Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Child Health

On-line version ISSN 1999-7671

Print version ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.11 n.1 Pretoria Jan./Mar. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajch.2017.v11i1.1253

RESEARCH

doi:10.7196/sajch.2017.v11i1.1253

Parental satisfaction in the traditional system of neonatal intensive care unit services in a public sector hospital in North India

V SankarI; P BatraII; M SarohaIII; J SadizaIV

IMBBS; Department of Paediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India

IIMD, FACEE; Department of Paediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India

IIIMD; Department of Paediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India

IVMPhil; Department of Paediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Traditional systems of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) care predispose parents to increased levels of stress and anxiety due to parental separation from their infant. Parental satisfaction, an indicator of the quality of care, is significantly compromised during prolonged NICU stay. The research is limited in developing countries.

OBJECTIVES. To assess the parental satisfaction with traditional systems of NICU care in a public sector hospital and to identify the areas that need improvement and can be worked upon.

METHODS. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to interview the parents of the neonates on the day of discharge. Fifteen questions were categorised into four domains, namely interpersonal relationships with staff, parents' involvement, staff competence and services offered by the health system. Parental satisfaction level was marked on a three-point Likert scale, 0 corresponding to highly dissatisfied, and 2 to completely satisfied for each of the 15 questions.

RESULTS. Out of 100 patients interviewed, communication was the chief determinant of their satisfaction. Parents expressed fair satisfaction levels with regard to the emotional support and encouragement received, but discontent at being unable to look after their own baby and breastfeed the baby. They were satisfied with the competence of the staff.

CONCLUSION. The traditional system of NICU care was not satisfying for the parents in many aspects and changes in the form of family-centred care should be tried for greater parental satisfaction.

Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission is a time of significant stress for the parents.[1] The mother is at increased risk of postpartum depression, both during the neonate's hospitalisation and in the post-discharge period. The major concerns of NICU parents during this stressful time are their informational needs, their grief response, their parent-child role development, stress, and coping and social support.[2] In most hospitals, the traditional system of NICU care is followed, where babies are admitted to NICU under the supervision of doctors and nurses only, without much parental involvement. The parents are shown the baby once a day and updated regarding their baby's condition during counselling sessions. The existing system forbids the presence of parents during the time of clinical rounds. Adding to the distress is the inability of the mother to breastfeed directly, as the expressed breastmilk is fed to the baby by nursing staff as per its need.[3] The steady rise in the number of NICU admissions necessitates a quantitative as well as a qualitative improvement in the services offered by NICUs in tertiary hospitals in a developing country. Higher parental satisfaction and lower stress levels among parents are major determinants in the prompt recovery of the neonate.[4,5] The purpose of these improvements would be for the parents to understand the situation and be able to cope with it successfully. Studies have identified 11 dimensions of care as important to parents whose infants receive neonatal intensive care: assurance, caring, communication, consistent information, education, environment, follow-up care, pain management, participation, proximity, and support.[6] Russell et al.[7]found that the provision of information, support, and an increase in their involvement in the care of their baby were highlighted by parents as important in their experience of care, and thus contributed to greater satisfaction.

Little is known about the satisfaction level of parents of neonates requiring intensive care in developing countries.[8,9] Therefore we planned this study with the objective of assessing parental satisfaction with the traditional system of NICU care in a public sector hospital in North India, and of identifying the areas that need improvement and can be worked upon.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out in the Division of Neonatology in the Department of Paediatrics of a tertiary care teaching hospital between April and July 2015, after obtaining clearance from the institutional ethical committee. Parents of 100 late-preterm and term neonates (>34 completed weeks of gestation) admitted to NICU for more than 7 days were enrolled after written informed consent had been obtained. The parents of neonates born with major congenital malformations, with mothers who were HIV-or hepatitis B-positive, or who had any other chronic illness, were excluded from the study.

Detailed methodology

A semi-structured questionnaire was used to interview the parents of the neonates, preferably the mothers, on the day of discharge. At the time of interview, the babies were either currently in the NICU, or they were with the mothers in the postnatal unit or in a transitional (lying-in) ward, where they were being taken care of by the mothers, under the constant supervision of nursing staff and doctors. The questionnaire included demographic details such as educational status, socioeconomic status and parity of the mother, along with the neonate's gestational age, birth weight, age at the time of survey and detailed diagnoses. For the assessment of satisfaction level, it included 15 questions regarding the experience of the neonatal care that was provided to their babies during admission. These questions were categorised into four domains, namely interpersonal relationships with staff, parental involvement, staff competence and services offered by the health system. Parents' satisfaction level was marked on a three-point Likert scale. The satisfaction level was scored as 0, 1 or 2, with 0 corresponding to highly dissatisfied, and 2 to completely satisfied for each of the 15 questions. Open suggestions for improvement in the system were also asked for and recorded if the score was either 0 or 1. The questionnaire took ~25 minutes to complete. In preparation of the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted for 4 days followed by a role-play with the clinical psychologist, and was later modified based on the comments and suggestions.

Statistical analysis

Responses by the parents were analysed using SPSS software 20.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Descriptive statistics were applied for data analysis, with the open-ended responses being described using percentages. Factors affecting the satisfaction level were compared using a t-test.

Results

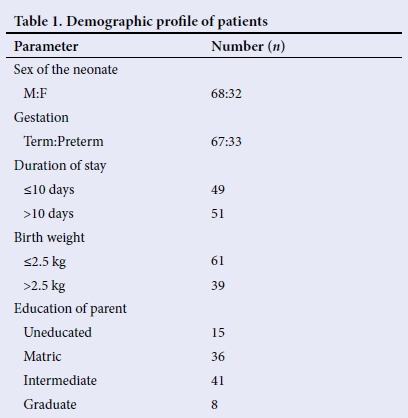

We interviewed 100 parents for the study without any parent refusing an interview. The demographic data for parents and their neonates are depicted in Table 1. The mean duration of stay of a neonate at the time of interview was 11 days. The number of parents with the satisfaction level achieved in each domain as graded on the Likert scale is depicted in Table 2.

Responses by the parents

Interpersonal relationships with staff

• Communication: A large fraction of the parents mentioned communication as the chief determinant of their satisfaction. A little over half of the parents expressed their dissatisfaction with the communication with caregivers. Nearly one-third of the parents felt that doctors took very little time to answer their queries, and this increased their apprehension. Furthermore, some parents stated that doctors ought to talk to them politely, as doing so would relieve much of their anxiety. Almost half of the parents stated that they felt the information provided to them by the caregivers was inadequate. They felt, however, that nurses were more easily accessible than doctors for obtaining information and added that they were more considerate towards their circumstances. A little over a quarter (n=27) of the parents suggested that the hospital should provide them with a leaflet at the time of discharge graphically representing the danger signs for them to look out for in their babies.

• Emotional support: Parents expressed fair satisfaction levels with regard to the emotional support and encouragement received. They expressed contentment at having received encouragement and praise from the nurses. Concurrently, having identified doctors as a superior authority, many voiced their desire for doctors to be more supportive. This, they felt, would conceivably improve their confidence.

Parental involvement

• Direct involvement in patient care: Over two-fifths of the parents expressed their dismay at being unable to look after their own baby. Parents mostly expressed concern over the long duration of the hospital stay and their separation from their baby, adding that they were worried about the baby not recognising them or responding to them.

• Expressing breastmilk: A little over one-third of the mothers expressed discontent over their inability to breastfeed the baby. The existing system of expressing breastmilk into a container bothered many mothers. While for some the reason was uncertainty as to whether the milk was actually fed to the baby, others were concerned about the hygiene of such a practice. Over one-third of mothers (n=36) described how they felt under considerable pressure to produce breastmilk because of frequent reproach by the nurses, and suggested that they should instead be reassuring in such circumstances.

Competence of the staff

Most parents expressed satisfaction with the experience and competence of the neonatal staff. They said that the counselling session held every afternoon reassured them of the skills of the doctors, and added that they were glad the doctors were doing their best. However, a few parents mentioned that they often felt overburdened by the vast amount of complex information the doctors provided them with, and suggested that it be simplified.

Services offered by the health system

Parents showed dissatisfaction with this aspect of neonatal intensive care. This included blood and some medicines that had to be arranged by relatives, often straining their financial situation. The most common cause was their inability to afford the medicines required. The majority of medications are provided by the government and the institute, and only rarely may parents be asked for something, in the case of non-availability. Some parents also commented that difficulties were faced when they were asked to arrange blood for a second time. They added that blood should be made available by the hospital if required more than once. Alternatively, some parents suggested that the hospital ask them to arrange blood beforehand, stating that it was difficult for them to arrange it at the time of need. Parents also felt the need for a health insurance scheme for neonates, which is lacking in the present system.

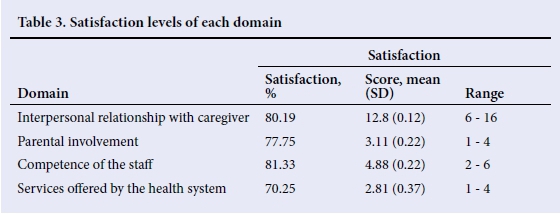

Table 3 shows the mean satisfaction level of parents in each domain. The highest satisfaction levels were observed in interpersonal relationships with caregivers and the competence of staff, while parents were most dissatisfied with the services offered by the health system.

The satisfaction level of parents in relation to gender, gestational age, birth weight and the educational status of parents were comparable. With an increasing duration of hospital stay, a gradual increase in satisfaction level with respect to parental involvement was observed, with a slight decline in interpersonal relationship satisfaction, although it did not reach statistically significant levels.

Discussion

Parents face a number of challenges when their newborn infant is admitted for NICU care. These include the loss of work hours, separation from the baby, the inability to feed the baby and the financial burden, to name a few. An overburdened public sector hospital in a developing country lacks the support systems required to take care of these concerns, resulting in dissatisfied parents and poor neonatal care. An assessment of the satisfaction level of parents is an initial step in identifying the areas that require intervention so that parents are more satisfied with the healthcare system and can cope more successfully. Our study concluded that parents showed most dissatisfaction with the services offered by the healthcare system, and with parental involvement in care of the baby. Both these aspects need to be addressed for better outcomes for sick and preterm newborns.

Establishing effective communication with the parents and providing them with adequate information about their infants and the required care can result in increased satisfaction (p<0.01), as is evident from the study conducted by Weiss et al.[10] A study by Ranchod et al. [6] concluded that increased perinatal counseling allowed parents to take a more active decision-making role and invariably led to higher rates of parental satisfaction with neonatal care in intensive care units. Constraints on staff limit the time available for extensive parent counselling by physicians, leaving parents to depend on nurses to help explain their infant's status.[8] Reis et al.[11]report that interaction with nurses and verbal and written information regarding the condition of infants were essential, and of course the method of communication was also of significance. It has also been observed that excessive information can lead to parental confusion, which therefore can decrease confidence in healthcare systems, increase anxiety and eventually decrease parental satisfaction.[12,13]

Family-centred care (FCC) is an alternative system of NICU care that can provide an answer to these problems faced by parents, as under this system they are actively involved in the management of the baby, under the strict supervision of nursing staff and doctors. Encouraging parents to spend time with their infants and actively participate in the care process can facilitate the development of parental roles and increase the satisfaction rate.[14] Bakewell-Sachs and Gennaro[15] have indicated that active maternal involvement in neonatal care and mother-infant contact (e.g. touching the baby) increases maternal confidence in taking care of the infant after discharge, and consequently lead to higher maternal satisfaction. Integrated notes can be kept by the side of the baby's cot so that information is accessible to parents in clear language. Bastani et al.[16]compared FCC with controls in a randomised trial and found that mothers in the FCC group were more satisfied with the aspects of information and participation in care. The number of neonatal readmissions was lower in the FCC group compared with the control group, and the mean duration of hospitalisation was shorter compared with the control group (6.96 v. 12.96 days; ƒx0.001). Ortenstrand et al.[17] found a 5-day reduction in the duration of hospitalisation for preterm infants, and reported that parental involvement can directly affect the stability and morbidity of the infants. Parents who spend more time with their infants have more opportunities for perceiving the signs of infants' discomfort and their other needs; consequently, they function better in comparison with nurses who are responsible for the care of multiple infants.[18]

Parental satisfaction in a single-family room NICU was higher in comparison with the traditional open-bay NICU system. The single-family room environment seemed more conducive to the provision of FCC.[19,20]

In our study, most of the patients were of low and lower-middle socioeconomic status, and were semi-skilled or unskilled workers with minimal family support. A study conducted in private sector hospitals may result in different levels of satisfaction and different responses. As expressed by a couple of parents, feeling intimidated by the doctors and the sophistication of the NICU may have resulted in lower levels of satisfaction.

There is a paucity of data from India, and ours is an initial attempt to rectify this. Open-ended questions were used and suggestions were also invited for improvement. A possible limitation of this study is 'gratitude bias', which was partly solved as the interviewer was not directly involved in the care of the baby. Also, the interviews were conducted on the day of discharge so that parents would not feel reluctant to give critical comments. On the other hand, this could have led to higher satisfaction levels since their baby's health had improved. If the interviews had been conducted when the baby was sick, this might have led to lower satisfaction levels.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable information regarding the various factors considered most important by parents in determining their overall satisfaction with their experiences of neonatal intensive care. Although a small fraction of parents reported satisfaction with the care being provided, most parents felt that there was significant scope for improvement in various aspects. Many parents were forthcoming with suggestions which, if implemented, could perhaps result in significantly higher levels of satisfaction. Improved parental satisfaction with care, and the potential for enhanced FCC, need to be considered in decisions made regarding the configuration of NICU facilities in the future.

REFERENCES

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Behrman RE, Butler AS, eds. Preterm birth: Cuses, consequences, and prevention. Washington: National Academies Press (US), 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.17226/11622 [ Links ]

2. Fishering R, Broeder JL, Donze A. A qualitative study: NICU nurses as NICU parents. Adv Neonatal Care 2016;16(1):74-86. http://dx.doi.org/110.1097/anc.0000000000000221 [ Links ]

3. Chourasia N, Surianarayanan P, Adhisivam B, Vishnu Bhat B. NICU admissions and maternal stress levels. Indian J Pediatr 2013;80(5):380-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12098-012-0921-7 [ Links ]

4. Bastani F, Abadi TA, Haghani H. Effect of family-centred care on improving parental satisfaction and reducing readmission among premature infants: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9(1):SC04-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2015/10356.5444 [ Links ]

5. Blackington SM, Mclauchlan T. Continuous quality improvement in the neonatal intensive care unit: Evaluating parent satisfaction. J Nurs Care Qual 1995;9(4):78-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001786-199507000-00011 [ Links ]

6. Ranchod T, Ballot DE, Martinez AM, Cory BJ, Davies VA, Partridge JC. Parental perception of neonatal intensive care in public sector hospitals in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2004;94(11):913-916. [ Links ]

7. Wainer S, Khuzwayo H. Attitudes of mothers, doctors, and nurses toward neonatal intensive care in a developing society. Pediatrics 1993;91(6):1171-1175. [ Links ]

8. Russell G, Sawyer A, Rabe H, et al. Parents' views on care of their very premature babies in neonatal intensive care units: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr 2014;14,230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-230 [ Links ]

9. Franck LS, Oulton K, Nderitu S et al. Parent involvement in pain management for NICU infants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2011;128(3):510-518. http://dx.doi.org/110.1542/peds.2011-0272 [ Links ]

10. Weiss S, Goldlust E, Vaucher YE. Improving parent satisfaction: An intervention to increase neonatal parent-provider communication. J Perinatol 2010;30(6):425-430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.163 [ Links ]

11. Reis MD, Scott SD, Rempel GR. Including parents in the evaluation of clinical microsystems in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care 2009;9:174-179. http://dx.doi.org/110.1097/anc.0b013e3181afab3c [ Links ]

12. Lupton D, Fenwick J. 'They've forgotten that I'm the mum': Constructing and practicing motherhood in special care nurseries. Soc Sci Med 2001;53(8):1011-1021. http://dx.doi.org/110.1016/s0277-9536(00)00396-8 [ Links ]

13. Conner JM, Nelson EC. Neonatal intensive care: Satisfaction measured from a parent's perspective. Pediatrics 1999;103(Suppl 1):S336-S349. [ Links ]

14. Wielenga JM, Smit bJ, Unk LK. How satisfied are parents supported by nurses with the NIDCAP model of care for their preterm infant? J Nurs Care Qual 2006;21(1):41-48. http://dx.doi.org/110.1097/00001786-200601000-00010 [ Links ]

15. Bakewell-Sachs S, Gennaro S. Parenting the post-NICU premature infant. Am J Matern Child Nurse 2004;29(6):398-403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200411000-00011 [ Links ]

16. Zelkowitz P, Feeley N, Shrier I, et al. The cues and care trial: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention to reduce maternal anxiety and improve developmental outcomes in very low birth weight infants. BMC Pediatr 2008;26:8-38. http://dx.doi.org/110.1186/1471-2431-8-38 [ Links ]

17. Ortenstrand A, Westrup B, Broström EB, et al. The Stockholm neonatal family-centered care study: Effects on length of stay and infant morbidity. Paediatrics 2010;125(2):278-285. http://dx.doi.org/110.1542/peds.2009-1511 [ Links ]

18. Voos KC, Ross G, Ward MJ, Yohay AL, Osorio SN, Perlman JM. Effects of implementing family-centred rounds (FCRs) in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24(11):1403-1406. http://dx.doi.org/110.3109/14767058.2011.596960 [ Links ]

19. Stevens DC, Helseth CC, Khan MA, Munson DP, Reid EJ. A comparison of parent satisfaction in an open-bay and single-family room neonatal intensive care unit. Health Env Res Design 2011;4(3):110-123. http://dx.doi.org/110.1177/193758671100400309 [ Links ]

20. Abdel-Latif ME, Boswell D, Broom M, Smith J, Davis D. Parental presence on neonatal intensive care unit clinical bedside rounds: Randomized trial and focus group discussion. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2015;100(3):F203-209. http://dx.doi.org/110.1136/archdischild-2014-306724 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

P Batra

drprernabatra@yahoo.com