Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Health SA Gesondheid (Online)

versión On-line ISSN 2071-9736

versión impresa ISSN 1025-9848

Health SA Gesondheid (Online) vol.18 no.1 Cape Town oct. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Nurses' experiences and understanding of workplace violence in a trauma and emergency department in South Africa

Maureen KennedyI; Hester JulieII

IHuman Resources, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa

IISchool of Nursing, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Violence in South African society has reached epidemic levels and has permeated the walls of the workplace. The aim of the study was to gain a deeper understanding of how nurses experience and understand workplace violence perpetrated by patients, and to make recommendations to reduce this type of violence. A qualitative, exploratory and descriptive study was conducted to explore the experiences and coping mechanisms of nurses regarding workplace violence. The purposive sample comprised eight nurses working in the Trauma and Emergency Department in the Western Cape, South Africa. Thematic analysis was done of the semi-structured interviews. Four main themes and 10 categories were identified. Nurses are experiencing physical threats, verbal abuse and psychological and imminent violence on a regular basis. They tend to 'normalise' abusive patient behaviour because of the perception that workplace abuse 'comes with the territory', which resulted in under-reporting. However, perpetrators received compromised care by being avoided, ignored or given only minimal nursing care. Coping mechanisms ranged from using colleagues as sounding boards, helping out with duties, taking a smoke break and using friends and family to get it 'off their chest'. The tolerance of non-physical violence and the absence of policies to deal with the violence, contribute to under-reporting.

OPSOMMING

Geweld in die Suid-Afrikaanse samelewing het epidemiese vlakke bereik en selfs werksplekke binnegedring. Die doel van die studie was om 'n dieper begrip te verkry van hoe verpleegsters geweld deur pasiënte by die werksplek ervaar en verstaan, en aanbevelings te maak om hierdie tipe van geweld te verminder. 'n Kwalititatiewe, eksploratiewe en beskrywende ontwerp is gebruik om die ervaringe en hanteringsmeganismes te verken van verpleegkundiges wat aan werkpleksgeweld blootgestel was. 'n Doelgerigte steekproef is gedoen bestaande uit agt verpleegkundiges werksaam in die Trauma en Nooddienste Departement in die Weskaap, Suid Afrika. Die semi-gestruktureerde onderhoude is kwalitatief ontleed vir temas. Vier hooftemas en 10 kategorieë is geïdentifiseer. Verpleegkundiges ervaar dreigemente van fisiese geweld, verbale misbruik en psigiese en dreigende geweld gereeld. Hulle is geneig om pasiënte se misbruikende gedrag te 'normaliseer' omdat hulle die persepsie het dat geweld of misbruik 'deel van die werksomgewing' is. Hierdie persepsie gee aanleiding tot onder-rapportering van nie-fisiese geweld en gekompromitteerde sorg deurdat skuldige pasiënte of vermy, geïgnoreer of minimale sorg gegee word. Hanterings meganismes sluit in reflektering teenoor kollegas, uithelp met take, die gebruikmaking van 'n rook breek, en ontlaaing teenoor familielede en vriende. Die toleransie van nie-fisiese geweld en die gebrek van beleidsriglyne dra by tot die onder-rapportering van werksplek geweld.

Introduction

Workplace violence is regarded as being a complex, dangerous and global occupational burden (McPhaul & Lipscomb 2004:168; Schablon et al. 2012:1), especially for the nursing profession (Abualrub & Al-Asmar 2011:157; Kwok et al. 2006:7). The levels of workplace violence in nursing remain unacceptably high, even with the current trend of under-reporting (O'Brien-Pallas et al. 2008:31) and in spite of the mounting evidence pointing to the adverse effects on the caregivers, care receivers and the health institution (O'Brien-Pallas et al. 2008:31-32; Gerberich et al. 2004:495).

The current trend of under-reporting could be ascribed to workplace cultures that either frame workplace violence as part of the job or are in denial regarding patient-related violence (O'Brien-Pallas et al. 2008:32). Only during the last decade has international attention with regard to the issue managed to bring this pandemic to public notice.

Two documents have been instrumental in framing workplace violence as a global occupational hazard and a serious public health issue (Newman et al. 2011:1). The first document is the Joint Programme on Violence in the Health Sector Report (Di Martino 2002) that provided 'guidelines to address workplace violence in the health sector' (Di Martino 2002:iii). This report was the product of collaboration between the International Labour Organization, the International Council of Nurses, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Public Services International.

The second document is the development of a workplace violence typology based on the relationship between the perpetrator and the survivor of workplace violence, by the University of Iowa's Injury Prevention Research Center (UIIPRC 2001). This typology is regarded as being a useful tool because it enables policy makers to design more effective workplace violence-specific intervention strategies for any working setting (McPhaul & Lipscomb 2004:168).

Type 1: This type of violence is due to 'criminal intent' (UIIPRC 2001:4) because the violence is committed during a crime by persons who are not in the employ of the organisation. Thus no official relationship exists between the perpetrator and the survivor.

Type 2: This type of violence is also known as 'customer or client' violence (UIIPRC 2001:4) because the violence is committed during service delivery. This type of violence is very common in healthcare settings, where the perpetrators (clients or their families) direct the violence at the service providers or care givers.

Type 3: This type of violence stems from interpersonal or work-related disputes between current or former employees. It is frequently referred to as horizontal or 'worker-on-worker' violence, because both the perpetrator and the survivor have an official relationship with the organisation (UIIPRC 2001:4).

Type 4: This category refers to the 'spill-over of domestic violence into the workplace' (UIIPRC 2001:11). In this type of violence, the perpetrator has a personal relationship with the employee but not necessarily with the organisation (McPhaul & Lipscomb 2004:171).

All four types of violence are experienced by nurses in healthcare settings and specifically in emergency and psychiatric settings (Catlette 2005:520; Hahn et al. 2008:431).

Although the perpetrators of workplace violence against nurses are varied, researchers have identified patients and their relatives as being the largest perpetrator group (Abualrub & Al-Asmar 2011:158; Wang, Hayes & O'Brien-Pallas 2008:1-3). This trend is confirmed by studies that have investigated this type of violence in emergency settings (Gacki-Smith et al. 2009:340; Gates, Ross & McQueen 2006; Kasangra et al. 2008:1274; Kennedy 2004), general hospitals (Hahn et al. 2008; Magnavita & Heponiemi 2012), community health settings (Kajee-Adams & Khalil, 2010) and psychiatric settings (Bimenyimana et al. 2009; Khalil 2010).

Gates et al.'s (2006:333) investigation into type 2 workplace violence at emergency units in the U.S.A. confirmed that patients were the largest perpetrator group. The majority of the nurses (98%) were harassed verbally, 78% were threatened verbally at least once, 67% had been assaulted physically and 44% had been harassed sexually by patients.

Hahn et al. (2008:431) reported that 85% of healthcare workers in Switzerland have experienced patient-committed violence during their career. Fifty-five per cent of these violations were targeted at nurses, mostly (74%) in emergency settings.

The 'NEXT' study, aimed at identifying the prevalence of violence in nursing in 10 European countries, reported that 22% of nurses experienced frequent violent incidents with patients and relatives (Estryn-Behar et al. 2008:111).

Convincing evidence around the globe indicates that Type 2 workplace violence is increasing in healthcare settings and therefore impacting on nursing.

Definition of key concepts

This study adopted the widely accepted definition of workplace violence by the WHO, because it includes both psychological and physical violence. The WHO, as quoted by O'Brien et al. (2008:31), defines workplace violence as: 'Incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work ... involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health'.

Other key concepts encompassed by the above definition of workplace violence are:

• Verbal abuse, which refers to the intentional use of language that humiliates, degrades or indicates a lack of respect for the dignity and worth of an individual that creates fear, intimidation and anger in the nurse.

• Physical violence, which refers to beating, kicking, slapping, stabbing, shooting, pushing, pinching, scratching and biting that cause physical, sexual or psychological harm to the worker (Di Martino 2002:11).

• Psychological violence or emotional abuse, which refers to behaviour that humiliates, degrades or indicates a lack of respect for the dignity and worth of an individual. It refers to the intentional use of power or threats of physical force against a person or group, which can result in harm to physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development (Di Martino 2002:11).

Researchers postulate that the increase in Type 2 workplace violence can be ascribed to the high levels of societal violence that have infiltrated the healthcare settings (Abualrub & Al-Asmar 2011:157; Newman et al. 2011:11).

Problem statement

The Western Cape Province in South Africa has the highest homicide and assault rates in the country (South African Police Service 2011:27-29) and the supposition is, therefore, that the ripple-effect of societal violence will become evident even in healthcare settings. This supposition that violence is rife in these clinical settings is confirmed by several local studies.

The findings of the impact of crime and violence on health services delivery in the Western Cape by Steinman (2003:8) include that 62.9% of the sample (of which nurses formed 62.5%) indicated that working conditions have worsened; 61.1 % frequently had to deal with crime and violence in the workplace; 46.9% of the doctors regarded violence as being 'part of the job'; 42% perceived that workplace safety was not a priority for the Provincial Department of Health or the City Council; 76.1% did not receive training to defuse threatening and aggressive behavior; and 63.2% were unsure about the availability of workplace violence-related counselling services.

According to Steinman's seminal work (2003:32), the incidence and risks of workplace violence differ significantly between public and private healthcare settings. In the public sector, 67.4% of healthcare workers reported being attacked physically, whilst 42.5% had witnessed physical violence in the workplace, compared with 42.5% and 19.2% respectively in the private sector. This study indicates that healthcare workers in emergency and trauma units, especially in the public sector, are at greater risk of workplace violence.

However, recent studies in the health sector in Cape Town indicate an upward trend in violence in the general and psychiatric hospitals as well as community healthcare settings (Kajee-Adams & Khalil 2010:187; Khalil 2010:191).

The researcher, who was employed in the Employees' Assistance Programme at one of the public hospitals which was part of the sample for the two earlier studies, therefore became concerned about safety issues related to patient-initiated violence.

Aim of the study

The aim of the study was to gain a deeper understanding of how nurses experience and understand workplace violence perpetrated by patients, and to make recommendations to reduce this type of violence.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to:

• explore the interpretation of workplace violence by nurses

• determine the behavioural response of nurses after incidents of workplace violence

• describe the effects of workplace violence on the work performance of nurses

• identify the coping strategies employed by nurses when dealing with workplace violence.

Significance of the study

Limited research has been done in South African hospitals and, more specifically, in the Western Cape, on the issue of violence against nurses. This study will be significant in that it may provide insight into the perceptions and reactions of nurses to workplace violence and possibly contribute to the development of a workplace policy aimed at combating this occupational hazard.

Research method and design

Research design and context of the study

A qualitative, exploratory study was done in the Trauma and Emergency Department at a large academic hospital in the Western Cape of South Africa. The Department consists of four units which are the first point of entry for all trauma and medical emergencies in the surrounding area.

Population and sampling

The population consisted of 29 registered nurses, 16 enrolled nurses and 26 enrolled nursing auxiliaries who work day and night shifts within these units, on a rotational basis. Purposive sampling (Burns & Grove 2005:352) was used because the key informants - nurses regarded to be most knowledgeable about the subject - were identified by their supervisors. The inclusion criteria specified nursing staff with at least one year of work experience within this department. Data sufficiency was ensured because all nursing categories were represented in the sample (De Vos et al. 2005).

Data collection methods

Information sessions took place where the researcher presented an overview of the study, obtained informed consent, identified tentative interviewing slots and decided on the interview venue. The researcher conducted eight semi-structured interviews at the institution using the following interview guide:

1. What is your understanding or definition of violence in the workplace?

2. Have you experienced violence in the work environment and what was your response or action?

3. Did you report the incident?

4. Was your work performance affected in any way after the incident?

5. Which coping strategies did you use?

6. Do you think the staff needs support?

The interviews were audio recorded and observational notes were taken by the researcher in order to enhance self-awareness and identify biases that could affect data analysis negatively.

Data analysis

The researcher transcribed the interviews verbatim. Thematic analysis was conducted using the steps proposed by Tesch as stated in Creswell (2009:186). A priori themes were developed deductively according to the research questions (Ryan & Bernard 2003:88). Open coding was performed manually by the researcher because categories were developed and labelled using descriptive wording. The researcher analysed these categories to determine whether these behaviours or responses occurred in isolation, belonged only to a certain nursing group or occurred in specific situations.

Ethical considerations

Written approval and permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape and the relevant authorities of the academic health institution. Prospective participants were given an overview of the study, briefed on the process of the interviews and informed about their right to withdraw at any stage of the study without any fear of victimisation. Prior to data collection, written, informed consent was obtained. The privacy and confidentiality of the participants were protected as all identifiers were removed from the reports and verbatim quotations.

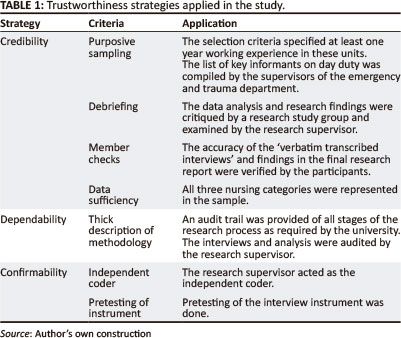

Trustworthiness

Babbie and Mouton (2002) refer to trustworthiness as the concept which ensures neutrality in qualitative research designs. Trustworthiness requires that the researcher employs strategies of credibility, dependability and confirmability (see Table 1 for the strategies applied in this study).

Results and discussion

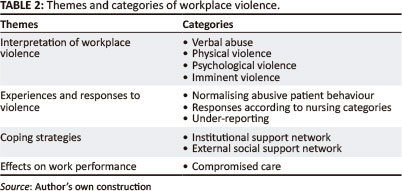

The results of the analysis of the transcribed interviews are summarised in Table 2.

Demographic profile of participants

The sample comprised three female registered nurses, two enrolled nurses (one man, one woman) and three enrolled nursing auxiliaries (one man, two women).

Theme 1: Interpretation of workplace violence

It is evident from the data that the participants interpreted workplace violence broadly and even mentioned imminent violence.

Verbal abuse

This type of violence was experienced by all the participants. Verbal abuse was interpreted as swearing, shouting, scolding and 'hurling words at you':

'Here in Trauma we are exposed to mostly verbal abuse, not really physical abuse. Most of the times it is just swearing ... they are rude to you, they hurl all sorts of words at you ... swearing at you and scolding you'. (29-year-old female enrolled nurse)

This is consistent with other international research findings that report a high prevalence of verbal abuse. Gates (2008:333) reports a prevalence of 94% as reported by emergency workers in general, whilst Gacki-Smith et al. (2009:341) found a prevalence of more than 70% as reported by nurses working in emergency settings in Colombia.

South African studies of nurses in the Western Cape report similar trends. Khalil (2010:191) reports a prevalence of verbal abuse reported by 78% of nurses at general hospitals and 86% of nurses working in community health centres (Kajee-Adams & Khalil, 2010:188).

The danger of this type of workplace violence is the fallacy that it is 'relatively harmless', in spite of the potentially serious psychological effects for nurses (Bilgin & Buzlu 2006:84; Magnavita & Heponiemi 2012), poor patient care (Magnavita & Heponiemi 2012) and nurses accepting the 'normalisation of workplace violence' (Jonker et al. 2008:496).

Physical violence

Physical violence was viewed as any behaviour which would cause physical harm, for example, being kicked, slapped or having objects thrown at them or being threatened. Although none of the research group participants had experienced physical violence, they were subjected to physical threats. As one reported:

'A patient came in and he was rude to one of the nurses, and the next minute I just saw his hand grab for my scissors, and then I just backed off and left'. (46-year-old female nursing assistant)

This finding contradicts other research findings. Gates (2008:333) states that 48% of the emergency workers in the United States reported being assaulted, whilst South African studies reveal that this type of violence is on the increase and is prevalent in both general and psychiatric hospitals. Earlier studies by Van der Spuy and Rontsch (2002:10) indicate that 6.9% of a sample of health workers in general hospitals in the Western Cape sustained minor injuries and 4.6% 'experienced noteworthy physical injury' as a result of assaults by patients over a two-year period. Swart et al. (2010) report that staff working in psychiatric hospitals are assaulted by patients approximately seven to 14 times per month.

Psychological violence

Kajee-Adams and Khalil (2010:188) found that 62% of nurses employed in community health centres received threats of physical assault, which constitutes psychological violence. Psychological violence includes disrespect, rudeness and witnessing of abusive incidents. All participants, except one enrolled nurse, expected violence to happen in their workplace, as reflected in these comments:

'Swearing comes with the territory; sometimes they are gangsters; you need to fight and argue, I don't know what role to play; you know you must go and talk to the people who don't actually listen to you; they just walk past you ... that I feel is abuse, and I said, "You are very rude, your behaviour is unacceptable, and don't talk to me like that"'. (30-year-old female enrolled nurse)

This illustrates that the nurse experiences frustration and low job control, which is associated with non-physical violence according to Magnavita and Heponiemi (2012:115).

However, Gillespie et al. (2010:181) state that setting limits on unacceptable patient behaviour may act as a protective factor against violence-related stress in the workplace, as illustrated by the nurse's comment to the patient above.

The negative effect of workplace violence on the individual and their family is captured aptly in this statement:

'I think most nurses are stressed out ... they take all that home and you hear they have arguments with their kids or husbands and it is so unnecessary'. (46-year-old female nursing assistant)

Magnavita and Heponiemi (2012) confirm that survivors experience high psychological distress and work-related stress as a result of non-physical workplace violence. Unfortunately, only 25% tend to seek professional help, according to Zuzelo, Curran and Zeserman (2009:114).

Imminent violence

It became evident during the interviews that the registered nurses were affected emotionally by the mere thought that they are at risk all the time. They had constant expectations of imminent violence.

'I remember one incident ... a patient came in and he was rude to one of the nurses, and the next minute I just saw his hand grab for my scissors, and then I just backed off and left. I thought here I must better stay away from this man, because I don't know if he wants to get me'. (38-year-old female registered nurse)

Kansagra et al. (2008:1273) reported that 'nurses felt the least safe' of all participants surveyed across 65 emergency departments in the USA. This finding is confirmed by Zuzelo et al. (2012:114), who found that 92% of psychiatric nurses expected to be assaulted by patients. In the Western Cape, perceptions of imminent violence can be ascribed to increased levels of violence in healthcare settings (Kajee-Adams & Khalil 2010:188).

Theme 2: Experiences of and responses to violence

The participants reported that they have either experienced or witnessed all types of workplace violence. Their behaviour and reactions to the violence were influenced by factors such as the diagnosis of the patient, the nursing category and the prevailing organisational culture.

Normalising abusive patient behaviour

It was evident that the nurses' clinical experience in this type of environment has given them insight into patient behaviours. Nurses therefore tolerate abusive behaviour from patients if the violence could be ascribed to some underlying aetiological factor that could cause confusion or aggression in patients:

'Many of them are a little drunk, so we rather let it pass ... like the head injuries ... you know he is confused, and you realise he does not really want to be like that, then one tends to ignore it'. (40-year-old female auxiliary nurse)

The organisational culture in the Trauma and Emergency Department seems to condone tolerance for some abusive patient behaviour:

'Well, I'm used to it ... you work here every day with these kinds of patients, so I don't stress myself ... the swearing comes with the territory'. (40-year-old female auxiliary nurse)

Workplace violence is thus ignored if linked to the patient's diagnosis or due to intoxication because patients are perceived as 'not being in a proper frame of mind' since they 'do not know what they are doing'.

These nurses demonstrate what Zuzelo et al. (2012:123) call 'optimistic caring practices'. They also cite identifying aetiological factors that could influence patient behaviour as a self-protective strategy, even though this type of rationalisation contributes or perpetuates the current trend to under-report all forms of workplace violence.

Physical violence was rated as less acceptable than verbal abuse, with the latter being perceived as 'not as bad as physical abuse'.

The above anecdotes indicate that the institutional culture tends to frame non-physical violence as unavoidable, consequently condoning workplace violence.

These findings warrant concern because research indicates a positive correlation between work-related aggressive incidents and negative emotions, job dissatisfaction, absenteeism, substance abuse, burnout (Bimenyimana et al. 2009:8-10), high staff turnover and intentions to leave the nursing profession (Estryn-Behar et al. 2008:113; Mokoka, Oosthuizen & Ehlers 2011:6).

Responses according to nursing categories

The registered nurses manage physical violence by confronting abusive patients or calling for assistance from security. By virtue of their authoritative position, this is easily accomplished:

'I will confront the patient, I speak to him, not rude but in a loud tone, so he knows that I'm not going to take his nonsense'. (29-year-old female registered nurse who was a shift leader)

However, caution is taken when physical threats are deemed dangerous.

The registered nurses' ability to assess volatile situations rapidly and act appropriately may be the reason that physical violence and verbal threats were diffused. However, their behaviour still changed to that of hypervigilance and caution when interacting with violent patients:

'I'll be around, but when it comes to being with the patient, then I'll just back off ... you know, just to avoid the next confrontation ... you never know what it can lead to'. (Female registered nurse)

O'Brien-Pallas et al. (2008:32) confirm that this type of violence impacts negatively on the psychological health, personal well-being, morale and nursing care of nurses.

The male enrolled nurse, with ten years' trauma nursing experience, could only describe incidents of violence from a witness perspective:

'I think because girls are weak ... most of the patients are scared of male nurses, they therefore take it out on the sisters and nurses'. (40-year-old enrolled male nurse)

Although Mayhew and Chappell (2005:346) agree that female workers experience more verbal abuse than men, they contend that gender difference can be explained by the fact that more women are employed in caring, close-contact jobs such as nursing. Gillespie et al. (2010:177) challenge this view, however, because although some studies confirm that female nurses experienced more verbal and physical abuse than their male counterparts, the difference was insignificant. Estryn-Behar et al. (2008:113) found that male nurses and nursing aides (enrolled nursing auxiliaries) were more at risk of violence compared with female and registered nurses, although men reported lower burnout rates than women.

However, the male enrolled nurse felt obliged to respond in a defensive or an equally, though indirect, abusive manner in an attempt to stop the violence.

The enrolled nursing auxiliary group, responsible for delivering basic nursing care, sometimes found it easier just to ignore the patient and do their 'expected duty'. This group tended to call on the registered nurses to intervene on their behalf instead of confronting the abusive patient themselves:

'If I feel that the patient like really abuses me, then I go to my sister in charge, and she must speak to the patient'. (30-year-old female auxiliary nurse)

Having a supportive team apparently buffers the negative effects of the abuse (Estryn-Behar et al. 2008:107).

Avoidant behaviour and treating the patient with caution seem to be common ways of dealing with volatile situations:

'If a patient is abusive to me, then I don't worry with that patient, I will do my observations, I will ask him a question, and that's it'. (29-year-old enrolled auxiliary nurse)

It is evident from the above narratives that these nurses would benefit from aggression management programmes. Estryn-Behar et al. (2008:113) state that maladaptive responses to violence may 'increase the likelihood of a reoccurrence of violence'. These nurses would feel more confident in their ability to manage potentially violent situations by attending training on de-escalation strategies and other verbal engagement strategies for defusing potentially violent situations, according to Wang et al. (2008:123).

The perception that the nurse needs to be professional in her behaviour and therefore cannot really respond in an equally violent manner came through strongly:

'To fight fire with fire is not going to work'. (29-year-old female registered nurse)

They would rather 'ignore everyday swearing', although they are aware of the negative psychological effects of repressing feelings:

'I think most nurses are stressed out'. (29-year-old female registered nurse)

These statements affirm the findings of scholars around the world (Mokoka, Oosthuizen & Ehlers 2011; van Emmerik et al., 2007:152) that workplace violence adversely affects the total health of nurses and 'strongly influences the recruitment and retention of nurses' (Estryn-Behar et al. 2008: 112).

Under-reporting of violence

All three categories of nurses conceded that verbal abuse was such a common everyday occurrence that reporting this type of abuse was regarded as senseless. They dealt with verbal abuse and violence by using available in-house resources such as security personnel, or getting back-up from peers or doctors.

The enrolled auxiliary nurses verbalised strongly the importance of reporting serious or 'bad abuse', referring to physical violence and aggressive behaviour, for example, threatening to throw objects at them. Zuzelo et al. (2012:113, 124) concur that only very serious incidents are reported because nurses are conditioned to accept workplace violence. The International Council of Nurses cites that only 20% of these incidents are reported officially (Wang et al. 2008:2).

What emerged was the ambivalence in the reporting of violence and being aware of the possible contributing factors, especially if they were medically related. They would often rationalise and accept the abusive or violent behaviour if the patient was confused or intoxicated:

'Why must we report it? You know people are going to get sick of the story, "listen I have been abused"; I think we take it for granted it's going to happen, why report it'. (29-year-old female enrolled nurse)

'If the patient did not physically harm you, it's not necessary to report it'. (29-year-old female enrolled nurse)

The perception is that reporting 'non-physical violence' will have very little impact because it is perceived as 'minor' and as the 'norm'. Steinman (2003:8-12) and Gates et al. (2006:333) respectively confirm that between 50% and 65% of nurses never report verbal abuse. Gerberich et al. (2008:499) report that only 27% of nurses perceived violence to be a problem even though 38% experienced non-physical violence. This trend is troublesome, given the warning by Gerberich et al. (2008:502) that the effects of non-physical violence are more severe than those of physical violence.

O'Brien-Pallas et al. (2008:32) posit that 'this normalisation of workplace violence' is the precursor to institutional violence, while an institutional culture of zero-tolerance is cited as a protective factor against workplace violence (Gacki-Smith et al. 2009:347).

However, one enrolled nurse reflected a 'zero-tolerance stance' by stating categorically that abusive behaviour is unacceptable: '[W]hether they do it physically or whether they do it verbally, for me it is serious' (42-year-old enrolled nurse).

Gillespie et al. (2010:181) state that workers who implement a zero-tolerance policy are more likely to report the abuse, yet the appropriateness of a 'zero-tolerance' policy in emergency settings is questioned. Clear organisational policy on workplace violence and offering regular prevention training programmes are preferred because it empowers the nurses (Wang et al. 2008:10-22).

Theme 3: Coping strategies

The participants realised that people may respond to workplace violence differently, and therefore having support available was deemed important. Coping mechanisms ranged from using colleagues as sounding boards, helping out with duties, taking a smoke break and using friends and family to get it 'off your chest'.

All these strategies have some merits for reducing the negative physical, psychological and attitudinal changes associated with workplace abuse. However, Gillespie et al. (2010) assert that:

... the foremost strategy for violence is an effective workplace violence program focused on preventing violence before it occurs, safely managing violent events, and coping with the psychological consequences that occur after violent events. (p. 179)

Institutional support network

Support was two-fold: physically, peers provide protection against the abuse or take over the nursing care of the violent or abusive patient. Participants depended primarily on their colleagues for emotional support, which provided immediate relief and validation of their feelings. Colleagues have an empathic understanding when feelings like 'I could not face the abusive patient again' are expressed. Having a team to depend on for emotional support was valued more than depending on actions from management, because:

'[T]here is always one of my colleagues to back me up ... we work as a team'. (29-year-old female enrolled nurse)

This finding is supported by Bilgin and Buzlu (2006:80), who reported that 83.3% of psychiatric nurses perceived the nursing team to be emotionally supportive, compared with 50.6% for the nursing management.

The peer support that these nurses received could also be regarded as a protecting factor for patient-initiated violence, according to van Emmerik et al. (2007:168).

External social support network

Family and friends also played a big role by providing the necessary encouragement to deal with the problem of workplace violence:

'Most of the time I will just discuss it or tell somebody about it and eventually it blows over'. (29-year-old female registered nurse)

Schat and Kelloway (2003:181) warn that although social support is effective for reducing the adverse consequences of violent incidents, it has no effect on the imminent fear of future workplace violence or on psychosocial disorders. Schablon et al. (2012:9) concede that only a weak link was found to exist between social support and psychosocial disorders.

It is worth noting that none of the participants mentioned anything about institutional policy when dealing with workplace violence. They did, however, indicate the need for supportive counselling for individuals and peer groups.

This finding is a concern, because 'unsupportive management structures, sub-optimal physical working conditions and workplace violence' were cited as reasons for nurses resigning in the Durban metropolitan area (King & McInerney 2006:70). Management can reduce the negative outcomes of workplace violence and prevent incidents from recurring by providing training in violence management strategies. Schablon et al. (2012:9) report that the risk of experiencing verbal aggression or physical violence is correlated positively with training in violence management.

Theme 4: Effects on work performance

The effects that patients' behaviour had on the work performance of the nursing staff varied. For example, the male nurse felt that it did not affect his work performance since he was used to workplace violence, whereas the female nurses felt that when someone abused them verbally, they were very upset and tended to avoid the patient. The male nurse perceived his role as the 'rescuer' of the weaker female nurses when dealing with difficult patients.

The effects on work performance include attitudinal change and choosing to have minimal interaction with the patient. Generally, all felt their work performance was not affected in the sense of 'the work not being done'; however, their attitude towards the patients were affected. They described this as choosing to have minimal contact with perpetrators by either avoiding or ignoring them:

'I won't say it affects my work, but it definitely affects my attitude towards that patient ... I find myself reluctant to do things for that patient ... I'm just doing it because it is expected of me, but it's definitely not by choice'. (40-year-old enrolled male nurse)

Zuzelo et al. (2012:118) report similar findings among nurses working in psychiatric settings.

The concept of duty versus care emerged quite clearly from this statement. Although basic care requirements are met, interactions with perpetrators lack empathy. This finding confirms the theory that threats of violence will impact negatively on work performance, as evidenced by reduced commitment and dedication (Van Emmerik et al. 2007:155).

Limitations of the study

This study was limited to workplace violence perpetrated only by patients against nurses. A follow-up study into this type of workplace violence should include the relatives accompanying the patients.

Recommendations

On an institutional level, the following recommendations should be considered as strategies to help nurses cope with this occupational hazard. There should be:

• regular support in the form of education and training in the management of workplace violence

• individual and group counselling services to reduce the negative consequences of workplace violence

• clear policy guidelines that specify reporting and monitoring procedures.

Implications for further research flowing from this study are that qualitative investigations are needed in order to understand the factors preventing nurses from responding effectively to verbal abuse in particular. Research could also focus on reducing verbal abuse and improving the nurses' ability to respond to verbal abuse.

Conclusion

The findings indicate that nurses are experiencing physical threats, verbal abuse, psychological and imminent violence on a regular basis. They tend to 'normalise' abusive patient behaviour because it is perceived to 'come with the territory'.

Coping mechanisms ranged from using colleagues as sounding boards, helping out with duties, taking a cigarette break and using friends and family to get it off their chest. The tolerance of non-physical violence, as well as an institutional culture that does not have policies to deal with the violence, contribute to under-reporting. However, the perpetrators received compromised care by being avoided, ignored or given only minimal nursing care.

It can thus be concluded that the aim of the study was reached because the findings provide a better understanding of how these nurses interpret and manage workplace violence.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this paper.

Authors' contributions

M.K. (University of Stellenbosch) conducted the research. H.J. (University of the Western Cape) was the research supervisor and corrected and refined the manuscript.

References

Abualrub, R.F. & Al-Asmar, A.H., 2011, 'Physical violence in the workplace among Jordanian hospital nurses', Journal of Transcultural Nursing 22(2), 157-165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1043659610395769, PMid:21311085 [ Links ]

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J., 2002, The practice of social research, Oxford University Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Bilgin, H. & Buzlu, S., 2006, 'A study of psychiatric nurses' beliefs and attitudes about safety and assaults in Turkey', Issues in Mental Health Nursing 27(1),75-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840500312894, PMid:16352517 [ Links ]

Bimenyimana, E., Poggenpoel, M., Myburgh, C. & Van Niekerk, V., 2009, 'The lived experiences by psychiatric nurses of aggression and violence from patients in a Gauteng psychiatric institution', Curationis 32(3), 4-13. [ Links ]

Burns, N. & Grove, S.K., 2005, The practice of nursing research: conduct, critique, and utilization, Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis. [ Links ]

Catlette, M. 2005, 'A descriptive study of the perceptions of workplace violence and safety strategies of nurses working in level I trauma centers', Journal of Emergency Nursing 31(6), 519-525. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2005.07.008, PMid:16308040 [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W., 2009, Research design, qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, Sage, Thousand Oaks. [ Links ]

De Vos, A.S., Strydom, H., Fouche, C.B. & Delport, C.S.L., 2005, Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions, Van Schaik Publishers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Di Martino, V., 2002, 'Workplace violence in the health sector: country case studies Brazil, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Portugal, South Africa, Thailand and an additional Australian study: synthesis report', viewed 28 November 2012, from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/workplace/WVsynthesisreport.pdf [ Links ]

Estryn-Behar, M., Van der Heijden, B., Camerino, D., Fry, C., Le Nezet, O., Conway, P.M. & Hasselhorn, H.M., 2008, 'Violence risk in nursing - results from the European 'NEXT' study', Occupational Medicine 58(2), 107-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm142, PMid:18211910 [ Links ]

Gacki-Smith, J., Juarez, A.M., Boyet, L., Hofmeyer, C., Robinson, L. & MacLean, S.L., 2009, 'Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments', The Journal of Nursing Administration 39(7-8), 340-349.http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181ae97db, PMid:19641432 [ Links ]

Gates, D.M., Ross, C.S. & McQueen, L., 2006, 'Violence against emergency department workers', Journal of Emergency Medicine 31(3), 331-337. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028, PMid:16982376 [ Links ]

Gerberich, S.G., Church, T.R., McGovern, H.E., Hansen, H.E., Nachreiner, N.N., Geisser, M.S., Ryan, A.D., Mongin, S.G. & Watt, G.D., 2004, 'An epidemiological study of the magnitude and consequences of work related violence: the Minnesota Nurses' study', Occupational Environmental Medicine 61(6), 495-503. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oem.2003.007294, PMCid:1763639 [ Links ]

Gillespie, G.L., Gates, D.M., Miller, M. & Howard, P.K., 2010, 'Workplace violence in healthcare settings: risk factors and protective strategies', Rehabilitation Nursing 35(5), 177-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00045.x, PMid:20836482 [ Links ]

Hahn, S., Zeller, A., Needham, I., Kok, G., Dassen, T. & Halfens, R.J.G., 2008, 'Patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: a systematic review of the literature', Aggression and Violent Behavior 13(6), 431-441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00045.x, PMid:20836482 [ Links ]

Jonker, E.J., Goossens, P.J.J., Seenhuis, I.H.M. & Oud, N.E., 2008, 'Patient aggression in clinical psychiatry: Perceptions of mental health nurses', Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 15(6), 492-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01261.x, PMid:18638210 [ Links ]

Kajee-Adams, F. & Khalil, D., 2010, 'Violence against community health nurses in Cape Town, South Africa', in I. Needman, K. McKenna, M. Kingma & Oud, N. (eds.), Workplace violence in the health sector. Proceedings of the second international conference on workplace violence in the health sector - from awareness to sustainable action, Maastricht, Netherlands, 29 October 2010, pp. 187-188. [ Links ]

Kansagra S.M., Rao, S.R., Sullivan, A.F., Gordon, J.A., Magid, D.J., Kaushal, R., Camargo, C.A. & Blumenthal, D., 2008, 'A survey of workplace violence across 65 U.S. emergency departments', Academic Emergency Medicine 5(12), 1268-1274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00282.x, PMid:18976337, PMCid:3530386 [ Links ]

Kennedy, M.A., 2004, 'Workplace violence: an exploratory study into nurses' interpretations and responses to violence and abuse in trauma and emergency departments', Masters dissertation, Faculty of Community Health, University of the Western Cape, Western Cape. [ Links ]

Khalil, D., 2010, 'Health consumers "right versus nurses' right": violence against nurses in Cape Town, South Africa', in I. Needman, K. McKenna, M. Kingma & Oud, N. (eds.), Workplace violence in the health sector. Proceedings of the second international conference on workplace violence in the health sector - from awareness to sustainable action, Maastricht, Netherlands, 29 October 2010, pp. 191-194. [ Links ]

King, L.A. & McInerney, P.A., 2006, 'Hospital workplace experiences of registered nurses that have contributed to their resignation in the Durban metropolitan area', Curationis 29(4), 70-81. [ Links ]

Kwok, R.P.W., Law, Y.K., Li, K.E., Ng, Y.C., Cheung, M.H., Fung, V.K.P., Kwok, K.T.T., Tong, J.M.K., Yen, P.F. & Leung, W.C., 2006, 'Prevalence of workplace violence against nurses in Hong Kong', Hong Kong Medical Journal 12(1), 6-9. [ Links ]

Magnavita, N. & Heponiemi, T., 2012, 'Violence towards health care workers in a public health care facility in Italy: a repeated cross-sectional study', BMC Health Services Research 12, 108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-108, PMid:22551645, PMCid:3464150 [ Links ]

Mayhew, C. & Chappell, D., 2005, 'Violence in the workplace', The Medical Journal of Australia 183(7), 346-347. [ Links ]

McPhaul, K.M. & Lipscomb, J.A., 2004, 'Workplace violence in health care: recognised but not regulated', Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 9(3), 168-185, viewed 18 September 2012, from http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume92004/No3Sept04/ViolenceinHealthCare.aspx [ Links ]

Mokoka, E., Oosthuizen, M.J. & Ehlers, V.J., 2011, 'Factors influencing the retention of registered nurses in the Gauteng Province of South Africa', Curationis 34(1), E1-9. [ Links ]

Newman, C.J., De Vries, D.H., Kanakuze, J. & Ngendahimana, G., 2011, 'Workplace violence and gender discrimination in Rwanda's health workforce: Increasing safety and gender equality', Human Resources for Health 9, 19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-9-19, PMid:21767411, PMCid:3154143 [ Links ]

O'Brien-Pallas, L., Wang, S., Hayes, L. & LaPorte, D., 2008, 'Creating work environments that are violent free', in I. Needman, K. McKenna, M. Kingma & Oud, N. (eds.), Workplace violence in the health sector. Proceedings of the second international conference on workplace violence in the health sector - from awareness to sustainable action, Maastricht, Netherlands, 29 October 2010, pp. 31-13. [ Links ]

Ryan, G.W. & Bernard, H.R., 2003, 'Techniques to identify themes', Field Methods 15(1), 85-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569 [ Links ]

Schablon, A., Zeh, A., Wendeler, D., Peters, C., Wohlert, C., Harling, M. & Nienhaus, A., 2012, 'Frequency and consequences of violence and aggression towards employees in the German healthcare and welfare system: a cross-sectional study', BMJ Open 2(5), 2:e001420. [ Links ]

Schat, A.C.H. & Kelloway, E.K. 2003. 'Reducing the adverse consequences of workplace aggression and violence: The buffering effects of organizational support', Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 8(2), 110-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.8.2.110, PMid:12703877 [ Links ]

South African Police Service, 2011, 'Crime report 2010/2011. The crime challenge facing the South African Police Service', pp. 1-29, viewed 23 Jan 2013, from www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=127115 [ Links ]

Steinman, S., 2003, Workplace violence in the health sector. Country Case Study: South Africa. Geneva: International Labour Organisation/International Council of Nurses/WHO/Public Services International Joint Programme Working Paper, viewed 09 April 2013 from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WVcountrystudysouthafrica.pdf [ Links ]

Swart, Y., Niehaus, D., Koen, L. & Macris, E., 2010, 'Adverse incident monitoring at a psychiatric hospital in South Africa', in I. Needman, K. McKenna, M. Kingma & Oud, N. (eds.), Workplace violence in the health sector. Proceedings of the second international conference on workplace violence in the health sector .- from awareness to sustainable action, Maastricht, Netherlands, 29 October 2010, p. 189. [ Links ]

University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center, 2001, 'Workplace violence: A report to the nation', viewed 20 January 2013, from http://www.public-ealth.uiowa.edu/iprc/resources/workplace-violence-report.pdf [ Links ]

Van der Spuy, E. & Rontsch, R., 2002, 'Crime and violence in the workplace - effects on health workers, part 2', Injury and safety monitor 1(1), 8-12. [ Links ]

Van Emmerik, I.J.H., Euwema, M.C. & Bakker, A.B., 2007, 'Threats of workplace violence and the buffering effect of social support', Group & Organisation Management 32(2), 152-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1059601106286784 [ Links ]

Wang, S., Hayes, L. & O'Brien-Pallas, L., 2008, 'A review and evaluation of workplace violence prevention programs in the health sector final report', Nursing Health Services Research Unit, University of Toronto, Canada. [ Links ]

Zuzelo, P.R., Curran, S.S. & Zeserman, M.A., 2012, 'Registered nurses' and behavior health associates' responses to violent inpatient interactions on behavioral health units', Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 18(2), 112-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1078390312438553, PMid:22412084 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Hester Julie

Private Bag X17

Bellville, 7535, South Africa

Email: hjulie@uwc.ac.za

Received: 10 Mar. 2012

Accepted: 20 Mar. 2013

Published: 02 July 2013