Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Child Health

On-line version ISSN 1999-7671

Print version ISSN 1994-3032

S. Afr. j. child health vol.9 n.3 Pretoria Aug. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJCH.7944

ARTICLE

Viability in delivering oral health promotion activities within the Health Promoting Schools Initiative in KwaZulu-Natal

M ReddyI; S SinghII

IMDent PH; Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIPhD; Discipline of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: The Health Promoting Schools Initiative can provide a platform to explore integration of oral health promotion activities within the broader context of healthcare delivery.

OBJECTIVES: To understand the contextualised delivery of oral health service provision within Health Promoting Schools, to conduct a situational analysis of existing services provided at these schools and to review current health and education policies.

METHODS: The explorative study design used a mixed methods approach. Twenty-three schools of a total sample of 154 were selected using multistage cluster sampling. Data collection comprised policy reviews, a self-administered questionnaire, a data capture sheet and an interview schedule. The study was approved by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (HSS/0509/013D.

RESULTS: Although policies included statements on oral health promotion, this was not translated into practice at school level. Barriers and challenges identified for successful implementation of an oral health promotion programme included lack of funds, human resources, knowledge and ownership, as well as high workloads and time constraints.

CONCLUSION: Current delivery of oral health promotion services within the Health Promoting Schools Initiative will not reap the desired oral health outcomes owing to the inherent mismatch between policy planning and implementation. More research needs to be conducted to address opportunities and challenges facing educators and other oral healthcare providers working in the school environment.

The Health Promoting Schools Initiative is recognised as a viable platform to provide integrated and comprehensive oral healthcare.[1] This approach differs from traditional school-based settings in that greater accountability is placed on supportive environments, development of school-based policies, community participation, and focus on disease prevention and promotion of healthier lifestyles.[1] The initiative can provide a platform to explore integration of oral health promotion activities within the broader context of healthcare delivery. Oral healthcare should be seen as an essential part of general health. Interventions could include promotion of a healthy diet, oral health education, tobacco cessation, safe water and sanitation, water fluoridation, tooth brushing and fluoride rinsing programmes.[2]

Schools in South Africa (SA) are graded according to quintiles, which range from quintile 1 (the poorest) to quintile 5 (least poor). Presently, school health services give greater priority to quintile 1 and 2 schools.[3] The literature suggests an inequitable distribution of school health services in KwaZulu-Natal.[3] This could be due to multiple factors that include shortage of personnel, transport and equipment.[3,4] These challenges are more prevalent in rural communities and, given the burden of oral diseases and huge unmet oral health need, these problems are further compounded by access and availability of health services.[5] School oral health promotion programmes currently in place are inconsistent, inequitably distributed and lack monitoring and evaluation.[5]

There are over 1 000 Health Promoting Schools that have been established in SA since 1999.[6-8] However very little research has been done to assess the progress of this initiative, specifically in relation to oral health promotion in KwaZulu-Natal.

International experience indicates the importance of conducting a needs analysis prior to the implementation of health programmes. Understanding of the system's capacity (in this case the school) to support programme implementation - in terms of resources, budgetary allocations, inclusive decision-making and monitoring and evaluation - will contribute to the programme's sustainability.

A needs analysis could include sociodemographic profile, socio-economic status, health and oral health status, availability of dental and school health services, nutritional status, infrastructure, available resources, funding and evidence of community participation.

This presentation is part of a bigger project that examines the viability of integrating oral health promotion activities within the Health Promoting Schools Initiative. This article reports only on the current capacity of Health Promoting Schools to support oral health promotion in KwaZulu-Natal.

Objectives

To understand the contextualised delivery of oral health service provision within Health Promoting Schools, to conduct a situational analysis of existing services provided at these schools, and to review current health and education policies.

Methods

The explorative study design used a mixed methods approach, with a combination of qualitative and quantitative data. Data source triangulation was used to combine evidence from multiple data sources. A structured self-administered questionnaire, data capture sheet and interview schedule were used to collect data. Policies were also reviewed for identification of current policy priorities in health and oral health promotion.

There are 154 primary Health Promoting Schools in KwaZulu-Natal. Twenty-three schools were selected from the 11 districts using multistage cluster sampling. Schools were selected according to districts and then quintiles. The study sample (n=23) comprised two or three schools from each district and four or five from each quintile.

The sample population for the interview phase comprised the Basic Education manager involved with health promotion, and the provincial and district (eThekweni, Ugu, iLembe and Uthukela) health promotion managers from the Department of Health. These participants were selected using purposeful random sampling.

The self-administered questionnaire, which focused on oral health promotion, school health services, community relationships and collaboration, and barriers and challenges experienced, was completed by school principals. Fieldworkers involved in data collection observed and recorded the school's physical and environmental condition on a data capturing sheet. The interview schedule included questions on the importance and awareness of oral health promotion at schools, and opportunities and challenges facing integration of oral health promotion services.

A pilot study was conducted to pretest the questionnaire at two schools not included in the study, prior to commencement of data collection.

Validity was maintained by ensuring that the questionnaire and interview focused on the study's objectives. Reliability was ensured by standardising the use of codes and identified themes.

Gatekeeper permission was obtained from Department of Health and Department of Education. The study was approved by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (HSS/0509/013D). The University of KwaZulu-Natal ethical guidelines were used to ensure confidentiality, consent to conduct interviews and proper data management.

Results

The results of the study are a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, and are presented to address the objectives of the study.

Policy document review

Table 1 presents the list of policies and documents that were reviewed.

The Youth and Adolescent Policy[12] and Integrated School Health Policy[4] identified the need to improve and strengthen existing school health services. However, there was no direct mention of oral health promotion in these policy statements.

The SA National Oral Health Strategy (2004)[9] and Draft National Oral Health Strategy (2010)[10] prioritised the improvement of oral health for all citizens through oral health promotion. School screenings for oral health were mentioned in the School Health Policy and Implementation Guidelines[3] and Integrated School Health Policy.[4]

However, reports from interviews with managers indicated a lack of priority given to oral health, as reflected in the following quotation: 'There is awareness to [sic] basic hygiene being included in the curriculum but not oral health' (interview with Manager A).

Managers did, however, identify the need to give priority to oral health promotion: 'Oral health promotion was identified as a critical gap in the Health Promoting Schools Initiative and it is vital that it be part of the health promotion programme so that it would enable children to take care of their teeth and prevent long-term oral health problems' (interview with Manager C). Responses to the questionnaire for school principals indicated that five schools (21.8%) had comprehensive oral health policies in place but only one school provided supporting evidence.

Situational analysis

The majority (60.9%) of schools in the study sample (n=23) were located in rural areas, 26.1% (n=6) in peri-urban areas and only 13% (n=3) were located in urban areas. An assessment of the condition and environment of the schools is outlined in Table 2.

All respondents (n=14) (Table 2) in the rural areas and 89% of respondents in the urban and peri-urban areas reported that health messages formed part of the curriculum. Water supply and safety in the urban and peri-urban areas was reported as good (100%) compared with rural water supply and safety (64.3%). Most respondents in the rural areas (78.6%) and 44.4% in the urban and peri-urban areas reported that recycling was inadequate. Playground conditions in the rural areas were reported as inadequate (57%) compared with 33.3% inadequate in the urban/peri-urban areas. Only 50% of the respondents in the rural areas reported that sanitation and the condition or number of the toilets was fine. Seven respondents (77.8%) in the urban/peri-urban areas were satisfied with sanitation and availability of toilets.

All respondents indicated that 71.4% ofthe schools had clinics in close proximity to the schools, while 57.1% indicated that hospitals and police stations were located within a 30 km radius. Recreational facilities such as sporting activities were not easily accessible to 71.4% of the schools. Respondents from the rural areas also reported that road conditions were poor and transport and resources limited.

Eighty-seven per cent of respondents reported that School Health Services and screenings were provided annually by the Department of Health. Supporting evidence was provided in the school visitors log book.

Responses from interviews with provincial and district health managers (100%) indicated that school health nurses lacked expertise and knowledge in oral health promotion, had large areas to support, and had high workloads and limited staff and resources. Respondents also stated that there should be an increase in human resources, especially oral hygienists. The Department of Health Strategic Plan 2010 - 2014[13] further validates this view by suggesting an increase in the employment of dental health practitioners.

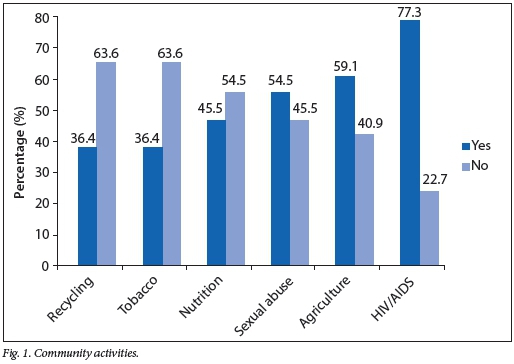

Forty-eight per cent of the study sample indicated that community involvement in school health programmes was voluntary, and that some parents expected payment for their assistance. The activities that communities were involved in are illustrated in Fig. 1. These activities include HIV/AIDS (77.3%), sexual abuse (54.5%) and agriculture (59.1%), compared with recycling (36.4%), tobacco use (36.4%) and nutrition and food safety (45.5%).

Eighty per cent of rural schools indicated community awareness in nutrition, basic hygiene, cleanliness and gardening. A small percentage (13.6%) of schools indicated an improvement in nutrition as indicated by the following response: 'Pupils eat healthy foods from the nutrition programme and the community is aware that the school promotes healthy food' (response to questionnaire).

Priorities for health promotion and oral health promotion

Of the total sample (n=23) of schools, 72.7% of respondents indicated oral health services in place. Oral health services offered at the schools is illustrated in Fig. 2. Oral health education (81.8%, p=0.003) was the most common activity conducted at schools, and fissure sealant placement (9.1%, p=0.000) the least. However, supporting evidence in school record books indicated that there was inconsistency in these activities, as they occurred only once at one of the schools and once a year in 65% of the schools.

The sale of healthy foods was mentioned by three respondents (13%). The majority of the respondents (87%) indicated major barriers in the sale of healthy foods to children, e.g. 'Tuck shop outsourced - limited control' and 'No healthy foods are sold at the tuck shop' (responses to questionnaire).

Health promotion training for school staff was not present in the majority (61.9%) of the schools. This was also highlighted as a problem by the district managers. Staff indicated that they lacked basic knowledge in oral health, which resulted in a lack of confidence in the implementation of oral health promotion programmes. Challenges experienced by staff for the implementation of an oral health promotion programme included lack of resources (22%), funds (26%), time constraints (22%), large classes (4%) and support from parents and community (30%).

Discussion

The policy process is recognised as an integral component to guide implementation and sustainability of a programme.[5,14] One of the key policy priorities identified was a need for an integrated approach to health that looked at common risk factors; however, this was not evident as very little priority was given to oral health. Poor oral health and chronic diseases such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases and trauma share common contributory factors such as poor hygiene and diet, smoking and alcohol abuse. The common risk factor approach, which is a more collaborative approach, should therefore be adopted to avoid duplication and to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of health programmes.[15]

The study findings indicated that school principals expressed lack of knowledge and understanding on related health and education policies, compounded by a lack of support from the Department of Education. Oral health screening is included in The Integrated School Health Policy,[4] but there was no evidence of oral health education as a formal component in the school curriculum. Oral health promotion was also perceived as an additional burden on the teaching workload and was not part of the daily routine programme owing to time constraints, high workloads, lack of knowledge and confidence. It is imperative that oral health education be formally included into the school curriculum. Although the study findings indicated an array of oral health promotion activities at the schools (Fig. 2), caution must be exercised in the interpretation of these results as these activities were conducted either once or occurred only once a year. These findings therefore highlight the need for greater collaboration and dialogue between the Departments of Health and Education. Shared resources for oral health screenings and oral health promotion programmes would relieve the burden on resources and could contribute to greater programme sustainability. Commitment from the national, provincial and regional Departments of Health and Education and schools is critical. This commitment requires strategic planning and resource allocation that could support and ultimately sustain the delivery of the integrated school health programmes.

Designated educators at school should work in close collaboration with health and oral health personnel with greater accountability and 'ownership' in these programmes. Further research needs to be conducted to assess the challenges facing educators with these additional responsibilities.

The policy review revealed that the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education Draft National School Nutrition Programme Policy[16] had guidelines for school vendors and tuckshops. However, findings in this study suggest that this has not been translated into practice. Major barriers were encountered by schools in the sale of healthy foods to children by vendors and tuckshop owners. Although vendors and tuckshop owners were educated and encouraged to buy into the notion of healthy eating, this was not always practical. Healthy foods were seen as too expensive. Schools need to negotiate formal contracts with tuckshop owners and vendors to ensure alignment with the policy. More research is required to further address the challenges related to the implementation of healthy nutritional policies in schools.

Financial restraints and a high turnover (27.7%) and vacancy rate (37.3%) for dental health practitioners were also identified in the Department of Health Strategic Plan 2010 - 2014.[13] The vacancy rate for oral hygienists was 51.9%, negatively affecting oral health education and school screening services.[13] It was also noted that the sustainability of programmes at schools was a challenge due mainly to poor buy-in from the Department of Education.[13] Oral health personnel were mostly hospital based and provided more curative rather than preventive services.[5,17] District managers also reported that preventive programmes did not receive recognition for prioritisation for budgetary allocations. Oral health promotion requires a dedicated budget.

The strategy for the Oral Health 10 Point Plan (2011 - 2015)[11] in KwaZulu-Natal includes the establishment of comprehensive preventive and promotive oral health programmes; however, current shortage of oral health personnel affects the delivery and sustainability of these programmes.[18] The draft National Oral Health Strategy (2010) indicates that oral health promotion and services should be included in health promotion at schools and that nurses, teachers and community health workers should be utilised for oral health promotion programmes.[10] In view of the challenges being faced by educators and school health services, a needs analysis and epidemiological profile should be performed so that resource allocation is based on unmet oral health needs and is in response to the needs of the community. There should also be ongoing stakeholder involvement from the planning to the execution and evaluation of oral health interventions. Additional funding needs to be allocated and more nurses and oral health personnel employed for the success of these strategies and interventions.

Policy formulation and strategic planning must include educators and healthcare workers at grassroots level for the successful implementation and sustainability of oral health promotion programmes. More research needs to be done to support the translation of policy into practice. The focus should be on the process of how these interventions are executed and monitored.

Community support services such as hospitals and clinics are integral for follow-up to school health visits. Although the availability of community support services in rural areas was identified in this study, these are not easily accessible owing to poor roads and transport, and limited resources.[10,13]

The study findings revealed that the conditions and environment of schools were generally good and compliant with the requirements of a Health Promoting School; however, attention still needed to be given to recycling, condition of playgrounds and sanitation in rural areas.

Community awareness and participation was poorly defined and inconsistent. The results further indicated that communities were not aware of available preventive services and follow-up practice for oral health. Schools need to create awareness and improve links with communities through in-depth community engagement programmes in order to facilitate community participation and ownership in decision-making processes. This would be in keeping with requirements of a Health Promoting School.[1]

The availability of clean water and other resources could create challenges in terms of uninterrupted delivery of oral health promotion activities. Furthermore, resources required to ensure healthy lifestyle practices are not available to most families in rural and semirural communities.[6,19,20]

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that current delivery of oral health promotion services within the Health Promoting Schools Initiative will not reap the desired oral health outcomes due to the inherent mismatch between policy planning and implementation. More research needs to be conducted to address the opportunities and challenges facing educators and other oral healthcare providers working in the school environment.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Information Series on School Health. Oral Health Promotion: An Essential Element of a Health-Promoting School. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [ Links ]

2. Kwan SYL, Petersen PE, Pine CM, Borutta A. Health-promoting schools: An opportunity for oral health promotion. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83(9):677-85. [ Links ]

3. Department of Health, South Africa. School Health Policy and Implementation Guidelines, 2011. www.rmchsa.org/.../SchoolHealth/SchoolHealthPolicy&Guidelines.docx (accessed 30 April 2014). [ Links ]

4. Department of Health and Basic Education, South Africa. Integrated School Health Policy, 2012:1-39. www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=pjcIv8qGMc%3D&tabid=390&mid=1125 (accessed 4 March 2013). [ Links ]

5. Singh S. Dental caries rates in South Africa: Implications for oral health planning. S Afr J Epidemiol Infect 2011;26(4 Part II):259-261. [ Links ]

6. Johnson B, Lazarus S. Building health promoting and inclusive schools in South Africa. J Prev Interv Community 2003;25(1):81-97. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J005v25n01_06] [ Links ]

7. Department of Health, South Africa. National Guidelines for the Development of Health Promoting Schools/Sites in South Africa (Draft 4). Pretoria: Department of Health, 2000. [ Links ]

8. Shasha Y, Taylor M, Dlamini S, Aldous-Mycock C. A situational analysis for the implementation of the National School Health Policy in KwaZulu-Natal. Dev South Afr 2011;28(2):293-303. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2011.570077] [ Links ]

9. Department of Health, South Africa. National Oral Health Strategy. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2004. http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/index.html (accessed 30 April 2014). [ Links ]

10. Department of Health, South Africa. National Oral Health Strategy (confidential draft for comment only). 2010:1-15. [ Links ]

11. Department of Health, KwaZulu-Natal. Annual Report - Vote 7, 2011/2012:43. www.kznhealth.gov.za/1112report/partA.pdf (accessed 22 August 2013) [ Links ]

12. Department of Health, South Africa. Policy Guidelines for Youth and Adolescent Health. Pretoria: Department of Health, 2001:1-72. [ Links ]

13. Department of Health, South Africa. KwaZulu-Natal - Strategic Plan 2010 - 2014. 2010:68-69. www.kznhealth.gov.za/stratplan2010-14pdf (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

14. Singh S. A critical analysis of the provision for oral health promotion in South African Health Policy Development. PhD thesis. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape, 2005. http://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/11394/1960 (accessed 14 July 2012). [ Links ]

15. Sheiham A, Watt RG. The Common Risk Factor Approach: A rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2000;28(6):399-406. [ Links ]

16. Department of Education KwaZulu-Natal. National School Nutrition Programme Policy (Draft). Pretoria: Department of Education, 2011. www.kzneducation.gov.za/Portal/O/Circuiars/General/2012/NSNP%20Draft%20Policy20111122(1)pdf (accessed 1 November 2012). [ Links ]

17. Singh S, Myburgh NG, Lalloo R. Policy analysis of oral health promotion in South Africa. Glob Health Promot 2010;17(16):16-24. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1757975909356631] [ Links ]

18. James S, Moodley V. The health of older children in a school setting. In: Health Systems Trust. South African Health Review. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2006:283-296. [ Links ]

19. Edwards-Miller J, Taylor M. Making a difference to school children's health. In: Health Systems Trust. An Evaluation of School Health Services in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 1998. www.hst.org.za/publications/making-difference-school-childrens-health (accessed 1 November 2012). [ Links ]

20. Swart D, Reddy P. Establishing networks for Health Promoting Schools in South Africa. J Sch Health 1999;69(2):47-50. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M Reddy

reddym@ukzn.ac.za

This work is part of a larger study conducted in fulfilment of the first author's PhD degree in Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal.