Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine

versão On-line ISSN 2071-2936

versão impressa ISSN 2071-2928

Afr. j. prim. health care fam. med. (Online) vol.8 no.1 Cape Town 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1184

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

How to change organisational culture: Action research in a South African public sector primary care facility

Robert MashI; Angela De SaII; Maria ChristodoulouI

IDivision of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

IIDivision of Family Medicine, University of Cape Town and Western Cape Department of Health, District Health Services, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Organisational culture is a key factor in both patient and staff experience of the healthcare services. Patient satisfaction, staff engagement and performance are related to this experience. The department of health in the Western Cape espouses a values-based culture characterised by caring, competence, accountability, integrity, responsiveness and respect. However, transformation of the existing culture is required to achieve this vision.

AIM: To explore how to transform the organisational culture in line with the desired values.

SETTING: Retreat Community Health Centre, Cape Town, South Africa.

METHODS: Participatory action research with the leadership engaged with action and reflection over a period of 18 months. Change in the organisational culture was measured at baseline and after 18 months by means of a cultural values assessment (CVA) survey. The three key leaders at the health centre also completed a 360-degree leadership values assessment (LVA) and had 6 months of coaching.

RESULTS: Cultural entropy was reduced from 33 to 13% indicating significant transformation of organisational culture. The key driver of this transformation was change in the leadership style and functioning. Retreat health centre shifted from a culture that emphasised hierarchy, authority, command and control to one that established a greater sense of cohesion, shared vision, open communication, appreciation, respect, fairness and accountability.

CONCLUSION: Transformation of organisational culture was possible through a participatory process that focused on the leadership style, communication and building relationships by means of CVA and feedback, 360-degree LVA, feedback and coaching and action learning in a co-operative inquiry group.

Introduction

South Africa is in a process of strengthening primary healthcare in order to provide universal coverage and improve equity through the introduction of national health insurance.1 Organisational capacity at a sub-district level is needed to deliver on this aspiration.2 This organisational capacity has been conceptualised as 'hardware' and 'software'.2 Hardware refers to the tangible infrastructure, finances, human resources and technology required. Software refers to the observable skills and competencies as well as the organisational systems and procedures. However, software also refers to the less visible values, norms, relationships, communication and use of power within the health system. These intangible aspects are the hidden drivers of the organisational culture, which is experienced by both patients and staff.

The healthcare workers are the most important resource in the health system. The effective functioning of an organisation not only depends on the competence and technical expertise of its workers but also on their job satisfaction, motivation, engagement and performance.3 Currently, high levels of burnout have been reported, which suggests that healthcare workers, however competent, may not have the emotional and personal resources to form effective patient-centred relationships.4 Healthcare workers are in fact frequently criticised for being abusive and rude.5 Patients may therefore experience an organisational culture that lacks caring, compassion, empathy and support.

At the same time, the staff experience of the organisational culture has been described as strongly hierarchical, with decision making dominated by command and control approaches implemented through organisational silos (of directorates and units), in which management is traditionally seen as an administrative function rather than a proactive process of enabling learning, and in which control is exercised in an authoritarian manner.6

Changing organisational culture has been identified as a key goal in improving the resilience and quality of a resource-constrained health system.6

The Western Cape Department of Health has emphasised that improving health outcomes, quality of care and patient experience is central to their vision.7 Part of their approach to achieving this is a more values-based approach within the organisation that identified caring, competence, accountability, integrity, responsiveness and respect (C2AIR2) as the core desired values.7 Nevertheless, recent cultural values assessment (CVA) have shown that the top 10 current organisational values in the metropolitan district health services included poor sharing of information, cost reduction, confusion, control, manipulation, blame, power, hierarchy and long hours.8 These results indicated that the current organisational culture was limiting staff performance and engagement.

The Negotiated Service Delivery Agreement between the President and the Minister of Health acknowledges the need to strengthen management at the facility level.9 Despite this, there has been very little research on the challenges of organisational transformation at the facility level in South Africa. Retreat Community Health Centre (CHC) was one of the facilities that participated in the CVA8 and after receiving their feedback expressed interest in a process to change their organisational culture. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore how to transform the organisational culture in line with the desired values expressed in the baseline assessment and by the Department of Health.

Methods

Study design

A co-operative inquiry group (CIG) used participatory action research to engage with the question of how to transform organisational culture at Retreat CHC over a period of 18 months. Change in the organisational culture was measured at baseline and after 18 months by means of a CVA survey. The three key leaders at the health centres also completed a 360-degree leadership values assessment (LVA) and had 6 months of coaching based on the feedback.

Setting

Retreat CHC serves the community of Retreat in the City of Cape Town. People living in Retreat are mostly from a low socio-economic background, usually speak either English or Afrikaans and historically belong to the so-called 'coloured' community. The CHC had a facility manager, family physician and nursing managers in charge of operations, trauma unit, HIV unit and maternity unit. There was also a pharmacy manager and an administrative officer in charge of reception. It offered ambulatory primary care services as well as 24-hour emergency care to both adults and children as well as 24-hour maternity services. A multidisciplinary team consisted of a family physician, medical officers, primary care nurses, midwives, pharmacists as well as allied health and dentistry staff. In addition, support services included cleaners, security guards, a porter, a personal assistant and clerks. Total staff complement at the facility totalled 128 people.

Formation of co-operative inquiry group

The purpose of the study and CIG process was presented to a meeting of senior staff, invited by the facility manager, from all the departments at the CHC. Fourteen people consented to participate in the CIG and included the facility manager, family physician, five senior nursing managers, a medical officer, a post basic pharmacist's assistant, nurses working in the preparation room, emergency centre and maternity unit, the supervisor of the general assistants and the radiologist. Towards the end of the CIG process, six additional staff members joined the CIG. These included a new pharmacy manager, a new administrative officer and four other staff who were leading the C2AIR2 club process. As the C2AIR2 club initiative also focused on promoting key organisational values, the management felt it made sense for them to join the CIG. The principal researcher, who was not a member of staff at Retreat CHC, facilitated the CIG.

The co-operative inquiry group process

The CIG followed a cyclical process of planning, action, observation and reflection over a period of 18 months from June 2014 until November 2015. The meetings of the CIG are summarised in Table 1. At the initial meeting, the group reflected on the results of the baseline CVA survey. The researcher then conducted a focus group meeting with staff to make sense of the results of the survey and gave feedback on this at the second CIG meeting. By the third meeting, the group had identified the key issues that they wanted to focus on and planned initial actions to address these. At all subsequent meetings, the group gave feedback on the actions that they had attempted during the previous period, engaged in group reflections and activities to look deeper into the key issues that emerged and spent time planning individual and group actions for the next period. Group feedback and discussions were recorded on digital audio tapes and a summary created immediately after each meeting.

Leadership values assessment and coaching

During June and July 2014, the three key leaders at the CHC (facility manager, family physician and nursing manager) also had 360-degree LVAs conducted. The LVA is said to be a 360-degree assessment because feedback is elicited from managers, colleagues and subordinates who work all around the leader. These LVAs give feedback on how these respondents experienced them as leaders in terms of their values and compared this assessment to their own perceptions. An independent personal coach gave them the feedback and then provided them with 6 sessions of individual coaching over a period of 6-months.

Cultural values assessment survey

All staff at the CHC were invited to complete a CVA survey at baseline (January 2014) and follow-up 18 months later (August 2015). The CVA measured how staff perceived their personal values, the values expressed in the current organisational culture and the values that they would like to see in the future culture. The CVA is a validated tool produced by the Barrett's Values Centre and offers the respondents a list of personal and organisational values to choose from.3 This tool was selected as it was already an accepted approach to measure organisational culture in the Government of the Western Cape and Department of Health. Values could be positive or limiting. Limiting values were ones that usually limit the performance of the organisational system. Each respondent selected their top 10 personal and current and desired organisational values. These were then collated and analysed by the Barrett's Value Centre who provided a detailed report.

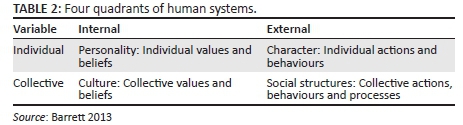

The CVA was used in two different ways in this study. Firstly, the baseline report on organisational culture was used to stimulate reflection and planning in the CIG as described above. An integral model of the organisation was used for this process of reflection.3 In this model, whole system change is based on improving the alignment between all four quadrants of the model shown in Table 2. Personal alignment refers to the extent to which people's personal values are expressed in their professional behaviour as individuals in the CHC. Structural alignment refers to the extent to which the organisational values are expressed in the organisation's structure, processes and procedures. Values alignment refers to the alignment of personal and organisational values and the extent to which people can bring their values to work. Mission alignment refers to the alignment between people's personal behaviour and the organisational structure, processes and procedures and the extent to which people can engage with and commit to the organisational modus operandi.

Secondly, the CVAs performed at baseline and 18 months later were used to compare the extent to which the organisational values had changed over this period. The degree of cultural entropy was also measured, which is the amount of energy in a group consumed in unproductive work and is a measure of the conflict, friction and frustration that exists within a group. It was measured as the percentage of all values selected that were limiting values.

Values could also be analysed as belonging to seven different levels of organisational consciousness as shown in Table 3, and this model was also used to reflect on the transformation required from current to desired organisational culture as well as to monitor the actual transformation over time.3 The top 10 organisational values were plotted according to these seven levels for both the current and desired culture at baseline and follow-up. The pattern that emerged indicated where the organisation was currently investing its energy and what organisational needs were being addressed. Levels without any values could represent a blind spot for the organisation that needed attention, a level that had been fully achieved and did not require attention or an opportunity for future development. A well-functioning organisation should have full-spectrum consciousness with values across all seven levels.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee at Stellenbosch University (Ref N12/10/059) and permission from the Department of Health in the Western Cape.

Results

Organisational culture at baseline

Twenty-five staff members completed the baseline survey, including 5 nurses, 5 allied health professionals, 11 support staff and 4 unknown. The top 10 personal, current and desired organisational values are shown in Figure 1 and plotted against the seven levels of organisational consciousness. Five of the values in the current organisational culture were limiting values (control, cost reduction, long hours, confusion, not sharing information), which were likely to be reducing staff engagement and organisational performance. Overall levels of cultural entropy were high (33% of all values selected were limiting values), which according to the Barrett's Centre report implied serious problems requiring cultural and structural transformation, leadership development and coaching. Caring was a value shared across all three domains, while commitment was the only other personal value found in the current culture. Personal values of respect, fairness and accountability were asked for in the desired culture. Patient satisfaction and open communication were present in both the current and desired culture. The desired culture asked for a shift of focus to levels 2 and 5 indicating a need to pay more attention to relationships, building a sense of community and shared purpose. The values at level 1 and 3 were hindering organisational performance, and staff asked for a focus on excellence instead of these values.

These results were presented to both the staff and CIG, and the final interpretation of these organisational values is given in Table 4.

Following the feedback described above, the CIG summarised the key issues as improving communication, building relationships, reducing the perception of cost reduction as a driving force and increasing accountability.

Organisational culture at follow-up

The follow-up CVA was completed by 75 staff members, including 5 doctors, 41 nurses, 7 allied health professionals and 22 support staff. The results are shown in Figure 2.

At follow-up there were no limiting values in the top 10 values and cultural entropy had dropped from 33 to 13%. Caring had moved to the top value experienced at the health centre, and all three personal values that were previously asked for as part of the desired culture (respect, fairness and accountability) were now recognised as part of the current culture. Teamwork, making a difference and continuous improvement were also recognised in the current culture and mirrored the values of teamwork, positive attitude and excellence that were also previously asked for in the desired culture. Information sharing was now an unequivocal part of the organisational culture suggesting that communication was improving. Patient orientation had replaced goals orientation in the current culture.

The concentration of values in the current culture at level 4 suggested a focus on organisational transformation and an emerging ability to deliver on this. In the desired culture, staff continued to ask for a greater focus on relationships (level 2), shared community and purpose (level 5). There was still a need to make accountability, staff recognition and fulfilment a greater part of the current culture. More open communication, transparency and accessibility were aspired to, even though information was more shared. Staff remained committed to excellence and being the best.

Strategies used to transform organisational culture

The CIG reached a consensus on the activities that were responsible for transforming organisational culture and ranked them as shown in Table 5.

A large number of the strategies involved changing the managers' leadership style through their willingness to engage with the issue of organisational culture, personal coaching and involvement in the CIG. Managers became more confident, open, vulnerable, approachable, collaborative, appreciative and empathic. Small changes in their approach to leadership led to a large change in the way the organisational culture was perceived. Managers felt that the process illuminated key aspects of the organisation that had not previously been recognised as important. The coaching process also led to greater bonding and teamwork between the managers.

Communication of information and decisions were improved as well as opportunities for feedback from staff to managers. Relationships between staff members and teamwork were improved by ensuring that different departments understood each other's functioning, social events, social media and delegation of responsibility within teams. The action research process itself and the C2AIR2 club groups were recognised as important parts of the process of change.

Discussion

Key findings

The study affirmed that despite the many resource constraints and workload challenges in the public sector, organisational transformation is possible at the level of the primary care facility where the majority of patients and health problems are seen.

Cultural entropy decreased dramatically, indicating that the organisation was functioning better, although entropy should still be reduced further to less than 10% for healthy functioning.3 The key drivers of this transformation were change in the leadership style and functioning through feedback from the CVA and LVA, personal coaching of the three key leaders and engagement of broader leadership in the CIG process.

Retreat CHC moved from a culture that emphasised hierarchy, authority, command and control to one that established a greater sense of cohesion, shared vision, communication, appreciation, respect, fairness and accountability. Trusting the majority of your professional staff to strive for excellence, to innovate and to care for patients instead of fearing that you needed to police, blame or manipulate them into delivering on goals was a fundamental shift. The willingness of leaders to engage with these issues and allow small changes in their approach to leadership led to substantial improvement.

Discussion in relationship to literature and policy

The study took a values-based approach to understanding organisational culture and leadership. Organisations often espouse a set of values, without the ability to actually embody them 'on the floor'.3 This study has demonstrated how values can be engaged with practically to drive change. The integral model outlined in the methods section was a key conceptual framework to make sense of the links between personal and collective values as well as individual behaviour and collective processes and procedures. The focus group interviews, which contextualised the meaning of these values, were also a key part of grounding these values in reality.

The study also confirmed that changing the leadership style was the key factor in enabling this transformation. Managers at Retreat CHC came to embody the concept of managers who led rather than just administered.6 Managers who lead have been characterised as focusing on collaborative actions taken by groups, seeing the possibilities to make things better, taking responsibility and initiative to tackle challenges, focusing on activities that are aligned with results that matter, displaying generosity and concern to serve the common good and inspiring others to do the same.6 The organisational culture is largely created by the type of leadership; therefore, it makes sense that leadership transformation would be a key driver of improving organisational culture.3

Developing self-awareness, managing oneself and continuing personal development were key aspects of the coaching process, while improving interpersonal skills was a key aspect of the CIG approach, which focused on relationship building, teamwork, networking and communication. These aspects of emotional and social intelligence may be somewhat missing from the South African competency framework for assessment of managers.10

Different approaches to developing leadership have been identified, such as formal training, on-the-job training, action learning and non-formal training.6This study demonstrated the potential of action learning combined with on-the-job coaching and 360-degree feedback to do this successfully. A number of initiatives in South Africa have focused on more formal leadership courses and teaching, whose impact may be more limited.6 Action learning is a less utilised, but potentially more comprehensive approach to developing leadership.6

The approach to transforming organisational culture and leadership was congruent with a model of complex adaptive leadership that sees the organisation as a complex living system rather than a machine defined by reporting lines within an organogram.11 Complex adaptive leaders are more comfortable with uncertainty, understand the importance of connectivity and feedback within the system and the inevitability of holding paradoxical principles, for example, the need to set a number of simple rules for the organisation, while allowing people individual freedom to act within their scope of practice.

Limitations

Members of the CIG were selected by the management without fully understanding the nature of action research. Lack of understanding their roles resulted in some frustration and participants leaving the process. Those that stayed behind benefitted from the relationships that were built and hierarchical barriers that were broken down. In hindsight, it may have been better to have taken longer to explain the process and allow departments to have more say in choosing the members. This may have led to a CIG in which people were more committed to both action and reflection. People's sense of freedom to interact and be honest grew over time and became a strength of the group. Combining the CIG with the C2AIR2 club leaders also created some confusion and meant accommodating new members towards the end of the whole process. Transformation may have been even greater if the personal coaching had continued for longer and been extended to a broader managerial group.

The surveys were completed by different numbers of people in different proportions according to their professional roles. The follow-up survey is likely to be more accurate as the response rate is better (75/128, 59%). Although the response rate for the baseline survey is low (25/128, 20%) the results are consistent with those previously obtained for the MDHS as a whole in 2011.8

Recommendations and implications

Although a substantial improvement in organisational culture was seen, the momentum needs to be maintained and this may require ongoing external facilitation. Consideration should be given as to how to take such a process to scale within an entire sub-district or district.

It should be noted that out of the five CHCs that participated in the original survey,8 Retreat CHC was the only one that was ready to explore change in this way. The principal researcher ensured that the facility manager and key leaders were aware of and committed to the process beforehand. This suggests that managers may be at different stages of change. Some may be pre-contemplative or unconscious of the need to change, while others may be ambivalent about the importance of change or sceptical about how to change. Exploring the current leadership style and readiness to change of managers at different facilities may be an important aspect of going to scale with this approach.

Further research should try to explore the relationship between improved organisational culture, staff engagement and satisfaction and the quality of care offered to patients. The effect on levels of staff burnout and ability to be patient-centred could also be explored.

Conclusion

Organisational culture at Retreat CHC was transformed over a period of 18 months with a substantial decrease in cultural entropy and embodiment of positive values such as caring, sharing information, teamwork, accountability, respect, client orientation, fairness, commitment, continuous improvement and making a difference. This was achieved through transformation of the leadership style and a focus on communication and building relationships by means of CVA and feedback, 360-degree LVA, feedback and coaching and action learning in a CIG.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the members of the CIG: H. Lemmetjies, A. De Sa, C. Kleinhans, C. Adams, A. Karki, B. Janson, L. Smith, C. Coetzee, L. Fourie, N. Peko, W. Samodien, J. Luzayadio, E. Lucas, N. Albertyn, J. Pekeur, A. Williams, S. Konze, C. Cyster, T. George-Ngwenya and M. Prinsloo. We are grateful to Prof. H. Conradie for performing the focus group interview with the three leaders. We are also grateful to the Department of Health for sharing the results of the follow-up CVA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

R.M. was the principal researcher who conducted the baseline CVA as a trained Barrett's Value Centre consultant. R.M. also facilitated the CIG and captured the group's learning. R.M. wrote the draft manuscript, which was edited and approved by the other authors. A.D.S. conceptualised the project with R.M., participated fully in the CIG and approved the final manuscript. M.C. gave feedback on the LVAs, coached the three leaders and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Matsoso M, Fryatt R, Andrews G. The South African Health Reforms 2009-2014: Moving towards universal coverage. Pretoria: Juta and Company; 2015. [ Links ]

2. Elloker S, Olckers P, Gilson L, Lehmann U. Crises, routines and innovations: The complexities and possibilities of sub-district management. In: Padarath A, English R, editors. South African Health Review 2012/13. Cape Town: Health Systems Trust, 2013; p. 161-173. [ Links ]

3. Barrett R. The values-driven organization: Unleashing human potential for performance and profit. London: Routledge; 2013. [ Links ]

4. Rossouw L, Seedat S, Emsley RA, Suliman S, Hagemeister D. The prevalence of burnout and depression in medical doctors working in the Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality community healthcare clinics and district hospitals of the Provincial Government of the Western Cape: A cross-sectional study. S Afr Fam Pract. 2013;55(6):567-573. [ Links ]

5. Scheffler E, Visagie S, Schneider M. The impact of health service variables on healthcare access in a low resourced urban setting in the Western Cape, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2015;7(1):Art. #820, 11 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v7i1.820 [ Links ]

6. Lucy G, Daire J. Leadership and governance within the South African Health System. In: Padarath A, English R. editors. South African health review 2011. Cape Town: Health Systems Trust, 2011; p. 69-80. [ Links ]

7. Western Cape Government: Health. Healthcare 2030: The road to wellness. Cape Town: Department of Health; 2014. [ Links ]

8. Mash RJ, Govender SC, Isaacs A-A, De SA, Schlemmer A. An assessment of organisational values, culture and performance in Cape Town's primary healthcare services. S Afr Fam Pract. 2013;55(5):459-466. [ Links ]

9. Government of South Africa. Negotiated service delivery agreement: Health [homepage on the Internet]. [ Links ] [cited 2016 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/MediaLib/Downloads/Home/Ministries/Departmen tofPerformance MonitoringandEvaluation3/TheOutcomesApproach/Health%20Sector%20NSDA.pdf

10. Department of Public Service and Administration. Senior management services public service handbook. Pretoria: Department of Public Service and Administration; 2003. [ Links ]

11. Obolensky MN. Complex adaptive leadership: Embracing paradox and uncertainty. Farnham: Gower; 2014. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Robert Mash

rm@sun.ac.za

Received: 18 Mar. 2016

Accepted: 11 July 2016

Published: 31 Aug. 2016