Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.20 no.1 Cape Town 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.HSAG.2015.03.001

The health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS

Judy ThompsonI, *; Yolanda HavengaI, II1; Susan NaudeI, III2

IUniversity of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus), PO Box 142, Medunsa, 0204, South Africa

IITshwane University of Technology, South Africa

IIIHealth Systems Trust, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Women in Sub-Saharan Africa are disproportionately affected by the virus and constitute 60% of the total HIV/AIDS infections in this region. Current recommendations endorse the involvement of people living with HIV in the development of programmes for people living with the virus. The purpose of the study was to explore and describe the health literacy needs of women living with HIV. The research design was qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual. After women living with HIV/AIDS were sampled purposively, semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight women and qualitative content analysis done. The findings revealed that the women expressed a need to increase their knowledge about HIV/AIDS. The knowledge they needed ranged from basic pathophysi-ology about HIV/AIDS, to the impact of HIV/AIDS on their health, to an awareness of the modes of HIV transmission and methods of protecting others from being infected. Other important health literacy needs related to self-care and correct antiretroviral use. A need for psychosocial skills was also identified in order for women to build and maintain their relationships. Recommendations were made for nursing practice, education and further research, based on these findings.

Keywords: Health literacy, Women, HIV/AIDS, Needs

ABSTRAK

Vroue in Sub-Sahara-Afrika word buite verhouding geraak deur die virus en vorm 60% van die totale MIV/VIGS - infeksies in hierdie streek. Huidige aanbevelings onderskryf die betrokkenheid van mense met MIV/VIGS in die ontwikkeling van MIV/VIGS programme vir mense met die siekte. Die doel van hierdie studie was om die gesondheid geletterdheid behoeftes van vroue met MIV te verken en te beskryf. Die navorsing was kwalitatief, verkennend, beskrywend en kontekstueel. Vroue met MIV/VIGS is doelgerig geidentifiseer en semi-gestruktureerde onderhoude is met agt vroue gevoer waarna kwalitatiewe inhoud-sanalise gedoen is. Die bevindinge het getoon dat die vroue 'n behoefte het om hul kennis oor MIV/VIGS uit te brei. Die kennis wat hulle benodig wissel van basiese patofisiologie oor MIV/VIGS, die impak van MIV/VIGS op hul gesondheid, 'n bewustheid van MIV-oordrag en maniere om naasbestaandes teen besmetting te beskerm. Ander belangrike gesondheid geletterdheid behoeftes het betrekking tot self-sorg en korrekte antiretrovirale gebruik. 'n Behoefte aan psigososiale vaardighede is ook gei'dentifiseer sodat vroue verhoudinge kan behou en bou. Aanbevelings gebaseer op hierdie bevindinge is vir die verpleegpraktyk, verpleegonderwys en verdere navorsing gemaak.

1. Introduction

Women can play a key role in the response to HIV/AIDS; in sub-Saharan Africa, they are disproportionately infected and affected by HIV/AIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 66). Women play a pivotal role in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission and are, more often than men, the caregivers for those living with HIV/ AIDS (Erhardt, Sawires, McGovern, Peacock, & Weston, 2009, p. 99). It is therefore crucial that women be involved in the response to HIV/AIDS as has been pointed out: "When women speak out, we must listen carefully, and act with solidarity and commitment to transform words into action" (Bachelet, GatdiMallet, & Sidebe, 2012, p. 6). This article gives voice to a small group of women living with HIV/AIDS on the health literacy needs they see as necessary for themselves and others living with HIV/AIDS to know.

1.1. Background

Globally, for women of reproductive age, HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2009. p. 27). Worldwide almost half (49%) of all people living with HIV are women (UNAIDS., 2012b, p. 10). In sub-Saharan Africa, however, women constitute nearly 60% of all people living with HIV (UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 66). In the case of young women (between the ages of 15 and 24 years) in sub-Saharan Africa, 3.1% are living with HIV versus 1.3% of young men (UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 89). Of all HIV-positive pregnant women, 92% live in sub-Saharan Africa (UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 41). These statistics point to the disproportionate HIV infection of women (especially young women) in sub-Saharan Africa, which is a serious concern for women's health and the health of their children (UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 41), families, and the community.

This disproportionate infection of women is due to gender inequality and women's physiological vulnerability during sexual intercourse (UNAIDS & WHO, 2009, p. 21). In addition to their vulnerability to HIV infection, women bear the greatest proportion of caregiver responsibilities for people living with HIV/AIDS due to their traditional roles of caring for sick family members and making health-related decisions for their families (Erhardt et al., 2009, p. 99). In spite of the significant impact that HIV/AIDS has on the female population, UNAIDS. (2012a, p. 14) reports gaps in young women's basic knowledge of HIV and its transmission. The organisation reports that in their multi-country study, in 26 of the 31 countries that participated in the national surveys, fewer than 50% of young women had complete and accurate knowledge about HIV.

Health education plays an important role in expanding knowledge, but research shows that a variety of skills and competencies are necessary to understand and utilise health knowledge (Zarcadoolas, Pleasant, & Greer, 2005, p. 196). These skills and competencies include reading and understanding medication labels, calculating medication intervals, and following basic self-care instructions, all of which combine to indicate health literacy.

Health literacy refers to the ability to read health-related material, obtaining and applying information related to health matters (Finset & Lie, 2010, p. 1), and facilitating health and health-related decision-making processes (Baker, 2006,p. 881). Zarcadoolas et al. (2005, p. 197) explain that health literacy is dependent on fundamental literacy aspects such as reading, speaking, writing and interpretation, but it also relies on an awareness of current developments in health, science and public issues. The customs and beliefs of an individual, which influence their ability to interpret and act on health information, are also considered instrumental in health literacy (Zarcadoolas et al., 2005, p. 197).

Competent healthcare providers and health information based on an assessment of the client's needs improve health literacy and the autonomy of the client. Autonomy is reflected in the development of knowledge and skills that allow independent decision-making in healthcare (Zarcadoolas et al., 2005, p. 196). This autonomy is especially vital for women living with HIV/AIDS to improve their health outcomes and consequently the health outcomes of their families and the larger community.

1.2. Problem statement

The 2009 AIDS Epidemic Update recommends the involvement of people living with HIV in the development of HIV-related programmes (UNAIDS & WHO, 2009, p. 9). Despite the pivotal role of women in addressing the HIV pandemic, women living with HIV/AIDS have not been fully involved as leaders in designing and implementing HIV prevention programmes (UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 15).

The health education and literacy needs of healthcare workers and caregivers working with people living with HIV/ AIDS have been described (Maneesriwongul et al., 2004), but few studies involve people living with HIV/AIDS in describing their own health literacy needs. A study by Nokes, Kendrew, Rappaport, Jordan and Rivera in 1997 assessed the learning needs of HIV-positive persons regarding issues relevant to living with HIV/AIDS. The participants were predominantly male. A study that investigates the health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS is therefore proposed.

A collaborative initiative by universities and health services to investigate the empowerment of women identified a semi-rural setting in Gauteng and encouraged projects to explore and promote female empowerment in this setting. The site hosts a wellness clinic that focuses on patients living with HIV/AIDS. High HIV infection rates among South African women combined with the low literacy levels of the community in this particular setting (Plan Associates, 2005,p.6) provided the researcher with an opportunity to identify the knowledge and skills required by women to enhance their health literacy and promote autonomous health-related decision making. Information about these women's health literacy needs would enable healthcare providers to provide relevant health education. In order to address the research problem the following research question was formulated:

What are the health literacy needs of women living with HIV attending a specific wellness clinic in Gauteng?

1.3. Purpose and objective of the study

The purpose of the study was to identify the health literacy needs pertaining to the knowledge and skills required by women living with HIV/AIDS to enhance their health literacy and promote autonomous health-related decision-making. By investigating these health literacy needs, recommendations can be made for healthcare providers to address these needs. The objective of the study was to explore and describe the health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS attending a specific wellness clinic in Gauteng.

1.4. Delimitation of the study

Health literacy entails more than knowledge and information, it includes skills to apply knowledge and considers perceptions and cultures that might influence the way health information is perceived, interpreted and applied. Health literacy is also dependent on literacy and numeracy proficiency and social awareness, and ultimately leads to autonomy in healthcare decision making.

This study serves as an introduction to health literacy needs with the emphasis in this article on identifying the knowledge and skills required by women living with HIV/ AIDS. The study did not investigate values, beliefs and culture as aspects of health literacy.

1.5. Definition of key concepts

1.5.1. Health literacy needs

Health literacy is the extent to which a person is able to find, process, and understand health-related information and the services necessary to make suitable health decisions (Institute of Medicine, cited in Paasche-Orlow and Wolf (2007, p. 21). For the purpose of the current study, a need is defined as the lack of something required, wanted or necessary (Farlex, 2013). In this context the term health literacy needs thus refers to the knowledge and skills necessary for women living with HIV/ AIDS to enable them to find, process and understand HIV-related information and services needed to make appropriate health-related decisions.

1.5.2. Women living with HIV/AIDS

For the purpose of this study, this concept refers to women 18 years and older who presented with a positive HIV antibody test (WHO, 2007, p. 8) or who met the clinical criteria for diagnosis of advanced HIV according to national policies and guidelines (WHO, 2007, p. 8) and who attended the wellness clinic at a specific hospital in Tshwane.

1.5.3. Wellness clinic

For the purpose of this study, wellness clinic refers to the site at a hospital in Gauteng where women living with HIV/AIDS were seen and antiretroviral therapy was administered in accordance with South African protocols and guidelines.

2. Research design and method

2.1. Design and context

A qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual design was selected in order to develop an in-depth understanding of the health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS (Creswell, 2009, p. 178; Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 505).

The wellness clinic where the study was conducted provides services to persons living with HIV/AIDS. The wellness clinic serves a population that is predominantly Setswana speaking, living in both fixed houses and informal dwellings, with water, sanitation and electricity mostly available (Plan Associates, 2005,p.4& 6). About half of the population is unemployed and formal education is limited with just over half of the population having a primary school qualification or less (Plan Associates, 2005, p. 6). The participants regularly attended this particular wellness clinic for their follow-up care and treatment. The study is therefore considered contextual (Creswell, 2009, p. 175).

2.2. Population and sampling

The population included all HIV-positive women who attended a wellness clinic where antiretroviral treatment (ART) is provided. The participants were purposively sampled (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 517) based on the following inclusion criteria: females (18 years and older), HIV-positive and at least half of the sample had to be on ART to provide insight into treatment-related issues. Participants who were able to speak either Setswana or English were included. Women who were mentally or physically unable to participate in an interview due to their level of illness were excluded in the interest of doing no harm. The sample comprised eight women and saturation of data was achieved as evidenced by the repetition of themes (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 521).

2.3. Data collection

Data was collected between July 2010 and August 2010 by means of semi-structured individual interviews (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 537) which assisted the researcher in gaining an in-depth understanding of the health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS. All interviews were conducted separately in a private room at the ART facility while participants were awaiting consultation. Interviews were audio-recorded and, on average, lasted 45 min each. Participants were interviewed in English or Setswana according to their proficiency and preference. The interviewer was proficient in English, but participants were given the opportunity to be interviewed in Setswana if they agreed to a translator being present. The translator was proficient in a number of South African languages. Five interviews were conducted in English, two in Setswana and another in a mixture of both languages.

A semi-structured interview schedule was compiled based on the work of Nokes, Kendrew, Rappaport, Jordan, and Rivera (1997, p. 49) who developed the HIV Educational Needs Assessment Tool (HENAT) which examines the education needs under specific headings, namely: treatments, entitlements, relationships, preventing infections, social support and working. Thirteen open-ended questions were developed based on the learning needs listed in the HENAT (Nokes et al., 1997, p. 49) to assist the participants in the exploration of HIV information needs (see the operational definition for health literacy) related to various aspects of living with HIV/AIDS (Table 1).

Three non-directive questions were asked with regard to the perceived health literacy needs of women living with HIV/ AIDS, after which ten open-ended questions facilitated further exploration of specific topics that were identified from the work of Nokes et al. (1997). As residents in the area were predominantly Setswana speaking (Plan Associates, 2005,p.4) the questions were also translated from English into Set-swana. The interview schedule was piloted, after which questions were rephrased for clarification and reorganised into a more logical and flowing sequence.

Observational and reflective field notes (Polit & Beck, 2012, pp. 548-549) allowed for observations about the participants' tone of voice and behaviour during interviews, as well as for reflection on the data as it was collected.

2.4. Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and were analysed using qualitative content analysis (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 564). Interviews in Setswana were also transcribed verbatim and translated into English by a person fluent in both Setswana and English, and were checked by a second person capable of speaking both languages. The analysis involved reading all eight transcripts to obtain a general idea of the content. The interviews were analysed individually to identify emerging themes. The data was reviewed continuously to find meaning in phrases and to understand the health literacy needs of the women until clear themes could be identified and all data was assigned to themes (Creswell, 2009, p. 185). An independent coder undertook a separate data analysis for the purpose of doing an inter-coder check with the researcher (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 588). The researcher and independent coder reached consensus on the themes identified.

3. Ethical considerations

Women living with HIV/AIDS are a particularly vulnerable population, both due to gender-based inequality and the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS. It was therefore important that the researcher ensured that the rights of this vulnerable population were protected (Polit & Beck, 2012, pp. 152-156). The following measures were taken to ensure the protection of the participants.

The study was approved by the University of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus) and the regional health authority's research ethics committees before commencement of the research. The relevant authorities at the wellness clinic also approved the research. Although there was no foreseeable physical harm, there was the potential for emotional discomfort when participants were relating their personal stories associated with living with HIV/AIDS. To mitigate this discomfort, the researcher conducted these interviews with a non-judgemental and accepting attitude. Provision was made for support by a psychiatric nurse or referral for counselling if participants felt upset. Referral was not required for any of the participants. The researcher was not a regular nurse in the wellness clinic, therefore the potential for exploiting the participating women in the clinic where they accessed healthcare and treatment was minimised.

Full disclosure and the right to self-determination (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 154) were ensured by providing participants with comprehensive information, verbally and in writing, in their mother tongue, about the study and the audio-recordings before they volunteered their participation and completed written informed consent forms. They were also informed that they could refuse to participate or could withdraw from the study at any time without compromising their healthcare programme.

The right to privacy (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 156) was ensured by removing all names from transcripts, and not connecting or storing the informed consent forms with the transcripts or biographical information of the participants. Biographical information was limited to ensure anonymity, confidentiality and privacy. Only questions relevant to the research were asked and participants were informed that they had the right to choose whether to respond to all the questions. Recruitment of participants was done at a facility where all attending patients were HIV-positive, and therefore there was no risk of involuntary HIV status disclosure; interviews were conducted privately and the identities of the participants were kept confidential. Data will be stored in a secure location for five years in a digital password-protected format.

The right to fair treatment (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 155) was ensured by honouring all agreements made with the participants, not disadvantaging participants who did not want to participate, and not including participants who were physically or mentally too ill to participate at the time. Participants were selected based on the inclusion criteria of the study and not based on their vulnerabilities as healthcare users accessing services in the specific wellness clinic.

4. Trustworthiness

Lincoln and Guba's framework (as cited in Polit & Beck, 2012, pp. 583-595) was applied throughout the research process to enhance trustworthiness, based on the five criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability and authenticity. As a professional nurse with experience in working with people living with HIV/AIDS and interviewing skills, the researcher was able to ensure accurate data collection and contribute to the credibility of the study (Krefting, 1991, p. 220). In addition, the researcher enhanced data collection triangulation by interviewing eight participants, some on ARVs and others not. The dependability of data was enhanced through well-kept documentation and transparency in the methodology, data analysis and conclusions. In order to enhance confirmability of the study, peer debriefing, data triangulation, reflection and bracketing of preconceived ideas and views enhanced the accurate collection and interpretation of data (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 588). Transferability was enhanced through interviewing until saturation was confirmed by an independent coder and by providing detailed descriptions of the research methods and findings, and taking field notes (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 588). Audio-recordings of the interviews enhanced the authenticity and were supplemented by including verbatim quotes from women in the description of the findings (Polit & Beck, 2012, p. 588).

5. Findings

The findings reflect the health literacy needs of eight women ranging from 21 to 45 years of age who were living with HIV/ AIDS. Three of the women in the sample were unemployed, two had no education and three had completed grade 12 and post-school courses. One participant had taken a course in HIV/AIDS counselling. The other three participants completed grades 7, 9, and 10 respectively. Of the eight participants six were on anti-retroviral treatment.

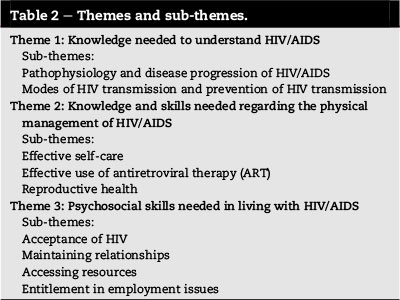

Three themes of health literacy needs were identified: "knowledge needed to understand HIV/AIDS", "knowledge and skills needed regarding the physical management of HIV/ AIDS" and "psychosocial skills needed in living with HIV/ AIDS". Each theme was founded on a number of sub-themes (Table 2).

Theme 1. Knowledge needed to understand HIV/AIDS

The first theme is related to basic knowledge about HIV/ AIDS and forms the departure point for health literacy in living with HIV/AIDS. Each sub-theme represents specific aspects that are necessary for women to understand HIV/AIDS.

5.1. Suh-theme: pathophysiology and disease progression of HIV/AIDS

The women described the need to be more knowledgeable about the pathophysiology and disease progression of HIV/ AIDS in order to understand the disease better. The general consensus was that knowledge about the CD4 count and viral load, as well as their interrelatedness, would improve the women's understanding of HIV/AIDS:

"It's a virus and then not knowing how it infects you and when you are infected, how must you keep yourself you know, healthy, living longer. I think what will encourage people is when people know that HIV doesn't kill. I think that will be more [very]3 helpful to people."

Understanding HIV and its progression naturally leads to questions about the spread of the virus, which emerged as the second sub-theme in knowledge about HIV/AIDS.

5.2. Suh-theme: modes of HIV transmission and prevention of HIV transmission

The data showed that women needed to know about the transmission of HIV to understand which actions put themselves and others at risk of infection. They explained that this knowledge would not only help them to protect their partners and loved ones, but would also prevent the transmission of HIV from mother to child. Furthermore, understanding the transmission of HIV would give the women the opportunity to change misconceptions about the transmission of HIV:

"[T]hey take you aside, and they discriminate against you. No that one, they don't want to touch you or talk to you, sit next to you; you know, they have that kind of attitude."

It was clear that the women needed knowledge about the disease to understand it and to improve their management of the disease. This information would therefore not only increase their understanding of HIV, but would also allow women to take some measure of control over the disease's influence on their lives. This required specific skills.

Theme 2. Knowledge and skills needed regarding the physical management of HIV/AIDS

The second theme of health literacy needs addresses both knowledge and skills. This theme relates to the need to improve women's understanding of HIV/AIDS. Health literacy needs to physically manage HIV/AIDS include skills like setting an alarm to remind one to take medication or cooking a nutritious meal. Other practical aspects include the effective use of contraceptives. Three sub-themes were identified.

5.3. Suh-theme: effective self-care

Various topics such as maintaining a healthy lifestyle with regard to diet, exercise, general hygiene and psychological health were explored under this sub-theme. Preventing reinfection with HIV, going for follow-up visits and understanding the causes and management of conditions related to HIV were also considered priorities in self-care and maintaining health. This woman's revelation builds on an understanding of HIV:

"[A]nd then by not leading a healthy lifestyle, drinking too much alcohol, smoking, not using protection [condoms] and things like that, they take down your CD4 count and then the viral load goes up ..."

Basic skills such as preparing a nutritious meal, washing hands to avoid the spread of germs, or identifying clinic follow-up dates are fundamental in managing HIV/AIDS. Other skills include the correct use of a condom, basic wound care and the preparation of oral rehydration solutions to manage diarrhoea which commonly occurs in people living with HIV/AIDS. This sub-theme relates to ART adherence which ultimately maintains health in order to perform daily activities related to self-care.

5.4. Suh-theme: effective use of ART

The women explained that knowledge about ART would improve adherence to treatment:

"[T]he more they know about the ARVs, the more they learn about their health, their CD4 count and viral load. Because they learn that if I'm taking my ARVs properly, automatically my CD4 count is going to be getting higher and higher, and the higher it grows the healthier you become."

Skills that would improve adherence include reading the time or setting an alarm to remind women of treatment times. They also stated that knowledge about the effects of the treatment, interaction with other medications, and knowing the names of medications would allow them to develop strategies to manage side effects. This knowledge would also be instrumental in choosing safe additional medications where necessary and to ensure they take the correct treatment which would improve health outcomes.

5.5. Suh-theme: reproductive health

Distinct references to uniquely female issues led to this specific sub-theme. The women spoke about the importance of Pap smears, pregnancy prevention options and pregnancy care for women living with HIV/AIDS. The following quotes illustrate some controversial opinions and feelings on these issues which highlight the importance of health literacy in this specific area:

"I think to have a Pap smear is important. To my knowledge, a Pap smear they take [to check] that you don't have any of the diseases inside your womb . because there is much opportunistic disease ..."

"I don't know if I'm wrong, but I feel HIV-positive people shouldn't get pregnant. They should just get sterilised because this could be risky to both the parent and the child."

"I think you must first go to the doctor and check you immune system, your viral load, your body, how strong it is. Can it be possible [to become pregnant]? Yes it can be possible, but after the baby's birth will you be healthy enough to take care of the baby or will you die or will you or will the baby be healthy? Especially your health, the mother, the important one for the baby as well because if I ... die tomorrow, what about my baby?"

Women should be able to make decisions about expanding their families or taking the necessary precautions to prevent pregnancy. Also, they need to insist on reproductive health-care, specifically Pap smears, if they experience problems such as vaginal discharge or dyspareunia. This assertiveness is also important when caring for another person with HIV/ AIDS. It is extremely important to ensure that children exposed to HIV are monitored and receive the necessary treatment and care. Apart from aspects regarding the physical management and understanding of HIV/AIDS, the women also discussed the psychosocial aspects vital to the holistic well-being of women living with HIV/AIDS.

Theme 3. Psychosocial skills needed in living with HIV/AIDS

This final theme of health literacy needs comprises four sub-themes and addresses a number of aspects that influence health outcomes in women living with HIV/AIDS. These sub-themes build on an understanding of HIV as a disease and require the women to be proactive in living with HIV/AIDS.

5.6. Suh-theme: acceptance of HIV

Accepting the HIV diagnosis is an important step towards taking responsibility to live with HIV. One participant admitted that she wanted to commit suicide when she learned that she was HIV-positive, another withdrew from society and believed that life as she knew it was over:

"It wasn't easy then, but eventually I was going to get used to it [HIV diagnosis]. Like now it [fear] has passed. I live a normal life. I go to parties and weddings, I am fine and I live like any other person."

Women were aided in acceptance by a better understanding of HIV. The knowledge that there are others living with HIV/AIDS, physically meeting and talking to these people, as well as support from friends and families fostered their understanding of the disease. Women need encouragement to participate in activities that will help them accept their HIV status.

"If they just tell me it's not you [only] more people have HIV ... So I accept, I see more people when I come here [to the clinic] I see more people and we talk and talk and talk, so I accept."

5.7. Suh-theme: maintaining relationships

The women explained that relationships were their main support system and that they had to maintain these relationships effectively to sustain these support systems:

"I found out that my aunt was HIV-positive because she was taking the same medication as mine. I asked her about this and told her my status too. I told her we both have the same issue and we are scared to let people know about this."

Women in this study felt that these relationships would best be maintained by being honest about their HIV status, particularly with their partners. They reflected that it was easier to disclose their status if they were well informed about HIV/AIDS. Subsequently, disclosure made it easier for them to accept their status. The women also mentioned that increased community awareness about HIV/AIDS would make it easier to uphold their relationships. One explained that she could not share her status with her mother because her brother was banned from her mother's house due to his HIV status. She expressed her wish for a better informed society:

"The only thing that a person living with HIV needs is love. That is the most important thing you can give that particular person. Most people are discriminated against by their own families, they are told to use their own utensils, they don't share with them anything. And if people can change and show these people love, support and accept them as they are."

Understanding HIV/AIDS seems to lay the foundation for living with HIV/AIDS. Understanding of the disease is also improved by emotional and physical support. The findings indicate that women need to develop skills in talking to people about their HIV status. Talking about HIV allays the fears of the uninformed and allows women living with HIV to maintain close relationships with friends and family members.

5.8. Sub-theme:accessing resources

It is important for women to have the skills to learn about and access resources:

"I received support from C ... Hospice. They helped me a lot, if I ask them to come to my house, they do come to my house . they are the ones who have been giving me support, even now, when I need them, I go there. They also provide people with healthy food which are rich in vitamins."

These resources would include grants, food supplies, physical assistance, home care and even legal aid if required.

5.9. Sub-theme:entitlement in employment issues

While the women expressed their will to continue working, they also aired their frustrations in finding employment due to their HIV status. Yet again, the issue of community awareness about HIV/AIDS was raised. It was clear that the women needed skills not only to aid in increasing community awareness, but also to stand up for their human rights when being victimised because of their HIV status.

"They [the future employers] tested me and I tested positive [for HIV]. If you are positive you are not allowed to enter inside the firm [business]. Because of my status I was not employed."

The health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS, as interpreted from this study, are reflected in these themes and sub-themes. The importance of understanding HIV/AIDS in addressing these needs is portrayed by the subtle but persistent reappearance of this need throughout all the themes and sub-themes.

6. Discussion

With the number of HIV/AIDS-related deaths decreasing and an increasing number of people living with HIV/AIDS, there is a need for health education programmes specifically designed for people living with HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS education customised to a specific person or condition has been proven to have a positive influence on health behaviour and outcomes, as well as health-related decision-making. Health information should be customised for the skills and needs of the people living with HIV/AIDS (Ryan et al., 2014, p. 226) with consideration of their literacy levels (Lambert & Keogh, 2014, p. 36). The women participating in this study had varying levels of education. Their literacy levels were not determined.

Women in this study expressed a need to improve their knowledge about HIV/AIDS in order to understand the disease and develop knowledge and skills to physically manage HIV/AIDS. Kalichman et al. (2000,p.328)supportthene-cessity for people living with HIV/AIDS to have improved knowledge about the disease to enhance their self-efficiency as well as their adherence to ART. It has also been found that a higher level of health literacy correlates with a better understanding of HIV/AIDS (Kalichman et al., 2000,p.329) and that women with HIV/AIDS are interested in the changes the disease will cause in their bodies (Enriquez, Lackey, & Witt, 2008, p. 39). The literature indicates that people who start to understand HIV/AIDS want to know more about how the disease affects their bodies and corresponds with the need identified in this study to know about HIV/AIDS pathophysiology and progression. An important influencing factor is consideration of the literacy and education levels of the women, which would influence the level of complexity with which knowledge related to HIV/AIDS and ART is to be transmitted in this context (Lambert & Keogh, 2014,p.36).

Other studies postulate that knowledge about aspects of HIV/AIDS, such as the transmission of HIV or the interrelation of the CD4 count and the viral load, could influence health behaviour and choices in sexual health (Kalichman et al., 2000, p. 329) and reproductive health (Petroll, Kare, & Pinkerton, 2008, p. 229) of people living with HIV/AIDS. Kalichman et al. (2000, p. 329) also found that people on ART with a poor understanding of the disease believed that they could no longer transmit HIV once their viral load was suppressed. These misconceptions emphasise the importance of understanding HIV/AIDS and its progression, and customising information to the level of understanding and needs of the population addressed.

In this study, women identified self-care as a health literacy need. While concerns such as self-care in living with HIV/ AIDS with specific reference to issues such as diet, general hygiene and the prevention of opportunistic infections are discussed in the literature (Sebitloane & Mhlanga, 2008, p. 495; WHO, 2008, p. 35), it is not described as a health literacy need for women living with HIV/AIDS. However, it has been proven that an understanding of the direct and positive influence of health behaviours on health status has encouraged better general self-care in women living with HIV/AIDS (Tufts, Wessell, & Kearney, 2010, p. 42). Self-care is influenced by the application of knowledge and skills towards health-related decisions and behaviours. It can therefore be concluded that knowledge and skills in self-care are a valid health literacy need.

The women in this study identified the need to expand on ART-related knowledge and skills which corresponds to the issues described by Sarna and Weiss (2007, p. 14) such as knowing how to take medication, the importance of adherence, side-effects and their management, and how to access ART services. Van Dyk (2011, p. 7) found that a good educational programme and a subsequent understanding of ART increased adherence to the treatment and in effect the health status of people living with HIV/AIDS. Therefore, it would be beneficial for women living with HIV/AIDS to understand the actions of the medication, as well as the effects other treatment may have on the functioning of ART. Women should also be coached to identify the time when treatment should be taken and to calculate the right amount of medication to take with them when they are travelling.

Reproductive health issues were also identified as a health literacy need. Research has shown that women who understand the use of regular cervical cancer screening, the need to prevent unintended pregnancies and re-infection with HIV are more likely to accept and participate in these routines (Ezeanolue, Stumpf, Soliman, Fernandez, & Jack, 2010,p.4; Massad et al., 2010, p. 70). Again, the level of literacy and education would greatly impact on the extent of health literacy needs; needs might simply refer to knowledge but might require skills such as checking for intrauterine device strings, breastfeeding or breast self-examination. It is thus vital to expand reproductive health literacy to include contraceptive care, pregnancy-related issues, infant care and sexual health. This is particularly important for women living with HIV/AIDS so that a woman who utilises any one of the services would have access to all the related services and information (UNAIDS., 2012a, pp. 45; 66). Previous studies (Maneesriwongul et al., 2004; Nokes et al., 1997) did not identify reproductive health as a health literacy need, but Myer, Rabkin, Abrams, Rosenfield, and El-Sadr (2005, p. 142), Sebitloane and Mhlanga (2008, p. 493) and UNAIDS. (2012a, pp. 45 & 66) support the integration of these services for holistic reproductive healthcare.

In this study, psychosocial skills were identified as a health literacy need. The psychosocial skills include acceptance and disclosure, maintaining relationships and the utilisation of resources. Tufts et al. (2010, p. 43) raise the importance of emotional health in people living with HIV/AIDS. Enriquez et al. (2008, p. 42) also emphasise the importance of psychological healthcare in women living with HIV/AIDS by describing the constant emotional battle of living with HIV versus dying from the disease. The positive influence of sound psychological health and acceptance also plays a vital role in the health literacy needs of women living with HIV/AIDS (Van Dyk, 2011, p. 7). Enriquez et al. (2008, p. 40) write about the role of disclosure in acceptance and the importance of acceptance in surviving with HIV/AIDS. The healing nature of disclosure is also commended by Tufts et al. (2010, p. 43). The literature further emphasises that maintaining good relationships -and therefore support systems - ease the burden of living with HIV/AIDS (Van Dyk, 2011, p. 7). The WHO (2008, p. 8) considers the development of communication skills as an important aspect in living with HIV/AIDS. These skills might encourage women to increase community awareness of HIV/ AIDS, but more importantly, will allow them to express their needs and enable them to access the necessary resources. The WHO (2008, p. 12) stresses the importance of preventing regression in health due to a lack of resources. Findings by Nokes et al. (1997, p. 49) support the notion that women should be aware of and able to access resources. This includes assistance where human rights were violated or employment was refused because of HIV status (UNAIDS., 2012a, p. 66).

The health literacy needs identified by women in the current study support the findings of earlier studies (Maneesriwongul et al., 2004; Nokes et al., 1997). UNAIDS. (2012a, pp. 45 & 66) also describes many of these aspects in the 2012 global report on the AIDS epidemic. The current study identified information (knowledge and skills) that should be included in the health education provided to women that will enhance their health literacy and enable them to make health-related decisions that they are satisfied with. Autonomy in health-related decision-making is especially important considering the traditional role women play in healthcare. The role of a basic understanding of HIV/AIDS is a vital point of departure in health literacy about HIV/AIDS and signifies the need for reproductive health literacy among women living with HIV/AIDS.

7. Limitations of the study

The sample size was eight women; therefore the findings of this study are applicable to a small group of women who shared similar socioeconomic backgrounds. The use of a translator was unavoidable, and it is possible that some information was lost or omitted in the translation process.

The study did not investigate the role of culture, values and beliefs in health literacy. Such a study would require a more ethnographic approach and the inclusion of a diversity of South African cultures.

8. Recommendations

Based on the findings of the study the following recommendations are made for nursing practice, education and research.

8.1. Nursing practice

The themes identified in this study provide nurses with an array of relevant topics for the health education of women who live with HIV/AIDS. Topics should include basic knowledge about the disease and its pathophysiology as well as identifying skills required to involve women in their healthcare. For example, considering women's physiological risk for HIV infection, reproductive health issues such as contraception, cervical cancer screening and pregnancy care are vital in addressing the health literacy of women living with HIV/AIDS. Women should be encouraged to know more about their bodies and should be taught skills such as breast self-examinations and responsible contraceptive use to develop their autonomy in healthcare-related matters. It is particularly important for nurses to not only give information, but to also teach them important skills for attaining health. HIV/AIDS health-related material used for education should be evaluated for its appropriateness with regard to the level of language, level of education, and the needs of women. Information should be presented clearly and concisely using plain language that can be easily understood despite level of literacy (Ryan et al., 2014, p. 226). Healthcare providers should ensure that health information allows women to become active participants in their own health and healthcare (Ryan et al., 2014, p. 226).

8.2. Nursing education

The nursing curriculum should include outcomes related to promoting the health literacy of women living with HIV/AIDS. The curriculum could equip future nurses with the relevant skills to enable them to provide relevant and appropriate health education to women based on the themes in this study and with consideration of the level of literacy of the healthcare users.

8.3. Nursing research

It is recommended that future research include a quantitative study based on the themes identified in this study, including a larger representative sample. Furthermore, the inclusion of men in a similar study would be valuable as the researcher observed men at the wellness clinic who showed an interest in also expressing their health literacy needs.

Future studies should further investigate the preferred methods for delivery of health-related information.

A study of the roles and influences of various South African cultures on HIV/AIDS-related health literacy, treatment adherence and perceptions would also be invaluable in the South African healthcare context.

9. Conclusion

Evidence from the current study suggests that a basic understanding of HIV/AIDS as a disease is fundamental in addressing health literacy related to aspects of living with HIV/AIDS such as adhering to ART, preventing transmission of HIV and disclosing HIV status. Health literacy is a very broad concept and the current study focused on health information needs. Other implications of the study involve providing comprehensive health literacy to women living with HIV/ AIDS, which includes the development of skills such as meal planning, basic wound care and calculating medication times.

This study confirms the findings of other similar studies and adds additional evidence for the need to develop health literacy programmes specifically for women living with HIV/ AIDS. Health literacy is crucial to improve the health outcomes of women living with HIV/AIDS since an increasing number of people, particularly women, are living with HIV/ AIDS. In the light of women's vital role in caring for their families and making health-related decisions, the words of well-known Ghanaian philosopher and teacher, Dr Kwegyir-Aggrey (Nyamindie, 1991), come to mind: "Educate a woman, educate a nation".

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by University-based Nursing Education South Africa (UNEDSA) as part of the Community Oriented Nursing Education Programme in Women and Child Health of the Universities of Limpopo (Medunsa Campus) and Pretoria.

REFERENCES

Bachelet, M., Gatdi-Mallet, J., & Sidebé, M. (2012). Foreword in UNAIDS, women out loud: How women living with HIV will help the world end AIDS. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2012/20121211_Women_Out_Loud_en.pdf. [ Links ]

Baker, D. W. (2006). The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 878-883. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. California: Sage. [ Links ]

Enriquez, M., Lackey, N., & Witt, J. (2008). Health concerns of mature women living with HIV in the Midwestern United States. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 19, 37-46. [ Links ]

Erhardt, A. A., Sawires, S., McGovern, T., Peacock, D., & Weston, M. (2009). Gender, empowerment, and health: what is it? How does it work? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51,96-105. [ Links ]

Ezeanolue, E. E., Stumpf, P. G., Soliman, E., Fernandez, G., & Jack, I. (2010). Contraception choices in a cohort of HIV+ women in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Contraception, 84,94-97. Retrieved from http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.012. [ Links ]

Farlex. (2013). The free dictionary: Need. Retrieved from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/need. [ Links ]

Finset, A., & Lie, H. C. (2010). Health literacy and communication explored from different angles (Editorial). Patient Education and Counselling, 79,1-2. [ Links ]

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS see UNAIDS. Kalichman, S. C., Benotsch, E., Suarez, T., Catz, S., Miller, J., & Rompa, D. (2000). Health literacy and health-related knowledge among persons living with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 18, 325-331. [ Links ]

Krefting, L. (1991). Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45, 214-222. [ Links ]

Lambert, V., & Keogh, D. (2014). Health literacy and its importance for effective communication. Part 2. Nursing Children and Young People, 26(4), 32-36. [ Links ]

Maneesriwongul, W., Panutat, S., Putwatana, P., Srirapo-Ngam, Y., Ounprasertpong, L., & Williams, A. B. (2004). Educational needs of family caregivers of persons living with HIV/AIDS in Thailand. Journal ofthe Association ofNurses in AIDS Care, 15,27-36. [ Links ]

Massad, L. S., Evans, C. T., Wilson, T. E., Goderre, J. L., Hessol, N. A., Henry, D., et al. (2010). Knowledge of cervical cancer prevention and human papillomavirus among women with HIV. Gynecologic Oncology, 117,70-76. [ Links ]

Myer, L., Rabkin, M., Abrams, E. J., Rosenfield, A., & El-Sadr, W. M. (2005). Focus on women: linking HIV care and treatment with reproductive health services in the MTCT-Plus Initiative. Reproductive Health Matters, 13, 136-146. [ Links ]

Nokes, K. M., Kendrew, J., Rappaport, A., Jordan, D., & Rivera, L. (1997). Development of an HIV educational needs assessment tool. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 8,46-51. [ Links ]

Nyamindie, J. K. E. (1991). African proverb of the month: September 1991. Retrieved from http://www.afriprov.org/index.php/african-proverb-of-the-month/25-1999proverbs/146-sep1999.html. [ Links ]

Paasche-Orlow, M. K., & Wolf, M. S. (2007). The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(1), S19-S26. [ Links ]

Petroll, A. E., Kare, C. B., & Pinkerton, S. D. (2008). The essentials of HIV: a review for nurses. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 31, 228-235. [ Links ]

Plan Associates. (2005). [Anonymous] regional spatial development framework for [Anonymous]. draft report. [ Links ]

Polit, D. E., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. [ Links ]

Ryan, L., Logsdon, M. C., McGill, S., Stikes, R., Senior, B., Helinger, B., et al. (2014). Evaluation of printed health education materials for use by low-education families. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 46(4), 218-228. [ Links ]

Sarna, A., & Weiss, E. (2007). Current research and good practice in HIV and AIDS treatment education. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001497/149722E.pdf. [ Links ]

Sebitloane, H. M., & Mhlanga, R. E. (2008). Changing patterns of maternal mortality (HIV/AIDS related) in poor countries. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 22, 489-499. [ Links ]

Tufts, K. A., Wessell, J., & Kearney, T. (2010). Self-care behaviors of African American women living with HIV: a qualitative perspective. Journal ofthe Association ofNurses in AIDS Care, 21, 36-52. [ Links ]

UNAIDS & WHO. (2009). AIDS epidemic update. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/report/2009/jc1700_epi_update_2009_en.pdf. [ Links ]

UNAIDS.. (2012a). Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/publications/2012/. [ Links ]

UNAIDS.. (2012b). Women out loud: How women living with HIV will help the world end AIDS. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2012/20121211_Women_Out_Loud_en.pdf. [ Links ]

Van Dyk, A. C. (2011). Difference between patients who do and do not adhere to antiretroviral therapy. Journal ofthe Association of Nurses in AIDS Care,1-14. Retrieved from http://dx.doi:10.1016/j.jana.2010.22.008. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2007). HIV/AIDS programme. Strengthening health services to fight HIV/AIDS. WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdf. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2008). Essential prevention and care interventions for adults and adolescents living with HIV in resource-limited settings. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/EP/en/index.html. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2009). Executive summary women and health, todays evidence tomorrows agenda. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/WHO_IER_MHI_STM.09.1_eng.pdf. [ Links ]

Zarcadoolas, C., Pleasant, A., & Greer, D. S. (2005). Understanding health literacy: an expanded model. Health Promotion International, 20, 195-203. [ Links ]

Received 9 March 2015

Accepted 11 March 2015

Available online xxx

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +27 012 521 3755; fax: +27 082 404 4720. E-mail addresses: judythompson09@gmail.com (J. Thompson), havengay@tut.ac.za (Y.(S. Naude).

1 Tel.: +27 012 3824280; fax: +27 0825092028.

2 Fax: +27 082 447 6279.

3 Words in brackets are the researcher's own and were added for clarification.