Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Journal of Human Resource Management

On-line version ISSN 2071-078X

Print version ISSN 1683-7584

SAJHRM vol.22 Cape Town 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v22i0.2304

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Succession planning mediates self-leadership and turnover intention in a state-owned enterprise

Reshoketswe S. Maroga; Cecile M. Schultz; Pieter K. Smit

Department of People Management and Development, Faculty Management Sciences, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: This study is a response to the challenges faced by a rail, port and pipeline company in South Africa when managing succession planning, self-leadership and turnover intention

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The study aimed to determine if succession planning was the mediating variable between self-leadership and turnover intention in a state-owned enterprise

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: The study's findings may assist public entities in prioritising succession planning and self-leadership development initiatives

RESEARCH APPROACH/DESIGN AND METHOD: The study adopted a quantitative approach and a cross-sectional survey research design within positivism. Data were gathered using a structured existing questionnaire that was distributed and the response rate was 78.67%. The reliability of the questionnaire was 09.222 which was an indication that the internal consistency was in order. Data were analysed by using correlation and multiple regression analysis

MAIN FINDINGS: The study found that self-leadership was a marginally significant predictor of turnover intention. A large proportion of the sample was drawn from respondents working in Johannesburg whose views might not correspond with those of employees from other areas

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The findings of the study offer government policymakers the opportunity to develop policies that enhance self-leadership, promote succession planning, reduce the intention to leave among employees and incentivise the process

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: The body of knowledge was expanded in the sense that succession planning was found to be the mediating variable in the relationship between self-leadership and turnover intention

Keywords: succession planning; self-leadership; turnover intention; state-owned enterprise; talent management.

Introduction

The state-owned transport enterprise as a whole plays an important role in advancing South Africa's strategic and economic goals, and it is actively updating its brand as it expands into new areas, diversifies its service offering and redefines its market position. The eight state-owned enterprises are run independently, thus employees wanting to move from one enterprise to another need to resign from one entity and be re-appointed in the other enterprise. The question that this study seeks to answer is if succession planning mediates self-leadership and turnover intention in a state-owned enterprise.

The study focused on only one specialist unit that executes large capital infrastructure development projects. The unit has departments in all the operating divisions. The unit has a chief executive, eight general managers, top management, senior management, area specialists, professionally qualified employees, middle management, skilled technicians, academically qualified workers, junior management, supervisors, foremen, superintendents and administrative positions. There are eight technical and administrative departments namely, Human Resources; Finance and Information and Communication Technology (ICT); Projects and Construction and Management; Capital Governance and Controls; Capacity Development Services; Capital Planning and Advisory; Engineering and Design Services; and Capital Enterprise Services.

According to Bano et al. (2022), succession planning is a method of identifying essential management jobs, beginning with project managers and supervisors and progressing to the top position in the organisation. Succession planning also refers to the process of ensuring that management positions are designed to provide maximum flexibility in lateral management moves and to ensure that as individuals advance in their careers their management skills broaden and become more generalised and aligned with organisational rather than purely departmental objectives (Okwakpam, 2019). Poorly managed succession planning is characterised by decisions that cause employee dissatisfaction, resulting in high turnover (Nagel & Green, 2021). Leaders who are hired outside the organisation call for higher salaries, but have higher turnover rates (Allgood et al., 2013). The financial costs of a lack of succession planning motivated this study, as drawing the relationship between succession planning and turnover intention provides useful insights for the public sector HR on effective succession planning.

The abilities and skills required to lead critical function business units or an organisation as a whole are not always the same as those required for intermediate or specialised management levels (Olufemi, 2021). According to Gordon and Overbey (2018), it is critical to recognise that the process of developing systematic succession planning is analogous to implementing a long-term culture change.

Turnover is defined as the individual movement across the membership boundary of an organisation (Belete, 2018). Barton (2019) describes turnover intention as the final cognitive decision-making process of voluntary turnover. Furthermore, other scholars such as Wöcke and Barnard (2021) explain that employees' cognitive process for withdrawal comprises thoughts about quitting the job, searching for another job and intending to leave. Naidoo (2017) states that in today's business environment, employee turnover is considered to be one of the most daunting issues. Furthermore, top management turnover has a huge negative impact on the employees (Løkke & Sørensen, 2021).

Browning (2018) defines self-leadership as 'the process by which individuals influence themselves to accomplish desired results through self-motivation and self-direction'. Self-leadership, as a broader aspect of self-influence, is founded on the assumption that individual behaviour is governed by a mental process, which is then in turn impacted by the effects of behaviour (Uzman & Maya, 2019). Essentially, this is a self-influence attitude that is concerned with bringing oneself to self-motivated performance. According to Wang et al. (2016), self-leadership is the capacity to influence one's thoughts, feelings and behaviours to attain one's goals. Self-leadership boosts intentional activity, which has direct implications for personal growth, leadership and high-performing teams (Ugoani, 2021).

According to Luedi (2022), the nature of leadership is evolving in today's dynamic and fast-paced organisations. Top-down, bureaucratic leadership practices of the past industrial period no longer make sense in a knowledge-based environment characterised by complexity and volatility (Olufemi, 2021). In these times of economic uncertainty and fierce competition, many businesses are abandoning the traditional top-down leadership paradigm in favour of a new model of leadership that entails empowering employees at all organisational levels to take greater responsibility for their work-related behaviours and actions (Uzman & Maya, 2019). Furthermore, today's highly educated and motivated individuals are increasingly encouraged to lead themselves and share essential leadership positions that were formerly held by a typical vertical leader (Boonyarit, 2023).

Al Aina and Atam (2020) believe that talent management is important for the following reasons: (1) effective talent management ensures that organisations can successfully acquire and retain essential talent; and (2) employee engagement relates to an employee's intellectual connection to his or her job, manager, and - most importantly - colleagues. According to Mistri et al. (2019), as the talent shortage grows, more employers are paying attention to the needs of stressed-out and ageing workers, attempting to retain employees and implement effective talent management mechanisms to address employee burnout. These measures could include being treated with respect, doing interesting work, experiencing a feeling of accomplishment, having effective performance reviews and being held accountable for performance goals as agreed with the line managers (Mahfoozi et al., 2018).

Carter et al. (2019) indicate that most traditional succession plans focus mainly on which individuals should advance to the next position in the hierarchy of jobs. Modern succession planning practices should address talent assessment and compel managers to identify those most prepared for the job. Barton (2019) adds that this identification is done in advance, so in the case of retirement there is always a successor in the pipeline. Essentially, the purpose of the succession plan is to identify: (1) which jobs will be vacant at a particular point in time; and (2) which individuals will have the necessary skills, talent and expertise to fill those vacancies (Olufemi, 2021).

Previous research indicates that succession planning mediates self-leadership and turnover intention (Okwakpam, 2019; Stewart et al., 2019), but is not clear if this is the case in a South African state-owned transport enterprise. This study aims to close this research gap.

Purpose of the study

This research investigated if succession planning was the mediating variable between self-leadership and turnover intention in a state-owned enterprise. The objective of the study was to determine if there was a significant relationship between succession planning, self-leadership and turnover intention at a state-owned enterprise.

Literature review

Succession planning in organisations

Researchers define succession planning as an organisation's method of continual recognition, appraisal and nurturing of talent in key roles so that those individuals are in place to ensure leadership stability over time (Barton, 2019; Olufemi, 2021). Succession planning is also understood as a deliberate and organised initiative for an institution to keep its leadership, preserve and advance its intellectual resources and encourage staff development (Budhiraja & Pathak, 2018). Succession planning practices in public institutions have been investigated to clarify their relationships with turnover intention and personal leadership (Ahmad et al., 2020). Karikari et al. (2020) researched successful succession planning models being used in the public sector, with an emphasis on the public universities in Ghana. The study concluded that the success could be ascribed to the understanding that universities had a duty to nurture academics to become experts in their fields so that they could occupy leadership roles.

Three succession planning approaches have emerged as influential in fostering a systematic and constructive process to groom, identify and recruit leaders to replace those leaving the organisation (Rosenthall et al., 2018). Strategic leader development, emergency succession planning and departure-defined succession planning are the three succession approaches (Barton, 2019).

Strategic leader development is described as an ongoing internal practice shaped by the goal of defining an agency's strategic vision, determining the leadership and management skills needed to realise that vision, and recruiting and retaining talented individuals capable of improving those skills (Rosenthall et al., 2018). Strategic leader development succession planning entails developing career growth programmes to create a team of skilled people within the organisation that will fulfil the organisation's potential leadership needs (Karikari et al., 2020). According to (Ahmad et al., 2020), organisations are exposed to a plethora of information on the internet or in archives, scholarly journals or books, explaining how knowledge economy companies craft and implement plans to stay competitive.

Emergency succession planning is a distinct approach to succession planning (Ahmad et al., 2020). The primary aim is to ready an organisation for the unexpected exit of key executives (Gordon & Overbey, 2018). Because succession planning can be a delicate topic, the process can be referred to as 'emergency backup planning' or 'emergency leadership planning' instead of 'emergency succession planning' (Gordon & Overbey, 2018, p. 60). This will help secure key individuals' buy-in and challenge their perception of the mechanism as a threat to their positions (Ahmad & Keerio, 2020).

Departure-defined succession planning seeks to develop leadership capabilities in an organisation so that it can reduce its reliance on the incumbent's talents, charm and relationships and maintain equilibrium without him or her (Chang & Busser, 2020). This strategy, if correctly planned, would ensure that enough time is allotted for either handover to the newly identified successor (Ahmad et al., 2020) or locating and training the newly identified successor in the skills required to carry out his or her responsibilities. Organisations may benefit from departure-defined succession planning in identifying successors (Gordon & Overbey, 2018) so that they do not face a disaster when a core member of staff exits. The studies that have explored succession planning approaches highlight the importance of succession planning in organisations (Ahmad & Keerio, 2020). However, they focus on private organisations which are run differently from the public organisations which are the subject of this study.

Turnover intention

Employee turnover has posed a challenge to businesses. The success of the corporation is primarily dependent on those who work there. The happier the workers, the better for the company, as none of them is likely to leave anytime soon (Oh & Kim, 2019). Companies all over the world are struggling to retain workers, especially those who occupy key positions in the company. According to Belete (2018), one of the widely researched challenges of successful organisations is maintaining valuable staff. Today's businesses still attempt to hold on to staff members considered important assets because they are resources for the company's activities (Oh & Kim, 2019). This is of concern to all companies because turnover leads to substantial costs associated with the recruiting process as well as a lack of productivity (Xu et al., 2022).

The turnover intention has been described as an employee's voluntary, conscious and reasonably strong recurring intentions to leave an organisation (Oh & Kim, 2019). These repeated feelings and plans to leave the organisation initiate a cognitive process that is compounded by influences arising both inside and beyond the organisation, resulting in the ultimate decision to leave the organisation (Oh & Kim, 2019). The following considerations are used in this withdrawal cognition process: (1) thinking about leaving the company, followed by (2) a successful quest for another job elsewhere and (3) final intention to resign or depart (Fyn et al., 2019). Turnover intention is generally recognised as the strongest indicator of workforce turnover (Oh & Kim, 2019). This purpose is always difficult for organisations to discover until the employee shares it with members of the organisation.

The causes of turnover intention in organisations have been subject to intense scrutiny. Windon, Cochran, Scheer and Rodriguez (2019) investigated factors affecting turnover intention among extension programme assistants at Ohio State University. They found a substantial correlation between employees' age, years of service, work satisfaction, supervisor satisfaction, organisational loyalty and plans to leave.

The relationship between job satisfaction and the desire to quit is influenced by organisational engagement (Oh & Kim, 2019). Increased workplace satisfaction has an impact on workforce effectiveness and work efficiency, and it helps companies maintain their workers (Fyn et al., 2019). Oh and Kim's study (2019) made an important contribution to identifying the connection between organisational engagement and intention to leave. However, it involved a university setting in a particular geographical location. The organisational culture of American state institutions varies greatly from that in South Africa. As a consequence, the current study offers a context-based analysis of the phenomenon. The contribution of this study lies in the fact that the relationship between the three variables was tested in a South African context.

Self-leadership

Self-leadership is the deliberate influence of thoughts, feelings and behaviour on goals (Inam et al., 2021). In a professional context, self-leadership requires a transformation in behavioural and cognitive habits that results in interventions intended to increase sense of satisfaction, desire to work smarter and accomplish more, and ability to think constructively about problems that can contribute to the accomplishment of goals set for oneself (Byrant, 2021). The philosophy of self-leadership comprises two dominant fields: self-managing teams and inspiring leadership. According to Goodridge (2019), the essence of self-leadership is self-exploration, self-recognition, self-control and self-growth. These four elements do not work in isolation, but rather complement one another (Goodridge, 2019). To be a good self-leader, one must cultivate all four. The first foundation is self-awareness (Inam et al., 2021). This means that being a great leader requires first considering oneself. According to Goodridge (2019), all people have ideals and principles that characterise them. As people's approach to life and relationships is driven by these principles they should be explored, together with what people are passionate about. This introspection will facilitate discovery of and adherence to principles and ideals - the true self.

Self-acceptance is the second most significant pillar of self-leadership. Self-acceptance is described by Goodridge (2019) as being completely frank with oneself and embracing it without self-criticism or self-sabotage. Self-acceptance is crucial for a leader because when things are not going well, it helps leaders first to realise and then to accept their part in the state of affairs (Thompson, 2018).

Self-management is the third and most significant pillar of self-leadership. Thompson (2018) suggests that leaders who are capable of self-management are more creative, focused and capable of functioning efficiently by themselves. Goodridge (2019) defines self-management as keeping yourself accountable and ensuring that you use your time and money efficiently. Boonyarit (2023) argues that a leader who can self-manage knows that the most precious tools are time and energy and that striking a reasonable balance between the two will produce the desired self-leadership. Self-management is correlated with a variety of essential characteristics and behaviours.

Finally, self-development is an integral part of self-leadership. According to Goodridge (2019), self-growth occurs when one is frank about oneself, but without self-criticism. Self-development is about knowing what one is doing, what works and what does not, and how one can make meaningful improvements (Stewart et al., 2019). As a result, the leader gains a sense of transparency and responsibility for doing the right thing. For self-growth to occur, the leader must be open to feedback and dedicated to self-growth.

Development of the hypotheses

Succession planning and self-leadership

Extant literature has explored the subjects of succession planning and self-leadership. For example, Peters-Hawkins et al. (2018) conducted a study to better understand how software businesses managed the growth of leaders and succession planning processes while also engaging managers. The study identified three key strategies for promoting self-leadership - networks, reflection and action learning. The study recommended that organisations should know how to balance leadership development and succession planning, as this could help to reduce turnover intention (Peters-Hawkins et al., 2018). A related study conducted by Lowan and Chisoro (2016) investigated strategic leader development succession planning at Kwalita Business Consultants. Strategic leader development succession planning entails developing career growth programmes to create a team of skilled people within the organisation that will fulfil the organisation's potential leadership needs (Bano et al., 2022).

Boonyarit (2023) investigated the relationship between self-leadership and proactive work behaviour (PWB). The study found that self-leadership might have the potential to be associated with positive work behaviours and that self-leadership had a profound impact on all four foundations of genuine leadership, namely self-consciousness, equilibrium processing, emotional openness and internalised moral viewpoint (Boonyarit, 2023). The above studies on succession planning and self-leadership ignored the contextual differences between private organisations and public entities, which should have been looked at differently.

Action learning relates to leadership development through the actual practice of tasks in real job situations (Oduwusi, 2018). Succession planning can also be effectively done. The fact that action learning is problem- or project-based is one of its benefits. Individual development is linked to the practice of assisting businesses to respond to important business challenges through action learning (Ahmad et al., 2020). It is related to succession planning by enhancing an individual's skills and competencies.

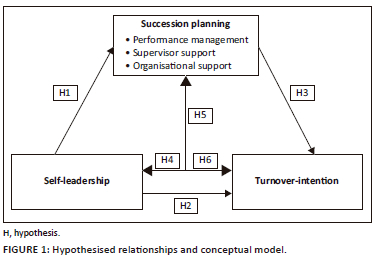

The relationship between succession planning and self-leadership highlighted the following hypothesis:

H1: Succession planning positively relates to self-leadership.

Succession planning and turnover intention

Succession planning is becoming increasingly important in many organisations. It helps organisations to groom future leaders within the organisation (Zulqurnain & Aqsa, 2018). In an era of global competition for talent, succession planning enables organisations to address turnover intention among employees. Therefore, effective succession planning practices are key to retaining talented employees (Owolabi & Adeosun, 2021).

A study conducted by Ahmad and Keerio (2020) established that employees who demonstrated high levels of devotion to their employers were more likely to be successful and to not consider quitting the organisation. Budhiraja and Pathak (2018) argue that fruitful succession strategies are initiated with effective hiring processes - it has been proven that employees who are competent enough stay longer in the firm.

Recent studies indicate that ineffective hiring practices without a clear strategy for employee development increase employee turnover in two forms (Owolabi & Adeosun, 2021; Xu et al., 2022). The first is that the recruits fail to satisfy the demands and expectations of the job. The second is that higher-level personnel will become frustrated as they feel obliged to compensate for the shortcomings of the less capable staff. To reduce potential turnover intention, organisations should therefore immediately create opportunities for self-leadership and employee growth to avoid frustrating existing employees.

Self-leadership is a quality that employees can gain from mentoring (Stewart et al., 2019). Effective mentoring instils a sense of trust and loyalty to the organisation. Organisations that use loyalty strategies in succession planning essentially have higher employee efficiency and lower employee turnover intention (Pila et al., 2016). The techniques to minimise turnover intention include raising the salaries of employees, offering training and development opportunities, involving employees in decisions that affect them and listening to them (Boonyarit, 2023). Researchers have not only confirmed conclusions reached since the early 19th century on why workers leave organisations, but also included other factors like engagement with employees, giving feedback, helping employees understand their weaknesses and devising strategies for improvement (Stewart et al., 2019).

The relationship between self-leadership and turnover intention highlighted the following hypothesis:

H2: Succession planning positively relates to turnover intention.

Self-leadership and turnover intention

Pila et al. (2016) describe self-leadership as the process by which people manage their behaviours, gain influence and lead themselves via the use of certain behavioural and cognitive tactics (Thompson, 2018). There is a link between self-leadership and the desire to quit.

Existing research has looked into the link between self-leading leadership and employee intention to resign. Tetteh and Asumeng (2020), for example, studied the influence of affective commitment on self-leadership and employee turnover intention. According to the findings of the study, affective commitment completely mediates the association between self-leadership and employee turnover intention. This suggests that successful commitment reduces an employee's desire to resign, while increasing trust and readiness to follow the organisation's leaders' vision, philosophy and ideology (Pita & Dhurup, 2019).

From the literature on self-leadership and turnover intention, it can be deduced that employees should continuously work towards self-leadership as a way to generate job satisfaction, growth and fulfilment of goals.

The relationship between self-leadership and turnover intention is highlighted by the following hypothesis:

H3: Self-leadership positively relates to turnover intention.

Succession planning mediates self-leadership and turnover intention

Research indicates that succession planning mediates self-leadership and turnover intention (Okwakpam, 2019; Stewart et al., 2019). Boonyarit (2023) confirms the relationship between self-leadership and turnover intention and recommends that organisations come up with strategies to promote self-leadership and succession planning as a particular point of departure to address problems related to turnover intention. Stewart et al. (2019) highlight that self-leadership can be enhanced by celebrating small wins as a method of achieving even greater success. Organisations must know how to balance leadership development and succession planning as this can help to reduce turnover intention (Pita & Dhurup, 2019).

Relationship between succession planning (performance management system), self-leadership and turnover intention

A performance management system is often described as a structured approach to measuring an organisation's employees' performance (Winarto & Chalidyanto, 2020). During this phase, the organisation aligns its tasks, goals and targets with existing resources (such as workforce, materials and so on), processes and priorities (Chandra & Saraswathi, 2018). The approach to desirable performance evaluation is the collection and application of objective performance data to achieve competitive organisational objectives (Chandra & Saraswathi, 2018).

Leroy et al. (2018) highlight that performance management systems mediate self-leadership and turnover intention. The lack of performance management systems may result in low employee motivation and push employees to think about leaving the organisation (Nagel & Green, 2021).

Performance management systems help the organisation to identify challenges such as internal and external forces which impede the capacity of employees to perform (Okwakpam, 2019). These forces can be mitigated by implementing succession planning and nurturing employees who are loyal to the organisation and who can provide a competitive advantage to the organisation (Oduwusi, 2018). Employee development programmes are a means of achieving this. If employees are happy that their organisation is concerned about their growth, they are likely to have a higher level of satisfaction in their jobs. They also tend to be committed to the company as they believe that the company offers them a bright future and will take good care of their contributions. Luedi (2022) argues that employees who show high levels of commitment to their jobs are more likely to be successful and to not consider leaving the organisation.

The mediation by succession planning (performance management system) of self-leadership and turnover intention is highlighted by the following hypothesis:

H4: Succession planning (performance management system) mediates self-leadership and turnover intention.

Succession planning (supervisor support), self-leadership and turnover intention

Supervisor support is described as how much leaders respect their employees' efforts and care for their well-being (Budhiraja & Pathak, 2018). A leader who receives proper guidance from his or her bosses listens to, values and cares for the opinions of his or her employees (Abid et al., 2019). Supervisor support (SVS) from the organisation's management has a positive influence on employees' affective commitment (Ahmad et al., 2020). Affective commitment to the supervisor, which denotes a solid bond between workers and their managers, is very likely to have a significant impact on employees' work-related attitudes and behaviours and reduce intention to leave the organisation (Luedi, 2022).

The concept of fairness is often related to supervisor support. This definition applies to work effort-reward equity (Eisenbeger et al., 2016). The concept relates to how employees measure the worth of their contributions against the incentives and benefits they earn. Job efforts include a variety of investments, like the time, resources, expertise, experience and intelligence required for the completion of job tasks. Pita and Dhurup (2019) highlight attentive supervisor assistance as a way to increase employee job satisfaction. By implication, supervisor support entails offering employees opportunities for development that foster self-leadership. In turn, employees who feel the organisation supports them are less bound to think of leaving the organisation. Winarto and Chalidyanto (2020) investigated the importance of supervisor support in forecasting employee job satisfaction in a private hospital in Indonesia. They found that workers who had a high degree of work satisfaction were in good physical and mental health. Employees perceived that their jobs provided them with material, meaning and growth opportunities; hence, they felt attached to the organisation (Winarto & Chalidyanto, 2020).

The mediation by succession planning (supervisor support), self-leadership and turnover intention is highlighted by the following hypothesis:

H5: Succession planning (supervisor support) mediates self-leadership and turnover intention.

Succession planning (organisational support), self-leadership and turnover intention

Perceived organisational support (POS) is defined as the general belief among employees that their employer values their contribution and cares about their well-being. Research indicates that there is a positive relationship between organisational support and self-leadership and turnover intention (Li et al., 2022). These findings are supported by Chang and Busser (2020), who established that there was a strong link between POS and employee job satisfaction.

Satisfied employees have lower turnover intention than disgruntled ones. In addition, organisational support facilitates self-leadership as employees are inspired when they see the organisation expressing interest in them, paying attention to them, honouring them and supplying them with resources for promotion within the organisation (Abid et al., 2019). In turn, they feel obliged to improve their behaviour and develop positive attitudes to work and the organisation (Suárez-Albanchez et al., 2022). Employees will be motivated to help the company achieve its goals if they feel they have positive POS. Perceived organisational support will result in an improvement in in-role and extra-role average efficiency and a reduction in depression and habits such as absenteeism and turnover (Li et al., 2022). Perceived organisational support affects employees' long-term dedication (Li et al., 2022) and elicits well-known affective reactions such as process pleasure and good temper (Chang & Busser, 2020).

The mediation by succession planning (organisational support), self-leadership and turnover intention is highlighted by the following hypothesis:

H6: Succession planning (organisational support) mediates self-leadership and turnover intention.

Figure 1 is a graphic representation of the hypotheses.

Research design

Research approach

Positivism was used as the research paradigm. A quantitative approach was used to evaluate the factors contributing to turnover intention and self-leadership while determining if succession planning was the mediating variable between self-leadership and turnover intention in a state-owned enterprise. Quantitative research allows for a broader study, involving a greater number of subjects and enhancing the generalisation of the results; there is also greater objectivity and accuracy (Aspers & Corte, 2019). The research was done at a state-owned company in the freight logistics sector of one of the specialist units in South Africa. The company had five operating divisions and specialist units.

The study targeted 545 permanent employees classified as executives, top management, senior management, professionally qualified employees, experienced specialists, middle management, skilled technicians, academically qualified workers, junior management, supervisors, foremen and superintendents within a state-owned company in the freight logistics sector of one of the specialist units. Purposive sampling was used in this investigation. The strategy allowed the researcher to choose a sample based on personal assessment (Benoot et al., 2016). The sample size was derived from one of the operating divisions dealing with infrastructure development. The company had five operating divisions and specialist units. Furthermore, the study only focused on C-F levels in one of the special units. The categories of managers were senior management, management, industry experts, professionals, specialists, middle management, skilled technicians, employees with an academic qualification, employees in junior management positions, supervisors, foremen and superintendents.

The questionnaires were distributed to 300 of the total population of 545. A basic random sample strategy was used in this investigation.

Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect data from participants. In this study, the data gathering instrument was laid out as follows:

-

Part A: Biographical information of the respondent (7 questions).

-

Part B: Questions pertaining to succession planning (27 questions).

-

Part C: Questions pertaining to turnover intention (3 questions).

-

Part D: Questions pertaining to self-leadership (27 questions).

The following questionnaires were used to measure the relationship between the three variables in this study:

-

Succession planning questionnaire: The standardised questionnaires that were used to collect data were developed by Pila et al. (2015).

-

Turnover intention questionnaire: Riley originally developed the turnover intention questionnaire which was adopted for the study (Camman et al., 1979).

-

Self-leadership questionnaire: For the collection of data relating to self-leadership, the study adopted the questionnaire developed by Houghton et al. (2012).

Part A asked for biographical information in the form of a choice question, but Parts B through D used a Likert scale to express assertions. A 6-point Likert scale was employed, with 1 indicating strongly disagree, 2 indicating disagree, 3 indicating somewhat disagree, 4 indicating slightly agree, 5 indicating agree and 6 indicating completely agree.

In addition, self-administered questionnaires are cost-efficient as the researcher does not have to hire surveyors and they safeguard the anonymity and privacy of respondents who in turn feel freer to give honest responses.

Descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis and inferential statistics in the form of Spearman's correlation coefficients and multiple regression analysis were used to analyse the data. For the analysis, SPSS 24 was utilised. This software was chosen because it provides an efficient and organised way to manage large and complex data sets and perform advanced statistical analysis, making it an essential tool for measuring the relationships between variables.

Ethical considerations

The ethical tenets relevant to conducting research were observed in this study. They were:

-

All standard ethical guidelines, principles and procedures were adhered to during data gathering. This research was carried out following the Tshwane University of Technology ethics guidelines on the letter FCRE2018/FR/10/022-MS (2).

-

The researcher applied for ethics clearance prior to the data collection.

-

Permission was requested from the state-owned enterprise to contact the employees.

-

In collecting data, the researcher first obtained permission from the respondents by way of informed consent.

-

The informed consent form contained information that outlined what the study sought to achieve and further explained the rights of the participants.

-

Participants were given information regarding the goal of the study as well as the possible advantages of the investigation.

-

The responses gathered from research participants were kept anonymous and confidential.

-

Participation in the study entailed risks, discomforts and/or inconveniences that were no greater than the risks, discomforts and/or inconveniences encountered in everyday life.

-

No data were collected or retained on the personal details of participants.

-

Participation in this study was entirely voluntary. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage without having to explain the reason why and without any penalty or future disadvantage whatsoever.

Results

Demographic profile of the respondents

The questionnaires were distributed to 300 of the total population of 545. Two hundred and twenty-seven questionnaires were completed and returned, which represents a response rate of 78.67%. Of the 227 respondents, male respondents made up a bigger proportion (59.5%) than female respondents (40.5%). This is because the company focuses on capital projects for engineering, a field historically dominated by males in the workforce. The age group 26-35 years had the largest percentage of participants (41.4%). Those aged 36-45 years made up 35.7% of the sample, while 40 respondents (17.6%) were between the ages of 46 and 55 years, followed by those aged 56-65 years (4.0%); those aged 25 and under made up the lowest number (1.3%).

Most participants held positions as skilled technicians, academically qualified employees, junior management, supervisors, foremen and superintendents (F level) (61.2%). This was followed by those with professionally qualified, experienced experts and middle management (E level) roles (22.5%). The senior managers (D level) constituted 11.9% and several participants held top management (B&C level) positions (4.4%). This shows that the vast majority of employees were competent. Managers were targeted to complete the questionnaire due to the sample frame (levels A-F).

Strategies employed to ensure validity and reliability

To study the grouping of the items and their connection to original theoretical scales and to assess concept validity, factor analysis was used. According to Saunders et al. (2009), construct validity assesses whether a measuring tool measures the constructs that it is designed to measure. It is critical for determining a method's overall validity.

A principal axis factor analysis with direct Oblimin rotation was used with 0.4 cut-off loadings. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) can be used to determine if data are adequate for factor analysis (Kaiser, 1970). Kaiser (1970, p. 402) states that 'the KMO should be 0.60 or higher to proceed with factor analysis'. Kaiser (1970, p. 402) proposes a 0.4 cut-off value and a preferred value of 0.8 or above. According to Field (2009, p. 660), Bartlett's sphericity test should be significant. The KMO was first conducted to ensure sample adequacy. The sample adequacy measure for succession planning was 0.920, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (p = 0.000), indicating sampling adequacy. Furthermore, the KMO sampling adequacy metric for self-leadership was 0.819 and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant at (p = 0.000), indicating sampling adequacy. It was high enough in all three situations to proceed with the factor analysis. Several factor solutions for succession planning were thus investigated, and the best factor solution was found to be a three-factor solution, explaining a total of 55%:

-

Sub-factor 1: Organisational support.

-

Sub-factor 2: Supervisor support.

-

Sub-factor 3: Performance management system.

The KMO value was 0.632, which is an acceptable level, and only 1 factor was suggested by the Kaiser criterion, explaining 72.280% of the variance. The turnover intention was therefore retained as a unidimensional scale.

The KMO measure of sampling adequacy for self-leadership was 0.819, which is acceptable, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant at (=0.000), which indicates sampling adequacy for self-leadership. A two-factor solution was the result of the factor analysis:

-

Sub-factor 1: Behavioural awareness and volition.

-

Sub-factor 2: Constructive cognition.

Cronbach's alpha was used as a measure of internal consistency to assess variables. A Cronbach's alpha of 0.70 or above suggests adequate dependability (Bryman & Bell, 2007). All three factors of succession planning showed high reliability of 0.70, which point to acceptable reliability. Inter-item correlations all fell within the guideline of 0.1 to 0.5.

A reliability test was done using Cronbach's alpha to assess the dependability of the survey. According to Roller and Lavrakas (2015), the dependability of a study is proved when a research instrument used for data collection can offer similar findings when employed frequently under similar settings across time.

The reliability of the current study's questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach's alpha. Cronbach's alpha is a measure of reliability that measures the internal consistency or median correlation of items in a survey instrument. Middleton (2016) points out that Cronbach's alpha has a range of 0 to 1, with 0 being the least internal consistency and 1 representing the most internal consistency. A Cronbach's alpha of 0.7 or higher indicates strong reliability. The researchers confirmed the content and face validity of the research instrument by pilot-testing it in 17 distinct positions encompassing all areas in the specialist unit where the study was conducted. Before use, this was done to verify that it was aligned with what it was designed to measure and to determine if the questions were understood and interpreted efficaciously and in the manner that they were expected to be interpreted. Roller and Lavrakas (2015) emphasise the importance of instrument validation in determining if an instrument measures what it is meant to assess.

In terms of the correlation between succession planning and self-leadership, it was found that behavioural awareness and volition showed small positive correlations with organisational support (r = 0.182), supervisor support (r = 0.256) and performance management system (r = 0.290)as seen in Table 1. These correlations were all significant at the 0.01 level of significance. Constructive cognition showed small to negligible correlations with organisational support (r = 0.160), performance management system (r = 0.151) and supervisor support (r = 0.090). While the first two correlations were significant at the 0.05 level of significance, the latter was insignificant. Overall, the relationship between self-leadership and succession planning was thus practically small. The interest of the study related more to the relationship between these two constructs and turnover intention. The turnover intention had a small yet significant correlation with supervisor support (r = −0.292), while its correlations with organisational support (r = −0.308) and performance management system (r = −0.341) were moderate. All were significant at the 0.01 level of significance.

Lastly, the correlations of turnover intention with self-leadership were non-significant in both behavioural awareness and volition (r = 0.001) and constructive cognition (r = 0.061). There was thus no relationship between self-leadership and turnover intention. It seems that not all the variables had significant relationships.

Discussion

Regarding the correlation between succession planning and self-leadership, it was found that behavioural awareness and volition showed small positive correlations with organisational support (r = 0.182), supervisor support (r = 0.256) and performance management system (r = 0.290). These correlations were all significant at the 0.01 level of significance (H1).

The results are consistent with previous studies (Oduwusi, 2018) which established that self-leadership had a profound impact on all four foundations of genuine leadership, namely self-consciousness, equilibrium processing, emotional openness and internalised moral viewpoint. In addition, Palvalin et al. found a connection between employee self-management practices and operational excellence.

The results revealed that turnover intention showed a small yet significant correlation with supervisor support (r = −0.292), while its correlations with organisational support (r = −0.308) and performance management system (r = −0.341) were moderate. All were significant at the 0.01 level of significance (H2). The results slightly deviate from those of other studies (Ahmad et al., 2020; Budhiraja & Pathak, 2018) which found a strong relationship between succession planning and turnover intention. These studies argue that fruitful succession strategies are initiated with effective hiring practices - it has been proved that employees who are competent enough stay longer in the firm (Okwakpam, 2019).

The correlations of self-leadership with turnover were non-significant in both behavioural awareness and volition (r = 0.001) and constructive cognition (r = 0.061). There was thus no relationship between self-leadership and turnover intention. It seems as though not all the variables had significant relationships (H3). The findings are contrary to those from other studies (Boonyarit, 2023; Stewart et al., 2019) which established that there was a strong relationship between self-leadership and succession planning. Research indicates that self-leadership generates affective commitment, which in turn completely mediates the association between self-leadership and employee turnover intention. This suggests that successful commitment reduces an employee's desire to resign while increasing trust and readiness to follow the organisation's leaders' vision, philosophy and ideology (Stewart et al., 2019).

In terms of determining if succession planning (performance management system, supervisory support and organisational support) mediates self-leadership and turnover intention, multiple regression analysis was used.

Mediation 1: Performance management used as mediator

For the purposes of the first mediation, the following variables were used:

Y = Turnover intention

X = Self-leadership

M = Performance management system

The analysis establishes the total effect of X on Y. This represents path c in the model. Table 2 highlights the mediation model. The regression of self-leadership on turnover intention, ignoring the mediator, was not significant, b = 0.114, p = 0.487.

The regression of the self-leadership on the mediator and performance management system was significant with b = 0.437, p = 0.002. The table also depicts that the mediator affected the outcome variable (estimate and test path b). However, it needs to be controlled for the independent variable. In this case, the relationship between the performance management system and turnover intention was significant (b = −0.5204, p = 0.000), controlling for self-leadership (H4).

Mediation 2: Supervisor support used as mediator

In the second mediation, supervisor support was used as mediator. The relevant output is provided below.

For the purposes of the first mediation, the following variables were used:

Y = Turnover intention

X = Self-leadership

M = Supervisor support

In table 3, the analysis revealed that controlling supervisor support was not a significant predictor of turnover intention (b = 0.2745, p = 0.0820). In this case, the relationship between supervisor support and turnover intention was significant (b = −0.4394, p = 0.000), controlling for self-leadership (H5). The results were consistent with the results of a study conducted by Thompson (2018) which confirmed that increased self-leadership where the employee had developed self-awareness and positive emotions was associated with higher job satisfaction, affective commitment and lower turnover intention.

Mediation 3: Organisational support used as mediator

In the third mediation, organisational support was used as mediator. The relevant output is provided below.

For the purposes of the first mediation, the following variables were used:

Y = Turnover intention

X = Self-leadership

M = Organisational support

In table 4, the analysis revealed that controlling mediator (organisational support), self-leadership was a marginally significant predictor of turnover intention (b = 0.3221, p = 0.0431). In this case, the relationship between supervisor support and turnover intention was significant (b = −0.4394, p = 0.000), controlling for self-leadership (H6).

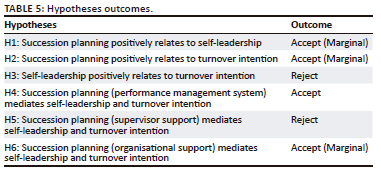

The outcomes of the hypotheses are presented in Table 5.

It is clear from Table 5 that Hypotheses 1, 2 and 6 were marginally accepted while Hypotheses 3 and 5 were rejected. Hypothesis 4 was accepted.

Practical implications

The findings of the study can be used by the government and managers to develop policies that enhance self-leadership and succession planning and reduce the intention to leave among employees. Currently, South Africa is experiencing high youth unemployment and the government can start addressing the problem of the ageing population, particularly those with scarce skills, by bringing in young graduates and helping them develop self-leadership as part of succession planning. Incentivising government departments and managers that take measures to promote talent and skills development and reduce turnover intention will ensure that there is buy-in from managers who may be sceptical of the policy.

Limitations and recommendations

In conducting the study, some limitations were experienced. Firstly, a large proportion of the sample comprised respondents who worked in Johannesburg. This indicates that the results may not accurately reflect what other employees from other towns think. Secondly, information within state-owned enterprises is generally restricted and this prevented some respondents from freely sharing their views. Lastly, this study was cross-sectional and cannot be generalised to other contexts.

Based on the results of the study, the following recommendations are put forward:

-

The state-owned enterprise needs to revise salaries and workload policies since the majority of the employees do not stay long in the company.

-

The state-owned enterprise should consider recruiting more females, as only 92 respondents out of 227 were female. This indicates a serious hindrance in recruiting and retaining them.

-

The company must improve the way it conducts performance appraisals. The process must be clear, fair and transparent to all employees. The fact that 38.7% disagreed with the way they were conducted points to poor implementation.

-

The company should consider revising the way it conducts succession planning and talent management. Given the fact that 34.4% disagreed and strongly disagreed with the way they were implemented, a large proportion of employees were not satisfied.

Future research

Future research could be conducted in the following areas:

-

This study was primarily focused on a specific South African state-owned company and the findings may not be replicated in the private sector because of contextual differences and different organisational cultures.

-

This research could also be expanded to all state-owned company employees to determine if succession planning is the mediating variable between self-leadership and turnover intention. This increases the availability of experienced and capable employees who are prepared to assume roles as they become available.

-

A qualitative study can be conducted to obtain rich data about the self-leadership, succession planning and turnover intention of employees at state-owned enterprises in South Africa.

Conclusion

The main purpose of this study was to establish if succession planning was a mediating variable between self-leadership and turnover intention at a state-owned enterprise. The data revealed that succession planning, self-leadership and turnover intention all had a strong link. If leaders are developed through activities such as action learning, reflection and cultivating networks, employees may gain a deeper understanding of who they are and their purpose within the organisation. The study's findings can assist with new insights for managers on motivating employees and ºoffering them ample opportunities for personal growth for effective succession planning, development of leaders and low turnover.

Acknowledgements

Ms Magriet Engelbrecht who assisted with the language editing and Dr Liezel Korf who assisted with the statistical analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

R.S.M. conducted her research and C.M.S. was the supervisor and P.K.S. was the co-supervisor.

Funding information

This research was funded by Transnet People Management.

Data availability

The data were kept electronically.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and are the product of professional research. It does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institution, funder, agency, or that of the publisher. The authors are responsible for this article's results, findings, and content.

References

Abid, G., Contreras, F., Ahmed, S., & Qazi, T. (2019). Contextual factors and organizational commitment: Examining the mediating role of thriving at work. Sustainability, 11(17), 4686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174686 [ Links ]

Ahmad, A.R., & Keerio, N. (2020). The critical success factors of succession planning in Malaysian public universities. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(5), 4028-4040. [ Links ]

Ahmad, A.R., Ming, T.Z., & Sapry, H.R. (2020). Effective strategy for succession planning in higher education institutions. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 7(2), 203-208. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.72.203.208 [ Links ]

Al Aina, R., & Atan, T. (2020). The impact of implementing talent management practices on sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability, 12(8372), 2-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208372 [ Links ]

Allgood, S., Faulkner, E.J., & Farrell, K. (2013). Big ideas. University of Nebraska. Retrieved from https://business.unl.edu/news/big-ideas-sam-allgood-and-kathleen-farrell/?contentGroup=inside_cba

Aspers, P., & Corte, U. (2019). What is qualitative in qualitative research? Qualitative Sociology, 42, 139-160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7 [ Links ]

Bano, Y., Omar, S.S., & Ismail, F. (2022). Succession planning best practices for organizations: A systematic literature review approach. International Journal of Global Optimization and Its Application, 1(1), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.56225/ijgoia.v1i1.12 [ Links ]

Barton, A. (2019). Preparing for leadership turnover in Christian higher education: Best practices in succession planning. Christian Higher Education, 18(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2018.1554353 [ Links ]

Belete, A.K. (2018). Turnover intention influencing factors of employees: An empirical work review. Journal of Entrepreneurship & Organization Management, 7(3), 2-7. [ Links ]

Benoot, C., Hannes, K., & Bilsen, J. (2016). The use of purposeful sampling in a qualitative evidence synthesis: A worked example on sexual adjustment to a cancer trajectory. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(21), 2-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0114-6 [ Links ]

Boonyarit, I. (2023). Linking self-leadership to proactive work behaviour: A network analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2163563. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2163563 [ Links ]

Browning, M. (2018). Self-leadership: Why it matters. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 9(2),14-18. [ Links ]

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2007). Business research methods (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Budhiraja, S., & Pathak, U.K. (2018). Dynamics of succession planning for Indian family-owned businesses: Learning from successful organizations. Human Resource Management International Digest, 26(4), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-11-2017-0167 [ Links ]

Byrant, A. (2021). Self-leadership. Retrieved from https://www.selfleadership.com/what-is-self-leadership

Carter, J., Young, M., & Alderson, K.J. (2019). Contributions and constraints to continuity in Mexican-American family firms. Journal of Family Business Management, 9(2), 175-200. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-08-2018-0022 [ Links ]

Camman, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire, unpublished manuscript.

Chandra, G.R., & Saraswathi, B.A. (2018). A study on the concept of performance management system in IT industry literature review. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, 9(1), 511-520. [ Links ]

Chang, W., & Busser, J.A. (2020). Hospitality career retention: The role of contextual factors and thriving at work. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(1), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2018-0831 [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R., Glen, P., & Presson, W.D. (2016). Optimising perceived organisational support to enhance employee engagement. Society for Human Resource Management, 5(3), 56-65. [ Links ]

Field, A. 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd ed. Sage.

Fyn, A., Heady, C., Foster-Kaufman, A., & Hosier, A. (2019). Exploring academic librarian turnover and retention strategies. Proceedings of Association of College and Research Libraries Conference (pp. 139-149). Cleveland, Ohio.

Goodridge, A. (2019). The 4 pillars of self-leadership. Time to focus on you. Retrieved from https://thriveglobal.com/stories/the-4-pillars-of-self-leadership-time-to-focus-on-you/

Gordon, P., & Overbey, J.A. (2018). Succession planning, promoting organisational sustainability. Springer.

Houghton, J.D., Dawley, D., & DiLiello, T.C. 2012. The abbreviated self-leadership questionnaire (ASLQ): A more concise measure of self-leadership. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(2), 216-232. [ Links ]

Inam, A., Ho, J.A., Sheikh, A.A., Shafqat, M., & Najam, U. (2021). How self-leadership enhances normative commitment and work performance by engaging people at work? Current Psychology, 5(2),1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01697-5 [ Links ]

Kaiser, H.F. (1970). A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35(4), 401-415. [ Links ]

Karikari, A.S., Kodi, R., & Poku, R.A. (2020). Succession planning as a tool for organizational development: A case study of the University of Education, Winneba Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Review, 3(4), 177-202. https://doi.org/10.37602/IJSSMR.2020.3412 [ Links ]

Leroy, H., Segers, J., Van Dierendonck, D., & Den Hartog, D. (2018). Managing people in organizations: Integrating the study of HRM and leadership. Human Resource Management Review, 28(3), 249-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.02.002 [ Links ]

Li, M., Jameel, A., Ma, Z., Sun, H., Hussain, A., & Mubeen, S. (2022). Prism of Employee Performance Through the Means of Internal Support: A Study of Perceived Organizational Support. Psychology research and behavior management, 15, 965-976. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S346697 [ Links ]

Li, Q., Mohamed, R., Mahomed, A., & Khan, H. (2022). The effect of perceived organizational support and employee care on turnover intention and work engagement: A mediated moderation model using age in the post pandemic period. Sustainability, 14(9125), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159125 [ Links ]

Lowan, V., & Chisoro, C. (2016). Succession planning for business survival: a case of Kwaltita Business Consultants Johannesburg. Kuwait Chapter of the Arabian. Journal of Business and Management Review, 5(12), 63-90. [ Links ]

Løkke, A.-K., & Sørensen, K.L. (2021). Top management turnover and its effect on employee absenteeism: Understanding the process of change. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(4), 723-746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X20931911 [ Links ]

Luedi, M.M. (2022). Leadership in 2022. Best Practice & Clinical Anaesthesiologist, 32(2), 229-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2022.04.002 [ Links ]

Mahfoozi, A., Salajegheh, S., Ghorbani, M., & Sheikhi, A. (2018). Developing a talent management model using government evidence from a large-sized city, Iran. Cogent Business & Management, 5(1), 4-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2018.1449290 [ Links ]

Mistri, A., Patel, C., & Pitroda, J. (2019). Causes, effects and impacts of skills shortage for sustainable construction: A review. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 6(4), 324-335. [ Links ]

Middleton, F. (2019). Reliability and validity: What is the difference? Scribbor. Retrieved from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/reliability-vs-validity/

Nagel, G., & Green, C. (2021). The high cost of poor succession planning. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2021/05/the-high-cost-of-poor-succession-planning

Naidoo, R. (2017). Turnover intentions among South African IT professionals: Gender, ethnicity and the influence of pay satisfaction. The African Journal of Information Systems, 10(1), 1-20. [ Links ]

Oduwusi, O.O. (2018). Succession planning is key to the effective managerial transition process in corporate organizations. American Journal of Management Science and Engineering, 3(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajmse.20180301.11 [ Links ]

Oh, S., & Kim, H. (2019). Turnover intention and its related factors of employed doctors in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142509 [ Links ]

Okwakpam, J.A. (2019). Effective succession planning: A roadmap to employee retention. Kuwait Chapter of the Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 8(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.12816/0055330 [ Links ]

Olufemi, A. (2021). Succession planning: A key to the sustainable family business. Journal of Business and Social Science Review, 2(7), 26-38. [ Links ]

Owolabi, T., & Adeosun, O. (2021). Succession planning and talent retention: Evidence from the manufacturing sector in Nigeria. British Journal of Management and Marketing Studies, 4(1), 17-32. https://doi.org/10.52589/bjmms_xfrracqa [ Links ]

Peters-Hawkins, A.L., Reed, L.C., & Kingsberry, F. (2018). Dynamic leadership succession: Strengthening urban principal succession planning. Urban Education, 53(1), 26-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916682575 [ Links ]

Pila, M.M., Schultz, C.M., & Paul Dachapalli, L. (2015). Factors related to succession planning in a government department in Gauteng. MTech dissertation, Tshwane University of Technology. [ Links ]

Pita, N.A., & Dhurup, M. (2019). Succession planning: Current practices and its influence on turnover intentions in a public service institution in South Africa. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 11(2), 48-64. [ Links ]

Roller, M.R., & Lavrakas, P.J. (2015). Applied qualitative research design: A total quality framework approach. Guilford.

Rosenthall, J., Routch, K., Monahan, K., & Doherty, M. (2018). The holy grail of effective leadership succession planning: How to overcome the succession planning paradox. Deloitte Insights. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4772_Leadership-succession/DI_Succession-planning.pdf

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson.

Stewart, G.L., Courtright, S.H., & Manz, C.C. (2019). Self-leadership: A paradoxical core of organizational behavior. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 47-67. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015130 [ Links ]

Suárez-Albanchez, J., Gutierrez-Broncano, S., Jimenez-Estevez, P., & Blazquez-Resino, J. (2022). Organizational support and turnover intention in the Spanish IT consultancy sector: Role of organizational commitment. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2051790 [ Links ]

Tetteh, J., & Asumeng, A.M. (2020). Succession planning, employee retention and career development programmes in selected organisations in Ghana. African Journal of Management Research (AJMR), 27(1), 151-169. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajmr.v27i1.9 [ Links ]

Thompson, G. (2018). A work in progress, the power of self-acceptance. Retrieved from https://hrdailyadvisor.blr.com/2018/10/09/1-work-in-progress-the-power-of-self-acceptance

Ugoani, J. (2021). Self-leadership and its influence on organisational effectiveness. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 7(2), 38-47. [ Links ]

Uzman, E., & Maya, I. (2019). Self-leadership strategies as the predictor of self-esteem and life satisfaction in university students. International Journal of Progressive Education, 15(2), 78-90. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijpe.2019.189.6 [ Links ]

Wang, Y., Xie, G., & Cui, X. (2016). Effect of emotional intelligence and self-leadership on students' coping with stress. Social Behavior and Personality, 44(5), 853-864. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.5.853 [ Links ]

Winarto, Y., & Chalidyanto, D. (2020). Perceived supervisor support and employee job satisfaction in a private hospital. EurAsian Journal of Biosciences, 14(2), 2793-2797. [ Links ]

Windon, S., Cochran, G., Scheer, S., & Rodriguez, M. (2019). Factors affecting turnover intention of Ohio State University extension program assistants. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(3), 109-127. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.03109 [ Links ]

Wöcke, A., & Barnard, H. (2021). Turnover in South Africa: The effect of history. In D.G. Allen & J.M. Vardaman (Eds.), Global talent retention: Understanding employee turnover around the world (talent management) (pp. 239-259). Emerald Publishing.

Xu, Y., Jie, D., Wu, H., Shi, X., Badulescu, D., Akbar, S., & Badulescu, A. (2022). Reducing employee turnover intentions in tourism and hospitality sector: The mediating effect of quality of work life and intrinsic motivation. International Journal of Environmental Health and Public Health, 19(11222), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811222 [ Links ]

Zulqurnain, A., & Aqsa, M. (2018). Understanding succession planning as a combating strategy for turnover intentions. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 16(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-09-2018-0076 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Cecilia Schultz

schultzcm@tut.ac.za

Received: 11 Apr. 2023

Accepted: 23 Jan. 2024

Published: 07 Mar. 2024