Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.19 no.1 Cape Town ene. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v19i1.811

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

doi:10.4102/hsag.v19i1.811

A qualitative study of the factors influencing the global migration of anatomical pathologists in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Nadeem CassimI; Shaun RuggunanII

IProgramme for Industrial, Organisational and Labour Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Campus, South Africa

IIDiscipline of Human Resources Management, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The aim of the present study was to identify the factors that influence the globalmigration of South African anatomical pathologists working in the province of KwaZulu- Natal.

OBJECTIVE: The present study answered the question 'what factors influence Kwazulu-Natal-based histopathologists to emigrate out of South Africa?', thus providing insight into an under-researched medical specialisation.

METHODS: A qualitative approach and purposive sampling were used. Data included 11in-depth interviews with histopathologists working in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), and one interview with a former KZN-based histopathologist now working in the United States. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The data were coded for patterns, and these patterns generated themes. The processes of coding and thematic generation were iterative.

RESULTS: Six themes were discovered from the data. Of these, five themes suggested reasonsfor the potential emigration of histopathologists. : lack of recognition by clinical doctors, lack of career-pathing opportunities, the deterrent of compulsory service in the public sector upon qualifying, socio-economic and political instability in South Africa, and endemic levels of crime. A sixth theme revealed that remuneration was not a deciding factor as to whether histopathologists choose to emigrate.

CONCLUSIONS: Remuneration was not revealed to be a reason for emigration, as these specialists' salaries are commensurate with global salaries. The findings, whilst not generalisable, suggest that more work needs to be done on the human relations aspects of retention for these medical specialists. This has implications for human resources for health policy.

OPSOMMING

AGTERGROND: Die doel van hierdie artikel is om die faktore te identifiseer wat die globale migrasie van Suid-Afrikaanse anatomiese patoloë wat in die provinsie van KwaZulu-Natal werk, beïnvloed.

DOELWIT: Hierdie artikel beantwoord die vraag: 'Watter faktore beïnvloed histopatoloë wat in KwaZulu-Natal gebaseer is om uit Suid-Afrika te migreer?', en verskaf sodoende insig in 'n ondernagevorste mediese spesialisasie.

METODES: 'n Kwalitatiewe benadering en doelgerigte steekproefneming is gebruik. Die data het 11 diepgaande onderhoude met histopatoloë wat in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) werk en een onderhoud met 'n voormalige KZN-gebaseerde histopatoloog wat nou in die Verenigde State werk, ingesluit. Die onderhoude is opgeneem en getranskribeer. Die data is vir patrone gekodeer en hierdie patrone het temas gegenereer. Die koderingsproses en tematiese generering was herhalend.

RESULTATE: Ses temas is in hierdie data ontdek. Hiervan het vyf temas redes vir die moontlike migrasie van histopatoloë voorgestel. Dit sluit in gebrek aan erkenning deur kliniese dokters, gebrek aan loopbaangeleenthede, die afskrikmiddel van verpligte diens in die openbare sektor na kwalifisering, sosio-ekonomiese en politieke onstabiliteit in Suid-Afrika, en endemiese misdaadvlakke. 'n Sesde tema het aan die lig gebring dat vergoeding nie 'n beslissende faktor is in histopatoloë se keuse om te migreer nie.

GEVOLGTREKKINGS: Vergoeding blyk nie 'n rede vir migrasie te wees nie, aangesien die salarisse van hierdie spesialiste in ooreenstemming met globale salarisse is. Hoewel dit nie veralgemeenbaar is nie, stel die bevindings voor dat meer werk aan die menseverhouding-aspekte gedoen moet word om hierdie mediese spesialiste te behou. Dit het implikasies vir menslike hulpbronne in gesondheidsbeleid.

Introduction and background

The aim of the present study was to identify potential factors that contribute to the global migration of South African histopathologists in KwaZulu-Natal. The literature on the global migration of health professionals focuses on a range of medical health professionals such as nurses and clinical doctors (Lu et al. 2005; Pillay 2009). However, the literature tends to homogenise medical doctors, with limited regard for their type of specialisation. Where specialisation is mentioned, it exclusively refers to clinical specialities (Erasmus & Hall 2003; Chikanda 2006). The present study focused on medical laboratory specialists, specifically histopathologists. As such, it is one of the first empirical studies in South Africa to investigate the reasons why non-clinical specialists such as histopathologists may want to emigrate from South Africa. The present study contributes to the debates on human resources management for health by suggesting that it may not be empirically useful to consider medical doctors as a monolithic category, as argued by Ruggunan (2013):

... treating medical doctors as a monolithic category, researchers have ignored the ways in which medical specialisations of doctors contribute to their professional milieus and the ways they may experience their medical specialisations. (p. 99)

The present study contends that by disaggregating doctors by specialisation a fuller picture emerges as to why certain specialisations or categories of doctors, for example non-clinical doctors like histopathologists, may be susceptible to global migration. Empirical work that investigates why non-clinical medical specialists migrate is limited in both the global and South African literature; the focus in the literature tends to be on clinical health workers.

South Africa's healthcare system is undergoing a human resource crisis, which is hampering the accuracy and quality of the country's healthcare (George et al. 2009). The crisis is attributed to the shortage and loss of skilled medical personnel; however, this literature focuses mainly on clinical medical personnel. It can be contended that the unreported shortage of medical laboratory specialists (Hagopian et al. 2004) further exacerbates the crises. By medical laboratory specialists, this refers to medical doctors with postgraduate specialisations in histopathology, virology, microbiology and chemical pathology. Medical laboratory specialists make a profound contribution to the national healthcare of South Africa, yet remain an invisible part of the healthcare chain.

The present study focused on one type of medical laboratory specialist, the histopathologist, also knows as the anatomical pathologist. Histopathologists focus on the diagnoses of diseases, based on examination of human tissue samples; they examine tissues from patients through biopsies and autopsies. Anatomical pathologists are required to possess a broad understanding of the pathological, as well as the clinical aspects of diseases. In addition to this, contemporary-day pathology also requires anatomical pathologists to perform cytology, which is the examination of specimens of separated cells. Most of the duties performed by anatomical pathologists involve diagnosis 'by eye' of human tissue. Through diagnosis by eye (as opposed to by new technologies), these specialists are required to obtain results on the occurrence, stages, symptoms and treatment of diseases (Hale 2009). It takes an average of twelve years to qualify as a histopathologist in South Africa. The first six years of the training process is spent acquiring an undergraduate medical degree. Thereafter, doctors serve a two-year internship and a one-year period of community service. Last, once they have completed their community service, graduates undergo specialist training in their respective medical laboratory fields for four years.

Histopathologists play an integral role in ensuring accurate and appropriate healthcare in the national healthcare system due to their influence in clinical decision making and medical diagnosis. The absence of their diagnosis and expertise often results in misdiagnosis and patient deaths, because clinical doctors across a spectrum of specialisations rely on the expertise of medical laboratory specialists in their decision-making processes (Bates & Maitland 2006). Considering the prevalence of infectious diseases in South Africa, such as HIV and/or AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and cancer, the role that medical laboratory specialists play in the country's national healthcare becomes even more integral because they are considered to be a vital resource required in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases (Petti et al. 2005). However, the loss of these specialists from the South African labour market has contributed to a major health imbalance by posing threats on the quality and accuracy of the national healthcare system.

South Africa is currently experiencing a shortage of histopathologists, as well as many other clinical and non-clinical specialists (HPCSA 2011; The South African 2010); nationally there are only 245 pathologists (HPCSA 2011). In KZN, the numbers are 23 (the patient ratio in KZN is 1:460 589). Whilst official statistics state that the number of pathologists in KZN is 26 (HPCSA 2011), primary findings of the present study have verified that there are 23. Medical laboratory specialists migrate to countries in response to push-pull factors (Allsop et al. 2009). However, these push-pull factors are often informed by a range of non-financial reasons. Non-financial reasons for migration increasingly inform the scope of work performed by human relations theorists. These theorists argue that histopathologists migrate in response to their employment needs, such as: recognition of the role the profession plays in the healthcare chain; training and educational needs; infrastructure; technology; linguistic competence (i.e. English); workload and career advancement (Beckering & Brunner 2003; Guidi & Lippi 2006; Plebani 2010). South Africa's global reputation as a quality supplier of doctors and medical specialists means that South African healthcare practitioners are a sought after commodity in the global labour market (The South African 2010; Arnold & Lewinsohn 2010; Rogerson 2007; George et al. 2009). For example, a study conducted in the United States of America depicts South Africa as one of the chief senders of laboratory specialists to the United States medical labour market. Statistics show that only ten medical schools globally contribute 79.4% of the medical laboratory specialists practicing in the United States (Hagopian et al. 2004); of these ten schools, three are South African. These three are specifically targeted to recruit potential specialists to the United States.

Compounding the shortage of histopathologists in South Africa is the rapid ageing of the current cohort of specialists. Most countries cite the ageing laboratory workforce as an issue of great concern. In this regard, South Africa's ageing medical laboratory specialists is reflective of First World patterns. In South Africa, this issue is magnified through the country's inability to adequately retain and recruit existing and young medical laboratory specialists. This failure, along with the rapid ageing of the country's current specialists who are approaching retirement age, will further impact the current shortage of these specialists in South Africa in two key ways: by expanding and increasing the demand for these specialists; and resulting in a massive loss of experience and expertise in the country's healthcare system.

Interviews conducted for the present study suggest that there comes a period in the careers of anatomical pathologists where these specialists believe that they have reached a stage in their qualifications that allows them to become 'super specialists'. Hence, a large number of these specialists resort to emigrating to countries that allow them to pursue a career path that allows them to super specialise; for example, specialising in skin pathology only. A small number of anatomical pathologists have emigrated from South Africa to become super specialists in other countries. If South Africa was able to provide these opportunities to its specialists, then it would be able to retain a larger number of medical laboratory specialists because they would not have to emigrate in search of super specialist's opportunities. Advanced career development and developing a super specialisation is possible in the South African and KwaZulu-Natal context, as histopathologists are trained in public sector academic hospitals. However, the challenges of high workloads and poor support systems (Ashmore 2013; IOL 2009; De Villiers & De Villiers 2004) means that such ambitions are not always actionable.

Additionally, doctors have stated that returning to South Africa would be considered as taking a step back in their careers (HPCSA 2011; The South African 2010). They expressed that the technology, infrastructure, and working conditions that they experience overseas in more-developed countries (such as Saudi Arabia) are far more conducive to their careers than the conditions in South Africa. They elaborated that in South Africa, working environments do not allow specialised practice, and even though they are highly specialised and skilled, their work gains no recognition and exposure (Rogerson 2007).

Research methodology

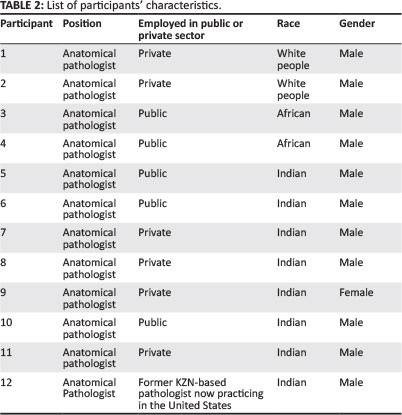

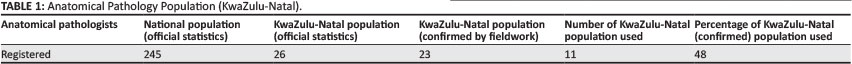

The present study was part of a larger study funded by the National Research Foundation. The larger study investigated the labour market and professional milieu for chemical pathologists, histopathologists and medical microbiologists in KwaZulu-Natal. The present study represents empirical work performed on histopathologists. Both the larger study and the present study adopted a case-study research design. Case studies allowed for an in-depth, primarily qualitative and context-based analysis of the research questions. The official population consisted of 23 anatomical pathologists in KZN. Out of this population, the researchers sampled purposively 11 anatomical pathologists (48%) and one former South African histopathologist now practicing in the United States. Table 1 shows the population of anatomical pathologists nationally and in KwaZulu-Natal, whilst Table 2 lists the features of pathologists that were sampled for this study.

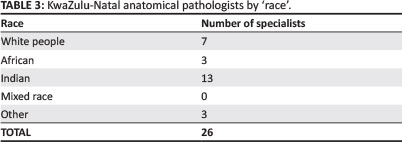

The sample that was selected indicated that mainly South African Indian males were interviewed. However, when compared to the demographics of the population, it can be seen that this is not a biased sample, but rather reflects the skewed racial labour market for histopathologists in KZN. This skewness is the result of the racialised medical training and education that occurred under Apartheid. Whilst Black African doctors were able to study and qualify at the former Natal Medical School (Brier & Wildschut 2006), their access to postgraduate or specialist fields of study remained limited. This was due to racialised gatekeeping into medical specialisation and also to the fact that Black African doctors came from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and, hence, needed to earn salaries rather than study further (Brier & Wildschut 2006). Indian males, whilst considered to be a disadvantaged group under Apartheid, still enjoyed more economic privilege within the province, which included less impeded access to further study. The study conjectures that the reason the discipline is male dominated provincially reflects the values of a patriarchal society and demonstrates the male dominance of the medical profession at large. A summary of participants by race is provided in Table 3 below.

Data Collection

The primary method of data collection used was in-depth interviews. Interviews provide a source of rich and 'thick' data (Babbie 2011). An interview schedule with guide questions was prepared beforehand. All participants were asked the same key questions. Probing questions were used to prompt participants when required. Interviews were recorded with participants' permission and transcribed. Each interview lasted on average 37 minutes.

Data Analysis

Thematic Analysis, as explicated by Braun and Clarke (2006), was used. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The researchers then immersed themselves in the data by reading and rereading the data. The transcripts were then coded manually for common patterns to produce a set of candidate themes. Whilst recurring concepts and ideas were coded as patterns, minority views in the data were also noted. These temporary themes were then revised and further reduced through an iterative process of recoding the data, also known as progressive coding.

Trustworthiness of the data

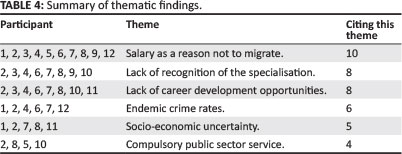

Both investigators coded the data independently to generate themes. Both sets of themes were then compared to achieve a measure of credibility and trustworthiness of the data analysis process. After the initial coding process, both researchers discussed how to label, collapse and disaggregate themes where needed. For example, the theme 'socio-economic issues', was disaggregated to generate a subtheme of 'endemic crime as a driving factor of migration'. A high-participation rate of 11 of 23 histopathologists, or 48% of the population, contributed to the dependability of the data. Table 4 (below) demonstrates the strategies used to ensure trustworthiness.

Ethical considerations

Full ethical clearance was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal ethics committee for the study. The ethical clearance number is HSS/1187/010. Participants all signed informed consent forms, and were advised that they could withdraw from the study at any point. All identities have been fully anonymised in all reported data.

Results

The table below summarises the findings from the interview data.

The following themes were discovered from the interviews with participants. It was particularly interesting to note that participants cited non-remunerative reasons as key factors influencing their reasons to emigrate or not. This certainly challenges the popular notion that money is the key driver of migration amongst highly skilled professionals.

Salary as a reason NOT to migrate

The quote below is an exemplar of this theme:

'Ja the recruitment strategies ... we had a salary adjustment which included everyone. So the salaries are not an issue, we compare favourably with the department of health.' (interview: P2)

In addition, some participants commented that 'greener pastures' (interview: P3, P4, P5) do not always exist outside South Africa. The global North, in their opinion, does not necessarily offer higher salaries when a range of other factors, such as purchasing parity in a foreign currency and the cost of living, are considered. This was emphasised by a former South African anatomical pathologist who stated that there are no financial gains for anatomical pathologists emigrating out of South Africa. He stated that whilst specialists may earn more abroad due to higher currencies (such as pounds in the United Kingdom); the real wage that specialists earn aboard is actually equivalent to the salaries that South African anatomical pathologists earn. Additionally, he added that there are instances where South African salaries are even higher than overseas salaries for anatomical pathologists (interview: P9, P12).

Another anatomical pathologist stated:

'Look I know of a lot of anatomical pathologist that have gone overseas. There ... I know of a number who have gone over for socio economic reasons, for better schooling, I know some who have been affected by crime here in South Africa and decided to emigrate. I know of a good number who have gone to take senior academic posts in institutions overseas. Generally speaking not many of them go for the wages. It is well remunerated in South Africa comparative to the overseas market so pay is often not a determining factor. It is other issues ...' (interview: P7)

Misconceptions of the value and contribution of histo-pathology

A perception exists amongst the histopathologists that were interviewed that South African clinical doctors and the public does not sufficiently recognise the contribution of medical laboratory specialists in the healthcare chain:

'There is a misconception of laboratory fields. For example, many medical school graduates and even clinical doctors have a misconception of what anatomical pathology actually is. They have a perception that anatomical pathology is a field that only requires one to be engaged in post mortems of human bodies. However, there remains a huge divide between this perception and what the discipline is actually about. Due to this misconception, medical graduates are reluctant to choose anatomical pathology as a field to specialise in.' (interviews: P10)

Another histopathologist added:

'Due to the negligence of medical schools to expose students to the discipline, there are many instances where registrars that have chosen anatomical pathology or virology as a field to specialise in drop out. This is because they have no prior knowledge of what the discipline consists of.' (interview: P11)

Migration as a strategy to expand skill base

Histopathologists also cite career mobility and development as a reason to emigrate out of South Africa. For example, anatomical pathologists emigrate to experience a larger and different spectrum of diseases, as well as to super specialise:

'Principally, because in our country in terms of medicine among most of the disciplines, the type of pathology that we see in South Africa is very different from the type of pathology seen in those countries that I mentioned, in the UK and US. And I think a lot of doctors go because they want to see something different. They want to see things that they haven't seen during their training and during their teaching. So a lot of doctors go there to see a wider range of diseases and to be able to manage those diseases than here.' (interviews: P8).

Another stated:

'I mean in terms of spectrum of diseases. They type of spectrum of diseases that you see overseas is very different to what our community sees, largely because our diseases are driven often by HIV, whereas in other settings even the people who are HIV infected tend to have a different spectrum of disease. I also think the research opportunities abroad are much more than what we have here.' (interview: P6)

Socio-economic conditions in South Africa

Medical laboratory specialists emigrate from South Africa in response to the countries poor service provision in areas such as: water, electricity, healthcare, safety and transport. Specialists have migrated to countries such the United Kingdom, which offers more efficient basic services:

'We have lost a lot of good anatomical pathologist to overseas. The main draw cards there are social, or social economic, shall I say as well as to a certain extent academic, improved status and the like. But to say most anatomical pathologist are leaving for either better packages overseas, that is relatively minor. The majority are because they are not happy with the socio-economic conditions in South Africa.' (interview: P8)

Another stated:

'I think it is just the social and political factors in South Africa versus those countries. Those countries offer a better standard of living, better quality of living and security. So I think its not just the discipline itself, I don't think those are the reasons a lot of the doctors leave, I think its just greater socio-economic reasons that any other average South African would choose to leave the country.' (interview: P11)

Endemic crime rates in South Africa

Half of the participants cited crime in South as the predominant reason behind the loss of South African histopathologists to other countries. The quotes below exemplify this theme:

'I know a lot of guys that have migrated. And its the general political set up here, which, the crime and all that sort of thing. That is a factor. We certainly lost partners from here. We have lost five partners from here that went to Australia. Some ten years ago but some more recently and they were concerned about the crime here.' (interview: P12)

'It's more social issues like crime and safety, issues around my family rather than issues at work. I think most people are leaving because of that not because of work issues.' (interview: P1)

Discussion

Salaries were not mentioned by the sample who were interviewed as an explicit reason for emigrating out of South Africa. Ten of the eleven histopathologists from KwaZulu-Natal expressed satisfaction with their income. Participants indicated that they are well compensated in the private and public sectors. This finding does not support the literature, which indicates that poor salaries in the developing world are a chief reason for global migration (Awases et al. 2004; Bourgain et al. 2008; Collins 2002; Hamilton 2004; Roenen et al. 1997). According to participants interviewed, a unique aspect about the remuneration of these specialists is that they are well remunerated in both the public and private sectors, with salary scales being comparable. This is also not in keeping with some of the empirical work on the reasons for the sector switching and global migration of health professionals (Ashmore 2013; Pillay 2009; Wildschut 2010). This is potentially an important area worthy of further investigation, as it has implications for retention policies.

It seems that there is a point past which remuneration is no longer a deciding factor in whether these doctors emigrate. This is in keeping with the study performed by Marshall and Harrison (2005), which empirically demonstrated that financial incentives don't always work as motivating factors for health professionals. Remuneration is cited in the literature (Wildschut 2010; Brier & Wildschut 2006; Ferrinho et al. 2004; Vujici et al. 2004; George et al. 2009) as one of the primary push factors for South African doctors. For example, a senior doctor working in South Africa would earn approximately $1486, whereas he and/or she can earn these equivalent amounts in US dollars: $3056 in the US; $2832 in Australia; $2812 in Canada; and $2567 in the UK. This indicates that the salaries earned in more-developed countries are almost double the salaries that doctors earn in South Africa (Pillay 2007; HPCSA 2011). South African general practitioners are poorly remunerated compared to their equivalents in the global North. For example, a senior doctor working in South Africa would earn approximately $1486, whereas he and/or she can earn these equivalent amounts in US dollars: $3056 in the US; $2832 in Australia; $2812 in Canada; and $2567 in the UK. This is almost almost double the salaries that doctors earn in South Africa (Pillay 2007; HPCSA 2011).

However, histopathologists in South Africa are highly remunerated when compared to non-specialist doctors (even those at a senior level), which means, as one participant suggested, that their salaries can match (if not better) the salaries of anatomical pathologists in many developed countries. Empirical evidence to support this claim is not available; however, Hale (2009), a former head of histopathology at the University of Witwatersrand, in his review article on the state of histopathology in South Africa provided an optimistic assessment of the discipline (in terms of job complexity and training) that is at odds with the views expressed by participants in the present study.

In a qualitative study of South African medical specialists job-satisfaction levels in the public and private sectors, Ashmore (2013) supported the idea that higher salaries may not always serve as the best satisfiers for medical specialists. His work showed that sometimes the complexity of public sector work overrides financial incentives as a satisfier of work. Ashmore's work did not specifically examine job satisfaction of histopathologists, but looked at a sample of 74 medical specialists that practice in both the public and private sector in Cape Town. His study is one of the few qualitative studies to investigate job satisfaction of medical specialists in South Africa.

The disparity in public and private sectors can be accounted for by the for-profit nature of the private sector. The private sector services patients with private medical aids or sufficient cash to pay for their healthcare; the efficiency and, often, the quality of healthcare is better. The public sector, on the other hand, is resources-constrained both in terms of human and financial resources. This clearly has a differential impact on patient healthcare.

Misconceptions of the value and contribution of histopathology to the healthcare chain was cited as a second major social factor resulting in the failure to retain and recruit these medical laboratory specialists in South Africa. Respondents emphasised that many anatomical pathologists that have emigrated abroad have done so due to the negligible recognition that their expertise attained in South Africa. Perceptions of peer recognition of expertise are an important factor in motivating these professionals to remain in their practices. This is in keeping with evidence from the literature (Bonner 2003; Horowitz et al. 2003; Humphrey & Russell 2004), which demonstrates that recognition of expertise is an important determinate in the recruitment and retention of health professional workers. Whilst anatomical pathologists may be medical specialists, a large number of these specialists were also involved in academic work as researchers, heads of departments and professors. However, despite the contributions that they have made in South Africa towards the discipline and, more broadly, healthcare, peer recognition from clinical doctors remains limited. Participants suggested that a possible reason for this may be due to the stereotype of the medical laboratory disciplines being regarded as unnecessary or unimportant (interviews: P2-P10). As a result, many of these specialists have emigrated to countries such as the United Kingdom and Canada where they feel that their expertise is better valued and recognised by the state healthcare systems.

The sense of devaluing also comes from the public of South Africa for whom histopathologists remain an invisible part of the healthcare chain. This extends to medical students who tend to favour clinical disciplines when choosing areas to specialise in. This impacts the ability to retain and recruit these specialists in South Africa. Evidence from the human resources literature (Mathauer & Imhoff 2006; Phillips & Connel 2006; Rose 2005) indicates that if histopathologists are to be retained in the country, and if the discipline is to attract younger people to it, there needs to be a concerted effort to promote the value of the work to the healthcare chain. This finding is similar to Hale's (2009) argument that despite an increase in the number of new pathologists trained at a national level, the discipline of histopathology in South Africa remains poorly understood by the wider public.

Human capital theory suggests the importance of human resource strategies that exceed financial motivation. The theory stresses that continuous professional development is integral in increasing professional workers' production capacity (Rose 2005; Taylor & Martin 2001). It emphasises the need for large investments in human capital development, whereby the education that workers receive would increase their productivity and efficiency, and motivation, which would result in an economic return of investment for an organisation or society (Marshall 1998; Taylor & Martin 2001). It is believed that it is the human element, and not capital or material resources that determines the success of economic and social development (Rose 2005). Literature suggest that South African doctors, including medical laboratory specialists, emigrate to countries for better opportunities to fulfil their advanced and continuous educational and training needs (Price & Weiner 2005). Whilst these specialists are highly skilled, they still require training and development programmes that update their scientific knowledge (Plebani 2010).

Compulsory public sector service policies by both the South African Department of Health and the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) was also cited as a major factor contributing to the exodus of medical laboratory specialists from South Africa. The NHLS is responsible for the human resources policies of all medical laboratory professionals employed by South Africa. Upon qualifying, histopathologists are compelled to work for the NHLS for two years (interviews: P2, P5, P8, P10). The national policy on medical education requires graduates to provide compulsory service to the NHLS for two years. Pathologists that leave before the completion of their two years of community service are compelled to pay a fine, depending on the number of years remaining for the completion of their service. These fines can range up to R3 million or $300 000. Whilst the intention of the NHLS strategy is to retain histopathologists to service an ailing public sector, the retention is temporary, with many leaving for the private sector or for overseas once the two-year compulsory service is over. According to participants interviewed, there have been cases where the fines have been paid by private sector laboratories, both nationally and internationally, so as to release histopathologists from their contracts. Given the acute shortage of these specialists globally, many private laboratories are willing to pay these fines (Andrea et al. 2009; Bersch 2003; Bersch 2009; Blanckaert 2010; McLane 2010; Michel 2008). This directly relates to the findings of a study conducted by George, Quinlan and Reardon in 2009, which shows that from a survey of 1200 doctors in South Africa in the last year of their community service, over 900 expressed that they intended on working abroad (emigrating) on the completion of their community service, which shows that the compulsory community service measure only retains these doctors temporarily (for the duration of their service). Therefore, whilst working for the NHLS may seem to be an effective retention strategy, it may actually be counterproductive in practice.

Research indicates that South African doctors work under difficult conditions, such as: an ailing public healthcare system, increasing corruption in the public healthcare sector, exposure to infectious sub-Saharan diseases, erosion of professional status of doctors, and political and economic uncertainty. These factors influence doctors to emigrate to countries with a safer and lower-risk working environment (Pillay 2007).

Whilst emigration of South African doctors for socioeconomic reasons is not a new phenomenon, the types of socio-economic reasons influencing emigration has changed. For example, most doctors emigrated pre-1994 in opposition to the Apartheid state (Arnold & Lewinsohn 2010); however, post 1994, large numbers of mainly white doctors have migrated for a host of personal and professional reasons (Lynellyn 2007). Many white South African doctors felt that after 1994 they were treated unfairly regarding job opportunities and remuneration due to the introduction of affirmative action, which aimed to remove the labour market injustices of apartheid and to reverse the discrimination, thus allowing for fair discrimination to advance the position of previously marginalised groups (mainly Africans) (Lynellyn 2007). Since 1994, 37% of the country's doctors have emigrated to more-developed countries (Naicker et al. 2009). A substantial number of health professionals have also emigrated due to their belief that the standard of education provided for their children in South Africa was below international norms in developed countries. As a result, they have emigrated to countries where they have felt that their children would receive higher standards of education (Adepoju 2006). In addition, they have also emigrated due to concerns about the future employability of their children. Compounding this perception is the high unemployment rate of over 25% in South Africa (unofficially this rate is pitched at 40%). The high unemployment rates contribute to high rates of inequality, which fuel social unrest and uncertainty. South Africa is accused of being unable to develop jobs fast enough to cater for the strikingly fast-growing young population (Adepoju 2006). A general sense of an unpredictable future for middle-class professionals, such as doctors and specialist doctors, emerged from this study as a factor influencing the decision to leave South Africa.

The national and international literature on socio-economic and political factors contributing as catalysts for global migration is extensive (Allsop et al. 2009; Chiswick 2011; Clark et al. 2006; Downey 2010; Hamilton 2004; Khoo et al. 2007; Martin 2005; Michel 2008; Narasimhan et al. 2004; WHO 2010; Papoutsakis 2010). In this regard, the present study's findings were supported by the extant literature.

Another reason cited by participants for emigration was the burgeoning rate of crime. Endemic rates of crime emerged as an important subtheme of broader socio-economic factors influencing histopathologists to emigrate out of South Africa. South Africa has one of the highest crime rates of any country that is not at war. Increasingly, crime is occurring in hospitals, especially in the public sector; there have been cases of rapes, murders and hijackings of doctors in their workplaces or en-route to their workplaces. The role that crime plays in the retention of South African skilled workers in general was emphasised by Pillay's (2007) work, which showed that crime was the main factor responsible for the emigration of higher and middle class white and Indian populations (which are the two races that constitute the highest number of doctors in South Africa). He added that generally speaking, over 96% of emigrants from South Africa have cited crime as their main reason for leaving the country. Adepoju (2006) supported this argument in his research, which showed that social issues such as abject poverty and crime in South Africa are push factors that are more compelling in the emigration of South Africa healthcare professionals than pull factors such as better living conditions that can be met abroad.

Conclusion

The main strength of the study is that it begins a scholarly discussion of histopathologists, their professional milieu and their importance in the healthcare chain. Therefore, the study contributes to closing the gap in the literature on non-clinical doctors such as histopathologists. It also secured a relatively high participation rate. It has identified a range of themes that may influence histopathologists to emigrate. These themes have little to do with remuneration, which is often cited as the main reason for emigration. As public health policy continues to evolve in South Africa, the findings of this and similar studies can provide an evidence-based rationale to inform retention strategies for these specialist doctors.

However, the present study has some limitations, which need to be taken into account. First, the findings are suggestive rather than conclusive, given the nature of the research design and sample size. Therefore, the results were not able to be generalised nationally or beyond the population investigated. A second limitation was that the researchers were not able to obtain official salary scales for histopathologists in the private sector. Private laboratories are highly competitive and this data is understandably viewed as sensitive.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Research Foundation of South Africa for funding the study through grant number 75593. The funding was provided without any input or influence into the research design, data collection, data analysis or influence on whether and where to publish the findings. We would also like to thank AK who transcribed the interviews.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

N.C. and S.R. conceived and designed the study. N.C. collected the data. N.C. and S.R. interpreted the data. N.C. completed the literature review. N.C. and SR drafted the manuscript.

References

Adepoju, A., 2006, Recent trends in international migration in and from Africa, Human Resources Development Centre, Nigeria. [ Links ]

Allsop, J., Bourgeault, I.L., Evetts, J. & Bianic, T.S., 2009, 'Encountering Globalization: Professional Groups in an International Context', Current Sociology 57, 487-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011392109104351 [ Links ]

Andrea, B., Noie, N., Holladay, B. & Bugbee, A., 2009, 'Wage and Vacancy Report: Laboratory Workforce Shortage Reaches Crisis', American Society for Clinical Pathology 40, 133-141. [ Links ]

Arnold, P.C. & Lewinsohn, D.E., 2010, 'Motives for migration of South African doctors to Australia since 1948', Medical Journal of Australia 192, 288-290. [ Links ]

Ashmore, J., 2013, '"Going private": A qualitative comparison of medical specialists' job satisfaction in the public and private sectors of South Africa', Human Resources for Health 11, 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-1 [ Links ]

Awases, M., Gbary, A., Nyoni, J. & Chatora, R., 2004, 'Migration of health professional in six countries: A synthesis report', World Health Organization, Republic of Congo. [ Links ]

Babbie, E.R., 2011, The Basics of Social Research, Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, CA. [ Links ]

Bates, I. & Maitland, K., 2006, 'Are Laboratory Services coming of Age in Sub-Saharan Africa?', Clinical Infectious Diseases 42, 383-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/499368 [ Links ]

Beckering, R. & Brunner, R., 2003, 'The lab shortages crisis: A practical approach', viewed 03 April 2011, from www.mlo.com [ Links ]

Bersch, C., 2003, Combination of demands sharpens pinch of personnel shortage, medical Laboratory Observor 35 (4), 52-53. [ Links ]

Bersch, C. 2009, 'The "globalization" of the medical lab', Going Global [Online], viewed 13 May 2011, from www.mlo.com [ Links ]

Blanckaert, N., 2010, 'Clinical pathology services: Remapping our strategic itinerary', Clinical Chemical Laboratory Medicine 48, 9, 19-925. [ Links ]

Bonner, A., 2003, 'Recognition of expertise: an important concept in the acquisition of nephrology nursing expertise', Nursing & health sciences 5, 123-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00143.x [ Links ]

Bourgain, A., Pieretti, P. & Zou, B., 2008, The Shortage of Medical Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa and Substitution Policy, Bielefeld University, Bielefeld, Germany. [ Links ]

Braun,C. &Clarke,V., 2006, 'UsingThematicAnalysisinPsychology', QualitativeResearch in Psychology 3, 77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Brier, M. & Wildschut, A., 2006, Doctors in a Divided Society: The Profession and Education of Medical Practitioners in South Africa, HSRC Press, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Chikanda, A., 2006, 'Skilled Health Professionals' Migration and Its Impact on Health Delivery in Zimbabwe', Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32, 667-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691830600610064 [ Links ]

Chiswick, B.R., 2011, High-Skilled Immigration in a Global Labour Market, AEI Press, Washington DC. [ Links ]

Clark, P.F., Stewart, J.B. & Clark, D.A., 2006, 'The globalization of the labour market for health-care professionals', International Labour Review 145, 37-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2006.tb00009.x [ Links ]

Collins, J.L., 2002, 'Mapping Global Labour Market: Gender and Skill in the Globalizing Garment Industry', Gender & Society 16, 921-940. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089124302237895 [ Links ]

De Villiers, M. & De Villiers, P., 2004, 'Doctors' views of working conditions in rural hospitals in the Western Cape', South African Family Practice 46, 21-26. [ Links ]

Downey, A., 2010, 'The impact of an aging population on global healthcare', Issues Monitor 4, 1-12. [ Links ]

Erasmus, J. & Hall. E., 2003, 'The international mobility of health professionals: An evaluation and analysis based on the case of South Africa', Trends in International Migration, OECD, Paris. [ Links ]

Ferrinho, P., Lerberghe, W., Fronteira, I., Hipolito, F. & Biscaia, A., 2004, 'Dual practice in the health sector: Review of the evidence', Hum Resour Heal 2, 14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/CCLM.2006.168 [ Links ]

George, G., Quinlan, T. & Reardon, C., 2009, Human resources for health: A needs and gaps analysis of HRH in South Africa, Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division (HEARD), South Africa. [ Links ]

Guidi, G.C. & Lippi, G., 2006, 'Laboratory medicine in the 2000s: Programmed death or rebirth?', Clinical Chemical Laboratory Medicine 44, 913-917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/CCLM.2006.168 [ Links ]

Hagopian, A., Thompson, M.J., Fordyce, M. & Johnson, K., 2004, 'The migration of physicians from sub-Saharan South Africa to the United States of America: Measures of the African brain drain', Human Resources for Health 2, 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-2-17 [ Links ]

Hale, M.J., 2009, 'Anatomical pathology in South Africa: Developments, challenges and opportunities', The Bulletin of the Royal College of Pathologists 147, 241-242. [ Links ]

Hamilton, K.Y.J., 2004, 'The Global Tug-of-War for Health Care Workers', Migration Information Source, viewed 16 November 2013, from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/global-tug-war-health-care-workers [ Links ]

Health Professionals Council of South Africa, 2011, 'Labour Market Statistics for the HPCSA', in HPCSA (ed.), HPCSA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

HPCSA, Health Professions Council of South Africa, 2011, 'Where Have All our Practitioners Gone?', The Bulletin. [ Links ]

Horowitz, C.R., Suchman, A.L., Branch, W.T. & Frankel, R.M., 2003, 'What do doctors find meaningful about their work?', Annals of Internal Medicine 138, 772-775. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-9-200305060-00028 [ Links ]

Independent Online (IOL), 2009, Frustrated Doctors Strike: South Africa. [ Links ]

Humphrey, C. & Russell, J., 2004, 'Motivation and values of hospital consultants in South-East England who work in the National Health Service and do private practice', Social Science and Medicine 59, 1241-1250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/'.socscimed.2003.12.019 [ Links ]

Khoo, S., Mcdonald, P. & Hugo, G., 2007, 'A Global Labor Market: Factors Motivating the Sponsorship and Temporary Migration of Skilled Workers to Australia, International Migration Review 41, 489-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00076.x [ Links ]

Lu, H., While, A. & Barriball, K., 2005, 'Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature review', International Journal of Nursing Studies 42, 211-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.003 [ Links ]

Lynellyn, D., 2007, Facilitation of the recruitment and placement of foreign health care professionals to work in the public sector health care in South Africa, International Organization for Migration, South Africa. [ Links ]

Marshall, G., 1998, 'Human Capital Theory', A Dictionary of Sociology, viewed 15 November 2013, from http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O88-Humancapitaltheory.html [ Links ]

Marshall, M. & Harrison, S., 2005, 'It's about more than money: Financial incentives and internal motivation', Quality and Safety in Health Care 14, 4-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.013193 [ Links ]

Martin, P., 2005, Migrants in the global labour market, Global Commision on International Migration, Geneva. [ Links ]

Mathauer, I. & Imhoff, I., 2006, 'Health worker motivation in Africa: The role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools', Human Resources for Health 4, 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-4-24 [ Links ]

Mclane, M., 2010, 'Do one thing to promote the lab profession', viewed 15 November 2013, from http://www.mlo-online.com/articles/201002/do-one-thing-to-promote-the-lab-profession.php [ Links ]

Michel, R., 2008, New insights on the globalization of healthcare and laboratory testing, viewed 11 November 2013, from http://www.darkdaily.com/new-insights-on-the-globalization-of-healthcare-and-laboratory-testing#axzz3ARiPx2hT [ Links ]

Naicker, S., Plange-Rhule, J., Tutt, R.C. & Eastwood, J.B., 2009, 'Shortage of Healthcare Workers in Developing Countries: Africa', Ethnicity and Disease 19, 60-64. [ Links ]

Narasimhan, V., Brown, H., Pablos-Mendez, A., Adams, O., Dussault, G., Elzinga, G., Nordstrom, A. et al., 2004, 'Responding to the global human resources crisis', Lancet 363, 1469-1472. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16108-4 [ Links ]

Papoutsakis, H., 2010, 'Towards a Global Labor Market in a Knowldedge-Dominated Economy', Journal of Knowledge Management Practice 11, 1-8. [ Links ]

Petti, C.A., Polage, C.R., Quinn, T.C., Ronald, A.R. & Sande, M.A., 2005, Laboratory Medicine in Africa: A barrier to Effective Health Care, University of Manitoba, Canada. [ Links ]

Phillips, J.J. & Connel, A.O, 2006, Managing Employee Retention: A Strategic Accountability Approach, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

Pillay, R., 2007, 'A conceptual framework for the strategic analysis and management of the brain drain of African health care professionals', African Journal of Business Management 1, 026-03. [ Links ]

Pillay, R., 2009, 'Work satisfaction of professional nurses in South Africa: A comparative analysis of the public and private sectors', Human Resources for Health 7, 15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-15 [ Links ]

Plebani, M.L.G., 2010, 'Is laboratory medicine a dying profession? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believed', Clinical Biochemistry 43, 939-941. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.05.015 [ Links ]

Price, M. & Weiner, R., 2005, 'Where have all the doctors gone? Career choices of Wits medical graduates', South African Medical Journal 95, 414-419. [ Links ]

Roenen, C., Ferrinho, P., Van Dormael, M., Conceicao, M. & Van Lerberghe, W., 1997, 'How African doctors make ends meet: an exploration', Trop Med Int Health 2, 127-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-240.x [ Links ]

Rogerson, C.M., 2007, 'Medical recruits: The temptation of South African health care professionals', Migration Policy Series: Southern African Migration Project, Kingston. [ Links ]

Rose, N., 2005, 'Human Relations Theory and People Management', European Management Journal 34, 43-62. [ Links ]

Ruggunan, S., 2013, 'Labour Process and Professional Status: An Exploratory Case Study of Histopathologists in Kwazulu-Natal', South African Review of Sociology 44, 98-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2013.802541 [ Links ]

Tanyanyiwa, D.M., 2010, 'Cost Challenges for Laboratory Medicine Automation in Africa', PanAfrican Medical Journal 22, 1-11. [ Links ]

Taylor, J.E. & Martin P.L., 2001, 'Human Capital: Migration and Rural Population Change', Handbook of Agricultural Economics, Elsevier, New York. [ Links ]

The South African, 2010, 'Medical brain drain is hurting KZN', viewed 11 November 2013, from http://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/medical-brain-drain-is-hurting-kzn.htm [ Links ]

Vujici, M., Zurn, P., Diallo, K., Adams, O. & Dal Poz, M.R., 2004, 'The role of wages in the migration of health care professionals from developing countries', Human Resources for Health 2, 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478^491-2-1 [ Links ]

Wildschut, A., 2010, 'Doctors in the public service: too few for too many', viewed 19 April 2011, from http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-outputs/view/5269 [ Links ]

World Health Organization, 2010, 'International Migration of Health Workers: Improving International Co-operation to Address the Global Health Workforce Crisis', viewed 11 November 2013, from http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/oecd-who_policy_brief_en.pdf [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Shaun Ruggunan

Private Bag X54001

Durban 4000

South Africa

Email:ruggunans@ukzn.ac.za

Received: 10 Jan. 2014

Accepted: 20 June 2014

Published: 06 Nov. 2014