Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

On-line version ISSN 2071-9736

Print version ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.19 n.1 Cape Town Jan. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v19i1.762

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The psychological experience of women who survived HELLP syndrome in Cape Town, South Africa

Rizwana Roomaney; Michelle G. Andipatin; Anika Naidoo

Department of Psychology, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count (HELLP syndrome) is a high-risk pregnancy condition that could be fatal to mother and / or baby. It is characterised, as the acronym indicates, by haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low blood platelets.

OBJECTIVE: This study explored women in Cape Town's psychological experience of HELLP syndrome.

METHOD: Six participants who previously experienced HELLP syndrome were interviewed. Using a grounded theory approach, themes emerged and a model illlustrating the psychological experience of HELLP syndrome was constructed.

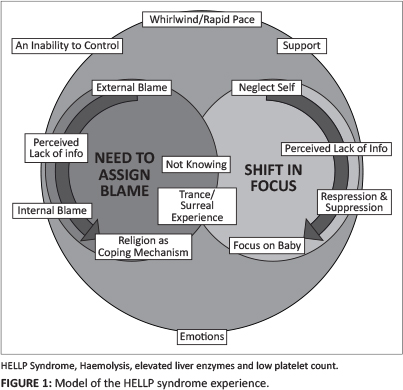

RESULTS: The major themes that emerged were the perceived lack of information, a need to assign blame and a shift in focus. Themes of not knowing and trance and/or surreal experience underpin the cognitive aspects of the HELLP syndrome experience. Themes that expressed feelings of an inability to control, whirlwind and/or rapid pace and support acted together to bind the experience. Finally, emotions such as anger, ambivalence, disbelief, anxiety, guilt, loneliness and fear were present throughout the experience.

CONCLUSION: This study developed an initial exploratory model representing the psychological experience of HELLP syndrome in a sample of South African women. Underlying this entire experience was a perceived lack of information which had a profound effect on numerous aspects of the experience ranging from where to locate blame to the varied emotions experienced.

ABSTRAKTE

AGTERGROND: Die HELLP sindroom is 'n hoë-risiko swangerskap toestand wat kan dodelik vir moeder en/of baba wees. Dit word gekenmerk deur hemolise, verhoogde lewerensieme en lae bloedplaatjies.

DOELWIT: Hierdie studie het Suid-Afrikaanse vroue se sielkundige ervaring van die HELLP sindroom ondersoek.

METODE: Ses deelnemers wat voorheen HELLP sindroom ervaar het is ondervra. Met die gebuik van gefundeerde teorie as 'n teoretiese raamwerk en ontleding het temas na vore gekom en 'n model wat die sielkundige ervaring van HELLP sindroom illustreer, is gebou.

RESULTATE: Die vernaamste temas wat na vore gekom het was die oënskynlike gebrek aan inligting, 'n behoefte om skuld toe te skryf en 'n verskuiwing in fokus. Die tema van nie weet en beswyming en/of surrealistiese ervaring ondersteun die kognitiewe aspekte van die HELLP sindroom. Temas wat gevoelens van geen beheer, warrelwind en/of vinnige tempo en ondersteuning uitgesprek het, het saam opgetree om die ervaring te bind. Ten slotte, emosies soos woede, teenstrydigheid, ongeloof, angs, skuldgevoelens, eensaamheid en vrees was teenwoordig in die hele ervaring.

GEVOLGTREKKING: Hierdie studie het van'n aanvanklike ondersoekende model van die sielkundige ervaring van HELLP sindroom tot 'n steekproef van die Suid-Afrikaanse vroue ontwikkel. Onderliggend aan hierdie hele ervaring was 'n oënskynlike gebrek aan inligting wat 'n diepgaande uitwerking gehad het op talle aspekte van die ervaring wat gewissel het van waar om die blaam te plaas tot die uiteenlopende ervaarde emosies.

Introduction

Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count (HELLP syndrome) is a high-risk condition of pregnancy with potentially fatal outcomes for mother and baby. It is typically identified by the presence of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low blood platelets (Curtin & Weinstein 1999). These symptoms put the mother at risk for complications such as liver haemorrhage and rupture, renal failure and stroke; and the baby at risk based on complications resulting from premature delivery (Hagl-Fenton 2008).

The only way to reverse the symptoms associated with HELLP syndrome and prevent possible infant mortality is through emergency delivery of the baby (Dildy & Belfort 2010). Because of its potentially life-threatening nature it also has a profound effect on the emotional status of women experiencing it (Kidner & Flanders-Stepans 2004). In South Africa, it was reported that HELLP syndrome resulted in 70 maternal deaths between 2002 and 2004 and 54 maternal deaths between 2005 and 2007 (National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths 2006; 2007). The latest report indicates 86 maternal deaths as a result of HELLP syndrome between 2008 and 2010 (Health Systems Trust 2012). The latest increase in maternal deaths because of HELLP syndrome warrants this study.

Research relating to HELLP syndrome has focused primarily on medical and clinical issues pertaining to the disease. Currently, only one international study on the psychological experiences of HELLP syndrome (Kidner & Flanders-Stepans 2004) has been published and this research was conducted in a first-world country. It was therefore considered necessary to conduct a local study of the psychological experiences of HELLP syndrome within the South African context, specifically at primary healthcare institutions. This information will allow medical professionals to gain an understanding with regard to the HELLP syndrome experience. For the purpose of this study the psychological experience referred to the thoughts, feelings and emotions experienced by women who have survived HELLP syndrome. This study employed grounded theory in order to construct a model of the HELLP syndrome experience.

Background

HELLP syndrome is considered to be a variation of pre-eclampsia which is associated with a high degree of maternal and perinatal morbidity (Dildy & Belfort 2010). The disease requires aggressive treatment aimed at stabilising the mother and delivery of the baby in order to prevent maternal and/or neonatal morbidity (Habli & Sibai 2008).

The vast majority of research associated with HELLP syndrome related to, among others, clinical aspects such as aetiology, incidence, prevalence, medical case studies, recurrence, maternal and neonatal outcomes and management and treatment of the illness (Barnett & Kendrick 2010; Rajab, Skerman & Issa 2002; Weinstein 1985).

Kidner and Flanders-Stepans (2004) were the first to conduct a study relating to the psychological experience of HELLP syndrome. The researchers interviewed nine mothers who experienced HELLP Syndrome in the United States of America and developed a model of their experience. This model produced themes of premonition, symptoms, a feeling of betrayal, a 'whirlwind' experience and loss. Their research also highlighted the emotional experience with common emotions described being such as fear of death, frustration, anger and guilt. In addition, a sense of having no control and not knowing bounded the entire experience.

Since HELLP syndrome is a high-risk condition of pregnancy, literature related to high-risk pregnancy was reviewed in order to provide insight into the psychological experience. Key areas emerged including, among others, stressors, coping mechanisms, support, satisfaction regarding healthcare decisions and feelings and emotions.

Many stressors impact on the experience of high-risk pregnancy. One stressor is a loss of control of regular functioning and duties experienced by women who are hospitalised because of high-risk pregnancies (Richter, Parkes & Chaw-Kant 2007). The experience of high-risk pregnancy may foster a sense of helplessness and lack of control, especially in the case of HELLP syndrome where the symptoms appear to cascade, with women being unable to control the experience (Van Pampus et al. 2004). A wide range of emotions has also been associated with hospitalisation as a result of high-risk pregnancy. These emotions include anger, frustration, loss and loneliness, fear and anxiety, hope and ambivalence (Leichtentritt et al. 2005). Women experiencing high-risk pregnancies have also reported feelings of isolation and helplessness (Price et al. 2007; Richter et al. 2007).

Support therefore plays a significant role in terms of helping women to cope with their circumstances (Corbet-Owen 2003; Layne 2006). It is also imperative that women be referred for psychological assistance in order to deal with high-risk pregnancy experiences (Poel, Swinkel & De Fries 2009).

Given the reported distress that women experience, coping mechanisms play a crucial role in mediating the high-risk pregnancy experience. According to Yali and Lobel (1999), women experiencing high-risk pregnancies may adopt either avoidant (maladaptive) coping mechanisms or positive appraisal in order to cope. Prayer and positive appraisals were employed frequently as positive coping strategies during high-risk pregnancy (Yali & Lobel 1999). Furthermore, women with a more optimistic disposition tend to use more positive appraisals and tend to view their high-risk pregnancy as more controllable, thus leading to lower distress (Lobel et al. 2002). In addition, spirituality has been utilised as a coping mechanism in dealing with the stress of high-risk pregnancy by calming the fears and anxieties of women experiencing high-risk pregnancy (Price et al. 2007)

Satisfaction with involvement in healthcare decisions during a high-risk pregnancy has become an important aspect when dealing with high-risk experiences. Two trends in decision making have been identified. Whilst most women prefer to be involved actively in decision making, others prefer to rely on the knowledge and expertise of the healthcare professionals (Harrison et al. 2003). When the type of involvement the women wanted was congruent with what they experienced, the women were satisfied, but when the type of involvement the women wanted was not what they experienced, they were dissatisfied (Harrison et al. 2003).

The literature discussed above demonstrates that a number of factors play a role in the way in which women experience high-risk pregnancy.

Problem statement

Both current and prior research on HELLP syndrome is focused on medical aspects of the condition and the psychological experiences are widely unexplored. Research on pregnancy and childbirth needs to be cognisant of the healthcare system. Despite all measures taken within South Africa to redress past imbalances, the healthcare system is still deeply divided along racial, class and economic lines (Cooper et al. 2004). This translates into a lack of resources resulting in basic treatment focused on treating the patient medically, whilst the psychological experiences cannot be fore-grounded. Thus, the gap within this body of scholarship and practice necessitates research of this nature.

Aims of the study

The aim of this study was to gain an in-depth understanding of the psychological experiences of women who experienced HELLP syndrome. For the purpose of this study, psychological experiences were defined as thoughts, feelings and emotions.

Research objectives

To gain an in-depth understanding of the maternal experience of HELLP syndrome, utilising grounded theory in order to develop a model.

Theoretical framework

Grounded theory aims to generate substantive theory from data without being driven by theory (Charmaz 2006). Since this study was the first of its kind in South Africa, the utilisation of grounded theory was appropriate as the aim was to construct an initial, exploratory model for the HELLP syndrome experience.

Research method and design

Design

The study employed a qualitative, explorative and descriptive study design in order to gain deep and rich data for better insight into the women's psychological experience of HELLP syndrome. Grounded theory was utilised as both a theoretical framework and a methodological framework.

Sampling procedure and setting

The researchers worked with a Junior Registrar (a medical doctor undergoing specialist training) to recruit participants through a State hospital. State hospitals generally serve patients from lower- to middle-class socioeconomic backgrounds, however patients from higher socioeconomic backgrounds with HELLP syndrome are also referred to State hospitals because these hospitals are better equipped to deal with HELLP syndrome than doctors in private practice. In addition, the researchers were mindful of overcoming middle-class bias in research and decided that a diverse sample was necessary (Chadwick 2007).

The registrar contacted women who experienced HELLP syndrome at the hospital to enquire as to whether or not they would be willing to participate in the study. The details of those who agreed were forwarded to the researchers who then initiated contact with participants. Gaining access to a specialised sample of HELLP syndrome patients proved especially challenging within the public healthcare system, as the registrar was unable to find a large sample pool of participants who were willing to share their experiences with researchers.

Sample

The sample comprised six women ranging in age from 30 to 44. The sample size was determined at a point where no new themes emerged. The study employed purposive sampling with inclusion criteria specifying that participants should have had experienced HELLP syndrome at least one year prior to the interview process. The participants varied in terms of home language, education, religion, marital status and socioeconomic status (refer to Table 1).

Of the six participants, three were English mother-tongue speakers, one was Afrikaans, one Xhosa speaking and the last spoke Gujarati. The participants varied in terms of education level, ranging from Grade 12 to post-graduate, tertiary-level education. All of the participants were married and none were aware of any underlying medical conditions. With the exception of one participant, the sample had experienced at least one infant loss, not necessarily as a result of HELLP syndrome. Of these losses, however, three were as a direct result of HELLP syndrome. The participants also showed differences in terms of religious background. Three patients were treated in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) post-delivery and all participants had received medical treatment in Cape Town.

Data collection

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews took place in order to allow participants to reflect on their psychological experiences of HELLP syndrome. In keeping with grounded theory, semi-structured interviews were conducted by the authors of the article. All interviews took place in the Psychology department where the researchers were based. The first and third authors conducted the interviews, whilst the second author supervised the session from behind a oneway mirror. The interviewers underwent informal training with a pilot interview and all interviews were supervised by the second author. The participants agreed to this arrangement. All interviews were conducted in English, lasted between 50 and 90 minutes and provided rich data that lent itself to in-depth qualitative analysis. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the interviewers. Interviewers underwent informal training and the interviews were supervised.

Data analysis

Grounded theory is regarded as being one of the hallmarks of qualitative inquiry, developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967) who argued that substantive theory could be generated from data without being driven by theory (Charmaz 2006). The purpose is, therefore, to generate a theory that is faithful to the data. Glaser and Strauss (1967) developed systematic methodological strategies in order to construct theory, thus grounded theory is both a methodology and is used to build models or theory based on data (Henning, Van Rensburg & Smit 2004). These strategies included delaying the literature review and employing a methodology for analysing data and presenting a model that remains true to the data. Grounded theory was used in the present study to analyse the data and build an initial, exploratory model that represented the HELLP syndrome experience in the South African context.

A constant comparative method was utilised, combining a systematic collection of data, coding and analysis in order to generate a theory and model that remained true to the data. Grounded theory analysis commenced with line-by-line coding of data. The researchers worked together to analyse every line of data in order to ensure that consensus was reached with regards to the assigned code and to ensure that the best possible code was assigned to each line of data. Following this, more focused coding took place, generating core categories. The next step in the process was theoretical coding. During this process, the researchers sorted the core categories into themes, examined literature and cross-referenced the categories with the literature. At this stage, possible relationships between categories were explored and specified. The three researchers worked independently during this stage and then compared their respective results. Once the themes and categories were determined, a literature review was conducted. The review was conducted subsequent to the analysis in an attempt to corroborate and re-contextualise the findings of the study and to ensure that the theory and model developed were grounded within the data. Categories that were pervasive and that summarised the fundamental aspects of the HELLP syndrome experience were identified in order to develop a model that depicted the basic emotional and psychological processes involved. Thereafter, factors that shaped those central emotions were pinpointed as well as the strategies that were used for addressing them. The context and the consequences of undertaking those strategies were then examined. Finally, a theoretical model that visually portrayed the interrelationship between experiences was developed. The initial process involved each author working independently at each stage of the analysis. Discussions were held with the three authors at each stage in order to reach a consensus. The in-depth nature of the interviews provided substantively rich data, resulting in the development of an initial, exploratory theory and model.

Reflexivity

The first and third authors were students and the second author supervised the research. At the time of the study, the first and third authors had not experienced pregnancy and child birth. The second author had experienced two pregnancies with HELLP syndrome. The first and third authors' background in psychology allowed them to be empathic toward the experiences of participants, even though they had not experienced pregnancy. This, coupled with the second author's experience of HELLP syndrome, added to the richness of the study.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was granted both by the university and the hospital (UWC REC 06/05/10). Participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the study beforehand, that participation would be voluntary and that they could withdraw from their study at any time without prejudice to their ongoing treatment at the hospital. Participants provided written consent and were assured anonymity and confidentiality. No third parties had access to the tapes or transcripts. Transcripts did not contain the names of participants and pseudonyms were used throughout the process and within this article. Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, each participant received a copy of the consent form with contact numbers of psychologists who could help them deal with any emotions that arose during the interview process. None of the participants took up the offer for additional counselling.

Trustworthiness

Cresswell (2007) has outlined various criteria for evaluating the trustworthiness of grounded theory research. In keeping with his criteria, a number of procedures were incorporated into the study in order to ensure its trustworthiness and credibility. These procedures have been outlined in the methodology section of this article. They include piloting, training and supervision related to the interviews, the method of data coding, analysis, theory development, model construction, and, finally, the reflexivity as outlined above.

Results and discussion

Description of model

Figure 1 is a model representing the psychological experiences of HELLP syndrome in South African women. It comprises two inner interlinking circles that share a common, major theme, namely, perceived lack of information. The first of these two circles represents a major theme depicting the need to assign blame. This theme is expressed using subcategories in order to illustrate the mechanism as to how perceived lack of information affects the need to assign blame. The first theme is that of external blame, as is illustrated when mothers either blame doctors or the nursing staff or the hospital in general. As a result of the perceived lack of information, blame on these external sources becomes difficult to justify, resulting in mothers resorting subsequently to exploring self-blame in order to make sense of the HELLP syndrome experience. Unable to manage the threatening nature of self-blame, mothers then turn to religion as a tool to adopt a fatalistic understanding of their HELLP syndrome experience.

The second inner circle depicts how the perceived lack of information leads to a third major theme, illustrating a shift in focus. Since the mothers did not have sufficient information explaining the experience of HELLP syndrome medically and because of their role as mothers, there was a shift in focus. The mothers whose children survived were cared for in neonatal ICU and those who had miscarriages or stillbirths had to care for their other children at home. The emphasis thus shifted from caring for themselves to caring for their children. The mothers used defence mechanisms of repression and suppression and unconsciously neglect themselves in order to focus on their children.

These circles overlap at the next set of major themes of not knowing and trance and/or surreal experience that underpin the cognitive aspects of the HELLP syndrome experience.

The outermost circle comprises major themes that explore feelings related to whirlwind and/or rapid pace, inability to control and support that bind the entire experience. This is accompanied by emotions such as anger, ambivalence, disbelief, anxiety, guilt, loneliness and fear that were present throughout the experience.

Discussion of major emergent themes Perceived lack of information

Participants reported feeling that they did not receive adequate information from medical staff at the hospital regarding their condition. Some recalled being diagnosed with HELLP syndrome but were unable to comprehend the information relayed to them. Others were not informed of their diagnosis and learnt about it through the researchers or via their own investigations. Some participants only received information when they prompted medical staff and there was a sense of general frustration at the inability to receive answers. It is important to note that this theme was named 'perceived' lack of information. This is significant because it demonstrated that this was the participants' perception and they may in fact have been informed, but unable to process the information:

'Like I said, they didn't explain, they didn't explain anything. It's just that I had the Caesarian and later on I went to the baby. There wasn't any explanation.' (Mischka, 44 years old)

Perceived lack of information was a central theme, as it had an impact on themes such as the need to assign blame and shift in focus. It was also linked to the themes of 'not knowing' and 'inability to control' as well as to the emotions of fear, guilt and anxiety. This theme was linked further to their experience of being in a trance-like state when information was relayed to them.

Similarly, Kidner and Flanders-Stepans (2004) reported frustration relating to lack of information. Some studies have found that a lack of information resulted in increased levels of stress (Wereszczak, Miles & Holditch-Davis 1997), whereas others found that some participants felt no need to have information, citing faith and confidence in their doctors as being sufficient (Harrison 2003). When the amount of information patients desired was what they received, the patients were generally satisfied (Harrison 2003). The current study illustrates incongruence between information desired and that given to patients and hence dissatisfaction with not receiving enough information.

Need to assign blame

The lack of adequate explanations led to an overwhelming need to assign blame in an attempt to make sense of such a devastating experience. Initially, blame was assigned to external sources such as doctors, nurses or other medical staff. This was expressed as negligence or incompetence on the part of healthcare practitioners. One participant blamed her deceased mother because of her understanding that hypertension is hereditary:

'I blamed my mommy, for like giving me this like this em, like the doctor explained to me that hypertension is something that you do inherit. So I blamed her mostly because, now I'm sitting with a problem and she's not here.' (Lucy, 30 years old)

On the contrary, Kidner and Flanders-Stepans' (2004) study revealed that women did not explicitly cast blame but reported feeling betrayed by healthcare providers.

When explanations of external blame no longer sufficed, participants shifted the focus to blaming themselves. Many felt that they contracted the syndrome because of a lack of self-care or working too hard. However, even with the absence of plausible reasons, the self-blame continued.

'Where did I go wrong? That's ... I think that's the hardest part because you're trying to think what you did and what you didn't do.' (Devi, 37 years old)

These sentiments were similar to those expressed in Jackson and Mannix's (2004) study, where mothers reported a tendency to blame themselves for the health of their children, even when it was beyond their control and there was no plausible explanation linking them to the ill health of their offspring.

Self-blame was challenging for participants to live with and religion was then used as a mechanism to assist participants to transcend beyond blaming themselves:

'What has helped me heal was my spiritual side. Knowing that we believe, Hindus firmly believe that the baby takes, your soul takes rebirth. And (um) knowing for that fact (um) like my priest told me, that you must be lucky that your womb was selected, chosen for the soul to pass through ...' (Devi, 37 years old)

Whilst the participants embraced different religions, they all utilised prayer to assist them in making sense of their experiences. Religion seemed to be used as a source of comfort and as a coping mechanism. Because of the lack of control, participants felt that the only positive action they believed they could engage in was prayer. Yali and Lobel (1999) found prayer to be a positive coping strategy. Lobel et al. (2002) further affirmed that when more optimistic mothers used positive appraisals such as prayer, this led to less distress.

The utilisation of religion as a coping mechanism assisted participants to adopt a less-threatening, fatalistic attitude in order to make sense of their experience:

'If they had to pick it up then and do something about it then, maybe my boy could still be alive, or maybe it wasn't meant, it wasn't meant for him to be here.' (Devi, 37 years old)

In conclusion, the need to assign blame is understandable when one has gone through any trauma. Because of the perceived lack of information, the mothers struggled to find a source of blame and made peace with the notion that it was meant to be.

Shift in focus

Since participants had limited understanding of what they had endured physiologically, for those whose babies survived the experience became centred on caring for a premature baby. Since the complications associated with HELLP syndrome in most cases reverse soon after birth, physical recovery for the mother can be relatively quick. Caring, either for their premature babies or other children at home, then became priority. The mothers in this study utilised the defence mechanisms of repression and suppression in order to shift their focus from their own experiences toward their babies in hospital or children at home.

'Every time I look at the baby I think ja you almost weren't there. You know my focus is on her, it's not on what I've experienced ... she's alive and that's it.' (Martelize, 38 years old)

The literature consulted, however, does not explain this shift in focus, probably because most studies explored high-risk pregnancies in general and not HELLP syndrome specifically, but caring for premature babies and the rest of the family has been reported to cause hardships for women (DeVault 1991).

Not knowing

This theme referred to both a general sense of not knowing what was happening to participants at the time and feelings of an inability to control, related to either segments or to the overall experience:

'After the operation I was lying in the ICU. I didn't know what had happened.' (Phumza, 30 years old)

Within both the South African and the American sample, this theme was linked to the theme of 'no control' (Kidner & Flanders-Stepans 2004). However, in the American sample it related more to the rapid pace of events between diagnosis and delivery and within our sample it was rather related to the perceived lack of information and gave rise to emotions such as disbelief, anger, anxiety and fear. An overwhelming sense of uncertainty enveloped participants within the present study, which is indicative of high-risk pregnancies in general. Research indicates that uncertainty during high-risk pregnancy is related to the duration of hospitalisation, with an increase in uncertainty because of the prolonged stay (Clauson 1996).

Trance and/or Surreal experience

Many participants reported that the experience seemed like a bad dream or that they were in a trance-like state. The emotion of disbelief was related strongly to their experience. This theme also related to the themes of 'whirlwind experience/ rapid pace', 'inability to control' and 'passivity':

'... [H]ow I felt going through the folder it was wow this doesn't sound like me. It doesn't sound like this is what I had gone through ... it was like a bad dream.' (Mischka, 44 years old)

Whilst women in the 2004 study by Kidner and Flanders-Stepans reported on their whirlwind experience, this sense of surrealism was not made explicit.

Whirlwind and/or Rapid pace

As a result of the life-threatening nature of the syndrome, medical personnel are compelled to respond swiftly, leaving the mother feeling as though she is merely an observer to her own experience as those with the medical expertise become the active participants. This pace and whirlwind activity often left women in this study feeling powerless and helpless, contributing to their sense of inability to control and not knowing. The whirlwind is likened to a trance-like state or surreal experience, leaving participants feeling alienated from the experience and their bodies:

'Then all of a sudden it's just like everything happened so fast, um, I was in a wheelchair, they were putting drips on me, and they gave like a tranquiliser to make me sleepy and calm.' (Lucy, 30 years old)

Inability to control

Because of the perceived lack of information, a sense of not knowing and the rapid pace of events, participants felt as if they either lacked control or had an inability to control at all. Having no knowledge of HELLP syndrome left participants in the precarious position of being unable to feel any sense of control of the experience and their bodies, rendering them powerless and thereby handing control over to medical experts. This sense of an inability to control resulted in fear and led to emotions such as anxiety, which may have forced participants to accept a passive role. This theme was strongly expressed in the study by Kidner and Flanders-Stepans (2004).

'... [Y]ou have no control coz you know what, you don't know what's going on inside your body.' (Fatima, 32 years old)

Support

The participants in this study received support to help them deal with their experience. Sources of support included husbands and/or partners, immediate family, extended family, in-laws, friends, doctors, nurses and social workers:

'In terms of support, I had a lot of support. I mean the family support that I got was exceptionally good. In fact that, that actually pulled me through psychologically and otherwise and emotionally.' (Mischka, 44 years old)

Wereszczak et al. (1997) found that support acted as a resource and a lack thereof resulted in personal distress. Disruptions in support were experienced as personal stressors. However, Leichtentritt et al. (2005) found that sources of support were a strength for some but a stressor for others. Support played a significant role for participants in this study, as also seen in previous research (Corbet-Owen 2003; Layne 2006).

In addition to the above themes that define the HELLP syndrome experience, a plethora of emotions also surfaced and were present throughout the experience.

Emotions

The most dominant emotions experienced were anger, ambivalence, disbelief, anxiety, guilt, loneliness and fear.

Anger: Anger was not expressed by everybody and when it was, the reasons were varied. One participant expressed immense anger and frustration at the way she was treated. The anger was directed toward the hospital in general and this was because she lost her son and almost her own life as she suffered from multiple organ failure. Other participants may not have expressed anger as explicitly, but may well have had some underlying anger following their experience:

'Oh I was angry. I was really angry. I was like now are they hiding something from me, or did I do something that they didn't want to, there's too many emotional things that goes through your mind.' (Devi, 37 years old)

Leichtentritt et al. (2005) found that anger was because of hospitalisation and the loss of normal life. Participants in both Kidner and Flanders-Stepans' (2004) and our study expressed anger toward medical practitioners. However, the American sample also felt angry toward their own bodies, as they felt betrayed by them; this anger was not expressed in the South African sample.

Guilt: Guilt was linked most commonly to self-blame. Participants felt guilty for a number of reasons, such as being overweight, starting families too late, falling pregnant, working too hard and neglecting themselves and their bodies. This guilt may have been caused by the perceived lack of information. Without knowledge related to the causes of the syndrome, participants blamed themselves for developing HELLP syndrome, often speculating as to how they may have set the disease in motion:

'The guilt was related to my weight because I had in my mind my own diagnosis. I was overweight, still am. My eating habits ... the fact that I didn't want to listen. The doctor was talking nonsense. I didn't want to lie down.' (Martelize, 38 years old)

These findings were different to those in the study by Kidner and Flanders-Stepans (2004), where guilt was experienced in relation to the loss of the baby or not being physically strong enough to care for their babies once they were born.

Ambivalence: Ambivalent feelings generally emerged when participants were trying to make sense of their experience and tried to locate blame. Sources of blame vacillated between external sources, self-blame and fatalism:

'I don't know if I must be, if I must blast my gynae or if I must be eternally grateful that he didn't educate me of such . you know.' (Martelize, 38 years old)

Research indicates that ambivalence does occur during high-risk pregnancy but that this is related to wanting the baby delivered and wanting to prolong the pregnancy for the foetus's sake (Leichtentritt et al. 2005).

Ambivalence was present both throughout the experience and afterwards. Leichtentritt et al. (2005) reported that ambivalence within the high-risk context was related to premature versus delayed delivery of the foetus. However, in our study, ambivalence emerged when participants were trying to locate the source(s) of blame.

Isolation and/or loneliness: Hospitalisation seemed to evoke feelings of loneliness and isolation for many. The isolation was mainly as a result of being in ICU or because of problems in communicating because of their being on a ventilator. Those whose babies survived generally saw their babies for the first time a few days after birth. Isolation is a common experience in those being hospitalised (Leichtentritt et al. 2005).

Fear: Participants expressed an overwhelming fear of losing their babies. The baby's life seemed to take precedence over that of the mothers. This theme was linked to the themes of 'not knowing', 'inability to control' and 'perceived lack of information'. Research indicates that fear during birth does occur, but that this fear is usually related to dying (Leichtentritt et al. 2005). Within the study by Kidner and Flanders-Stepans (2004), participants felt fear regarding their own loss of life and that of their babies, whereas in the present study the fear was more related to losing the babies.

Anxiety: Because of the rapid pace, the inability to control the situation and the perceived lack of information, participants expressed that they felt extremely anxious during their experience. Feelings of an inability to control fed their anxiety, which the women expressed in relation to themselves and their babies. These findings were different from those of Leichtentritt et al. (2005), in which participants expressed anxiety as a result of finances and interpersonal relationships.

Disbelief: Participants initially reacted to the diagnosis with disbelief. This disbelief was not related to a lack of faith in healthcare practitioners, but rather to optimistic bias. Disbelief was also expressed when participants recalled seeing their premature babies for the first time because of their small size and the medical equipment attached to them:

'He said this is what you've got, it's either you or your child and then it was this absolute shock and I thought ooh God now I've buggered up here you know. And still I took my time, I still didn't believe him though you know because I wasn't in pain.' (Martelize, 38 years old)

These sentiments were echoed in the study conducted by Wereszczak et al. (1997), when mothers saw their babies for the first time and experienced total disbelief at their small size and the machines surrounding them.

Passivity: Some participants actively sought information and expressed a need to have some form of control during the experience, whereas others preferred to take on a more passive role. This passivity may have been as a result of absolute faith in doctors or because, unconsciously, the responsibility may have been too great and this may explain why some people prefer being passive (Harrison et al. 2003). Passivity was linked to the rapid pace of events and also related to fatalism when participants gained acceptance of their HELLP syndrome experience.

Gratitude: Retrospectively, the participants relayed feelings of gratitude, either for their own survival, their baby's survival, or both. One of the participants who lost her baby was grateful for the opportunity that she was given to bond with her child prior to its death. Other participants expressed gratitude for the support they received. Gratitude is not usually associated with high-risk pregnancy. Although Kidner and Flanders-Stepans (2004) asked participants about the most positive aspect of their experience, they either failed to elicit or did not report it.

Limitations of the study

Participants had difficulty in articulating their psychological experiences. This may have been for two reasons. Firstly, most participants reported that after the experience, circumstances required that they carried on with their lives and they did not think about their ordeal. Secondly, some participants struggled to identify and label their emotions as this was not part of their socialisation.

In addition, the rather modest sample size may be viewed as a limitation of the study. However, no new information emerged during the latter interviews and this was interpreted as saturation. Small sample sizes have also been noted to be acceptable in cases where the sample population is rather small and specialised (Baker & Edwards 2012), as was the case with this study. It is also important to note that whilst the sample size may have been small, the in-depth nature of the interviews provided thick data, enabling a theory and model to be developed.

Recommendations

Participants received very little information regarding the syndrome. The researchers therefore suggest that medical personnel dealing with pregnancy provide information regarding high-risk pregnancy (in general) and HELLP syndrome (in particular), to pregnant women during consultation. One participant stated that she would like doctors to include problems that may occur during pregnancy and childbirth as part of their birth plan, in order for women to be better prepared in dealing with these challenges, should they occur. Based on the findings of this study, the researchers recommend that doctors debrief women who experience HELLP syndrome in order to provide them with information that may help them to make sense of the experience.

Whilst the primary focus of medicine is on the physical aspects of HELLP syndrome, medical personnel need to be attentive to the psychological needs of patients and provide the necessary debriefing and referrals, where necessary.

This was the first study relating to the psychological aspects of HELLP syndrome in South Africa and more research is required if we are to establish a health system that is responsive to the needs of all women.

Conclusion

HELLP syndrome represents one of the most devastating conditions of pregnancy. This study was an attempt to explore the maternal emotional experiences that would aid medical personnel in dealing with mothers in a more empathic way. This was the first study exploring the psychological experience of women who experienced HELLP syndrome in the South African context and was therefore exploratory in nature.

An initial exploratory and descriptive model was developed which represented the psychological experience of HELLP syndrome in a sample of South African women. Underlying this entire experience was a perceived lack of information, which had a profound effect on numerous aspects of the experience ranging from where to locate blame to the varied emotions experienced.

Acknowledgements

This project received financial assistance from the University of the Western Cape.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

R.R. (University of the Western Cape) conducted the interviews, analysed the data and was responsible for writing the manuscript. A.N. (University of the Western Cape) conducted the interviews and analysed the data. M.G.A. (University of the Western Cape) conceptualised the study, supervised the interviews, analysed the data and assisted in writing the manuscript.

References

Baker, S.E. & Edwards, R., 2012, How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research, National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper, viewed 27 June 2013, from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.Uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf [ Links ]

Barnett, R. & Kendrick, B., 2010, 'HELLP syndrome - a case study, New Zealand Journal of Medical Laboratory Science 64(1), 14-17. [ Links ]

Chadwick, R., 2007, 'Paradoxical subjects - women telling birth stories', doctoral thesis, Department of Psychology, University Cape Town. [ Links ]

Charmaz, K., 2006, Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis, Sage Publications Ltd., London. [ Links ]

Clauson, M.I., 1996, 'Uncertainty and stress in women hospitalized with high-risk pregnancy', Clinical Nursing Research 5(3), 309-325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/105477389600500306 [ Links ]

Cooper, D., Morroni, C., Orner, P., Moodley, J., Harries, J., Cullingworth, L. et al., 2004, 'Ten years of democracy in South Africa: Documenting transformation in reproductive health policy and status', Reproductive Health Matters 12(24), 7085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24143-X [ Links ]

Corbet-Owen, C., 2003, 'Women's perceptions of partner support in the context of pregnancy loss(es)', South African Journal of Psychology 33(1), 19-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124630303300103 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2007, Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [ Links ]

Curtin, W.M. & Weinstein, L., 1999, 'A review of HELLP syndrome', Journal of Perinatology 19(2), 138-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7200165 [ Links ]

DeVault, M.L., 1991, Feeding the family: The social organization of caring as gendered work, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Dildy, G.A. & Belfort, M.A., 2010, 'Complications of pre-eclampsia', in M.A. Belfort, G. Saade, M.R. Foley, J. Phelan & G.A. Dildy (eds.), Critical Care Obstetrics, 5th edn., pp. 438-465, Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex. [ Links ]

Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L., 1967, The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research, Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago. [ Links ]

Habli, M. & Sibai, B.M., 2008, 'Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy', in R.S. Gibbs, B.Y. Karlan, A.F. Haney & I.E. Nygaard (eds.), Danforth's Obstetrics and Gynecology, 10th edn., pp. 257-275, Lippincott Willaims & Wilkins, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Hagl-Fenton, D.J., 2008, 'Beyond preeclampsia: HELLP syndrome', RN 71(3), 22-25. [ Links ]

Harrison, M.J., Kushner, K.E., Benzies, K., Rempel, G. & Kimak, C., 2003, 'Women's satisfaction with their involvement in health care decisions during a high-risk pregnancy', Birth 30(2), 109-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2003.00229.x [ Links ]

Health Systems Trust, 2012, Saving mothers 2008-2010: Fifth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa, National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, viewed 08 June 2014, from http://www.hst.org.za/print/publications/saving-mothers-2008-2010-fifth-report-confidential-enquiries-maternal-deaths-south-afri [ Links ]

Henning, E., Van Rensburg, W. & Smit, B., 2004, Finding your way in qualitative research, Van Schaik, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Jackson, D. & Mannix, J., 2004, 'Giving voice to the burden of blame: A feminist study of mothers' experiences of mother blaming', International Journal of Nursing Practice 10(4), 150-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2004.00474.x [ Links ]

Kidner, M.C. & Flanders-Stepans, M.B., 2004, 'A Model for HELLP syndrome: The maternal experience', Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 33(1), 44-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0884217503261131 [ Links ]

Layne, L.L., 2006, 'Pregnancy and infant loss support: A new, feminist, American, patient movement?', Social Science & Medicine 62(3), 602-613. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.019 [ Links ]

Leichtentritt, R.D., Blumenthal, N., Elyassi, A. & Rotmensch, S., 2005, 'High-risk pregnancy and hospitalization: The women's voices', Health & Social Work 30(1), 39-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hsw/30.L39 [ Links ]

Lobel, M., Yali, A.M., Zhu, W., De Vincent, C. & Meyer, B., 2002, 'Beneficial associations between optimistic disposition and emotional distress in high-risk pregnancy', Psychology & Health 17(1), 77-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440290001548 [ Links ]

National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, 2006, Saving mothers 2002-2004: Third report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa, Department of Health, Pretoria. [ Links ]

National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, 2007, Saving mothers 2005-2007: Fourth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in South Africa, viewed 08 June 2014, from http://www0.sun.ac.za/ruralhealth/ukwandahome/rudasaresources2009/DOH/savingmothers%2005-07%5B1%5D.pdf [ Links ]

Poel, Y.H., Swinkel, P. & De Fries, J.I., 2009, 'Psychological treatment of women with psychological complaints after preeclampsia', Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynaecology 30(1), 65-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01674820802545990 [ Links ]

Price, S., Lake, M., Breen, G., Carson, G., Quinn, C. & O'Connor, T., 2007, 'The spiritual experience of high-risk pregnancy', Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 30(1), 63-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00110.x [ Links ]

Rajab, K.E., Skerman, J.H. & Issa, A.A., 2002, 'HELLP syndrome: Incidence and management', Bahrain Medical Bulletin 24(4), 11 pages. [ Links ]

Richter, M.S., Parkes, C. & Chaw-Kant, J., 2007, 'Listening to the voices of hospitalized high-risk antepartum patient', Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 36(4), 313-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00159.x [ Links ]

Van Pampus, M.G., Wolf, H., Weimar Shultz, W.C., Neeleman, J. & Aarnoudse, J.G., 2004, 'Posttraumatic stress disorder following preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome', Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetric Gynaecology 25(3-4), 183-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01674820400017863 [ Links ]

Weinstein, L., 1985, 'Preeclampsia/eclampsia with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and thrombocytopenia', Obstetrics and Gynecology 66(5), 657-660. [ Links ]

Wereszczak, J., Miles, M.S. & Holditch-Davis, D., 1997, 'Maternal recall of the neonatal intensive care unit', Neonatal Network 16 (4), 33-40. [ Links ]

Yali, A.M. & Lobel, M., 1999, 'Coping and distress in pregnancy: an investigation of medically high-risk women', Journal of Psychosomatic and Obstetric Gynaecology 20(1), 39-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01674829909075575 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Rizwana Roomaney

Department of Psychology

University of the Western Cape

Bellville 7535, South Africa

rroomaney@uwc.ac.za

Received: 30 June 2013

Accepted: 10 Apr. 2014

Published: 13 Aug. 2014