Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.20 no.1 Cape Town 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.HSAG.2015.02.003

Nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship

Anna Elizabeth Van den Heever*; M. Poggenpoel; C.P.H. Myburgh

University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Genuineness was highlighted as an important concept when nurses' perceptions of facilitating a therapeutic relationship were assessed in a study conducted in private general hospital wards. Training courses are mainly professionally orientated and little attention is given to genuineness, which is underpinned by values and influenced by culture and self-awareness. Reflection on patients' feelings enables mindfulness in the nurse-patient relationship, but nurses often act on instinct or rely on learned knowledge and skills. Despite the increased emphasis on virtue ethics and honest disclosure, hope is offered but nurses are often not honest with themselves or in their response to patients. This poses a challenge when genuineness is facilitated. In this article, nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness will be discussed.

METHOD: To assess nurses' genuineness, a quantitative, contextual, deductive and descriptive study was conducted. A purposive sample of nurses was taken from private general hospitals in Gauteng, South Africa. Nurses' (n = 181) perceptions of facilitating genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship were self-assessed on a five-point scale in a questionnaire.

DATA ANALYSIS: Descriptive statistics and non-parametric statistical techniques were used. Specific hypotheses were tested to identify whether statistically significant differences in perceptions of facilitating genuineness existed between two or more groups.

RESULTS: When groups were compared, statistically significant differences were identified in nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness with respect to age, years' experience as a nurse and qualifications. It is recommended that nurses' awareness of genuineness and its facilitation should involve learning through socialisation and self-awareness.

Keywords: Perception; Genuineness; Facilitation

1. Background

The purpose of this article is to highlight the importance of nurses' awareness of and reflection on genuineness in the nurse-patient relationship, which was explored in an

overarching research project (Van den Heever, 2012; Van den Heever, Poggenpoel, & Myburgh, 2013). As a theoretical framework, Carl Rogers' person-centred concepts of a therapeutic relationship and a systematic approach to the evaluation of interpersonal relationships (Aiken & Aiken, 1973,p. 865; Rogers, 1957, p. 100) were used. Psychological interventions tend to take the forms of facilitating, supporting and nurturing instead of teaching or controlling. During interactions with patients, nurses present themselves as being able to offer help, but they should also promote genuine interest in and respect for the patient; in other words, show that they genuinely care.

The reality today is that nurses are not always caring and genuine with themselves or with their patients in the nurse-patient relationship (Van den Heever, 2012,p.67). Little attention is given to genuineness, and training courses are mainly professionally orientated (Torres-Rivera, Phan, Maddux, Wilbur, & Arredondo, 2006,p. 2). Knowledge is necessary, but not always sufficient to facilitate understanding and promote awareness of other people. The term "nurse" will thus be used inclusively in this paper to refer to all categories of staff (professional, enrolled, auxiliary nurses and care workers) who interacted with patients in private general hospitals at the time of the research study.

There are various conditions and contexts that can facilitate nurturing. One of the conditions in a hospital is relating to vulnerable patients. Within the theoretical context of genuine empathetic understanding and caring, patients' basic psychological needs of relatedness can either be nurtured or inhibited by what others say or how they respond to each other.

Nurses are expected to have knowledge and skills, but they also become aware of feelings and emotions when engaged in real interactions with patients. In a relationship, nurses facilitate, integrate and reflect on what patients say; however, Sidney Jourard in the 1960s and 1970s proclaimed that we camouflage our true being before others to protect ourselves against criticism or rejection. Nurses, according to Menzies-Lyth (1988, p. 90), would then, instead of letting anyone know how they really feel, use various coping mechanisms or avoid answering a question to protect and defend themselves from anxiety or to hide uncertainty (Scanlon, 2006, p. 325). Uncertainty can thus unfortunately inhibit facilitation and expression of feelings.

Although it is expected of them, it is not always possible for health care professionals to have all the answers, and nurses have often expressed their fear of not knowing what to say (Reed & Fitzgerald, 2005, p. 215). In most nurses' minds there seems to be a strong connection between being a good nurse and doing the "right thing" which supports the recent popularity of virtue ethics (Begley, 2008, p. 337). Rather than focussing only on the moral actions themselves, virtue ethics looks to the person's character as the foundation and source of ethical action (Smith & Godfrey, 2002, p. 301).

Professional, ethical and therapeutic boundaries are often blurred when nurses have to come physically close enough to the patient to offer care, but at the same time also have to maintain emotional distance. Patients and their families often express hopelessness. Vague and abstract responses from nurses then may offer some hope when a patient is in despair, but also hinder self-exploration and a trusting nurse-patient relationship (Frisch & Frisch, 2011, p. 102; Arnold & Boggs, 2011, p. 19; Gilbert, 2009, p. 45). Over-involvement on the other hand, with routine and administrative tasks or sarcastic humour for example, may be used by nurses to either avoid discussing the patient's fears or maintain the nurse-patient relationship at a superficial level (Van den Heever, 2012, p. 62; Poggenpoel, 1997, p. 29).

Awareness, reflection and genuineness seem to be interrelated and therefore, being reflective of patients' verbal and non-verbal messages nurses are also being mindful of their feelings. Mindfulness is an open and undivided awareness of current experiences both internally and externally in the here and now, rather than a cognitive approach to stimuli (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 822). Mindlessness, on the other hand, is when a person refuses to acknowledge or attend to a thought, emotion, motive or object of perception (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 823).

At times during the nurse-patient interaction, nurses act on instinct when they pick up non-verbal cues, as opposed to acting according to any learned methods. Awareness or intuition therefore is an application of self-awareness and human skills by a knowledgeable person who draws on experience and insight gained from maturity (Begley, 2008,p. 338; Scanlon, 2006, p. 328).

Most health professionals are taught to be polite, kind, pleasing, socially and professionally appropriate rather than to be genuine and congruent in their relationships with themselves and their patients. Facilitating genuineness involves learning through socialisation or experiential learning (Scanlon, 2006, p. 328) and is founded in the awareness and perception of each other in an open and trusting relationship (Bozarth, 2001,p.1;Rogers, 1957, p. 95).

Honesty is often perceived as truth-telling. Practises among nurses and doctors have moved to more honest and truthful disclosure to patients, but truth-telling practises and preferences are to a certain extent a cultural artefact (Tuckett, 2004, p. 500). Then there is also the argument for or against telling the truth, which is mostly grounded in the ethical principles of the patient's autonomy and prevention of physical or psychological harm. Truth-telling and genuineness in the nurse-patient relationship is intrinsically good, and doing "good" is an ethical principle. An integral part of "doing good" in nursing, is to offer hope, yet the question still arises whether withholding the truth for the sake of having hope is detrimental or not to a trusting relationship.

According to Tuckett (2004), one ought to ask patients and their families what information they require, and to explore the cultural nature of the patient and the healthcare setting. In China, many families object to telling the truth therefore doctors and nurses seem to follow the wishes of what the family of their patients want to know (Tse, Chong, & Fok, 2003, p. 339). However, the majority of patients indicate that they want truthfulness and information about their illness which will enable them to manage their own uncertainty and allow them to make decisions for themselves (Epstein & Street, 2007; Tse et al., 2003, p. 339). Genuineness and truthfulness are virtues and characteristics which have long been perceived as being real and transparent, while honesty has been defined as truthfulness, authenticity, morality, integrity and trustworthiness (Begley, 2008, p. 337; Ashton, Lee, & Son, 2000,p.360;Rogers, 1957). Genuineness and honesty are therefore consistent with constructive relationships.

Not only is genuineness closely linked to a person's beliefs about themselves and the world, but also to honest and congruent responses to others and their moral-ethical conduct (LaSala, 2009, p. 429; Epstein & Street, 2007, p. 17). Honesty as a virtue also requires practical skills, theoretical knowledge and excellence of character (Begley, 2008, p. 336). Knowledge and skills can be acquired through learning and teaching, but attitude refers to the perception or opinion one holds about others and also towards aspects such as life and death, a mind-set and a tendency to act in a particular way due to an individual's culture, experience and temperament (Pickens, 2005, chap. 3, p. 11).

Because genuineness is a virtue and a characteristic of a person which is influenced by culture, religion and self-awareness, it is arguably underpinned by key values and beliefs (Johnson, Haigh, & Yates-Bolton, 2007, p. 366). "True" feelings can therefore only be confirmed in retrospect and with reflection. When there is a conflict between two people's beliefs, unrealistic hope may be offered but hope can then be seen as supportive or disruptive when it is actually false hope (Little & Sayers, 2004, p. 1336). In a nurse-patient relationship, nurses' perceptions are underpinned by their own culture, values and beliefs which inevitably play a role in how they perceive hope or facilitate genuineness.

Thus, there could be differences in people's perceptions of a genuine response in interpersonal processes. In the nurse-patient relationship, genuine responses can be facilitated on various levels, for example, verbalisations at a lower level tend to be false or reassuring in a disruptive way, while on a higher level, nurses facilitate genuineness by their awareness of themselves and being sincere and reflective of true feelings.

The following levels describe the underlying perceptions of how genuineness is facilitated.

Level one (1): On the lowest level of facilitating genuineness, responses are clearly unrelated to what patients are feeling at the moment; or the only genuine response is negative and appears to have a detrimental effect upon the patient. In the nurse-patient relationship, nurses may be defensive in their interaction and this defensiveness may be found in the content of their words or their voice quality (Carkhuff, 1969, p. 319).

Level two (2): On the second lowest level, false reassurance may be provided rather than expressing what one feels. Automatic day-to-day responses could have a rehearsed quality, rather than expressing what a person personally feels or means. Guilt or self-blame could be implied which can be seen as superficial and mindless, and do not form a basis for genuineness or reflective exploration of feelings (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 823).

Level three (3): No positive or negative cues are offered to indicate genuineness in response to the patient's feelings. Nurses may appear, for example, to make appropriate responses and to listen but commit nothing of themselves or do not reflect any real involvement either. When we talk about not giving up hope, for example, a person may have various levels of hope about cure, which is commonly equated with the promise of curative treatments for disease (Beste, 2005, p. 230).

Level four (4): Responses on level four (4) add deeper meaning to what patients are saying and demonstrate concern and understanding of the patient's despair. Some positive cues, although not fully expressed, indicate a genuine response and consideration for patients and their family's feelings in a non-destructive manner. Expressions allow patient autonomy and are congruent with their feelings, although they may be somewhat hesitant about expressing them fully (Aiken & Aiken, 1973, p. 865; Carkhuff, 1969, p. 319).

Level five (5): At this level, responses are spontaneous and nurses are freely and deeply themselves in a non-exploitative relationship. By listening to their fears and clarifying what patients are saying, nurses and patients are open to experiences of all types, both pleasant and hurtful. In the event of hurtful responses, nurses' comments are employed constructively to encourage further enquiry and to reflect on genuine feelings with mindfulness in a trusting relationship (Aiken & Aiken, 1973, p. 865; Carkhuff, 1969, p. 319).

Guided by the theoretical framework of the study, these levels of facilitation were operationalised in the form of scenarios (Aiken & Aiken, 1973, p. 865; Carkhuff, 1969, p. 319; Rogers, 1957, p. 100). Scenarios were structured to simulate familiar interactions between nurses and patients and to allow facilitation of genuine responses (see Table 1). Scenarios and simulation are often used for skills training related to decision-making and communication (Nagle, McHale, Alexander, & French, 2009, p. 24). The use of scenarios in this study therefore enabled the researchers to analyse nurse-patient interactions which resembled real life situations experienced in nursing practice.

2. Problem statement

Despite their training as well as an abundance of theoretical literature on ethics and the nurse-patient relationship, nurses are often described as being not "genuine" or insensitive in relation to patients' true feelings (Begley, 2008, p. 360; Moyle, 2003, p. 103; Van den Heever et al., 2013,p.6;Van Zyl, 2010, p. 94; Vythilingum, 2009, p. 450). Very little research has been done to quantify and describe nurses' awareness of genuineness. The authors of this study wanted to explore how psychological processes of reflection and genuineness are perceived by nurses. Because genuineness is a virtue and underpinned by values, the question was asked what the influence of age, qualifications or years' experience would be on how nurses perceive the facilitation of genuine responses.

3. Research aim and objectives

For the purposes of this article, nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness on five levels are discussed.

4. The research objectives

To explore and describe nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship.

To examine differences in nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness with respect to age, years' experience and qualifications.

To recommend facilitation and further research into genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship.

5. Research method

A quantitative, contextual, deductive and descriptive design was used.

6. Population and sample

Nurses from all categories working in three private general hospitals in Gauteng, South Africa, were considered for the research study (Van den Heever, 2012). Nurses were purposively selected from all the shifts. Due to patients being sedated and time constraints, nurses working in operation theatres and intensive care units were excluded from participation. All categories (professional, enrolled, auxiliary nurses and care workers) were included in the sample because of their nurturing role in a nurse-patient relationship, and with the objective of assessing their perceptions with regard to differences in age, qualifications and experience.

7. Data collection and instrument

The data collection process was conducted at the three private hospitals. Patient care was a priority and had to be considered when nurses were called to participate in the research.

Self-report data was collected by means of a questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of biographical data and conceptual content, based on five concepts of the therapeutic relationship, namely empathetic understanding, positive regard, genuineness, concreteness and self-exploration (see Table 1 for the format of the questioning).

Genuineness as one of the concepts of a therapeutic relationship (Rogers, 1957, p. 100) was operationalised in the questionnaire in the form of a scenario (see Table 1). Participants were invited to rate how they perceived each of the five nurse-facilitated responses to the patient in the scenario on a scale ranging from "not at all" to "to a large extent".

Responding "to a large extent" (5) on the higher levels (three, four and five) as seen in the scenario means that the participants perceived the responses which facilitate genuineness in the nurse-patient relationship to a large extent. The reverse is true for the lower levels; when the negative responses on the lower levels (one and two), as described in the scenario, were "to a large extent" (5) the participants perceived facilitation of insincere and destructive responses to a large extent.

The questionnaire took 20-30 min to complete, and participants were asked to place the completed questionnaires in a sealed box to be collected after 2 h by the researcher. No personal identification was required; questionnaires were coded for statistical purposes.

8. Ethical considerations

Once ethical approval and permission from the university and the private hospital authorities were obtained (AEC24/01-2011), the procedure was explained and the participants were given the opportunity to read the covering letter and agree to voluntary participation. In accordance with ethical measures (Dhai & McQuoid-Mason, 2011, p. 14) participants were assured of anonymity, confidentiality, beneficence and non-maleficence.

9. Validity and reliability

Content validity was based on the extent to which the questions in the questionnaire and the scores obtained from the participants were representative of the possible questions that a researcher could ask about the content or concepts being measured (Creswell, 2008, p. 172). The questions were based on theory and formulated in the light of existing literature. A pilot study was conducted among nurses working in another hospital of the same private healthcare group to test the practicability of the research instrument. Content validity was further enhanced by experienced specialists in the fields of nursing and educational research who examined the questionnaire (Botes, 2005, p. 191).

Internal consistency was assessed with Chronbach's alpha coefficient (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 731). Reliability was reasoned to be acceptable, considering that each one of the scenarios explored a different concept of the therapeutic relationship.

10. Data analysis

In the original study, a total of 240 questionnaires were distributed and 184 were returned and used for analysis. Data was analysed using statistical software SPSS-18. A variety of statistical analyses were applied to the data, including Kol-mogorov-Smirnov, Student t-test, Mann-Whitney U and Kruskall-Wallis non-parametric tests. Characteristics of nurses and groups of nurses were described while inferential statistics were utilised to test hypotheses on comparing groups and make deductions from the data (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 408).

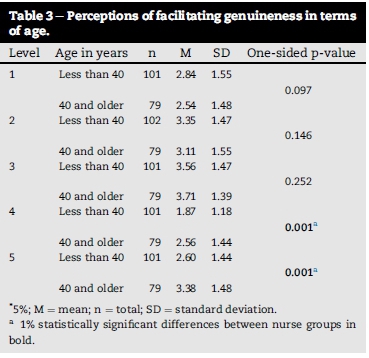

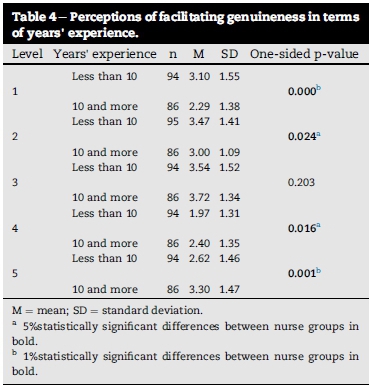

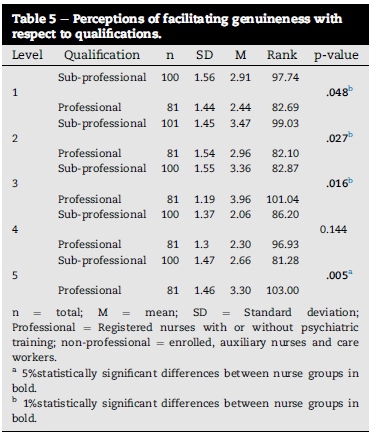

A general hypothesis was tested, based on the expectation that variables of age, experience or qualifications might play a role in their perception of facilitating genuineness. The specific hypotheses that were tested precede each table (Tables 3-5). In the case of the Student's t-test, one-sided testing was done. The reason for this is that research and experience support the creation of such expectations where statistical values of interest are thought to occur in a single tail of the curve (Burns, Grove, & Gray, 2013, p. 545). The null hypothesis (Ho) was rejected on the 5% level of significance (p-value was less than 0.05) or on the 1% level of significance (p-value less than 0.01).

11. Research findings

The information from 184 questionnaires was used for descriptive analysis and to describe the following biographical data of the total sample in the original study: 33.7% (n = 62) were registered nurses (RN) and 10.9% (n = 20) were registered nurses with a psychiatric qualification. Other categories consisted of 21.7% (n = 40) enrolled nurses (EN), 17.4% (n = 32) enrolled auxiliary nurses (ENA), and 16.3% (n = 30) care workers (CW).

For statistical purposes groups were allocated according to the descriptive analysis of the biographical data obtained: 56.3% were younger than 40 years of age (n = 101) and 43.7% were older than 40 years (n = 79); mean age was 38.58 years; 52.7% had less than 10 years' experience (n = 96), and 47.3% had more than 10 years' experience (n = 87), thus there was a mean of 9 years' experience. Nursing qualifications were further collapsed into two groups: a) professional group -registered nurses with or without psychiatric qualifications (44.4%, n = 82); and b) sub-professional group (55.6%, n = 102) consisting of enrolled and auxiliary nurses and care workers.

Of the 184 in the sample, only 181 participants marked the responses of the particular scenario which assessed perceptions of facilitating genuineness. Data presented in this article applies to the 181 participants (see Tables 1-5).

In terms of the total responses (Table 2) on the higher levels (four and five), only 29.3% of all participants perceived facilitating of genuine responses "to a large extent". The reverse is true for the lower levels; the total negative or destructive responses on the lower levels (one and two), were marked to "a large extent" by 47.3% of the participants, while hope on level three, was advocated by 39.2% of all participants (Table 2).

12. Differences in perceptions of facilitating genuineness between nurse groups

Perceptions of various categories of nurses were compared and specific hypotheses were tested with non-parametric statistical techniques (Tables 3-5).

General null hypothesis (H0): There is no statistically significant difference between specific groups: age groups (Table 3), years of experience (Table 4), and professional status (Table 5) of nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship.

Each of the alternative hypotheses stated with Table 3 (Ha1), 4 (Ha2) and 5 (Ha3) will now be discussed in the following section.

Ha1: The mean of the one group of nurses' (younger) perceptions of facilitating genuineness is statistically significantly lower than the second group of nurses (older) when tested with the Student's t-test (see Table 3).

From Table 3 it is clear that H01 is rejected in favour of Ha1 on the 1% level of significance for levels four (4) and five (5). This supports the expectation that nurses 40 years and older, when compared to nurses younger than 40 years, are more aware of genuine responses according to their perceptions.

Ha2: The mean of the one group of nurses' perception of facilitating genuineness is statistically significantly lower than the mean of the second group of nurses when tested with the Student's t-test (see Table 4).

From Table 4 it is clear that by applying the post hoc onesided Student's t-test, an interesting finding is observed. In the case of levels 1 and 2, the group of nurses with less than 10 years' experience as a nurse had significantly higher means than the group with more experience (level 1: 3.10 versus 2.29 on the 1%-level; level 2:3.47 versus 3.00 on the 5%-level). In the case of levels 4 and 5 the means of the group of nurses with less than 10 years' experience were statistically significantly lower when compared to the group of nurses with 10 years or more experience (level 4: 1.97 versus 2.40 on the 5%-level; level 5: 2.62 versus 3.30 on the 1%-level). In the case of level 3, there is no statistically significant difference and H0 is not rejected.

This observation indicates that on levels 1 and 2, nurses with less than 10 years' experience perceive genuineness to be either negative and destructive or as false reassurance. This is in contrast to the finding that on levels 4 and 5, nurses with more experience perceive the responses to be non-destructive and more reflective of genuineness when compared with those with less experience as a nurse. This finding is, however, in accordance with the expectations that on higher levels of reflections the senior (older) and more experienced group of nurses are more thoughtful and most probably more genuine towards their response to patients. On the lower levels the junior (younger) group of nurses might be more task-orientated and less reflective. However, literature with regard to nurses' genuineness is scarce and further research as to the real reason for this finding needs to be conducted.

Specific alternative hypothesis (Ha3): There is a statistically significant difference between specific groups of nurses' rank orders of how facilitating genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship is perceived with respect to qualifications, tested with the Mann-Whitney U test: rank order (see Table 5).

A post-hoc inspection of the rank order analysis indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in rank orders on levels 1, 2, 3 and 5. From Table 5 it is clear that H03is rejected in favour of Ha3 on the 5% level of significance for levels one (1), two (2) and three (3), and on the 1% level of significance for level five (5). It could be reasoned that nurses' perceptions of facilitating genuineness have been affected by training and development.

In summary, when groups were compared, the alternative hypotheses were supported on various levels of facilitation (Tables 3-5). Ha1 indicates that the first group of nurses' perceptions (younger than 40 years) show statistically significantly less facilitation of genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship when compared to the second group (40 years and older). Ha2 indicates that the group of nurses with 10 years and more experience as a nurse perceive genuineness to be reflective and non-destructive. Ha3 indicates that there is a difference in rank order between the professional groups when compared to the sub-professional group tested with the Mann-Whitney U test.

Finally, mean scores observed in Tables 3 and 4 reflect an average of 3 on most levels of facilitating genuineness; the lowest is 1.87 and the highest is 3.72. Although significant, most of the differences observed are small, but nevertheless important for nursing practice.

13. Discussion of the results

While genuineness and honesty is closely linked, it can be deduced that the responses on the lower levels reflect that nurses seem to avoid telling the truth, rather than to allow genuineness within a caring and trusting relationship. In the case of valuing honesty, it is recommended that truth telling should depend on what the patient wants to or is prepared to know; at the very least, nurses should not impose their own preferences on the patient (Tse et al., 2003, p. 2).

Asking patients what they or their family think is not only mindful of patients' autonomy in decision making, but also reflects an openness and genuineness about not knowing everything. According to Tuckett (2004, p. 500), one ought to ask patients and their families what information they require, and to explore the cultural nature of the patient. In a two decade replication study done by Johnson et al. (2007, p. 373), it was found that in comparison with earlier studies, nurses were less inclined to lie to patients in 2005. Being truthful is ethical, and honest disclosure of medical information gives patients a sense of control and actually increases their hopefulness (Beste, 2005, p. 230).

Hope on the other hand, implies a degree of uncertainty (Little & Sayers, 2004, p. 1335), and how hope is conceptualised determines whether it is perceived as false hope (Miller, 2007, p. 18). A large percentage (39%) of all the participants perceived facilitation of hopefulness as a genuine response. Although genuineness seems to be related to hope which is verbalised on level 3 of the scenario (Tables 1 and 2), the response mayseem vague and neither insincere nor facilitative of genuineness. It is reasonable to say then, that most nurses' perceptions of hope are to a greater extent supported by virtue terms (Begley, 2008, p. 341). Nurses' roles are mainly seen as helping people to get better, and therefore, in some circumstances withholding the truth to protect hope can be considered a morally acceptable option and a construct central to nursing (Miller, 2007, p. 12; Begley & Blackwood, 2000, p. 30).

The older, more experienced and professional nurses' perceptions could therefore be motivated by compassion, grounded in their professional judgement and guided by practical and theoretical wisdom gained from experience and from reflection of being truly "genuine" towards patients and their families. Of importance is that these groups of nurses also seem to have gained from the process of developing skills and attitudes through socialisation and experiential learning (Scanlon, 2006, p. 328). This may indicate that experience plays a role in the development of greater genuineness. Nurses continuously need to reflect and draw insight gained from experience (Begley, 2008, p. 338; Scanlon, 2006, p. 328), while current experiences in the here and now should be used to enhance mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 823). Without mindfulness, reflection and self-awareness nurses could get muddled with thinking and their own feelings, and miss out on an important part of genuineness in the therapeutic relationship (Wells, 2000, p. 75).

It could be deduced that knowledge and skills play a vital role in facilitating genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship and can be acquired through learning and teaching (Pickens, 2005, chap. 3, p. 11), hence the difference in perceptions of professional and sub-professional nurses. Within the framework of traditional or bio-medical views, nurses are able to use acquired knowledge in patient-care, but often fail to acknowledge the patients' explanations with regard to their mental health problems or experiences (Walsh, Stevenson, Cutcliffe, & Sinck, 2008, p. 251). Understanding and managing patients who are vulnerable or anxious demands a higher level of resilience and expertise (Hanrahan & Aiken, 2008, p. 5). Studies have found that higher education mitigates poor patient outcomes among vulnerable patients (Kutney-Lee & Aiken, 2008, p. 1) who are also more sensitive to a trusting relationship. The authors of this article agree with Torres-Rivera et al. (2006, pp. 2-5) that the focus of most training courses seems to remain professionally orientated, with little attention given to personal relationships, self-reflection and internal states of self-awareness which are the cornerstones of genuineness in a nurse-patient relationship.

Carl Rogers (1957) theorised that by being genuine and deeply involved, a person is not "acting" and can draw on experiences and awareness to facilitate a relationship. In agreement with Poggenpoel (1997, p. 29), the findings of this study show that as a result of the nurses' perceptions of their own genuineness most of them still tend to reassure, moralise or give advice from within their own frame of reference. In a nurse-patient relationship, each person's perception of the other is important. However, what nurses perceive is their own reality and not necessarily the truth. To avoid uncertainty, nurses may hide their ignorance, or rather be influenced by their own values or a prescribed role of what is perceived in a certain situation.

14. Challenges of the research

As seen in the literature, culture and beliefs play an important role in a person's attitude and how perceptions are formed. The influence of culture on facilitation of genuineness was not explored in this study despite the ethnic diversity of staff and patients in private general hospitals in Gauteng. Nurses from only three private general hospitals participated in the research, and the results can thus not be generalised to other private and provincial hospitals. Care workers have limited clinical nursing functions, but are employed by private hospitals to work alongside nurses in close relationship with patients, hence their inclusion in the sub-professional group.

15. Recommendations

The statistically significant differences, however small, between the nurse groups are of value for training and practice:

Older, professional and experienced nurses are more reflective and mindful with regard to the facilitation of genuine responses and their skills should be applied to mentor younger, inexperienced and less qualified nurses.

Employers should be aware that younger, inexperienced and unqualified nurses are at risk of insensitive and inappropriate facilitation of nurse-patient relationships, which could affect patient outcomes and quality of care.

There is a need for reflective mindfulness interventions to provide nurses with insight into their own vulnerabilities, values and expectations of genuineness. Because of the higher-level skills related to communication and decision making, private general hospitals should incorporate scenario-based, experiential training and simulation into their training courses.

Realistic scenarios could provide meaningful learning opportunities for both new and experienced nurses to apply theoretical knowledge and to experience respect and values, and to also have fun in a controlled environment without risk to the patient (Nagle et al. 2009, p. 23).

In the light of the cultural diversity of patients and nursing staff in South Africa and also worldwide, further research into the cultural effects on the facilitation of genuineness is suggested.

16. Conclusion

The findings highlight the importance of genuineness as a core component of the nurse-patient relationship. Although the professional, older and experienced group of nurses' views are encouraging, everything possible should be done to promote nurses' understanding of genuineness, virtue ethics, and mindfulness. Hope is central to life and specifically when dealing with illness, but what is worrying is that nurses are not always aware of the extent to which their responses could be experienced as helpful, hopeful, false or superficial and mindless.

REFERENCES

Aiken, A., & Aiken, J. L. (May 1973). A systematic approach to the evaluation of interpersonal relationships. American Journal of Nursing, 73(5), 863-867. [ Links ]

Arnold, E. C., & Boggs, K. U. (2011). Interpersonal relationships; professional communication skills for nurses (6th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & Son, C. (2000). Honesty as the sixth factor of personality: correlations with Machiavellianism, primary psychopathy, and social adroitness. European Journal of Personality, 14(4), 359-368. http://www.ingentaconnect.com. July/Aug 2000 Online ISSN: 1099-0984. [ Links ]

Begley, A. M. (2008). Truth-telling, honesty and compassion: a virtue-based exploration of a dilemma in practice. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 14, 336-341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.00706.x. [ Links ]

Begley, A. M., & Blackwood, B. (2000). Truth-telling versus hope: a dilemma in practice. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 6, 26-31. [ Links ]

Beste, J. (2005). Instilling of hope and respecting patient autonomy: reconciling apparently conflicting duties, 0269-9702 (print), 1467-8519 (online) Bioethics, 19(3) Accessed 03.01.14. [ Links ]

Botes, A. (2005). Validity, reliability and trustworthiness. In D. Rossouw (Ed.), Intellectual tools; skills for human sciences (pp. 190-196). Pretoria: Amabhuku publications. [ Links ]

Bozarth, J. D. (2001). Forty years ofdialogue with the rogerian Hypothesis. http://personcentered.com/dialogue.htm Accessed 3.05.11. [ Links ]

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). Benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822-848. [ Links ]

Burns, N., Grove, S. K., & Gray, J. R. (2013). The practice ofnursing research; appraisal, synthesis, and generation ofEvidence (7th ed.). USA: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Carkhuff, R. R. (1969). Helping and human relations. In Practice and research (Vol. 11, pp. 319-320). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research, planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Dhai, A., & McQuoid-Mason, D. (2011). Bioethics, human rights and health law: Principles and practice (pp. 14-15). Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Epstein, R. M., & Street, R. L., Jr. (2007). Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute (NIH - Publication NO 07-6225). Bethesda, U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Available from http://outcomes.gov/areas/pcc/communication/pccm_flyer.pdf Accessed 20.01.12. [ Links ]

Frisch, N. C., & Frisch, L. E. (2011). Psychiatric mental health nursing (4th ed.). USA: Delmar. [ Links ]

Gilbert, S. (Oct 2009). Psychiatric crash cart: treatment strategies for the emergency department. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 31(4), 298-308. Available from http://www.nursingcenter.com/library/JournalArticle.asp?Article_ID=942591 Accessed 10.02.12. [ Links ]

Hanrahan, N. P., & Aiken, L. H. (2008). Psychiatric nurse reports on the quality of psychiatric care in general hospitals. Quality managed healthcare, 17(3), 210-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.QMH.0000326725.55460.af. [ Links ]

Johnson, M., Haigh, C., & Yates-Bolton, N. (2007). Valuing of altruism and honesty in nursing students: a two-decade replication study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(4), 366-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04119.x. [ Links ]

Kutney-Lee, A., & Aiken, L. H. (December 2008). Effect of nurse staffing and education on the outcomes of surgical patients with co-morbid serious mental illness. Published in final edited form as Psychiatric Services, 59(12), 1466-1469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/APPI.PS.59.12.1466. [ Links ]

LaSala, C. (December 2009). Moral accountability and integrity in nursing practice. Nursing Clinics of North America, 44(4), 423-434. [ Links ]

Little, M., & Sayers, E. (2004). While there's life ... hope and the experience of cancer. Social Science & Medicine, 59(6), 1329-1337 Accessed 2.01.14. [ Links ]

Menzies-Lyth, I. (1988). Containing anxiety in institutions: Selected essays (Vol. 1). London: Free Association Books LTD. [ Links ]

Miller, J. F. (January-March, 2007). Hope: a construct central to nursing. Nursing Forum, 42(1), 12-19. [ Links ]

Moyle, W. (2003). Nurse-patient relationship: a dichotomy of expectations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12, 103-109. [ Links ]

Nagle, B. M., McHale, J. M., Alexander, G. A., & French, B. M. (2009). Incorporating scenario-based simulation into a hospital nursing education program. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 40(1), 18-25 Accessed 14.02.14. [ Links ]

Pickens, J. (2005) (Chapter 3). In N. Borkowski (Ed.), Attitudes and perceptions: Organizational behaviour in health care. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett publishers. [ Links ]

Poggenpoel, M. (1997). Nurses' responses to patients' communication. Curationis, 20(3), 26-32. [ Links ]

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Reed, F., & Fitzgerald, L. (2005). The mixed attitudes of nurses to caring for people with mental illness in a rural general hospital. International Journal ofMental Health Nursing, 14, 249-257. Available from http://0web.ebscohost.com.ujlink.uj.ac.za/ehost/results?vid=pdf Accessed 10 06 09. [ Links ]

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal ofConsulting Psychology, 21,95-103. [ Links ]

Scanlon, A. (2006). Psychiatric nurses perceptions of the constituents of a therapeutic relationship: a grounded study. Journal ofPsychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13, 319-329. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Smith, K. V., & Godfrey, N. S. (2002). Being a good nurse and doing the right thing: a qualitative study. Nursing Ethics, 9(3), 300-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0969733002ne512oa (301). [ Links ]

Torres-Rivera, E. T., Phan, L. T., Maddux, C. D., Wilbur, J. R., & Arredondo, P. (2006). Honesty and multicultural counselling. Interamerican Journal ofPsychology,2-5. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S0034-969020060001000047&script=sci_artt Accessed 05 07 13. [ Links ]

Tse, C. Y., Chong, A., & Fok, S. Y. (2003 Jun). Breaking bad news: a chinese perspective. Palliative Medicine, 17(4), 339-343. PMID: 12822851 PubMed http://www.ncib.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12822851 Accessed 26.07.13. [ Links ]

Tuckett, A. G. (2004). Truth-telling in clinical practice and the arguments for and against: a review of the literature. Nursing Ethics, 11(5), 500-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0969733004ne728oa Accessed 26.07.13. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, G. (January-June 2010). A discourse and content analysis of how nursing is framed in the mainstream press in South Africa. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Van den Heever, A. E. (2012). Nurses' own perception of their therapeutic relationship in providing care to patients with mental health disorders. Unpublished Masters dissertation. University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Van den Heever, A. E., Poggenpoel, M., & Myburgh, C. P. H. (2013). Nurses and care workers' perceptions of their nurse-patient therapeutic relationship in private general hospitals, Gauteng, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 18(1), 7. Art. #727 http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.727 Accessed 04.1.2013. [ Links ]

Vythilingum, B. (October 2009). Anxiety disorders in pregnancy and the postnatal period. Continuing medical education (CME), 27(10), 450-452. Available from http://www.ajol.info/index.php/cne/article/viewFile/50326/39013 Accessed 24.03.11. [ Links ]

Walsh, J., Stevenson, C., Cutcliffe, J., & Zinck, K. (7 August 2008). Creating a space for recovery-focused psychiatric nursing care. Nursing Inquiry, 15, 251-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00422.x Accessed 26.07.13. [ Links ]

Wells, D. (Ed.). (2000). Caring for sexuality in health and illness. London: Churchill Livingstone. [ Links ]

Received 23 February 2015

Accepted 26 February 2015

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +27 (0) 11 488 4061; +27 (0) 83 258 9953 (mobile).

E-mail address: Annalie.vandenheever@wits.ac.za (A.E. Van den Heever).