Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Child Health

On-line version ISSN 1999-7671

Print version ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.15 n.2 Pretoria Jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajch.2021.v15.i2.1766

RESEARCH

Kangaroo mother care: Lived experiences of mothers in three hospitals of Limpopo Province, South Africa

N D NdouI; T M MulaudziII; R A AnokwuruI; A H Mavhandu-MudzusiIII

IPhD; Department of Advanced Nursing Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, Limpopo, South Africa

IIMSN; Department of Advanced Nursing Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, Limpopo, South Africa

IIIPhD; Department of Health Studies, University of South Africa, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is a low-expense, highly effective management plan for preterm babies in low-to middle-income countries. Limpopo Province initiated KMC as part of the Limpopo Initiative for New-born Care in their district hospitals. We explored the experiences of mothers during KMC in the hospitals in Vhembe District

OBJECTIVE: To document lived-in experiences of mothers providing KMC in Vhembe District of Limpopo Province, South Africa

METHODS: Using a phenomenological design, 13 mothers who provided KMC were interviewed from the three hospitals in the Vhembe District. Following a phenomenological analysis of each transcript, three main themes emerged. All relevant ethical protocols were observed during the research

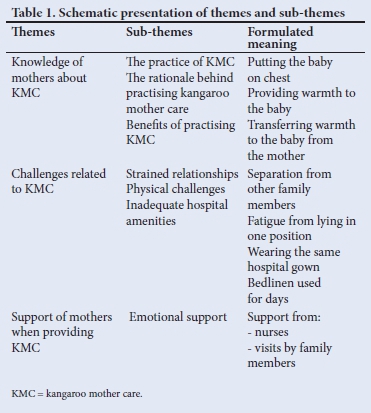

RESULTS: The mothers' experience was characterised by three main themes and nine sub-themes. The mothers understood the practice, rationale and benefits of KMC. Despite this knowledge, mothers reported challenges: strained family relationships, fatigue associated with the practice of KMC, inadequate hospital amenities, and ineffective instrumental support and disruption of academic progress for the student mothers. Mothers received emotional support from their relatives, spouses and professional nurses

CONCLUSION: This is the first known study to report on the shortage of amenities regarding KMC. It is important for the Limpopo Department of Health to improve the provision of basic amenities in the unit to sustain the objectives of the Limpopo Initiative for New-born Care

Preterm birth is a global health burden that accounts for the death of one million preterm neonates every year,[1] of which about 78.9% occurs in Africa.[2,3] Inadequate resources, improper care and delay in prompt care are the leading causes of complications and deaths in preterm neonates.[3,4]

The implementation of kangaroo mother care (KMC) as an alternative or as supplementary care to incubation of the preterm revealed reduced mortality and morbidity in preterm neonates.[1,4] It entails prolonged skin-to-skin (STS) contact between mother and infant, exclusive breastfeeding whenever possible, early discharge with adequate follow-up and support, and initiation of the practice in the facility and continuation at home.[5-7] Adapting to life is difficult for preterm babies because of immature body systems. Preterm babies create stressful situations and a feeling of inadequacy in their mothers. Mothers who practise KMC exhibit less stress and demonstrate confidence in parenting preterm babies.[8]

In addition, the warmth of STS contact of mother and baby helps thermal regulation of preterm babies. The exclusive breastfeeding component of the KMC promotes bonding between mother and baby. Overall evidence of the practice of KMC shows a reduction in neonatal mortality caused by complications of a preterm birth.[6,9,10]

Though researchers have established the benefits of KMC, they have also shown that there are enablers and barriers to the actual practice of KMC. Factors enhancing or preventing the success of KMC are the same, and include governmental support, acceptance by health practitioners, good training on KMC, and financial support.[1,9]

Background

The Perinatal Problem Identification programme in South Africa (SA) identifies complications from preterm birth as one of the leading causes of neonatal death. Complications account for 44% of neonatal mortality.[11] In response to this report, 18 initiatives were rolled out in 2008 to reduce the neonatal mortality rate, and are still in place today.[11] Scaling up of KMC is one of the strategies in these initiatives to combat neonatal mortality.[12,13] Each of the nine provinces in SA developed programmes to implement these initiatives. Limpopo Province created the Limpopo Initiative for New-born Care (LINC) in 2003. One of the components of this initiative is the integration of a dedicated KMC unit with neonatal care. Each KMC unit is equipped with basic amenities for mother and baby. Professional nurses train and monitor mothers in the practice of KMC in the unit.[14] This initiative generated data used in developing national interventions to combat neonatal mortality.

In Limpopo Province, however, there are no reports on the experiences of mothers providing KMC. The researchers of the present article believe that a report on mothers' experiences will enhance nurses' understanding of the perceptions of mothers on KMC. In turn, the quality of care given by nurses to mothers will improve.

Objective

The purpose of this research article is to document lived-in experiences of mothers providing KMC in Vhembe District of Limpopo Province, SA. The researchers obtained ethical clearance from the University of Venda's Higher Degree Committee, Limpopo Provincial Health Department, Vhembe District health office and the respective Vhembe district hospitals.

Method

Research design

The study was underpinned in a phenomenological approach to understand the experiences of mothers providing KMC in Vhembe District hospitals. Phenomenology is the thorough, systematic study of human experience that aims to produce insightful descriptions of the way people experience their world.[14]

Research questions

What are mothers' lived experiences of providing KMC? What type of support do mothers receive when providing KMC?

Recruitment and consent

Thirteen participants who met the inclusive criteria were purposively selected from the four Vhembe district hospitals with KMC units in the Vhembe District. One of the researchers (who is the primary researcher) explained the purpose and details of the research to the participants. Each participant signed informed consent forms after thorough explanation of the aim and their ethical right and willingness to participate in the research.

Population

The population comprised all mothers who gave birth to premature babies at the selected hospitals, who were providing KMC and who met the sampling criteria. The target population comprised mothers who were providing KMC from day five until discharge. The accessible population comprised mothers who provided KMC in a KMC unit at the time of interviews and who were willing to sign informed consent forms.

Thirteen participants with various occupations were interviewed. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 42 years. Ten were married and three were single. Their educational status ranged from grade 7 to a degree.

Data collection

The primary researcher met with participants prior to the day of the interview to ascertain a time for the interview. Each in-depth face-to-face interview took 45 - 60 minutes in a well-lit, quiet, private room next to the KMC unit at each hospital. Interviews were audio recorded. The researcher elicited better responses using probing questions such as: 'Tell me more about the challenges you are experiencing, and your experiences in your relationship with nurses and family members.' Data were collected over a period of three months from 1 July to 30 September 2017. An in-depth individual interview was used to obtain data from participants in a suitable language, which was either Tshivenda or English.

Data analysis

Data were transcribed verbatim and translated from Tshivenda language into English by an expert. The researchers (midwives and midwifery lecturers) were able to distance their biases and knowledge about KMC through bracketing.[15] Each transcript was read so as to identify significant statements and their meaning (horizontalisation).[16] Following horizontalisation of each transcript, significant statements were then collapsed into categories based on their relationships and similarities. These categories were further collapsed into themes according to careful textual and structural meaning of the categories. Each researcher examined the categories and the themes to ensure trustworthiness of the research.

Results

Four themes shown in the table below (Table 1) emerged from the analysed data obtained from mothers who were providing KMC. They include knowledge of mothers about KMC, challenges of providing KMC, mothers' relationships with nurses and family members, and support of the mothers.

Knowledge of mothers about KMC

The findings of the study revealed that mothers had knowledge of practising KMC. They understood the position of babies on the chest and the benefits of KMC to the baby.

'Kangaroo Mother Care is when I put the baby here [pointing to the chest] and provide warmth to the babies, making sure that the child is not affected by cold at all. If I give warmth to the child, the weight will be normally increased.' (P.3)

'When I provide Kangaro o Mother Care, warmth will be transferred from my skin to my baby skin. When I provide Kangaroo Mother Care, I normally put the baby between the breasts who is wearing only a diaper. The main idea is to make the child grow through the warmth from the mother's warmth.' (P.8)

The participants affirmed that KMC afforded them the opportunity to be close to their babies all the time and monitor the wellbeing of the babies.

'I constantly observe my baby for the breathing patterns and body temperature and how she sucks from the breast. All the time when she cries, I am closer to her.' (P.13)

Challenges related to KMC

Participants from the study highlighted the challenges they encountered while practising KMC. One of the major challenges is separation from family members during the hospital stay, which creates a gap in the care of other family members.

'Eish! I left my daughter with her father. Ever since I came to the hospital, I never went home. My 8-year-old child says she is bored since others are with their mothers, while she is not. The last time I spoke to her, she said I should come back home. This situation is frustrating me because the father gets to work by 03h30 in the morning. She remains alone at home when the father goes to work, and no one wakes her up for school.' (P.9)

A prolonged hospital stay causes strain in husband-and-wife relationships.

'My husband is not happy about this situation which makes me to be away from home. I got this over the phone through my conversation with him because he is not staying with me at home. He is staying far away from us. Another thing is that since the babies were born, I did not go home and it is true he did not take that well. Another thing, I have left my eldest child with the father.' (P.7)

Participants also experienced fatigue owing to the position maintained during KMC and complained of backache and fatigue. ''I feel tired on my vertebral column as if I had been carrying a heavy load on my back, but my focus is on helping my babies to grow. My time to relax will come when my babies gain the expected weight.' (P.5)

'It is painful to spend most of the time lying on your back in the evening. I move from bed to chair and move around like that.' (P.1)

In the KMC unit, mothers have basic amenities to make their stay in the hospital comfortable. Unfortunately, participants complained of inadequate amenities in the unit.

'One may give birth today, sleep over with the same dress and it may not be easy for me to walk around using the very same dress. I spent three days wearing the same dress but have identified a nightdress put off by someone, I took it and washed it with warm water.' (P.8)

The inadequate amenities encourage dirtiness. To avoid this, participants wash their clothes with their own detergents. Washing clothes was also done to avoid bad odour from clothes soiled with breastmilk.

'Some of the mothers do not wash hospital night dresses because they do not have a powder. You may find a woman sometimes wearing a dress drenched in breastfeeding milk and it smells bad. It compels one to change the dress twice a day. I wash one and wear the other one. Family members bring packets of washing powders from home.' (P.9)

Participants stated that there were days on which they were not supplied with diapers for the babies. Mothers were compelled to buy diapers and they ended up sharing with those who could not afford them. Support of mothers during KMC differs in accordance with nurses' understanding of the woman's situation.

'Nurses informed us that there are no diapers. Last week, one of the mothers of twin premature babies did not receive visitors and there was no supply of diapers from the nurses and we had to donate at least two diapers each to her.' (P.4)

One of the participants complained about the effects of the long hospital stay on her studies.

'When the baby was born prematurely, I was still attending the school lessons, but now I can no longer get back because the baby is underweight, and I don't know when he will be discharged.' (P.10)

Support of mothers during KMC

Nurses play a fundamental role in the KMC unit. They assist mothers with necessary information as well as basic amenities. Our findings revealed the support of nurses to participants in the KMC unit. 'The nurses treat us so well because they even demonstrate to us how to handle the premature babies. The babies have to be breastfed always. One more thing is that they tell us not to put a baby on the bed as it is only for the mother. Instead, the baby has to be always kept between the breasts.' (P.10)

'If you need clarity on something concerning the baby, they help us.' (P.6)

In addition to the care that participants receive from nurses, they receive supplementary support from family members who visit the hospital.

'Family members pay me a visit and comfort me, telling me not to worry or to think too deep about the disadvantages of this situation as it may negatively affect production of breast milk.' (P.7)

'My husband visits me frequently and he has accepted the situation caused by giving birth to a premature baby and of staying long in the hospital. He always says that he wishes that the baby to comes home soon. Even the grandmother of the child has accepted it.' (P.1)

'From relatives, I am getting a great support, they often come to pay a visit all the time.' (P.4)

Discussion

The aim of the present study is to describe the lived experience of mothers who provide KMC in the district hospitals in Vhembe District of Limpopo Province. KMC is one of the initiatives of the LINC. Adequate and correct knowledge is crucial to practice in public health. Some studies have shown that mothers demonstrate adequate knowledge on KMC while others showed poor knowledge. The findings of our study revealed that mothers demonstrated adequate knowledge of KMC; this is important as insufficient knowledge or no knowledge at all will be detrimental to the provision of KMC by the mother. Provision of KMC in the right way is crucial to successful outcomes. Constant closeness to babies is one of the benefits emphasised by mothers to be a motivation for providing KMC.[7] Mothers need to constantly put the naked babies on their chest to provide warmth. This position also creates a bond and closeness that mothers appreciate. The mothers in our study reported this bond as one of the benefits of providing KMC to their babies. This finding is similar to reports in many studies.[5,6,10]

The practice of KMC has been shown to reduce neonatal death and increase bonding between mother and baby. However, the extended hospital stay related to mothers in KMC units put strain on family care and relationships with other children;[17] this contrasts with the shorter hospital stays reported in the literature brought about through provision of KMC at home.[18,19] Mothers in the study complained of fatigue caused by retaining the one position of holding babies between their breasts. Fatigue is one of the disadvantages reported in studies on KMC.[20-22]

Findings in the study also revealed a lack of basic amenities in KMC units as one of the challenges that mothers experienced.

According to the LINC, KMC units are equipped with basic amenities. A lack of basic amenities becomes a barrier to the practice of KMC.[9] A study in Tanzania showed a lack of amenities to support KMC in hospital.[22] Another study also listed inadequate amenities in the hospital as one of the barriers to KMC.[23]

Seidman et al.[1]and Chan et al.[9]established that support from health practitioners and relatives was very important as mothers were not able to perform their responsibilities. Support of mothers during KMC is crucial to the success of KMC practice. Mothers in our study reported receiving support from midwives and their relatives. A study from Pakistan showed that support from relatives enhanced the practice of KMC in home settings.[24] Though our study was of KMC practised in the hospital setting, support from relatives in terms of taking care of affairs at home and visiting the hospital was crucial to success of KMC. This type of support reduces anxiety of mothers about homecare. Another study in Tanzania showed lack of support from healthcare workers and listed it as one of the barriers to success of KMC.[22]

Study strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of the present study is that mothers were interviewed from three different hospitals in Vhembe District, which afforded participants a chance to learn more about KMC. A limitation to the study is the possibility of bias owing to the method of selection. Mothers in the study were those who showed interest and were available at the time of interviews.

Conclusion

The present study described the experiences of women providing KMC to their preterm babies. The mothers expressed their knowledge of KMC and their challenges. Our study documents the experiences of mothers in Limpopo Province since the LINC in 2003. This point has an implication in informing policy on KMC. One of the important findings in the study was lack of amenities in the unit. Therefore, it is important for the Limpopo government to improve the provision of basic needed amenities in each unit to improve the facilities. In addition, routine periodic inspections should be carried out to maintain standards in each unit.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgments. None.

Author contributions. Study design: TMM, NDN, AHM. Data collection: TMM, NDN. Data analysis: TMM, NDN, RAA, AHM. Study supervision: NDN. Manuscript writing: NDN, RAA, AHM. Critical revisions for important intellectual content: AHM, RAA.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Seidman G, Unnikrishnan S, Kenny E, et al. Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care practice: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):1-20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125643 [ Links ]

2. Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7(1):e37-4E6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30451-0 [ Links ]

3. Hug L, Alexander M, You D, Alkema L. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Heal 2019;7(6):e710-e720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30163-9 [ Links ]

4. Ameh CA, Van Den Broek N. Making it happen: Training health-care providers in emergency obstetric and newborn care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2015;29(8):1077-1091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.03.019 [ Links ]

5. Uwaezuoke S. Kangaroo mother care in resource-limited settings: Implementation, health benefits, and cost-effectiveness. Res Reports Neonatol 2017; 7:11-18. [ Links ]

6. Almgren M. Benefits of skin-to-skin contact during the neonatal period: Governed by epigenetic mechanisms? Genes Dis 2018;5(1):24-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2018.01.004 [ Links ]

7. Chisenga JZ, Chalanda M, Ngwale M. Kangaroo mother care: A review of mothers' experiences at Bwaila hospital and Zomba Central hospital (Malawi). Midwifery 2015;31(2):305-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2014.04.008 [ Links ]

8. Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Utility of kangaroo mother care in preterm and low birthweight infants. S Afr Fam Pract 2013;55(4):340-344. [ Links ]

9. Chan G, Bergelson I, Smith ER, Skotnes T, Wall S. Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care implementation from a health systems perspective: A systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:1466-1475. [ Links ]

10. Abbasi-Shavazi M, Hajataghaiee SS, Sadeghian H, Shadkam MN, Askarishahi M. Perceived benefits and barriers of mothers with premature infant to kangaroo mother care. Int J Pediatr 2018;7(4):9237-9248. [ Links ]

11. Rhoda N, Velaphi S, Gebhardt GS, Kauchali S, Barron P. Reducing neonatal deaths in South Africa: Progress and challenges. S Afr Med J 2018;108(3b):9-16. https://doi.org/10.7196%2FSAMJ.2017.v108i3b.12804 [ Links ]

12. Bergh AM, van Rooyen E, Pattinson RC. Scaling up kangaroo mother care in South Africa: 'On-site' versus 'off-site' educational facilitation. Hum Resour Health 2008;6:1-6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-6-13 [ Links ]

13. Feucht U, van Rooyen E, Skhosana R, Bergh AM. Taking kangaroo mother care forward in South Africa: The role of district clinical specialist teams. S Afr Med J 2016;106(1):49-52. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i1.10149 [ Links ]

14. UNICEF. Improving Newborn Care in South Africa: Lessons learned from the Limpopo Initiative for Newborn Care (LINC). New York: UNICEF, 2011:50. [ Links ]

15. McNarry G, Allen-Collinson J, Evans AB. Reflexivity and bracketing in sociological phenomenological research: Researching the competitive swimming lifeworld. Qual Res Sport Exerc Heal 2019;11(1):138-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1506498 [ Links ]

16. Goodman-Scott E, Carlisle R, Clark M, Burgess M. 'A Powerful Tool': A phenomenological study of school counselors' experiences with social stories. Prof Sch Couns 2016;20(1):25-35. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-20.L25 [ Links ]

17. Lindberg B, Öhrling K. Experiences of having a prematurely born infant from the perspective of mothers in Northern Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health 2008;67(5):461-471. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v67i5.18353 [ Links ]

18. Jafari M, Farajzadeh F, Asgharlu Z, Derakhshani N, Asl YP. Effect of kangaroo mother care on hospital management indicators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Educ Health Promot 2019;8:96. https://doi.org/10.4103%2Fjehp.jehp_310_18 [ Links ]

19. Kumbhojkar S, Mokase Y, Sarawade S. Kangaroo mother care (KMC): An alternative to conventional method of care for low birth weight babies. Int J Heal Sci Res 2016;6(3):36-42. [ Links ]

20. Chavula K, Guenther T, Valsangkar B, et al. Improving skin-to-skin practice for babies in kangaroo mother care in Malawi through the use of a customised baby wrap: A randomised control trial. PLoS ONE 2020;15(3):1-16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229720 [ Links ]

21. Joshi M, Sahoo T, Thukral A, Joshi P, Sethi A, Agarwal R. Improving duration of kangaroo mother care in a tertiary-care neonatal unit: A quality improvement initiative. Indian Pediatr 2018;55(9):744-747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-018-1372-7 [ Links ]

22. Kiwanuka A, Tarabani S, Mbao EH, Kisanga F. Challenges facing mothers who practice kangaroo mother care in health facilities; a case of Dar es Salaam. Int J Nurs Heal Sci 2017;4(5):58-62. http://www.openscienceonline.com/journal/ijnhs [ Links ]

23. Lewis TP, Andrews KG, Shenberger E, et al. Caregiving can be costly: A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to conducting kangaroo mother care in a US tertiary hospital neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Preg Childbirth 2019;19(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2363-y [ Links ]

24. Jamali QZ, Shah R, Shahid F, et al. Barriers and enablers for practicing kangaroo mother care (KMC) in rural Sindh, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2019;14(6):1-15. https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0213225 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R A Anokwuru

rafiat12@gmail.com

Accepted 28 October 2020