Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Journal of Human Resource Management

versão On-line ISSN 2071-078X

versão impressa ISSN 1683-7584

SAJHRM vol.22 Cape Town 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v22i0.2237

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A supervisor perspective on mental illness in the South African workspace

Kelly De Jesus; Sumari O'Neil

Department of Human Resource Management, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Supervisors have a direct impact on the work experience and outcomes of subordinates living with mental illness; these employees often struggle with consistent employment

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The supervisory role in addressing mental health in the workplace has been explored in terms of the managerial dimension, but not in terms of the supervisor's perceptions and understanding of mental health issues. This study set out to explore and describe supervisors' perceptions of mental illness in the workplace with specific reference to depression, bipolar disorder and anxiety in the South African workplace

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: If supervisors are not aware of the effect of their behaviour and perceptions, reasonable workplace accommodations cannot be successfully made

RESEARCH APPROACH/DESIGN AND METHOD: Data were collected by means of in-depth, semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with 26 junior, middle and senior managers and analysed by means of thematic analysis

MAIN FINDINGS: Organisations in South Africa may not be ready to deal with mental illness in the workplace with supervisors who agree that they are not equipped to deal with mental health issues and their views on mental illness related to common misconceptions and stigmas surrounding it

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Knowledge about mental health conditions within the workplace can assist managers in more effectively recognising, comprehending and implementing people management strategies related to these conditions

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: Owing to the misconceptions of managers, mental wellness in the workplace may not be effectively managed. Better awareness would benefit both managers and HR professionals

Keywords: depression; anxiety; bipolar disorder; mental illness; stigma; leader member exchange; perceived organisational support.

Introduction

Mental illness as a term is used broadly to refer to a collection of mental health issues that are diagnosable and then become 'clinical' when treatment is required (Addington et al., 2019; McRee, 2017). A condition wherein symptoms may satisfy DSM-5 criteria, but are mild and not significantly harmful would not be considered a disorder (Spitzer & Wakefield, 1999). However, Stevenson (2017) proposes that the correct way to view mental health is that we all have mental health, and we oscillate between flourishing, languishing, struggling and being ill. Many adults living with mental illness are active in the workforce (Folmer & Jones, 2018), with a prevalence rate of 12.78% of employees living with mental illness in South Africa in 2019 and one in every six South Africans living with high levels of anxiety and/or depression (Onuh et al., 2021).

Over the years, studies have accumulated evidence pertaining to the importance of supervisor's perceptions and the effect of these perceptions on an employee's mental health (Gayed et al., 2018; Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2004). Themes related to how supervisors perceive their role in addressing workplace mental health challenges have been extensively investigated (Brimhall et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the current body of research predominantly focuses on the managerial aspects, leaving a research void when it comes to understanding supervisors' perspectives on particular mental health issues.

Next follows a literature review that provides the necessary context and background information, helping readers to understand the existing body of knowledge in the field of mental health issues and the workplace with specific reference to depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder.

Literature review

Mental illnesses account for 4 of the 10 leading causes of disability globally and are said to be more debilitating than chronic physical illness (Grande et al., 2016). In the workplace, it may have a direct impact on the organisation through employee absenteeism, lower levels of productivity and high healthcare costs (MacDonald-Wilson et al., 2002). Addressing employees' mental health challenges and the accompanying stigma frequently falls to supervisors, who are critical role-players in inducing employment pathways and a positive social climate (Kirsh et al., 2018). It is therefore highly likely, regardless of the industry, that supervisors in the workplace will encounter an employee who is living with a mental illness during their career.

Depression, high levels of anxiety and bipolar disorder are of great concern to South African organisations. Globally, depression is considered a major cause of disability (Stander et al., 2016). In South Africa, 9.7% of the adult population is diagnosed with lifetime depressive disorder with 90% of those diagnosed reporting role impairment (Tomlinson et al., 2009). More recent studies report higher prevalence of depressive disorders, with Stander et al. (2016) reporting that more than 25% of the South African working population have 'suffered from one or more episodes of clinically diagnosed depression' (p. 7), and Welthagen and Els (2012) reporting from their sample that 18.3% of adults receive medical treatment for depressive disorders.

Depression and anxiety are especially relevant in the current climate and times in South Africa. As reported by Heywood (2021:1):

South Africa is now facing a mental health emergency that is the culmination of simultaneous crisis that are imploding the hopes, dreams and dignity of many who live in the country: the Covid crisis, the unemployment crisis, the inequality crisis, the femicide crisis, the poverty crisis.

Although slightly less prevalent, Stein et al. (2008) estimated that 15.8% of the South African adult population live with high levels of anxiety. More than 1% of the general population worldwide live with bipolar disorder, and a significant portion of individuals with this condition, representing at least half of them, lack consistent employment (Marion-Paris et al., 2023). In the following section, depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder will briefly be explained.

Depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder

Depression is the most common mental health problem worldwide (McIntyre & O'Donovan, 2004). Depression implies a reduction in a person's capacity for, or interest in, pleasure or even mild enjoyment of everyday activities. Increased irritability and apathy may be noticeable and physical complaints are likely (Alexander et al., 2007). In severe cases of depression, people may not be able to carry out self-care.

Anxiety is an intense fear of being socially scrutinised in interpersonal situations (Attridge, 2008). Although anxiety is classified by DSM-5 as a category of mental illness on its own, it is often a symptom of other mental illnesses and a commonly found comorbid mental illness. Anxiety is a dynamic concept as it can be found throughout the mental health and/or mental illness continuum even in moderate levels at a so-called normal level of functioning. The relevance of anxiety here was the rate of comorbidity to mental illnesses as anxiety is often comorbid with various mood disorders. Over time, many of those who live with high levels of anxiety are likely to develop comorbid depression (Jacobson & Newman, 2017). The most common comorbidity pairings are bipolar disorder and anxiety, and depression and anxiety (Attridge, 2008; Inoue et al., 2020).

Bipolar disorder is characterised by bipolar I, associated with variations in mood that swing from an extremely high mood (known as manic episodes associated with significant psychosocial impairment) or bipolar II to an extremely low mood (associated with both hypomanic and depressive episodes) (Tokumitsu et al., 2023). In DSM-5, bipolar and related disorders are not affiliated with depressive disorders. They are positioned between the sections on the schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders on the one hand and depressive disorders on the other. This acknowledges their place as a conduit between the two diagnostic classes in terms of symptomatology, family history and genetics (APA, 2013). This suggests that while bipolar is not categorised as a depressive disorder, it does not fall in the range of psychotic disorders either, but rather exists as a spectrum between these two classifications. Bipolar disorder is however often confused with depression and in itself may not receive a lot of attention in research studies, especially in South Africa (Esan & Esan, 2016; Grande et al., 2016). Montejano et al. (2005) describe the nature of the condition by using its alternative name: manic-depressive disorder. People who live with this disorder cycle through episodes of extreme sadness and intense euphoria (in other words, depressive and manic episodes) (Montejano et al., 2005).

Mental illness in the workplace

Research on mental health in the workplace have highlighted the economic impact of poor mental health on organisations through direct and indirect costs (Taubman & Parikh, 2023). However, successful inclusion of employees living with mental illness may hold many benefits to both the organisation and the employee (Hennekam et al., 2020). On an individual level, unemployment has significant negative effects on mental health (Posel et al., 2021). Sustained employment, however, carries many advantages, including financial independence, providing a platform for social interaction, enabling one to contribute to society and giving a meaning and purpose in life (Boot et al., 2015; Vooijs et al., 2018). On an organisational level, the employee living with mental illness may contribute uniquely to the workforce (Wiklund et al., 2018) with levels of productivity being similar to or even higher than workers not living with mental health issues (Pelham & Boninger, 2020).

An important factor affecting the successful inclusion of employees living with a mental illness is the work environment and the reaction of the workplace towards those employees (Breedt et al., 2023; Brouwers et al., 2020; Dimoff & Kelloway, 2019). In this study, the focus is on the effect of leadership behaviour specifically. Leadership is an important factor that can either improve or negatively impact employees' mental health and well-being (Kelloway et al., 2023). Negative leadership behaviour such as abusive supervision is linked to negative outcomes (such as exhaustion, physical symptoms, job dissatisfaction, intention to quit and poor job performance) for employees (Pyc et al., 2017). Brouwers (2020) points to negative attitudes of leaders as a barrier towards the successful workplace inclusion of people living with mental illness.

While negative leadership behaviours can be detrimental to the mental health of employees, positive and constructive leadership can be supportive and facilitate better work performance (Pelham & Boninger, 2020). Positive leadership behaviours provide resources to the employees that allow them to cope with the work challenges and stressors (Dimoff & Kellaway, 2020); moreover, the relationship between the leader and the employee living with mental illness creates a supportive workplace (Nielsen et al., 2017) which in turn is important for the overall functioning of the employee living with mental illness (De Oliveira et al., 2023).

Supervisor-subordinate relationships with a specific focus on supervisor perception

The importance of focussing on supervisor perceptions of mental illness of their subordinate employees in this study is grounded in two theoretical standpoints: leader member exchange (LMX) theory (Wayne et al., 1997; Winkler, 2010) and perceived organisational support (POS) (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). From an LMX perspective (Dansereau et al., 1975; Graen et al., 1982), the dyadic relationship between the leader and subordinate has a direct influence on subordinate behaviour (Bauer & Erdogan, 2015). The supervisor will develop a different relationship with each employee based on their interaction.

The quality of the relationships is often categorised as high-, medium- and low-quality exchanges, with the high-quality exchanges being beneficial to both the organisation and the subordinate (Van Breukelen et al., 2006). High-quality relationships are characterised by higher levels of supervisor support and guidance and lead to higher work satisfaction and performance of the subordinates (Colella & Varma, 2001). High-quality LMX has also shown to positively impact health and well-being outside the organisation (Gregory & Osmonbekov, 2019). Studies within the organisational context have also shown that that high-quality LMX acts as a buffer against psychological health issues at work (Schermuly & Meyer, 2015).

In terms of this study, the LMX theory highlights the importance of a supervisor's behaviour on the relationship between the leader and subordinate, as well as the behavioural outcomes of the subordinate (Van Breukelen et al., 2006). Leader and subordinate attributes have been found to impact the exchange quality (Nahrgang & Seo, 2015). Subordinate's attributes include their competence and skills to fulfil their roles in the workplace, and more important for this study is the fact that supervisor's perceptions of subordinate skills and ability to fulfil their duties have an impact on the quality of the supervisor-subordinate relationship (Brouwers, 2020). In fact, expected subordinate performance can have a greater impact on the quality of the exchanges than actual behaviour (Taubman & Parikh, 2023).

Perceptions of performance of subordinates living with mental illness may be clouded with stigma (Folmer & Jones, 2018). Stigmatisation is a process by which persons are undervalued and estranged from certain social exchanges because they are believed to possess characteristics, such as age, gender or medical conditions, which are perceived as undesirable in certain scenarios (Summers et al., 2018). Stigmas related to employees with mental health issues are that they do not function optimally and are not able to fulfil their role in the workplace effectively (Folmer & Jones, 2017). They are perceived to be unstable, crazy, incompetent or even dangerous (Corrigan et al., 2005).

Stigma has both an indirect and a direct negative effect on employee work performance. Indirect stigma is found in the unfair application of sickness absence policies (Sallis & Birkin, 2013) and the restriction on personal growth and development opportunities (Fox et al., 2016). Stigmatised views held by supervisors will lead to low LMX, as stigma is based on assumptions about the subordinate's competence and behaviour in the workplace (Krupa et al., 2009). The tendency is to have lower expectations for subordinates living with mental illnesses at work (Porter et al., 2019).

Mental illness is also often seen as a less legitimate condition (Folmer & Jones, 2018). This may in part be the reason for subordinates to conceal their mental illness (Peterson et al., 2017). Rai (2009) postulates that the subordinate will use impression management and integration as tactics to conceal their mental illness from the supervisor. It should be noticed however that in high-quality relationships that are characterised by trust, respect and exchange of resources, subordinates are more willing to disclose their mental illness and associate the disclosure with less risk (Westerman et al., 2017).

When subordinates do not disclose their diagnosis of mental illness, they face the risk of being adversely affected thereby, as they are usually unable to receive proper medical treatment (Dewa et al., 2011) and cannot be adequately supported by the organisation (Dewa & Hoch, 2015). Without proper treatment and support, the adverse effects that the mental illness may have on the organisation (such as reduced impairment and loss of productivity) may increase (Nielsen et al., 2017). Keeping the symptoms of depression, high levels of anxiety or bipolar disorder, a secret may also have other implications, such as detachment from social relationships or lessened self-esteem, that further limit work opportunities (Ray & Dollar, 2014).

Perceived organisational support focuses on the relationship between employees and the organisation and theorises that to satisfy socioemotional needs and to ascertain the organisation's willingness to reward amplified work effort, employees develop beliefs about the degree to which the organisation values their contributions (Eisenberger et al., 2020). As an extension of this, employees also develop beliefs about the extent to which the organisation is concerned for their well-being (Suifan et al., 2018). More specifically, a positive relationship exists between POS and employee well-being (Kurtessis et al., 2017).

Supervisors are directly involved in employees' POS as they act as representatives of the organisation (Eisenberger et al., 2020). As pointed out by Taubman and Parikh (2023), the supervisor is directly involved with the employees and will therefore have a privileged information about the challenges and opportunities the employees face. Supervisors also have direct impact on the work environment through an ability to provide support to the employee (Harunavamwe & Ward, 2022). Supervisor support acts as a resource that helps employees cope with workplace adversities and stress (Kelloway et al., 2023). From this perspective, studies focus on how supervisors manage employees with mental disorders (Bubonya et al., 2017; Dimoff & Kelloway, 2019). For example, Brimhall et al. (2017) found themes that relate to perceptions of the supervisory role relative to managing mental health problems at the workplace. While studies like these are vital in analysing how supervisors manage mental health issues at work, their focus is on the managerial aspect, not the supervisor's understanding of the mental health issues concerned. This study will focus specifically on the perceptions of the supervisors about the mental illness of their subordinates. This is significant, especially because previous studies emphasise the detrimental effects of misconceptions about mental illness (Brouwers, 2020; Stuart, 2006). Misconceptions about depression, bipolar disorder and high levels of anxiety in the workplace, as well as the stigma associated with them, have negative outcomes for all stakeholders (Byrne, 2000; Corrigan, 2002).

The purpose of the study

This study aims to shed light on mental health in the workplace by focussing specifically on the perceptions of supervisors. The perception of mental illness held by supervisors has a direct impact on the relationship between the supervisor and the subordinate (Folmer & Jones, 2018). This relationship in turn affects the work experience and outcomes of the worker with a mental illness (Huang & Simha, 2018). It is therefore important to understand how supervisors view mental illness and their expectations of the work performance of subordinates who may live with these conditions. The purpose of this study was to explore and describe how South African supervisors perceive subordinates who live with mood disorders, specifically depression and bipolar disorder and high levels of anxiety and what behaviour they expect of them in the workplace.

Research design and method

Research approach and strategy

As the focus of this study was on human experiences and perception, a qualitative methodology, using a phenomenological design, was employed as it allows for a focus on the human experience (Rutberg & Bouikidis, 2018).

Research participants and sampling

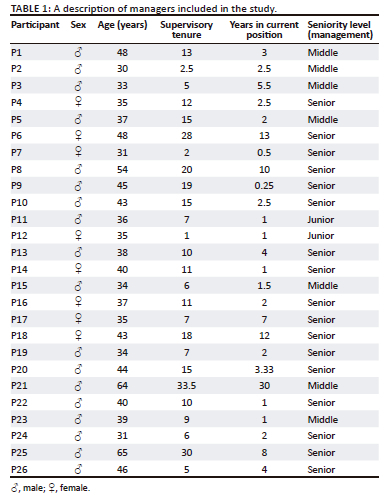

This study combined non-probability purposive and snowball sampling techniques. Twenty-six participants (8 female, 18 male) were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: they needed to hold a position of management in a white-collar workplace in South Africa. All participants worked and lived in the Gauteng province. Participants from the first author's own network were first approached. Some referrals from friends who knew about the study were also followed up, as well as referrals from participants themselves.

The age of the participants ranged from 30 to 65 years, with an average age of 41 years. The tenure of supervisory experience ranged between 1 and 33.5 years, with the average being 12.8 years. Most of the participants were senior managers (n = 17); seven were middle managers and two were junior managers. See Table 1 for a summary of the participant particulars.

Data collection methods

Data were collected by means of semi-structured, face-to-face interviews between 29 November 2018 and 13 February 2019. Written informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the interview. The interview guide covered various topics including the participants' general experience with mental illness, supervisor-subordinate dynamics, and how it is affected by mental illness of the employee, workplace culture and its inclusion of mental illness. Additional topics that were covered are the personal experiences of managing people with mental illness if any existed, expectations of disclosure, workplace absence and functioning of employees who live with mental illness, as well as experiences of stigma related to mental illness.

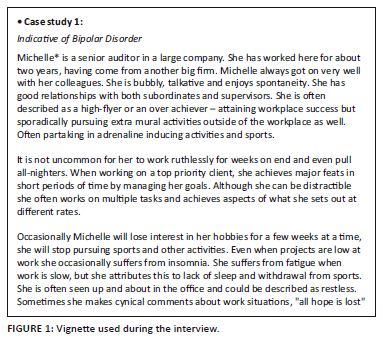

The interviews used five vignettes per interview as an elicitation method (Arghavanian et al., 2020). These were designed specifically for this study, with content based on the DSM-5 descriptions of the behaviour expected from the different illnesses, including depression, high levels of anxiety and bipolar disorder (see an example in Figure 1). The three main questions on the vignettes were: What would your next steps be with the employee in the scenario? Do you believe the scenario is situational or indicative of an illness? If indicative of an illness, which one?

The interviews ranged between 25 min and 80 min, with an average of 53 min. Although an interview guide was used, managers were encouraged to talk freely about their experiences and perceptions related to mental illness.

Data recording

With the permission of the participants, the interviews were recorded, which allowed the researchers to check the accuracy of the transcriptions. Minimal note taking took place during the interviews to ensure that the interviewer listened actively.

Strategies employed to ensure data quality and integrity

The interview questions were derived from a thorough literature review (Wagner et al., 2012). The accuracy of the data was ensured by recording the interviews and cross-checking transcriptions. Sample sufficiency was ensured by employing purposive sampling (Morse et al., 2017). In terms of observer bias, we worked as two researchers from different contexts - one in academia and one in a corporate environment. During the process of data collection and data analysis, peer debriefings were held to ensure the accuracy in translating the experiences of the participants. This was also a measure to improve neutrality, which in turn improves the trustworthiness of qualitative studies (Daniel, 2019). To ensure limited bias because of social desirability on the participants, the interviewer ensured that rapport was established before the interview (Bergen & Labonté, 2020).

Data analysis

Statements from transcriptions that answered the research question were coded by means of open coding using Atlas.ti 8 (Leedy & Ormrod, 2014). Overall, 37 codes were identified through various cycles of coding. These codes were grouped into nine subthemes, with three overarching themes emerging from the data: supervisor perceptions of mental illness, the perceived effects of mental illness in the workplace, and empathy for employees living with mental illness.

Results

The findings are shown per theme and subtheme. Verbatim data are used to contextualise the findings in the data. Themes 1 and 2 were derived directly from the verbatim data, while theme 3 emerged unsuspectedly during the data analysis upon our realisation that the managers showed different levels of compassion towards employees living with mental illness. The results of this analysis are shown differently to reflect the analysis used.

Theme 1: Supervisors' perception of depression and high levels of anxiety

During the interviews, the supervisors were asked where they believed the mental illness originated and how it can be treated. These responses are reported under subthemes 1.1 and 1.2. It was evident from the data that there were many misconceptions that clouded the supervisors' view on the mental illnesses. These misconceptions are reported under subtheme 1.3.

Subtheme 1.1: Origins of mental illness

The participant's views of the origins of mental illness were that it is: (1) a chemical imbalance, (2) genetically inherited, (3) a developmental attribute or learned behaviour, (4) part of one's personality characteristic, (5) due to external circumstances and (6) a comorbidity of another mental illness (see Table 2 for verbatim extracts of each origin).

Subtheme 1.2: Treatment for mental illness

The supervisors also had different views about how the illnesses should be treated; it was clear that most (15 of the participants) agreed that treatment is essential, regardless of the type of treatment. Treatment options included were medication, lifestyle changes and therapy.

Subtheme 1.3: Misconceptions about mental illness

Most (22 of the participants) perceptions of mental illness were aligned with common misconceptions, including that: (1) mental illness is passion or work ethic; (2) stress or burnout is a form of mental illness; (3) mood shows personality and (4) high levels of anxiety as less substantial than other illnesses (see Table 3 for verbatim extracts).

Theme 2: The perceived effects of mental illness in the workplace

The second major theme emerged from the data related to the supervisors' views about how subordinates will function in the workplace. In these data, we distinguished between reference to the organisation's response to the employee living with a mental illness and the participant's view on how the employee will function in the workplace.

Subtheme 2.1: Supervisors' opinions about their workplace readiness related to mental illness

In general, it seemed as though the participants agreed that the South African workplace is not ready to deal with employees who live with mental illness and that there should be reform in this regard, including formal workplace training. One participant found the need for workplace reform around the topic:

'the awareness in the workplace really needs to be heightened.' (P23)

Another participant noticed that the lack of awareness is because of a lack of training:

'I didn't read about it. I didn't do industrial psychology in varsity - or whatever it is. You know what I mean, I actually picked it up as I went along. You know, and like I said if it was taught to me, I would've known about it. But I didn't know about it.' (P1)

Table 4 shows in more detail the data extracts for each of the opinions of supervisors' workplace readiness related to mental illness as observed by the participants.

Related to the theme of ignorance or lack of knowledge, the participants agreed that in general views about mental illness are stigmatised. With specific reference to disclosure, one participant said:

'I think that the person (who disclose their mental illness) is immediately seen as unreliable and that they can't be trusted with clients and that they can't be trusted with big accounts.' (P19)

Participant 4 echoed this in saying: 'Uhm, in the workplace it (disclosing and living with a mental illness) does hamper your ability to be promoted I am 100% certain of that.' This particular participant indicated that she or he actively discouraged disclosure owing to the different treatment an employee may receive:

'… I've cautioned individuals, not to disclose on official record. That it [absence] is as a result of mental illness, but they have disclosed to me that it [absence] is as a result of mental illness. I have cautioned individuals not to submit a doctor's note necessarily in that regard …' (P4)

In the discussion the participants referred to the stigma in the organisation in general. However, stigmatised views were also visible in how the participants themselves referred to employees living with mental illness during the interviews. For example, participant 25 said:

'Let's just be blunt and say it. People with depression are useless workers or you can't trust them. They are not reliable. They shouldn't be in the workplace.' (P25)

Furthermore, the participants' own language about people living with mental illness indicated stigmatisation in their choice of derogatory words when referring to mental illness. For example, when referring to people living with high levels of anxiety disorder, participant 9 said:

'She's an high levels of anxiety freak. Or uh, no not a freak. You know somebody that suffers from … Ja, that's highly strung or very anxious …' (P9)

This participant said:

'So, its people that for no good reason, whether there is a little bit of stress or just something that they experience as stressful. And they become extremely anxious, and they get heart palpitations, and they just go bonkers.' (P10)

Subtheme 2.2: Data extracts for perceptions of workplace performance of employees with a history of mental illness

When asked directly, it was evident that the supervisors perceived employees with a history of mental illness to have workplace performance either better than or the same as other employees. Only one participant said that the performance of employees who live with a mental illness may be worse (see Table 5). The majority opinion of 15 of the participants was that employees with well-managed mental illness perform the same or better than average. Seven of the participants believed that these employees would perform better than average. This level of performance can however only be attained if the employee living with mental illness receives treatment and the condition is well managed.

Important to the perceived workplace performance, supervisors explained that performance and work behaviours depended on the individual employee and the specific illness - to be determined on a case-by-case basis in the workplace. A participant, for example, said:

'The link between performance and mental illness - there is no direct link. Sometimes there is a direct link, sometimes there is no link. […] It depends on a case-by-case situation. And it depends on the individual.' (P8)

Without proper treatment, the supervisors were confident that the employee living with the mental illness will not be able to perform adequately in the workplace. For example, this participant observed that:

'So, she completely lost like went ballistic in the office. It was the smallest thing. She received an email from myself and it tripped her off completely. And it was because she was, - her meds didn't come through and she wasn't on her meds.' (P11)

Theme 3: Supervisor empathy for subordinates living with a mental illness

During the analysis it was evident that participants' reactions and answers to questions could be categorised on a continuum from high and low empathy shown (Figure 2). For the purposes of this study, empathy is 'to understand, feel and share what someone else feels, with self-other differentiation' (Håkansson Eklund & Summer Meranius, 2021, p. 306). In the analysis, the number of times empathetic language was used to refer to people living with mental illness was tallied. This included non-verbal reactions that conveyed compassion or emotional understanding (such as crying), directly indicating that an experience gave them more compassion and using variations of words such as 'empathy' and 'sympathy'.

Nineteen of the participants mentioned empathy in some way. These participants all had experience with mental illness either in a personal capacity, by knowing a family member or friend who lived with mental illness. It was noticeable from our analysis that those participants with no experience did not show or mention empathy for employees living with mental illness during the interview.

When asked how their experiences influenced their perceptions as supervisors, the participants said that it enabled the participants to manage people living with the illness. For example, a participant said:

'Oh, for sure. Yes, its ah [chuckles] unfortunate. That I had to go through personal depression before I could understand it. But ja, it definitely opened my eyes to a lot of things. And I see it more clearly now - because I see for those signs.' (P1)

The experience created not only an ability to recognise symptoms but also allowed a deeper level of understanding on how to react to it. This is evident in the words of a participant:

'Yes, they do, they allow me to sympathise far more than I probably would have. It has allowed me to understand to really understand what people go through. Because obviously my personal experiences, have resulted in, people in my family, sharing very openly with me what it feels like. So, I understand from - if you are seriously depressed and you don't have the help.' (P4)

It was interesting in the data that personal experience as opposed to knowing or living with someone with a mental illness allowed greater understanding. As a participant said:

'I've got friends who have depression. Who take medication. Who deal with things differently. I don't understand it because I've never. But if you are asking understanding, I don't understand it because I've never had the illness myself.' (P7)

Discussion

Hamann et al. (2016) noticed that perceptions of depression and anxiety in the workplace is often grounded in a lack of knowledge about it. This was evident from the data in this study. Although supervisors' experience and knowledge varied, their perceptions were often built on misconceptions rather than facts. Misconceptions are usually related to stigmatised views of mental illnesses at work (Stuart, 2006), for example, that workers with mental illness are unreliable workers - a view also held by some of the participants in this study. As such, the result in our study reiterates the fact that perceptions are focussed on what goes wrong at work with low-level performance easily being attributed to mental illness (Brouwers, 2020). This is further extrapolated to the organisation, which according to the participants in our study are not equipped for dealing with employees living with mental illness because of the commonly held views about negative workplace behaviour.

Our results further showed that stigmatised views may be unconscious on the part of the managers. Some supervisors said during the interview that they did not have any objection against employees who live with mental illness in the workplace. In fact, only one manager perceived workplace performance of those living with mental illness to be below a standard of what can be expected by a healthy employee. However, it was clear from their choice of words in describing mental illness or employees who suffer from mental illness that this may not be the case. Their word choice had derogatory connotations, albeit unintentionally (Holley et al., 2016). Some direct quotes include words such as 'freak', 'bonkers' and 'koekoes'.

Supervisors' perceptions of the mental illness as well as their own ability to effectively manage employees living with mental illness in the workplace was influenced by their personal experience, either personally living with a mental illness or having a friend or family member who lives with a mental illness. In our study, only the supervisors who had some personal experience with mental illness showed compassion or empathy for the employee living with it. Individuals with higher levels of empathy (Jeffrey, 2016) by means of previous experience with mental illness (their own, personal or professional) are better equipped to deal with mental illness in the workplace.

The exchange relationship between supervisor and subordinate may be highly influenced where the supervisor acts with compassion because of an empathetic stance (Baral & Sampath, 2019; Sampath et al., 2020). Superior exchange relations between the supervisor and employee also have an impact on perceived organisational inclusion (Brimhall et al., 2017). The presence of empathy could be the difference between deciding to seek help and suffering further mental health deterioration (Furnham & Sjokvist, 2017). As shown in the literature review, POS is essential in disclosure of living with a mental illness in the workplace (Folmer & Jones, 2018; Westerman et al., 2017).

Practical implications

Training interventions will equip supervisors with the knowledge and skills to properly support those who are affected (Gayed et al., 2018). More extensive and compulsory training for all HR professionals is needed about mental illness in the workplace, including HR managers. This is important because the data showed that managers perceived mental illness to be an HR issue, and thus HR personnel need to be equipped to guide supervisors.

Following the misconceptions within the supervisor's views, as well as their mention of their own ignorance regarding the management of mental illness in the workplace, managers should be expected to attend training on mental illness awareness during their management tenure. This will not only assist managers with their duties but also create an environment where employees who live with mental illness are seen as an important part of the workforce that needs assistance. The fact that manager perceptions are based on misconceptions implies that training is knowledge-focussed and provides accurate information on workplace mental illness, which can debunk common misconceptions regarding employees who live with mental illness.

Limitations and recommendations

Several limitations exist in the context of this study. The interviews were conducted in English. In a country with 11 official languages, it is possible that some participants would have preferred to be interviewed in their home language and hence been able to give more in-depth answers. However, this does not necessarily negate the findings. Some participants were invited to answer in the interviewer's second language, Afrikaans, but chose to answer in English instead.

The purposive sampling and snowball sampling used to select the participants for this study yielded a sample that is not representative of supervisors in South African business activities in general. Eighteen (70%) of the participants were men. Future studies can focus on or include more females for the purpose of comparison. The recruitment strategy, while practical and effective in the context of this research, also presents a potential limitation in terms of sample diversity (Marcus et al., 2017).

To address this limitation and enhance the applicability of future qualitative studies, researchers are encouraged to employ a broader recruitment strategy. While personal networks and referrals can provide valuable insights (Parker et al., 2019), a more diverse sample can be obtained by using multiple recruitment channels. These may include university campuses, online communities, professional organisations and public advertisements. By casting a wider net during recruitment, researchers can access a more diverse range of perspectives and experiences, leading to richer and more comprehensive qualitative data.

In terms of ethnic diversity, the study consisted of predominantly white and Indian individuals. Almost all participants are employed in the Johannesburg area with a minority employed in Pretoria. The sample therefore represents a particularly urban subset of the relevant South African population, and the findings cannot be generalised to the larger population of South African workers.

The vignettes were not pilot-tested and validated before the study. One reason for this was that vignettes of this nature are not readily available, and they were created specifically for the study. To ensure that the scenarios were close to actual workplace behaviour that reflect the different mental illnesses, they were written with key components directly extracted from DSM-5.

The data were collected from 2018 to 2019. With this time lapse to this publication, the managerial and organisational context may have changed. However, in the dawn of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been an increase in mental illness in the workplace (Posel et al., 2021) with stigma still being prevalent in organisations (Taubman & Parikh, 2023).

Conclusion

This study highlighted the views of supervisors regarding employees living with mental illness. Generally, participants felt that the workplace is ill-equipped for mental illness. Although some supervisor knowledge was DSM-5-specific and all spoke of various forms of necessary treatment, all supervisors relayed beliefs that overlap with common misconceptions. None of the participants felt prepared to handle manifestations of mental illness in the workplace, although all were in management and were leaders and supervisors in their respective fields. This highlights the importance of training to both managers and HR professionals in this regard.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

K.D.J. was responsible for the data collection, data analysis and drafting the article. S.O. was responsible for drafting and evaluating the article and data analysis.

Ethical considerations

The project was approved by the Institutional Research Committee. Ethical clearance number: EMS166/18.

Funding information

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

Data for this article will be made available on the data repository of the University of Pretoria.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Addington, J., Liu, L., Goldstein, B., Wang, J., Kennedy, S., Bray, S., Lebel, C., Stowkowy, J., & MacQueen, G. (2019). Clinical staging for youth at-risk for serious mental illness. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(6), 1416-1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12786 [ Links ]

Alexander, J., Keita, G., Toney, S., & Golinkoff, M. (2007). Shrinking health care disparities in women: The depression dilemma. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, 13(9 Suppl. A), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.9-a.1 [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Author.

Arghavanian, F.E., Heydari, A., Bahmani, M.N.D., & Roudsari, R.L. (2020). An account of Iranian pregnant women' experiences of spousal role: An ethnophenomenological exploration. Journal of Midwifery & Reproductive Health, 8(4), 2404-2418. [ Links ]

Attridge, M. (2008). A quiet crisis: The business case for managing employee mental health (pp. 1-17). PROACT & Wilson Banwell Human Solutions. Retrieved from http://healthyworkplaces.info/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/HS_annual_2008_EN.pdf

Baral, R., & Sampath, P. (2019). Exploring the moderating effect of susceptibility to emotional contagion in the crossover of work-family conflict in supervisor-subordinate dyads in India. Personnel Review, 48(5), 1336-1356. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-05-2017-0139 [ Links ]

Bauer, T.N., & Erdogan, B. (2015). The Oxford handbook of leader-member exchange (Oxford Library of Psychology) (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

Boot, C.R., De Kruif, A.T., Shaw, W.S., Van der Beek, A.J., Deeg, D.J., & Abma, T. (2015). Factors important for work participation among older workers with depression, cardiovascular disease, and osteoarthritis: A mixed method study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26(2), 160-172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-015-9597-y [ Links ]

Breedt, J., Marais, B., & Patricios, J. (2023). The psychosocial work conditions and mental well-being of independent school heads in South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 21, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v21i0.2203 [ Links ]

Bergen, N., & Labonté, R. (2020). "Everything is perfect, and we have no problems": Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 30(5), 783-792. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319889354 [ Links ]

Brimhall, K.C., Mor Barak, M.E., Hurlburt, M., McArdle, J.J., Palinkas, L., & Henwood, B. (2017). Increasing workplace inclusion: The promise of leader-member exchange. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership &Amp; Governance, 41(3), 222-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2016.1251522 [ Links ]

Brouwers, E., Joosen, M., Van Zelst, C., & Van Weeghel, J. (2020). To disclose or not to disclose: A multi-stakeholder focus group study on mental health issues in the work environment. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 30(1), 84-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09848-z [ Links ]

Brouwers, E.P.M. (2020). Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: Position paper and future directions. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00399-0 [ Links ]

Bubonya, M., Cobb-Clark, D.A., & Wooden, M. (2017). Mental health and productivity at work: Does what you do matter? Labour Economics, 46, 150-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.05.001 [ Links ]

Byrne, P. (2000). Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6(1), 65-72. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.6.1.65 [ Links ]

Colella, A., & Varma, A. (2001). The impact of subordinate disability on leader-member exchange relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 304-315. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069457 [ Links ]

Corrigan, P.W. (2002). Empowerment and serious mental illness: Treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatric Quarterly, 73(3), 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016040805432 [ Links ]

Corrigan, P.W., Kerr, A., & Knudsen, L. (2005). The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11(3), 179-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appsy.2005.07.001 [ Links ]

Daniel, B.K. (2019, June). What constitutes a good qualitative research study? Fundamental dimensions and indicators of rigour in qualitative research: The TACT framework. In Proceedings of the European conference of research methods for business & management studies (pp. 101-108), Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dansereau, F., Graen, G., & Haga, W.J. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making process. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13(1), 46-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(75)90005-7 [ Links ]

De Oliveira, C., Saka, M., Bone, L., & Jacobs, R. (2022). The role of mental health on workplace productivity: A critical review of the literature. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 21(2), 167-193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00761-w [ Links ]

Dewa, C.S., & Hoch, J.S. (2015). Barriers to mental health service use among workers with depression and work productivity. Journal of Occupational &Amp; Environmental Medicine, 57(7), 726-731. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0000000000000472 [ Links ]

Dewa, C.S., Thompson, A.H., & Jacobs, P. (2011). Relationships between job stress and worker perceived responsibilities and job characteristics. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2(1), 37-46. [ Links ]

Dimoff, J.K., & Kelloway, E.K. (2019). With a little help from my boss: The impact of workplace mental health training on leader behaviors and employee resource utilization. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000126 [ Links ]

Esan, O., & Esan, A. (2016). Epidemiology and burden of bipolar disorder in Africa: A systematic review of data from Africa. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(1), 93-100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1091-5 [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500 [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R., Rhoades Shanock, L., & Wen, X. (2020). Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7, 101-124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917 [ Links ]

Folmer, K.B., & Jones, K.S. (2017). Mental illness in the workplace: An interdisciplinary review and organizational research agenda. Journal of Management, 44(1), 325-351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317741194 [ Links ]

Fox, A.B., Smith, B.N., & Vogt, D. (2016). The Relationship between anticipated stigma and work functioning for individuals with depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(10), 883-897. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2016.35.10.883 [ Links ]

Furnham, A., & Sjokvist, P. (2017). Empathy and mental health literacy. HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice, 1(2), e31-e40. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20170328-01 [ Links ]

Gayed, A., Milligan-Saville, J.S., Nicholas, J., Bryan, B.T., LaMontagne, A.D., Milner, A., Madan, I., Calvo, R.A., Christensen, H., Mykletun, A., Glozier, N., & Harvey, S.B. (2018). Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 75(6), 462-470. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104789 [ Links ]

Graen, G., Novak, M.A., & Sommerkamp, P. (1982). The effects of leader - Member exchange and job design on productivity and satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 30(1), 109-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(82)90236-7 [ Links ]

Grande, I., Berk, M., Birmaher, B., & Vieta, E. (2016). Bipolar disorder. The Lancet, 387(10027), 1561-1572. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00241-x [ Links ]

Gregory, B., & Osmonbekov, T. (2019). Leader-member exchange and employee health: An exploration of explanatory mechanisms. Leadership &Amp; Organization Development Journal, 40(6), 699-711. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-11-2018-0392 [ Links ]

Håkansson Eklund, J., & Summer Meranius, M. (2021). Toward a consensus on the nature of empathy: A review of reviews. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(2), 300-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.022 [ Links ]

Hamann, J., Mendel, R., Reichhart, T., Rummel-Kluge, C., & Kissling, W. (2016). A "Mental-Health-at-the-Workplace" educational workshop reduces managers' stigma toward depression. Journal of Nervous &Amp; Mental Disease, 204(1), 61-63. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000000423 [ Links ]

Harunavamwe, M., & Ward, C. (2022). The influence of technostress, work-family conflict, and perceived organisational support on workplace flourishing amidst COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 921211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921211 [ Links ]

Hennekam, S., Richard, S., & Grima, F. (2020). Coping with mental health conditions at work and its impact on self-perceived job performance. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(3), 626-645. https://doi.org/10.1108/er-05-2019-0211 [ Links ]

Heywood, M. (2021, October 12). South Africa's mental health epidemic: Love don't live here anymore. Daily Maverick. Retrieved from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-10-12-south-africas-mental-health-epidemic-love-dont-live-here-anymore/

Holley, L.C., Tavassoli, K.Y., & Stromwall, L.K. (2016). Mental illness discrimination in mental health treatment programs: Intersections of race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(3), 311-322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-9990-9 [ Links ]

Huang, C.S., & Simha, A. (2018). The mediating role of burnout in the relationships between perceived fit, leader-member exchange, psychological illness, and job performance. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(Suppl. 1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000077 [ Links ]

Inoue, T., Kimura, T., Inagaki, Y., & Shirakawa, O. (2020). Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders and their associated factors in patients with bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 1695-1704. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s246294 [ Links ]

Jacobson, N.C., & Newman, M.G. (2017). Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1155-1200. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000111 [ Links ]

Jeffrey, D. (2016). Empathy, sympathy and compassion in healthcare: Is there a problem? Is there a difference? Does it matter? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 109(12), 446-452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076816680120 [ Links ]

Kelloway, E.K., Dimoff, J.K., & Gilbert, S. (2023). Mental health in the workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 363-387. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-050527 [ Links ]

Kirsh, B., Krupa, T., & Luong, D. (2018). How do supervisors perceive and manage employee mental health issues in their workplaces? Work, 59(4), 547-555. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-182698 [ Links ]

Kurtessis, J.N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M.T., Buffardi, L.C., Stewart, K.A., & Adis, C.S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of management, 43(6), 1854-1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554 [ Links ]

Krupa, T., Kirsh, B., Cockburn, L., & Gewurtz, R. (2009). Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work, 33(4), 413-425. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-2009-0890 [ Links ]

Leedy, P., & Ormrod, J. (2014). Practical research planning and design (10th ed.). Pearson.

MacDonald-Wilson, K.L., Rogers, E.S., Massaro, J.M., Lyass, A., & Crean, T. (2002). An investigation of reasonable workplace accommodations for people with psychiatric disabilities: Quantitative findings from a multi-site study. Community Mental Health Journal, 38, 35-50. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013955830779 [ Links ]

Marcus, B., Weigelt, O., Hergert, J., Gurt, J., & Gelléri, P. (2017). The use of snowball sampling for multi source organizational research: Some cause for concern. Personnel Psychology, 70(3), 635-673. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12169 [ Links ]

Marion-Paris, E., Beetlestone, E., Paris, R., Bouhadfane, M., Villa, A., & Lehucher-Michel, M.P. (2023). Job retention for people with bipolar disorder: A qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 64(2), 171-178. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12876 [ Links ]

McIntyre, R.S., & O'Donovan, C. (2004). The human cost of not achieving full remission in depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(1), 10-16. [ Links ]

McRee, J. (2017). How perceptions of mental illness impact EAP utilization. Benefits Quarterly, 33(1), 37. [ Links ]

Montejano, L.B, Goetzel, R.Z. & Ozminkowski, R.J. (2005). The impact of bipolar disorder on employers. Disease Management & Health Outcomes, 13(4), 267-280. https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200513040-00005 [ Links ]

Morse, J., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2017). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100202 [ Links ]

Nahrgang, J.D., & Seo, J.J. (2015). How and why high leader-member exchange (LMX) relationships develop: Examining the antecedents of LMX. In T.N. Bauer & B. Erdogan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of leader-member exchange (pp. 87-118). Oxford Academic.

Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M.B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1304463 [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Verbeek, J.H., de Boer, A.G., Blonk, R.W., & Van Dijk, F.J. (2004). Supervisory behaviour as a predictor of return to work in employees absent from work due to mental health problems. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(10), 817-823. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2003.009688 [ Links ]

Onuh, J., Mbah, P., Ajaero, C., Orjiakor, C., Igboeli, E., & Ayogu, C. (2021). Rural-urban appraisal of the prevalence and factors of depression status in South Africa. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4, 100082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100082 [ Links ]

Parker, C., Scott, S., & Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball sampling. SAGE Research Methods Foundations.

Peterson, D., Gordon, S., & Neale, J. (2017). It can work: Open employment for people with experience of mental illness. Work, 56(3), 443-454. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-172510 [ Links ]

Porter, S., Lexén, A., & Bejerholm, U. (2019). Employers' beliefs, knowledge and strategies used in providing support to employees with mental health problems. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 51(3), 325-337. https://doi.org/10.3233/jvr-191049 [ Links ]

Posel, D., Oyenubi, A., & Kollamparambil, U. (2021). Job loss and mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown: Evidence from South Africa. PLoS One, 16(3), e0249352. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249352 [ Links ]

Pelham, B., & Boninger, D. (2020). Introductory psychology in modules. Taylor & Francis Group.

Pyc, L., Meltzer, D., & Liu, C. (2017). Ineffective leadership and employees' negative outcomes: The mediating effect of anxiety and depression. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(2), 196-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000030 [ Links ]

Rai, H. (2009). Gender differences: Ingratiation and leader member exchange quality. Singapore Management Review, 31(1), 63-73. [ Links ]

Ray, B., & Dollar, C. (2014). Exploring stigmatization and stigma management in mental health court: Assessing modified labeling theory in a new context. Sociological Forum, 29(3), 720-735. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12111 [ Links ]

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698-714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698 [ Links ]

Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C.D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 45(2), 209-213. [ Links ]

Sallis, A., & Birkin, R. (2013). Experiences of work and sickness absence in employees with depression: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(3), 469-483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-013-9481-6 [ Links ]

Sampath, P., Baral, R., & Rastogi, M. (2020), Crossover of work-family conflict in supervisor-subordinate dyads in India: Does LMX matter? South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 9(3), 373-390. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-11-2019-0212 [ Links ]

Schermuly, C.C., & Meyer, B. (2015). Good relationships at work: The effects of leader-member exchange and team-member exchange on psychological empowerment, emotional exhaustion, and depression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(5), 673-691. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2060 [ Links ]

Spitzer, R.L., & Wakefield, J.C. (1999). DSM-IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: Does it help solve the false positives problem? American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(12), 1856-1864. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.12.1856 [ Links ]

Stander, M.P., Bergh, M., Miller-Janson, H.E., De Beer, J.C., & Korb, F.A. (2016). Depression in the South African workplace. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 22(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v22i1.814 [ Links ]

Stein, D.J., Seedat, S., Herman, A., Moomal, H., Heeringa, S.G., Kessler, R.C., & Williams, D.R. (2008). Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in South Africa. British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(2), 112-117. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.029280 [ Links ]

Stevenson, D. (2017). Thriving at work: The Stevenson/Farmer review of mental health and employers. Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/thriving-at-work-a-review-of-mental-health-and-employers

Stuart, H. (2006). Mental illness and employment discrimination. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(5), 522-526. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002 [ Links ]

Suifan, T.S., Abdallah, A.B., & Al Janini, M. (2018). The impact of transformational leadership on employees' creativity. Management Research Review, 41(1), 113-132. https://doi.org/10.1108/mrr-02-2017-0032 [ Links ]

Summers, J., Howe, M., McElroy, J., Ronald Buckley, M., Pahng, P., & Cortes-Mejia, S. (2018). A typology of stigma within organizations: Access and treatment effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 853-868. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2279 [ Links ]

Taubman, D.S., & Parikh, S.V. (2023). Understanding and addressing mental health disorders: A workplace imperative. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(10), 455-463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-023-01443-7 [ Links ]

Tokumitsu, K., Yasui-Furukori, N., Adachi, N., Kubota, Y., Watanabe, Y., Miki, K., … & Yoshimura, R. (2023). Predictors of psychiatric hospitalization among outpatients with bipolar disorder in the real-world clinical setting. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1078045. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1078045 [ Links ]

Tomlinson, M., Grimsrud, A., Stein, D.J., Williams, D.R., & Myer, L. (2009). The epidemiology of major depression in South Africa: Results from the South African stress and health study. South African Medical Journal, 99(5), 368-373. Retrieved from http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/3102/2370 [ Links ]

Van Breukelen, W., Schyns, B., & Le Blanc, P. (2006). Leader-member exchange theory and research: Accomplishments and future challenges. Leadership, 2(3), 295-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715006066023 [ Links ]

Vooijs, M., Leensen, M.C., Hoving, J.L., Wind, H., & Frings-Dresen, M.H. (2017). Value of work for employees with a chronic disease. Occupational Medicine, 68(1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx178 [ Links ]

Wagner, C., Kawulich, B., & Garner, M. (2012). Doing social research: A global context. McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Wayne, S.J., Shore, L.M., & Liden, R.C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82-111. https://doi.org/10.2307/257021 [ Links ]

Welthagen, C., & Els, C. (2012). Depressed, not depressed or unsure: Prevalence and the relation to well-being across sectors in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 38(1), a984. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v38i1.984 [ Links ]

Westerman, C.Y.K., Currie-Mueller, J.L., Motto, J.S., & Curti, L.C. (2016). How supervisor relationships and protection rules affect employees' attempts to manage health information at work. Health Communication, 32(12), 1520-1528. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1234538 [ Links ]

Wiklund, J., Hatak, I., Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D.A. (2018). Mental disorders in the entrepreneurship context: When being different can be an advantage. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(2), 182-206. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0063 [ Links ]

Winkler, I. (2010). Leader-member exchange theory. In: Contemporary leadership theories. Contributions to management science (pp. 47-53), Physica-Verlag HD.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Sumari O'Neil

sumari.oneil@up.ac.za

Received: 26 Jan. 2023

Accepted: 21 Nov. 2023

Published: 20 Feb. 2024