, it will be seen that this is important when considering complex behaviours, such as responding to self-harm within a social setting.

As shown in Fig. 1, the TPB model posits that the most proximal determinant of behaviour is intention to act, which refers to the strength of motivation to try and change, adopt or stop a behaviour. However, this is influenced by three sets of factors. First, an individual's attitude towards the behaviour, which comprises the extent to which the behaviour is valued, and the extent to which the individual believes that the behaviour will lead to the desired outcome. Second, subjective norm refers to the perceived expectations of others in relation to a particular behaviour, along with perceived social pressures. Finally, perceived behavioural control refers to the individual's perception of facilitators and barriers, including efficacy expectations. Relationships between these elements are shown in Fig. 1 by the use of arrows. Here the TPB is used to explain the findings of the study, and is later linked with recommendations for educational action.

2.1. Rationale

In view of the limitations of the existing literature, this study was intended to contribute to the literature by adopting a qualitative approach to investigating nurses' attitudes toward self-harm in the context of secure mental health settings in order to generate recommendations for training and education.

3. Methods

3.1. Aim

The aim of this study was to report the attitudes of nurses toward user who self-harm in secure environments, and propose educational recommendations derived from such results.

3.2. Design

The study adopted a qualitative approach using a multi-method design. The design was phenomenology, specifically interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (Smith, 2005). This strand of phenomenology requires the researcher to go beyond the description of phenomena, reporting not just what participants verbalise about their experience, but also offering expert analysis of these experiences.

3.3. The setting

The study setting was a large forensic mental health unit to the west of London. The unit comprises a mixture of medium and low secure facilities. The medium secure facilities serve a regional catchment area in southern England and therefore accept users with a broad range of socio-demographic backgrounds, often coming from troubled families and communities. Nurses employed within the unit varied too as they hailed from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds. One of the primary criteria for admission to these facilities is violence. Users with a high risk of violence are generally admitted to the acute wards. These users might progress through the wards from higher to lower secure facilities, as their risk of violence decreases. A range of mental health workers contribute to the care of these users, but because of their continuous close contact, nurses have by far the greatest opportunity to influence the management of self-harm.

3.4. Sampling and recruitment

The Trust comprised 15 secure clinical areas with an average of 22 registered nurses working in each area. This staff group constituted the population of interest. Eligibility for recruitment was based upon having at least two years' experience of working with self-harm within this type of clinical environments.

Following ethical clearance, potential participants were approached in the following way. First, one of the authors met with each clinical team in order to explain the study, and to answer queries. Each member of the team was given an information sheet and a letter of invitation. The information sheet contained the researcher's contact details, and nurses who were prepared to participate were asked to make contact. As a result of this, 80 nurses made contact with the researcher, and thus formed a volunteer sample pool from which individuals were purposively selected.

3.5. Data collection methods

Data collection was preceded by piloting, after which recruitment commenced and continued until category saturation was achieved. This was the point at which no new relevant data to address the aims and objectives were revealed. This culminated in 25 individual interviews and six focus group interviews, each of which comprised six participants (N = 61). Individual interviews formed the first wave of data collection, followed by the focus groups in order to ensure clarification and in-depth discussion of issues not fully addressed in the individual interviews. There was an even representation of females and males, and the mean age was 29 years (range = 56-25 years). Approximately 50% of the sample was of African-Caribbean descent, and the other 50% comprised a mixture of European and other decent. On average, nurses had 3 years experience in working with self-harm, and limited or no training in this behaviour. All interviews were audio-recorded, and proceeded according to a semi-structured schedule (see Table 1). Focus groups followed standard guidelines and were conducted by one of the authors and a research assistant.

3.6. Data analysis

Data were collected in interviews over a period of a year from 2010 to 2011. Data collection and analysis were conducted in parallel in order that the selection of participants could be guided by the data already yielded. Data were fully transcribed and then subjected to analysis using IPA (Langdridge, 2007). The two authors conducted blind reliability checks in order to ensure confirmability.

3.7. Ethics

Ethical threats were encountered at the design stage and the study conforms to The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Permission to undertake this study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Services and the research site Ethics Committee. The main ethical threats were in the areas of consent, confidentiality and anonymity. Written informed consent was obtained and participants were free to withdraw at any time. All data were stored securely in accordance with the privacy and data collection laws. As regards anonymity, at the point of transcription names were substituted for code numbers, and in all reports, great care was taken to change any information by which a participant or clinical area could be identified. A debriefing, and detailed member checking immediately followed individual and group interviews. On completion of the study, verbal presentations and copies of the summary report were offered to the clinical areas involved. The study received no external funding.

4. Results

Table 2 shows that the data yielded one super-ordinate theme (attitudes to self-harm), two second order themes (negative and positive attitudes) and a number of sub-themes indicated in bold italics. Extracts from participants' narratives are used to support the discussions of identified themes. The initials 'In' and 'Fg' identify data from individual interviews and focus group interviews respectively.

As Table 2 shows, participants expressed mixed attitudes toward self-harm, both negative and positive, but mainly negative ones. In relation to negative attitudes, most participants were of the opinion that some users would continue to hurt themselves irrespective of interventions. This indicates that the educational deficit is not just in the areas of knowledge and skills, but attitudes too. Negative attitudes were frequently associated with feelings of anger and frustration. These emotions were particularly associated with those who repeatedly self-harm, and labels, such as 'timewasters' and 'attention seekers' were frequently used by participants to describe users.

Some nurses don't bother whether they hurt themselves. They often call them names: attention seekers and timewasters (Fg).

According to a few participants, such responses are unhelpful as they serve to make users only feel worse about themselves. They stressed that feeling this way may perpetuate the need for self-harm and discourage users from seeking help.

My colleagues and I believe that negative attitudes toward users and their behaviour can drive them away from us (In).

Reluctance to seek help was a huge concern for some participants. They added that the users find the ascription of negative labels dehumanising and insulting.

Users find the labels we ascribe on them insulting, and so often repeat their behaviours (In).

Most participants believed that ascribing labels is indicative of nurses' misunderstanding of the motives of users' self-harming behaviour.

It is our thoughts of them as attention seekers and unworthy of care that tend to make us misunderstand them. They self-harm to cope with distress (Fg).

Participant stressed that the labels ascribed serve as a deterrent for developing a better understanding of users. Being rigid and controlling are other examples of negative attitudes cited by most participants. According to participants, this could involve telling users what to do and restricting their movements. This manner of responding to users could result in more self-harming behaviours and, thus, participants advised nurses to use rigid and controlling approaches with caution.

They hate any form of restriction on their freedom. It frustrates and causes them to self-harm more. So, we must be mindful not to overdo it (In).

Some participants reported that users are sometimes shouted at in clinical practice. They further stated that users do not like to be locked up and shouted at.

Shouting at them is disrespectful. It drives them away from us and makes them self-harm more (In).

Whilst some participants agreed that being rigid and controlling is effective in the short term to reduce self-harm rates, they were unaware of their long-term effects on perpetuating self-harming behaviours. This is an indication of a deficit in knowledge of self-harm and the risk of providing sub-standard care. Yet most of the participants reported not to have had training in this area of practice. However, some of these participants refused to undertake training when offered to them stating that they were aware of how to care for people who self-harm.

Trainers can't tell me anything new about self-harm. I know what to do when people hurt themselves (Fg).

The refusal of some participants to undertake training in self-harm was a function of their experiences of caring for users who present with this behaviour.

Some of us have over five years' experience of caring for users who self-harm. We know what to do to prevent and care for them (Fg).

Some participants claimed that care provision to users with self-harming behaviour is different from that of other user groups. They stressed that a blanket approach is often used to respond to the needs of users who self-harm.

Some nurses treat users who self-harm the same. They are always put them on observation and do not listen to them. Other users are listened to (In).

Individualising care provision was considered important by some participants because it creates an opportunity for users to be provided with the care they need.

I find the adoption of a blanket approach for users who self-harm tormenting. It ignores their individual needs, and impact on the development of therapeutic relationships (Fg).

Whilst some participants advocated individualised care, others talked about insensitive responses of nurses to users' self-harming behaviours.

I have overheard a colleague saying if you want to cut yourself do it when I am not around (In).

Some participants stressed that insensitive responses indicate disregard for users' feelings of distress. They added that not showing willingness in trying to understand how users feel could result in more self-harming acts.

With regard to positive attitudes, the need for training in self-harm was frequently mentioned by participants in both individual and focus group interviews more than any other sub-theme. Most nurses felt inadequately prepared to care for users who self-harm. They admitted that this knowledge deficit sometimes resulted in sub-optimal care provision. The data were clear that the difficulties nurses sometimes experience when dealing with self-harm are at least partly the result of lack of training in self-harm. Some participants therefore welcome training in this area of practice.

Not knowing what to do is a stumbling block. This is a problem for most of us, if not all, in this unit (Fg).

Another participant further articulated the need for training for nurses caring for users who self-harm.

Caring for people who self-harm can be emotionally upsetting. I initially found it stressful because of lack of understanding of the reasons behind their behaviours. After training, it became much easier to engage with them (In).

Increased understanding of self-harm, including, for example, why users hurt themselves, was also seen by some participants to promote quality care. They claimed that such understanding could result in reduced negativity towards individuals who harm themselves.

We used to refer to them as attention seekers. But understanding the reasons for their behaviours has enabled us to accept and support them (In).

Some participants believed that demonstration of unconditional acceptance of users and listening to their narratives are critical approaches that indicate respect and readiness to offer help. Adoption of such approaches, participants stressed, would result in better professional-user partnerships.

Irrespective of the reasons for self-harm, we must remain non-judgemental and listen to them. Listening to their stories would help us develop a better working relationship with them (Fg).

Some participants claimed that working in partnership with users who self-harm can be a difficult task to achieve, particularly in instances where the behaviours are frequently repeated. They attributed this difficulty to the range of negative emotions, such as anger and frustration that self-harm evokes. Participants therefore advocate for nurses to be given adequate support, for example, through training and education to cope with these emotions.

Users sometimes make you feel angry and frustrated particularly when they keep on repeating their behaviours. But training can help us to cope with these emotions (In).

Feelings of optimism that users can be enabled to adopt alternative means other than self-harm to express their emotions, was pervasive among some participants. They claimed that being optimistic enhances users' motivation to stop or reduce the frequency of their self-harming behaviour.

I think being hopeful that users can stop harming themselves one day is the most important thing (Fg).

The participants of this focus group clarified what the phrase ' the most important thing' means.

The users in this unit have lost hope. But if we are hopeful the users will develop hope and stop harming (Fg).

Most participants were of the opinion that people who self-harm usually experience feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. They reiterated that the role of nurses is to alleviate these feelings and instil hope in this user group. Commitment to offer help and provision of choice of activities were identified as strategies for instilling hope and reducing self-harming behaviours. Participants therefore called for the inclusion of these strategies in all training programmes of self-harm.

I realised over the years that users liked to be involved in their treatment and to be provided with choice of activities (Fg).

5. Discussion

In this study, many participants admitted to a deficit in knowledge, skills and positive attitudes in respect of self-harm, and perhaps their professional education did not adequately prepare them to practise with confidence in addressing self-harm problems. The literature contains abundant evidence that these shortcomings are also evident to users, who often perceive negative attitudes among nurses (Tantam & Huband, 2009). Participants often stated that more specific education would enable them to respond with more confidence and in a positive manner, facilitating the development of therapeutic relationships. This view is supported by the literature since educational interventions have demonstrated a positive effect on professionals' attitudes toward self-harming individuals. For example, Gough and Hawkins (2000) report enhanced optimism, confidence, enthusiasm and positive feelings among healthcare professionals following an educational intervention.

So the question is what sort of educational intervention would be appropriate. Here we might consider two areas: curriculum structure and curriculum process. As regards curriculum structure, the TPB provided an understandable framework in which the data could be explained and, following data analysis, led the authors proposing a more specific model to plan curricular content so nurses would be adequately trained in dealing with users who self-harm. From this, a theoretical framework called the FASH (Factors Influencing Attitudes Toward Self-Harm) Model was developed and is proffered here as a basis for curriculum planning. It will be recalled (see Fig. 1) that the TPB contains four main elements: attitudes toward the behaviour, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and intentions. Fig. 2 shows that the FASH model accommodates all these elements, which need to be present in the self-harm curriculum, and provides important pointers for educational practice.

Positive attitudes toward the behaviour can be influenced by emphasising the link between the behaviour (responding positively to self-harm) and favourable outcomes (decreased repetition of self-harm), supported by appropriate evidence. Additionally, teaching methods (e.g. discussion group and role play) that are appropriate to attitude change and the development of professional values need to be used.

As regards subjective norms, this relates to the perceived expectations of others and perceived social pressures, i.e. the values that practitioners are expected to follow and which define behaving in a professional way. In mental health settings, care provision is strongly influenced by a range of policies, legal frameworks and clinical guidelines. These perceived norms could also be informal and unofficial, i.e. colleagues' attitudes and behaviour toward self-harm. Prolonged exposure to both formal and informal influences in a secure environment will help to shape attitudes. The curriculum therefore needs to extend into clinical areas and involve managers, supervisors and mentors.

The third component of the TPB is perceived behavioural control. This means that if an individual has self-belief and confidence that they are able to perform a given behaviour, they are more likely to do so (Ajzen, 1991). As Fig. 2 shows, therefore, the curriculum must find room for the exploration of barriers and the enhancement of self-efficacy. The present study indicates that, with the right support, prolonged exposure to clinical encounters with self-harming users can lead to increased confidence and skill levels. This appears to be partly a function of age.

As Fig. 1 shows, behavioural intentions are the most proximal determinant of enacted behaviour. However, intentions are not a perfect predictor of behaviour change. Studies in health psychology have shown that encouraging people to formulate an action plan, including the identification of potential barriers and ways of overcoming them, enhance interventions aimed at achieving health behaviour change (Sniehotta, Scholz, & Schwarzer, 2005). Here it is suggested that educational interventions should also aim to bridge this intention-behaviour gap by including classroom activities that require students to write down areas needing changes and state how they plan to put their suggestions into practice.

As regards curriculum process, teaching methods that go beyond information-giving and engage the whole person have long been associated with attitude change. For example, this is advocated in the adult learning literature (Knowles, 1990) and the humanistic literature, for example in the work of Carl Rogers. Such teaching methods should address all three components of attitudes, i.e. beliefs, emotions and behaviour (Festinger, 1957). Teaching methods, such as role play and feedback are likely to be effective.

Classroom activities that link anticipated critical situations around self-harm to goal-directed responses are more likely to result in raised self-efficacy and desired responses automatically occurring in clinical practice. In order to achieve this, facilitators may consider methods, such as case study analysis and practical simulation exercises. It is hoped that by engaging the whole person in learning activities, nurses will learn to distinguish between demonstrating positive unconditional regard for the individual user, and the need to address unwanted self-harming behaviour.

Nurses are more likely to value a behaviour if they are persuaded of the link to practice, and if the source of the information is credible. Therefore, in line with the TPB (subjective norms) clinicians who have positive attitudes to self-harm and can act as credible role models should be involved in curriculum delivery in the classroom as well as in practice.

It is possible that some nurses with negative attitudes may, for a variety of reasons, resist formal educational intervention. This can of course be addressed through the appraisal and clinical supervision structures, but influence can also be applied by means of the therapeutic milieu through multi-disciplinary meetings, educational activities and the support of good role models.

6. Conclusion

Participants reported more negative than positive attitudes toward self-harm. The majority of participants expressed a need for training in caring for users who self-harm. The FASH and TPB were explained, and they serve as promising frameworks to guide curricular development for addressing nurses' training needs.

The main limitation of this study is that, by design, it focussed on nurses' attitudes and did not attempt to obtain users' views of self-harm. Clearly, there is a need for future researchers to give this group a voice. This was a qualitative study involving a non-probability sample in a UK secure forensic mental health unit. So the results cannot be generalised to other population groups. Besides, for qualitative research the concept of transferability is preferred to generalisability. This means that the reader should judge the applicability of the findings to their own situation. Details given in the method and result sections should enable this judgement to be made.

Notwithstanding these limitations, three outcomes of this study are of educational significance and may further contribute to the advancement of practice. First, researchers might usefully consider applying the same methodology to other mental health populations in different localities and different parts of the world. Although there are useful pointers here, studies should also be conducted in African settings. And, although the main burden of managing self-harm falls on nurses, it would also be useful to learn of the attitudes of other health workers, such as psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists. Second, the research provides a basis for policy development in respect of self-harm risk assessment, risk management, planning and clinical audit tools. Third, the FASH model may serve as a useful framework for curriculum planning at both under-graduate and post-graduate levels.

The main strength of this study is that by using a multi-method qualitative approach to examine a neglected area of practice, it has helped fill a real gap in the literature. It is the first study to have done this. The study has added to the growing body of evidence that many nurses hold negative attitudes toward self-harm. In order to modify these attitudes, future studies should apply a holistic educational intervention and evaluate both process and outcome (clinical impact). The FASH model was designed to provide a theoretical framework to help curriculum planners address this practical problem. In this way, it is hoped that this study will provide professional guidance for those who are responsible for safeguarding this vulnerable group of adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the nurses of the study site who offered their knowledge and experiences of self-harm.

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Kuhl, & J. Beckman (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behaviour (pp. 11e39). Heidelberg: Springer. [ Links ]

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179e211. [ Links ]

Bosman, M., & van Meijel, B. (2008). Perspectives of mental health professionals and patients on self-injury in psychiatry: A literature review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 22, 180e189. [ Links ]

Connor, M., & Norman, P. (2005). Predicting health behaviour. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Cook, S., Clancy, C., & Sanderson, S. (2004). Self-harmand suicide: Care, interventions and policy. Nursing Standard, 18(43), 43e52. [ Links ]

Cooper, J., Kapur, N., Webb, R., Lawlor, M., Guthrie, E., Mackway, K., et al. (2005). Suicide after deliberate self-harm: A four year cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 297e302. [ Links ]

DHSSPS(NI). (2008). Draft suicide prevention strategy to protect life: A shared vision. Belfast: Department of Health, Social Services and Prison Services (Northern Ireland). [ Links ]

Favara, D. M. (2013). The burden of deliberate self-harm on the critical care unit of a peri-urban referral hospital in the Eastern Cape: A 5-year review of 419 patients. South African Medical Journal, 103(1), 40e43. [ Links ]

Favazza, A. R., & Rosenthal, R. J. (1993). Diagnostic issues in selfmutilation. Hospital Community Psychiatry, 44(2), 134e140. [ Links ]

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of cognitive dissonance. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Gough, K., & Hawkins, A. (2000). Staff attitudes to self-harm and its management in a forensic psychiatric service. British Journal of Forensic Nursing, 2(4), 22e28. [ Links ]

Gross, R. (2010). Psychology: The science of mind and behaviour. Abingdon: Hodder. [ Links ]

Hadfield, J., Brown, D., & Pembroke, L. (2009). Analysis of accident and emergency doctors' response to treating people who selfharm. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 755e765. [ Links ]

Knowles, M. (1990). The adult learner: A neglected species. Gulf, Houston Texas. [ Links ]

Langdridge, D. (2007). Phenomenological psychology: Theory, research and method. Harlow: Pearson. [ Links ]

Lippi, C. (2012). An exploratory study of the correlation between deliberate self-harm and symptoms of depression and anxiety among a South African university population. Unpublished MA Dissertation. University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Long, M., & Jenkins, M. (2010). Counsellors' perspectives on selfharm and the role of the therapeutic relationship for working with clients who self-harm. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 10(3), 192e200. [ Links ]

Magnall, J., & Yurkovich, E. (2008). A literature review of deliberate self-harm. Perspective of Psychiatric Care, 44(3), 173e184. [ Links ]

McCann, T. V., Clark, E., & McConnachie, S. (2007). Deliberate selfharm: Emergency department nurses' attitudes, triage and care intentions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16, 1704e1711. [ Links ]

Mchale, J., & Felton, A. (2010). Self-harm: What's is the problem? A literature review of the factors affecting attitudes towards self-harm. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing, 17, 732e740. [ Links ]

Mental Health Foundation. (2006). Truth hurt: Report of the national inquiry into self-harm among young people. London: Mental Health Foundation. [ Links ]

NICE. (2004). The short term physical and psychological management and prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. In National clinical guidelines 16. London: NICE. [ Links ]

Rosenberg, M. J., & Hovland, C. I. (1960). Cognitive, affective and behavioural components of attitude. In In, M. J. Rosenberg, C. I. Hovland, W. J. McGuire, R. P. Abelson, & J.W. Brehm (Eds.), Attitude, organisation and change: An analysis of consistency among attitude components. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Sakinofsky, I. (2000). Repetition of suicidal behaviour. In K. Hawton, & K. Van Heeringen (Eds.), The International handbook of suicide and attempted suicide (pp. 385e404). Chichester: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Sandy, P. T. (2013). Motives for self-harm: Views of nurses in a secure unit. Journal of International Nursing Review, 60(3), 358e365. [ Links ]

Sandy, P. T., & Shaw, D. G. (2012). Attitudes of mental health nurses to self-harm in secure forensic settings: A multimethod phenomenological investigation. Journal of Medicine and Medical Science Research, 1(4), 63e75. [ Links ]

Smith, J. A. (2005). Semi-structured interviewing and qualitative analysis. In J. A. Smith, R. Harre, & L. van Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking methods in psychology (pp. 9e26). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Bridging the intention-behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology and Health, 20(2), 143e160. [ Links ]

Tantam, D., & Huband, H. (2009). Understanding repeated self-injury: A multidisciplinary approach. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Walsh, B. W., & Rosen, P. M. (1988). Self-mutilation: Theory, research and treatment. London: Guildford Press. [ Links ]

WHO. (2009). Suicide prevention strategy. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [ Links ]

Wilstrand, C., Lindgren, B. M., Gilje, F., & Olofsson, B. (2007). Being burdened and balancing boundaries: A qualitative study of nurses' experiences caring for patients who self-harm. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14, 72e78. [ Links ]

Received 11 April 2015

Accepted 2 August 2016

Available online 2 October 2016

Peer review under responsibility of Johannesburg University.

E-mail addresses: david.shaw@bucks.ac.uk (D.G. Shaw), sandypt@unisa.ac.za (P.T. Sandy).

* Corresponding author. Fax: +27 12 429 3361.