Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.21 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.05.002

FULL LENGTH ARTICLES

Perceptions of patient-centred care at public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay

Sihaam Jardien-BabooI, *; Dalena van RooyenII; Esmeralda RicksI; Portia JordanI

IDepartment of Nursing Science, School of Clinical Care Sciences, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, South Africa

IISchool of Clinical Care Sciences, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In South Africa, the quality of health care is directly related to the concept of patient-centred care and the enactment of the Batho Pele Principles and the Patients' Rights Charter. Reports in the media indicate that public hospitals in the Eastern Cape Province are on the brink of collapse, with many patients being treated in condemned hospitals which lacked piped water, electricity and essential medical equipment. Receiving quality care, and principally patient-centred care, in the face of such challenges is unlikely and consequently leads to the following question: "Are patients receiving patient-centred care in public hospitals?"

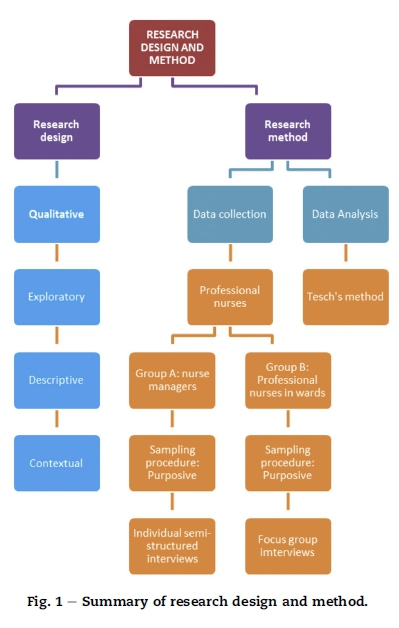

A qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual study was conducted to explore and describe the perceptions of professional nurses regarding patient-centred care in public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a total of 40 purposively selected professional nurses working in public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay, Eastern Cape Province. Interviews were analysed according to the method described by Tesch in Creswell (2009:192).

Professional nurses perceive patient-centred care as an awareness of the importance of the patient's culture, involving the patient's family, incorporating values of love and respect, optimal communication in all facets of patient care and accountability to the patient. Factors which enable patient-centred care were a positive work environment for staff, nursing manager's demonstrating exemplary professional leadership, continuous in-service education for staff and collaborative teamwork within the interdisciplinary team. Barriers to patient-centred care were a lack of adequate resources, increased administrative work due to fear of litigation and unprofessional behaviour of nursing staff.

Although the professional nurses had clear perceptions of patient centred care, there are barriers to rendering patient-centred care under the prevailing conditions, which posed a challenge.

Keywords: Patient-centred care;Professional nurse; Public hospital

1. Introduction

The need for patient-centredness has become an important global issue, having been identified by the Institute of Medicine of the United States National Academies of Science as one of six attributes of quality health care (World Health Organisation, 2007:5). The essence of patient-centred care is an attempt at understanding the experience of illness from the patient's perspective. The International Alliance of Patients' Organisations' (IAPO) Declaration on Patient-Centred Health Care states that "the essence of patient-centred health care is that patients are at the centre of the health care system and therefore the system is designed around them" and "the required outcome of health care is a better quality of health, and/or of life, as defined by the patient (IAPO, 2007:12). The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2010:5) supports the IAPO's description of patient-centred care, stating that understanding patient-centred health care will lead to improved health outcomes as health care is provided in a way that better meets the needs of patients.

In the South African context, the concept of patient-centred care is endorsed in the Constitution of South Africa Second Amendment Act, no. 3 of 2003 (South Africa, 2003) in which it is stated that all citizens have the right to health care that is caring, free from harm and as effective as possible. In addition to this, the White Paper on Transforming Public Service Delivery (Batho Pele White Paper no. 1459 of 1997) was published by the Department of Public Service and Administration (South Africa, 1997). "Batho Pele", roughly translated from the Sotho language, means "people first". The eight Batho Pele principles seek to introduce a new approach to service delivery that puts people first, and encapsulates the stated values of public service in South Africa, which directly relate to the concept of patient-centred care. Briefly these principles state that citizens should be consulted about the level and quality of the public services they receive and, wherever possible, be given a choice about the services that are offered; be told what level and quality of public services they will receive so that they are aware of what to expect; have equal access to the services to which they are entitled; be treated with courtesy and consideration; be given full, accurate information about the public services they are entitled to receive; be told how national and provincial departments are run, how much they cost, and who is in charge. If the promised standard of service is not delivered, citizens should be offered an apology, a full explanation and a speedy and effective remedy, and when complaints are made, receive a sympathetic, positive response. Finally, public services should be provided economically and efficiently in order to give citizens the best possible value for money.

Bearing in mind the reference to patient-centred care in the aforementioned documents, this study focussed on a critical aspect of quality health care, namely the provision of patient-centred care as perceived by professional nurses working in public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay.

1.1. Problem statement

In South Africa the public health sector delivers services to about 80% of the population, but institutions in the public sector have suffered poor management, underfunding and deteriorating infrastructure, which have negatively impacted the rendering of patient-centred care (Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 2010: 797). As a result, a dichotomy exists between what is stipulated in the Batho Pele principles and the lack of effective service delivery in the public health sectors (Sebugwawo, 2012: 7).

Consequently, reports in the media indicate that the hospitals in the Eastern Cape, one of the nine provinces in South Africa, are on the brink of collapse with thousands of patients being treated in condemned hospitals where 168 clinics and 17 hospitals lacked piped water; more than 42 health facilities did not have electricity and operated via generators; 68% of hospitals did not have essential medical equipment, and the Provincial Health Department had a staff vacancy rate of 46% (Williams, 2012: 1). A report titled "Death and Dying in the Eastern Cape" released in September 2013 by the Eastern Cape Health Crisis Action Coalition [ECHCAC] (2013), was the result of an investigation into the breakdown of the public health care system in the province, which was described as collapsing. The results showed that many of the state hospitals are in a state of crisis (Eastern Cape Health Crisis Coalition, 2013), with much of the public health care infrastructure in poor condition and non-operational as a result of underfunding, mismanagement, and neglect. In a more recent report by Mayosi and Benatar (2014: 1345), the authors stated that the national public health sector remains the sole provider of health care for more than 40 million people who are uninsured and who constitute approximately 84% of the national population. Hence the majority of South Africans are utilising public health care, fraught with all the challenges alluded to.

Receiving and rendering quality care and indeed patient-centred care in the face of such challenges, lead to the following question: "Are patients receiving patient-centred care in public hospitals?" The researcher contended that the nurse's role is pivotal in delivering patient-centred care and therefore gauging their understanding of rendering patient-centred care in the context of a public hospital is imperative.

1.2. Aim

The aim of this study was to explore and describe professional nurses' perceptions of patient-centred care in public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay.

2. Research design and method

This study utilised a qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual research design to explore and describe the perceptions of professional nurses regarding patient-centred care in public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay. A summary of the research design and method for this study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

2.1. Research population

The research population of this study was professional nurses who were employed in public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay. Nelson Mandela Bay is one of six metropolitan areas in South Africa and includes the cities of Port Elizabeth, Uitenhage and Despatch and has a total of eight public hospitals; comprising two regional hospitals, two tertiary hospitals and four specialised hospitals. Four hospitals comprising two regional and two tertiary hospitals were purposively selected to be included in the research study, as they were the largest and offered the most comprehensive services. Since the majority of South Africans utilise public health care services, the issue of rendering patient-centred care within these public institutions form the focus of this study.

2.2. Sampling

Purposive sampling was used to select the participants in the study. Two groups (A and B) of professional nurses were sampled. Group A comprised of nurse managers and Group B comprised of professional nurses. The participants in Group A were diverse in terms of years of experience as a nurse manager in a public hospital, and the participants in Group B were diverse in terms of the units in which they had worked in the public hospitals. All participants all had to be professional nurses who are permanently employed and working in a public hospital for more than one year. Nurse managers had to have a minimum of 5 years' experience in a managerial position.

Group A: A nurse manager from each of the four hospitals was interviewed. The four managers were purposively selected because they were involved in the overall management of staff and patient care.

Group B: This group included 36 professional nurses, who they were directly involved with patient care as well as responsible for direct supervision and management of other categories of nurses.

2.3. Data collection methods

A triangulation method for data collection was used which included semi-structured individual interviews, focus group interviews, observations and field notes. Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with four nurse managers while four focus groups were conducted with 36 professional nurses. Focus group 1 consisted of 11 participants, focus group 2 consisted of 9 participants, focus group 3 consisted of 8 and focus group 4 consisted of 8 participants. A total of 40 participants were interviewed. A central question was asked to all:

"What are your perceptions of patient-centred care?" Freedom was given to participants to enable their experiences to be fully explored. Permission was requested from the participants to use a digital recorder in order to record the interviews which were transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data analysis

Tesch's method of identifying themes in the data was analysed, which allows a structured organisation of data to take place (Creswell, 2009:192). The analysis process included reading the transcriptions, writing thoughts, listing, clustering, coding and categorising the topics and, if necessary, recode data. Coding was undertaken by the researcher and also by an independent coder to ensure trustworthiness. During coding, themes which were repeated throughout the data collection were identified. These themes were used to provide the story told by the participants and to form the basis of any recommendations which might be made. To assist in the interpretation and validity of the findings, an analysis of the literature on the subject took place, together with data analysis (Streubert & Carpenter, 2011:158).

2.5. Pilot interview

The researcher conducted one semi-structured interview with a nurse manager and one focus group consisting of twelve professional nurses to assess the sampling procedure, research questions, interview technique, system for recording data and the data analysis method. No problems were encountered during the pilot interviews. The information obtained from these interviews was thus included in the data analysis as the research questions in the interview schedule did not need to be modified.

3. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University's Faculty of Health Science's Research, Technology and Innovation Committee (reference number, H12-HEA-NUR-011). Approval was received from the Eastern Cape Department of Health, the Port Elizabeth Hospital Complex management and the participants. The following ethical issues were applied throughout the study with the aim of protecting the participants: respect for human dignity, beneficence and justice (Polit & Beck, 2012:152).

4. Trustworthiness

Lincoln & Guba's (in Polit & Beck, 2012:584) principles of trustworthiness were adhered to throughout the study: credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability.

Credibility was ascertained by the thorough interviewing process, peer review of the research study by colleagues, reflexivity and triangulation. Dependability of the research findings was obtained by ensuring the credibility of the findings (Polit & Beck, 2012: 449). The audit trail enhanced the level of dependability of the study. The rich dense descriptions obtained by use of the transcribed interviews, the field notes of the researcher and the results of the focus group session were used to prove the dependability of the findings. Coding was carried out by an independent coder. The confirmability of the research findings was ensured by the provision of rich thick data obtained from the semi-structured interviews, the field notes of the researcher, and the transcript of the focus group session of professional nurses. Transferability was achieved by purposive sampling of professional nurses who were working in the public hospitals (Babbie, 2014:277) and through dense description of the research results, supported with verbatim quotations from the participants (Polit & Beck, 2012:585).

5. Results and discussion

The results of the data analysis yielded three themes, as illustrated in Table 1. Together with data analysis, a literature review on the subject took place to validate the qualitative findings (Streubert & Carpenter, 2011:158). The results and the discussion thereof are therefore merged, with relevant quotations and substantiating literature discussions.

5.1. Encompassing holistic care

Participants were enthusiastic about sharing their perceptions regarding what patient-centred care is and what it encompasses. Their perception that the patient should be seen as a human being with various components such as psychological, physical, social, emotional and spiritual aspects which impact on an individual's health was evident.

5.1.1. Awareness of the patient's culture

Participants observed that having knowledge of the culture of the patient and by implication, how to nurse a patient by taking the patient's culture into consideration, is akin to rendering patient-centred care. Owing to health care users from a diverse spectrum of cultures using the public health care system, professional nurses are exposed to treating patients with different languages, different values and different beliefs about health and disease management as indicated by the following quotation:

'Know the cultural differences. Because we differ. We have different cultural backgrounds. There are Whites, Blacks, and Coloureds (Focus group 3, page 18)'.

In order to render patient-centred care, the nurse therefore has to demonstrate cultural awareness which, according to Matteliano and Street (2012: 426), is "the ability to understand one's own culture and perspective alongside the stereotypes and misconceptions associated with other unknown or less known cultures and statuses and are a first step toward providing culturally competent care". Culture is multifaceted and it is therefore imperative for nurses and all health care professionals to try to understand the culture of the patient in order to render effective care. Van Rooyen, Jordan, Brooker, and Waugh (2009: 158) point out that nurses have to be sensitive to the cultural expectations of individual health care users and families, without making stereotypical assumptions, if they are to deliver holistic care. In this regard Chenoweth, Jeon, Goff, and Burke (2006: 34) state that "the development of a nursing workforce that is equipped with knowledge and an embedded attitude of cultural sensitivity and safety is a nursing workforce that will bring about positive change and improved consumer experiences." Similarly, Madeleine Leininger's Trans-cultural nursing model challenges nurses to become trans-cultural practitioners in order to more appropriately meet the needs of people from different cultures when they are seeking or needing nursing care (Blackman, 2011:32).

5.1.2. Patient's family involvement

Participants felt that families should be involved in the care of the patient as part of rendering patient-centred care as supported by the following statement:

'Also I think we must also try and involve family more with the relatives who are lying here. Sometimes you try to push the family aside. So what I'm trying to say is that if we can just get the family involved while the patient is still in hospital (Focus group 4, page 30)'.

The involvement of the family is an important component of patient-centred care, and this was evident in this research study in which similarities and differences across the varying definitions and descriptions of patient-centred care were identified. In a systematic review of nine models and frameworks for defining patient-centred care, the involvement of family and friends appeared in five of the definitions, indicating the significance of family involvement in rendering patient-centred care (Shaller, 2007:4). According to Mitchell, Chaboyer, Burmeister, and Foster (2009: 544) families are the single greatest social institution that influences a person's health. Therefore involving family is an enabler of patient-centred care.

5.1.3. Values of love and respect

Participants perceived treating patients with love and respect was as rendering patient-centred care. One participant illustrated this as follows:

'I think when one nurses the patient, one has got to be able to treat them with love and respect and dignity and without being prejudice' (Focus group 1, page 1).

Another component of rendering holistic, patient-centred care is incorporating the values of love and respect when interacting with the patient and family members. Fitzgerald and van Hooft (in Dowling, 2004: 1289) suggest that nurses understand love in nursing as "going beyond" the traditional duty of care, and the willingness and commitment "to want the good of the other before the self". In a study by Kvale and Bondevik (2008: 586), findings indicated that to be treated with respect as adults included being listened to and believed and this resulted in patients feeling valued, increased their self-worth and gave them a sense of control. The participants spoke about displaying values of respect, love and dignity when interacting with the patients, and perceived these values to be integral to patient-centred care (Kvale & Bondevik, 2008: 586).

5.1.4. Optimal communication

Participants felt that nurses should be aware of their verbal and non-verbal communication, and elaborated on methods of communication which should be adopted when communicating with patients, which will facilitate patient-centred care. More specifically, participants stated that gestures such as smiling and the manner in which a patient is addressed enabled patient-centred care. The tone which the nurse uses should be respectful and not loud, as indicated by the verbatim quotations:

'I think you must be friendly. A friendly face really relaxes the patient. Smile. And your attitude towards the patient is very important. When you talk, talk in a soft tone, not shouting, screaming at the patient. Body language is also important. Sometimes you say something, but the eyes and the body say something else. Smile, touching the patient' (Focus group 1, page 1).

According to Levinson, Lesser and Epstein (2010: 1311) communication skills are a fundamental component of patient-centred care. Evidence (Arora, 2003:791-806; Epstein & Street, 2007:89) demonstrates that patient-centred communication has a positive impact on important outcomes, including patient satisfaction, adherence to recommended treatment, and self-management of chronic disease. Robinson, Callister, Berry, and Dearing (2008: 602) note that effective communication between health care professionals is related to effective patient-centred care practices.

5.1.5. Nurse accountability

Participants felt strongly that the nurse should be accountable for his/her actions. An example of accountability by a participant was evident when she related that a patient who was diagnosed with cancer had to receive chemotherapy, but was not aware about the diagnosis or the treatment. The professional nurse took it upon herself to educate and explain to the patient about the chemotherapy, the effects and side-effect, as related in the quotation:

'Just to add, I think it also goes with accountability on my side as a nurse. You'll find out that the patient has been diagnosed with cancer, but until the patient has to get chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, the patient does not know that she has got cancer. So for me as a sister who is going to give chemotherapy, I won't say that Doctor was supposed to tell you, I account myself to this that I counsel the patient. I explain what is happening' (Focus group 3, page 22).

In a qualitative study by Luxford, Safran, and Delbanco (2011: 513) of facilitators and barriers in health care organisations with a reputation for improving the patient experience, interviewees mentioned accountability for patient care as a key enabler for the promotion of patient-centred care.

5.2. Factors enabling patient-centred care

In exploring professional nurses' perception of patient-centred care, a second theme emerged indicating the factors which they perceived as enabling patient-centred care.

5.2.1. Positive work environment

Both professional nurses and nurse managers emphasised the importance of staff working in an environment in which they are satisfied, and which has a positive spin-off for patient care. It was implied that if nurses were satisfied in their place of work, their relationship with patients improved, and the patients felt contented. Factors which they perceived as contributing to a positive working environment were: working in a unit where they chose to be; respect was shown by those in charge when negotiating shifts; and they provided assistance in the unit in the form of extra staff, when it was needed. The following quotation indicates their views:

'And I think the happiness of employees at work is very important. Because we spend most of our time here. So if we are not happy, you come to work, you feel drained, you don't feel like being here' (Focus group 3, page 24).

Kumar, Ahmed, Shaikh, Hafeez, and Hafeez (2013:4) states that satisfaction with one's job can affect motivation at work, career decisions, relationships with others, and personal health. Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, and Cheney (2008); and Kupperschmidt, Kientz, Ward, and Reinholz (2010) contend that healthy work environments are essential for nurses' well-being, and safe and effective patient care. Therefore a link is implied between a positive working environment and rendering patient-centred care.

5.2.2. Professional leadership

The ability of nurse managers to demonstrate exemplary professional behaviour and to address unacceptable behaviour, were indicated as ideal attributes which a nurse manager should have and which contributed to patient-centred care. The following quotation conveys these ideas:

'The operational managers, they should be exemplary. And who is able to correct an unacceptable behaviour' (Individual interview 4, page 33).

White (in Kaufman & McCaughan, 2013: 53) contends that leaders cannot be seen to turn a blind eye to poor practice, as this sets the pattern of behaviour for the whole team. Neither acknowledging nor addressing poor practice in any form has a ripple effect on the health care team and by implication has an effect on patient-centred care.

A nurse leader therefore is someone who can develop and communicate an ethical and compassionate vision of patient-centred care and inspire colleagues to emulate that vision (Kaufman & McCaughan, 2013:53). Nursing managers are essential participants in improving healthcare quality, and they need to participate in ensuring that patients receive safe, efficient, equal and patient-centred care (Frojd, Swenne, Rubertsson, Gunningberg, and Wadensten (2011:228).

5.2.3. Continuous in-service education

The need for continuous in-service education and training on different topics was mentioned by all the participants as impacting on patient-centred care. Some of the participants felt that an emphasis should be placed on teaching student nurses how to be compassionate and caring, as illustrated by the following quotations:

'We were taught to be compassionate, as if it were your own family and it was drilled into us over and over again. And somehow these youngsters [nursing students]. It seems as if it is not done anymore. So I really think we need that. They [nursing students] must be taught from the start. How to treat people and then it will be better when they qualify' (Focus group 1, page 5).

'Just continuous in-service education to the nurses. They must just be patient with the patients and the way they talk to them' (Focus group 1, page 5).

In a paper about teaching compassion in the nursing curriculum, Adamson and Dewar (2011: 42) stress that it is vital to consider how student nurses are being supported to develop compassionate caring knowledge and skills, particularly as there is strong evidence about the caring attributes that are valued by patients. Therefore incorporating the teaching of compassion and caring in the curriculum of student nurses, and in-service education programmes within the health care institutions can facilitate patient-centred care.

5.2.4. Collaborative teamwork

Nurse managers recommended working collaboratively with the interdisciplinary team, by having meetings to facilitate openness and transparency, and having an input in the rendering of patient-centred care. Another objective for these suggested meetings is for all the members of the inter-disciplinary team to focus on patient-centred care and the roles which each one plays in rendering collaborative patient care as stated below:

'In a public hospital situation, we have various stakeholders [inter-disciplinary team of health care professionals] that are providing care to the patient because the patient is our core function and business … So all the different stakeholders must focus on that patient centred care' (Individual interview 2, page 16).

The drive for collaborative practice is reinforced in the World Health Organisation's Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice (Gilbert, Yan, & Hoffman, 2010: 13) which notes the importance of collaborative teamwork within the interdisciplinary team for the delivery of effective health care. In the framework it is stated that collaborative practice in health-care occurs when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds provide comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, carers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings. Pelzang (2010:915) observes that patient-centred care needs inter-professional practice, and an organised inter-professional education programme is essential to achieve this. Therefore working collaboratively within an interdisciplinary team is viewed as enabling patient-centred care.

5.3. Barriers to patient-centred care

As a means of emphasising what patient-centred care should be, participants shared what they experienced as care which was not patient-centred care. The participants explained their frustrations of being unable to practice patient-centred care because of the numerous barriers that they are faced with in a public hospital.

5.3.1. Resources

Participants voiced their frustrations with regard to the non-appointment of staff in the face of staff shortages, the resultant increased workload, as well as limited equipment, impacted on them rendering patient-centred care. The following quotations attest to the lack of resources:

'Yes, there are challenges in the public sector to rendering care. Firstly, there is shortage of staff, doctors and nurses and all categories (Individual interview 2, page 19)'.

'If people retire or resign, they don't replace those people. It puts more strain on those who are left behind' (Focus group 2, page 13).

'I think also the limit on equipment and the stock that we don't always have is also limiting us. Also medication.' (Focus group 1, page 6).

Research conducted by Longmore and Ronnie (2014:369) regarding human resource management found that severe staffing difficulties in a medical complex in the Eastern Cape Province was experienced. Although the present Minister of Health has recognised that human resource capacity is a problem facing the health system in general and has included its improvement in the Department of Health's 10-point strategy plan, there is a concern that insufficient effort is being channelled to address the issues timeously (Longmore & Ronnie, 2014:369).

Pelzang, Wood, and Black (2010:186) found that shortage of staff and overwork were the main barriers to patient-centred care observed in the practical setting. Participants indicated that they cannot render patient-centred care effectively if they were overworked and tired. A link can therefore be made between the shortages of staff and the ability to render adequate patient-centred care.

Experiencing shortage of basic necessities such as soap, hand paper towels, and functioning equipment, has been cited by participants as factors which impeded the rendering of patient-centred care and quality care. In a study exploring nurses' perceptions and understanding of patient-centred care, the nurses stated that limited resources and inadequate staff served as barriers to rendering patient-centred care (Pelzang, 2010:192). In research conducted by Papastavrou, Andreou, Tsangari, and Merkouris (2014: 2) the authors state that the lack of resources when combined with the invisibility of caring could lead to negative outcomes for patients.

5.3.2. Administrative work

The increase in administrative work for nurses was cited by participants as a barrier to rendering patient-centred care, as a substantial amount of time is spent on documentation and writing. The increased time spent with documentation meant less time spent with patients.

'All the administration, all the nursing processes, all the record-keeping, everything has increased actually. So that has taken us away from the patient.' (Focus group 2, page 12).

In a study by Ammenwerth and Spötl (2009:81), the researchers found that a substantial proportion of working time (26.6%) was dedicated to documentation in a department of internal medicine, 22.4% of which was for clinical documentation, and 4.2% for administrative documentation. The time for direct patient care was 27.5%, which was only slightly higher than the time spent for documentation. The findings relate to the responses by the participants that the amount of time spent with documentation has taken them away from spending more time with the patients, and therefore rendering patient-centred care.

5.3.3. Unprofessional behaviour

The participants in the present study acknowledged that there are some nurses who are rude to the patients, and that this constitutes not only unprofessional behaviour, but displays a lack of nursing ethos. The harsh manner in which some nurses communicate with patients causes patients to feel upset and afraid and ultimately they are less likely to communicate their needs, as indicated by the quotations:

'Like sometimes there are nurses who are rude and then the patient gets upset and everything goes wrong' (Focus group 1, page 1).

'Nurses will shout at them. That is why they (patients) are afraid to say what worries them' (Focus group 1, page 6).

In a study by Jangland, Gunningberg, and Carlsson (2009: 13) to describe patients' and relatives' complaints about their encounters in health care, threatening a patient's dignity was described in some reports, when professionals abused their position in relation to the patient. Disruptive and intimidating behaviours which include rude language and hostile behaviour among health care professionals can contribute to poor patient satisfaction (Nadzam, 2009:186). Unprofessional behaviour displayed by nursing staff serves as a barrier to rendering effective patient-centred care.

6. Limitations of the study

The research only included public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay and thus research results could not be generalised to private hospitals. Although the research took place at four public hospitals in Nelson Mandela Bay, Eastern Cape Province, other important information could possibly have been obtained if a wider research population had been involved in the study.

7. Recommendations

Arising from the findings in the study, the following nursing education, practice and research recommendations were made:

7.1. Nursing education

It is recommended that more emphasis be placed on patient-centred care in both under- and post-graduate programmes and in-service education programmes regarding patient-centred care in the various units in public hospitals. Short learning programmes should be developed for all categories of nurses addressing the aspects which facilitate and serve as barriers to patient-centred care.

7.2. Nursing practice

Small bedside-group presentations involving the interdisciplinary team to encourage collaborative teamwork to facilitate patient-centred care is recommended. Practices such as treating the patient with love and respect, involving the patient and the patient's family in decision-making and demonstrating respect for the patient's values, culture and needs are recommended. Nurse managers should be aware of their leadership styles and the effect of positive role-modelling with regard to professional conduct, open communication, and establishing a positive work environment to facilitate patient-centred care. It is recommended that nurse managers become skilled in human and material resource management, including administrative workload of nursing staff, in order to effectively address the challenges encountered which serve as barriers to patient-centred care.

7.3. Research

The development of a best practice guideline to render patient-centred care in public hospitals is a logical point of departure for further research. Thereafter the implementation of the guideline as an intervention study is an area of research, followed by an evaluation study of the effect of the intervention on patient-centred care.

8. Conclusion

Professional nurses have a definite understanding of patient-centred care and highlighted the factors enabling and serving as barriers to patient-centred. Factors which serve as barriers surfaced as a definite concern which needs to be addressed for patient-centred care to be rendered in public hospitals by professional nurses. Thus, the development of a best practice guideline to render patient-centred care in public hospitals is a logical point of departure.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

References

Adamson, E., & Dewar, B. (2011). Compassion in the nursing curriculum: making it more explicit. Journal of Holistic Healthcare, 8, 42e45 (Affiliations). [ Links ]

Aiken, L., Clarke, S., Sloane, D., Lake, E., & Cheney, T. (2008). Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 38, 223e229. [ Links ]

Ammenwerth, E., & Spötl, H. P. (2009). The time needed for clinical documentation versus direct patient care. Methods Information Medicine, 48, 84e91. [ Links ]

Arora, N. K. (2003). Interacting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians' communication behavior. Social Science Medicine, 57, 791e806. [ Links ]

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2010). Patient-centred care: Improving quality and safety by focusing care on patients and consumers. Canberra: Biotext. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. (2014). The practice of social research (14th ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Blackman, R. (2011). Understanding culture in practice: reflections of an australian indigenous nurse. Contemporary Nurse, 37, 31e34. [ Links ]

Bulletin of the World Health Organisation. (2010). Bridging the gap in South Africa. 88 pp. 797e876). [ Links ]

Chenoweth, L., Jeon, Y., Goff, M., & Burke, C. (2006). Cultural competency and nursing care: an Australian perspective. International Nursing Review, 53, 34e40. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Lincoln: Sage. [ Links ]

Dowling, M. (2004). Exploring the relationship between caring, love and intimacy in nursing. British Journal of Nursing, 13, 1289e1292. [ Links ]

Eastern Cape Health Crisis Coalition. (2013). Death and Dying in the Eastern Cape. An investigation into the collapse of a health system. http://www.section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/SECTION27-report-redacted.pdf Accessed 05.11.2013. [ Links ]

Epstein, R. M., & Street, R. L. (2007). Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute. [ Links ]

Frojd, C., Swenne, C. L., Rubertsson, C., Gunningberg, L., & Wadensten, B. (2011). Patient information and participation still in need of improvement: evaluation of patients' perceptions of quality of care. Journal of Nursing Management, 19, 226e236. [ Links ]

Gilbert, J., Yan, J., & Hoffman, S. (2010). A WHO Report: Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [ Links ]

International Alliance of Patients' Organizations. (2007). What is Patient-centred care? London: IAPO. [ Links ]

Jangland, E., Gunningberg, L., & Carlsson, M. (2009). Patients' and relatives' complaints about encounters and communication in health care: evidence for quality improvement. Patient Education and Counseling, 75, 199e204. [ Links ]

Kaufman, G., & McCaughan, D. (2013). The effect of organisational culture on patient safety. Nursing Standard, 27, 50e56. [ Links ]

Kumar, R., Ahmed, J., Shaikh, B., Hafeez, R., & Hafeez, A. (2013). Job satisfaction among public health professionals working in public sector: a cross sectional study from Pakistan. Human Resources for Health, 11, 2e5. [ Links ]

Kupperschmidt, B., Kientz, E., Ward, J., & Reinholz, B. (2010). A healthy work environment: it begins with you. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 15. Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol152010/ No1Jan2010/A-Healthy-Work-Environment-and-You.html. [ Links ]

Kvale, K., & Bondevik, M. (2008). What is important for Patient- Centred Care? A qualitative study about the perceptions of patients with cancer. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 22, 582e589. [ Links ]

Levinson, W., Lesser, C., & Epstein, R. (2010). Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health affairs, 29, 1310e1318. [ Links ]

Longmore, B., & Ronnie, L. (2014). Human resource management practices in a medical complex in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: assessing their impact on the retention of doctors. South African Medical Journal, 104, 368e371. [ Links ]

Luxford, K., Safran, D., & Delbanco, T. (2011). Promoting patientcentered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in health care organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 23, 510e515. [ Links ]

Matteliano,M.,&Street, D. (2012).Nurse practitioners' contributions to cultural competence in primary care settings. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 24, 425e435. [ Links ]

Mayosi, B., & Benatar, S. (2014). Health care in South Africa d 20 years after Mandela. New England Journal of Medicine, 371, 1344e1353. [ Links ]

Mitchell, M., Chaboyer, W., Burmeister, E., & Foster, M. (2009). Positive effects of a nursing intervention on family-centered care in adult critical care. American Journal of Critical Care, 18, 543e553. [ Links ]

Nadzam, D. (2009). Nurses' role in communication and patient safety. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 24, 184e188. [ Links ]

Papastavrou, E., Andreou, P., Tsangari, H., & Merkouris, A. (2014). Linking patient satisfaction with nursing care: the case of care rationing e a correlational study. Biomed Central Nursing, 13, 1e10. [ Links ]

Pelzang, R. (2010). Time to learn: understanding patient-centred care. British Journal of Nursing, 19, 912e917. [ Links ]

Pelzang, R., Wood, B., & Black, S. (2010). Nurses' understanding of patient-centred care in Bhutan. British Journal of Nursing, 19, 186e193. [ Links ]

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Robinson, J. H., Callister, L. C., Berry, J. A., & Dearing, K. A. (2008). Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20, 600e607. [ Links ]

Sebugwawo, M. (2012). Service delivery protests in South Africa: lessons for municipalities. Service delivery review, 9, 7e8. [ Links ]

Shaller, D. (2007). Patient-centered care: What does it take? common wealth fund. Saskatoon SK: Access Consulting Ltd. [ Links ]

South Africa. (1997). White paper on transforming public service delivery (Batho Pele White Paper). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

South Africa. (2003). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa second amendment act, No. 3 of 2003. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Streubert, H. J., & Carpenter, D. R. (2011). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott. [ Links ]

Van Rooyen, D., Jordan, P., Brooker, C., & Waugh, A. (2009). Foundations of nursing practice (African edition). Edinburg: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Williams, D. (2012). Hospitals on brink of collapse in Eastern Cape. The Times, 20 September. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation. (2007). People centred heath care. A policy framework. Geneva: WHO Press. [ Links ]

Received 8 July 2015

Accepted 5 May 2016

Available online 24 September 2016

Peer review under responsibility of Johannesburg University.

* Corresponding author. Department of Nursing Science, School of Clinical Care Sciences, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, P.O. Box 77000, Port Elizabeth, 6031, South Africa.