Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Child Health

versión On-line ISSN 1999-7671

versión impresa ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.12 spe Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajch.2018.v12i2.1514

ARTICLE

Speaking through pictures: Canvassing adolescent risk behaviours in a semi-rural community in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa

C GroenewaldI; Z EssackI, III; S KhumaloII

IPhD; Human and Social Development Unit, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa

IIMA; Human and Social Development Unit, Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa

IIIPhD; School of Law, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Adolescent risk behaviours, such as substance abuse and unprotected sex, are leading social and health challenges in South Africa (SA).

OBJECTIVE. To investigate adolescents' perspectives on the prevalence of adolescent risk behaviours in rural settings in SA.

METHOD. Using a qualitative photovoice methodology, the current study explored adolescents' perspectives and experiences of living in a peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal Province. KwaZulu-Natal is the epicentre of the South African HIV epidemic, and adolescents - especially young girls - are at heightened risk for HIV infection. Male and female participants aged 15 - 18 years (N=33) were asked to respond to a series of questions by taking photographs that best describe their perspectives or experiences.

RESULTS. The photovoice methodology allowed adolescents to represent their perspectives and experiences as experts on their lives and needs. The participants reported that adolescents in their community engage in various risky behaviours, of which risky sexual behaviours and hazardous substance use emerged as significantly problematic. Risky sexual behaviours entailed unprotected sex, having multiple sexual partners, cellphone sharing of pornography, and sex while intoxicated. Problematic substance use involved harmful drinking behaviours such as binge drinking and illicit drug use.

CONCLUSION. Contextually relevant interventions aimed at reducing adolescent engagement in risky sexual behaviours and harmful substance use need to be prioritised. Additional recommendations are discussed.

Adolescent health and behaviours have received increasing attention in the last decade, with several studies considering the impact of risk behaviours on adolescent health and wellbeing.[1,2] Adolescents are defined by the World Health Organization as young persons between 10 and 19 years old.[3] Two issues of particular concern in South Africa include the harmful use of alcohol and illicit drugs, and risky sexual practices, by adolescents. Surveillance statistics indicate that 49.2% of South African school-going youth have used alcohol and 25.1% of these youth have engaged in binge drinking.[4] Furthermore, 26% of all persons admitted to substance abuse rehabilitation facilities in 2016 were under the age of 20 years.[5]

Risky sexual behaviour is defined as sexual activities that potentially expose an individual to sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and unplanned pregnancy.[6] These include unprotected sex, early sexual debut, inconsistent condom use, alcohol or drug use before sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, forced or coerced sexual intercourse for reward, and low frequency of contraceptive use.[7,8] More than a quarter of South African school-going youth have had sex, 12% of whom had sexual debut before 14 years of age.[4] Early sexual debut increases the risk of HIV infection at a very early age.[9] Of those who had sex, only 32.9% reported consistent condom use and 18% indicated that they had been pregnant or had made someone pregnant.[4] Almost half of those who had sex reported having had multiple sexual partners, while 17% reported having used alcohol and 13% having used drugs prior to having sex.[4]

In South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal Province has the highest prevalence of HIV, consistent across all age categories, including 15 - 24-year-olds.[10] KwaZulu-Natal is often characterised as the epicentre of the South African HIV epidemic. While studies have explored the epidemiology of adolescent risk behaviours in South Africa,[11] fewer studies have canvassed the opinions of adolescents in peri-urban communities. A previous longitudinal study on the wellbeing of children conducted in Vulindlela, KwaZulu-Natal,[12] identified serious overlapping risk behaviours, particularly drug use and sexual behaviour among children. These observations highlighted the need for a more comprehensive understanding of how adolescents assess and negotiate risk in high-poverty, high-HIV-prevalence communities. Using a photovoice methodology, the current paper describes adolescents' representations of substance misuse and risky sexual practices in a low-resource, high-HIV-prevalence peri-urban community (Vulindlela) in KwaZulu-Natal.

Methods

The current paper presents findings from a larger qualitative study that explored adolescents' health behaviours and lived experiences. This study used the photovoice methodology to enable adolescents to identify and represent their experiences of what it is like being an adolescent in their community. Specifically, the participants were prompted to capture images (spontaneously or staged) that describe (i) who they are; (ii) what makes them happy; (iii) the activities they do for fun; (iv) the risks and challenges that are present for young people in the community; (v) their hopes and goals; and (vi) their culture. Photovoice is a visual participatory methodology that enables participants to represent their subjective perspectives and experiences of emerging issues through self-captured images.[13] It has been found useful in studies that have explored youth perspectives on HIV and AIDS stigma,[14] relationships and sexuality[15] and gender-based violence.[16] Focus-group discussions were arranged for the participants to present and discuss their pictures in more depth.

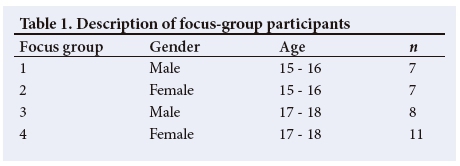

While the larger study included a wider age range (12 - 18-year-olds), only 15 - 18-year-olds (N=33) participated in the photovoice activity. Participants were recruited from schools in the local community and 4 focus groups were completed, clustered by age and sex (Table 1). The sample consisted of black isiZulu-speaking adolescent boys (n=15) and girls (n=18), who were attending school grades 8 - 12 at the time of the study.

Participants were provided with disposable cameras to capture their responses to the prompts.[17] In this way, the participants' voices are prioritised and displayed through visual evidence as well as subjective narratives. Focus-group discussions were audio-recorded with participants' consent and transcribed and translated. Coding of the transcripts was facilitated by Atlas.ti (qualitative data management software) and subsequently analysed by all three authors using thematic analysis.[18] The adolescents' photographs displayed a range of issues, including the factors that positively and negatively influence the wellbeing of young people in their community.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee. Given that participants were minors below the age of 18, we sought parental or caregiver consent, and assent from the adolescent participants.

Results

We present the participants' narratives and images of adolescent risk behaviours according to two themes, namely adolescent substance misuse and risky sexual behaviours.

Adolescent substance misuse

A theme that emerged in most of the participants' narratives was the frequent use of alcohol and other substances such as cannabis, whoonga (a cheap form of heroin laced with other harmful substances) and snuff (powdered tobacco that is snorted rather than smoked) by young people in their community. Alcohol, cannabis and whoonga were reportedly used by both male and female youth, although whoonga use was more pronounced among males.

Peer influences, through social modelling, norms and implicit peer pressure, were considered to be key contributing factors to adolescent substance misuse behaviours. One of the participants explained (Fig. 1):

'Here, I was trying to show a picture of peer pressure; that young people my age don't just start smoking and doing drugs, but friends influence them because they want to fit in ... You cannot fit in with them if you do not smoke!' (Focus group (FG) 3, male, 17 - 18).

While substances such as whoonga and snuff were identified as problematic, alcohol in particular emerged as a popular and easily accessible substance. One of the adolescent boys displays his views on underage drinking and its potentially detrimental effects on future goals and aspirations (Fig. 2).

Participant: 'This is the picture that shows risks that young people take. As you can see, they are drinking alcohol and some of them are under 18 years!'

Interviewer: ' What are the messages that you were trying to show us with this picture?'

Participant: ' The message I was trying to pass with this picture is that drinking alcohol when you under age is not good! Instead you are killing yourself and your future!'

Interviewer: ' Okay, what is it about this picture that stood out and made you decide to take it and talk about it?'

Participant: 'It just that if I see people of my age drinking alcohol, it makes me feel bad because I can see that it is not all of us who want good things in life.'

Evident in the extracts above, the participant not only presents the problem of underage drinking, but also recognises the harmful impact that early substance misuse can have on future aspirations and success; for example, 'you are killing yourself and your future. This sentiment was also expressed by other participants who indicated that using illicit substances leads to 'a destroyed future' (FG 1, male, 15 - 16) and an 'inability to perform well at school.' (FG 4, female, 17 - 18).

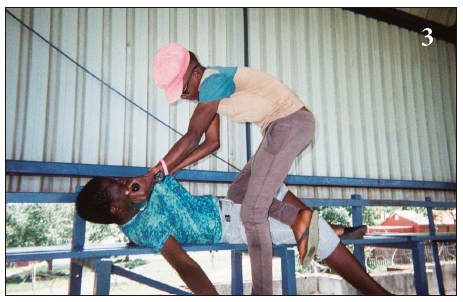

Most adolescents also acknowledged the consequences attached to substance misuse. Engagement in violent crimes such as robbery or physical fights while intoxicated was prominent in the adolescents' accounts (Fig. 3). Here the participant described the violence he often observed in his community when young men drink alcohol excessively. He explained: [W]hen they are drunk, they do bad things like stabbing each other! (FG 3, male, 17 - 18).

In all, participants generally agreed that using alcohol or other drugs is harmful to the psychosocial wellbeing of young people. Participants were generally cognisant of the detrimental effect that using alcohol during adolescents can have on future aspirations and success.

Risky sexual behaviours

Risky sexual behaviours, in the form of unprotected sex, transactional sex, multiple sexual partners and cellphone sharing of pornography, were commonly discussed by the adolescents. Importantly, the link between the use of certain substances (e.g. alcohol and snuff) and risky sexual behaviour was also described. For example, alcohol use was reported to encourage 'loose' behaviours among young women. 'Loose' behaviours included having 'sex with someone that you don't know' (FG 2, female, 15 -16), which may lead to heightened vulnerability to STIs and HIV, as well as unplanned pregnancy. Some participants explained that 'alcohol makes one crave sex' (FG 3, male, 17-18) which is seen to encourage young people to be 'loose'.

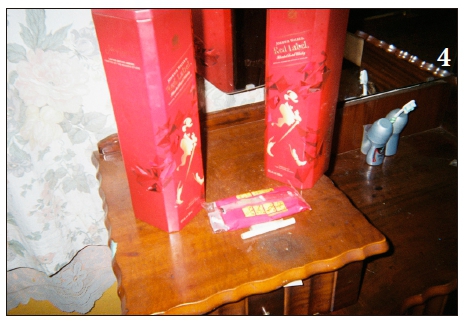

Fig. 4 depicts alcohol with cigarettes and a condom, aimed to display the link between alcohol use and sexual activity. Alcohol use was also reported to increase vulnerability to forced sex and sexual violence, for example: '[I]n most cases, it happens to the girls who go to parties, and boys like sex. If they see that a girl is drunk, it is easy for them to rape a girl! (FG 2, male, 15 - 16).

Snuff (also colloquially referred to as what's-up) was reported to be most commonly used by young girls. Although snuff was used as a mechanism to 'feel high', some of the girls explained that it is often used to enhance sexual pleasure. In Fig. 5, the participant stages a young girl preparing to use snuff and explains:

Participant: 'What I heard is that girls, like women, use it for sexual activities ... Uhm, they say it makes boys... You see when they have sex you become [aroused] and that... The sister I was sitting with told me that, you see. But she told me not to [tell other people]. She said like with your partner, what can I say? He says you are the only person that he enjoys sex with if you used that thing.

Interviewer: 'But how? When they have sex?'

Participant: 'They insert it here [pointing towards the vagina] and others that drink alcohol, they insert it underneath [inside their private parts].'

Snuff was thus reported to be used by young girls, by inserting the substance into their vaginas as a way to create a more pleasurable sexual experience for their male partners, and did not necessarily enhance sexual arousal for females directly.

Another risky sexual practice that was discussed by participants was unprotected sex. Despite an awareness of the associated risks, participants generally perceived condoms as inhibiting sexual pleasure. One participant said:

as boys, we like having sex without a condom. Pregnancy and HIV, we know all of those things! But you won't just eat a sweet with its wrapping on!' (FG1, male, 15 - 16).

This social norm was generally supported by other adolescent males in our study, which suggests that sexual pleasure might outweigh the considerations of the risks associated with unprotected sex for some participants. Multiple sexual partners were identified as a common practice amongst young people in the community. This was considered a cultural norm that is often admired by young men as explained in the quote below:

'Males are like that! It's just their lifestyle to have many women. You actually get some respect if you are known for having many women!' (FG 1, male, 15 - 16).

Similarly, another participant reported that '[I]f you are a boy, having many girlfriends will make you a name [popular], you know!! (FG 3, male, 17 - 18).

For female participants, however, having multiple sexual partners appeared to reflect the transactional nature of relationships, for example:

Participant 1: 'It happens [that you will] have four. You know one is for airtime, finance, transport and so forth .!

Participant 2: 'Yes, this one is for clothes, airtime, but I don!t sleep with all of them; you only sleep with the one you love!' (FG 4, female participants, 17 - 18).

This resonated with other female participants, who reported having sex in exchange for gifts:

Participant: 'There are famous taxi drivers, when they pass by our schools, some girls scream.'

Interviewer: 'How do these taxi drivers look?'

Participant: 'You know they have sound and swag.'

Interviewer: 'Are young girls attracted to them because of fashion?'

Participant: 'Nothing else, they give them money, buy them clothes

Interviewer: 'So is that why they love them so much?'

Participant: 'Yes, and the drivers' aim is to have sex only! He would buy you anything, but at the end, sex is central!' (FG 4, female, 17 - 18).

In talking about these common practices, most participants recognised the consequences of unprotected sex and multiple sexual partners, including the risk of contracting STIs and HIV. A strong emphasis on teenage pregnancy was also apparent in the adolescents' narratives and photos (Fig. 6). A female participant used this picture to reflect that teenage pregnancy is a challenge and to capture the negative impacts of teenage pregnancy on the academic trajectory of young women:

'It is too risky! As I have said before, that they [young women] destroy their future!... They can't carry on with the future because a baby will be here and she couldn't go back to school!' (FG 4, female, 17 - 18)

Later in the same discussion, this participant revealed that she had fallen pregnant herself. Although she managed to return to school, it was a very difficult and painful experience for her. Similar perceptions on teenage pregnancy were reported by some of the male participants. One adolescent boy said:

'They like having sex and end up pregnant. But if they don't rush, but study and be successful, they won't be [pregnant]! So this thing hurt them so much and end up being pregnant and have children while they are still children.' (FG 1, male, 15 - 16).

Moreover, many adolescents took photos of their cellphones to display the centrality of social media in their lives (Fig. 7). A key issue that emerged in relation to cellphones was the sharing of pornography, particularly by male adolescents. Among the male participants, some reported that pornography was often used by young boys to learn about different sexual positions which they then re-enacted with their partners:

Participant: 'Most boys who like sex download videos so that they can learn different styles.'

Interviewer: 'Okay, how does it help to know those styles?'

Participant: 'It helps them to satisfy their partners and change styles. We can't do the same thing every time my girl visits.' (FG 1, male, 15 - 16).

In another focus group, a few male participants reported having received pornographic pictures from their female peers: '[S]ometimes it is the girl that takes a pic of her body and sends it to you.' (FG 3, male, 17 - 18).

Sharing of pornography was less discussed by the female participants although it was generally agreed that it was a practice that boys engaged in more frequently than girls.

Discussion

Understanding the challenges that adolescents face in their communities is important for the development of contextually relevant interventions. The photovoice methodology used in our study enabled participants to visually express their concerns in a non-threatening and exciting way which ultimately encouraged open discussion and explicit representations of their perspectives and experiences. The pictures and subsequent focus-group discussions facilitated a collaborative discussion of the challenges in their communities which produced both individual and shared constructions of the participants' daily lives.

Substance misuse emerged as a key issue in the community and was also associated with other adverse outcomes; these included engagement in risky sexual behaviours, violence and diminished hope for future success. Substances that were used most often by youth included alcohol, cannabis, whoonga and snuff. The findings thus support surveillance data which indicate that alcohol and cannabis are popular substances among young South Africans.[19] The drug whoonga, a relatively new street drug also known as nyaope, has increased in popularity among young people in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng;[19] however, further research is needed to explore adolescents' perspectives and experiences of this drug.

Our findings further suggest that alcohol and drugs are easily accessible and widely available in the study site. This is not only evident in the adolescents' narratives, but also in the several pictures that they had staged to display the severity of the problem. All of the adolescents who identified substance use as a key challenge in their community were able to easily find and incorporate both full and empty bottles of alcoholic beverages. Some had also taken pictures of places where large quantities of these bottles had been dumped in their community. Some of the pictures also displayed drugs in the form of prepared cannabis (a joint or a zol) and snuff, which also appeared to be easily accessible to the participants in our study.

The adolescents' reports on the link between substance use and unsafe sexual practices resonate with previous research, which consistently shows that risky sexual behaviour and substance abuse often occur in tandem.[20,21] As with participants in the present study who reported that alcohol use allowed them to feel less inhibited or 'loose,' alcohol and drug use by adolescents has also been reported to impair sexual decision-making, rendering them less likely to practice safe sex.[22] A survey of high school adolescents in KwaZulu-Natal found that those who used alcohol or smoked cigarettes were 2-3 times more likely to be sexually active.[23] Importantly, there is also a strong correlation between alcohol consumption and sexual victimisation,[24] as pointed out by adolescents in the present study. The use of snuff by women to enhance sexual pleasure has also been reported in the literature.[25]

Several other risky sexual behaviours were reported by adolescents in the present study including multiple sexual partners, sex without a condom, and sexting. As in many countries across Africa,[26] adolescents considered 'flesh to flesh' sex as the ideal, despite being aware of the risks of HIV and unwanted pregnancy. Risky sexual behaviours, including sex without a condom, may be fuelled by perceptions that such behaviour is normative among their peers.[27]

In addition, there is empirical evidence that 'adolescents are more likely than children and adults to make risky decisions in "hot" contexts, where emotions are at stake or peers are present and social cognition is involved.[28]

South African adolescents are at high risk of HIV. This risk is amplified among young women and girls aged 15 - 24 years, who are over 4 times at higher risk than their male counterparts.[29] Findings from the larger study which focused on sexual violence and coercion found that many girls engage in transactional relationships with older men or 'blessers'.[30] Transactional sex as described by participants in this study has implications for HIV risk.[29]

Moreover, study participants, especially male, described sharing sexually explicit cellphone messages or images and accessing pornography on their cellphones. While these may not fit the definition of risky sexual behaviour since they do not necessarily result in STIs, including HIV and/or unwanted pregnancy, research has found an association between sexting (sharing explicit photographs or messages) and physical sexual activity and sexual risk behaviour.[27] There is also evidence to suggest that the relationship between pornography and sexual health is complicated as it can both facilitate and harm sexual health among adolescents.[31] Further research on the role of pornography in promoting or harming sexual health among adolescents in rural and peri-urban spaces in South Africa is needed to inform the development of contextually sensitive sex-education programmes. The current study also showed a link between youth substance use and violent behaviours where interpersonal violence was displayed in several images. The literature supports this finding as adolescent substance abuse has been identified as a risk factor for delinquency and aggression.[32]

Improved adolescent wellbeing is dependent on the availability and accessibility of good-quality programmes and interventions to facilitate positive development.[11 While generalisability is not assumed, the findings of our study offer valuable insights and directions for targeted interventions in the study site. Interventions aimed at encouraging healthy and safe decision-making practices around alcohol use and sexual behaviour are required to primarily discourage underage drinking and the harmful use of drugs in this community. These interventions should be sensitive to the gendered nature of substance use. Initiatives should also not only enhance knowledge on the harms associated with substance misuse, but also provide adolescents with skills to resist engaging in these behaviours. In addition to behavioural interventions, evidence-based structural interventions that address gender norms are required to reduce power dynamics that exist within relationships.

Conclusion

Substance misuse and engagement in risky sexual practices are key challenges that impact the wellbeing of young adolescents, including those in peri-urban communities. Designing and piloting appropriate interventions with input from adolescents themselves is a priority. It is recommended that future studies explore the extent to which female adolescents in other communities use snuff to enhance their sexual pleasure as well as the potential risks of this practice. Research on the dangers associated with the harmful use of snuff is also required. Furthermore, research on the role of cellphone pornography and sexting in promoting early sexual debut among adolescents is needed.

Study limitations

The study is not without limitations. The study participants represent the voices of school-going youth in the study site. We therefore recognise that out-of-school youth might have different perceptions and experiences. The small sample size and qualitative nature of the study also do not allow us to generalise the findings, and therefore further research is warranted to explore the breadth of the findings in similar peri-urban communities in South Africa. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the significance of substance abuse and risky sexual behaviour and that, despite knowledge and awareness of risks and consequences, behaviour change remains difficult for adolescents.

Acknowledgements. The support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CoE in Human Development. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Demography and Population Studies Programme, Schools of Public Health and Social Sciences, Faculties of Health Sciences and Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Author contributions. CG contributed to the conceptualisation, design, analysis, interpretation of data and approval of the version of the paper submitted for review; ZE contributed to the conceptualisation, design, analysis and interpretation of data; SK contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding. The authors acknowledge the seed funding support they received from the Human and Social Development Unit of the Human Sciences Research Council.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Cooper D, De Lannoy A, Rule C. Youth health and wellbeing: Why it matters. In: DeLannoy A, Swartz S, Lake L, Smith C, eds. Child Gauge. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2015:60-68. http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/367/Child_Gauge/ South_African_Child_Gauge_2015/ Child_Gauge_2015-Health.pdf (accessed 5 December 2017). [ Links ]

2. Bhana A, Mellins CA, Petersen I, et al. The VUKA family program: Piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care 2014;26(1):1. [ Links ]

3. Sacks D, Canadian Paediatric Society Adolescent Health Committee. Age limits and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2003:8(9):577-578. [ Links ]

4. Reddy P, James S, Sewpaul R, et al. Umthente Uhlaba Usamila - The 3rd South African National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey 2011. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council; 2013. [ Links ]

5. Dada S. Own analysis of the 2016 SACENDU data on the total number of patients admitted for the period January to December 2016. 2017. [ Links ]

6. Hall PA, Holmqvist M, Sherry SB. Risky adolescent sexual behavior: A psychological perspective for primary care clinicians. Topics in Advance Practice Nursing eJournal 2004;4(1). https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/467059 (accessed 5 December 2017). [ Links ]

7. Jonas K, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, Sewpaul R, Reddy P. Teenage pregnancy rates and associations with other health risk behaviours: A three-wave cross-sectional study among South African school-going adolescents. Reproductive Health 2016;13(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0170-8 [ Links ]

8. Oluwatoyin FE, Oyetunde MO. Risky sexual behavior among secondary school adolescents in Ibadan North Local Government Area, Nigeria. JNHS 2014;3:34-44. [ Links ]

9. Zuma K, Shisana O, Rehle TM, et al. New insights into HIV epidemic in South Africa: Key findings from the National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Afr J AIDS Res 2016; 15(1): 67-75. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2016.1153491 [ Links ]

10. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Pretoria: HSRC; 2014. [ Links ]

11. Dada S, Burnhams NH, Erasmus J, et al. South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU): Research brief. Vol. 20(2). Tygerberg, Cape Town: Medical Research Council; 2017. [ Links ]

12. Knight L, Roberts BJ, Aber JL, Richter L, Size Research Group. Household shocks and coping strategies in rural and peri-urban South Africa: Baseline data from the Size Study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int Development 2015;27(2):213-233. [ Links ]

13. Peabody CG. Using photovoice as a tool to engage social work students in social justice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work 2013;33(3):251-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2013.795922 [ Links ]

14. Moletsane R, de Lange N, Mitchell C, et al. Photo-voice as a tool for analysis and activism in response to HIV and AIDS stigmatisation in a rural KwaZulu-Natal school. Journal of Child Adolescent Mental Health 2007;19(1):19-28. http://doi.org/10.2989/17280580709486632 [ Links ]

15. Holman ES, Harbour CK, Said RV, Figueroa ME. Regarding realities: Using photo-based projective techniques to elicit normative and alternative discourses on gender, relationships, and sexuality in Mozambique. Global Public Health 2016; 11(5-6):719-741. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1170870 [ Links ]

16. Mitchell C. What's participation got to do with it? Visual methodologies in 'Girl-Method' to address gender-based violence in the time of AIDS. Global Studies of Childhood 2011;1(1): 51-59. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2011.1.1.51 [ Links ]

17. Molloy JK. Photovoice as a tool for social justice workers. J Progressive Human Services 2007;18(2):39-55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J059v18n02_04 [ Links ]

18. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research Psychology 2006;3(2):77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

19. Dada S, Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and drug abuse treatment admissions in South Africa: July-December 2016 (Research Brief, 20(1)). Parow: Medical Research Council; 2017. http://www.mrc.ac.za/adarg/sacendu/SACENDUBriefJuly2017.pdf (accessed 5 December 2017). [ Links ]

20. Smith EA, Palen LA, Caldwell LL, et al. Substance use and sexual risk prevention in Cape Town, South Africa: An evaluation of the HealthWise program. Prevention Science 2008;9(4):311-321. [ Links ]

21. Ritchwood TD, Ford H, DeCoster J, Sutton M, Lochman JE. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review 2015;52:74-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.005 [ Links ]

22. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Schootman M, Cottler LB, Bierut LJ. Substance use and the risk for sexual intercourse with and without a history of teenage pregnancy among adolescent females. J Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2011;72(2):194-198. [ Links ]

23. Taylor M, Jinabhai CC, Naidoo K, Kleinschmidt I, Dlamini SB. An epidemiological perspective of substance use among high school pupils in rural KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Med J 2003;93(2):136-140. [ Links ]

24. Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol consumption and women's vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women's drinking prevent rape? Substance Use & Misuse 2009;44(9-10):1349-1376. http://doi.org/10.1080/10826080902961468 [ Links ]

25. Gafos M, Mzimela M, Sukazi S, et al. Intravaginal insertion in KwaZulu-Natal: Sexual practices and preferences in the context of microbicide gel use. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2010;12(8);929-942. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2010.507876 [ Links ]

26. Embleton L, Wachira J, Kamanda A, et al. Eating sweets without the wrapper: Perceptions of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among street youth in western Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality 2016;18(3):337-348. http://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1082626 [ Links ]

27. Rice E, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, et al. Sexually explicit cell phone messaging associated with sexual risk among adolescents. Pediatrics 2012;130(4):667-673. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0021 [ Links ]

28. Blakemore SJ, Robbins TW. Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nature Neuroscience 2012;15(9):1184-1191. http://doi:10.1038/nn.3177 [ Links ]

29. Dellar RC, Dlamini S, Karim QA. Adolescent girls and young women: Key populations for HIV epidemic control. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18(251). http://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.2.19408 [ Links ]

30. Ngidi N, Khumalo S, Essack Z, Groenewald C. Pictures speak for themselves: Youth engaging through photovoice to describe sexual violence in their community. In: Mitchell C, Moletsane R, editors. Youth Engagement through the Arts and Visual Practices to Address Sexual Violence. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers (in press). [ Links ]

31. Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000-2009. J Research on Adolescence 2011;21(1):242-255. [ Links ]

32. Doran N, Luczak S, Bekman N, et al. Adolescent substance use and aggression. Criminal Justice Behav 2012; 39(6):748-769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812437022 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C Groenewald

crule@hsrc.ac.za

Accepted 9 May 2018.