Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versão impressa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.21 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2015.05.005

The GAMMA® nursing measure: Its calibration for construct validity with Rasch analyses*

Hendrik J. LoubserI, II, 1; Daleen CasteleijnIII, *; Judith C. BruceI, 2

ISchool of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, 7 York Road, Parktown, 2193 Johannesburg, South Africa

IISouth African Database for Functional Medicine, Box 2356, Houghton, 2041 Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, 7 York Road, Parktown, 2193 Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The GAMMA nursing measure was developed to routinely score a person's ability to independently perform activities of daily living. The nursing utility of the scale has been established as being satisfactory and it has been recommended that its use be extended to home-based care where restorative nursing is required for rehabilitation and elderly care

PURPOSE: To subject the GAMMA nursing measure to the Rasch Measurement Model and to report if the measure can function as an interval scale to provide metric measurements of patients' ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living

METHOD: A quantitative design was followed whereby GAMMA raw scores were collected from persons (n = 428) living in seven retirement villages and patients (n = 334) receiving home-based care after an acute or sub-acute nursing episode. In most of the retirement villages only cross-sectional data were collected; however, in the home-based care patients both admission and discharge data were collected. The data were prepared for Rasch analyses and imported into WINSTEP® Software version 3.70.1.1 (2010). Persons with extreme scores were eliminated, resulting in a final sample of 570 persons. The calibration and analyses of the final reports are illustrated with figures and graphs

RESULTS: The Rasch analyses revealed that the GAMMA functions optimally as an interval scale with a four-category structure across all eight items, rather than a seven-category structure as originally intended. Overall, the GAMMA satisfies the Rasch Model with a good to excellent fit

Keywords: Gamma, Nursing, Measure, Validity, Rasch, IADL, Gerontology, Rehabilitation

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Person-centred nursing became a popular new directive in gerontological nursing in 2001 (McCormack & McCance, 2006). It consisted of four key components which became the mainstay for good gerontological nursing practice. These four components comprise the attributes of the nurse, the care environment or context in which care is delivered, person-centred processes, and the care delivered through a range of activities (Nolan, Davies, Brown, Keady, & Nolan, 2004). The assumption was that good person-centred nursing results in good patient outcomes. Some years later, Slater, McCormack, and Bunting (2009) went further and developed a measurement tool, the Nursing Context Index (NCI), which measured the improvement in nursing work conditions when person-centred nursing is applied. The NCI thus enhanced the person-centred nursing approach to increase nursing work conditions and nursing satisfaction. According to Slater et al. (2009), the NCI revealed that nursing work conditions improved when the person-centred nursing framework was implemented in gerontological practice. In other words, person-centred nursing improves the nursing outcomes. What seems to be a problem in the clinical setting though is that nurses can measure how good they are in caring, but not how effective their caring is for their patients. There seems to be a lack in empirical evidence that good person-centred nursing care correlates with good patient outcomes. Nurses seem to believe that good nursing care correlates positively with good patient outcomes. But is this true? The answer is not known as validated routine nursing measures of patient outcomes are not available.

Nurses often find themselves inattentive within the multidisciplinary team meetings when restorative issues on patient functional improvement are discussed (Loubser, 2012). Yet, nurses observe patients continuously and are thus in an ideal position to proactively inform and guide the team on patient functioning and progress in independent execution of activities of daily living. However, in multidisciplinary meetings they seem to lose their patient advocacy role and take a supportive rather than a leading stance within the team (Ghebrehiwet, 2012). This absence of active nursing participation when restorative strategies and techniques are discussed is a major barrier to effective health team functioning and can impact on the success of person-centred care. This may also give rise to the first concern that good person-centred nursing may not necessarily correlate with good patient outcomes. Loubser (2012) proposes that the reason nurses do not fully participate in the multidisciplinary process is because they are not privy to patient evidence-based measurements to manage the patient's progress towards independent execution of activities of daily living.

The GAMMA nursing measure (hereafter referred to as the GAMMA) has been reported by Loubser, Bruce, and Casteleijn (2014) as an instrument that measures the ability of a patient to perform activities of daily living such as meal preparation, running errands, commuting and emotional stability. It has a high acceptance and usefulness level among community-based nurses to be used routinely, i.e. it has high nursing utility ratings (Loubser et al., 2014). Further, it provides routine patient evidence-based scores to enhance nurses' confidence in their patient outcomes. Loubser (2012) proposed that the empirical evidence provided by the GAMMA could provide the nurses with the ability to reclaim their patient advocacy role, their accountability character and the management identity required by the NCI. To achieve this, the GAMMA's construct validity as an accurate nursing measure had to be demonstrated. The purpose of this article is thus to report on the construct validity and reliability of the GAMMA.

1.2. The Rasch Measurement Model (RMM)

The Rasch Measurement Model (RMM) was conceptualised by Georg Rasch, a Danish mathematician, in the 1960s. He studied the relationship between human ability and item (or task) difficulty, and developed a mathematical formula to calculate this relationship (Rasch, 1960). In essence, this formula expresses the probability that a person with a certain level of ability will pass items in a test with a certain difficulty level. In other words, persons with low ability will pass items with low levels of difficulty and vice versa. He intended his formula to be applied in the field of education, but his probability theory is so fundamental that it has been used in the healthcare sciences since the late 1990s. The RMM is particularly useful in healthcare where assessments contain rating scales with ordinal levels of measurement. For example, when a person's ability to dress himself is assessed and scored, the possible categories on the rating scale are described as 1 - completely unable, 2 - able with much assistance, 3 - able with minor assistance, 4 - independent with use of assistive devices, and 5 - completely independent. The disadvantage of ordinal rating scales is that it is not legitimate to sum the scores of the items in an assessment to obtain the total score and treat it as an interval scale because the distances between the categories are not equal. One may only sum scores that are on an interval level of measurement, such as millimetres on a ruler (Iramaneerat, Smith, & Smith, 2008). The RMM transforms ordinal scores to interval or linear scores, provided that the data fit the requirements of the RMM (Bond & Fox, 2007). If the scale fits the RMM, the scale then has the ability to provide linear interval measurements that can be used in further linear calculations. If the fit to the RMM is poor then the RMM has the ability to guide the developer along a diagnostic pathway to identify structural mistakes and to make suggestions how to calibrate it until an optimal RMM fit is attained (Linacre, 2004). If the RMM reveals no fit with the new scale, the RMM will declare the scale as non-functional and not remedial (Bond & Fox, 2007).

Today there are Rasch centres of excellence worldwide supporting robust Rasch systems to guide scale developers to achieve excellence in certifying construct validity of new measurements in healthcare (Tennant & Conaghan, 2007). The RMM is well reported in the global classic and current literature (Bond & Fox, 2007; Kottorp, 2003; Linacre, 2010; Masters, 1982). Kersten and Kayes (2011) described the essential assumptions and concepts of the RMM in an easy to understand format with examples from healthcare assessment. Readers are encouraged to read this publication for an introduction to the RMM.

1.3. Research purpose

The research purpose was to subject the GAMMA to the RMM and to report whether the GAMMA can function as an interval scale to provide metric measurements of patients' ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living.

1.4. Research objectives

The objective was to follow the diagnostic pathway provided by the RMM to a point where the GAMMA could optimally fit RMM.

The diagnostic pathway consisted of the following questions:

- Do the categories of the items of the GAMMA function as intended?

- Do the items fit the RMM?

- Is there a spread of easy to difficult items along the construct?

- How reliable is the scale?

1.5. Instrument discussion

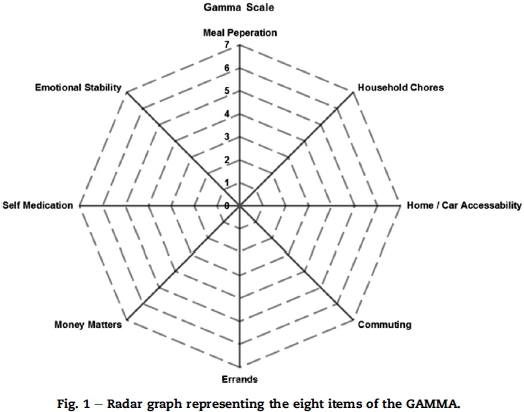

A brief description of the GAMMA follows to provide a basic understanding of the items and scoring of the GAMMA. The underlying construct or latent trait that the GAMMA intends to measure is known as the instrumental activities of daily living, i.e. those activities that a person performs that are instrumental in their independent functioning on a daily basis. There are eight items that represent the underlying construct, namely meal preparation, household chores, home (and car) accessibility, commuting, running errands, money matters, self-medication and emotional stability. Each of the eight items has seven categories. These categories are based on the amount of nursing assistance a patient requires during the restorative nursing process, e.g. 1 = patient does none of the activities, 2 = patient is doing less than 50% of the activities, 3 = patient is doing 50-80% of the activities, 4 = needs help with a specific task or occasional help, 5 = needs help outside definition, 6 = only needs something, 7 = OK. These seven categories are consistent across the eight items. The eight items, each with their seven categories, are visually displayed in a graph depicted in Fig. 1. The scores of all the items are summed to obtain a total score. The maximum score is thus 56 and the minimum eight.

Nursing staff were required to attend a one-day training workshop before they could use the GAMMA. Training included the definition and description of the GAMMA items and how to score each item. Thereafter, participants were tested using three cases (descriptions of patients with problems in activities of daily living) and were required to pass each case with at least 80% before being accredited as a GAMMA user. This training, testing and accreditation process is necessary for the correct use of the GAMMA and to ensure its reliability. The GAMMA® is the property of the South African Database for Functional Medicine (SADFM). Licensed use is available provided the facility is trained, tested and credentialed in the correct application of the GAMMA (SADFM RSA patent registration number 2008/09086).

1.6. Contribution to the field of nursing

The GAMMA is a standardised routine nursing measure of a person's independent living abilities. It provides nurses with empirical patient evidence-based data on patient outcomes to enhance nursing confidence in their patient outcomes. The researchers postulated that this standardised nursing evidence would enhance nurses' confidence to reclaim their patient advocacy role, their accountability character and their management identity as required by the International Council of Nursing (Ghebrehiwet, 2012).

2. Research method

2.1. Design

A quantitative design was followed whereby GAMMA raw scores were collected and analysed using Rasch analysis.

2.2. Data collection

GAMMA observational data on two groups of persons were pooled for analysis. The first group consisted of 428 older persons' GAMMA scores in seven retirement villages. Only those living independently in their cottages and those living in an assisted living environment were included in the sample. The residents in frail care units were excluded as they were unable to perform instrumental activities of daily living and received total care. The resident nurses in the retirement village collected the GAMMA data. The nurses were required to observe the residents routinely in their homes and their activities of independent living, and to render support where needed. They were trained, tested and accredited with the help of a training manual in the application of the GAMMA.

They then set out to observe, score and record all independent and assisted living residents in their villages. Originally the intention was to use cross-sectional measurements as a baseline for future longitudinal studies; however, some nurses did follow-up assessments as they became used to the GAMMA observational framework and recognised changes as they happened. Thus both cross-sectional and longitudinal observational scores were obtained from some residents rendering a total of 468 responses in the retirement village grouping (one single resident might have had more than one score, e.g. admission, intermediate or discharge score).

The second data set were collected on 334 patients receiving home-based care by a home-based care agency nurse. The home-based care agency nurse was trained, tested and accredited to use the GAMMA, and scored patients longitudinally on admission, intermediate and at discharge. Patients were referred to the agency by medical schemes for convalescent care after an acute hospital or rehabilitation episode of care. All adult patients admitted into the home-based care programme over a period of one year were scored. No exclusions were made based on any criteria except age (<18). In total, 689 responses were recorded (one single patient might have had more than one score, e.g. admission, intermediate or discharge score).

The data of both groups were collected on hard copy and in most cases entered by the nursing services into a web-based software application. The rest were faxed to the researcher for capturing. The pooled raw data from both groups totalled 1157 responses.

2.3. Data analysis

The WINSTEP® Software version 3.70.1.1 (2010) was used to perform the analysis. A licence to use the software was procured through www.WINSTEPS.COM (Winsteps, 2010). Other software packages are available for Rasch analyses but WINSTEP was preferred as the first author was trained in RMM with WINSTEPS.

The category probability curves were analysed to determine if they functioned as intended. Ideally, each category or point on the rating scale should reflect the increasing amount of the trait that is being measured. For instance, when a person obtains a score of 2 on the GAMMA, it indicates that they "passed" category 1 on the scale. There must be a logical ascending order of the categories.

The indices selected for reporting on the fit to RMM were the information-weighted mean square (INFIT MNSQ) and outlier-sensitive mean square (OUTFIT MNSQ) values, the point-measure correlation (PT MSE CORR), and the variance explained by measure. The INFIT and OUTFIT MNSQ values are the core statistics to verify if the scale fits the RMM or not. Linacre (2010) suggests an INFIT MNSQ value of 1. Values below 1 indicate variation and unexplained responses. OUTFIT MNSQ values should range between 0.5 and 1.7 as reasonable for fitting items. Unidimensionality was inspected on the amount of variance explained by the Rasch dimension as the first factor. A variance of 60% or greater indicates one dimension and thus supports the unidimensionality of a scale (Linacre, 2010).

Ideally, a scale should have a spread of easy, medium difficult and difficult items to cover all levels of ability of the population under study. If the scale has too many easy items, people with higher ability will all pass the items and this will result in the ceiling effect, or if there are too many difficult items, most people will not pass the items and will be pooled towards the lower end resulting in the floor effect. The scale must thus be targeted to the persons who are likely to be subjected to the scale. WINSTEPS provides a variable map to indicate the difficulty of items against the ability of the persons in the sample, also called a person-item map. The mean location for persons around the value of 0 indicates a well targeted scale (Tennant & Conaghan, 2007).

The person and the item separation indices were used to determine if the scale distinguished consistently between people with different levels of ability in the underlying construct and whether there was a good range of item difficulties to cover the levels of ability. The separation index is similar to a t test between two groups; the larger the index, the more distinct the levels of ability can be distinguished. A person separation index of 1.5 is viewed as acceptable, 2.0 as good and 3.0 as excellent (Duncan, Bode, Min Lai, & Perera, 2003). Reliability of persons and items resembles the Cronbach alpha with a reliability index above 0.7 as acceptable, 0.8 as good and 0.9 as excellent (Linacre, 2004).

2.4. Data preparation and sample size

The first concern in the data preparation was data dependency as several persons had more than one score (admission, intermediate or discharge score). The Rasch analysis requires responses in all the categories of the scale that are independent. The GAMMA has seven categories for each item and the ideal sample should have 10 responses per category. Equal representation across all categories for each item is never possible but this serves as a guideline. A sample of approximately 560 persons was thus required. A sample was then selected based on the frequency distribution of the total admission, intermediate and discharge observations, making sure that persons do not appear more than once. Therefore the final data set for analysis had 635 observable single raw scores of 635 persons.

At this stage consideration was given to Linacre's (2010) suggestion that clinical observations with under-fitting responses over 1.7 mean square logits are usually associated with careless mistakes that are too unpredictable for Rasch analysis. These should thus be removed for calibration. Therefore the most miss-fitting data (<1.7 MNSQlogits) were removed leaving the remaining data set of 570 responses free of under-fitting data. This new raw data set of 570 person observations were used for the Rasch analysis of the GAMMA.

3. Ethical considerations

3.1. Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand and an ethical clearance certificate with the number M 10524 was obtained. Written permission was obtained from the clinical managers of the participating facilities.

3.2. Informed consent

Since the researchers used scores from the nursing records, consent was not required from individuals in this regard. Nursing care was provided as usual and patients were not asked to do anything outside the normal routine. Participating nurses received information about the study and consented to participate. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured by preventing any linkages of the research data which could reveal the identity of the participants (patients, nurses or the facilities included in this study). In the data base all patient identifying information was encrypted.

4. Results

4.1. Results on category functioning

The first objective was to test if the categories on the scale functioned as intended. This was done by checking for disordering of categories by running the category probability curves of the eight items. The results showed a disordering of categories across all the items. Fig. 2 shows the category functioning of three of the eight items which showed clear disordering. The disordered curves are those on the left-hand side. From the probability curves it became clear that the nurses had difficulty in observing seven different categories of independent living. It seems that they were not able to distinguish between two categories (e.g. 2 and 3), the amount of assistance a person needed in a specific task. However, the analysis revealed exactly where (which category) the nurses had problems with distinguishing between categories and suggested collapsing with neighbouring categories. When this was done, the ordering of categories improved significantly. Items on the right side of Fig. 2 show ordered categories. (Only three of the eight items are displayed due to space limitations.)

The results of the analysis on the functioning of the categories are illustrated in Table 1. The data in the "New structure" column in Table 1 must be interpreted as follows: Each item originally had seven categories in the order of 1234567. The analysis concluded that nurses were unable to differentiate satisfactorily between two neighbouring categories (say 2 and 3) and suggested that these two categories would function better as one category. For this reason problematic categories were collapsed into one category. Meal preparation will be explained to illustrate the point. The category curves of meal preparation in Fig. 2 (left side) showed disordering (curves do not intersect in an ascending order). The curve of category 6 intersects first with category 3 while it should first intersect with category 5 (its adjacent category). This means that a higher category presents a lower level of ability. The categories of meal preparation are clearly disordered. Collapsing of categories was thus necessary. When categories 2, 3 and 4 were collapsed as one category and categories 5 and 6 into one, the new structure was 1222334. Meal preparation thus changed from a seven-category structure to a four-category structure.

After the categories of all the items were successfully collapsed, the peaks of the new categories were all in ascending order along the latent variable of each item. Furthermore, the cross-over points between the categories were ordered, e.g. the descending curve of each category clearly crosses the ascending curve of the neighbouring category.

The new structure was then analysed against guidelines suggested by Linacre (2004) to ascertain whether it was actually functioning well.

Linacre's (2004) guidelines:

- A minimum of 10 observations is required in each rating category with a fair distribution across the rating categories. The GAMMA sample fulfilled this guideline as can be seen in Table 1 (OBSVD COUNT). Items 1, 2, 3 and 4 showed very good distributions while items 5, 6, 7 and 8 showed good distributions.

- The outfit mean square (Outfit MNSQ) values for the categories should be less than 2.0 (Linacre, 2010). The Outfit MNSQ of all the items of the GAMMA was less than 2.0 as is evident in Table 1. Category 1 of the item Emotional stability was the highest with exactly 2.0 which may indicate that haphazard rating occurred with this category.

- The thresholds advanced orderly with categories after collapsing the items to a four-category structure as seen in the column Structure calibration. These thresholds correspond with the intersecting points between the curves in Fig. 2 (right side).

- Step difficulties for a five-category scale should advance with 1.0 logit. The GAMMA's new four-category structure contained three thresholds per item. Thresholds are those distances between the scores, thus a four-category scale contains three thresholds. Linacre's guideline is that the distance of a threshold should be 1.0 logit. The GAMMA now has 24 thresholds (eight items multiplied by 3 thresholds per item). Of all these thresholds 21 advance by at least 1.0 logit (see Structured calibration column in Table 1), indicating that these neighbouring categories are performing within range as suggested by Linacre (2004), and are clearly separable and functioning independently. However, of the three underperforming categories one was in the marginal range (item 5: Errands advancing with 0,80 logits), one outside the marginal range (item 7: Self-medication advancing with 0.64 logits) and one in the unacceptable range for measurement (item 6: Money matters advancing only 0.21 logits). This narrow distance might increase the difficulty in distinguishing between two categories in the Money matters item.

Step difficulties should not advance above 5.0 logits. If the distance between two categories is too wide, it may indicate that another category should be added. None of the GAMMA thresholds exceeded the 5 logit margins. Item 2 was the highest at 4.48 logits. As a result of this investigation into the new category structures of all the items, it was concluded that it was ordered and worked as intended, and therefore the four-category structure was accepted for the GAMMA.

4.2. Results on item functioning

The second objective was to study the fit of the GAMMA items to the requirements of the RMM.

The infit and outfit MNSQ values indicated that all items were between the range of 0.5 and 1.7 except for item 8 (Emotional stability) with an infit MNSQ of 1.8. Infit statistics are sensitive to unexpected responses by persons on items targeted for their ability level. In other words, one would expect the person to have "passed" the item. Item 8 falls slightly outside the range, which may warrant a revision of the item. Outfit statistics are sensitive to outliers or extreme responses. Since all the extreme persons were removed before the analysis, this may be the reason why all items fitted between the range of 0.5 and 1.7.

Point measure correlation (PTMSE CORR) per item showed strong correlations close to 1.0. This indicated good discrimination between items and that items functioned as expected. This is an indication that these items contribute to a unidi-mensional construct of independent living, thus all contributing to the latent trait.

The result of variance accounted for supported unidi-mensionality of the GAMMA. A percentage of 70.2 accounted for the Rasch dimension as the first factor (see Variance explained by Measure column in Table 2).

The third objective was to determine if there was an adequate spread of easy to difficult items that corresponded with the ability levels of persons. A variable map (Fig. 3) with person ability (left) and task difficulty (right) was constructed for this reason. This vertical line map tests the dependability of the scale developer's construct, e.g. does the person ability match up with the task difficulty. The mean difficulty estimate location for items is set at 0 logits. Item categories should be arranged around the 0 logit in the case of persons with medium ability overlapping around the 0 logit. Fig. 3 shows that most of the GAMMA items were situated near 0 logits. The item emotional stability was the most difficult task to score while the item household chores was the easiest. Approximately one third of the persons clustered at the top end with no items overlapping that level of ability and the same happened at the lower end of the scale. This phenomenon of clustering of persons at the top (ceiling effect) and at the bottom (floor effect) will be discussed later.

The fourth objective was to test the reliability and separation indices on items and persons. Reliability values well above 0.7 for persons (0.91) and items (0.99) were achieved.

The GAMMA thus successfully differentiates between persons and items. The person separation index was well over 2.0 for persons (3.10) and items (10.29), indicating a good range of item difficulty that covered a wide range of functional ability in the sample.

5. Discussion

The RMM revealed that the GAMMA can function structurally as a measure of independent living without being divided into subunits of measurement for further accuracy. It also functions well with the designed eight items. However, it required some collapsing of the categories to achieve more accurate nursing observations. Overall, the GAMMA achieved very good results with the Rasch Model.

Firstly, the ceiling and floor effect seen in the RMM variance map in Fig. 3 must be explained as it suggests that the sample selection does not fully fit the anticipated range of the scale. First of all, all persons living independently in selected retirement villages were scored. This included numerous newly retired persons being fully independent. No selection criteria were used to select an appropriate sample for the range of the scale, e.g. persons older than 75 years. Secondly, a floor effect was noticed because a substantial number of home-based care patients were included in the database and they were scored while convalescing from acute care. This made them incapable of participating in any of the independent living activities at the time of scoring.

Finally, the GAMMA was designed with the nurses' input as they observe and experience the clinical restorative progression of patients on their pathway to independence. The RMM did not fully correspond with the nursing observations of seven categories. Clinical implications of this must be considered. Must the developer change the GAMMA and thereby interfere with the nursing interpretation of patient functioning, or should the original nursing scores be adjusted in the software to suit the accuracy of the RMM model? The second option was finally taken. As the original GAMMA data are entered into the software, the data will be converted into the accurate Rasch data. Nurses thus follow their nursing judgement or logic when collecting GAMMA data; the software then converts the raw GAMMA data into accurate RMM data.

With the new knowledge that the GAMMA satisfies the RMM and therefore successfully transforms ordinal scales into interval measures, new opportunities for the nursing profession are available. With the GAMMA's pre-existing high utility rating as a routine measure with nurses in retirement villages (Loubser, 2012), the GAMMA is a workable option to fill the gap in the person-centred nursing model of McCormack and McCance's (2006) gerontological nursing. The GAMMA can provide the additional patient-outcomes information required. The GAMMA can also empirically verify the correlation between the person-centred nursing model and the actual results achieved in patient improvement. Moreover, it is expected that the GAMMA might assist the nurse to focus more on patient outcomes and thereby enhance the patient-centred model of nursing. As the nurses can now provide empirical evidence of change in patients' independent living outcomes as a direct consequence of their nursing inputs, their job satisfaction may increase. This would result in better recordings with Slater et al.'s (2009) Nursing Context Index (NCI) measurement tool.

Furthermore, the GAMMA measure could guide nurses to fully contextualise what is required to manage the patient environment in maximising the patient's independence. Once nurses have mastered this measure, their voices will be heard and respected in multidisciplinary meetings. They will be able to take full control of their intended advocacy role again. The GAMMA should thus greatly satisfy the concerns of Ghebrehiwet (2012).

6. Limitations

Although the credentialing process to some degree improves the quality of the data, the GAMMA must still be considered a new experience in the nursing process and skills will improve over time. Although the Rasch results are accurate, further calibration with better data samples might result in minor changes to the current reporting.

As this is a first Rasch analysis to verify if the GAMMA has potential to function as a valid nursing measure, further advanced Rash analyses need to be done overtime to establish rater reliability with the WINSTEP FACETS®.

7. Conclusion

The situation where nurses apply nursing outcome measures when they develop programmes to improve patient outcomes is not well understood. The inference that good nursing outcomes correlate with good patient outcomes requires further evidence. The GAMMA is a valid tool that may provide the much needed evidence in restorative nursing.

Author's contribution

This article was based on the primary research done by HJL under supervision of JCB and DC for the PhD thesis: The validation of nursing measures for patients with unpredictable outcomes. The draft was formulated by HJL and JCB and DC contributed to the finalisation of the article.

REFERENCES

Bond, T., & Fox, C. (2007). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measures in the human sciences. Mahwah, New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Duncan, P. W., Bode, R. K., Min Lai, S. M., & Perera, S. (2003). Rasch analysis of a new stroke-specific outcome scale: the stroke impact scale. Archive of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation, 84(7), 950-963. [ Links ]

Ghebrehiwet, T. (2012). Helping nurses to have a voice: a conversation with Tesfa Ghebrehiwet. International Nursing Review, 59(3), 297-299. [ Links ]

Iramaneerat, C., Smith, E. V., & Smith, R. M. (2008). An introduction to Rasch measurement. In J. W. Osborne (Ed.), Best practices in quantitative methods. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing. [ Links ]

Kersten, P., & Kayes, N. M. (2011). Outcome measurement and the use of Rasch analysis, a statistic-free introduction. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy, 39(2), 92-99. [ Links ]

Kottorp, A. (2003). Occupational based evaluation and intervention. Validity ofthe assessment ofmotor process skill when used with persons with mental retardation. Sweden: Umea University. [ Links ]

Linacre, M. (2004). Optimising rating scale category effectiveness. In E. V. Smith, Jr., & R. M. Smith (Eds.), Introduction to Rasch measurement: Theory, models, and applications. Maple Grove, MN: JAM Press. [ Links ]

Linacre, M. (2010). Practical Rasch measurement - topics course. Retrieved from http://www.statistics.com/howcoursework. [ Links ]

Loubser, H. J. (2012). The validation ofnursing measures for patients with unpredictable outcomes (Doctoral thesis). Johannesburg, South Africa: Dept. of Nursing Education, University of Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Loubser, H., Bruce, J., & Casteleijn, D. (2014). The GAMMA nursing measure: its development and testing for nursing utility. Health SA Gesondheid, 19(1), 1-9. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v19i1.749. [ Links ]

Masters, G. N. (1982). A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika, 47, 147-174. [ Links ]

McCormack, B., & McCance, T. V. (2006). Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. Journal of AdvancedNursing, 56(5), 472-479. [ Links ]

Nolan, M. R., Davies, S., Brown, J., Keady, J., & Nolan, J. (2004). Beyond 'person-centre' care: a vision for gerontological nursing. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 13(3a), 39-44. [ Links ]

Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Copenhagen: Denmarks Paedagogiske Institut. [ Links ]

Slater, F., McCormack, B., & Bunting, B. (2009). The development and pilot testing of an instrument to measure nurses' working environment: the nursing context index. Worldviews Evidence Based Nursing, 6(3), 173-182. [ Links ]

Tennant, A., & Conaghan, P. (2007). The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 57(8), 1358-1362. [ Links ]

WINSTEPS®. (2010). SWREG Inc Order Number U795629501. Retrieved from https://usd.swreg.org/cgi-bin/r.cgi?o=795629501. [ Links ]

Received 21 February 2015

Accepted 29 May 2015

* Research significance: The GAMMA is a nursing scale designed to routinely score an elderly or disabled person's ability to live independently. In this study, the GAMMA's construct validity is tested to confirm the extent to which the GAMMA can function as a standardised metric. With this known, restorative nursing has the potential to become an empirical science to calculate patient improvement, nursing performance and efficiencies of nursing service delivery.

** Corresponding author. Tel.: +27 021 717 3701. E-mail addresses: hennie@sadfm.co.za (H.J. Loubser), Daleen.casteleijn@wits.ac.za (D. Casteleijn), Judith.bruce@wits.ac.za (J.C. Bruce).

1 Tel.: +27 082 574 5129 (cell).

2 Tel.: +27 021 717 2063.