Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Journal of Industrial Psychology

versión On-line ISSN 2071-0763

versión impresa ISSN 0258-5200

SA j. ind. Psychol. vol.45 no.1 Johannesburg 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1612

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Authentic leadership and work engagement: The indirect effects of psychological safety and trust in supervisors

Natasha Maximo; Marius W. Stander; Lynelle Coxen

Optentia Research Focus Area, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: The orientation of this study was towards authentic leadership and its influence on psychological safety, trust in supervisors and work engagement.

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of authentic leadership on trust in supervisors, psychological safety and work engagement. Another aim was to determine whether trust in supervisors and psychological safety had an indirect effect on the relationship between authentic leadership and work engagement. An additional objective was to determine if authentic leadership indirectly influenced psychological safety through trust in supervisors.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Globally, businesses are faced with many challenges which may be resolved if leaders are encouraged to be more authentic and employees more engaged. In this study, investigating the role of trust in supervisors and psychological safety on the relationship between authentic leadership and work engagement is emphasised.

RESEARCH DESIGN, APPROACH AND METHOD: This study was quantitative in nature and used a cross-sectional survey design. A sample of 244 employees within the South African mining industry completed the Authentic Leadership Inventory, Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, Workplace Trust Survey and Psychological Safety Questionnaire.

MAIN FINDINGS: The results indicated that authentic leadership is a significant predictor of both trust in supervisors and psychological safety. This study further found that authentic leadership had a statistically significant indirect effect on work engagement through trust in supervisors.

PRACTICAL OR MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The main findings suggest that having more authentic leaders in the mining sector could enhance trust in these leaders. Authentic leadership thus plays an important role in creating a positive work environment. This work environment of authenticity and trust could lead to a more engaged workforce.

CONTRIBUTION OR VALUE-ADD: Limited empirical evidence exists with regard to the relationship between authentic leadership, work engagement, psychological safety and trust in supervisors. This is particularly true in the mining sector. This study aimed to contribute to the limited number of studies conducted.

Keywords: Authentic leadership; trust in supervisor; work engagement; psychological safety; mining industry.

Introduction

Because of continuous changes in the global business environment, organisations are facing numerous challenges. These challenges may result in many organisations experiencing economic and ethical meltdowns (Deloitte, 2014; George, Sims, McLean, & Mayer, 2007). In particular, South African mining companies are experiencing cost pressures and constraints which place tremendous strain on the mining industry. The daily operations of mines are further adversely affected by the continual shortage of frontline and professional skills within South Africa (Deloitte, 2014). As experienced personnel retire or leave the supply of experienced skills in frontline positions, such as supervisors, the workforce is placed under tremendous pressure. This has a direct effect on production output, quality and safety while further increasing overhead costs (Deloitte, 2014).

Changing the type of leadership and the way that mining employees perceive their leaders could assist in addressing the challenges experienced in the mining industry (Breytenbach, 2017). Leaders should display integrity, strong values and purpose as well as the ability to develop durable organisations through the motivation of subordinates (Breytenbach, 2017). Integrity and authenticity are widely regarded as highly important societal values and are important components of effective leadership (George et al., 2007). Leaders should be open and transparent as well as cognisant of the effects that their actions might have on others. They should further be aware of the internal and external influences and processes of an organisation (Clapp-Smith, Vogelgesang, & Avey, 2009). If they possess these behaviours, subordinates will be able to identify with the organisation's goals and challenges (Clapp-Smith et al., 2009). When subordinates perceive their supervisors to possess the necessary skills and abilities to facilitate growth and productivity within the organisation, it leads to an increased assurance among subordinates of a better and more profitable future in the organisation (Hassan & Ahmed, 2011). This may result in an increase in work engagement as subordinates gain a sense of trust and feelings of safety in the capabilities and competence of their supervisors (Hassan & Ahmed, 2011).

For the purposes of this study, authentic leadership as a form of positive leadership will be focused on (Stander & Coxen, 2017) as it has been found to have a positive effect on many organisational and employee behaviours (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Coxen, Van der Vaart, & Stander, 2016). These behaviours may include psychological safety, trust in supervisors and work engagement.

The topic of authentic leadership has become more prominent in recent years in both practical and academic fields (Agote, Aramburu, & Lines, 2015; Coxen et al., 2016; Du Plessis & Boshoff, 2018; Shamir & Eilam-Shamir, 2018; etc.). Previous studies have indicated that authentic leadership may have a positive effect on psychological safety (Eggers, 2011), trust in supervisors (Caldwell & Dixon, 2010; Coxen et al., 2016) and work engagement (Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008; Walumbwa, Wang, Wang, Schaubroeck, & Avolio, 2010). Although studies have been conducted to link authentic leadership with certain behavioural outcomes, the indirect effects of some of these outcomes have not been empirically tested in the South African mining context. The indirect effects of psychological safety have been tested (Lyu, 2016), but not as a mechanism through which authentic leaders influence subordinate behaviour. According to Hsieh and Wang (2015), trust fully mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and employee engagement. It would be interesting to determine if these findings can also be replicated in a South African context, with particular reference to the mining industry. The specific model (including the constructs) indicated in this study has not yet been empirically tested in a South African mining organisation. Work engagement is often regarded as an important employee outcome in ensuring optimal performance (Breevaart, Bakker, Demerouti, & Derks, 2015).

The purpose of this study was, therefore, to: (1) examine the effects of authentic leadership on trust in supervisors, psychological safety and work engagement; (2) investigate whether psychological safety and trust in the supervisor indirectly affect the relationship between authentic leadership and work engagement; and (3) determine whether trust in the supervisor indirectly affects the relationship between authentic leadership and psychological safety.

Literature review

Authentic leadership

According to Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May and Walumbwa (2005), authentic leadership can be described as the process whereby leaders are aware of their thoughts and behaviours within the context in which they operate. Authentic leaders are often aware of their own leader and subordinate values, moral perspectives, strengths and knowledge (Avolio & Luthans, 2006). They are regarded as mindful of both their own personal authenticity and the manner in which they allow subordinates to achieve common goals and objectives (Clapp-Smith et al., 2009).

Recent studies suggested that authentic leadership is a 'higher-order, multidimensional construct, comprised of self-awareness, balanced processing, the internalisation of moral and ethical perspectives and relational transparency' (Walumbwa et al., 2008, p. 89). Self-awareness refers to leaders' knowledge of themselves, their mental state and the perceived image they have of themselves (Gardner et al., 2005; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011), whereas balanced processing refers to a leader's ability to consider and analyse all relevant facts objectively before making a decision (Gardner et al., 2005; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011). Possessing a moral perspective is when leaders rely on their own morals, values and standards to drive their actions, irrespective of external pressures (Gardner et al., 2005; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011). Finally, relational transparency refers to these leaders' ability to express their true thoughts and motives, facilitating their ability to openly share information (Gardner et al., 2005; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011).

Authentic leadership is focused on a leader's relationship with his or her subordinates (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Wong & Cummings, 2009). A fair number of leadership theories emphasise a leader's behaviours and characteristics; however, very few leadership theories focus on the relationship between leaders and subordinates (Wong & Cummings, 2009). Even though authentic leadership has a significant focus on the relational transparency and self-awareness of leaders, it also focuses on personal and social identification (Wong & Cummings, 2009). Authentic leadership views personal and social identification as processes through which the behaviour of a leader results in self-awareness among the leaders and subordinates (Wong & Cummings, 2009).

A positive moral perspective and balanced processing are important components of authentic leadership (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011). Leaders need to objectively consider all of the facts to engage in ethical and transparent decision-making; therefore, authentic leaders utilise their own moral capacity and resilience to confront and deal with ethical dilemmas and make moral decisions. Making decisions in a fair and moral manner is crucial given the nature of change in social, political and business environments (Sarros & Cooper, 2006). The nature of these environments makes it important to rely on leaders who are genuine and possess moral attributes.

Because of the high moral standards, integrity and honesty displayed by authentic leaders, subordinates may develop positive expectations as well as increased levels of trust and a stronger willingness to cooperate with leaders to the benefit of the organisation (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004; Wang & Hsieh, 2013). This is confirmed by Caldwell and Dixon (2010), who found that authentic leaders influence individuals at various levels in an organisation. Authentic leaders thus have a significant impact on both their subordinates and the organisations that they lead.

Trust in supervisors

Although building stronger trust in leaders is required to address the many challenges faced by organisations, trust continues to be low in organisations (Gallup, 2012). To foster trust in supervisors, leadership that impacts the entire organisation in a positive manner is required. To achieve such leadership, loyalty, commitment and the willingness to take risks should be the important characteristics of organisational members. The above-mentioned characteristics can only be achieved if leaders instil extensive trust within their subordinates.

According to Agote et al. (2015), trust in a leader will have an effect on subordinates' work attitudes and behaviours. Trust can be defined as the disposition of an individual to be vulnerable to the actions of another while believing that the other will conduct a specific action (with good intentions) - this action should be important to the trustor (Clapp-Smith et al., 2009; Roussin, 2008). Trust is also the willing exchange of actions between individuals. This exchange only takes place if the trustor believes that exploitation is unlikely and as a result is willing to display trust behaviours and to risk vulnerability (Eggers, 2011; Ferres, 2003).

The intentions and actions of an individual must be confidently perceived, while the expectation of ethical treatment should also be present for trust to exist (Eggers, 2011; Ferres, 2003). In order for trust to exist within a leader-follower relationship, it is necessary for a subordinate to observe the following characteristics within a leader: open communication, cooperation, willingness to sacrifice, confidence, predictability and fair treatment (Clapp-Smith et al, 2009; Ferres, 2003). As a result, unbiased processing as well as moral and ethical perspectives can be expected to nurture trust within a leader-follower relationship (Miniotaite, 2012).

Leaders can develop collaborative relationships, build credibility and gain the respect of subordinates when they act authentically, thereby building trusting relationships with subordinates (Avolio et al., 2004). A subordinate's trust stems from judgements of authenticity which are based on consistent leader actions (Coxen et al., 2016). Dirks and Ferrin (2002) suggest that when a subordinate is treated fairly and respectfully, he or she is more likely to display positive attitudes and commitment to a leader.

Studies have suggested that trust plays an important role in the relationship between leadership constructs (e.g. authentic leadership) and follower outcomes (e.g. employee behaviours) (Clapp-Smith et al., 2009; Coxen et al., 2016).

Psychological safety

Both psychological safety and trust involve vulnerability or the perception of risk through choices which seek to minimise negative consequences (Edmondson, Kramer, & Cook, 2004). Psychological safety is conceptualised as an individual's view of the risks and consequences associated with his or her work environment, stemming from a subconscious conviction of how others will respond when an individual finds him/herself in a particular situation (Edmondson et al., 2004; Roussin, 2008). The presence of psychological safety creates confidence in an individual that others will accept and not reprimand his or her actions (Edmondson, 1999).

The difference between psychological safety and trust stems from choice. The trustor's conscious decisions to trust an individual cannot be a choice to feel psychologically safe, but can be a choice to place his or her trust in someone (Edmondson et al., 2004). Psychological safety is thus defined as an individual's perception of the consequences of taking an interpersonal risk in his or her job environment, without the fear of negative consequences to his or her image, status or career (Edmondson & Lei, 2014).

The relationship between a supervisor and subordinate has a direct influence on the feeling of psychological safety that the subordinate experiences within the work environment (Edmondson, 1999; Newman, Donohue, & Eva, 2017). When a supervisor supports rather than controls the subordinate, the subordinate will experience a sense of psychological safety. Such supervisors show a sense of concern for their subordinates' feelings and needs, providing them with positive feedback which not only enables them to develop new skills, but also encourages them to share their opinions without any fear of negative consequences (Edmondson, 1999; Roussin & Webber, 2011).

Employees might be less willing to take risks or express themselves if they perceive these risks to result in negative consequences or even if these risks may lead to embarrassment (Detert & Burris, 2007). Examples of such interpersonal workplace risk include (1) harm resulting from opportunism; (2) identity damage as a result of social interactions and (3) neglect of an individual's interest by others (Williams, 2007). Trust in supervisors can serve to mitigate these interpersonal risks in the workplace, which could result in increased psychological safety (Ning Li & Hoon Tan, 2012).

An increased experience of psychological safety may result in work engagement (Lyu, 2016), as psychological safety reflects upon the belief that an individual can be engaged without any fear of negative consequences (Edmondson, 1999; Eggers, 2011; Roussin & Webber, 2011). Where a work environment displays ambiguity, unpredictability and is threatening, the opposite would be true as subordinates would perceive the environment as being psychologically unsafe. Subordinates working in a perceived psychologically unsafe work environment may disengage from their work and may be reluctant to attempt new things (May, Gilson, & Harter, 2004).

Authentic leaders utilise their own self-awareness as well as the self-awareness of their subordinates to lead (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Displaying an awareness of their own strengths and shortcomings as well as those of their subordinates helps them to lead more transparently. They motivate their subordinates by inspiring them and displaying charisma (Eggers, 2011). Authentic leaders further motivate subordinates by being intellectually stimulating and considerate of subordinates' individuality (Eggers, 2011). Through this, leaders assist their subordinates in developing leadership skills by helping them become more aware of their own feelings, behaviours and thoughts. Leaders and subordinates must be aware of one another's expectations, needs and wants. This leads to positive change in an organisation through developing psychological safety. Psychological safety and trust will lead to transparency, positive self-awareness, a positive moral perspective and a willingness to continually learn (Eggers, 2011).

Work engagement

Work engagement is defined as the 'harnessing of organisational members' selves to their work roles: In engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, emotionally and mentally during role performances' (Kahn, 1990, p. 694). Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter and Taris (2008) describe work engagement as 'a positive, fulfilling and effective motivational state of work-related well-being that is characterised by vigour, dedication and absorption' (p. 187). Vigour refers to increased levels of energy and mental resilience at work, whereas dedication refers to an individual's involvement and fulfilment in his or her work (Bakker et al., 2008). Finally, absorption refers to an individual's happiness and concentration at work which allows time to pass quickly (Schaufeli, Salanova, Gonzales-Roma, & Bakker, 2002).

Engaged employees are energetic and experience a feeling of enthusiasm for their work, and as a result, are completely absorbed by their work to the extent that time flies while working (Bakker et al., 2008; Hassan & Ahmed, 2011). The improvement of work engagement levels in the workforce has become critical for organisational success (Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002; Du Plessis & Boshoff, 2018). This is because work engagement has a positive impact on business, financial and in-role performance, as well as employee productivity (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Du Plessis & Boshoff, 2018).

Various studies suggest that leadership is an important factor that positively contributes to work engagement, either directly or indirectly through other constructs (Coxen et al., 2016; Ebrahim, 2017; Harter et al., 2002; Heyns & Rothmann, 2018). Authentic leaders lead by example - they lead through their values and strive for truthful relationships (Gardner et al., 2005; Kernis, 2003). Leading by example illustrates one's commitment to work and provides guidance to subordinates (Bandura, 1977), allowing subordinates to remain emotionally and physically connected as well as cognitively vigilant in their work roles.

Authentic leadership, trust in supervisors and work engagement

A key element of leadership effectiveness is having trust in supervisors (Coxen et al., 2016). According to Hsieh and Wang (2015), trust in supervisors is linked to favourable organisational outcomes, such as job satisfaction, employee commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour. Studies indicate that trust in supervisors has an indirect effect between the leader's actions and employee behaviours (Coxen et al., 2016; Hsieh & Wang, 2015). When subordinates perceive their supervisors as being trustworthy, it will positively affect their psychological well-being (Lee, 2017). As a result, these subordinates will experience higher levels of work engagement (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). Furthermore, a subordinate's desire to voluntarily return authenticity is increased when the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor to have authenticity. This, in turn, creates an environment of trust and dependency which enables subordinates to be engaged and fully immersed in their work (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). Therefore, trust and employees' attitudes are inextricably linked with leadership being an antecedent.

Authentic leadership, psychological safety and work engagement

Authentic leaders' behaviour stems from their own values and such leaders are driven to display truthfulness and openness in relationships (Gardner et al., 2005; Kernis, 2003). These leaders can be said to lead by example through the demonstration of transparent decision-making (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Supervisors' commitment to their work is displayed when leading by example. This provides subordinates with guidance to become cognitively vigilant as well as emotionally and physically connected with their work performance (Bandura, 1977). According to the research of Kahn (1990), leaders have an influence on the levels of work engagement displayed by subordinates. In a psychologically safe environment, an individual feels accepted and supported as well as able to provide input without any fear of negative consequences or social embarrassment (Kahn, 1990).

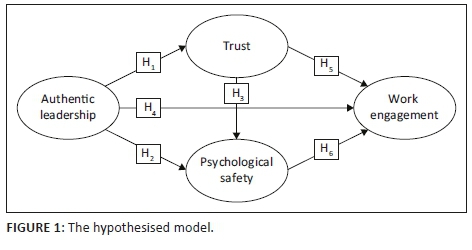

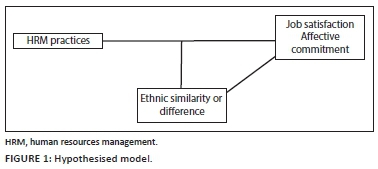

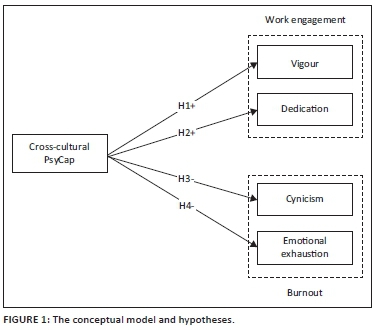

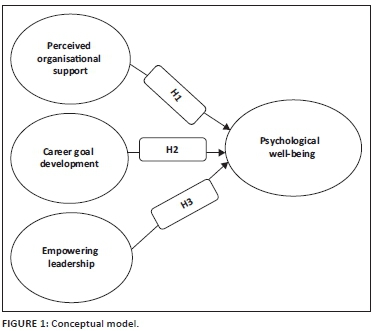

Based on the above discussion, the hypotheses of this study were formulated as follows:

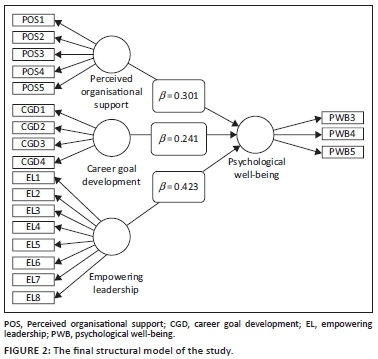

H1: Authentic leadership is a significant predictor of trust in supervisors.

H2: Authentic leadership is a significant predictor of psychological safety.

H3: Authentic leadership has an indirect effect on psychological safety through trust in supervisors.

H4: Authentic leadership is a significant predictor of work engagement.

H5: Authentic leadership has an indirect effect on work engagement through trust in supervisors.

H6: Authentic leadership has an indirect effect on work engagement through psychological safety.

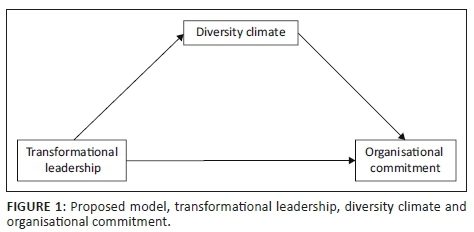

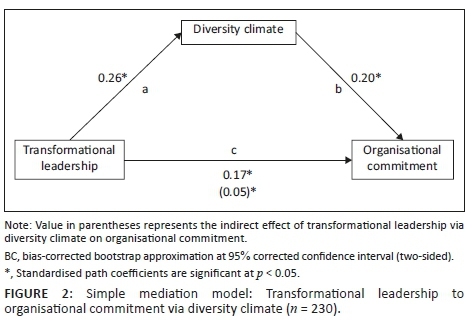

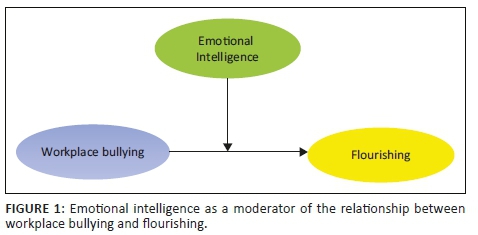

The hypothesised model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Research design

Research approach

This study was quantitative in nature. A cross-sectional survey design was used as the data were collected at one single point in time.

Research method

Research participants

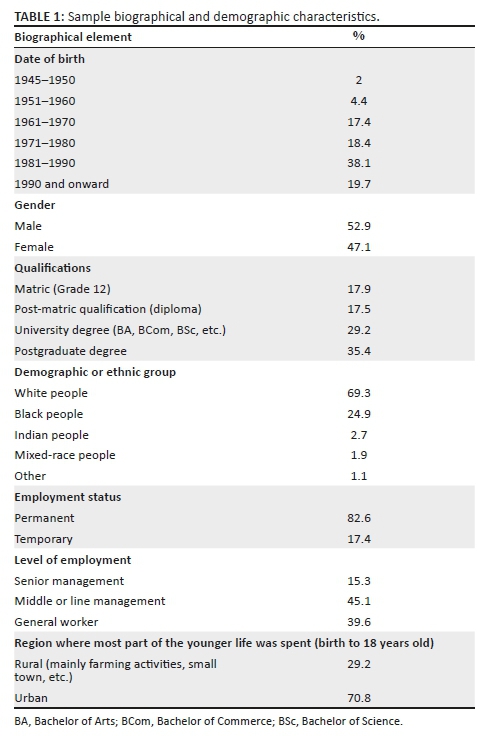

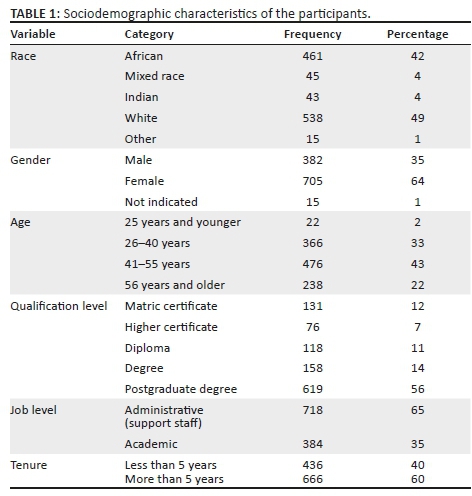

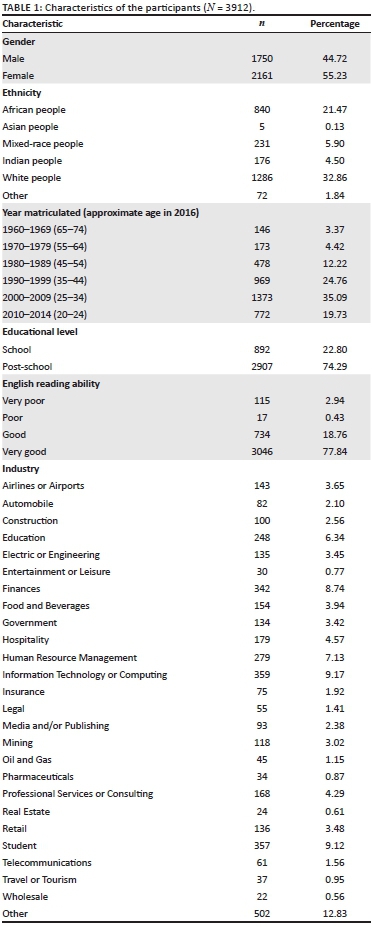

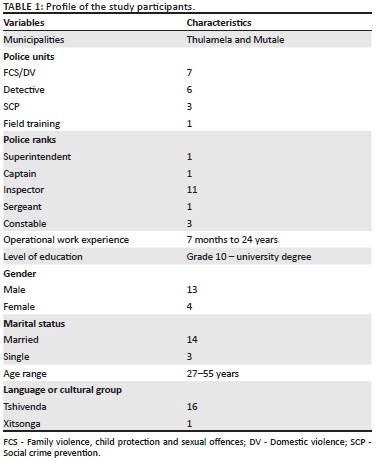

The sample consisted of 244 employees from a South African coal mining company. An availability sampling technique was used because of its convenience and accessibility. Participation in the project was voluntary, anonymous and participants had the right to refuse to participate without consequence. The majority of the sample consisted of males (86.9%) and 54.5% of the sample was African. The most representative home language was Afrikaans (35.7%), followed by Sesotho (29.1%). Thirty-two per cent of the sample fell in the 26-35 years' age group, with 29.9% falling within the 36-45 years' age group. In addition, 50.4% had a grade 12-certificate as highest qualification, while 16.8% received education up until grade 11. Of the participants, 48.8% were employed in the engineering department and a further 23.8% were employed in the operations department. A total of 73.8% of the participants were employed at the C1-C4 level and 14.8% at the B1-B5 level. Years of experience ranged from 1-5 years (28.7%) to 6-10 years (27.9%).

Measuring instruments

Participants completed a biographical questionnaire as well as four measuring instruments to measure authentic leadership, trust in supervisors, psychological safety and work engagement.

Authentic Leadership Inventory (ALI; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011): The ALI consists of 16 items and uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The scale measures the four dimensions of authentic leadership behaviours, namely, self-awareness (four items), balanced processing (four items), moral perspective (four items) and relational transparency (four items). Examples of items include 'My leader describes accurately the way that others view his/her abilities' (self-awareness), 'My leader asks for ideas that challenge his/her beliefs' (balanced processing), 'My leader uses his/her core beliefs to make decisions' (moral perspective) and 'My leader admits mistakes when they occur' (relational transparency). In this study, the ALI showed a composite reliability coefficient of 0.94, indicating acceptable reliability.

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004): The UWES comprises nine items and uses a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). It measures the three dimensions of work engagement, namely, vigour (three items), dedication (three items) and absorption (three items). Examples of items include 'At my job, I feel strong and vigorous' (vigour), 'I find the work I do full of meaning and purpose' (dedication) and 'When I am working, I forget everything else around me' (absorption). The UWES showed acceptable reliability in this study with a composite reliability coefficient of 0.92.

Workplace Trust Survey (WTS; Ferres, 2003): The WTS consists of 36 items, but for the purpose of this study only trust in the immediate supervisor was utilised (nine items). It uses a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An example item is 'I feel that my manager listens to what I have to say'. The trust in the immediate supervisor section of the WTS showed a composite reliability coefficient of 0.94, indicating acceptable reliability.

Psychological Safety Questionnaire (PSQ; Edmondson, 1999): The PSQ contains six items and uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Examples items are: 'Members of the team were able to discuss problems and tough issues openly' and 'Members of the team accepted each other's differences'. The internal consistency of the measure has been acceptable, with a composite reliability coefficient of 0.78.

Statistical analysis

Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2016) was utilised to perform the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (e.g. means, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis) and inferential statistics (e.g. correlations) were used for data analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the factorial validity of the measuring instruments. Raykov's rho coefficients were used to assess the composite reliability of the measuring instruments and a cut-off value of 0.70 was used (Raykov, 2009). Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were used to measure the relationships between the proposed variables. Cohen's effect sizes were used to determine the practical significance of the results, with cut-off values of 0.30 (medium effect) and 0.50 (large effect). A value of 95% (p ≤ 0.05) was set for the confidence interval level for statistical significance.

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the measurement and structural models. The following fit indices were used: chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), standardised root-mean-square residual (SRMR) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Acceptable model fit was indicated by non-significant χ2 values, GFI and CFI (≥0.90) and RMSEA (≤0.08) (Byrne, 2012). The Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayes information criterion (BIC) were used. The smallest value of the AIC and BIC indicates good model fit (Kline, 2011).

To determine whether common method variance (CMV) influenced the results, Harman's single-factor test, a common method, was used. This technique is a post hoc test conducted to determine whether a single factor is responsible for variance in the data (Tehseen, Ramayah, & Sajilan, 2017). This test thus aims to determine the presence or absence of CMV (Tehseen et al., 2017).

The bootstrapping method was used to test for indirect effects. The method was set at 5000 draws (Hayes, 2012) and the bias-corrected confidence level (BC CI) was set at 95%. When zero is not in the 95% CI, one can conclude that the indirect effect is significantly different from zero at p < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

This article adheres to the ethical guidelines for research. Ethical clearance was obtained from the North-West University.

Results

Testing the measurement model

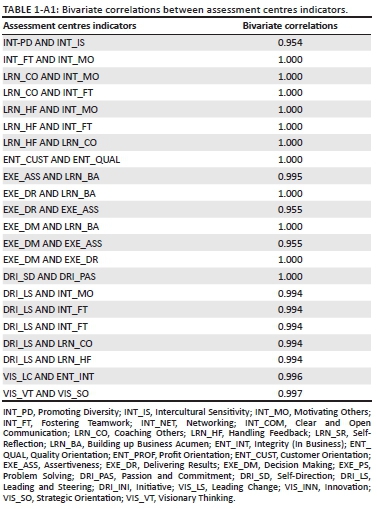

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to estimate the factor structure of the variables. Using SEM, a four-factor measurement model and three alternative models were tested to assess possible relationships between the latent variables.

Model 1 consisted of four first-order latent variables, namely, authentic leadership (measured by 13 observed variables), work engagement (measured by eight observed variables), trust in supervisors (measured by eight observed variables) and psychological safety (measured by three observed variables). All the latent variables were allowed to correlate.

Model 2 consisted of three first-order latent variables, namely, authentic leadership (measured by 13 observed variables), trust in supervisors (measured by eight observed variables) and psychological safety (measured by three observed variables) as well as a second-order latent variable consisting of vigour combined with dedication (measured by six observed variables) and absorption (measured by two observed variables).

Model 3 consisted of three first-order latent variables, namely, work engagement (measured by eight observed variables), trust in supervisors (measured by eight observed variables) and psychological safety (measured by three observed variables) as well as a second-order latent variable of authentic leadership, consisting of self-awareness (measured by three observed variables), relational transparency (measured by three observed variables), balance processing (measured by four observed variables) and moral perspective (measured by three observed variables).

Model 4 consisted of seven first-order latent variables, namely, self-awareness (measured by three observed variables), relational transparency (measured by three observed variables), balanced processing (measured by four observed variables), moral perspective (measured by three observed variables), work engagement (measured by eight observed variables), trust in supervisors (measured by eight observed variables) and psychological safety (measured by three observed variables).

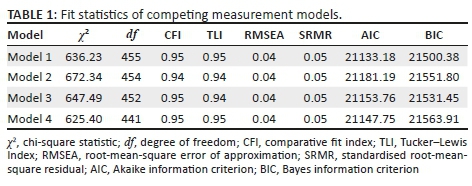

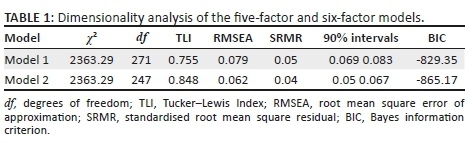

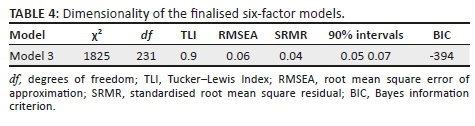

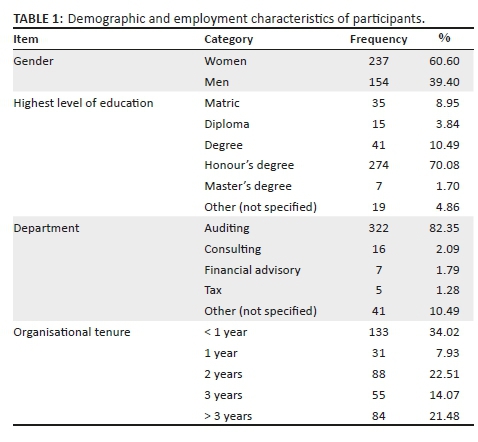

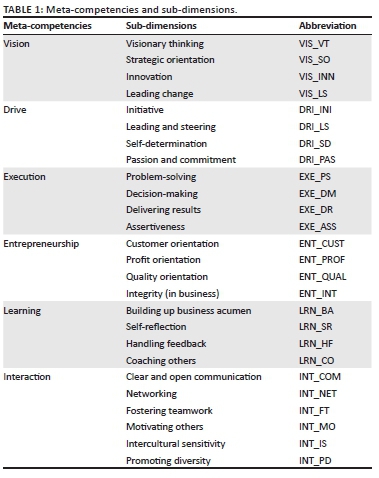

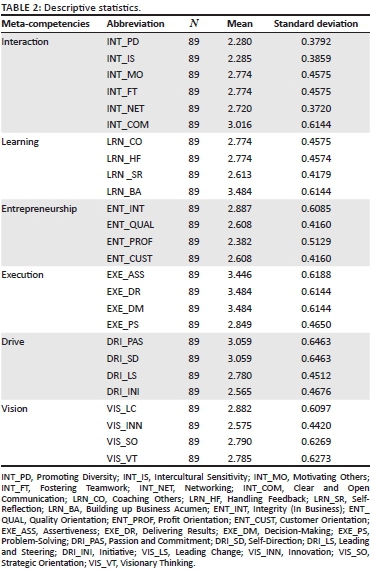

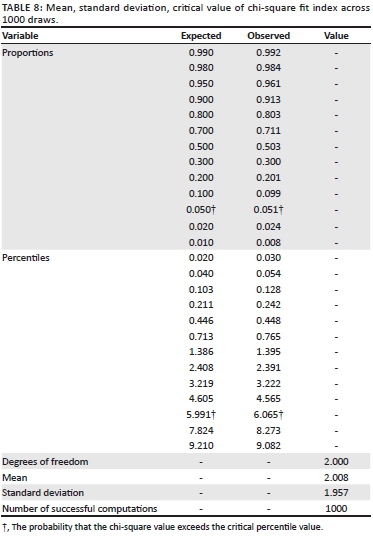

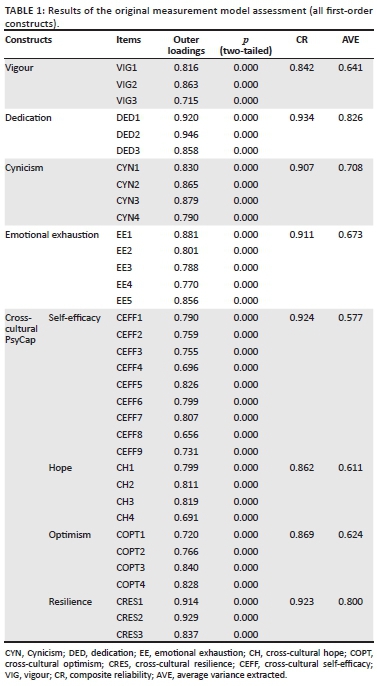

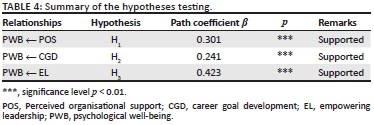

Table 1 presents the fit statistics for the four competing measurement models described above.

Further analyses were conducted in an exploratory mode to improve the fit of the selected model even more. The item errors were allowed to correlate which could improve model fit. According to Byrne (2012), correlated errors could be representative of the respondent's characteristics that reflect bias and social desirability as well as a high degree of overlap in the item content. The revised model (model 1) indicated that the fit improved once the errors were allowed to correlate. A comparison of the AIC and BIC values indicated that model 1 fitted the data the best with a χ2 of 636.23. The fit indices for CFI and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were acceptable (>0.90), as well as the model fit for the RMSEA (<0.05). The SRMR for model 1 was 0.05; values lower than 0.08 indicate an acceptable fit.

Structural model including descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations

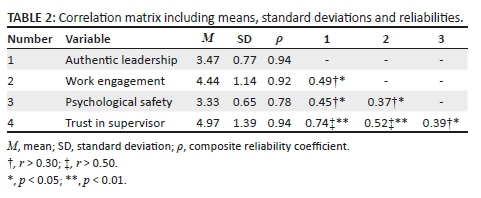

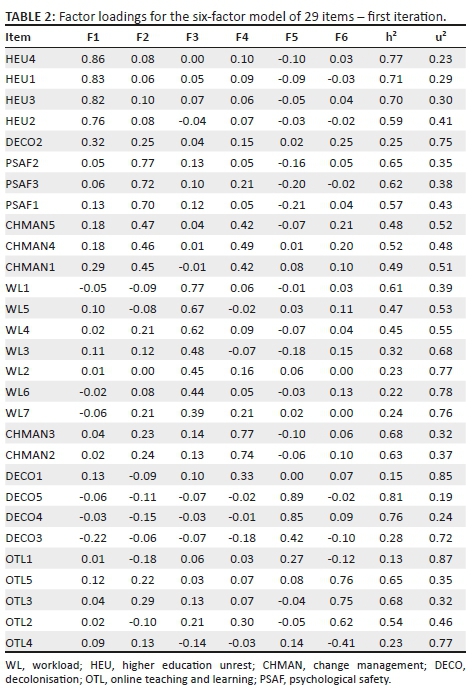

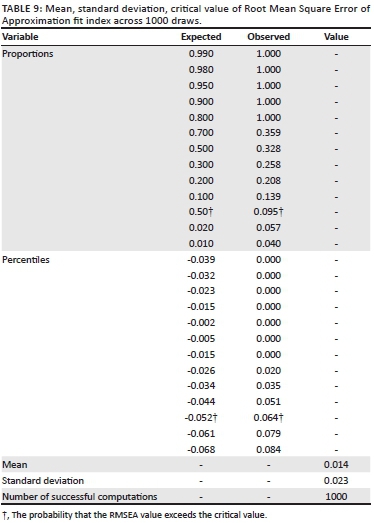

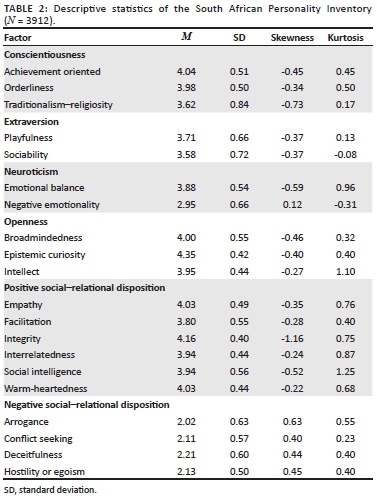

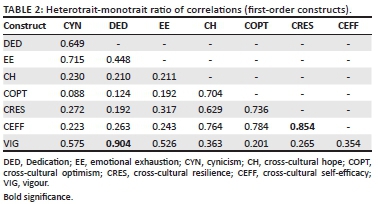

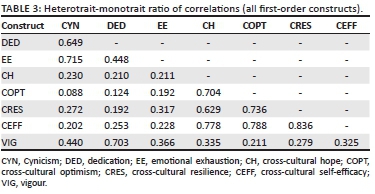

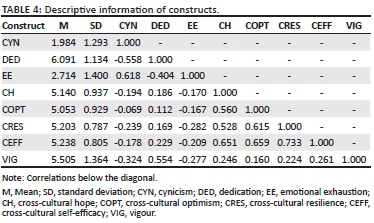

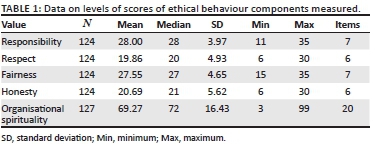

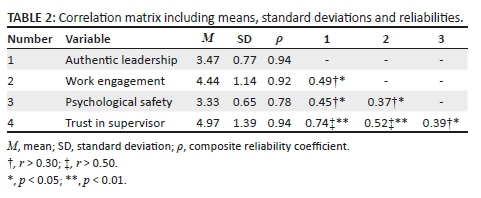

Table 2 contains the descriptive statistics which include the descriptive statistics (e.g. means and standard deviations), Raykov's rho reliability coefficients and a correlation matrix.

As per the results in Table 2, it is evident that the Raykov's rho coefficients of all the measuring instruments were considered acceptable, ranging from 0.70 to 0.94. Raykov's rho coefficients have the same acceptable cut-off points as Cronbach's alpha coefficients, recognising values of ≥0.70 as acceptable (Wang & Wang, 2012).

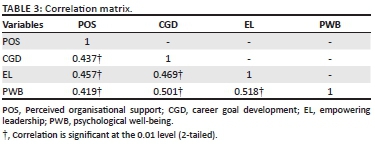

Table 2 further provides the correlation coefficients of the variables which were all statistically significant at either 0.01 or 0.05. Authentic leadership was practically and significantly related to work engagement (r = 0.49) (medium effect); psychological safety (r = 0.45) (medium effect) and trust in supervisors (r = 0.74) (large effect). Work engagement was practically and significantly related to psychological safety (r = 0.37) (medium effect) and trust in supervisors (r = 0.52) (large effect). Trust in supervisors was practically and significantly related to psychological safety (r = 0.39) (medium effect).

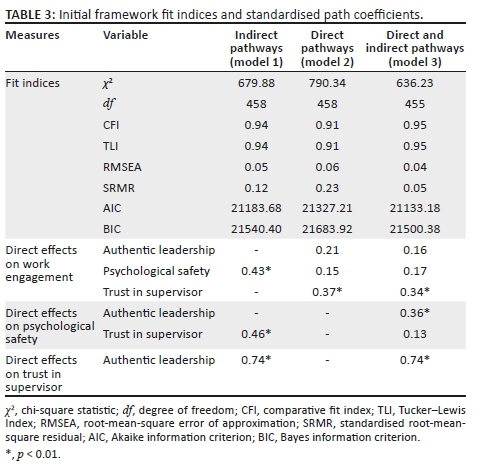

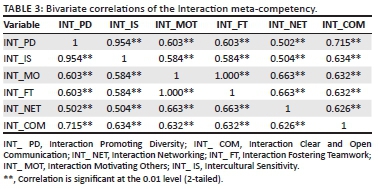

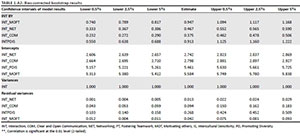

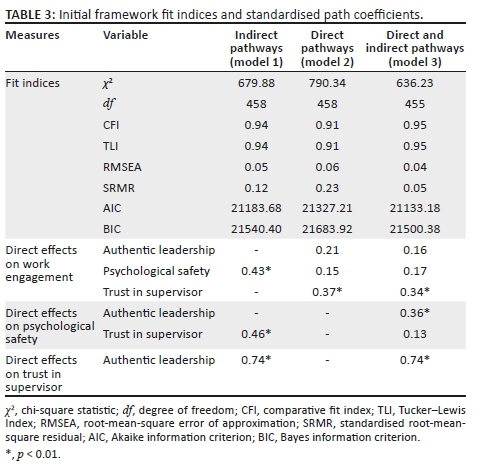

The measurement model formed the basis of the structural model. The hypothesised relationships shown in the model were tested. An acceptable fit of the model to the data was found: χ2 = 636.23, df = 455, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.05 and RMSEA = 0.04. Table 3 shows the fit statistics and path coefficients of the three models.

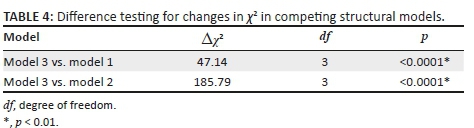

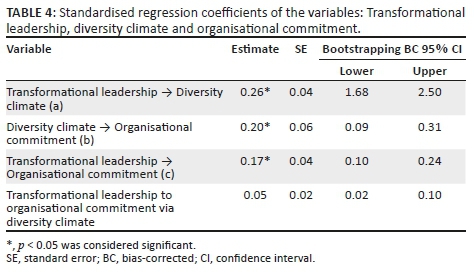

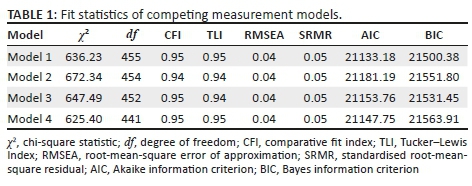

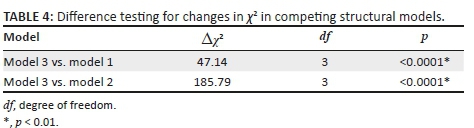

In the above calculations, the maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) estimator was utilised, taking into account the skewness and kurtosis of frequencies. The χ2 values for MLR cannot be directly compared (Satorra & Bentler, 1999). Chi-square difference testing had to be done to determine how the χ2 would change between the different models. Table 4 shows the difference testing for competing structural models. The results in Table 4 indicate that both models 1 and 2 had a significant p -value, which suggests a significantly worse fit than model 3. Therefore, model 3 was the best-fitting model.

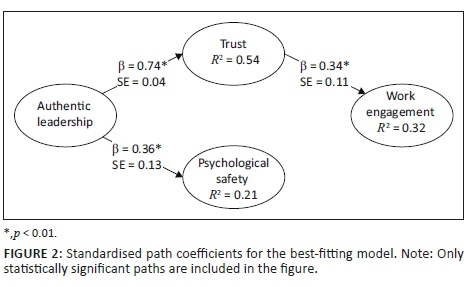

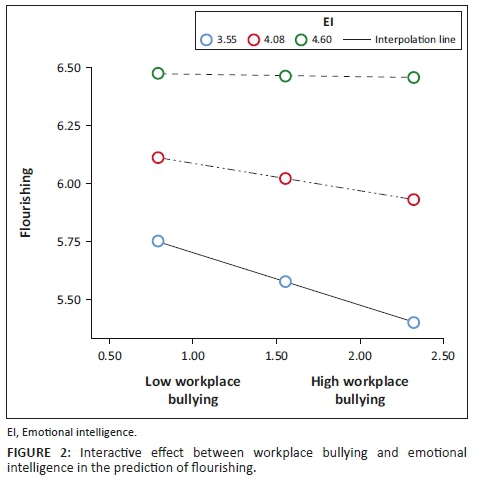

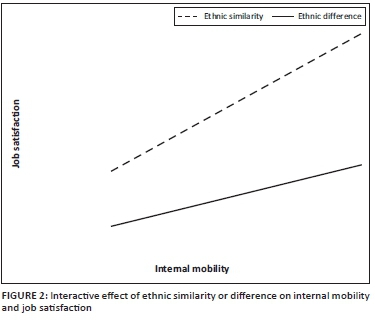

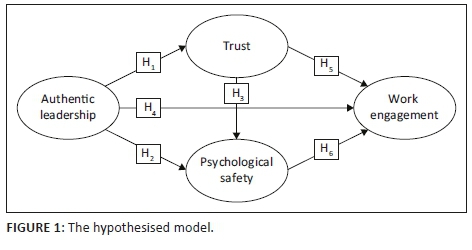

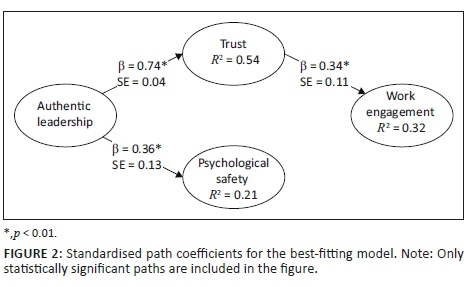

Figure 2 shows the path coefficients estimated by Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2016) for model 3.

From Figure 2, it is evident that authentic leadership is a significant predictor of both trust in supervisors (β = 0.74; p < 0.01) and psychological safety (β = 0.36; p < 0.01). Hypotheses 1 and 2 were therefore accepted. Authentic leadership thus explains 54% of the variance in trust in supervisors and 21% of the variance in psychological safety. Hypothesis 4 was rejected as authentic leadership was not a significant predictor of work engagement (β = 0.16). This is apparent in Table 3.

Based on the results from Harman's single-factor test, the fit statistics of loading the model onto one factor were as follows: χ2 = 1756.65, df = 464, CFI = 0.66, TLI = 0.63, SRMR = 0.11 and RMSEA = 0.11. The fit statistics show that the model did not fit, which indicates that CMV was not a problem (Tehseen et al., 2017). If there was model fit to the one factor, CMV could have posed a problem to the study.

Testing indirect effects

To determine whether indirect effects were present in this study, the procedure, as explained by Hayes (2012), was used. Bootstrapping was used to construct two-sided bias-corrected 95% CIs to evaluate indirect effects.

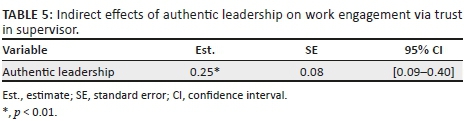

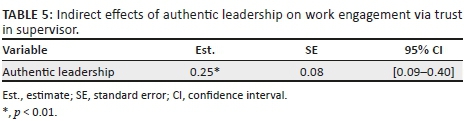

Table 5 shows that the indirect effect of authentic leadership on work engagement through trust in supervisors was significant (p < 0.01) and did not include zero. This suggests that authentic leadership did have an indirect effect on work engagement via trust in supervisors. Based on these results, hypothesis 5 was accepted. Trust in supervisors did not have a statistically significant indirect effect on psychological safety; therefore, hypothesis 3 was rejected. Psychological safety did not have a statistically significant indirect effect on work engagement. Therefore, hypothesis 6 was also rejected. All the hypotheses were thus accepted, except for hypotheses 3, 4 and 6.

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to determine the direct and indirect effects between authentic leadership, trust in supervisors, psychological safety and work engagement. The study was to provide an understanding of how authentic leadership can result in fostering feelings of supervisor trust and psychological safety among employees, resulting in employees being more engaged in their work.

The results indicated that authentic leadership positively influences trust in supervisors. When subordinates perceive authenticity in their leaders, the subordinates will be more inclined to trust those leaders. The results are consistent with previous research which also established that authentic leadership is a positive predictor of supervisor trust (Agote et al., 2015; Coxen et al., 2016; Hassan & Ahmed, 2011). Authentic leaders are regarded by subordinates as transparent, authentic and willing to listen to their ideas (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011). These leaders are also guided by their moral values and are inclined to allow subordinates to take part in decision-making (Walumbwa et al., 2008). Subordinates thus perceive authentic leaders as honest, truthful, reliable and genuine (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Ilies, Morgeson, & Nahrgang, 2005), which contributes to their experience of trust in their supervisor. Leaders who display authentic behaviours in the form of openness and truthfulness thus result in subordinates more readily trusting their intentions (Ilies et al., 2005). These findings are in line with the Leader-Member Exchange Theory (LMX) (Cho & Park, 2011) which regards leadership as a two-way relationship between leaders and followers. In this regard, if leaders display authenticity and transparency, subordinates will reciprocate by trusting the leaders more. A study done in the mining industry in South Africa found the implementation of authentic leadership to be a challenge faced by mines in South Africa (Bezuidenhout & Schultz, 2013). It was found that an environment of trust and openness among employees in this environment was missing because of the lack of effective authentic leadership (Bezuidenhout & Schultz, 2013). It is therefore imperative that mining companies develop authentic leadership within their supervisors to create a climate of trust. This climate of trust will lead to openness and transparency among all employees.

In terms of the impact of authentic leadership on psychological safety, this study found a positive effect between the two constructs. When supervisors engage in authentic leadership behaviours, it leads to a climate of psychological safety among their subordinates. The results are consistent with previous research which also established that authentic leadership is positively related to psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999; Eggers, 2011). The behaviours displayed by a leader are pivotal in promoting psychological safety. Leaders motivate by inspiration, displaying charisma towards their subordinates as well as by being intellectually stimulating and considerate of individuality (Eggers, 2011). Through this, leaders assist their subordinates in developing leadership skills by helping them become more aware of their own feelings, behaviours and thoughts. Leaders and subordinates must be aware of one another's expectations, needs and wants. This leads to positive change within an organisation by developing psychological safety (Eggers, 2011). A platform which allows for continuous communication and participation was identified as a need by employees in the mining industry. These employees felt that they did not have the freedom to express their own ideas and opinions (Bezuidenhout & Schultz, 2013). Authentic leadership would allow mining companies to establish an environment of psychological safety as well as allow employees to freely participate in the organisation.

The results showed that trust in supervisor did not significantly indirectly affect the relationship between authentic leadership and psychological safety. The results of this outcome were unexpected, as a positive indirect effect of authentic leadership on psychological safety via trust in supervisor was expected. According to Eggers (2011), trust between leaders and subordinates is a requirement for the presence of psychological safety. The relationship between the leader and subordinate must be transparent and vulnerable in order for subordinates to experience psychological safety. Leaders who display transparency will create a climate of psychological safety for their subordinates. This, in turn, will promote increased participation by subordinates in the decision-making process as well as foster increased trust in leaders (Eggers, 2011). The unexpected results can perhaps be explained with due consideration to the context of the study. The mining sector is characterised by stringent procedures, rules and regulations - employees thus operate in a structured environment where there is little opportunity for taking risks (Carvalho, 2017). Employees are aware that taking a risk might often result in disciplinary action or, in extreme cases, accidents. The results thus indicate that although employees may trust their supervisors, this does not indirectly affect their feelings of psychological safety.

The results indicated that authentic leadership is not a significant predictor of work engagement. These results also were unexpected, as in theory a positive effect was expected between authentic leadership and work engagement. Authentic leaders display behaviours that are aligned with their own values as well as attempt to achieve truthfulness and openness in their relationships with subordinates (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). They demonstrate transparent decision-making and lead by example, which illustrates their commitment to their work. This serves as a guideline to subordinates to remain physically and emotionally involved in their work and, in so doing, increase the levels of work engagement (Bamford, Wong, & Laschinger, 2013). The impact of authentic leadership and work engagement is also supported by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004) and is consistent with the authentic leadership theory of Avolio et al. (2004). A possible explanation of the results in this study could be that if the organisation's environment limits ownership, then authentic leadership may potentially not prompt work engagement (Mayhew, Ashkanasy, Bramble, & Gardner, 2007). In a former study, the mining industry in South Africa had experienced difficulty with regard to ownership of tasks (Bezuidenhout & Schultz, 2013). The mentioned study found that mining employees were not provided with the opportunity to participate in decision-making or to take responsibility for tasks (Bezuidenhout & Schultz, 2013). Research suggests that employees experience ownership when they are given the opportunity to take control of their job and the work setting (Alok & Israel, 2012). Thus, having an authentic leader does not necessarily mean that employees will be more engaged if they are not afforded the opportunity to take personal ownership of their work tasks (George, 2015). Another study conducted in the South African context among public healthcare employees also found authentic leadership to not be a predictor of work engagement (Ebrahim, 2017).

The findings of this study indicate that authentic leadership had a significant indirect effect on work engagement via trust in supervisor. Authentic leadership has a positive effect on trust in supervisor which, in turn, results in increased work engagement. The results are consistent with a previous South African study which also established that authentic leadership is positively related to work engagement via trust in supervisor (Ebrahim, 2017). In order for a subordinate to perceive a leader as being authentic, a level of trust must be present between the leader and the subordinate (Hassan & Ahmed, 2011). Furthermore, components of authentic leadership such as authentic action and relational transparency are positively related to a subordinate's trust in a leader. Trust between a leader and subordinate also positively predicts employee work engagement (Bamford et al., 2013; Hassan & Ahmed, 2011). When a subordinate has developed a high level of trust in an organisation and its leaders, the subordinate is more likely to become more engaged in his or her work (Bamford et al., 2013; Hassan & Ahmed, 2011). Supervisors who display authentic leadership and lead by example will foster trust within subordinates and encourage subordinates to be more engaged in their work.

In terms of the indirect effect of authentic leadership on work engagement via psychological safety, the results did not confirm the indirect effect. The results of this outcome were unexpected, as a positive indirect effect of authentic leadership on work engagement via psychological safety was expected in theory. According to Kernis (2003), authenticity is related to high levels of work engagement. Kahn (1990) found that work engagement increases in an environment where leaders promote psychological safety, in other words, an environment that allows subordinates to feel supported and accepted as well as able to participate without fear of negative consequences should they fail. Again, if the organisation's environment limits ownership, then authentic leadership may potentially not prompt psychological safety and work engagement (Mayhew et al., 2007). Also, when the environment limits ownership, the subordinates may have perceived this limitation as unsupportive and may have felt constrained - not feeling open to take risks without a fear of the consequences. Therefore, even though psychological safety was present, it may not have had the anticipated effect on work engagement. Supervisors within the mining industry are among the most disempowered of all levels of management as they are caught up in the demands to deliver production (Bloch, 2012). This disempowerment of supervisors would result in a lack of ownership and leave them feeling constrained in their role, thus not inspiring subordinates to remain engaged in their work.

Limitations and recommendations for future studies

This study had several limitations. The first limitation of the study was the use of a cross-sectional design, which restricts the determination of causal relationships among the study variables. The second limitation of the study was the use of the convenience sampling approach which could influence the generalisability of the results obtained. Thirdly, the research was conducted during a time of uncertainty in the mining industry of South Africa, which may be perceived as a limitation. Finally, the research was conducted on a single operation in the mining industry; as a result, generalisation of the findings to other contexts may not be possible.

The following recommendations can be made for future research. Firstly, future research should use longitudinal research designs or diary studies to determine the causal relationships among the study variables. Secondly, future research should expand the study to other organisations and industries as well as other provinces because of the fact that each of these factors may pose its own unique set of challenges and may yield a different result. Thirdly, future research may improve on this study by gathering data from additional sources within organisations, over and above the supervisors and subordinates. Fourthly, future research may improve on this study by utilising a mixed-method approach which includes both quantitative and qualitative data collection. This would allow the researcher to establish the authentic style of the leader as well as the prevailing variables and employee outcomes such as trust and psychological safety. The researcher would then be able to mitigate the close relation between constructs such as trust and psychological safety. Lastly, future research could also include other related leadership constructs into the data collection. This would allow the researcher to determine if the outcomes were exclusively related to authentic leadership, to exclude potential outcomes from other positive leadership constructs such as ethical, transformational, leader-member exchange and empowering leadership.

Implications for management

It is important for employees, leaders and the human resources department to understand the impact of authentic leadership on outcomes such as supervisor trust, psychological safety and work engagement. The lack of ownership, strict rules and regulations, as well as other challenges in the mining sector such as economic uncertainty, may have a likely effect on the leaders' willingness to display authentic behaviours which may have an impact on the feelings of psychological safety, trust and engagement experienced by subordinates. Feeling psychologically safe is important as it decreases 'barriers to engagement' (Wanless, 2016, p. 6). The benefit of having an engaged workforce is enhanced employee performance (Markos & Sridrevi, 2010), which is an important factor in the mining industry.

Trust is an important component of organisational interventions. Therefore, it is vital that employees and the organisation understand that the only way to remain viable is to support one another. When an organisation builds an environment of trust, its employees will reciprocate by becoming more engaged in their work. Both the organisation and employees should participate in a give-and-take relationship. This will help both parties feel confident as well as foster a positive work environment which enhances work performance, psychological safety and work engagement. Authentic leadership plays a key role in creating this positive work environment. Leadership development programmes could be designed in the mining sector to develop authentic leaders who could have a positive impact on the experience of trust, psychological safety and work engagement.

Conclusion

The results of this study emphasise the crucial role of authentic leadership and trust in the supervisor in increasing work engagement. It also highlights the impact that authentic leadership has on psychological safety. Although authentic leadership was not a significant predictor of work engagement, it impacted work engagement indirectly through supervisor trust. These findings indicate that authentic leadership is important for creating trust in supervisors and allowing subordinates to experience psychological safety. It also shows that authentic leadership and trust are important in the development of work engagement.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Author's contributions

N.M. acted as first author (as the article is partially based on her mini-dissertation with M.W.S. as supervisor). M.W.S. and L.C. contributed towards the editing of the article.

References

Agote, L., Aramburu, N., & Lines, R. (2015). Authentic leadership perception, trust in the leader, and followers' emotions in organizational change processes. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 52(1), 35-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886315617531 [ Links ]

Alok, K., & Israel, D. (2012). Authentic leadership and work engagement. The Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(3), 498-510. [ Links ]

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 315-338. https://doi.org/10.bakker1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001 [ Links ]

Avolio, B. J., & Luthans, F. (2006). High impact leader: Moments matter in authentic leadership development. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 801-823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13, 209-223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476 [ Links ]

Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 22, 187-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393649 [ Links ]

Bamford, M., Wong, C. A., & Laschinger, H. (2013). The influence of authentic leadership and areas of worklife on work engagement of registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 21, 529-540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01399.x [ Links ]

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Bezuidenhout, A., & Schultz, C. (2013). A leadership initiative to enhance employee engagement amongst engineers at a gold mining plant in South Africa. Paper presented at the Picmet Conference, San Jose, CA, July 2013. [ Links ]

Bloch, L. (2012). The 4th wave: Culture-based behaviour safety. Retrieved from http://www.saimm.co.za/conference/Pt2012//163-176_Bloch.pdf. [ Links ]

Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Derks, D. (2015). Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(3), 309-325. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2041 [ Links ]

Breytenbach, M. (2017, October). Mining leaders stress the need for good leadership. Retrieved from http://www.miningweekly.com/article/mining-leaders-stress-need-for-good-leadership-2017-10-05. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications and programming. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Caldwell, C., & Dixon, R. D. (2010). Love, forgiveness, and trust: Critical values of the modern leader. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(4), 497-512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0184-z [ Links ]

Carvalho, F. P. (2017). Mining industry and sustainable development: Time for change. Food and Energy Security, 6(2), 61-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.109 [ Links ]

Cho, Y. J., & Park, H. (2011). Exploring the relationships among trust, employee satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Public Management Review, 13(4), 551-573. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.525033 [ Links ]

Clapp-Smith, R., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Avey, J. B. (2009). Authentic leadership and positive psychological capital: The mediating role of trust in the group. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15, 231-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051808326596 [ Links ]

Coxen, L., Van der Vaart, L., & Stander, M. W. (2016). Authentic leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour in the public health care sector: The role of workplace trust. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 42(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip/v42i1.1364 [ Links ]

Deloitte. (2014). Tough choices facing South Africa mining industry. Retrieved from http://www.deloitte.com/assets/…southafrica/…/final_mining_tough_choicesLinks ] Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif" size="2">.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 55, 869-884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183 [ Links ]

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 611-628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611 [ Links ]

Du Plessis, M., & Boshoff, A. B. (2018). Authentic leadership, followership, and psychological capital as antecedents of work engagement. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 28(1), 26-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2018.1438832 [ Links ]

Ebrahim, A. (2017). Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement amongst health care workers (Master's dissertation, North-West University, South Africa). Retrieved from http://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/24948/Ebrahim_AB.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [ Links ]

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999 [ Links ]

Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305 [ Links ]

Edmondson, A. C., Kramer, R. M., & Cook, K. S. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches, 12, 239-272. [ Links ]

Eggers, J. (2011). Psychological safety influences relationship behaviour. Retrieved from http://www.aca.org/research/pdf/researchnotes_fed2011.pdf. [ Links ]

Ferres, N. (2003). The development and validation of the Workplace Trust Survey (WTS): Combining qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Unpublished master's thesis. University of Newcastle, Australia. [ Links ]

Gallup. (2012). Gallup poll on homestyle ethics of professional. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1654/honesty-ethics-professions.aspx. [ Links ]

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. (2005). 'Can you see the real me?' A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 343-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.003 [ Links ]

George, B., Sims, P., Mclean, A. N., & Mayer, D. (2007). Discovering your authentic leadership. Harvard Business Review, 85, 129-138. [ Links ]

George, K. (2015). The relationship between psychological ownership, work engagement and happiness Master's dissertation. University of Pretoria, South Africa. Retrieved from https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/50907/George_Relationship_2015.pdf;sequence=1. [ Links ]

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 268-279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268 [ Links ]^rND^1A01^nRachéle^sPaver^rND^1A01^nSebastiaan^sRothmann^rND^1A01 A02^nAnja^svan den Broeck^rND^1A01 A03^nHans^sde Witte^rND^1A01^nRachéle^sPaver^rND^1A01^nSebastiaan^sRothmann^rND^1A01 A02^nAnja^svan den Broeck^rND^1A01 A03^nHans^sde Witte^rND^1A01^nRachéle^sPaver^rND^1A01^nSebastiaan^sRothmann^rND^1A01 A02^nAnja^svan den Broeck^rND^1A01 A03^nHans^sde Witte

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Labour market interventions to assist the unemployed in two townships in South Africa

Rachéle PaverI; Sebastiaan RothmannI; Anja van den BroeckI, II; Hans de WitteI, III

IOptentia Research Focus Area, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

IIWork and Organization Studies, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

IIIDepartment of Research Group Work Organisational and Personnel Psychology, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Given the absence of organised and accessible information on programmes relating to unemployment in South Africa, it may be difficult for beneficiaries to derive value from existing programmes; and for stakeholders to identify possible gaps in order to direct their initiatives accordingly

RESEARCH PURPOSE: The purpose of this study was to conduct a review of existing employment initiatives within two low-income communities in South Africa, with the aim of identifying possible gaps in better addressing the needs of the unemployed

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY: Unemployment in South Africa does not appear to be the result of a lack of initiatives or a lack of stakeholder involvement, but rather the result of haphazard implementation of interventions. In order to intervene more effectively, addressing the identified gaps, organising and better distribution of information for beneficiaries is suggested.

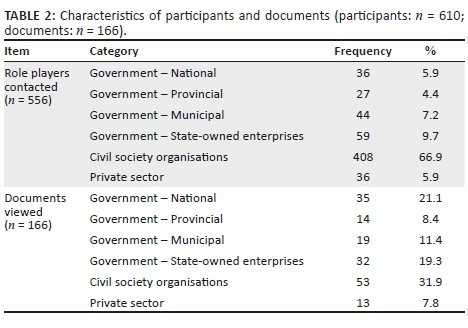

RESEARCH APPROACH, DESIGN AND METHOD: The data were collected via documentary research complemented with structured interviews. Relevant documents (N = 166) and participants (N = 610) were consulted during the data collection phase, using convenience and purposive sampling.

MAIN FINDINGS: A total of 496 unemployment programmes were identified. Most of the interventions were implemented by the government. Vocational training followed by enterprise development and business skills training were the most implemented programmes. Less than 6% of programmes contained psychosocial aspects that are necessary to help the unemployed deal with the psychological consequences of unemployment. Finally, in general, benefactors involved in alleviating unemployment seem unaware of employment initiatives in their communities

PRACTICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS: The compilation of an inventory of employment programmes may be valuable, as it will assist in identifying the most prominent needs of the South African labour market.

CONTRIBUTION OR VALUE-ADD: This study contributes to scientific knowledge regarding the availability of existing unemployment programmes, projects and interventions, and the need for specific interventions.

Keywords: Interventions; unemployment; government; civil society organisations; private sector; township; Gauteng.

Introduction

Unemployment has a detrimental effect on a nation's success, development and prosperity (Feather, 2018; Klehe & Van Hooft, 2018). In South Africa, several role players have started initiatives to deal with the detrimental effects of unemployment. Solely from a government perspective, 27% (ZAR 1.5 trillion) of the annual gross domestic product (GDP) was spent on but a few of the largest, best-funded employment programmes in 2018 (Ramaphosa, 2018). This amount does not include the cost of any other initiatives implemented by the government or other key stakeholders. Yet, despite the major efforts, expenditure and the considerable impact of these interventions, actions seem inadequate as the issue of unemployment remains unresolved and increasingly concerning.

From a report written by the Independent Evaluation Group, it seems that employment programmes in general are somewhat uncoordinated and functioning in isolation (IEG, 2013). Given the absence of organised and accessible information on programmes relating to employment in South Africa, it may be difficult for stakeholders to identify possible gaps in order to direct their initiatives accordingly (National Treasury, 2011). Likewise, beneficiaries may also be unaware of (and may have limited access to) the available resources (Dieltiens, 2015a). Therefore, the problem with employment initiatives in South Africa does not appear to be a lack of initiatives or a lack of stakeholder involvement but rather the haphazard implementation of interventions. As a result, valuable time and money are invested, without a clear indication of the impact thereof (Cloete & De Coning, 2011).

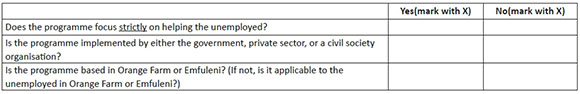

The aim of this study was to identify existing interventions aimed at helping the unemployed in South Africa. A meaningful way to approach the task at hand is to determine the 'who' and 'what' regarding unemployment initiatives by studying current literature and available documentation. Relevant interventions will be clustered according to the involved role players ('who') and the types of programmes that have been implemented within the selected communities ('what'; based on the aim of the intervention).

To date, some inventories of employment initiatives in South Africa have been published (see Centre for Development and Enterprise [CDE], 2008a; Development Bank of Southern Africa [DBSA], 2011; Economic of Regions Learning Network [ERLN], 2015; Graham et al., 2016; International Labour Organisation [ILO], 2012). However, some limitations should be noted. South Africa has undergone substantial economic and social change in the last couple of years. Therefore, reports older than 5 years may be considered obsolete. Furthermore, these reports mainly focus on large-scale interventions, whereas many employability programmes also operate on a smaller scale (Dieltiens, 2015b). Such smaller-scale programmes often deliver more hands-on services, such as providing information about jobs and looking and applying for jobs.

Another noteworthy observation from the above-mentioned documents is that employability programmes are mostly driven from an economic perspective, neglecting the psychosocial aspects of being unemployed (Patel, Noyoo, & Loffell, 2004; Van den Hof, 2015). People generally take up work not only to be compensated (also referred to as a manifest function of employment; Jahoda, 1982) but also to benefit from other latent functions (time structure, social contact, common goals, status or identity and enforced activity) while being employed (Jahoda, 1982). Consequently, when people are (or become) unemployed, it leads to deprivation of both functions, which has been found to negatively impact one's psychological well-being (Jahoda, 1982). By applying interventions that solely focus on easing financial hardship, the psychological aspects, which may contribute to making unemployment bearable, are deliberately left out of the equation, which may result in the unemployed remaining in a state of joblessness.

In general, research regarding programmes aimed at alleviating unemployment within the low-income communities is limited. Identifying existing employment interventions may not only be valuable in recognising the most prominent needs in the labour market but also to promote more focussed action, and make an important contribution to rethink and redesign strategies in addressing employment encounters in South Africa. Based on the above statement of the research problem, the main aim of this study was to make an inventory of employment interventions in two South African townships. The specific objectives were:

-

to determine the primary stakeholders involved in addressing unemployment in the involved communities

-

to develop a framework to classify active labour market programmes

-

to identify labour market programmes in Orange Farm and Emfuleni, implemented by included stakeholders, according to the framework, as a means of relieving unemployment; and

-

to make recommendations for future research and practice.

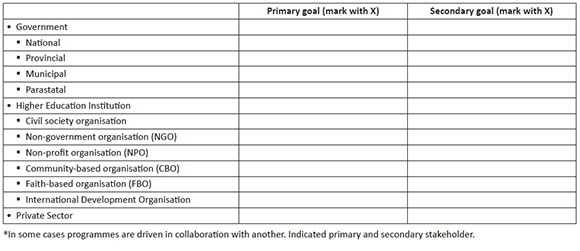

Role players

Intervening to promote employment is regarded as a major challenge (IEG, 2013). Consequently, different role players execute initiatives. Organisations such as trade unions, banks, economic development agencies, universities and research entities have been found to be involved in addressing the issue of unemployment. While all the role players make valuable contributions, reports documenting labour market interventions consider the main role players to be the government, civil society organisations (CSOs - including international development organisations) and the private sector (CDE, 2008a; IEG, 2013; Mayer et al., 2011; National Treasury, 2011). Therefore, we elaborate on these role players next.

South African government

Definition: Government is described as the people who have the authority to govern a country (Oxford Dictionary, 2017). Form: The South African government consists of three spheres, namely, national, provincial and municipal (local), as well as state-owned enterprises (SOE; Republic of South Africa, 1996). Regulated by: According to South Africa's latest macro policy, the New Growth Path, it aims to develop effective strategies to reduce poverty, inequality and unemployment, by means of making job creation the focal point of the policy. The government aims to create a million jobs by involving role players such as the private sector and trade unions (National Treasury, 2011). Contribution to unemployment: As a means of achieving the desired goals, the national government has implemented several job creation programmes, such as the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP; Department of Public Works, 2009), the Community Work Programme (CWP) (Department of Cooperative Governance, 2011) and the Jobs Fund (CDE, 2016). Concurrent with the national policies and initiatives, both provincial and municipal governments have implemented numerous programmes and centres providing services such as skills training and entrepreneurship development, job placement services, career guidance and workplace readiness services. During the literature review, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) were also identified as a role player. As both Orange Farm and Boipatong are located close to five relatively large institutions, who are all actively involved in community projects, HEIs seemed important to consider. Higher Education Institutions are classified as a SOE, and were therefore included as government initiatives.

Civil society organisations

Definition: Civil society organisations can be defined as non-government organisations mainly established to help vulnerable interest groups (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] and United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2014). Form: CSOs come in various forms, such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), community-based organisations (CBOs) and faith-based organisations (FBOs). Because of the similar humanitarian nature, International Development Organisations have also been classified under this category. Regulated by: Although somewhat regulated by codes, such as the Non-Profit Organisations Act of 1997 (Non-Profit Organisations Act, 1997), these acts are unrelated to and have no impact on the purpose of CSOs' existence. Therefore, because of the voluntary, humanitarian nature of CSOs and international development organisations, they are under no obligation to perform certain duties. Contribution to unemployment: CSOs invest a great deal in the development of communities, which often include services for the unemployed, such as job training programmes, vocational rehabilitation, vocational counselling and guidance (Chitiga-Mabugu et al., 2013). Similar to CSOs, the purpose of international development organisations is to provide support to developing countries, by means of financial aid, usually aimed at human development, sustainability and alleviating poverty in the long term (Venter, 2015).

Private sector

Definition: The private sector refers to that part of an economy that is not ruled or owned by the government (Merriam-Webster, 2017). Form: The private sector comprises the Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise sector (SMMEs) and larger corporate enterprises. Regulated by: Labour market legislation such as the Employment Equity Act and the rise of Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment regulations, although initiated by the government, may impact private sector involvement. Furthermore, organisations may also become involved in community projects for the sake of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reputation. However, according to the South African Companies Act, South African organisations do not have a legal obligation to engage in CSR projects (South African Companies Act, 61 of 1973). Contribution to unemployment: There are various ways in which the private sector can contribute to the plight of unemployment. Firstly, it contributes funds for skills development and workplace training through the Skills Development Levy (Skills Development Act, 1998). Secondly, it employs workers and claims a tax allowance through recognised learnership and apprenticeship programmes (Levinsohn, Rankin, Roberts, & Schöer, 2014). These initiatives are essentially government initiatives; therefore, except for their involvement in these government initiatives and the odd CSR project, the private sector's participation in unemployment initiatives seems minimal and heavily underutilised (ILO, 2012).

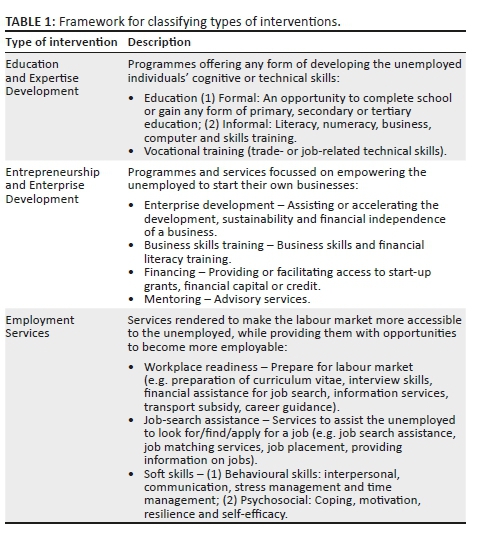

Development of labour market intervention framework

There are different ways of categorising employment interventions. One of the objectives of the current study was to create a framework according to which the different types of employment interventions can be categorised.

Much of the available literature on labour market programmes distinguishes between 'active' and 'passive' labour market policies (see Kluve et al., 2016). Passive labour market policies are described by the ILO as generosity policies that replace labour income (ILO, 2010). Unlike other countries that offer unemployment grants, South Africa only has one such policy, the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF), which provides temporary relief to those who are financially distressed owing to losing their job (Bhorat, Goga, & Tseng, 2013). Whereas active labour market policies are strategies that emphasise labour market (re)integration, these policies focus on reducing unemployment by creating and improving employment opportunities and increasing the employability of the unemployed (National Treasury, 2011).

Furthermore, active labour market policies are often subdivided into labour 'demand' and 'supply' side. Demand-side initiatives are crucial in influencing economic growth, as they are primarily designed to create decent jobs and to incentivise the private sector by means of subsidies to create employment and training opportunities for the unemployed who are also inexperienced. It generally lies within the governments' responsibilities to manage and implement such macroeconomic policies (Altman & Potgieter-Gqubule, 2009; Ernst & Berg, 2009). The South African government has implemented a few programmes (e.g. EPWP, National Treasury's Jobs Fund and the youth wage subsidies) to serve as demand-side policy measures (Altman & Potgieter-Gqubule, 2009). Given the fact that South Africa has only one passive labour market policy, and limited demand-side interventions, covering only a narrow scope of this study, it was omitted from the study. Most government interventions have been directed at the supply side (initiatives promoting and enhancing the employability of the unemployed; Levinsohn et al., 2014). Therefore, the emphasis of the study was mainly on active labour market policies focussing on supply-side interventions.

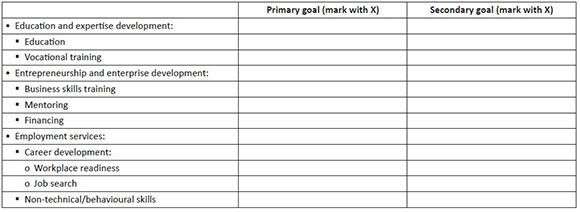

Quite a number of studies have been conducted as a means of compiling a comprehensive list of supply-side employment interventions (Betcherman, Godfrey, Puerto, Rother, & Stavreska, 2007; Bertrand et al., 2013; Burchell, Coutts, Hall, & Pye, 2015; Cho & Honorati, 2014; Cunningham, Sanchez-Puerta, & Wuermli, 2010; Dar & Tzannatos, 1999; Kluve, 2014; Kluve et al., 2014, 2016). However, within the South African context, these inventories are somewhat more limited (see CDE, 2008a; Development Bank of Southern Africa, 2011; Economic of Regions Learning Network, 2015; ILO, 2012). Based on both national and international literature, broad corresponding themes were identified. In most studies, three broad themes were noted: skills development programmes, business development opportunities and a variety of employment services.

According to the Economic of Regions Learning Network (2015), education and vocational training are crucial requirements to facilitate entry into employment (ERLN, 2015). Because many young people drop out of mainstream education, finding employment may be especially challenging (ERLN, 2015). One approach to enhancing their employability may be programmes that focus on education (Kluve et al., 2014). These programmes can be divided into formal and informal programmes. Generally, formal programme opportunities are offered to gain a formal education (also referred to as 'second-chance programmes'), whereas informal programmes are designed to teach basic skills and/or cognitive abilities, specifically for school dropouts (e.g. literacy and numeracy programme; Betcherman et al., 2007; Dar & Tzannatos, 1999; Development Bank of Southern Africa, 2011; ILO, 2011). Another approach linking with education seems to be vocational training programmes. These programmes are generally aimed at equipping the unemployed with the necessary trade- or job-specific vocational skills and/or practical work (e.g. internships, on-the-job training, and apprenticeships; Kluve et al., 2014). The first broad category was therefore identified as education and expertise development, comprising education and vocational training.

Another much required skill, particularly within the South African context, where job opportunities are limited, is entrepreneurship (CDE, 2008a). Entrepreneurship programmes cover a broad variety of skills aimed at empowering the unemployed to successfully establish and manage their own businesses (Kluve et al., 2014). These skills range from basic training on enterprise development (business plan writing and development) to business skills development (such as basic finance, marketing, sales and management programmes; Puerto, 2007). Programmes focussing on enterprise development may include financial support services (such as start-up loans or information regarding finance opportunities), mentoring and consultation services from experienced entrepreneurs. The second broad category was identified as entrepreneurship and enterprise development and consists of enterprise development, business skills training, financing and mentoring programmes.

Lastly, it seems that certain non-cognitive skills are required to deal with the challenges of the modern labour market. Although these skills are increasingly demanded by employers, it is surprising that some inventories overlook programmes that are not strictly focussed on labour market activities (lessening economic hardship; see CDE, 2008a; Cho & Honorati, 2014; Dar & Tzannatos, 1999; Economic of Regions Learning Network, 2015; Godfrey, 2003; Grimm, 2016; Grimm & Paffhausen, 2014; Holden, 2013; IEG, 2013; ILO, 2012). Fortunately, other inventories regard initiatives aimed at increasing participants' non-cognitive skills, such as soft skills, life skills and behavioural skills, as important aspects for gaining employment (see Bertrand et al., 2013; Cunningham et al., 2010; Economic of Regions Learning Network, 2015; Goldin, Hobson, Glick, Lundberg, & Puerto, 2015; Kluve, Lehmann, & Schmidt, 2008; Kluve et al., 2014, 2016; Mayer et al., 2011; Puerto, 2007). A distinction is often made between services aimed at preparing the unemployed for the workplace, helping them to look for a job and teaching them necessary, non-technical, soft skills (e.g. interpersonal, time management and problem-solving skills). The last category was therefore labelled employment services and consists of workplace readiness, job-search assistance and soft skills development programmes.