Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Child Health

On-line version ISSN 1999-7671

Print version ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.12 n.2 Pretoria Apr./Jun. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajch.2018.v12i2.1262

RESEARCH

Monitoring well-baby visits in primary healthcare facilities in a middle-income country

D G SokhelaI; M N SibiyaII; N S GweleIII

ID Nursing; Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Durban University of Technology, South Africa

IID Tech Nursing; Office of the Dean, Faculty of Health Sciences, Durban University of Technology, South Africa

IIIPhD; Vice Chancellor's Office, Durban University of Technology, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Globally, child health services are a priority, but are most acutely felt in underdeveloped and developing countries. Most of the children who live in such countries die from a disease or combination of diseases that could easily have been prevented through immunisations, or treated at a primary healthcare level. Undernutrition contributes to over a third of these deaths. Preventive measures are important to proactively prevent such disease and mortality burdens. Well-baby visits are for babies who come to the clinic for preventive and promotive health, and who are not sick. One of the goals in the National Core Standards is to reduce waiting time in health establishments. However, it is imperative that all necessary assessments are conducted during a well-baby visit. The Road to Health booklet (RtHB) contains the baby's health record, and is issued to all caregivers, usually on discharge post-delivery. It also contains lists of appropriate assessments that should be performed during each well-baby visit according to age, including immunisations and health promotion messages for caregivers. In South Africa, infant morbidity and mortality rates are decreasing very slowly, requiring effective use of the RtHB to address important applied and research problems.

OBJECTIVE. To investigate how 'well babies' were monitored in primary healthcare facilities.

METHODS. A descriptive quantitative cross-sectional survey design was used for retrospective review of 300 babies' RtHBs, using a checklist developed directly from the assessment page of this booklet. The clinical microsystem model was used to guide the study. Data were analysed using SPSS version 22.0.

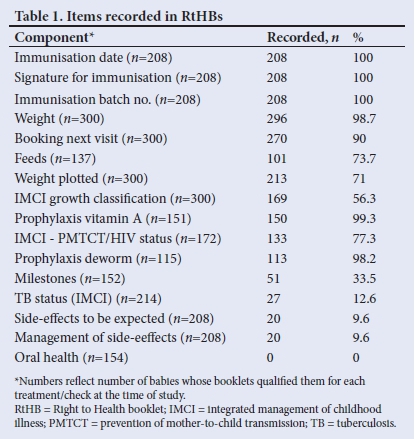

RESULTS. Babies were shown to have been immunised in 100% of records, while discussion of side-effects and the management thereof were only recorded in 9.7% (n=20) charts. Records indicated that 98.7% (n=296) of babies were weighed, but only 71% (n=213) of weights were 'plotted' and 56.3% (n=169) classified according to the integrated management of childhood illnesses norms.

CONCLUSION. Based on the findings, this research was able to make a contribution to the body of knowledge about baby monitoring practices in primary healthcare settings.

In most middle- and low-income countries, especially in rural areas, child health services are a priority, as child morbidity and mortality remain high; children still die from vaccine-preventable diseases, malnutrition and HIV/AIDS-related illnesses. In South Africa (SA), infant morbidity and mortality rates are decreasing very slowly.1 The SA democratic government has committed itself to the promotion of health through prevention and education strategies in primary healthcare (PHC) clinics.2 To fulfil this mandate, the government has prioritised healthcare for children <6 years of age, and healthcare for pregnant and lactating women is provided for free (this policy has since been extended to all PHC users. Furthermore, of the sustainable development goals (SDGs), numbers 1 and 2 aim to reduce poverty and hunger, which remain a challenge in developing countries. Children <5 years old are the worst affected, with inadequate height-for-age scores (stunted growth). Poor nutrition causes deaths in these children.3 Well-baby visits have been implemented for babies who come to the clinic for preventive and promotive healthcare, such as weighing, prophylactic treatments and immunisations.

The Road to Health booklet (RtHB) has been in use since 2011. It is a communication tool between caregivers and healthcare providers, and a health management and educational tool. It contains the revised immunisation schedule, as well as additional health promotion messages.4 It replaced the Road to Health chart, which was smaller, and difficult to plot weight in. The RtHB lists the assessments to be performed at well-baby visits that are appropriate for age, for timeous and appropriate interventions, as well as a schedule of immunisations that must be given. Despite these provisions, there has still been little improvement in child morbidity and mortality. In well-baby clinic visits, care is delivered expeditiously, as this is one of the strategies in place to prevent unnecessary delays and decongest the facility.

Observation of well-baby clinical encounters in PHC facilities in a large SA city indicated that although health professionals were adequately trained and facilities well equipped, routine examination procedures were poorly performed, and there was insufficient growth monitoring and management.5 Recording in the RtHBs indicated that not all children were weighed, or their weight correctly plotted and correctly interpreted. Immunisations were offered to all eligible babies, while developmental milestones were asked about in only a small percentage of children. Health promotion and prevention activities, such as growth monitoring, immunisation and developmental assessment, were not performed adequately, even though the healthcare providers had all the necessary means available.

The clinical microsystems model,6 the smallest replicable unit of healthcare, guided the study. It is characterised by five elements: (i) purpose: why the clinical microsystem exists, which in this case is to provide expeditious service; (ii) patients: the people served by the clinical microsystem, well babies and children in this study; (iii) professionals: the staff working in the microsystem; (iv) processes: how care and services are delivered to meet patients' needs - the care-giving support processes that the clinical microsystem uses to provide care and services; and (v) the patterns that characterise the clinical microsystem's functioning. For the purposes of this article, the elements 'patients' and 'processes' are discussed. A PHC facility is a clinical microsystem within the administration it is under, and each different service rendered within the facility, such as, in this article, the 'well-baby clinic, forms a clinical microsystem within the larger clinic. Good practices in one microsystem can be replicated in other microsystems within the clinic, making their work run more smoothly. The aim of the study was to determine how thoroughly healthcare providers in the well-baby clinic monitor babies.

Methods

Design

A descriptive cross-sectional design was used to conduct the study in randomly selected PHC facilities in eThekwini district in KwaZulu-Natal Province, SA. There are 8 community health centres and 102 PHC facilities in the district. In addition to these, 28 mobile units service the hard-to-reach rural areas.

Sampling

Two-stage sampling was used: of facilities, and of caregivers. A sample of 20 (32%) of 62 facilities, with an average of 190 users of the well-baby clinical microsystem a month, was randomly chosen using a fishbowl sampling technique. The names of clinics were written on pieces of paper, put in a bowl and blindly picked out. This technique afforded each facility an equal opportunity to be included in the sample. Thereafter, a systematic sample was taken, where every fifth parent or primary caregiver and legal guardian was asked for the use of the RtHB. Only parents or legal guardians could consent to the study. Naing's7 sample size calculator was used to determine an adequate sample size of facilities, and Daniel's8 formula was used to calculate the sample size of RtHBs. It was assumed that 50% of caregivers would be carrying the RtHBs. In this study, a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of .05 was used to calculate the sample size. The sample size calculator produced a total of 285 observations in the 20 facilities within the study, which was rounded off to 300 record reviews of RtHBs, equalling 15 reviews conducted in each facility.

The RtHBs of 300 babies and children were therefore reviewed, in order to determine whether assessments had been captured. Records of babies and children brought in by caregivers who were not their legal guardians were excluded.

Data collection

A 16-item checklist, developed directly from items in the RtHB, was used to determine the recording of assessments conducted to monitor well babies. The items were: weight; weight plotted; integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) classification of growth, prevention of mother-to-child transmission/HIV status and tuberculosis (TB) status; feeds; date; batch number of immunisation given; signature of the nurse who administered the immunisation; side-effects to be expected; management of side-effects; prophylaxis vitamin A and deworming; milestones; oral health; and next visit. This ensured consistency and correct documentation, and enabled the researcher to go through a large number of records quickly without missing any items. A 'yes' or 'no' indicated whether the item had been recorded, and in some cases, 'N/A' indicated due to the baby's age. The researcher sat in a private room for 10 minutes while reviewing the card and completing the checklist. The researcher visited each clinic every day until the required number of RtHBs had been reviewed.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, USA). Descriptive statistics illustrating spread, such as proportions, frequencies, ranges and central tendencies such as means, modes medians and standard deviations were computed where appropriate. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data, such as the children's demographic data, and their assessments.

Ethical approval

The researcher obtained approval from the Durban University of Technology Ethics and Higher Degrees Committee (ref. no. REC 33/13), as well as from gatekeepers of PHC facilities. Caregivers signed informed consent forms while waiting in the queue for the service. Participant codes were used to maintain confidentiality.

Results

A total of 300 baby records was reviewed. The age range of the babies was 0 - 59 months.

Patients

Demographic data on age and gender were collected. The mean age of the children was 2.49 months (standard deviation 1.957). Records indicated that there were 51% (n=153) females and 49% (n=147) males.

Processes: Assessments in the well-baby clinic

Analysis of 300 RtHBs found that 208 babies and children had attended the clinic for immunisation, and all had had the immunisation date, batch number and signature of the nurse administering it recorded in 100% (n=208) of the charts. Records indicated that 98.7% (n=296) of babies were weighed, but only 71% (n=213) of the weights were 'plotted' in the RtHBs. Depending on the reading of the graph, weights are used to classify growth according to IMCI norms. Classification of growth was recorded in 56.3% (n=169) of the charts. There is a requirement that the HIV status or exposure to HIV from the mother is established from 3 days to 10 weeks of age, and at 6-monthly intervals thereafter until 18 months of age, and then whenever necessary. There were 172 records in which this was expected to have been recorded; however, records indicated that 'PMTCT [prevention of mother-to-child transmission]/HIV status' was only recorded in 77.3% (n=133) of charts. Healthcare providers were supposed to ask about feeding options (exclusive breast or bottle feeding, or mixed feeding) from caregivers of babies that were from birth to 6 months old. Of 137 baby records, feeding was recorded as having been asked about in 73.7% (n=101) of baby records. Vitamin A and deworm prophylactic treatment is routinely given to babies from the age of 6 months, and every 6 months until the child is 60 months old. Baby charts indicated that 'vitamin A prophylaxis' was given in 99.3% (n=150) of 151 babies and children, and 'deworm prophylaxis' was recorded to have been given in 98.2% (n=113) of 115 babies and children. These included babies and children who were due for the prophylaxis according to age, and those who were catching up because of missing doses at the due age. Caregivers are given a date to bring babies for the next visit, and baby records indicated that 'booklet next visit' was recorded in 90% (n=270) of baby records.

However, the record review indicated the following elements as the least often recorded. According to the RtHB, milestones are supposed to be assessed on babies at 6 weeks, 14 weeks, 6 months, 9 months, 18 months, 36 months and 60 months of age, but in this study the milestones were recorded in only 33.5% (n=51) of 152 records of children who were of the correct age for the milestones to be assessed. TB status is supposed to be assessed from the age of 14 weeks, but it was found to be recorded in 12.6% (n=27) of the 214 records. Side-effects to immunisation and the management thereof are to be discussed with caregivers at every immunisation session, either by providing the information or checking previous knowledge. This was found to be recorded as having been done in 9.6% (n=20) of the 208 babies' charts. Oral health should have been assessed and recorded in 154 charts; however, it was observed that it was not recorded in 100% of these charts (Table 1).

Discussion

Babies and children assessed in this clinical microsystem were between the ages of 0 and 59 months. Administration of immunisation, dates and batch numbers of vaccines were adequately documented. This indicates the efficiency of immunisation services in the process of the clinical microsystem. If the child becomes sick within 72 hours of receiving an immunisation, an adverse event is recorded. This enables all vaccines with the same batch number to be checked, and all babies who received immunisations from that batch to be monitored for signs of side-effects.

Regular weighing and recording of babies assists in early detection of malnutrition, which may prevent vulnerability to diseases and death, and allow early intervention to be implemented.9 Deviation from the pattern of child growth indicates that the child might have an illness, or alternatively, lack nutrients in the body.10The classification of growth directs the health worker to the relevant/suitable intervention for the child's nutritional status. It was envisaged that the RtHB would increase the likelihood of interpreting weight and classifying growth.11 The SA government in 2011 declared support for the promotion of breastfeeding in all health establishments in the Tshwane Declaration'12 as a strategy to curb malnutrition.

Currently, HIV and TB are major health problems in SA. In order to improve maternal and child health, HIV and TB services were integrated into maternal and child healthcare in 2009.13Good progress has been made in PMTCT, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing at birth and prophylactic antiretroviral therapy (ART), as well as lifelong ART for HIV-positive pregnant women, irrespective of CD4 count.

The timing of vitamin A administration was designed to coincide with immunisation, to minimise clinic visits for children 6 - 59 months old.14 Vitamin A reduces deaths from measles and diarrhoea, and the overall mortality of children >5 years of age. Government has mandated the fortification of staple foods such as maize meal and wheat flour, and those products containing 90% of these foods, such as bread, with vitamin A.15

Worm infestation contributes to anaemia and poor growth. In Nigeria, after deworming with a single dose of albendazole tablet 400 mg, the number of children with normal haemoglobin increased to 57.3%.16 After 2 years of treatment, there was significant weight gain in children.

Developmental milestones are normally achieved at different stages of growth and development, at a pace unique to each baby. However, if these are not assessed, it could affect the baby's entire future. 17

Children can suffer from tooth decay from a very young age, and so their teeth need to be cared for from as early as 1 year of age. Early childhood caries is a challenge throughout the world, as it may result in loss of teeth if not checked.18

Recommendations

Good practices found in this clinical microsystem should be replicated in other clinical microsystems within the facility. Healthcare providers need to be reminded of or given in-service training on the use of the RtHB. Emphasis has to be placed on the importance of well babies' assessments, to improve child morbidity and mortality, which remain a challenge in SA. If healthcare providers were to carry the assessments out appropriately, the country could be well on the way to overcoming some of the obstacles to reaching the SDGs. Improved and effective communication with caregivers about side-effects to look out for following immunisation is recommended, as this would minimise hospital admissions and deaths. Discussions on how some of these could be managed at home, and which ones to bring the child back to the clinic for, should be seen as vital. Supportive supervision by clinic managers may assist in identifying staff development requirements regarding child assessments and the recording thereof. Assessment of milestones is very important for early intervention and referral to relevant agents where required, to improve the lives of children.

Limitations

The RtHBs of babies and children brought in by other people other than biological parents and legal guardians were not reviewed. Crucial information might have been missed from these records.

Conclusion

Well-baby care is an important component of PHC, as all assessments are critical, because the child's future may depend on them. Abnormalities might not be detected if these aspects of the RtHB are not completed, recorded and acted upon, which could result in major problems later. Good recording practices are crucial for continuity of care, especially for babies and children, as they are still growing and some abnormalities can still be corrected.

Acknowledgements. I thank the university for the opportunity to study, the supervisors for their support during the study, and SANTRUST for the research methodology training and guidance.

Author contributions. The first author (DGS) was the primary researcher, MNS the supervisor and NSG the co-supervisor of the project.

Funding. The university research and post-graduate office provided funding for the study.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. Young Child Survival and Development. New York: UNICEF, 2011. http://www.unicef.org/childsurvival/ (accessed 12 March 2015). [ Links ]

2. African National Congress. The National Health Plan for South Africa. Pretoria: ANC, 1994. [ Links ]

3. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Washington DC: UN, 2015. [ Links ]

4. Republic of South Africa. Minister Botha Launches Road to Health Booklet. Pretoria: Government of South Africa, 2011. http://www.gov.za/minister-botha-launches-road-health-booklet (accessed 5 December 2015). [ Links ]

5. Thandrayen K, Saloojee H. Quality of care offered to children attending primary healthcare clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa. S Afr J Child Health 2010; 4(3):73-77. [ Links ]

6. Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Godfrey MM. Value by Design: Developing Clinical Microsystems to achieve Organizational Excellence. London: Jossey-Bass, 2011. [ Links ]

7. Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BN. Sample Size Calculator for Prevalence Studies. 2006. http://www.kck.usm.my/ppsg/stats_resources.htmNaing (accessed 12 March 2013). [ Links ]

8. Daniel WW. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences. 7th edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999 . [ Links ]

9. Brink HI, van Rensburg G, van der Walt C. Fundamentals of Research Methodology for Health Care Professionals. Cape Town: Juta, 2012. [ Links ]

10. Ezekiel J, Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA 2000;283(20):2701-2711. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.20.2701 [ Links ]

11. KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health. District Health Plan 2014/2015. EThekwini District. Durban: KZN DoH, 2013. [ Links ]

12. World Health Organization, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, Republic of South Africa. Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses. Geneva: WHO, UNICEF, 2014. [ Links ]

13. Cloete I, Daniels L, Jordaan J, Derbyshire C, Volmink L, Schubl C. Knowledge and perceptions of nursing staff on the new Road to Health Booklet growth charts in primary healthcare clinics in the Tygerberg subdistrict of the Cape Town metropole district. S Afr J Clin Nutr 2013;26(3):141-146. http://academic.sun.ac.za/Health/Media_Review/2013/18Nov13/files/Knowlege.pdf (accessed March 2015). [ Links ]

14. Norris SA, Griffiths P, Pettifor JM, Dunger DB, Cameron N. Implications of adopting the WHO 2006 Child Growth Standards: Case study from urban South Africa, the Birth to Twenty cohort. Ann Hum Biol 2008;36(1):21-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460802620694 [ Links ]

15. National Department of Health, South Africa. Infant and Young Child Feeding Policy. Pretoria: NDoH, 2012. [ Links ]

16. National Department of Health, South Africa Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Children. 2nd edition. Pretoria: NDoH, 2010. [ Links ]

17. Sufiyan B, Sabita K, Mande AT. Evaluation of effectiveness of deworming and participatory hygiene education strategy in controlling anaemia among children age 6 - 16 years in Gadagau community, Giwa LGA, Kaduna, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2011;10(1):6-12. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.76561 [ Links ]

18. Awasthi S, Peto R, Read S, et al. Population deworming every 6 months with albendazole in 1 million pre-school children in North India: DEVTA, a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2013;381(9876):1478-1486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62126-6 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

D G Sokhela

(dudus@dut.ac.za

Accepted 21 December 2017