Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Child Health

versão On-line ISSN 1999-7671

versão impressa ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.13 no.3 Pretoria Set. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCH.2019.v13i3.1479

ARTICLE

Determinants of preterm delivery in the central zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia: A case-control study

F T WudieI; F A TesfamichealII; H Z FissehaIII; N B WeldehawariaIV; K H MisgenaIV; H B AlemaIV; Y S GebregziabherIV; G K FissehaIV; M G WolduIV

IMPH; Department of Pharmacy , Aksum University Referral Hospital, Ethiopia

IIPhD; Department of Public Health, College of Health Science, Jimma University, Ethiopia

IIIMSc; Department of Public Health, College of Health Science, Arsi University, Assella, Ethiopia

IVMPH; Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Aksum University, Ethiopia

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Preterm birth remains one of the most serious problems in obstetrics care globally. In Ethiopia preterm delivery is a direct cause of 28% newborn deaths. However, little is known about the risk factors of preterm birth.

OBJECTIVE. To determine risk factors of preterm birth in Tigray, Ethiopia.

METHODS. A hospital-based, unmatched case-control study was conducted among 288 respondents (cases=96; controls=192). Data were collected during individual interviews and through a chart review. Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics and bivariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis (significance level p<0.05).

RESULTS. The response rate was 100%. The mean (standard deviation) age of the respondents was 26.1 (5.9) years. Urban residence (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 3.11; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.181 - 8.168)), gynaecological problems (aOR 8.9; 95% CI 1.580 - 50.252), hard physical work during pregnancy (aOR 3.85; 95% CI 1.622 - 9.144), being younger than 18 (aOR 4.56; 95% CI 1.702 - 12.215) and being a first-time mother (aOR 4.66; 95% CI 1.635 - 13.254) were identified as statiscally significant risk factors of preterm delivery. Micronutrient supplementation (aOR 0.26; 95% CI 0.008 - 0.084) and nutritional counselling during pregnancy (aOR 0.24; 95% CI 0.067 - 0.862) were identified as protective factors against preterm birth.

CONCLUSION. The study identified various factors associated with an increased risk of preterm birth and also some protective factors against preterm birth. Programmes to improve maternal and newborn healthcare are recommended to reduce the incidence of preterm births in this region.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines preterm birth as the birth of an infant earlier than 37 weeks (259 days) of gestation.[1] The almost 15 million preterm births recorded globally in 2010 represented more than one in ten live births,[1] with approximately 25% of newborn deaths recorded annually attributed directly to prematurity and 30% to secondary infections.[2,3] In addition, ~90% of preterm births and 99% of preterm deaths occur in developing countries.[4] In many low-income countries, only 30% of infants born between 28 and 32 weeks survive and almost all infants born earlier than 28 weeks die during the first few days of life. In these settings, the majority of deaths occur where primary care is not available.[1-4] In Ethiopia, specifically, preterm births contribute directly to 28% of newborn deaths.[5-7]

Preterm birth often leads to lifelong complications, including neurodevelopmental impairment and disabilities such as learning difficulties, hearing impairment and behavioural problems, chronic lung disease, retinopathy of prematurity and lower growth achievement.[6] Preterm birth also affects the infant's family, who may have to spend substantial time and financial resources to care for the newborn. Preterm birth therefore has considerable cost implications not only for families but also for a country's health services.[8]

The cause of preterm birth is unknown in almost half the cases.[5,9-Some risk factors have been identified, for example sociodemographic factors, history of obstetric abnormalities, intrauterine infections, pregnancy-related irregularities, and genetic and environmental factors.[1,4,10-16] However, the complexity and overlap of risk factors are not well understood and their mechanisms are unknown in most cases. Low socioeconomic status has been identified as a contributing factor in preterm births.[12-17] This may be attributed to women from low-income settings often experiencing nutritional deficiencies, insufficient healthcare, a low level of education and a stressful life.[13] Studies also show that a previous preterm delivery substantially increases a woman's risk of a subsequent spontaneous preterm delivery.[11,14,15,18,19] Multiple pregnancies and stillbirth have also been identified as risk factors for preterm delivery.[17-19]

The aetiology of preterm births is multifactorial and evidence suggests that the prevalence varies depending on geographical and demographic features. To reduce the burden of preterm births, effective maternal care, including specific and comprehensive obstetric care for preterm newborns, is required.[20] Despite it being known that maternal complications and social settings have a substantial role in the underlying risk of preterm delivery, the magnitude and risk factors of premature births are not clearly known in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting and design

The study was conducted in the central zone of the Tigray Regional State, which is approximately 1 000 km from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia's capital, and 220 km from the regional capital, Mekelle. There are 54 governmental health centres and seven hospitals in the study area. Three of the hospitals offer general care, whereas the remaining four offer primary care. To identify predictors of preterm birth, an institution-based, unmatched case-control study was conducted in all the hospitals in the study area between 1 and 30 October 2016.

Sampling description

The sample size was estimated according to the double population proportion formula in EPI Info version 7 (CDC, USA). With a case-control ratio of 1:2, an estimated odds ratio (OR) of 3.81 and a 10% non-response rate expected, the total calculated sample size was 288 (96 cases and 192 controls). Convenience sampling was used to sample a proportional number of cases and controls from each study site based on its population size (Fig. 1).

Assuming that cases would present randomly, we included all women who gave birth during the study period until the specified number of participants had been reached at the respective sites. This approach contributed to minimising selection bias.

Cases were defined as women whose infants were born prematurely, whereas controls were those who gave birth at normal gestational age. Mothers of stillborns or women who gave birth earlier than 28 weeks or later than 42 weeks of gestation were excluded. Women who were severely ill and unable to communicate were also excluded.

Data collection

Seven trained data collectors obtained data from participants through chart reviews and individual interviews, using a pretested questionnaire. The data collectors were all healthcare professionals, but did not work in the study area. The data collection process was supervised by members of the research team. The data sets described in the manuscript are available on request, in a way that preserves anonymity.

Data analysis

Data were entered into a software application (EPI Info, version 7) and then exported to SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., USA) for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe qualitative variables. Chi-squared tests were used to assess the association of categorical variables with preterm birth. To identify determinants of preterm birth, an initial bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to observe the effect of each independent variable, without controlling for effects of other predictors. Variables with p-values <0.2 were considered potential candidates for multivariate analysis. A multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was developed using stepwise regression. According to this technique, identified variables are added one at a time and variables that become obsolete can be removed at any time during model development. A likelihood ratio test was used to identify confounding factors and interaction effects. Variance inflation factors were considered to identify multicollinearity; there is no statistically significant collinearity between variables in the final model. The model's overall goodness of fit and prediction power were assessed according to the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and receiver operating characteristics, respectively. A significance level of p<0.05 was used throughout.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the College of Health Sciences, Aksum University. The official ethical clearance letter was submitted to the Tigray Regional Health Bureau, who subsequently issued permission letters for conducting the study at the various selected hospitals. Finally, the chief executive officers at each hospital gave permission to conduct the study in the respective departments.

Informed consent was obtained verbally from each participant before an interview. Participants were informed of their right to accept or deny participation in our study. Information was treated as confidential and was used only for research purposes.

Operational definitions

The following operational definitions pertain to the study:

• Abortion: The termination of a pregnancy earlier than 28 weeks of gestation; this is not considered a preterm delivery in the context of this study.

• Preterm birth: An infant born between 28 and 37 weeks of gestation.

• Full-term birth: An infant born between 37 and 42 weeks of gestation.

• Post-term birth: An infant born after 42 full weeks of gestation.

• Gynaecological problem: Any type of gynaecological problem, such as problems of the uterus or cervix.

• Spousal care: A spouse's support to a woman during her pregnancy, including assuming household responsibilities.

• Heavy activities: Activities that are performed with difficulty during a woman's pregnancy.

• Infection during pregnancy: Any infection of the reproductive system experienced during pregnancy, including urinary tract infections.

Results

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

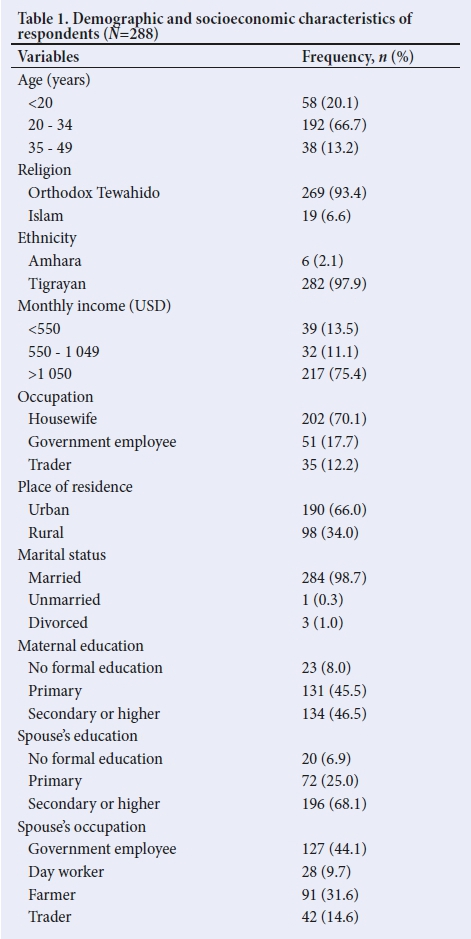

Complete data sets were obtained from 288 participants, which gives a response rate of 100%. Approximately two-thirds of the respondents (n =190; 66%) were from urban areas. Almost all the respondents were married (n =284; 98.6%) and of the Tigrayan ethnic group (n =282; 97.9%). The majority of the respondents indicated their religion as Orthodox Tewahido (n =269; 93.4%). The mean (standard deviation) age of the study participants was 26.1 (5.9) years, with two-thirds of the respondents being between 20 and 34 years of age (n =192; 66.7%) (Table 1).

Obstetric and nutritional characteristics

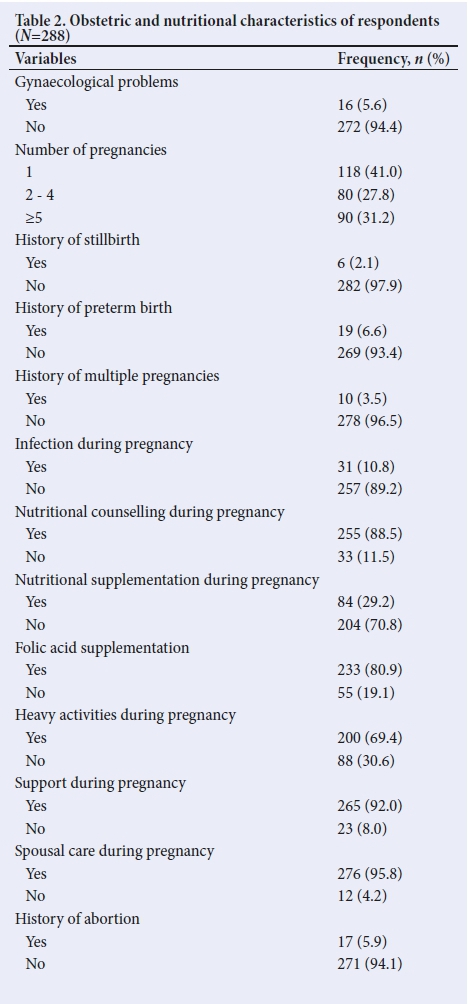

Gynaecological problems were reported by 16 respondents (5.6%) and 31 (10.8%) reported an infection during their pregnancy (Table 2). In addition, 19 (6.6%), 10 (3.5%) and 6 (2.1%) of the respondents

had a history of preterm delivery, multiple pregnancies and stillbirth, respectively. The majority of the respondents (n =255; 88.5%) had received nutrition advice during their pregnancy and more than a quarter (n =84; 29.2%) used nutritional supplements during their pregnancy. A fifth of the deliveries were through caesarean section (Table 3).

A similar proportion of respondents were married before and after 18 years of age. A fairly small proportion of respondents (n =38,;13.2%) had their first delivery before the age of 18 years, whereas 86.8% were 18 years or older at their first delivery.

The majority of respondents (n =270; 93.8%) had at least one antenatal clinic visit during their last pregnancy. Only approximately a third of the respondents (n =101; 35.1%) attended an antenatal clinic four times or more during their pregnancy, as is recommended, whereas 187 (64.9%) reported that they had fewer than four visits to an antenatal clinic.

Of the respondents, 118 (41%) reported the pregnancy to have been their first, whereas 27.8% of the respondents reported having been pregnant up to four times before and 31.2% reported the current pregnancy to have been their fifth or later (Table 3).

Factors associated with preterm delivery

The bivariate analysis (Table 4) showed that women with a history of a previous preterm delivery, multiple pregnancies or stillbirth were more likely to experience a preterm delivery than women without such histories (previous preterm delivery: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 5.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.968 - 32.254; multiple pregnancies: aOR 6.35, 95% CI 0.857 - 47.056; stillbirth: aOR 3.99, 95% CI 0.324 - 49.143).

The multivariate analysis showed women from urban areas to be 3.11 times (95% CI 1.181 - 8.168) more likely to experience a preterm delivery than those from rural areas. Women with gynaecological problems were 8.91 times (95% CI 1.580 - 50.252) more likely to experience a preterm delivery than those without such problems. Women who gave birth before the age of 18 were 4.6 times (aOR 4.56, 95% CI 1.702 - 12.215) more likely to have a preterm delivery than those who were 18 years or older at the time of their first pregnancy. A preterm delivery was 4.7 times more likely among women who were pregnant for the first time (aOR 4.66, 95% CI 1.635 - 13.254) than among those who had been pregnant before. Women who did strenuous physical activity during pregnancy were 3.9 times (aOR 3.85, 95% CI 1.622 - 9.144) more likely to have a preterm delivery than those who did not perform such activities. Women who received nutritional supplementation, nutrition advice and had some form of support during their pregnancy were 74% (aOR 0.26, 95% CI 0.008 - 0.084), 76% (aOR 0.24, 95% CI 0.067 - 0.862) and 82% (aOR 0.18, 95% CI 0.042 - 0.802) less likely to experience a preterm delivery, respectively.

Discussion

This study assessed predictors of preterm births among mothers in the central zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. In this study, 94% participants attended an antenatal clinic at least once. Although this is higher than the universal proportion, only 35% of participants reported at least four visits. With effective prenatal care, risk factors of preterm birth and other complications of pregnancy can be identified and managed.[18,19] Between 2007 and 2014, approximately 83% of women worldwide received antenatal care at least once during their pregnancies and 64% reported the WHO-recommended four antenatal clinic visits.[21-23]

Various studies have indicated that sociodemographic characteristics (including low socioeconomic status), history of obstetric abnormalities, intrauterine infections, and genetic and environmental factors are associated with preterm births.[11-16,24,25] The association between socioeconomic status and preterm delivery may be related to women in low-income settings often experiencing nutritional deficiencies, having insufficient healthcare, a low level of education and a stressful life.[13,24]

Our findings reflect similar interpretation. Place of residence, gynaecological problems, number of pregnancies, frequency of antenatal care, strenuous activity, support during pregnancy, micronutrient supplementation, additional food intake and nutritional counselling during pregnancy were identified as factors to be considered when assessing predictors of preterm birth; micronutrient supplementation, nutritional advice and additional nutrition intake during pregnancy were identified as protective factors against premature delivery.

Women from urban areas were three times more likely to have a preterm delivery than women in rural areas. In contrast, a 2016 study from northern Ethiopia reported that mothers from rural areas were at higher risk of preterm delivery than mothers from urban areas.[24] The discrepancy might be due to the difference in lifestyle and socioeconomic status of the subjects.

In our study, first-time mothers were 4.7 times more likely to experience a preterm delivery than those who have had children before. A study by Alijahan et al.[11]reported that the increased risk seen in first-time pregnancies was not statistically significant. However, findings from a multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health and also one conducted in Jimma, Ethiopia, show that women who have given birth before were at higher risk of preterm deliery than first-time mothers.[26,27] Our study also shows that women who did not attend an antenatal clinic regularly were at higher risk of having a preterm birth, as has been found also in other studies[15,16] and specifically also in a study from the Amhara Regional State in Ethiopia.[23] Research evidence suggests that effective prenatal care can help to identify and manage risk factors of preterm birth and pregnancy-related complications.[18]

The finding that gynaecological problems appear to be a notable risk factor for preterm birth is in line with findings from elsewhere in the world.[18-20,27] Similar to other studies, we also found a history of multiple pregnancies to infer a higher risk of preterm delivery.[18,19,27-This is supported by findings that show that premature birth occurs in about 50% of non-singleton births.[7] Our finding that a history of stillbirth increases the risk of a preterm delivery birth is supported by some previous studies,[10,18,19,27] although not consistently.[23,25-

Preterm birth is a complex condition and likely a combination of genetic and environmental factors.[28] Various studies indicate history of preterm birth as a risk factor for recurrent preterm birth.[11,15,18-20,27]The occurrence of preterm birth in such cases appears to range from 15% to 50%, depending on gestational age at which earlier deliveries occurred.[22,28]

Women younger than 18 when they gave birth were 4.7 times more likely to have a premature delivery. This is in line with findings by Smith et al.[29]The increased risk in younger women may be related to reproductive system development. In our study, women who were supported during their pregnancy were 82% less likely to experience preterm birth, whereas those who engaged in strenuous physical work had a notably higher risk for preterm delivery. Similar observations were seen in an Iranian study,[11] although the study by Abu Hamad et al.[18] does not show the mother's level of physical activity to be associated with preterm birth.

Study limitations

Our study included only a single zone in the region, which reduces the generalisability of the results. Recall bias, as can occur in case-control studies, may have occurred.

Conclusion

Living in an urban area, gynaecological problems, limited visits to an antenatal clinic, doing hard physical work during pregnancy, giving birth before the age of18 and a first pregnancy were identified as factors positively associated with preterm delivery. In contrast, micronutrient supplementation, additional food intake, nutritional advice and support during a pregnancy appeared to protect against preterm delivery. Efforts to improve existing maternal healthcare services in the region are recommended. Research at regional or country level, involving a larger sample size and mixed study design, is suggested to inform a better understanding about preterm birth and the associated risk factors in Ethiopia.

Acknowledgements. The authors acknowledge the Aksum University College of Health Science and the Tigray Regional Health Bureau for permission to conduct the study. We also thank the various hospitals and study participants for their support during the study.

Author contributions. FT was responsible for study conceptualisation and design, and participated in all aspects of data collection and analysis. HZ and MG contributed to study design and data analysis and wrote the manuscript. GK and HB were involved in designing the study and contributed to data collection and analysis. KH, NB and YS contributed to data analysis and finalising the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162-2172. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60820-4 [ Links ]

2. Iams JD, Romero R, Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL. Primary, secondary and tertiary interventions to reduce the morbidity and mortality of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:164-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60108-7 [ Links ]

3. Barros FC, Bhutta ZA, Batra M, et al. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (3 of 7): Evidence for effectiveness of interventions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10(Suppl 1):S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-10-s1-s3 [ Links ]

4. Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: A systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88(1):31-38. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.08.062554 [ Links ]

5. World Health Organization (WHO). Coverage of maternity care: A listing of available information. Geneva: WHO, 1997. [ Links ]

6. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet 2005;365(9462):891-900. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)71048-5 [ Links ]

7. Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, Rubens CE, Stanton C, GAPPS Review Group. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): Definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10 (Suppl 1):S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-10-s1-s1 [ Links ]

8. Van den Broek NR, Jean-Baptiste R, Neilson JP. Factors associated with preterm, early preterm and late preterm birth in Malawi. PLoS One 2014;9(3):e90128. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090128. [ Links ]

9. Mettal A. Maternal hemoglobin and premature child delivery. East Mediterr Health J 1998;4(3):480-486. [ Links ]

10. Sulima M, Lewicka M, Wiktor K, Wiktor H. Analysis of preterm delivery risk factors - a literature review. J Pub Health Nursing and Med Resc 2013;4:9-15. [ Links ]

11. Alijahan R, Hazrati S, Mirzarahimi M, Pourfarzi F, Ahmadi Hadi P. Prevalence and risk factors associated with preterm birth in Ardabil, Iran. Iran J Reprod Med 2014;12(1):47-56. [ Links ]

12. Räisänen S, Gissler M, Saari J, Kramer M, Heinonen S. Contribution of risk factors to extremely, very and moderately preterm births - register- based analysis of 1 390 742 singleton births. PLoS One 2013;8(4):e60660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060660 [ Links ]

13. Murphy D. Epidemiology and environmental factors in preterm labour. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21(5):773-789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.03.001 [ Links ]

14. Nguyen N, Savitz DA, Thorp JM. Risk factors for preterm birth in Vietnam. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004;86(1):70-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.04.003 [ Links ]

15. Khalajinia Z, Jandaghi G. Maternal risk factors associated with preterm delivery in Qom province of Iran in 2008. Sci Res Essays 2012;7(1):51-54. https://doi.org/10.5897/sre11.1009 [ Links ]

16. Dodds L, Fell DB, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B. Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107(2 Pt 1):285-292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000195060.22832.cd [ Links ]

17. Tucker J, McGuire W. Epidemiology of preterm birth. BMJ 2004;329(7467):675-678. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7467.675 [ Links ]

18. Abu Hamad K, Abed Y, Abu Hamad B. Risk factors associated with premature birth in the Gaza Strip: Hospital-based case-control study. East Mediterr Health J 2007;13(5):1132-1141. https://doi.org/10.26719/2007.13.5.1132 [ Links ]

19. Abdel Razeq NM, Khader YS, Batieha AM. The incidence, risk factors, and mortality of preterm neonates: A prospective study from Jordan (2012-2013). Turk J Obstet Gynecol 2017;14(1):28-36. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjod.62582 [ Links ]

20. Svedenkrans J, Henckel E, Kowalski J, Norman M, Bohlin K. Long-term impact of preterm birth on exercise capacity in healthy young men: A national population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e80869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080869 [ Links ]

21. World Health Organization (WHO). Antenatal care. Report of technical working group. Geneva: WHO, 1994. [ Links ]

22. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016-2030). Geneva: WHO, 2015. [ Links ]

23. Bekele T, Amanon A, Gebreslasie KZ. Preterm birth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in Debremarkos Town health institutions, 2013 institutional based cross sectional study. Gynecol Obstet 2015;5:292-297. [ Links ]

24. Mengesha HG, Lerebo WT, Kidanemariam A, Gebrezgiabher G, Berhane Y. Pre-term and post-term births: Predictors and implications on neonatal mortality in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs 2016;15:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0170-6 [ Links ]

25. Khalil KA, El-Amrawy SM, Ibrahim AG, El-Zeiny NA, Greiw AE. Pattern of growth and development of premature children at the age of two and three years in Alexandria, Egypt (Part I). East Mediterr Health J 1995;1(2):176-185. [ Links ]

26. Morisaki N, Togoobaatar G, Vogel JP, et al. Risk factors for spontaneous and provider-initiated preterm delivery in high and low Human Development Index countries: A secondary analysis of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG 2014;121 (Suppl 1):101-109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12631 [ Links ]

27. Molla IB, Demeke T, Dugna K. Prevalence of preterm birth and its associated factors among mothers delivered in Jimma University Specialized Teaching and Referral Hospital, Jimma Zone, Oromia Regional State, South West Ethiopia. J Women Health Care 2017;6:356. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0420.1000356 [ Links ]

28. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371(9606):75-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60074-4 [ Links ]

29. Smith LK, Draper ES, Manktelow BN, Dorling JS, Field DJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in very preterm birth rates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2007;92(1):F11-F14. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.090308 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

H Z Fisseha

hiwet58@yahoo.com

Accepted 8 April 2019