Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Journal of Human Resource Management

On-line version ISSN 2071-078X

Print version ISSN 1683-7584

SAJHRM vol.21 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v21i0.2354

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The psychological contract and staff retention among South African higher education employees: The influence of socio-demographics

Annette Snyman; Nadia Ferreira

Department of Human Resource Management, College of Economic and Management Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: The global skills crisis, 'the great resignation', and technological advancements have impacted the higher education (HE) sector in South Africa. Staff retention is at risk because of the specialised skills sought by institutions, making employment relationships and skill retention top priorities

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The aim of this study was to explore the influence of socio-demographic differences on the relationship between psychological contract preferences and staff retention among South African HE employees

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: High staff turnover in South African HE sector and inability to retain crucial skilled employees pose challenges for HE institutions (HEIs) in a complex and diverse environment

RESEARCH APPROACH/DESIGN AND METHOD: A cross-sectional quantitative survey was conducted on a purposively selected population of full-time employees, both academic and administrative, with a final random sample of participants (N = 493) employed in an open-distance HEI in South Africa. Inferential statistics, specifically tests for significant mean differences, were performed

MAIN FINDINGS: Higher education employees from different race, gender, age, job level and tenure groups differ considerably in terms of their psychological contract preferences and their satisfaction with organisational retention practices

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Interventions for HE staff retention should prioritise strengthening diverse employees' psychological contracts, meeting their needs, and ensuring fulfilment of promises and commitments in the employment relationship

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: This paper's unique contribution lies in the new insight it provides into the psychological contract and retention-related preferences of diverse employees in the South African HE context

Keywords: higher education; open-distance learning; psychological contract; socio-demographics; staff retention; staff turnover.

Introduction

Key focus of the study

Higher education institutions (HEIs) in South Africa (SA) are experiencing immense challenges in retaining their skilled and valuable employees (Mukwawaya, 2022; Omodan, 2022; Takawira et al., 2014; Theron et al., 2014). Empirical evidence suggests that employees' satisfaction in terms of their psychological contracts has a significant influence on employee turnover and staff retention (Agarwal & Bhargava, 2013; Kumar & Santhosh, 2014). In SA, HEIs operate in a complex environment and have a diverse workforce in terms of socio-demographic groups (Mampane, 2019). However, there is limited research on the influence of socio-demographics pertaining to psychological contracts and retention of staff at HEIs. Thus, the present study investigates the influence of socio-demographic differences among higher education (HE) employees, in relation to psychological contract preferences and staff retention.

Background of the study

While research confirms the association between the psychological contract and staff retention, as well as the importance of psychological contract preferences in strengthening retention and lowering turnover (Deas, 2017; Kraak et al., 2017; Peirce et al., 2012; Snyman, 2021; Van der Vaart, et al., 2013; Van Stormbroek & Blomme, 2017), less attention has been given to the influence of socio-demographical differences on the relationship between these two concepts (Deas, 2017; Rafiee et al., 2015). Furthermore, there is a shortage of research on socio-demographic differences among employees in HEIs - especially in open-distance learning (ODL) institutions - in terms of how employees' psychological contracts impact staff retention (Deas, 2018; Peltokorpi et al., 2015; Rafiee et al., 2015). Based on the high staff turnover rates at HEIs in SA (Barkhuizen et al., 2020), as well as the diversity of the workforce at these institutions (Setati et al., 2019), it is imperative that these institutions develop and implement retention strategies aimed at strengthening the retention of their valuable and diverse employees. Therefore, the present study aims to address this gap by specifically exploring the socio-demographical differences among employees in HEIs, and the role these differences play in the relationship between their psychological contract-related perceptions and the retention of staff. The findings of the study can therefore potentially add valuable new insights that could inform retention practices for diverse employees employed in the HE environment.

Staff retention in the higher education context

Higher education institutions in SA face immense difficulties in terms of skilled human resources and retention of their valuable and skilled employees, which has a devastating effect on the successful functioning of these institutions (Abugre, 2018; Barkhuizen et al., 2020; Deas, 2018; Erasmus et al., 2015; Gerstein & Friedman, 2016; Mukwawaya, 2022; Musakuro, 2022; Robyn, 2012; Tettey, 2006). Previous research suggests that there may be as much as a 13% shortage of academic and support staff at HEIs (Abugre, 2018; Deas & Coetzee, 2020; Dewhurst et al., 2013). Research by Theron et al. (2014) determined that 33.8% of employees in South African HEIs showed a strong intention to leave their institutions. Higher Education of South Africa (HESA, 2011), Lindathaba-Nkadimene (2020), as well as Omodan (2022) likewise, concluded that HEIs are battling with poor levels of staff retention and high labour turnover.

If HEIs are not able to retain their key employees, they will not be able to remain competitive and offer quality services (Hailu et al., 2013). The high staff turnover in HEIs may be resulting from several challenges experienced in the HE sector, such as financial constraints, uncompetitive remuneration packages, mergers, acquisitions, job insecurity, lack of resources, and an overload of demands placed on employees (Balakrishnan & Vijayalakshmi, 2014; Ngobeni & Bezuidenhout, 2011; Robyn & Du Preez, 2013). Furthermore, South African HEIs operate in a multifaceted milieu with a socio-demographically diverse labour force.

In a South African study, Döckel (2003) identified six crucial retention factors (also referred to as retention practices) that organisations should consider when developing and implementing retention strategies (Döckel et al., 2006; Van Dyk & Coetzee, 2012). These factors comprise: compensation, job characteristics, opportunities for training and development, supervisor support, career opportunities, and work-life balance policies.

Thus, effective capacity building, and staff retention along with the type of relationship which progresses between diverse groups of employees and their employers, will ultimately determine the success of HEIs (Armstrong & Taylor, 2014; Festing & Schäfer, 2014; Guo, 2017; Mukwawaya, 2022; Snyman, 2022). Employees are one of the most important assets of any organisation, and in order to ensure the success and efficient functioning of these institutions, it is imperative for HEIs to develop and implement retention practices which take the needs of various socio-demographic groups into account. Higher education institutions can only diagnose and prevent turnover of their employees when there is a fruitful employment relationship and the diverse needs of their employees are appreciated and incorporated into retention practices (Grobler & Jansen van Rensburg, 2019; Ng'ethe et al., 2012).

The relationship between the psychological contract and staff retention

For HEIs to develop and implement retention strategies and practices aimed at addressing the high turnover levels, it is important to determine the factors that may have an impact on employees' decision to stay with or leave their organisation. Empirical evidence shows that the type of relationship that exists between employees and their employer, and the extent to which employees perceive their employer to adhere to commitments made within the relationship, strongly impact retention (Guest, 2004; Le Roux & Rothman, 2013; Van Stormbroek & Blomme, 2017). This may be referred to as the psychological contract between employees and employers (Bal & Kooij, 2011; Rousseau, 1989). The psychological contract is a subjective, unwritten, open-ended contract based on the reciprocal expectations of both parties to the employment relationship (Eds. Guest et al., 2010; Kraak et al., 2017; Rousseau, 1989; 1990; 1995).

The state of employees' psychological contracts is largely determined by the extent to which perceived promises made to them have been kept and obligations adhered to (Van der Vaart et al., 2013; Van Stormbroek & Blomme, 2017). The psychological contract is the basis of the employment relationship and has an enormous impact on employee retention (Guest, 1998; Kraak et al., 2017; Van der Vaart et al., 2015). When employees have a strong psychological contract with their employer, they are less likely to leave their organisation and more likely to be committed to their employer (Chin & Hung, 2013; Deas, 2017; Ngakantsi, 2022). Previous studies concur that perceived psychological contract breach negatively affects commitment and retention, and increases both planned and actual turnover (Deas, 2017; Peirce et al., 2012; Snyman, 2021; Van Dijk & Ramatswi, 2016).

A study by Deas (2017) showed that positive psychological contract-related perceptions are associated with higher satisfaction with the human resource factors that influence retention, namely, compensation, job characteristics, training and development opportunities, supervisor support, career opportunities, and work-life balance policies (Deas, 2017; Döckel; 2003; Döckel et al., 2006).

Socio-demographic differences

Several empirical studies have indicated that socio-demographic differences between diverse employees are among the most important factors to be considered when retention practices and strategies are developed and implemented by organisations (Peltokorpi et al., 2015; Potgieter & Mathonsi, 2021; Rafiee et al., 2015; Randmann, 2013). Socio-demographic variables such as race, gender, age, job level and tenure may also assist HEIs in predicting organisational commitment and strengthening retention (Rafiee et al., 2015; Randmann, 2013). Thus, considering the needs of diverse racial and age groups, and the predilections of different job levels, tenure groups and genders within an organisation can assist HEIs in the reinforcement of the retention of their skilled and valuable staff (Peltokorpi et al., 2015).

Various empirical studies, especially in the HE environment, have indicated that the extent to which employees value the retention practices offered by an organisation, for instance, their compensation packages, their work-life balance opportunities or their career development prospects, may be different among socio-demographic groups (Deas, 2017; Ng'ethe et al., 2012; Snyman et al., 2015). This implies that employees from dissimilar socio-demographic groups may not consider the same factors as equally important when deciding whether to stay or leave their organisation (Chin & Hung, 2013; Ryan et al., 2012).

In terms of employees' psychological contracts, research has correspondingly shown that diverse socio-demographic groups do necessarily not share the same expectations within their employment relationships (Kraak et al., 2017; Peltokorpi et al., 2015). Different socio-demographic groups may not have the same perceptions in terms of what is regarded as detrimental to the continuation of a fruitful employment relationship, and what would result in psychological contract fulfilment and/or breach (Blomme et al., 2010; Chin & Hung, 2013). In the HEIs specifically, studies concluded that employees' preferences related to their psychological contracts, that is, their perceptions of the necessary components for a healthy employment relationship with their employer, vary among different socio-demographic groups (Deas, 2017; Snyman, 2015).

The preceding discussion leads to the main research question related to the present study, namely, 'What is the influence of socio-demographic differences on the relationship between psychological contract preferences and staff retention among South African HE employees?'.

Research objective

This study aimed to extend the extant body of knowledge on the relationship between the psychological contract and staff retention of South African HE employees by their socio-demographic information. The present study aimed to explore: (1) the socio-demographical differences among employees in HEIs, in terms of their psychological contract preferences in relation to staff retention, and (2) the influence of socio-demographic differences on the relationship between psychological contract preferences and staff retention among South African HE employees. Exploring the relationship between the psychological contract and satisfaction with retention practices could aid in devising successful retention strategies, particularly for the varied and multicultural workforce in South African HEIs.

Research design

Research approach

A cross-sectional quantitative research approach was followed in order to achieve the aim of the study. Empirical data was collected using an electronic survey, from full-time employees in a single ODL HEI in SA. A cross-sectional research design is useful in the collection of large-scale data from a target population, and this design has the possibility to contain multiple variables at a single time (Spector, 2019).

Participants

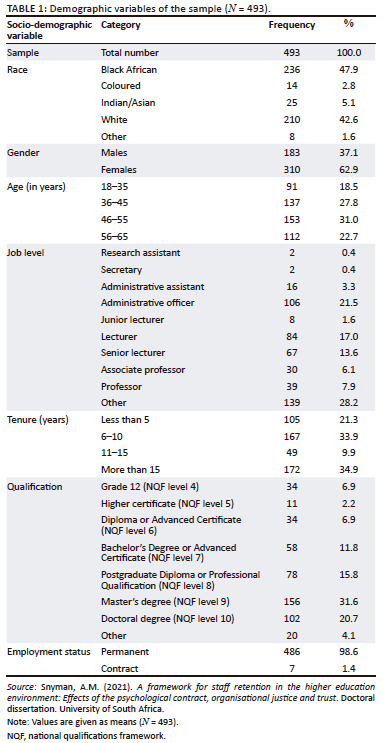

The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are outlined in Table 1.

The participants were employees (N = 493) of a South African (SA) ODL HEI. As specified in Table 1, the sample comprised mainly black (48%), permanently employed (99%) females (63%), and aged between 26 years and 35 years. Table 1 also shows that most of the participants (22%) were employed as administrative officers or senior lecturers (14%). Furthermore, most of the participants (35%) had worked for the institution for longer than 15 years or between 6 years and 10 years (34%), and had a Master's degree (32%) or a Doctorate degree (21%).

Measuring instruments

Participants completed the Psycones Questionnaire (PQ) (Guest et al., 2010; Psycones, 2006) and the Retention Factor Measurement Scale (RFMS) (Döckel, 2003; Döckel et al., 2006). Participants also self-reported their socio-demographic information, including their race, gender, age, job level, and tenure.

Psychological contract

Participants' psychological contract preferences were measured using the PQ (Guest et al., 2010; Psycones, 2006), developed by the Psycones project (Psycones, 2006). The PQ consists of 43 items and 4 subscales (employer obligations, employee obligations, state of the psychological contract and job satisfaction), and items are scored on a five-point Likert-type scale where 1 is 'strongly disagree', and 5 is 'strongly agree'.

The employer obligations subscale relates to a person's perception of promises made by the organisation and encompasses questions like: 'Has your organisation promised or committed itself to providing you with a job that is challenging?' and 'Has your organisation promised or committed itself to allowing you to participate in decision-making?'. The employee obligations subscale pertains to an individual's perception of his or her promises made to the organisation and entails questions such as: 'Have you promised or committed yourself to showing loyalty to your organisation?' and 'Have you promised or committed yourself to being a good team player?'. The job satisfaction subscale includes six statements to establish participants' emotional feelings related to the psychological contract, for example, statements such as: 'I feel happy', 'I feel sad', 'I feel pleased'. Lastly, the fourth subscale concerns the overall state of the psychological contract and contains statements like: 'Do you feel that organisational changes are implemented fairly in your organisation?' and 'Do you feel fairly treated by managers and supervisors?'.

The Cronbach's alpha coefficients for scores from the PQ range from 0.70 to 0.95 (Psycones, 2006). In the current study, the reliability of scores from the PQ was 0.94 for employer obligations, 0.90 for employee obligations, 0.90 for job satisfaction, and 0.87 for the overall state of the psychological contract.

Employee retention satisfaction

The RFMS comprises 35 items and 6 subscales (compensation, job characteristics, training and development opportunities, supervisor support, career opportunities and work/life balance) and are scored on a six-point Likert-type scale, where participants had to indicate how satisfied or dissatisfied they feel about their organisation regarding certain statements. The scale ranges from 1 being 'strongly disagree' to 5 being 'strongly agree'.

The first subscale measures participants' opinions about the importance of compensation and includes statements regarding, for example: 'My benefits package' and 'My most recent raise'. In the second subscale, participants' views about the importance of job satisfaction are determined and comprises statements, for instance: 'The job requires me to use a number of complex or high-level skills' and 'The job is quite simple and repetitive'. The third subscale relates to training and measures participants' perceptions of the importance of training, including for example: 'This company provides me with job-specific training' and 'Sufficient time is allocated for training'.

The fourth subscale relates to participants' views regarding their supervisor support, and includes statements such as: 'I feel undervalued by my supervisor' and 'My supervisor seldom recognises an employee for work well done'. The fifth subscale measures participants' perceptions regarding their career opportunities, for example: 'My chances for being promoted are good' and 'It would be easy to find a job in another department'. In the sixth and final subscale, participants' views on work/life balance were assessed, with statements such as: 'I often feel like there is too much work to do' and 'My work schedule is often in conflict with my personal life'.

Previous empirical research reported internal consistency reliabilities of 0.80 to 0.90 for scores from the RFMS (Döckel, 2003). In the present study, the reliability of scores from the RFMS was 0.94 for compensation, 0.64 for job characteristics, 0.90 for training and development opportunities, 0.85 for supervisor support, 0.80 for career opportunities, and 0.89 for work-life balance.

Research procedure

In all, 4 882 questionnaires were distributed, with a total of 493 usable questionnaires returned (N = 493), yielding a response rate of 10.1%. The participants were invited to voluntarily participate in the study. The questionnaires were distributed electronically through an e-mail link. Each questionnaire encompassed a cover letter inviting respondents to participate voluntarily in the research study and guaranteeing them the anonymity and confidentiality of their individual responses. The cover letter also stated that by completing the questionnaires constituted informed consent and agreement for the results to be used for research purposes only.

Statistical analysis

The first stage of the data analysis process involved determining the means, standard deviations and Cronbach's alpha coefficients. In the second stage, to test the strength and direction of the relationship between the PQ and RFMS variables, Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient (r) was applied. Also, to determine the relationship between the socio-demographic variables (race, gender, age, job level and tenure), and the PQ and RFMS variables, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (p) was employed. The practical significance of correlation coefficients was determined using the following cut-off points: r ≥ 0.30 (medium effect) and p ≤ 0.05 (Humphreys et al., 2019; Liu, 2019).

The third stage of the data analysis involved testing for significant differences in psychological contract-related preferences and satisfaction with retention factors, by the socio-demographic factors (race, gender, age, job level and tenure). The Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Cramer-von Mises and Anderson-Darling tests showed that the data were normally distributed, and thus, parametric tests were applied. In order to measure the differences between the socio-demographic variables of race, gender, age, job level and tenure, ANOVAs (analysis of variance) and post-hoc tests were conducted. Also, to assess the differences between the genders, a t-test and Tukey's studentised range tests were used (Lee & Lee, 2018). Finally, Cohen's d test was utilised to establish the practical effect size regarding the differences between the relevant groups (Cohen & Cohen, 2014; Cohen et al., 2013).

Results

Descriptive statistics and construct validity and reliability statistics

The descriptive statistics and the construct validity and reliability statistics for the study variables are presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, Cronbach's alpha coefficients and composite reliability (CR) values were all above > 0.85, which displays high internal consistency reliability of the PQ. Table 2 also indicates the convergent validity of the PQ, with the CR values being more significant than the average variance extracted (AVE) values and the AVE values of employer obligations (0.50) and job satisfaction (0.58) being ≥ 0.50, which is acceptable. The AVE values of employee obligations (0.41) and the state of the psychological contract (0.46) were just below the threshold of ≥ 0.50.

Furthermore, Table 2 specifies that the Cronbach alpha coefficients and CR values were above > 0.70 (except for the job characteristics subscale), indicating good internal consistency reliability of the RFMS. The reliability coefficients for the job characteristics subscale (α = 0.64; CR = 0.60) were acceptable for large-group analysis purposes. However, the lower reliability of the subscale was considered in the interpretation of the findings. The convergent validity of the RFMS with the CR values being larger than the AVE values, and the AVE values of compensation (0.56), training and development opportunities (0.61) and work-life balance (0.70) being ≥ 0.50, is acceptable.

Bivariate correlation analysis

Table 3 summarises the results of the correlations between the psychological contract (PQ) and retention factors (RFMS).

As shown in Table 3, the relations were all significant and positive, ranging between r ≥ 0.15 ≤ 0.90 (small to sizeable practical effect size; p ≤ 0.05). The four subscale dimensions of the PQ also had significant and positive correlations with the overall RFMS (r ≥ 0.45 ≤ 0.67; large practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001) signifying the construct validity of the general construct of the psychological contract.

In addition, as indicated in Table 3, the results showed a significant correlation between the six subscale dimensions of the RFMS, in the range of r ≥ 0.14 ≤ 0.48 (small to sizeable practical effect size; p ≤ 0.05). The six subscale dimensions of the RFMS also had significant and positive correlations with the overall PQ scale (r ≥ 0.64 ≤ 0.73; large practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001), indicating the construct validity of the general construct of satisfaction with human resource retention factors.

Table 4 summarises the results of the correlations between the socio-demographic variables, the psychological contract (PQ), and retention factors (RFMS).

As specified in Table 4, the results displayed a significant negative bivariate correlation between race and employee obligations (PQ scale) (r = -0.14; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001); job satisfaction (PQ scale) (r = -0.17; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001); and state of the psychological contract (PQ scale) (r = -0.16; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001). The results further showed a significant negative bivariate correlation with the overall PQ (r = -0.11; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.01) career opportunities (RFMS) (r = -0.27; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001).

In terms of gender, Table 4 shows no significant bivariate correlations between gender and any of the subscales and overall scales of the PQ and RFMS. In terms of age, Table 4 indicates no significant bivariate correlations between age and any of the subscales and overall scales of the PQ and RFMS. Furthermore, the results showed a significant positive bivariate correlation between job level and job characteristics (RFMS) (r = 0.20; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001); supervisor support (RFMS) (r = 0.11; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.01); work-life balance (RFMS) (r = 0.15; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001); and employer obligations (PQ scale) (r = 0.09; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.05).

Lastly, the results showed a significant negative bivariate correlation between tenure and job satisfaction (PQ scale) (r = -0.17; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001). A significant negative bivariate correlation was found between career opportunities (r = -0.30; moderate practical effect size; p ≤ 0.001) and the overall RFMS (r = -0.11; small practical effect size; p ≤ 0.01).

Tests for significant differences between socio-demographic groups

The results from the tests for significant differences between the socio-demographic groups in terms of their psychological contract-related preferences, as well as their satisfaction with retention factors, are outlined and discussed below.

Race

Table 5 provides a summary of the ANOVAs and post hoc tests investigating the relationship between the socio-demographic variable of race and the psychological contract-related variables (PQ) and the satisfaction with retention-related variables (RFMS). Overall PQ, job satisfaction, and state of the psychological contract (PQ scale), as well as overall RFMS, supervisor support, career opportunities and work-life balance (RFMS) showed significant mean differences.

With regard to the psychological contract-related variables, Indians and/or Asians scored significantly higher than white people on overall PQ (Indians and/or Asians: mean (M) = 4.45; standard deviation (SD) = 0.65; white people: M = 3.99; SD = 0.65; d = 0.71; moderate practical effect) as well as state of the psychological contract (Indians and/or Asians: M = 3.36; SD = 0.95; white people: M = 2.83; SD = 0.84; d = 0.59; moderate practical effect). Furthermore, black Africans scored significantly higher than white people in terms of job satisfaction (black African: M = 4.22; SD = 0.96; white people: M = 3.87; SD = 0.93; d = 0.37; small practical effect) as well as state of the psychological contract (black African: M = 3.11; SD = 0.90; white people: M = 2.83; SD = 0.84; d = 0.32; small practical effect).

In terms of the satisfaction with retention practices-related variables, Indians and/or Asians scored significantly higher than white people for overall RFMS (Indians and/or Asians: M = 4.08; SD = 0.84; white people: M = 3.63; SD = 0.68; d = 0.59; moderate practical effect), supervisor support (Indians and/or Asians: M = 4.66; SD = 1.21; white people: M = 3.86; SD = 1.39; d = 0.61; moderate practical effect), as well as career opportunities (Indians and/or Asians: M = 3.59; SD = 1.20; white people: M = 2.76; SD = 1.07; d = 0.73; moderate practical effect). In addition, black Africans scored significantly higher than white people in terms of overall RFMS (black African: M = 3.82; SD = 0.72; white people: M = 3.63; SD = 0.68; d = 0.27; small practical effect), career opportunities (black African: M = 3.48; SD = 1.35; white people: M = 2.76; SD = 1.07; d = 0.59; moderate practical effect), and work-life balance (black African: M = 3.94; SD = 1.45; white people: M = 2.73; SD = 1.40; d = 0.85; large practical effect). Black people also scored significantly higher than other racial groups in terms of work-life balance (black African: M = 3.94; SD = 1.45; other: M = 2.28; SD = 1.48; d = 1.13; large practical effect).

Gender

The results of the t-test and mean scores investigating the relationship between the socio-demographic variable of gender and the psychological contract-related variables (PQ) and the satisfaction with retention-related variables (RFMS) are reported in Table 6.

Table 6 indicates the results of the t-test procedure. Significant mean differences were obtained between males and females for work-life balance (males: M = 3.54; SD = 1.54; females: M = 3.24; SD = 1.54; t = 2.13; d = 0.19; small practical effect) in terms of the satisfaction with the retention practices-related variable work-life balance.

Age

Table 7 provides a summary of the ANOVAs and post hoc tests investigating the relationship between the socio-demographic variable of age and the psychological contract-related variables (PQ) and the satisfaction with retention-related variables (RFMS). As indicated in Table 7, significant mean differences were only observed for the RFMS subscales of job characteristics, career opportunities and work-life balance with regard to age.

In terms of the satisfaction with retention practices-related variables, job characteristics showed significant mean differences between the 46 years to 55 years and 18 years to 35 years age groups (46 years to 55 years: M = 4.55; SD = 1.08; 18 years to 35 years: M = 4.06; SD = 0.94; d = 0.48; small practical effect) as well as the 56 years to 65 years and 18 years to 35 years age groups (56 years to 65 years: M = 4.50; SD = 1.08; 18 years to 35 years: M = 4.06; SD = 0.94; d = 0.48; small practical effect). In the case of career opportunities, significant mean differences were observed between the age groups of 18 years to 35 years and 56 years to 65 years (18 years to 35 years: M = 3.40; SD = 1.21; 56 years to 65 years: M = 2.81; SD = 1.07; d = 0.52; moderate practical effect), as well as between 46 years to 55 years and 56 years to 65 years (46 years to 55 years: M = 3.22; SD = 1.37; 56 years to 65 years: M = 2.81; SD = 1.07; d = 0.33; small practical effect). Lastly, in terms of work-life balance, significant mean differences were found between the age groups of 36 years to 45 years and 46 years to 55 years (36 years to 45 years: M = 3.73; SD = 1.56; 46 years to 55 years: M = 3.17; SD = 1.54; d = 0.36; small practical effect), 36 years to 45 years and 56 years to 65 years (36 years to 45 years: M = 3.73; SD = 1.56; 56 years to 65 years: M = 2.86; SD = 1.41; d = 0.59; moderate practical effect), 18 years to 35 years and 46 years to 55 years (18 years to 35 years: M = 3.70; SD = 1.50; 46 years to 55 years: M = 3.17; SD = 1.54; d = 0.35; small practical effect), as well as between 18 years to 35 years and 56 years to 65 years (18 years to 35 years: M = 3.70; SD = 1.50; 56 years to 65 years: M = 2.86; SD = 1.41; d = 0.58; moderate practical effect).

Job level

The results of the ANOVAs and post hoc tests examining the relationship between the psychological contract-related variables (PQ), the organisational justice-related variables (OJM), the trust-related variables (TRA) and the satisfaction with retention-related variables (RFMS) and the socio-demographic variable of job level are provided in Table 8. Significant mean differences were only observed in terms of employer obligations (PQ scale), job characteristics, training and development opportunities and work-life balance (RFMS) and are reported in Table 8.

With regard to the psychological contract-related variables, employer obligations showed significant mean differences between the job level of professor and the 'other' grouping (professor: M = 3.95; SD = 0.98; other: M = 3.51; SD = 1.44; d = 0.36; small practical effect), professor and administrative officer job level (professor: M = 3.95; SD = 0.98; administrative officer: M = 3.19; SD = 1.25; d = 0.68; moderate practical effect), as well as professor and the job level of administrative assistant (professor: M = 3.95; SD = 0.98; administrative assistant: M = 3.54; SD = 1.38; d = 0.34; small practical effect). Furthermore, significant mean differences were observed between the job levels of associate professor and administrative officer (associate professor: M = 3.78; SD = 1.25; administrative officer: M = 3.19; SD = 1.25; d = 0.47; small practical effect), lecturer and administrative officer (lecturer: M = 3.82; SD = 1.17; administrative officer: M = 3.19; SD = 1.25; d = 0.52; moderate practical effect), including between senior lecturer and administrative officer (senior lecturer: M = 3.65; SD = 0.96; administrative officer: M = 3.19; SD = 1.25; d = 0.41; small practical effect).

In terms of the satisfaction with retention practices-related variables, significant mean differences were found between the job levels of professor and administrative officer for job characteristics (professor: M = 5.04; SD = 0.97; administrative officer: M = 3.90; SD = 1.06; d = 1.12; large practical effect), training and development opportunities (professor: M = 4.41; SD = 1.08; administrative officer: M = 3.42; SD = 1.27; d = 0.84; large practical effect), and work-life balance (professor: M = 2.44; SD = 1.25; administrative officer: M = 4.03; SD = 1.49; d = 1.16; large practical effect). Also, significant mean differences were found between the job levels of professor and administrative assistant for job characteristics (professor: M = 5.04; SD = 0.97; administrative assistant: M = 3.86; SD = 0.89; d = 1.27; large practical effect) and work-life balance (professor: M = 2.44; SD = 1.25; administrative assistant: M = 4.06; SD = 1.56; d = 1.15; large practical effect).

Also with regard to the satisfaction with retention practices-related variables, significant mean differences were observed between the job level of lecturer and various job levels, including administrative officer (lecturer: M = 4.65; SD = 0.87; administrative officer: M = 3.90; SD = 1.06; d = 0.77; moderate practical effect) for job characteristics; 'other' job levels (lecturer: M = 4.32; SD = 1.26; other: M = 3.75; SD = 1.40; d = 0.43; small practical effect) and administrative officer (lecturer: M = 4.32; SD = 1.26; administrative officer: M = 3.42; SD = 1.27; d = 0.71; moderate practical effect) for training and development opportunities; as well as administrative officer for work-life balance (lecturer: M = 3.10; SD = 1.45; administrative officer: M = 4.03; SD = 1.49; d = 0.63; moderate practical effect). The job level of administrative officer likewise showed significant mean differences with numerous job levels, excluding the ones already mentioned, including associate professor (administrative officer: M = 3.90; SD = 1.06; associate professor: M = 4.68; SD = 1.04; d = 0.74; moderate practical effect), senior lecturer (administrative officer: M = 3.90; SD = 1.06; senior lecturer: M = 4.48; SD = 0.93; d = 0.58; moderate practical effect) and 'other' job levels (administrative officer: M = 3.90; SD = 1.06; other: M = 4.45; SD = 1.06; d = 0.52; moderate practical effect) for job characteristics; as well as senior lecturer (administrative officer: M = 4.03; SD = 1.49; senior lecturer: M = 2.82; SD = 1.34; d = 0.85; large practical effect), associate professor (administrative officer: M = 4.03; SD = 1.49; associate professor: M = 2.73; SD = 1.51; d = 0.87; large practical effect), and 'other' job levels (administrative officer: M = 4.03; SD = 1.49; other: M = 3.48; SD = 1.55; d = 0.74; moderate practical effect) for work-life balance.

Tenure

Table 9 provides a summary of ANOVAs and post hoc tests investigating the relationship between the psychological contract-related variables (PQ), the OJM, the TRA and the satisfaction with retention-related variables (RFMS) and the socio-demographic variable of tenure. Overall RFMS, training and development opportunities, career opportunities and work-life balance (RFMS), as well as overall PQ and job satisfaction (PQ scale), showed significant mean differences and are reported in Table 9.

In terms of the psychological contract-related variables, significant mean differences were found between the groups tenured less than 5 years and more than 15 years for overall PQ (less than 5 years: M = 4.26; SD = 0.68; more than 15 years: M = 4.02; SD = 0.73; d = 0.34; small practical effect), and job satisfaction (less than 5 years: M = 4.33; SD = 0.91; more than 15 years: M = 3.89; SD = 0.96; d = 0.47; small practical effect). Likewise with regard to the satisfaction with retention-related variables, significant mean differences were also found between the groups tenured less than 5 years and more than 15 years for overall RFMS (less than 5 years: M = 3.85; SD = 0.70; more than 15 years: M = 3.67; SD = 0.74; d = 0.38; small practical effect), training and development opportunities (less than 5 years: M = 4.26; SD = 1.21; more than 15 years: M = 4.0; SD = 1.29; d = 0.41; small practical effect), career opportunities (less than 5 years: M = 3.74; SD = 1.18; more than 15 years: M = 2.73; SD = 1.14; d = 0.87; large practical effect) as well as work-life balance (less than 5 years: M = 3.57; SD = 1.56; more than 15 years: M = 3.03; SD = 1.53; d = 0.35; small practical effect).

Furthermore, with the satisfaction with retention-related variables, significant mean differences were observed between the groups tenured less than 5 years and 6 years to 10 years for overall RFMS (less than 5 years: M = 3.95; SD = 0.70; 6 years to 10 years: M = 3.66; SD = 0.71; d = 0.41; small practical effect) and career opportunities (less than 5 years: M = 3.74; SD = 1.18; 6 years to 10 years: M = 3.27; SD = 1.29; d = 0.38; small practical effect). Additionally, significant mean differences were found between the groups tenured 6 years to 10 years and more than 15 years for career opportunities (6 years to 10 years: M = 3.27; SD = 1.29; more than 15 years: M = 2.73; SD = 1.14; d = 0.54; moderate practical effect) and work-life balance (6 years to 10 years: M = 3.60; SD = 1.48; more than 15 years: M = 3.03; SD = 1.53; d = 0.38; small practical effect). For career opportunities, significant mean differences were also found between the tenure groups of less than 5 years and 11 years to 15 years (less than 5 years: M = 3.74; SD = 1.18; 11 years to 15 years: M = 3.07; SD = 1.22; d = 0.56; moderate practical effect).

Discussion

The research presented in this article investigated the differences among socio-demographic groups, in relation to their psychological contract-related preferences, as well as their satisfaction with retention practices. The findings exhibited that individuals from different races, gender, age, job level and tenure groups differ substantially in terms of their psychological-related predispositions and their satisfaction with organisational retention practices. Specifically, employees from different races, tenure and job level groups, differ significantly regarding their overall psychological contract preferences, their perceptions of employer obligations, job satisfaction and the level of fulfilment of their psychological contracts. Also, individuals from diverse races, ages, tenure and job level groups vary regarding their overall contentment with retention practices, as well as their perceptions of their job characteristics, training and development opportunities, supervisor support and career opportunities and their work-life balance predispositions.

According to the study's results, certain groups of employees demonstrated the need for addressing their psychological contracts, indicating a lack of psychological contract fulfilment, including those from the white and coloured ethnic groups, administrative employees (administrative officers, administrative assistants and secretarial job levels), older employees (56 years to 65 years) and those who had worked for the institution for longer than 15 years. The results were confirmed by previous studies conducted by Barkhuizen and Rothmann (2008); Bellou (2009); Deas (2017); Ehlers and Jordaan (2016); Gurmessa et al. (2018) and Hofhuis et al. (2014). To maintain a fruitful employer-employee relationship, the institution should ensure that promises and commitments to all employees, especially these groups, are met and held. These groups conveyed apprehensions about training and development opportunities, career prospects, and support from supervisors. Thorough onboarding and orientation, clearly contracted personal development plans, fairness in performance management and appraisal, open discussions, mentoring support, transparency, joint decision-making, and relevant training and development opportunities for these groups may aid psychological fulfilment, which in turn, may enhance satisfaction with retention practices.

In addition, the results indicated that employees of white ethnicity, women, academic employees (professors, associate professors, senior lecturers and lecturers), older employees (56 years to 65 years) and employees with a tenure longer than 15 years require appropriate work-life balance opportunities. The results were confirmed by previous studies done by Deas (2017), Ip et al. (2020), and Oosthuizen et al. (2016). In the HE environment, the 56 years to 65 years age group is regarded as knowledge workers with experience, and they remain imperative for retention purposes because of the institution's need for mentoring and knowledge transfer to younger age groups (Bhatnagar, 2014; Gandy et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2016). The 56 years to 65 years age group, along with employees on a professor level and women, seem to have a stronger need than younger age groups and men, for clearly contracted work-life balance policies and supervisor support. Psychological contract interventions for these groups may include continuing education opportunities, participation in professional organisations and professional development opportunities, as well as work-life balance opportunities, such as working remotely and flexitime. In addition, enhancing supervisor support could be achieved through various means such as fostering transparent dialogues, implementing mentorship programmes, demonstrating honesty in establishing performance objectives, and encouraging supervisors to prioritise productivity over working hours.

In conclusion, HEIs should keep the needs of different socio-demographic groups in mind when developing and implementing retention strategies. Interventions aimed at increasing staff retention in the HE environment should focus on strengthening diverse employees' psychological contracts and ensuring that needs are met and promises and commitments are adhered to within the employment relationship. This may result in enhanced satisfaction with the organisation's retention practices and lower turnover.

Implications for theory and practice

This research has provided evidence that the psychological contract-related preferences and perceptions of HE employees differ among various socio-demographic groups. The study has also highlighted the crucial role played by employees' psychological contracts in influencing their satisfaction with their organisation's retention practices and their decision to stay or leave. Although previous research has established a connection between psychological contract fulfilment and staff retention, this paper's unique contribution is its novel perspective on the psychological contract and retention-related predispositions of the diverse workforce in the South African HE sector. Hence, the variations in socio-demographic factors among HE employees regarding their psychological contract preferences in relation to staff retention should inform the customisation of retention interventions and strategies in HEIs.

The findings of this study add to the existing body of knowledge on human resource management and staff retention strategies in the South African HE context. Understanding how socio-demographic factors influence employees' psychological contract fulfilment and satisfaction with organisational retention practices, can assist HEIs in retaining their diverse and valuable workforce.

Limitations of the study

The present study's sample comprised predominantly permanently employed, married, black African and white females, between the ages of 46 years and 55 years, in a single ODL, HEI. Thus, the research findings are not generalisable to employees of other sociodemographic groups or different industries. Furthermore, the participants in the sample were randomly sampled and consisted of only 493 participants; therefore, the sample was not big enough to adequately embody the entire population. Finally, the study did not assess the bi-directionality of the employment relationship, as only the views and perceptions of employees were considered. Subsequent studies should consider the viewpoints of both employees and employers, pertaining to the psychological contract and retention. Additionally, it is important to replicate the results of this study in the wider South African HE landscape.

Conclusion

Employee retention in the South African HE context remains a pressing matter which requires inquiry, because of the high turnover rates in this sector. The findings of the study offer new insights into the differences between HE employees from various socio-demographic groups, in terms of their psychological contract-related preferences and their satisfaction with retention practices. Acquiring an understanding of how socio-demographic characteristics influence employees' satisfaction with organisational retention practices and fulfilment of the psychological contract could aid HEIs in retaining their diverse and valuable workforce.

Acknowledgements

This article is partially based on the first author's thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Sciences at the University of South Africa, South Africa, with supervisors Prof. Melinde Coetzee and Prof. N.F., received in May 2021, available here: https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/27910/thesis_snyman_am.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The authors acknowledge Prof. Melinde Coetzee for her valuable input to this research.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

A.S and N.F. contributed to the conceptual framework, data collection and analysis, and writing up of the research article.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance to conduct the research was obtained from the University of South Africa (ERC Ref#: 2016_RPSC_076). Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that their participation was anonymous, confidential and private. Informed consent was also obtained in order to use the data for research purposes. Approved: 15 November 2016.

Funding information

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and are the product of professional research. It does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institution, funder, agency, or that of the publisher. The authors are responsible for this article's results, findings, and content.

References

Abugre, J.B. (2018). Institutional governance and management systems in Sub-Saharan Africa higher education: Developments and challenges in a Ghanaian Research University. Higher Education, 75(2), 323-339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0141-1 [ Links ]

Agarwal, A., & Bhargava, S. (2013). Effects of psychological contract breach on organizational outcomes: Moderating role of tenure and educational levels. The Journal for Decision Makers VIKALPA, 38(1), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090920130102 [ Links ]

Armstrong, M., & Taylor, S. (2014). Armstrong's handbook of human resource management practice (13th ed.). Kogan Page.

Bal, P.M., & Kooij, D. (2011). The relations between work centrality, psychological contracts, and job attitudes: The influence of age. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(4), 497-523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594321003669079 [ Links ]

Balakrishnan, L., & Vijayalakshmi, M. (2014). A study on retention strategies followed by education institutions in retaining qualified employees. SIES Journal of Management, 10(1), 69-78. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, N., & Rothmann, S. (2008). Occupational stress of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2), 321-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630803800205 [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, N., Lesenyeho, D., & Schutte, N. (2020). Talent retention of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 12(1), 191-207. [ Links ]

Bellou, V. (2009). Profiling the desirable psychological contract for different groups of employees: Evidence from Greece. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(4), 810-830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190902770711 [ Links ]

Bhatnagar, J. (2014). Mediator analysis in the management of innovation in Indian knowledge workers: The role of perceived supervisor support, psychological contract, reward and recognition and turnover intention. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(10), 1395-1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.870312 [ Links ]

Blomme, R.J., van Rheede, A., & Tromp, D.M. (2010). The use of the psychological contract to explain turnover intentions in the hospitality industry: a research study on the impact of gender on the turnover intentions of highly educated employees. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(1), 144-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190903466954 [ Links ]

Chin, P., & Hung, M. (2013). Psychological contract breach and turnover intention: The moderating roles of adversity quotient and gender. Social Behavior and Personality, 41(5), 843-860. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.5.843 [ Links ]

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (2014). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S.G., & Aiken, L.S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Deas, A.J. (2018). Managing diversity in talent retention: Implications of psychological contract, career preoccupations and retention factors. In: Coetzee, M., Potgieter, I., Ferreira, N. (eds), Psychology of Retention (pp. 331-351). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98920-4_16

Deas, A.J. (2017). Constructing a psychological retention profile for diverse generational groups in the higher educational environment. Doctoral dissertation. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Deas, A.J., & Coetzee, M. (2020). Psychological contract, career concerns, and retention practices satisfaction of employees: Exploring interaction effects. Current Psychology, 39, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00660-0 [ Links ]

Dewhurst, M., Hancock, B., & Ellsworth, D. (2013). Redesigning knowledge work. Harvard Business Review, 91(1), 58-64. [ Links ]

Döckel, A. (2003). The effect of retention factors on organisational commitment: an investigation of high technology employees. Masters dissertation. University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Döckel, A., Basson, J.S., & Coetzee, M. (2006). The effect of retention factors on organisational commitment: an investigation of high technology employees. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 4(2), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v4i2.91 [ Links ]

Ehlers, L., & Jordaan, C. (2016). A measure for employment relationship quality in South African supervisory relationships. Journal of Management & Administration, 2016(1), 1-35. [ Links ]

Erasmus, B.J., Grobler, A., & Van Niekerk, M. (2015). Employee retention in a higher education institution: An organisational development perspective. Progressio, 37(2), 33-63. https://doi.org/10.25159/0256-8853/600 [ Links ]

Festing, M., & Schäfer, L. (2014). Generational challenges to talent management: A framework for talent retention based on the psychological-contract perspective. Journal of World Business, 49(2), 262-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.010 [ Links ]

Gandy, R., Harrison, P., & Gold, J. (2018). Talent management in higher education: Is turnover relevant?. European Journal of Training and Development, 42(9), 597-610. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-11-2017-0099 [ Links ]

Gerstein, M., & Friedman, H.H. (2016). Rethinking higher education: Focusing on skills and competencies. Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management, 4(2), 104-121. https://doi.org/10.22381/PIHRM4220165 [ Links ]

Grobler, A., & Jansen van Rensburg, M. (2019) Organisational climate, person-organisation fit and turn over intention: A generational perspective within a South African Higher Education Institution. Studies in Higher Education, 44(11), 2053-2065. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1492533 [ Links ]

Guest, D.E. (1998). Is the psychological contract worth taking seriously? Journal of Organisational Behavior, 19(1), 649-664. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(1998)19:1+<649::AID-JOB970>3.0.CO;2-T [ Links ]

Guest, D.E. (2004). The psychology of the employment relationship: An analysis based on the psychological contract. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(4), 541-555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00187.x [ Links ]

Guest, D., Isaksson, K., & De Witte, H. (Eds.). (2010). Employment contracts and psychological contracts among European workers. Oxford University Press.

Guo, Y. (2017). Effect of psychological contract breach on employee voice behaviour: Evidence from China. Social Behavior and Personality, 45(6), 1019-1028. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6326 [ Links ]

Gurmessa, Z.B., Ferreira, I.W., & Wissink, H.F. (2018). Demographic factors as a catalyst for the retention of academic staff: A case study of three universities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 10(3 (J)), 169-186. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v10i3.2326 [ Links ]

Hailu, A., Mariam, D.H., Fekade, D., Derbew, M., & Mekasha, A. (2013). Turn-over of academic faculty at the College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University: A 20-year analysis (1991 to 2011). Human Resources for Health, 11(61), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-61 [ Links ]

Higher Education of South Africa (HESA). (2011). A generation of growth: Proposal for a national programme to develop the next generation of academics for South African higher education. University of South Africa.

Hofhuis, J., Van der Zee, K.I., & Otten, S. (2014). Comparing antecedents of voluntary job turnover among majority and minority employees. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 33(8), 735-749. https://doi.org/10.1108/edi-09-2013-0071 [ Links ]

Humphreys, R.K., Puth, M.T., Neuhäuser, M., & Ruxton, G.D. (2019). Underestimation of Pearson's product moment correlation statistic. Oecologia, 189(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-018-4233-0 [ Links ]

Ip, E.J., Lindfelt, T.A., Tran, A.L., Do, A.P., & Barnett, M.J. (2020). Differences in career satisfaction, work-life balance, and stress by gender in a national survey of pharmacy faculty. Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 33(4), 415-419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190018815042 [ Links ]

Kraak, J.M., Lunardo, R., Herrbach, O., & Durrieu, F. (2017). Promises to employees matter, self-identity too: Effects of psychological contract breach and older worker identity on violation and turnover intentions. Journal of Business Research, 70, 108-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.015 [ Links ]

Kumar, G.S., & Santhosh, C. (2014). Factor analysis approach to explore dimensions of employee retention in BPO industry in Kerala. Journal of Social Welfare and Management, 6(2), 69-78. [ Links ]

Lee, J., Chiang, F.F.T., Van Esch, E., & Cai, Z. (2016). Why and when organizational culture fosters affective commitment among knowledge workers: The mediating role of perceived psychological contract fulfilment and moderating role of organizational tenure. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(6), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1194870 [ Links ]

Lee, S., & Lee, D.K. (2018). What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test?. Korean Journal of Anaesthesiology, 71(5), 353. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.d.18.00242 [ Links ]

Le Roux, C.H., & Rothmann, S. (2013). Contractual relations between employers and employees in HEI: Individual and organisational outcomes. South African Journal of Higher Education, 27(4), 252-274. https://doi.org/10.20853/27-4-276 [ Links ]

Lindathaba-Nkadimene, K. (2020). The influence of working conditions on turnover among younger academics in a rural South African University. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 26(2), 1-13. [ Links ]

Liu, X.S. (2019). A probabilistic explanation of Pearson's correlation. Teaching Statistics, 41(3), 115-117. https://doi.org/10.1111/test.12204 [ Links ]

Mampane, S.T. (2019). Managing diversity in South African higher education institutions. In Diversity within diversity management, Vol. 21 (pp. 139-156). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Mukwawaya, O.Z., Proches, C.G., & Green, P. (2022). Perceived challenges of implementing an integrated talent management strategy at a tertiary institution in South Africa. International Journal of Higher Education, 11(1), 100-107. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v11n1p100 [ Links ]

Musakuro, R.N. (2022). A framework development for talent management in the higher education sector. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehulpbronbestuur, 20, a1671. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v20i0.1671 [ Links ]

Ngobeni, E.K., & Bezuidenhout, A. (2011). Engaging employees for improved retention at a higher education institution in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management, 5(23), 9961-9970. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.1381 [ Links ]

Ng'ethe, J.M., Iravo, M.E., & Namusonge, G.S. (2012). Determinants of staff retention in public universities in Kenya: Empirical review. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(13), 105-212. [ Links ]

Ngakantsi, I.S. (2022). Examining the relationship between the psychological contract, organisational commitment and employee retention in the water control sector of South Africa. Unpublished doctoral thesis. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Omodan, B.I. (2022). Analysis of 'hierarchy of needs' as a strategy to enhance academics retention in South African universities. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 11(3), 366-366. https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2022-0089 [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, R.M., Coetzee, M., & Munro, Z. (2016). Work-life balance, job satisfaction and turnover intention amongst information technology employees. Southern African Business Review, 20(1), 446-467. https://doi.org/10.25159/1998-8125/6059 [ Links ]

Peirce, G.L., Desselle, S.P., Draugalis, J.R., Spies, A.R., Davis, T.S., & Bolino, M. (2012). Identifying psychological contract breaches to guide improvements in faculty recruitment, retention, and development. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 76(6), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe766108 [ Links ]

Peltokorpi, V., Allen, D.G., & Froese, F. (2015). Organizational embeddedness, turnover intentions, and voluntary turnover: The moderating effects of employee demographic characteristics and value orientations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 292-312. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1981 [ Links ]

Potgieter, I.L., & K, Mathonsi. (2021). Organisational trust and commitment among South African public service employees: Influence of socio-demographics. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(6), 555-564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2021.2001909 [ Links ]

Psycones. (2006). Final scientific report: psychological contracts across employment situations. Socio-economic research.

Rafiee, N., Bahrami, M.A., & Entezarian, S. (2015). Demographic determinants of organizational commitment of health managers in Yazd province. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics, 2(1), 91-100. [ Links ]

Randmann, L. (2013). Managers on both sides of the psychological contract. Journal of Management and Change, 30(1), 121-144. [ Links ]

Robyn, A.M. (2012). Intention to quit amongst Generation Y academics at HEIs. Unpublished master's dissertation. Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Robyn, A.M., & Du Preez, R. (2013). Intention to quit amongst generation Y academics in higher education. South African Journal of Organisational Psychology, 39(1), 1106. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i1.1106 [ Links ]

Rousseau, D.M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organisations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01384942 [ Links ]

Rousseau, D.M. (1990). New hire perceptions of their own and their employer's obligations: A study of psychological contracts. Journal of Organisational Behavior, 11(5), 389-400. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110506 [ Links ]

Rousseau, D.M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organisations. Sage.

Rousseau, D.M. (2011). The individual-organization relationship: The psychological contract. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 3. Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (pp. 191-220). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12171-005

Setati, S.T., Zhuwao, S., Ngirande, H., & Ndlovu, W. (2019). Gender diversity, ethnic diversity and employee performance in a South African higher education institution. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v17i0.1061 [ Links ]

Snyman, A.M. (2021). A framework for staff retention in the higher education environment: Effects of the psychological contract, organisational justice and trust. Doctoral dissertation. University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Snyman, A.M. (2022). Predictors of staff retention satisfaction: The role of the psychological contract and job satisfaction. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(5), 459-465, https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2121047 [ Links ]

Snyman, A.M., Ferreira, N., & Deas, A.J. (2015). The psychological contract in relation to employment equity legislation and intention to leave in an open distance higher education institution. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 39(1), 72-92. https://doi.org/10.25159/2520-3223/5884 [ Links ]

Spector, P.E. (2019). Do not cross me: Optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 125-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8 [ Links ]

Van Stormbroek, R., & Blomme, R. (2017) Psychological contract as precursor for turnover and self-employment. Management Research Review, 40(2), 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-10-2015-0235 [ Links ]

Takawira, N., Coetzee, M., & Schreuder, D. (2014). Job embeddedness, work engagement and turnover intention of staff in a higher education institution: An exploratory study. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(1), 524. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v12i1.524 [ Links ]

Tettey, W.J. (2006). Staff retention in African Universities: Elements of a sustainable strategy. World Bank.

Theron, M., Barkhuizen, N., & Du Plessis, Y. (2014). Managing the academic talent void: Investigating factors in academic turnover and retention in South Africa. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1), 1117. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v40i1.1117 [ Links ]

Van der Vaart, L., Linde, B., & Cockeran, M. (2013). The state of the psychological contract and employees' intention to leave: The mediating role of employee well-being. South African Journal of Psychology, 43(3), 356-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246313494154 [ Links ]

Van der Vaart, L., Linde, B., De Beer, L., & Cockeran, M. (2015). Employee well-being, intention to leave and perceived employability: A psychological contract approach. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 18(1), 32-44. https://doi.org/10.17159/2222-3436/2015/v18n1a3 [ Links ]

Van Dyk, J., & Coetzee, M. (2012). Retention factors in relation to organisational commitment in medical and information technology services. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 10(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v10i2.433 [ Links ]

Van Dijk, H.G., & Ramatswi, M.R. (2016). Retention and the psychological contract: The case of financial practitioners within the Limpopo Provincial Treasury. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(2), 30-46. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Annette Snyman

snymaam@unisa.ac.za

Received: 06 June 2023

Accepted: 10 Sept. 2023

Published: 11 Dec. 2023