Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Journal of Human Resource Management

versão On-line ISSN 2071-078X

versão impressa ISSN 1683-7584

SAJHRM vol.21 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v21i0.2238

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Leadership styles as predictors of employee engagement at a selected tertiary institution

Genevieve Southgate; John K. Aderibigbe; Tolulope V. Balogun; Bright Mahembe

Department of Industrial Psychology, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: The study examined transformational leadership (TFL), transactional leadership (TSL) and servant leadership (SL) as predictors of employee engagement (EE) at a tertiary institution in Cape Town

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The study empirically investigated the predictive role of TFL, TSL and SL in EE among a university's staff in Cape Town

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: The workforce disruption known as 'The Great Resignation', in which many Americans voluntarily left their jobs during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, provides evidence of the necessity for this investigation

RESEARCH APPROACH/DESIGN AND METHOD: The study adopted the positivist philosophical view using an explanatory survey research design and a quantitative approach. The researchers sampled 198 administrative and support staff via a validated questionnaire

MAIN FINDINGS: The study showed a statistically significant collective impact of TFL, TSL and SL on EE (R2 = 0.268; F = 25.019; p < 0.01). Similarly, the study's findings revealed a statistically significant impact of TFL on EE (β = 0.269; t = 3.115; p < 0.01) and a statistically significant influence of TSL on EE (β = 0.254; t = 3.020; p < 0.01). However, the results indicated that SL did not significantly impact EE

PRACTICAL/MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: Management of tertiary institutions and supervisors should possess TFL and TSL competencies and be swift in engaging their subordinates

CONTRIBUTION/VALUE-ADD: The research outcomes provides insight into enhancing an engaged workforce and proactive measures to increase EE

Keywords: administrative and support staff; employee engagement; servant leadership; tertiary institution; transformational leadership; transactional leadership.

Introduction

Since the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, various adjustments have influenced human resource operations globally, particularly in the higher education sector. Some adjustments to accommodate employees in the new normal include organisations adopting remote working and modifying their strategies and resources (Pather et al., 2021). Specifically, South Africa has seen an unprecedented shift towards telecommuting or working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eighty-eight percent of employees regularly worked from home in 2020. By early 2021, employees in most countries, including South Africa, were still required or encouraged to work from home where possible (De Klerk et al., 2021). Surprisingly, 12.6% of employees reported being more engaged with their workplace (Bateleur's National Employment Engagement Survey, 2020). Dips in employee engagement (EE) often result in decreased employee performance and retention (Bateleur's National Employment Engagement Survey, 2020), negatively impacting a business's ability to remain stable and viable (Chiwawa & Wissik, 2021).

The workforce disruption known as 'The Great Resignation', in which many Americans voluntarily left their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic, provides evidence of this need. This is primarily because workers better understand their preferences for work environments and their unique needs regarding personal well-being and job satisfaction (Dean & Hoff, 2021). Specific reasons for resignation included demands to return to in-person work, better work-life balance or mistreatment during the pandemic (Chugh, 2021).

Employee engagement is a construct that has become crucial during this time, as it remains vital that the workforce remains committed to their jobs and that employees continue to do what they are employed to do, namely rendering and making their services available. Employee engagement includes working hard, being productive, and caring for organisational goals and employees' contributions to reaching those goals (Ahmed et al., 2020).

Given the essential role of EE in achieving organisational goals (Liu et al., 2021), it becomes crucial in this era of remote working to identify factors that promote workers' engagement while working from the comfort of their homes. Employee engagement is influenced by organisational and individual elements, including motivation, technology, personality, corporate culture and the environment (Reijseger et al., 2016). However, this study seeks to investigate the impact of transformational leadership (TFL), transactional leadership (TSL) and servant leadership (SL) on EE at a tertiary institution in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. As personal and familial responsibilities have increased, organisations' leadership teams may need to consider flexibility and adaptability relative to EE (Adhitama & Riyanto, 2020; Goswami, 2021).

Transformational leaderships aspire to take their followers on a journey of self-discovery, to be the best version of themselves, transcend their self-interest and work towards serving the organisation (Bakker et al., 2008). They have been known to inspire and challenge their subordinates to go beyond their interests for the greater good of the organisations they work for. Moreover, TFL is an avid style used by visionary leaders who have empowered followers (Othman et al., 2017).

Transactional leaderships, on the other hand, are known to cede complete control and use no specific leadership style to guide their colleagues, focusing instead on the everyday operations and tasks at hand, monitoring and controlling people based on their performance (Bakker et al., 2008). This leadership style focuses on getting employees to do their work and uses rewards or corrective measures to ensure the job is performed (Oliver, 2012). In contrast, SLs are known to be example leaders who focus on serving others first (Spears & Lawrence, 2002). Components of the SL style during the COVID-19 pandemic were found to help manage distance-working teams (Nawafah et al., 2020).

Aim of the study

To address the issues above, the study aimed to empirically investigate EE among administrative and support staff of a university in the Western Cape province as predicted by TFL, TSL and SL. Furthermore, the study specifically investigated the following objectives:

-

to examine the impact of TFL on EE

-

to investigate the impact of TSL on EE

-

to examine the impact of SL on EE

-

to determine the collective prediction of EE by TFL, TSL and SL.

Literature review

Employee engagement

Employee engagement was described by Khan (1990) as the establishment of employees in their work roles. Engaged employees use and express their physical, cognitive and emotional identities during role performance. Considering these conventional definitions, these ideas can imply that employees are primarily on-site because engagement entails psychological presence when occupying and executing an organisational job (Sinclair, 2021).

Considering the above, Khan defined EE as harnessing organisation members' selves to their work roles. In engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively and emotionally during role performances (Khan, 1990). The definitions of 'engagement' have been used interchangeably in varied research. A study on the evolutionary stages of EE includes various constructs such as personal engagement, burnout or engagement, work engagement and EE (Rather & Sharma, 2020). According to Bakker and Van Wingerden (2021), work engagement is a rewarding and motivating condition characterised by high levels of mental and physical energy, zeal for and devotion to one's work, and total immersion in one's work activities.

In a study by the Gallup EE Index in 2010 and 2017, respectively, low levels of EE were found worldwide (Motyka, 2018). These studies revealed that in 2010, approximately 33% of the workforce and in 2017, approximately 15% of workers on a global level were viewed as fully engaged in their work. The other 85% were either actively disengaged or not engaged at all. The 2022 Gallup Global Workplace Report further explains that engagement and well-being had increased internationally before the pandemic. However, they have since plateaued. The percentage of engaged workers in the United States decreased from 36% in 2020 to 34% in 2021.

In 2022, this trend persisted, with 32% of full- and part-time employees working for companies engaged and 18% actively disengaging. Most employees globally were 'watching the clock tick' and 'living for the weekend'. Only 21% of workers reported being highly engaged, whereas 33% reported being in excellent general health (Gallup, 2022; Harter, 2023). Furthermore, due to the pandemic threat, the new normal of remote working has increased workloads and working hours and disrupted the work-life balance typically found when based in an office (Goswami, 2021).

Transformational leadership and transactional leadership

Transformational leadership was first introduced by political scientist James McGregor Burns in 1978 through his publication on Leadership and has proved essential in leadership theories. Burns (1978) suggested two types of leaders: transactional and transformational. According to Burns (1978), there are two different kinds of leaders. Burns made a distinction between ordinary leaders who give followers tangible rewards in exchange for their labour and loyalty (which would later be referred to as TSL) and extraordinary leaders who interact with followers to concentrate on higher-order intrinsic needs, highlighting the significance of particular outcomes and exploring novel approaches to achieving those outcomes (Griffin, 2003; Judge & Piccolo, 2004). When leaders exhibited transformative traits, they still exercised authority; however, they did so in a way that improved the degree of human behaviour and ethical ambition of both leader and follower and hence had a transforming influence on both (Burns, 1978).

Dafe (2021) highlights that TFLs serve as examples that their followers look up to and respect. Transformational leaderships also have high expectations for the ability of those they support and mentor to perform at the required level of ability. A transformational leader is also characterised as someone with a clear, bold mission. Abasilim et al. (2019) believe TFLs inspire team members to be self-motivated, achieve their best, and surpass their perceived constraints. They referred to TFL as inspirational motivation.

On the other hand, TSL deals with actions and outcomes. According to Batista-Taran et al. (2009), no rewards would be offered if a TSL felt their employee did not perform correctly. This is evident from the definition of TSL, which is an interplay between the leader and followers to accomplish a specified aim or goal (Bass, 1985). Bass (1985) defined TSL as an exchange between the leader and follower to achieve a stated objective or goal. Oliver (2012) believes TSL encourages employees to achieve work requirements by stressing incentives or sanctions.

Although TFL and TSL are incredibly similar, both can set specific goals, define individual responsibilities, and inspire their followers to achieve those goals. The main distinction is that 'first order' transactions and exchanges are the only means of inspiration for TSLs, who also employ external rewards (Oliver, 2012, p. 31).

Servant leadership

Servant leadership was first introduced in an article written by Robert Greenleaf in 1970 titled 'The Servant as Leader', where he stated, 'The SL is servant first … It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve'. This means leaders deal with 'serving others first, to become servants themselves' (Greenleaf, 1977, pp. 8-12). According to Greenleaf (1988), people with a strong desire to serve others as their primary motivator are the ones that show genuine leadership. An additional contribution by Spears (2010) was based on Greenleaf's (1977) conceptual framework. Listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualisation, foresight, stewardship, dedication to the growth of others, and fostering community are among the 10 qualities of an SL that Spears (2010) highlighted.

Furthermore, Patterson (2003) developed values that are considered influential in shaping the attitudes, behaviours and characteristics of a servant leader and defined SLs as 'those who serve with a focus on the followers, whereby the followers are the primary concern and the organisational concerns are peripheral' (Patterson, 2003, p. 81). Agápao's love, humility, altruism, vision, trust, empowerment and service are traits of Patterson's (2003) framework.

Blanchard (2004) also contributed to the reports on SL and believed that the 'leadership' aspect of SL dealt with vision, direction and goals. Most leaders are chosen because their foresight is better than most. He concluded that Greenleaf (1977) was ahead of his time when he suggested that foresight is a better-than-average guess about what will happen.

Impact of transformational leadership on employee engagement

In a study conducted by Breevaart et al. (2014) regarding the relationship between EE and TFL and TSL in a study using 61 naval cadets during a 34-day journey, results showed that employees were more engaged on the days their leaders displayed more TFL characteristics. Schaubroeck et al. (2016) further supported these findings in their studies which found that TFL positively impacted EE and productivity.

Moreover, Yuan et al. (2012) reported that TFL significantly increased work engagement levels and service performance in a study conducted on 1980 participants (660 employees and 1320 clients) working in an Information Technology corporation in Taiwan. Similarly, TFL was positively related to employee work engagement and mediated through employee psychological capital in a study conducted with 193 sub-ordinate supervisor participants in Vietnam (Aryee et al., 2012).

Furthermore, Thanh and Quany (2022) conducted an exploratory study of 325 participants consisting of leaders and civil servants in the provincial public sector in Vietnam. This study discovered that TFL and TSL positively impacted workers' job engagement. Additionally, Obuobisa-Darko (2020), in their research study of 411 permanent employees, highlighted that TFL positively affected EE and performance indicators. Kovjanic et al. (2013) studied 190 participants in a brainstorming task under TFL and non-TFL conditions. It highlighted that TFL induced the satisfaction of employees' need for competence, autonomy and relatedness, subsequently predicting employees' engagement levels as it was found to lead to more excellent performance. A study by Jiatong et al. (2022) on 845 hotel employees in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces of China highlighted that TSL positively affected organisational commitment and job performance, mediated by EE.

Impact of transactional leadership on employee engagement

A recent study by Suhendra (2021) highlighted a significant relationship between TSL and EE in their study of 84 employees in the property sector in Sidoarjo, Indonesia. In a study of 43 managers and supervisors working in a manufacturing organisation in the North-West region of South Africa, Kersop (2019) discovered additional evidence of a positive relationship between TSL and EE. Moreover, a study of 439 sales assistants in Australia suggested that EE was negatively associated with an employee's perception of leadership style when classical or transactional (Zhang et al., 2014). A descriptive case study conducted by Adeniji et al. (2020) among 422 participants of consumer-packaged goods firms in Nigeria showed a significant and moderate relationship between TFL, TSL and EE.

Impact of servant leadership on employee engagement

In a recent study that tested 704 service sector employees in Pakistan, Khan et al. (2021) reported a positive association between SL and work engagement and meaning. Contrariwise, a study of SL's impact on employees' work engagement in academic settings at 12 Palestinian institutions showed no evidence of a direct correlation between the two. However, the association between SL and academic staff members' work engagement was moderated by mediating factors such as motivation, psychological ownership and person-job fit (Aboramadan et al., 2020).

Additionally, Canavesi and Minelli's qualitative study (2022) found a positive association between SL and EE among 151 workers in Milan's financial services sector. Also, Carter and Baghurst (2014), in their study of 11 employees in a servant-led restaurant, found a positive relationship between SL and EE which also contributed to loyalty. In his dissertation, Whorton (2014) conducted a descriptive case study between leaders and followers of 14 divisions within an international engineering company in the United States. The results only indicated a partial link between SL's impact on EE. De Clercq et al.'s (2014) study regarding work engagement and SL among IT professionals at four firms in Ukraine tested two models. The second model showed a positive relationship between SL and work engagement.

Statement of hypotheses

1. TFL will have a statistically significant positive impact on EE.

2. TSL will have a statistically significant positive impact on EE.

3. SL will have a statistically significant positive impact on EE.

4. TFL, TSL and SL will have a statistically significant interactive effect on EE.

Figure 1 below presents a hypothesised model depicting the individual and interactive impacts of TFL, TSL and SL on EE.

Research design

Research design, participants and sampling techniques

The positivist paradigm underpinned the research due to its quantitative nature and empirically basing the findings on a scientifically recommended sample size (Sekaran, 2003). Additionally, various statistical approaches were used to quantify and analyse the connections between the variables. Moreover, the researchers adopted an explanatory survey design using structured, validated questionnaires to elicit information from research participants. The dependent variable was EE, while the independent variables were TFL, TSL and SL.

One hundred and ninety-eight administrative and support staff participated in the study. Specifically, the study sample included 78 (39.4%) male and 119 (60.1%) female administrative and support staff of a public university in the Western Cape province of South Africa - one respondent preferred not to indicate their gender. The researchers used Raosoft sample size software to estimate an appropriate sample size for the study with a 5% margin of error, 95% confidence level, and 50% response distribution level. The researchers applied purposive and convenient sampling techniques to sample the research participants. The choice of purposive and convenient sampling methods was deemed appropriate for this study, as the study involved the administrative and support staff of the university only - academic staff was excluded. Moreover, reaching the study sample electronically via institutional emails and their supervisors was convenient.

Research instrument

The researchers used a standardised and validated questionnaire to ensure the validity and reliability of the data obtained. The questionnaire included the following sections: Section A - Biographical and occupational information (age, gender, marital status, years in service and position and/or grade); Section B - Work and/or engagement scale (WES-3); Section C - TSL scale; Section D - TFL scale; and Section E - SL scale.

The WES-3 was modified and revalidated by Choi et al. (2020). It was a 10-item scale designed with a response option ranging from 'never' to 'daily' rated on a 5-point Likert-type. For the EE measure, the current study's researchers obtained a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.60, while Choi et al. (2020) reported a score of 0.78. The structural validity of WES-3 scores was evaluated by Choi et al. (2020), employing Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Confirmatory Factor Analysis was used to test the construct validity of work engagement. The World Health Organization-Five well-being index (WHO-5), which consists of three items measuring job engagement and two items measuring burnout, was used to measure the convergent validity (χ2: 382.05, Tucker-Lewis index: 0.984, comparative fit index: 0.994, root mean square error of approximation: 0.043). The convergent validity was significant (correlation coefficient: 0.42) (Choi et al., 2020).

The TFL scale used was a 7-item modified version of the global transformational leadership (GTL) scale, developed and verified by Van Beveren et al. (2017). The scale was designed with a 5-point Likert response type ranging from range (1 = 'never') to (5 = 'daily'). While Van Beveren et al. (2017) reported a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient score of 0.70 for the TFL scale, the current study's researchers obtained a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.75.

The researchers adapted the 12-item TSL scale, developed and verified by Jensen et al. (2019). The 12-item scale reflects three TSL components: pecuniary rewards, non-pecuniary rewards and contingent sanctions. The scale was designed with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1 = 'never') to (5 = 'daily'). The validity and reliability of the TSL scale were tested using a CFA. They were reported to have a Cronbach's alpha reliability threshold of 0.70 for composite constructs (Jensen et al., 2019). The current study obtained a Cronbach alpha's reliability coefficient score of 0.73 for the TFL scale.

Lastly, the questionnaire also contained a 7-item shortened version of the SL questionnaire, adapted and re-validated by Grobler and Flotman (2020). The statements in the 7-item SL scale were designed with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1 = 'never') to (5 = 'daily'). In addition, the 7-item shortened version was also found suitable for use across different samples, including the private and public sectors, and could be used confidently within the South African context (Grobler & Flotman, 2020). As reported in the literature, the reliability scores of the SL scale ranged from 0.80 to 0.89 (Grobler & Flotman, 2020; Liden et al., 2015). However, the current study's researchers obtained a Cronbach alpha's reliability score of 0.71 for the 7-item shortened version of the SL scale.

Data collection procedure

The research commenced with an application for ethical clearance. The researchers sought and obtained ethical approval (Ethics reference number: HS21/9/10) for the study from the University Research and Ethics Committee. Moreover, the researchers obtained a permit (… 5133759182537637031) from the institution's management to involve the administrative and support staff in the study. The field work started on 21 April 2022. Due to the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) and the many restrictions in retrieving the personal information, the researchers could not access the employee master file directly and needed to use the research permanent (research perm) mailbox. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, the researchers used the Google Form link to administer the questionnaire via the research perm mailbox to all the university's permanent administrative and support staff.

The first data collection phase started well, with many participants responding during the first month of fieldwork. After that, the link was re-sent via the research perm mailbox on 02 and 12 May 2022 as reminders. However, during the subsequent months, responses slowed tremendously, with 103 responses received by 17 June 2022. Nonetheless, to ensure that the targeted sample responds to the questionnaire, the researchers also requested the assistance of the Executive Members of the Human Resources, Finance, and Services departments, various Heads of Departments as well as the Human Resources Consultants at the institution, who then helped to follow-up with their respective administrative and support staff members. This yielded additional responses, with 148 responses received on 04 August 2022.

In a final attempt to attract an adequate sample, the researchers sent reminders to the institution's Executive members and Human Resources consultants on 09 September 2022. This proved fruitful, as another 59 participants responded to the online questionnaire, yielding 207 responses. Additional attempts were undertaken to review the 207 questionnaires and find any respondents who did not fully complete the questionnaire to assure the accuracy and reliability of the data acquired. Out of the 207 questionnaires recovered, the screening findings showed that nine were either incomplete or belonged to the institution's academic staff, which were not included in the administrative and support employee sample. Consequently, the remaining 198 questionnaires that were verified in order were kept, and the other nine questionnaires were destroyed. The data cleaning process commenced on 15 September 2022. All data collected were kept safe on an external hard drive, protected through a password-protected folder.

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 was used to analyse the data in light of the stated hypotheses. In addition, the biographical and occupational variables' percentages, means, standard deviations and frequencies were computed as part of the data analysis using descriptive statistical techniques. Additionally, percentages were shown on frequency tables and graphical representations to provide information on demographic features. On the other hand, hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 4 were analysed through multiple regression analysis. Multiple regression analysis was considered appropriate to draw EE's individual and collective predictions by TFL, TSL and SL. In addition, Pearson correlation analysis was also applied to test the intercorrelation between EE, TFL, TSL and SL.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the University of the Western Cape Humanities and Social Science Research Ethics Committee (No. HS21/9/10).

Results

The statistical analysis results are presented in the tables provided in this article, including a model depicting the results of the hypotheses tested.

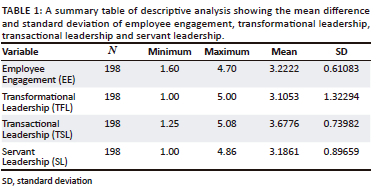

The results in Table 1 reveal an overall mean score of 3.22 (SD = 0.61) for EE. This shows a positive perception of EE. Similarly, the descriptive statistics reveal a mean score of 3.10 (SD = 1.32) for TFL. In addition, the descriptive statistics show an overall mean score of 3.67 (SD = 0.73) for TSL and an overall mean score of 3.18 (SD = 0.89) for SL.

Reliability test of the scales

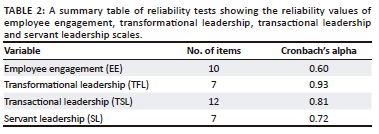

The results in Table 2 show the number of items in each of the four measurement scales applied in the study. The results indicate that the EE scale obtained an acceptable reliability value (α = 0.60), the TFL scale obtained a very strong reliability value (α = 0.93), the TSL scale obtained a very strong reliability value (α = 0.81), and the SL scale obtained a strong reliability value (α = 0.72). This implies that the psychometric properties of the research instruments were sufficient. The study also tested TFL, TSL, SL and EE correlations. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 3.

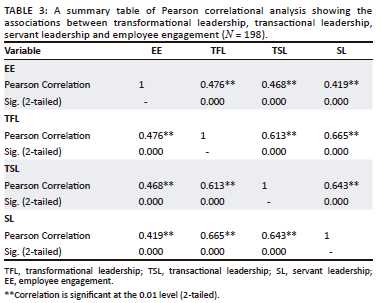

The results in Table 3 show a moderately significant positive relationship between EE and TFL behaviour (r = 0.476, p < 0.01), a moderately significant positive relationship between EE and TSL behaviour (r = 0.468, p < 0.01), and a moderately significant positive relationship between EE and SL (r = 0.419, p < 0.01). This implies that with an increase in transformational, transactional and SL behaviours, there is a corresponding increase in EE.

The results in Table 3 further revealed other existing associations. Transformational leadership and TSL have a statistically significant positive connection (r = 0.613, p < 0.01); TFL and SL have a statistically significant positive association (r = 0.665, p < 0.01) and TSL and SL have a statistically significant positive association (r = 0.643, p < 0.01). This confirms the interrelatedness of transformational, transactional and SL behaviours.

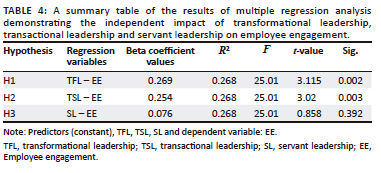

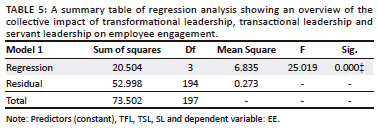

Hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 4 were tested using multiple regression analysis to statistically determine whether TFL, TSL and SL significantly predicted EE. The results of hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 are presented in Table 4.

The results in Table 4 show that EE was regressed on TFL, TSL and SL. The results show that for a unit increase in the TFL score, there is a corresponding increase in EE (b = 0.269; p-value 0.002) when transactional and SL behaviours are controlled. This demonstrates that TFL behaviour positively impacts EE. As a result, a rise in a leader's transformational behaviour would be accompanied by a rise in followers' levels of EE. Subsequently, based on the results and interpretations above, hypothesis 1, which stated that TFL would have a significant positive impact on EE, is accepted.

Moreover, controlling for the other variables in the model, namely, TFL and SL (TFL + SL), the results show that a unit increase in TSL stimulates a corresponding increase in EE (b = 0.254; p = 0.003). This indicates that TSL significantly and positively impacts EE. In other words, the relationship between TSL and EE is structured so that an observed rise in one is correlated with a rise in the other. Hence, hypothesis 2, which stated that TSL would significantly impact EE, is accepted. However, the results in Table 4 reveal that SL does not significantly impact EE (b = 0.076; p = 0.392). Hence, hypothesis 3, which stated that SL would significantly impact EE, is rejected. The results of hypothesis 4 are presented in Table 5.

Finally, the results in Table 4 and Table 5 show that the analysis of variance for the regression yielded an F-ratio of 25.019 and a coefficient of an adjusted R2 of 0.268, which indicates the interactive effect of transformational, transactional and SL behaviours explain 26.8% of the variance in EE. The significance of the composite contribution was tested at p < 0.001. This implies that EE was significantly collectively predicted by transformational, transactional and SL behaviours, confirming hypothesis 4, which stated that TFL, TSL and SL will have a statistically significant interactive effect on EE. Figure 2 depicts the model of the independent and interactive effects of TFL, TSL and SL on EE.

Figure 2 presents an empirically confirmed model depicting the individual and interactive impacts of TFL, TSL and SL on EE.

Discussion

The study empirically investigated the impact of TFL, TSL and SL on EE at a tertiary institution in the Western Cape. Research questions were formulated, four hypotheses were stated and tested during the study, and the results are discussed in this section. According to the study's findings, hypothesis one, which stated that TFL would significantly positively impact EE, was accepted. The results thus confirmed a positive association between TFL and EE, which implies that employees were optimally engaged in their work when their leaders displayed the characteristics of a TFL. This explains that TFLs interact with their followers as whole people rather than 'just' employees.

Moreover, TFLs understand the complexities that make up a whole individual, which range from their passions, the level of emotional support required, and what is required to allow their best ideas to come to the forefront. It speaks to an individual's distinctive humanity. Therefore, based on the researchers' understanding of the results, it was inferred that the higher education institution leaders understood the various complexities and challenges experienced by their staff during the new normal and responded appropriately. For instance, the university's staff saw their leaders as role models who had high expectations for their capacity to be effective while working remotely in the new normal. They could still receive the assistance and direction they needed from their leaders to produce the appropriate levels of performance (Dafe, 2021). This further exemplifies how TFLs encourage their followers to put the organisation's interest ahead of their self-interest (Bakker et al., 2003). This is consistent with Tims et al.'s (2011) study on 42 workers from two consulting firms in the Netherlands. The study's findings support that TFL favours EE because they can inspire, motivate and pay close attention to their workforce requirements. This also reiterates Khan's (1990) and Aon Hewitt's (2013) theories of EE, which speak to employees' emotional investment and intellectual involvement while they perform their duties. The Deloitte engagement model also highlights the need for a supportive management structure with a positive work environment.

Similarly, the analysis results confirmed that hypothesis 2, which stated that TSL would significantly positively impact EE, was correct. In other words, the findings supported the hypothesised positive impact of TSL on EE. In other words, concerning the employees at the higher education institution in the present study, the administrative and support staff displayed an increased level of EE when their leaders displayed TSL characteristics. The research outcomes imply that employee professional and personal development is critical to increasing their commitment to duties and official responsibilities. For example, when employees can pursue their self-interests and the organisation's interests simultaneously, they are known to have higher levels of engagement. Additionally, institutions that encourage a positive and flexible work environment focusing on a holistic EE experience create an environment with high engagement levels (Bersin, 2015).

Concerning the administrative and support staff, perhaps the work environment during the new normal allowed employees to focus on their interests while still contributing and exceeding their professional and organisational goals. Gemeda and Lee (2020) confirmed these views in a study of 147 Ethiopian and 291 South Korean participants working in an Information and Communications technology firm. The results highlighted that TSL positively impacted employees' task performance, mediated by EE. Additionally, Ariussanto et al. (2020) investigated TSL and EE among 50 employees in a manufacturing company and found that TSL positively impacted EE. A study of 368 respondents from public schools in Muranga, Kenya, by Maundu et al. (2020) found TSL to positively and significantly affect EE and its dimensions. Metzler (2006) similarly concluded this in their study, highlighting that TSL impacted EE positively.

However, the current study's findings proved hypothesis three incorrect. The hypothesis stated that TSL would positively impact EE. The results show no significant impact of TSL on EE. The outcome is unexpected, given that studies have shown a beneficial effect of SL on EE. Perhaps the higher education institution employees did not receive support from their organisation or leader. This could negatively impact their engagement levels. A few traits embody an SL: listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, foresight, stewardship, conceptualisation, community building and dedication to progress (Grobler & Flotman, 2020).

Lastly, hypothesis four indicated that TFL, TSL and SL would significantly collectively predict EE. Interestingly, the study's findings show that EE was significantly collectively predicted by TFL, TSL and SL, confirming the hypothesis. The results suggest that the administrative and support staff have benefited from a diversified management team that includes leaders with transformational, transactional and SL qualities. Such team compositions are advantageous to performance as their combined effort yields a more desirable result in assured EE. Hoch et al.'s (2018) meta-analysis of ethical, authentic and SL research indicated a 12.1% larger incremental variation in the link between SL and engagement. In addition, in their study, Zeeshan et al. (2021) examined 401 workers from Pakistani financial firms for a year. The study's findings demonstrated that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between SL and EE. Lastly, Nelson and Shraim (2014) indicated a significant but small positive relationship between TFL and behaviours and work engagement.

Implication

The present study's findings highlighted that leadership practices are circumstantial. The leadership style displayed is determined by context and circumstance, which will impact levels of EE differently. When understanding the positive and negative implications of the selected leadership styles, line managers and leaders can adapt accordingly to ensure that EE levels remain high. Although the current study's findings are limited to one higher education institution in the Western Cape, researchers, management, the government, and academics can make some deductions from the findings. Every workplace in the globe experienced disruption due to the COVID-19 outbreak, and EE was affected because it proved to be a difficult period. Enhancing staff engagement strategies would increase engagement levels, enhance overall output, and ultimately help this higher education institution accomplish its goals and objectives.

Moreover, by understanding how selected leadership styles affect EE during the new normal, human resource departments and line management can be sure that there will be higher levels of EE based on TFL and TSL styles during the new normal. Coaching on leadership styles is necessary for all line managers and senior leaders to understand their leadership styles. Furthermore, incorporating leadership profiles in recruitment and selection processes is sacrosanct to ensure leaders know the leadership styles displayed. It is crucial to provide relevant training interventions to ensure the workforce remains engaged and leaders are given the necessary coaching and mentoring skills to lead effectively. Also, new and alternative engagement strategies could be pertinent to keep employees engaged in their work.

Limitations and future direction

Data available on EE levels during COVID-19 is one limitation. While existing literature contains many aspects of EE, varied findings around EE as experienced by employees based on selected leadership styles in the new world of work are limited. Moreover, the questionnaires used in this study were self-reported instruments, which could be biased and skew the results. While adequate for statistical testing, the number of participants in this study represented a relatively low response rate. The selection of a larger sample could have better enhanced the external validity. The study was based on one institution of higher learning only. This limits the relatedness of the study's findings to the situations in other institutions of higher learning.

Conclusion

Leadership and their employees' contribution remain vital to any organisation's success. Leaders who can motivate and inspire their staff can increase EE. In addition, when a leader makes the development of their employees a priority, it leaves employees feeling empowered and recognised, which also impacts EE.

The study's findings, discussions and implications indicate a positive and significant impact between TFL and TSL on EE among administrative and support staff at the selected higher education institution within the Western Cape, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, no significant impact was reported between SL and EE. The researchers hope that the findings, recommendations and implications of the present research will contribute to aiding future workforces with the knowledge to remain optimally engaged. Leadership teams can motivate, inspire and encourage the workforce continually.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study would like to acknowledge all the research participants and appreciate the invaluable information provided in the course of the field work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

G.S. designed and developed the research concepts, writing and compilation of reports, data collection, analysis and presentation of results. J.K.A. supervised all the activities mentioned above. B.M. and T.V.B. contributed to manuscript preparation.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the lead author, (G.S.), upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Abasilim, U.D., Gberevbie, D.E., & Osibanjo, O.A. (2019). Leadership styles and employees commitment: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. SAGE Open, 9(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019866287 [ Links ]

Aboramadan, M., Dahleez, K., & Hamad, M. (2020). Servant leadership and academics' engagement in higher education: Mediation analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 42(6), 617-633. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2020.1774036 [ Links ]

Adeniji, A., Osibanjo, A., Salau, O., Atolagbe, T., Ojebola, O., Osoko, A., Akindele, R., & Edewor, O. (2020). Leadership dimensions, employee engagement and job performance of selected consumer-packaged goods firms. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 7(1), 1801115. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2020.1801115 [ Links ]

Adhitama, J., & Riyanto, S. (2020). Maintaining employee engagement and employee performance during COVID-19 pandemic at PT Koexim Mandiri Finance. Journal of Research in Business Management, 8, 6-10. [ Links ]

Ahmed, T., Khan, M.S., Duangkamol, T., Yananda, S.I., & Tawat, P. (2020). Impact of employees engagement and knowledge sharing on organisational performance: A study of HR challenges in COVID-19 pandemic. Human Systems Management, 39(4), 589-601. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-201052 [ Links ]

Ariussanto, K.A.P., Tarigan Z.J.H., Sitepu R.B., & Singh S.K. (2020). Leadership style, employee engagement, and work environment to employee performance in manufacturing companies. SHS Web of Conference, 76, 01020. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20207601020 [ Links ]

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F.O., Zhou, Q., & Hartnell, C.A. (2012). Transformational leadership, innovative behaviour, and task performance: Test of mediation and moderation processes. Human Performance, 25(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2011.631648 [ Links ]

Bakker, A.B., & Van Wingerden, J. (2021). Do personal resources and strengths use increase work engagement? The effects of a training intervention. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(1), 20-30. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000266 [ Links ]

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2003). Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands: Resources model. European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 12(4), 393-417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320344000165 [ Links ]

Bakker, A.B., Schaufeli, W.B., Leiter, M.P., & Taris, T.W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3), 187-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393649 [ Links ]

Bass, B.M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

Bateleur's National Employment Engagement Survey. (2020). Retrieved from https://bateleurbp.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Lockdown-Unlocks-Employee-Engagement.pdf

Batista-Taran, L., Shuck, M., Gutierrez, C., & Baralt, S. (2009). The role of leadership style in employee engagement. In M.S. Plakhotnik, S.M. Nielsen, & D.M. Pane (Eds.), Proceedings of the Eighth Annual College of Education & GSN Research Conference (pp. 15-20). Florida International University. Retrieved from http://coeweb.fiu.edu/research_conference

Bersin, J. (2015). Becoming irresistible: A new model for employee engagement. Deloitte Review, 16, 146-163. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/deloitte-review/issue-16/employee-engagement-strategies.html [ Links ]

Blanchard, K.H. (2004). Leadership smarts. David C Cook.

Breevaart, K., Bakker, A., Hetland, J., Demerouti, E., Olsen, O.K., & Espevik, R. (2014). Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 87(1).138-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12041 [ Links ]

Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row.

Canavesi, A., & Minelli, E. (2022). Servant leadership: A systematic literature review and network analysis. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 34, 267-289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-021-09381-3 [ Links ]

Carter, D., & Baghurst, T. (2014). The influence of servant leadership on restaurant employee engagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 453-464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1882-0 [ Links ]

Chiwawa, N., & Wissink, H. (2021). Determinants of employee engagement in the South African Hospitality Industry during COVID-19 lockdown epoch: Employee perception. African Journal of Hospitality Tourism and Leisure, 10(2), 487-499. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720.113 [ Links ]

Choi, M., Suh, C., Choi, S.P., Lee, C.K., & Son, B.C. (2020). Validation of the work engagement Scale-3, used in the 5th Korean Working Conditions Survey. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 32(1), e27. https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2020.32.e27 [ Links ]

Chugh, A. (2021). What is the great resignation and what can we learn from it? World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/what-is-the-great-resignation-and-what-can-we-learn-from-it/

Dafe, P.U. (2021). The influence of transformational leadership and organisational climate on organisational citizenship behaviour among support staff at a selected university in the Western Cape province. Master's thesis, University of the Western Cape Repository. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11394/8999 [ Links ]

De Clercq, D., Bouckenooghe, D., Raja, U., & Matsyborska, G. (2014). Servant leadership and work engagement: The contingency effects of leader-follower social capital. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 183-212. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21185 [ Links ]

De Klerk, J.J., Joubert, M., & Mosca, H.F. (2021). Is working from home the new workplace panacea? Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for the future world of work. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 47, a1883. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v47i0.1883 [ Links ]

Dean, G., & Hoff, M. (2021). Nearly three-quarters of workers are actively thinking about quitting their job, according to a recent survey. Business Insider Africa. Retrieved from https://africa.businessinsider.com/news/nearly-three-quarters-of-workers-are-activelythinking-about-quitting-their-job/0hw75ry

Gallup. (2022). State of the global workplace. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace-2022-report.aspx#ite-393218

Gemeda, H., & Lee, J. (2020). Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: A cross-national study. Heliyon, 6(4), E0369. https://doi.e0369910.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e0369 [ Links ]

Goswami, B.K. (2021). Employee engagement and work-life balance with the moderating effect of ethical leadership: An empirical exploration. EFFLATOUNIA-Multidisciplinary Journal, 5(2), 11104-11118. [ Links ]

Greenleaf, R. (1970). The servant as leader. The Robert K. Greenleaf Center.

Greenleaf, R. (1988). Spirituality as leadership. The Robert K. Greenleaf Center.

Greenleaf, R.K. (1977). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press.

Griffin, D. (2003). Leaders in museums: Entrepreneurs or role models? International Journal of Arts Management, 5(2), 4-14. [ Links ]

Grobler, A., & Flotman, A.P. (2020). The validation of the servant leadership scale. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46, a1754. https://doi.org/10.4102/SAJIP.V46I0.1754. [ Links ]

Harter, J. (2023). U.S. Employee Engagement Needs a Rebound in 2023. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/468233/employee-engagement-needs-rebound-2023.aspx

Hewitt, A. (2013). Trends in global employee engagement highlights. AON Hewitt report highlights (pp. 1-8). Retrieved from www.aon.com/attachments/human-capital-consulting/2013_Trends_in_Global_Employee_Engagement_Highlights.pdf

Hoch, J.E., Bommer, W.H., Dulebohn, J.H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44(2), 501-529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316665461 [ Links ]

Jensen, U.T., Andersen, L.B., Bro, L.L., Bøllingtoft, A., Eriksen, T.L.M., Holten, A.-L., Jacobsen, C.B., Ladenburg, J., Nielsen, P.A., Salomonsen, H.H., Westergård-Nielsen, N., & Würtz, A. (2019). Conceptualizing and measuring transformational and transactional leadership. Administration & Society, 51(1), 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716667157 [ Links ]

Jiatong, W., Wang, Z., Alam, M., Murad, M., Gul, F., & Gill, S.A. (2022). The impact of transformational leadership on affective organisational commitment and job performance: The mediating role of employee engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.831060 [ Links ]

Judge, T.A., & Piccolo, R.F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of applied psychology, 89(5), 755. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755 [ Links ]

Kersop, S.J. (2019). The influence of leadership style on employee engagement in a manufacturing company in the Northwest Province of South Africa. Doctoral dissertation, North-West University (South Africa). [ Links ]

Khan, M.M., Mubarik, M.S., Ahmed, S.S., Islam, T., Khan, E., Rehman, A., & Sohail, F. (2021). My meaning is my engagement: Exploring the mediating role of meaning between servant leadership and work engagement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(6), 926-941. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-08-2020-0320 [ Links ]

Khan, W.A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692-724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287 [ Links ]

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S.C., & Jonas, K. (2013). Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 86(4), 543-555. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12022 [ Links ]

Liden, R.C., Wayne, S.J., Meuser, J.D., Hu, J., Wu, J., & Liao, C. (2015). Servant leadership: Validation of a short form of the SL-28. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 254-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002 [ Links ]

Liu, D., Chen, Y., & Li, N. (2021). Tackling the negative impact of COVID-19 on work engagement and taking charge: A multi-study investigation of frontline health workers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(2), 185-198. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000866 [ Links ]

Maundu, M., Namusonge, G.S., & Simiyu, A.N. (2020). Effect of transactional leadership style on employee engagement. The Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management, 7(4), 963-974. [ Links ]

Metzler, J.M. (2006). The relationships between leadership styles and employee engagement (p. 2967). Master's theses, San Jose State University. [ Links ]

Motyka, B. (2018). Employee engagement and performance: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Management and Economics, 54(3), 227-244. https://doi.org/10.2478/ijme-2018-0018 [ Links ]

Nawafah, S., Naqrash, M., & Al-amaera, A. (2020). The role of leadership in supporting employee performance during COVID-19 Quarantine. Test Engineering and Management, 83, 3304-3319. Retrieved from https://doi.org.www.researchgate.net/publication/348447909 [ Links ]

Nelson, S.A., & Shraim, O. (2014). Leadership behaviour and employee engagement: A Kuwaiti services company. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 14(1-3), 119-135. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2014.068078 [ Links ]

Obuobisa-Darko, T. (2020). Leaders' behaviour as a determinant of employee performance in Ghana: The mediating role of employee engagement. Public Organization Review, Springer, 20(3), 597-611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-019-00460-6 [ Links ]

Oliver, W. (2012). The impact of leadership styles on employee engagement in a large retail organisation in the Western Cape. Master's thesis, UWC Scholar ETD Repository. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11394/5067 [ Links ]

Othman, A.K., Hamzah, M.I., Abas, M.K., & Zakuan, N.M. (2017). The influence of leadership styles on employee engagement: The moderating effect of communication styles. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences, 4(3), 107-116. https://doi.org/10.21833/ijaas.2017.03.017 [ Links ]

Pather, S., Lawack, V., & Brown, V. (2021). An evidence-based approach to learning and teaching during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. UWC Repository. Retrieved from https://repository.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/10566/6015

Patterson, K. (2003). Servant leadership: A theoretical model. Graduate School of Business, Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Beach, CA: Regent University.

Rather, R., & Sharma, V. (2020). Journey of engagement: From personal engagement to employee engagement. A conceptual review. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(3), 10622-10638. Retrieved from http://sersc.org/journals/index.php/IJAST/article/view/27145 [ Links ]

Reijseger, G., Peeters, M.C.W., Taris, T.W., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2016). From motivation to activation: Why engaged workers are better performers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(2), 117-130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9435-z [ Links ]

Schaubroeck, J.M., Lam, S.S., & Peng, A.C. (2016). Can peers' ethical and transformational leadership improve co-workers' service quality? A latent growth analysis. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 133, 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.02.002 [ Links ]

Sekaran, U. (2003). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

Sinclair, S. (2021). Why employee engagement and motivation are inextricably linked [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.talkfreely.com/blog

Spears, L.C. (2010). Servant leadership and Robert K. Greenleaf's legacy. Servant Leadership: Developments in Theory and Research, 1, 11-24. [ Links ]

Spears, L.C., & Lawrence, M. (2002). Focus on leadership: Servant leadership for the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons.

Suhendra, R. (2021). Role of transactional leadership in influencing motivation, employee engagement, and intention to stay. KnE Social Sciences, 5(5), 194-210. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v5i5.8809 [ Links ]

Thanh, N.H., & Quang, N.V. (2022). Transformational, transactional, laissez-faire leadership styles and employee engagement: Evidence from Vietnam's Public Sector. Sage Open, 12(2), 21582440221094606. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221094606 [ Links ]

Tims, M., Bakker, A.B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2011). Do transformational leaders enhance their followers' daily work engagement? The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.011 [ Links ]

Van Beveren, P., Dórdio Dimas, I., Renato Lourenço, P., & Rebelo, T. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Global Transformational Leadership (GTL) scale. Revista De Psicología Del Trabajo Y De Las Organizaciones, 33(2), 109-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpto.2017.02.004 [ Links ]

Whorton, K.P. (2014). Does servant leadership positively influence employee engagement? Grand Canyon University/ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Yuan, B.J.C, Lin, M., Jia-Horng, S., & Kuang-Pin, L. (2012). Transforming employee engagement into long-term customer relationships: Evidence from information technology salespeople in Taiwan. Social Behaviour & Personality: An International Journal, 40(9), 1549-1553. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.9.1549 [ Links ]

Zeeshan, S., Ng, S.I., Ho, J.A., & Jantan, A.H. (2021). Assessing the impact of servant leadership on employee engagement through the mediating role of self-efficacy in the Pakistani banking sector. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1963029. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1963029 [ Links ]

Zhang, T., Avery, G.C., Bergsteiner, H., & More, E. (2014). The relationship between leadership paradigms and employee engagement. Journal of Global Responsibility, 5(1), 4-21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-02-2014-0006 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

John Aderibigbe

johnaderibigbe1@gmail.com

Received: 28 Jan. 2023

Accepted: 05 June 2023

Published: 30 Aug. 2023