Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Child Health

versão On-line ISSN 1999-7671

versão impressa ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.10 no.1 Pretoria Jan./Mar. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/saich.2016.v10i1.952

SHORT REPORT

Mothers' reasons for refusing to give consent to HIV testing and the outcome in the children

N ShipalanaI; T S NtuliII

IMB ChB, FCPaed (SA), MMed (Paed); Department of Paediatrics, University of Limpopo (Polokwane Campus), Polokwane, South Africa

IIBSc, BSc Hons, MSc; Research Development and Administration, University of Limpopo (Turfloop Campus); and Department of Public Health Medicine, University of Limpopo (Polokwane Campus), Polokwane, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: HIV/AIDS is one of the most common underlying causes of death in children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years in sub-Saharan Africa. In Limpopo Province, South Africa, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programme introduced in early 2000 and paediatric ARV roll-out have had a poor uptake due to various factors.

OBJECTIVE: To establish the reasons why mothers decline HIV testing for their children.

METHODS: A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at the paediatric ward, Mankweng Hospital, Limpopo, for a period of 1 year (June 2009 - June 2010). All mothers who had declined HIV testing on their children were requested to participate. All the participants gave informed consent.

RESULTS: A total of 30 mothers participated. All women had attended antenatal care, 28 (93%) stated that their HIV results were negative and 2 (8%) had undergone PMTCT. The reasons mothers refused HIV testing on their children included the following: did not want to be stressed with a positive result (67%), did not want to know their status (7%) and could not consent as their partners had declined tests on both baby and mother (7%); 20% had other reasons including fear of HIV stigma. The median age of the children was 13 months (interquartile range 2 months - 10 years). Twenty-one (70%) of children were discharged home after treatment without HIV testing, five (16%) mothers signed refusal of hospital treatment, three (12%) started ARV after the mother reconsidered and signed consent, with good response to highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) and one child died after a month in the hospital.

CONCLUSION: Fear of being stressed by a positive result was the main reason mothers refused an HIV test on their children. Better education about HIV transmission, prevention and the good response to HAART is needed to increase the uptake of HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated global reduction of under-five deaths from 12.6 million in 1990 to 6.6 million (47%) in 2012.[1] Most countries have shown good progress by reducing the under-five mortality rate by more than half since 1990. HIV/AIDS is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in under-five children in sub-Saharan Africa.[2-6] A greater proportion of these children get infected through mother-to-child transmission. Studies have demonstrated that early diagnosis and treatment can reduce morbidity and mortality among these children.[7-11]

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programmes have made it possible to reduce the risk of infection.[12-16] In South Africa (SA), the PMTCT guidelines recommend that diagnostic testing in infants be performed as early as 4 - 6 weeks of age, so that highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) is initiated early, thereby reducing infant deaths.[16] Although PMTCT has been successful, a high proportion of HIV-exposed and HIV-infected infants remain unidentified.[15] In SA, provinces with better health resources have a higher intake of children on HIV/AIDS programmes. Hsiao et al.,[16]in their study conducted in the Western Cape Province of SA, illustrated an increase in the proportion of infected infants successfully linked to HIV care and treatment.[16]

HIV/AIDS is a chronic disease that needs the full understanding and cooperation of a parent and/or guardian to take the child for lifelong treatment. Children with signs of HIV/AIDS need the consent of a parent and/or guardian to perform specific screening or tests for HIV. However, women are still reluctant to give consent for testing on their sick children. The objective of this study is to investigate the reasons why mothers decline HIV testing for their children in a tertiary hospital.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted over a period of 12 months from June 2009 to June 2010 at the paediatric ward of Mankweng Hospital in Limpopo Province, SA. The hospital is a combined district/regional hospital for the local population and a tertiary referral centre, with 46 beds in the paediatric ward. Children under 13 years of age with illness and requiring hospitalisation are admitted to the paediatric ward from the outpatient and emergency departments. The study included all mothers who had declined HIV testing on their children.

During the study period, the practice in the ward was to do HIV testing on all children that had clinical stigma of HIV infection, acute or chronic medical conditions that mimic HIV infection or history of HIV exposure, as well as those whose mothers requested voluntary testing. Where HIV testing was requested by a health worker, the mother was given pretest counselling by an HIV councillor or occasionally by a registered nurse or doctor, especially when she declined the test. The mothers who refused HIV testing on their children were also given pretest counselling.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Limpopo Ethics Committee, Polokwane Campus (Ref: 033/2008). Anonymity and confidentiality of the participants' personal information were protected, and the participants signed informed consent forms before participating in the study. The data for the study were collected by the paediatrician main researcher, and included the mother's age, education, marital and employment status, antenatal care (ANC) visits, voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) results, PMTCT (prevention of mother-to-child transmission), reasons for refusal of an HIV test on their children, baby's age and outcome of the child during the current admission. Categorical data were displayed as percentages. Statistical software (STATA 9.0; Stata Corp, USA) was used for data analysis.

Results

A total of 1 563 children were admitted during the 12-month period of the study. Mothers who were offered testing according to the testing policy of the ward at that time totalled 241. Two hundred and eleven (88%) signed consent for HIV testing of their children and 30 (12%) refused.

Of the 30 mothers who declined HIV testing on their children, 28 (96%) were in the age group 18 - 35 years, 27 (93%) had attempted or passed grade 12, 13 (43%) were single mothers and 18 (60%) were unemployed. All 30 mothers had attended ANC. Most (n=28, 96%) stated that their HIV results were negative, and only two (8%) had undergone PMTCT. Verification of the HIV results was not possible as most ANC HIV tests are rapid tests with no hard copies given to clients and documentation of the results in the child's Road to Health Card (RHC) was not always done. The median age of the children was 13 months (interquartile range (IQR) 2 months - 10 years).

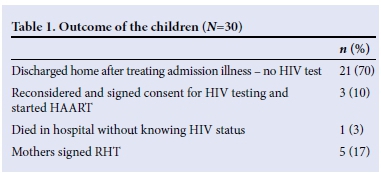

With regard to the children's outcomes, 21 (70%) were discharged home after treatment of the admission illness without confirmation of their HIV status, 3 (10%) started antiretrovirals (ARVs) with good response to HAART after the mother reconsidered and signed consent, and 1 (3%) child died after a month in the hospital. For the remaining 5 (17%) children, their mothers signed refusal of hospital treatment (RHT) and they left the hospital before being well enough to be discharged (Table 1).

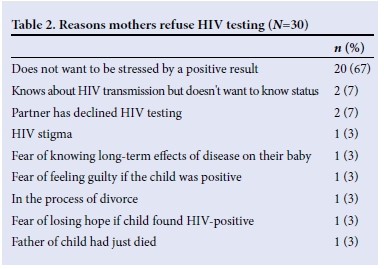

Reasons mothers refused HIV testing on their children included the following: did not want to be stressed with a positive result (67%), did not want to know their status (7%), and could not consent as their partners had declined tests on both baby and mother (7%). The other reasons for refusal are varied due to the open-ended design of the questionnaire (Table 2).

Discussion

This study explored why some mothers refuse HIV testing for their sick children. The SA national strategic plan for HIV and sexually transmitted infections is to expand access to care, treatment and support (80%) of people infected with HIV.[17] Women and children are the most vulnerable groups that need special attention. HIV/AIDS is a leading factor that has contributed to the rising under-5 morbidity and mortality rates and had made it impossible for SA to achieve Millenium Development Goal 4 by 2015.[3,5,18] The roll-out of PMTCT has made it easy for pregnant women to access voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) at their local clinics.[14,16] However, studies have shown that healthcare providers experienced challenges of women unwilling to consent to HIV testing and treatment.[20-22] In our study, all mothers attended ANC, showing that routine ANC is acceptable, and this opportunity can be used to significantly increase HIV testing rates. However, while 96% of women in this study had VCT, their HIV results could not be verified as HIV testing at most ANC sites is done by rapid testing and results are recorded in the mother's antenatal records; no hard copy is given to the client.

Moodley et al.[22]in their study reported that up to 84% of pregnant women had received HIV counselling and testing, and ~90% of them had been tested for HIV. Khan et al.[23] carried out an audit of HIV information on the RHC at rural clinics in Limpopo Province. Their study found that 62% of the pregnant women had had their HIV status documented on their RHC.[231 Despite the high rate of antenatal visits during pregnancy, some barriers for VCT/HIV testing still exist. Studies have shown that the stigmatisation of HIV/AIDS, over-exaggeration of HIV treatment side-effects and women's worry about their partner's reaction if they find out they had tested positive can contribute to unwillingness to have HIV testing and treatment.[21,22] Recently, a study conducted at Mankweng primary healthcare (PHC) facilities in Limpopo revealed that the clients who attended these clinics lacked knowledge regarding VCT, the prevention of HIV infection and support systems available to HIV-positive people.[25]

There are few studies that assessed the reasons why mothers refused HIV testing for their babies. In high-income countries, mothers who refused HIV testing for their children have cited various reasons, including: the perception that a physically well child cannot be infected with HIV, inability to cope with a positive diagnosis in a child, and feeling of guilt if the child tested positive.[26,27] In the present study, the main reason mothers refused HIV testing of their children was that they did not want to be stressed by the positive HIV result of the child.

The involvement of partners in HIV prevention and treatment has been investigated previously in sub-Saharan Africa. A systematic review by the University of Tampere, Finland, showed that men had a positive attitude towards PMTCT programmes even though some barriers existed, such as lack of knowledge or time, stigma of HIV/ AIDS, problem with healthcare services and cultural issues.[29]

The Child Care Act states that the Minister of Social Development can give consent for HIV testing in situations where parents refuse consent or cannot be found.[30] Although healthcare workers have the power to consult and make use of this recommendation, it is not advisable to take this route immediately and do HIV testing where the parent has not given consent, as HIV/AIDS is a chronic disease that needs the cooperation of the parent/guardian to enable continuous treatment of the child. Providing the mother with education and support could help tackle some of the barriers raised in this study.

Study limitations

The major limitation of this study was the small sample size. Another limitation was that while most mothers had had HIV VCT, their HIV status could not be verified as they did not have proof of their test results, which would normally be recorded in their antenatal records or the children's RHCs.

Conclusion

The study explored why mothers refuse HIV testing for their children admitted to a paediatric ward with an acute or chronic illness. Fear of being stressed by a positive result was the most common reason cited for refusal to give consent for HIV testing. The results of our study suggest that better parent/guardian education about HIV transmission and prevention, and the effectiveness of HAART, is needed to increase the uptake of HIV testing.

Acknowledgements. We thank the staff of the paediatric ward for assisting during the data collection, and the mothers of the children admitted in the ward for their cooperation during this study. In addition, thanks to Dr R Muloiwa for providing useful comments and suggestions.

References

1. The United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Report 2013. New York: UNICEF, 2013. http://www.unicef.org (accessed 21 February 2014). [ Links ]

2. Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med 2008;359(21):2233-2244. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0800971] [ Links ]

3. Newell M-L, Coovadia H, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: A pooled analysis. Lancet 2004;364(9441):1236-1243. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17140-7] [ Links ]

4. De Martino M, Tovo PA, Balducci M, et al. Reduction in mortality with availability of antiretroviral therapy for children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. JAMA 2000;248(2):2871-2872. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.2.190] [ Links ]

5. Van Deventer JD, Carter CL, Schoeman CJ, Joubert G. The impact of HIV on the profile of paediatric admissions and deaths at Pelonomi Hospital, Bloemfontein, South Africa. J Trop Paediatr 2005;51(6):391-392. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmi038] [ Links ]

6. Ntuli ST, Malangu N, Alberts M. Causes of deaths in children under-five years old at a tertiary hospital in Limpopo Province of South Africa. Glob J Health Sci 2013;5(3):95-100. [http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p95] [ Links ]

7. Penazzato M, Prendergast A, Tierney J, Cotton M, Gibb D. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children under 2 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;7:CD004772. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004772.pub3] [ Links ]

8. Boyle DS, Lehman DA, Lillis L, et al. Rapid detection of HIV-1 proviral DNA for early infant diagnosis using recombinant polymerase amplification. MBio 2013;4(2):pii: e00135-13. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00135-13] [ Links ]

9. Wamalwa DC, Farquhar C, Obimbo EM, et al. Early response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;45(3):311-317. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318042d613] [ Links ]

10. Kilewo C, Karlsson K, Ngarina M, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding by treating mothers with triple antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: The Mitra Plus study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52(3):406-416. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b323ff] [ Links ]

11. Thior I, Lockman S, Smearton LM, et al. Breastfeeding plus infant zidovudine prophylaxis for 6 months v. formula feeding plus zidovudine for 1 month to reduce mother-to-child transmission in Botswana: A randomized trial: The Mashi study. JAMA 2006;296(7):794-805. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.7.794] [ Links ]

12. Wortley PM, Lindegren ML, Fleming PL. Successful implementation of perinatal HIV prevention guidelines. A multistate surveillance evaluation. MMWR Recommendation Rep 2001;50(RR-6):17-28. [ Links ]

13. Siegfried N, van der Merwe L, Brocklehurst P, Sint TT. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7):CD003510. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003510.pub3] [ Links ]

14. National Department of Health, South Africa. Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Children. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health, 2010. http://familymedicine.ukzn.ac.za/Libraries/Guidelines_Protocols/2010_Paediatric_Guidelines.sflb.ashx (accessed 17 February 2014). [ Links ]

15. Lillian RR, Kalk E, Technau KG, Sherman GG. Birth diagnosis of HIV infection in infants to reduce infant mortality and monitor for elimination of mother-to-child transmission. Paediatric Infect Dis J 2013;32(10):1080-1085. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e318290622e] [ Links ]

16. Hsiao NY, Stinson K, Myer L. Linkage of HIV-infected infants from diagnosis to antiretroviral therapy services across the Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS One; 8(2):e55308. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055308.Pub_2013_Feb_6] [ Links ]

17. National Department of Health, South Africa. National Strategy Plan on HIV, STIs and TB 2012-2016. 2011. http://www.hst.org.za (accessed 17 February 2014). [ Links ]

18. Draper B, Abdullah F. A review of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme of the Western Cape provincial government, 2003-2004. S Afr Med J 2008;98(6):431-434. [ Links ]

19. Kumbi S, Bedri A, Abashawl A, Isehak A, Coberly JS, Ruff AJ. Reasons for refusal of HIV testing in two Ethiopian antenatal clinics. Abstract (No. 4970:4970), International AIDS Society, Poster Exhibition: The XIV International AIDS Conference. [ Links ]

20. Rosa H, Goldani MZ, Scanlon T, et al. Barriers for HIV testing during pregnancy in Southern Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública 2006;40(2):220-225. [ Links ]

21. Pool R, Nyanzi S, Whitworth JA. Attitude of pregnant women towards VCT in rural south-west Uganda. AIDS Care 2001;13(5):605-615. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120120063232] [ Links ]

22. Moodley D, Srikewal J, Msweli L, Maharaj NR. A bird's eye view of PMTCT coverage at two regional hospitals and their referral clinics in a resource-limited setting. S Afr Med J 2011;101(2):122-125. [ Links ]

23. Khan RBI, Robertson BA, Railton J, Gani S, Tsolo F. An audit of the HIV information documented on the road-to-health cards of children attending primary health care clinics in Capricorn district of Limpopo Province. S Afr Paediatr Rev 2012;9(1):4-8. [ Links ]

24. Ramoraswi MM, Lekhuleni ME, Mbambo-Kekane NP, Mpolokeng M. Knowledge of clients regarding voluntary counselling and testing at Mankweng primary health care facilities at Capricorn District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recreation Dance 2013;19(4):62-74. [ Links ]

25. Eisenhut M, Kawsar M, Connan M, Balachandran T. Why are HIV-positive mothers refusing to have their children screened for vertically transmitted HIV infection? Int J STD AIDS 2009;20(7):506-507. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2008008508] [ Links ]

26. Andrews S, Handyside R, Carpenter L, Price A, Majewska W, Prime K. Testing children of mothers with HIV infection: Experience in three south-west London HIV clinics. HIV Med 2012;13(2):138-140. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00948.x] [ Links ]

27. Hussain R, McMaster P. An audit on HIV testing of children born to HIV positive mothers. Arch Dis Child 2011;95(7):569. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/abc.2009.175778] [ Links ]

28. Auvinen J, Kylmä J, Suominen T. Male involvement and prevention of mother- to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: An integrative review. Curr HIV Res 2013;11(2):169-177. [ Links ]

29. The South African Medical Association. Human Rights and the Ethical Guidelines on HIV and AIDS 2006: A Manual for Medical Practitioners. https://www.samedical.org (accessed 21 February 2014). [ Links ]

30. McQuoid-Mason D. Routine testing for HIV ethical and legal implications. S Afr Med J 2007:97(6):416. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

N Shipalana

shipalanan@vodamail.co.za