Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine

On-line version ISSN 2071-2936

Print version ISSN 2071-2928

Afr. j. prim. health care fam. med. (Online) vol.13 n.1 Cape Town 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.2852

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Effect of telephone counselling on the knowledge, attitude and practices of contacts of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Egypt

Randa M. SaidI; Ghada M. SalemII

IDepartment of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt

IIDepartment of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging respiratory illness. The World Health Organization declared it a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020 and called for collaborative efforts, such as contact tracing and promoting the public awareness about COVID-19, and recommended prevention and control measures

AIM: The aim of this study was to assess the effect of telephone counselling on the knowledge, attitude and practices (KAPs) of contacts of COVID-19 confirmed cases towards COVID-19 epidemiology and infection prevention and control measures

SETTING: Ten areas in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt divided into six rural and four urban areas

METHODS: A non-randomised controlled trial was conducted in Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, from 26 March 2020 to 12 April 2020 on 208 contacts of confirmed COVID-19 cases, divided equally into two groups: an experiment group that was exposed to telephone counselling by the researchers and a control group that was exposed to routine surveillance by local health authority. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to assess the KAP of both groups towards COVID-19 before and after intervention

RESULTS: After intervention the percent of contacts who achieved good knowledge, positive attitudes and better practice scores in the experimental group was 91.3%, 57.8% and 71.2%, respectively, compared with 13.5%, 7.8% and 16.3%, respectively, in the control group. Male gender and working group were significantly associated with bad practice score. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between differences in knowledge, attitudes and practices of the experimental group before and after the intervention

CONCLUSION: This study proved the effectiveness of telephone counselling in improving COVID-19-related KAP scores of contacts of confirmed COVID-19 cases

Keywords: telephone counselling; KAP score; contacts of confirmed COVID-19-cases; COVID-19 stigma; routine surveillance; health education; home isolation.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging respiratory illness that was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. The disease is highly infectious, leading to a worldwide pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020 and called for collaborative efforts of all countries to prevent the rapid spread of COVID-19.1

These collaborative efforts include contact tracing and promoting the public awareness about the updates of COVID-19 situation and the recommended prevention and control measures.2 Contact tracing has proven to be effective in controlling sporadic and clusters of cases before they can spread infection.3 Adherence of the public in general and contacts of COVID-19 confirmed cases in particular to prevention and control measures is the mainstay in the battle against COVID-19; therefore, it is necessary to promote this adherence through health education programmes. Numerous studies have shown that health education can change knowledge, unhealthy attitudes and behaviours and can effectively reduce infectious diseases and epidemics.4 Health education will largely affect the knowledge, attitude and practices (KAPs) of target audiences towards COVID-19 according to the KAP theory.5,6

According to the WHO, application of electronic means in providing health services is known as E-health. It is one of the ways to provide health care to people who have difficulty to reach health services because of physical or environmental barriers, insufficient resources or when face-to-face health education measures are not feasible during infection outbreaks.7 There are many varieties of E-health ranging from simple techniques (telephone and facsimile machines) to complex techniques (satellite links and integrated services digital network). Telephone calls are considered to be one of the simplest and least expensive methods to provide health information, education and psychological support for members of the public.8 The effect of telephone counselling is varied; some studies have supported its positive effect, such as the one carried out by Zhu et al.,9 who proved the effectiveness of telephone counselling in smoking cessation, whilst other studies such as that of Allagher et al. did not find any evidence to support the positive effects of telephone counselling.10

At this critical moment, there is an urgent need to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 infection through increasing awareness of contacts of COVID-19 cases towards infection prevention and control measures. Our research question was the following:

-

Can telephone counselling as an easy, inexpensive, and safe method for both health care providers and exposed people increase the abilities of COVID-19 contacts to make informed decisions towards infection prevention and control measures, without succumbing to mistrust and the stigma associated with the disease?

Our study objective was to assess the effect of telephone counselling on KAP of contacts of COVID-19 confirmed cases towards COVID-19 epidemiology and infection prevention and control measures.

Research methods and design

Study design

A non-randomised controlled trial was conducted in all areas with confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Sharkia Governorate from 26 March 2020 to 12 April 2020. They included 10 areas divided into six rural and four urban areas.

Study subjects

The study subjects were contacts of confirmed cases of COVID-19 traced by the local health authorities (LHAs) during the study period. Local health authorities defined a contact as a person who has experienced any one of the following exposures during the two days before and the 14 days after the onset of symptoms of a confirmed case: (1) face-to-face contact with a confirmed case within 1 m and for more than 15 min, (2) direct physical contact with a confirmed case and (3) direct care for a patient with confirmed COVID-19 without using proper personal protective equipment.11

Exclusion criteria

The coronavirus disease 2019 contacts excluded from the study participants less than 18 years old and those living outside the Sharkia Governorate.

Sample size and sampling method

Sample size was calculated to be 182 participants using OpenEpi program depending on the following: confidence interval 95%, power of test 80%, ratio between two groups 1:1, percent of participants with improved KAP scores in the control group compared with intervention group was 60% and 80%, respectively, according to the pilot study, odds ratio 2.7 and risk ratio 1.3. Taking into consideration a dropout of 20%, the total calculated sample size was 218 participants divided equally between two study groups.

All COVID-19 contacts appearing during the study period were included in the study. There were 208 participants who were divided equally into two groups: an experimental group and a control group. They did not appear at the same time but appeared in consecutive clusters depending on appearance of confirmed COVID-19 cases at different times and in different places. So, the first six clusters were chosen to represent the control group, whilst the next four clusters were chosen to represent the experimental group. The number of clusters depended on trying to approximate the calculated sample size of each group.

Tools of data collection

COVID-19 knowledge, attitude and practices questionnaire

It was a semi-structured questionnaire adapted from Zhong et al.12 It was modified by addition of new questions in the attitudes and practices sections so as to be suitable for contacts of COVID-19 cases. It consisted of four parts (items of parts II, III, IV are illustrated in Appendix 1, Table 1-A1).

Part I: Socio-demographic characteristics including age, sex, residence, marital state, education, occupation and social class which were calculated according to Fahmy Socioeconomic Level Questionnaire.13

Part II: There were 12 knowledge questions: four regarding clinical presentations (K1-K4), three regarding transmission routes (K5-K7) and five regarding prevention and control of COVID-19 (K8-K12). These questions were answered on a true/false basis, with an additional 'I don't know' option. A correct answer was given score '1' indicating good knowledge and incorrect answer or 'I don't know' option was given score '0', indicating bad knowledge. The total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 12, with consideration of achieving more than 60% from total score as a good knowledge of COVID-19.

Part III: Four attitude questions (A1-A4) assessed the degree of worry amongst COVID-19 contacts about the following: getting the disease, people talking badly about them, avoiding them by friends and family because of being a contact of COVID-19 case and seeking medical care if they have any symptoms suspicious of COVID-19 because of fear of stigma. These questions were answered on a 'yes/no' basis, where 'Yes' indicated a negative attitude and was scored '0' and 'No' indicated a positive attitude and was scored '1'. The total attitude score ranged from 0 to 4, with consideration of achieving more than 50% from total score as positive attitude.

Part IV: Ten practice questions (P1-P10) assessed the recommended health practices that should be followed by contacts of COVID-19 cases. These questions were answered on a 'yes/no' basis, where 'Yes' indicated good practice and was scored '1' and 'No' indicated bad practice and was scored '0'. The total practice score ranged from 0 to 10, with consideration of achieving more than 60% from total score as a good practice.

Pilot study

Firstly, the content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by three Egyptian experts in the field of epidemiology and research to ascertain relevance and completeness. The experts' responses to every question were represented in four points rating score ranging from 4 to 1, where 4 = strongly relevant, 3 = relevant, 2 = little relevant and 1 = not relevant. Then the summation of these responses was carried out and divided by the total score to calculate the percentage score. Validity of the questionnaire in view of experts' conclusion was found to be 95%. Then the questionnaires were completed through telephone communication with contacts of COVID-19 cases traced in the first two areas where COVID-19 began to appear in Sharkia Governorate and excluded later from the study. The first area was chosen as a control group (number of contacts was 16) and the second as an experimental group (number of contacts 22). In the pilot study, we tried to simulate what would be done during the experiment to ensure applicability of the study. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.75, indicating an acceptable internal consistency.

Fieldwork

Amongst the efforts in Egypt to control COVID-19 pandemic was the formulation of a collaborative protocol between the Ministry of Health and all Faculties of Medicine in the country. This protocol stated that once a confirmed COVID-19 case appears in any place, the faculty staff members will assist the LHAs in surveillance of this person's contacts for 14 days from the last contact with this case (home isolation period). This surveillance depended only on an active daily monitoring for COVID-19 symptoms through phone calls. The control group was exposed to this routine surveillance.

The researchers as faculty staff members received the telephone numbers and the personal data of participants from the LHAs. They phoned them all but its frequency was different amongst the study groups. For the control group, phoning was done only twice at the beginning and one week after the home isolation period. For the experimental group, phoning was done all through the home isolation period and one week after it. All COVID-19 contacts appearing during the study period agreed to participate in the study, providing a response rate of 100%. The study passed through three phases, which are discussed next.

Pre-intervention phase

This phase was conducted on the second or third day of home isolation period where COVID-19 KAP questionnaire was completed through a telephone contact with each participant in both the experimental and control groups after taking consent.

Intervention phase

This was conducted during the home isolation period where the experimental group was exposed to telephone counselling via the researchers whose phone numbers were available to all participants to simulate the hot line. Telephone counselling composed of direct telephone conversations on scheduled alternative days and during any emergency and continuous WhatsApp contact through text messages or voice calls for any non-urgent question. During this counselling, the following was done: monitoring for COVID-19 symptoms; providing short tailored health education messages about the clinical presentations, transmission routes, prevention and control of COVID-19; providing psychological support and solving any health problems that appeared during the home isolation period and which might have led to the need for medical consultation and subsequently non-adherence to home isolation.

Post-intervention phase

This phase was conducted one week after the home isolation period where the same questionnaire of the pre-intervention phase was completed through telephone contact with each participant in both experimental and control groups.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were carried out by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Illinois, United States) version 20.0. Chi-square, McNemar, Fisher's exact tests and correlation co-efficient were measured. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University (reference no: ZU-IRB #6236-26-3-2020).

An official permission was obtained from the Health Directorate in Sharkia Governorate and informed verbal consent was obtained from all the participants after simple and clear explanation of the research objectives to them.

Results

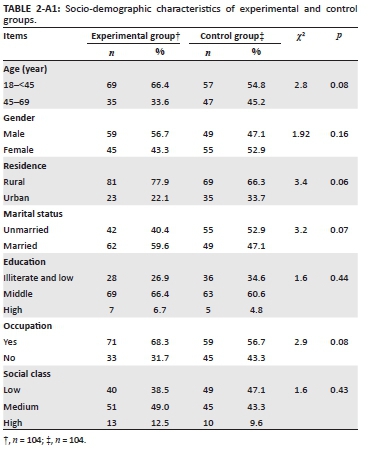

Regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants, there were no statistically significant differences between experimental and control groups in all these variables (Table 2-A1).

Table 1 shows that after telephone counselling, the knowledge of the experimental group significantly improved compared with the control group in all questions covering COVID-19 epidemiology, infection prevention and control. The percent of COVID-19 contacts who achieved a good total knowledge score in the experimental group was 91.3% compared with 13.5% in the control group.

Table 2 shows that after telephone counselling, all attitudes of the experimental group significantly improved compared with the control group. A total of 57.8% COVID-19 contacts achieved positive total attitude score in the experimental group compared with 7.8% in the control group.

Table 3 shows that after telephone counselling, all health practices of the experimental group significantly improved compared with the control group. A total of 71.2% COVID-19 contacts achieved a good total practice score in the experimental group compared with 16.3% in the control group.

Tables 1-3 also show insignificant differences in knowledge, attitudes and health practices of the experimental and control groups at baseline. They also show insignificant changes in knowledge, attitudes and health practices of the control group despite of surveillance with LHA.

Table 4 demonstrates a statistically insignificant association between all socio-demographic factors of the experimental group and the post-intervention KAP scores except the male gender and working group that were associated with bad practice score.

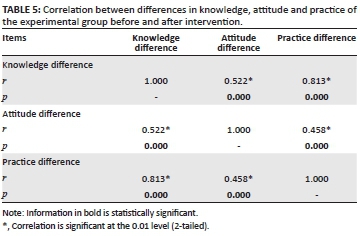

Table 5 reveals a statistically significant positive correlation between differences in knowledge, attitudes and practices of the experimental group before and after telephone counselling.

Discussion

Our study showed that telephone counselling was effective in improving the experimental group's knowledge about COVID-19, decreasing their worry about getting COVID-19 and being exposed to its related stigma and helping them to adhere to the recommended preventative practices. This result is consistent with the study conducted by Chan et al. in China during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic, which found that telephone health education seemed to be effective in producing significant changes of knowledge, relieving anxiety related to the SARS pandemic and improving the practice of identified preventative measures related to SARS.14 From this research it would appear that the lessons learned from the SARS pandemic about the value of telephone counselling can be applied during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the WHO reported that increase in public awareness about the emerging disease played an important role in relieving negative social phenomena such as anxiety, fear and stigmatisation.15 Telephone counselling can be one of the used methods in increasing public awareness during a pandemic.

The effectiveness of telephone counselling can be shown through the following study results: firstly, the statistically insignificant differences between experimental and control groups in all socio-demographic characteristics, which confirms that there was no selection bias; secondly, the statistically insignificant differences between experimental and control groups in baseline KAP scores related to COVID-19, which became statistically significant after telephone counselling; finally, the presence of insignificant changes in KAP scores of the control group in spite of surveillance with LHAs. Local health authorities depended only on an active daily monitoring for COVID-19 symptoms during surveillance of COVID-19 contacts and neglected the practice of health education. This might be attributed to their implicit dependence on health education provided by the Ministry of Health through mass media and official websites without assuring whether this health education is accessible to everyone or satisfies the needs of everyone.

Before telephone counselling, our study revealed low level of knowledge, negative attitude and bad practice towards COVID-19 in both the experimental and control groups. This could be attributed to two factors: firstly, our study was conducted early at the beginning of appearance of COVID-19 at Sharkia Governorate, with low expectation and preparedness for the disease. This is consistent with other studies that reported that the general public lacked good KAP of SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) at the early stage of epidemics.16,17 Secondly, the majority of our participants in both groups were either illiterate or below university education, which will surely affect their KAP. This result is contrary to other studies conducted in China, Egypt and Iran, which used online surveys to assess the KAP of general public towards COVID-19 and which reported high level of knowledge, appropriate practice and positive attitude towards COVID-19.12,18,19 This difference in results may be because of dependence of these studies on online surveys, which are usually accessible for participants with university education. This reflects that although the use of online surveys is an important precautionary measure during the epidemics, the data revealed from them cannot be generalised to the whole population and they should be replaced by more widespread methods, for example, telephone survey.

Our study also revealed that telephone counselling was effective in improving the KAP scores of all participants in the experimental group regardless of their socio-demographic factors except the male gender and working group, which were associated with bad practice score. This could be explained by the fact that men are usually representative of the working group and working conditions may hinder the adherence to home isolation and other preventive practices. Furthermore, our study revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between differences in knowledge, attitudes and practices of the experimental group before and after the intervention and this assures us that effective changes can be produced by telephone counselling.

Limitations of this study included a lack of long-term follow-up that may be needed to track the maintenance of preventive behaviour. Therefore, we recommend that further studies should be conducted for longer periods of time to prove the long-term effect of telephone counselling.

Conclusion and recommendation

Our study demonstrated the effectiveness of telephone counselling, which incorporated active monitoring for COVID-19 symptoms, health education, psychological support and problem-solving in improving the knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 contacts. Conversely, routine surveillance by LHAs that depended only on an active daily monitoring for COVID-19 symptoms through phone contact was not sufficient to change the knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 contacts. This suggests that health authorities should be more aware of the potential of telephone counselling during surveillance of COVID-19 contacts as an accessible, safe and reliable method to improve their KAP about this emerging disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of this study for their great cooperation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

R.M.S and G.M.S. were responsible for the study and contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation was performed by R.M.S. Data management was performed by G.M.S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding information

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

1. World Health Organization. 2019-nCoV outbreak is an emergency of International concern [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/healthtopics/emergencies/pages/news/news/2020/01/2019-ncov-outbreak-is-an-emergency-of-international-concern [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean. WHO delegation concludes COVID-19 technical mission to Egypt [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 4]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/who-delegation-concludes-covid-19technical-mission-to-egypt.html [ Links ]

3. Government of Canada. Public health management of cases and contacts associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novelcoronavirus-infection/health-professionals/interim-guidance-cases-contacts.html [ Links ]

4. Wang M, Han X, Fang H, et al. Impact of health education on knowledge and behaviors toward infectious diseases among students in Gansu province, China. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:6397340. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6397340 [ Links ]

5. Ajilore K, Atakiti I, Onyenankey K. College students' knowledge, attitudes and adherence to public service announcements on Ebola in Nigeria: Suggestions for improving future Ebola prevention education programmes. Health Educ J. 2017;76(6):648-660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896917710969 [ Links ]

6. Tachfouti N, Slama K, Berraho M, Nejjari C. The impact of knowledge and attitudes on adherence to tuberculosis treatment: A case-control study in a Moroccan region. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:52. [ Links ]

7. Chan SS, So WK, Wong DC, Lee AC, Tiwari A. Improving older adults' knowledge and practice of preventive measures through a telephone health education during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(7):1120-1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.019 [ Links ]

8. Blixen CE, Bramstedt KA, Hammel JP, Tilley BC. A pilot study of health education via a nurse-run telephone self-management programme for elderly people with osteoarthritis. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763304322764194 [ Links ]

9. Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quit line for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(14):1077-1093. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa020660 [ Links ]

10. Allagher R, McKinley S, Dracup K. Effects of a telephone counseling intervention on psychosocial adjustment in women following a cardiac event. Heart Lung. 2003;32(2):79-87. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhl.2003.19 [ Links ]

11. World Health Organization. Global surveillance for COVID-19 disease caused by human infection with novel coronavirus (COVID-19): Interim guidance [homepage on the Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 20]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331231 [ Links ]

12. Zhong B, Luo W, Li H, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745-1752. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45221 [ Links ]

13. Fahmy SI, Nofald LM, Shehatad SF, El Kadyb HM, Ibrahimc HK. Updating indicators for scaling the socioeconomic level of families for health research. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2015;90(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.EPX.0000461924.05829.93 [ Links ]

14. Chan SS, So WK, Wong DC, Lee AC, Tiwari A. Improving older adults' knowledge and practice of preventive measures through a telephone health education during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: A pilot study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(7):1120-1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.019 [ Links ]

15. World Health Organization. Social stigma associated with COVID-19 [homepage on the Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: www.epi-win.com/allresources/social-stigma-associated-with-covid19 [ Links ]

16. Bener A, Al-Khal A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards SARS. J R Soc Promot Health. 2004;124(4):167-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/146642400412400408 [ Links ]

17. Bawazir A, Al-Mazroo E, Jradi H, Ahmed A, Badri M. MERS-CoV infection: Mind the public knowledge gap. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(1):89-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.05.003 [ Links ]

18. Abdelhafiz AS, Mohammed Z, Ibrahim ME, et al. Knowledge, perceptions, and attitude of Egyptians towards the novel coronavirus disease (COVID19). J Community Health. 2020;45:881-890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00827-7 [ Links ]

19. Erfani A, Shahriarirad R, Ranjbar K, Mirahmadizadeh A, Moghadami M. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: A population-based survey in Iran [Preprint]. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.256651 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ghada Salem

gadamaged2@gmail.com

Received: 23 Nov. 2020

Accepted: 04 May 2021

Published: 12 July 2021

Appendix 1