Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Child Health

On-line version ISSN 1999-7671

Print version ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.12 spe Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajch.2018.v12i2.1523

ARTICLE

Teenage pregnancy in South Africa: Where are the young men involved?

C O OdimegwuI; E O AmooII; N de WetI

IPhD; Demography and Population Studies, Faculties of Health Sciences and Social Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIPhD; Programme of Demography and Social Statistics, College of Business and Social Sciences, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. The level of unintended pregnancies among teenage girls in South Africa (SA) has remained a public health concern. However, studies and interventions generally do not consider young men's involvement in teenage pregnancies.

OBJECTIVE. To investigate the sociodemographic and sexual behaviour characteristics of young men who have impregnated at least one teenage girl.

METHODS. The study used data from the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (2009), which included responses from young men (aged 12 - 22 years) across all SA provinces. Univariate and bivariate analyses and binary logistic regression were performed.

RESULTS. The results showed that 93.2% of the sample had >2 lifetime sexual partners, 22.4% rarely used condoms and 11.5% had never used condoms. Teenage pregnancy incidence was >35% in all provinces except Gauteng and the Western Cape. The likelihood of being involved in a teenage pregnancy was higher among respondents who reported having >2 lifetime sexual partners (odds ratio (OR) 2.510; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.43 - 14.77). Respondents with a higher education were less likely to be involved in a teenage pregnancy (OR 0.819; 95% CI 0.36 - 1.84) than those with a lower education (OR 1.219; 95% CI 0.59 - 2.50).

CONCLUSION. Engaging in multiple sexual partnerships could increase the vulnerability of young people to sexually transmitted infections or teenage pregnancies. Initiatives to create awareness among SA youth regarding the consequences of sexual behaviour are recommended, with a specific focus on addressing young men's involvement in teenage pregnancy.

Reducing teenage pregnancies has been a topical focus on the development agenda for decades. Although the number of teenage pregnancies has declined drastically in most developed nations, it remains high in less-developed nations. In South Africa (SA), more than 30% of teenage girls fall pregnant,[1] while between 65% and 71% of the pregnancies among the youth are unplanned.[2,3] Despite the adolescent pregnancy rate declining from 30% in 1984 to 23% in 2008,[4] adolescents still contributed to 13.6% of the registered births in the country in 2016, a rate far higher than in other high-income countries.[5,6] The Department of Basic Education observed that about 68 000 school-going learners had given birth to at least one child in 2013, compared with 50 000 in 2009, and an additional 21 000 learners were pregnant in 2013.[7,8]

In recent years, teenage pregnancy in SA has reached alarming proportions: in 2006 alone, there was a case of one school with 144 pregnant girls.[9] The situation is similar in a number of SA provinces, especially in the Eastern Cape, Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal,[7] with more than 17 000 teenagers falling pregnant in KwaZulu-Natal alone in 2010.[10,11] In Gauteng the rate of teenage pregnancies/births increased from 1 169 in 2005 to 2 336 in 2006. Another report indicated that in KwaZulu-Natal, teenage pregnancy rates were recorded as 21.8% and 25.8% in 2002 and 2008, respectively.[12] Despite an overall decline in fertility rate in SA, the fertility rate among young women (15 - 19 years) is rising.[7] The mean age at sexual debut is as young as 14.9 years among girls in rural areas of the Eastern Cape[13,14] and ~16.4 years in Gauteng and the Western Cape.[15,16]

There have been a number of international initiatives aimed at curbing teenage pregnancies since the early 1990s. For example, the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development called on nations to embark on education initiatives for girls and to provide services to adolescents that would allow them to deal with their sexuality and make responsible decisions about sexual relationships.[17] The 1992 Forum for African Women Educationalists promoted education of girls in several African countries and supported policy reformation that would permit pregnant girls and mothering teens to complete their education.[12] The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women also promoted education initiatives focusing on sexuality, reproductive health and women's rights, which included awareness campaigns around unplanned and teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases.[18,19] More recent initiatives include the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (UN) and the African Agenda 2030.

Local initiatives to address teenage pregnancies include the Men as Partners programme,[20] the Gender Policy Framework of SA, the LoveLife campaign, the Born Free dialogues and a number of programmes to curb HIV infections among the youth.[21,22] Despite extensive programmes, considerable financial investment and several studies and reports on teenage pregnancy, the increasing proportion of unintended pregnancies among teenagers has remained a public health concern in SA.[13,14] While several factors have been implicated, including limited use of contraceptives, low abortion rates, age at sexual debut, girls' limited access to education and other socioeconomic factors,[6,14,23,24] the involvement of young men has not been considered as a contributing factor to the high teenage pregnancy rate in SA.

Teenage pregnancy involves both the girl and her male partner and the characteristics of these young men could be a fundamental underlying factor in teenage pregnancy,[25] which should not be ignored. Despite the SA government's support for a number of laws and policies related to gender-based violence, paternity establishment, child support and gender equality, there is no clear policy to engage young men who may be drivers of teenage pregnancy; to date, there have been no noticeable initiatives to sensitise young men about the implications of impregnating girls.[25]

Teenage pregnancy is often described and analysed as being a female adolescent problem.[5,7,13,14,26] However, a man's sexual relationship with a teenage girl is a critical component of a teenage pregnancy. Focusing only on the girls when investigating the factors driving teenage pregnancies would therefore not only make the treatment or analysis of the outcome (pregnancy) scientifically skewed but could also make eradication of teenage pregnancy impossible. As little is known about the interplay between the characteristics of young men who engage in sex with teenage girls and the incidence of teenage pregnancy, this study aims to investigate the sociodemographic characteristics of young men in these relationships and to identify sexual behaviour indicators that are risk factors in teenage pregnancy. In this study, young men's involvement in teenage pregnancy conceptually refers to young men's sexual relationship with teenage girls or their causing at least one teenage pregnancy.

The findings from this study may help to focus public attention on young men's involvement in teenage pregnancies and could contribute to policies around this issue.

Methods

Research design

The study used youth lifestyle data from the Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention (CJCP) 2009 dataset, focusing on youth aged 12 - 22 years. The data cover all nine SA provinces (Gauteng, Limpopo, Free State, Mpumalanga, North West, Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape), are representative of all races (white, black African, Asian/Indian and coloured) and include young men living in metropolitan, urban and rural areas. The description of metropolitan, urban and rural areas follows the description of the National Planning Commission (2011) and work by Atkinson.[27] For the purposes of this study, an urban area refers mostly to cities and towns, which are characterised by a high population density and a built environment that includes secondary and tertiary towns (often noted as townships) resulting from urbanisation.[27-29] Rural areas are mostly located in the countryside, outside of towns and cities, and are usually characterised by a low population density and small settlements.[27-29] A metropolis refers to an extended urban area that consists of several large towns or cities merging with the suburbs of a central city. These include large townships, the capital city of a country or important hubs for regional or international connections.[27,30-32]

Data and measurements

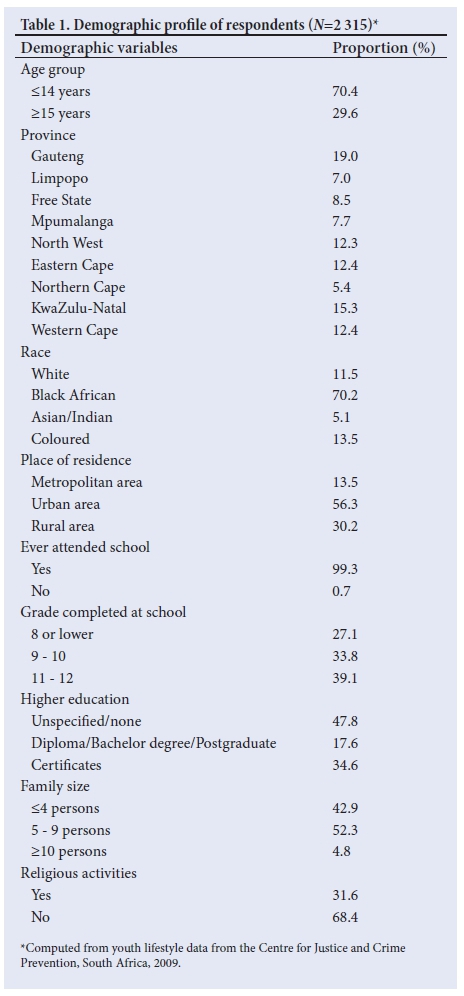

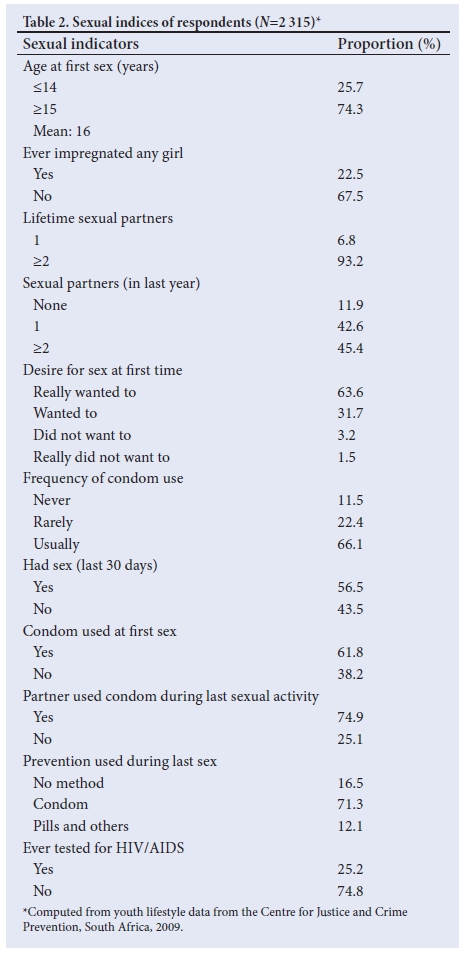

The study adopted the UN Development Program's definitions of both young men (10 - 24 years) and youth (15 - 24 years).[33] Although data for young men aged 12 - 22 were available in the CJCP dataset, the use of this age range was justified owing to the increasingly younger age at puberty.[34,35] The indicators of sexual behaviour extracted for this analysis were numerically coded and are as given in Table 2.

The selection of the indicators follows the template of the Integrated Demographic Health Survey Data Descriptions. These indicators have also been used in other studies; however, some studies have added related indicators (e.g. time since last intercourse; age of the most recent sexual partner; consumption of alcohol during last sexual intercourse, and relationship with most recent partners).[25,36-38]

Data analysis

The study employed three levels of statistical analysis: univariate, bivariate and multivariate techniques. The univariate segment focused on respondents' sociodemographic characteristics using descriptive statistics (frequency distributions). The bivariate analysis was used to assess the characteristics associated with impregnating a girl. At the multivariate level, two models were formulated for the binary-coded dependent variable ('ever impregnated a girl'). Model 1 estimated the responsiveness of young men's involvement in teenage pregnancy to changes in the selected sociodemographic variables, while model 2 evaluated the influence of sociodemographic variables on young men's involvement in teenage pregnancies after controlling for selected sexual behaviour indices.

Ethical consideration

Existing secondary data on youth lifestyle in SA, as collated by the CJCP, were used in this study. The data were provided without any personal identifiers of respondents. The centre collects and disseminates data with regard to children and youth, parenting, substance abuse, early childhood development and school safety, and all international standards of data collection were duly employed.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The study includes data from young men aged 12 - 22 years from all SA provinces. Of the respondents, 70.7% were from the age group <18 years and 29.3% were from the age group >19 years (Table 1). The distributions by province were as follows: Gauteng - 19.0%; Limpopo - 7.0%; Free State - 8.5%; Mpumalanga - 7.6%; North West - 12.3%; Eastern Cape - 12.4%; Northern Cape - 5.4%; KwaZulu-Natal - 15.3%, and Western Cape - 12.4%.

Distributions by place of residence and race are also shown in Table 1. Almost all of the respondents (99.3%) had attended school, with 39.1% having completed Grade 11 - 12. Of the remaining respondents, 33.8% had completed Grade 9 - 10, and 27.1% had completed Grade 8 or lower. With regard to higher education, only 17.6% of the respondents had diploma, degree or postgraduate qualifications, 34.6% had certificates and 47.8% had no further formal education. The results also show that only 31.6% of the young men participated in religious activities, while 68.4% did not (Table 1).

Statistics regarding sexual behaviour show that 25.7% of the respondents had sex before the age of 15, 22.5% had impregnated at least one girl, and 26.7% had at least one biological child living with them (Table 2). An overwhelming proportion (93.2%) indicated that they have had two or more lifetime sexual partners. About one in five respondents (22.4%) rarely used condoms, 11.5% never used condoms and 66.1% reported using condoms frequently. Also, 16.5% of the respondents indicated that they had no knowledge of pregnancy prevention and 74.8% have not done HIV screening. With regard to contraceptive use, 16.5% of respondents indicated that they did not use any method of contraception during their last sexual activity, while approximately 71% claimed they or their partners used condoms and 12.1% said they used other contraceptive methods (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis

With regard to geographical distribution, the proportion of young men who have impregnated at least one girl was highest in the Eastern Cape (18.1%), followed by KwaZulu-Natal (15.7%), the Free State (13.5%) and Mpumalanga (13.1%) (Table 3). With regard to population group, the proportion was highest among Asian/Indian respondents (29.2%), followed by black African (13.2%), coloured (9.6%) and white (3.9%). Analysis of the variation in place of residence showed that 14.4% of respondents in metropolitan areas, 13.9% in rural areas and 11.2% in urban areas had impregnated a girl. Greater numbers of young men with tertiary qualifications (diplomas or degrees) had impregnated at least one girl (22.2%) compared with 12.4% and 5.6% of those without formal education and those with certificates, respectively. The proportion of respondents who reported having had two or more lifetime sexual partners and who have impregnated a girl is 13.9% (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

The binary logistic regression highlighted the degree of responsiveness of young men (who have impregnated at least one girl) through the selected sociodemographic factors and indices of sexual behaviour (Table 4). Two models were fitted: model 1 evaluated the influence of basic sociodemographic variables on the probability of a young man impregnating a girl, while model 2 predicted the probability of a young man impregnating a girl given certain sociodemographic factors while controlling for sexual behaviour indicators as covariate factors. Results from model 1 revealed that respondents who were 15 years or older were more likely to impregnate a girl compared with younger boys (odds ratio (OR) 3.81; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 2.88 - 5.04, p-value <0.05). Although there were no conspicuous variations among different population groups, the results did demonstrate a higher probability among black African, Asian/Indian and coloured respondents than among white respondents (Table 4).

With regard to education, respondents with higher qualifications (diploma/Bachelor degree/postgraduate qualification) were less likely to impregnate a girl (OR 0.44; 95% CI, 0.12 - 1.63) than those without education. The odds ratios among the respondents from urban and rural areas were higher than for men from metropolitan areas (Table 4). When covariates are controlled, the probability of young men impregnating a girl is lower in Mpumalanga and the Western Cape than in the other provinces. However, the results generally indicated that young black African, Asian/Indian and coloured men have higher odds ratios of impregnating girls compared with young white men. Young men with a sexual debut at 15 years or older had higher odds (47%) of impregnating a girl than those with an earlier sexual debut (OR 1.47; 95% CI, 0.53 - 14.77).

Respondents with two or more lifetime sexual partners were more likely to impregnate a girl (OR 2.51; 95% CI 0.43 - 14.77) than those with only one partner. The results also revealed that respondents who rarely used condoms were more likely to impregnate a girl (OR 1.66; 95% CI 0.37 - 7.38) than those who usually did use condoms (OR 0.37; 95% CI, 0.88 - 1.57) (Table 4). With regard to religious activity, the results indicate that young men who did not report participating in religious activities were more likely to impregnate a girl (OR 1.30; 95% CI, 0.76 - 0.22) compared with those who did participate in religious activities; however, this result is not statistically significant (p=0.337) (Table 4).

Discussion

The study investigated the sociodemographic characteristics of young men across all nine SA provinces who have impregnated at least one teenage girl. It also examined the prevalence of teenage pregnancy and teenage fathers in the respective provinces.

Despite several studies that have considered women's and families' sociodemographic factors as determinants of teenage pregnancy,[1,7,14] relatively little is known about the interplay between young men's sociodemographic characteristics and the incidence of teenage pregnancy in SA. Knowledge of the characteristics of young men who engage in sex with teenagers could prevent susceptibility of adolescent girls to unwanted sex and help to create a lasting solution to unplanned pregnancies in SA. Our study also highlights that despite numerous earlier initiatives to address the high rate of teenage pregnancy in SA, not considering young men's involvement may prevent a holistic approach to addressing this challenge. The use of the CJCP dataset, which is one of the most notable standardised nationally representative surveys in southern Africa, has allowed us to engage with the specifics of teenage pregnancy in the SA context. The overall result from this study could encourage the stakeholders to refine existing strategies towards reducing teenage pregnancy in the country.

Specifically, focusing on the sociodemographic characteristics and sexual indicators of young men involved in teenage pregnancies positioned the study as a paradigm shift from the general consideration of teenage pregnancy as a female problem.[39] The study also extends other studies in SA that focused on the determinants of teenage pregnancy[7,23] or adolescent fertility[7,24] by examining the characteristics of teenage fathers. In addition, the selection of sexual behaviour indices according to the template of the Integrated Demographic Health Survey Data Descriptions supports the appropriateness of the variables used in the analysis. There has not been a profound change in the age of first sexual activity (15.5 years) from the age reported in the 1990s (15.3 years, Eastern Cape;[1,7,14,40] 16.4 years, Gauteng and Western Cape[15]). Our findings on the young age at sexual debut corroborates earlier reports of early sexual debut among teenagers,[1,7,14,40] while the distribution according to population group may not necessarily support the high fertility among black teenage girls in SA as reported earlier;[1,7] considering older men's involvement in teenage pregnancies may also be a factor. In addition, the finding that a high proportion of young black African and Asian/Indian men are involved in teenage pregnancies could aid policy suggestions and directions.

Study limitations

The data used were based on self-reported information from respondents aged 12 - 22 years. Possible under-reporting of their sexual lifestyles or other behaviour may have affected the validity of the results. Also, the use of only one cross-sectional dataset limits the opportunity for comparisons and evaluation of the trends of young men's involvement in teenage pregnancy. However, the wide coverage of the survey and the empirical results in this study will contribute to policy and programme interventions.

Conclusion

The study showed that across all nine SA provinces a large proportion of young men are involved in teenage pregnancies. The lower likelihood for being involved in a teenage pregnancy observed among respondents with higher education and those that practise religious activities could be explored further to inform initiatives for curbing the teenage pregnancy rate. Although longitudinal trends in teenage pregnancies and young men's sexual behaviour were not analysed, the high prevalence of multiple sexual partnerships, as noticed in this study, could heighten youths' vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections if necessary actions are not taken. Therefore, it is recommended that appropriate awareness programmes are initiated among young men about the consequences of their sexual behaviour in an effort to reduce the incidence of teenage pregnancy in SA.

Acknowledgements. The authors appreciate the CJCP's permission to access the dataset for this study. The authors also thank the University of the Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, SA) for providing the resources and facilities that supported the preparation of the manuscript. EOA acknowledges the Covenant University (Ota, Nigeria) for providing the platform for academic collaboration with the University of the Witwatersrand. The support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CoE in Human Development. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Demography and Population Studies Programme, Schools of Public Health and Social Sciences, Faculties of Health Sciences and Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Author contributions. COO, EOA and NdW were responsible for conceptualisation and study design. NdW was responsible for data retrieval. EOA was responsible for data management, analysis, interpretation of results and writing the manuscript. COO and NdW reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Willan S. A Review of Teenage Pregnancy in South Africa - Experiences of Schooling, and Knowledge and Access to Sexual & Reproductive Health Services. Cape Town: Partners in Sexual Health, 2013. [ Links ]

2. Adeniyi OV, Aj ayi AI, Moyaki MG, Ter Goon D, Avramovic G, Lambert J. High rate of unplanned pregnancy in the context of integrated family planning and HIV care services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2942-z [ Links ]

3. Seutlwadi L, Peltzer K, Mchunu G, Tutshana BO. Contraceptive use and associated factors among South African youth (18-24 years): A population-based survey. S Afr J Obstet Gynaecol 2012;18(2):43-47. [ Links ]

4. Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Sanz S, et al. Impact of malaria at the end of pregnancy on infant mortality and morbidity. J Infect Dis 2011;203(5):691-699. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiq049 [ Links ]

5. Reddy P, Sewpaul R, Jonas K. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa: Reducing prevalence and lowering maternal mortality rates. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council, 2016. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-data/view/8117 (accessed 07 January 2018). [ Links ]

6. Statistics South Africa. Media Release: South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016, Key Indicators Report. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2017. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=9836 (accessed 07 January 2018). [ Links ]

7. Panday S, Makiwane M, Ranchod C, Letsoala T. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa: With a specific focus on school-going learners. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council and Department of Basic Education, 2009. [ Links ]

8. Department of Basic Education. Education for All (EFA): 2014 Country Progress Report. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education, 2014. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002316/231680e.pdf (accessed 5 December 2017). [ Links ]

9. Chigona A, Chetty R. Girls' education in South Africa: Special consideration to teen mothers as learners. J Edu Int Dev 2007;3(1):1-17. [ Links ]

10. IRIN Association. Teenage pregnancy figures cause alarm. http://www.irinnews.org/news/2007/03/06/teenage-pregnancy-figures-cause-alarm (accessed 24 July 2018). [ Links ]

11. Kyei KA. Teenage fertility in Vhembe District in Limpopo Province, how high is that? J Emerging Trends Econ Manag Sci 2012;3(2):134-140. [ Links ]

12. Ramulumo MR, Pitsoe VJ. Teenage pregnancy in South African schools: Challenges, trends and policy issues. Med J Soc Sci 2013;4(13):755-760. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n13p755 [ Links ]

13. Jewkes R, Morrell R, Christofides N. Empowering teenagers to prevent pregnancy: Lessons from South Africa. Cult Health Sex 2009;11(7):675-688. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050902846452 [ Links ]

14. Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 2001;52(5):733-744. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00177-5. [ Links ]

15. Richter L. A survey of reproductive health issues among urban black youth in South Africa. Final grant report. Society for Family Health-South Africa. Pretoria: Medical Research Council, 1996. [ Links ]

16. Slabbert AM. Identity, self-regulation, and gender inequality: Sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls and female sex workers in South Africa 'thesis1. Utrecht: Utrecht University, 2018. [ Links ]

17. Chandra-Mouli V, Svanemyr J, Amin A, et al. Twenty years after International Conference on Population and Development: Where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? J Adolesc Health 2015;56(1 Suppl):S1-S6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.015 [ Links ]

18. Arthur M, Earle A, Raub A, et al. Child marriage laws around the world: Minimum marriage age, legal exceptions, and gender disparities. J Women Polit Policy 2018;39(1):51-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477x.2017.1375786 [ Links ]

19. United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. New York: United Nations, 1979. [ Links ]

20. Peacock D, Levack A. The Men as Partners program in South Africa: Reaching men to end gender-based violence and promote sexual and reproductive health. Int J Mens Health 2004;3(3):173-188. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0303.173 [ Links ]

21. Bosch S. The communication approach of the loveLife HIV/AIDS prevention programme 'dissertation!. Potchefstroom: North-West University, 2009. [ Links ]

22. Thomas K. A better life for some: the loveLife campaign and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Agenda 2004;18(62):29-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2004.9676198 [ Links ]

23. Kara R, Maharaj P. Childbearing among young people in South Africa: Findings from the National Income Dynamics Study. S Afr J Demogr 2015;16(1):57-85. [ Links ]

24. Kaufman CE, De Wet T, Stadler J. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood in South Africa. Stud Fam Plann 2001;32(2):147-160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00147.x [ Links ]

25. Amoo EO, Igbinoba AO, Imhonopi D, et al. Trends, drivers and health risks of adolescent fatherhood in sub-Saharan Africa. SOCIOINT 2017 - 4th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 10 - 12 July 2017. [ Links ]

26. Loaiza E, Liang M. Adolescent pregnancy: A review of the evidence. New York: United Nations Population Fund, 2013. [ Links ]

27. Atkinson D. Rural-urban linkages: South Africa case study. Working paper series No. 125, 2014. Working Group: Development with Territorial Cohesion. Territorial Cohesion for Development Program. Santiago: RIMISP, 2014. [ Links ]

28. Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER. The importance of place of residence: Examining health in rural and nonrural areas. Am J Public Health 2004;94(10):1682-1686. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.10.1682 [ Links ]

29. Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart G. Metropolitan, urban, and rural commuting areas: Toward a better depiction of the United States settlement system. Urban Geogr 1999;20(8):727-748. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.20.8.727 [ Links ]

30. Burgess EW. The growth of the city: An introduction to a research project. In: Marzluff JM, Shulenberger E, Endlicher W, et al., eds. Urban Ecology. An International Perspective on the Interaction Between Humans and Nature. New York: Springer Science + Bussiness Media, 2008:71-78. [ Links ]

31. Soja EW. Postmetropolis: Critical studies of cities and regions. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000. [ Links ]

32. Tajbakhsh K. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions [book review]. Urban Stud 2001;38(9):1620-1622. [ Links ]

33. United Nations Development Programme. UNDP Youth Strategy 2014-2017. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Democratic%20Governance/Youth/UNDP_Youth-Strategy-2014-17_Web.pdf (accessed 24 July 2018). [ Links ]

34. Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, Moilanen KL. Adolescent sexuality: Behavior and meaning. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. Malden: Blackwell, 2003:371-392. [ Links ]

35. Jones LL, Griffiths PL, Norris SA, Pettifor JM, Cameron N. Is puberty starting earlier in urban South Africa? Am J Hum Biol 2009;21(3):395-397. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20868 [ Links ]

36. Burton P, Leoschut L. Dealing with school violence in South Africa. Results of the 2012 National School Violence Study. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention, 2013. [ Links ]

37. Doyle AM, Mavedzenge SN, Plummer ML, Ross DA. The sexual behaviour of adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: Patterns and trends from national surveys. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17(7):796-807. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03005.x [ Links ]

38. National Population Commission. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013: Preliminary Report. Abuja: National Population Commission, 2013. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR293/FR293.pdf (accessed 29 July 2017). [ Links ]

39. Thornberry TP, Wei EH, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Dyke J. Teenage fatherhood and delinquent behavior. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2000. [ Links ]

40. Richter L, Mabaso M, Ramjith J, Norris SA. Early sexual debut: Voluntary or coerced? Evidence from longitudinal data in South Africa - the Birth to Twenty Plus study. S Afr Med J 2015;105(4):304-307. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.8925 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

E O Amoo

emma.amoo@covenantuniversity.edu.ng

Accepted 4 June 2018