Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Bioethics and Law

On-line version ISSN 1999-7639

SAJBL vol.16 n.2 Cape Town Aug. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/sajbl.2023.v16i2.694

ARTICLE

Catch-22: A patient's right to informational determination and the rendering of accounts by medical schemes

M BotesI; A E ObasaII

IBProc, LLB, LLM, LLD; Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

IIBSc, MSc, PhD, PGDip (Applied Ethics); Registrar Research Support Office, Research and Internationalisation, Development and Support Division, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Many people who have reached the age of majority still qualify as financial dependents of their parents, and may be registered as dependents on their parents' medical schemes. This poses a practical conundrum, because major persons enjoy complete autonomy over their bodies to choose healthcare services as they please, including informational determination. However, their sensitive health information may end up being disclosed in the accounts rendered to their parents, as main members of medical schemes, thereby breaching their informational privacy, medical confidentiality and possibly also damaging personal relationships. On the other hand, medical schemes must ensure that they strictly manage the business of their hospitalisation to ensure that they can adhere to their contractual and legal medical insurance obligations. Both major but financially dependent patients and medical schemes have good legal grounds to defend their respective positions. In this article, we will analyse and clarify the applicable legal and ethical grounds by considering medical confidentiality, the Protection of Personal Information Act, the Consumer Protection Act and the Medical Schemes Act and rules. We shall conclude with recommendations to accommodate the interests of both parties.

Parents of major children who are still financially dependent on them are entitled to keep them registered as dependents on their medical scheme, if their dependence meets the eligibility criteria as per the rules of the medical scheme. The Medical Schemes Act No. 131 of 1998 (MSA)[1] determines that a dependent child qualifies either as a child dependent, if the child is aged <21 years, or an adult dependent, if the child is >21, for purposes of enjoying medical scheme coverage, and the parent (main member of the medical scheme) is 'liable for that child's care and support'.[1] Accordingly, some major persons enjoy healthcare paid for by a medical scheme, or partially paid for by their parent as main member of the medical scheme.

Although many of the forms that patients must complete before consulting a private medical practitioner ask the patient to indicate to whom the account for any co-payments must be sent, it is unlikely that financially dependent major children will indicate themselves in these circumstances. Subsequently, the main member usually receives all medical accounts in this context. On face value, this scenario may seem beneficial to all parties involved. However, a major 'child' still enjoys full independent autonomy over their body and choices of medical treatments, regardless of their financial dependency status and medical scheme membership. This situation may lead to medical treatment choices or health status information of a very personal and sensitive nature (which the patient may choose to keep private and confidential) being disclosed to the main member of the scheme via medial accounts. In this article, we analyse the patient's right to medical confidentiality and informational self-determination, and how the rules for medical schemes require the implementation of privacy-preserving technologies to safeguard the privacy of patients' information. For purposes of practical illustration, we based our discussions on a fictional, but realistic, case study.

Case study

Mr W is a 20-year-old homosexual male who visited a private clinic where he was diagnosed to be living with HIV. He is a beneficiary of his parent's medical aid; therefore, the medical account is sent to his father as the main member of the medical scheme. Mr W's parents are neither aware of his sexual orientation, nor of his HIV status. His parents hold religious reservations about homosexuality, with his father serving as a senior pastor in a faith-based organisation. Mr W does not want to disclose his HIV status or sexual orientation to his parents.

Navigating a medical scheme account

Medical schemes provide private health insurance to individuals and families to access private healthcare services. In South Africa (SA), medical schemes are typically funded by contributions from members, and offer a range of benefits that can include coverage for hospitalisation, medical consultations, diagnostic tests, medication and other healthcare services. The level of coverage provided by a medical scheme is dependent on the elected plan and contributions made by the main member.

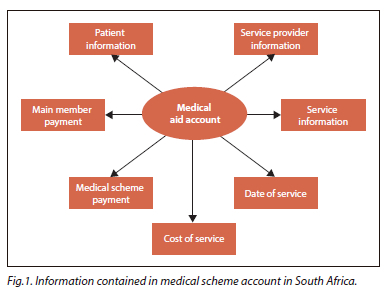

An account rendered by a medical scheme to its main members provides a detailed breakdown of the costs incurred for medical services, including the amount paid by the medical scheme and the co-payments owed by the main member, and typically includes the information in Fig. 1:

• Patient information: this includes the patient's name, medical aid membership number and sometimes their address and contact details.

• Provider information: this includes the name and contact details of the healthcare provider or facility that provided the service or treatment.

• Service information: this includes a description of the medical service or treatment provided, including any diagnostic codes, procedure codes, or medication codes used.

• Date of service: this is the date on which the service or treatment was provided.

• Cost of service: this is the amount charged for the service or treatment provided, and may include both the amount charged by the healthcare provider as well as any co-payments or deductibles that the patient may be responsible for paying.

• Medical scheme payment: this is the amount that the medical aid scheme paid towards the cost of the service or treatment.

• Main member payment: this is the amount that the main member is responsible for paying, which may include any co-payments or deductibles.

International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) and considered to be the global standard for diagnostic health information, are used worldwide to record information about health and statistics on disease to support payment systems and service planning.[2] These codes are also used by healthcare services and medical schemes in SA to process payment requests, and appear on accounts rendered to main members of medical schemes. On the one hand, it can sometimes be challenging for patients to understand what the ICD codes or descriptions on their medical accounts mean, as these codes can be highly technical and difficult to interpret without specialised medical knowledge. But, on the other hand, clinical support services receive numerous queries from both medical practitioners for clarity on which code to use for a specific treatment, and from members of the public about incorrect usage of ICD codes, especially when medical schemes refuse to pay for health services indicated by a specific ICD code.[3] In some cases, medical schemes or healthcare providers may even provide patients with additional information about the ICD codes or descriptions on their medical accounts to help them better understand their medical conditions and the treatments they received. In SA, as of 2015, almost 95% of all South Africans could read and write, which theoretically means that these persons, especially those who can afford medical insurance, have 'average literacy skills' and should be able to look up the meaning of specific ICD codes on the internet, or the specific medical practitioner to determine his/ her field of expertise and the type of health services (s)he offers.[4]

Mr W's father thus has sufficient and easily accessible resources in the form of reputable online medical platforms available to help him to ultimately determine Mr W's health status. Below, we argue why these codes are not adequate to protect the privacy of sensitive special personal information such as Mr W's HIV status.

A network of legal-ethical issues Confidentiality

When Mr W consulted a doctor, he entered into a contractual relationship, not only with regard to the terms and conditions of potential medical services, but also to the effect that any information that he divulges to the doctor, whether through words or other means such as his HIV test results, must be kept private and confidential by that doctor - unless and until Mr W consents to its release.[5] The right to privacy and confidentiality founded in the doctor-patient relationship, specifically with regard to a patient's HIV status, has also been confirmed in Jansen van Vuuren v Kruger, where the judges concurred that a patient has the right to 'expect due compliance by the practitioner with his professional ethical standards'.[6] The confidence and trust imparted by this confidentiality and privacy allow for honest disclosure of health and lifestyle choices that enable appropriate and effective medical treatment.

Subject to certain exceptions such as the reporting of notifiable medical conditions,[7] or contractual obligations to safeguard legitimate business interests,[8] doctors are prohibited from disclosing patient information to any other person not involved in the treatment of that patient. But, because of the infectious and serious nature of HIV/AIDS, the SA Medical Association (SAMA) guidelines require the doctor to 'counsel the patient on the need to inform third parties at risk, such as sexual partners, and even to 'attempt to obtain the patient's informed consent and offer to assist in the process of disclosure'.[9] Not even a patient's family has the right to know his or her HIV status, considering the impact that this disease may have on his/her relationships with parents, partners or children.[10] In addition, the SAMA guidelines are very clear that although principal members of medical schemes are paying for the medical services provided, the principal member has 'no automatic right to obtain the medical information of his/her dependants', and that any standardised codes that are being used by the particular medical scheme in accordance with their rules and regulations must still preserve patient confidentiality.[10] Even when discussing a patient's HIV status during hospital ward rounds, 'no referral under any circumstances' can be made to that patient's HIV status in the vicinity of student doctors who may be unaware of the patient's health status: instead, 'another word/code' must be used to refer to such status, but still 'care must be taken to ensure that the meaning of such a code doesn't become common knowledge'.[11] However, care must be taken to not use any standardised coding system that ultimately risks becoming a replacement name for the specific disease or health status, completely defying the privacy goal. Skinner and Mfecane[12] found that ongoing stereotyping and stigma attached to HIV/AIDS, which was directly coupled with the persistence of discrimination based on factors such as race, gender and sexual orientation, still greatly impacted the confidentiality debates relating to HIV and the disclosure of information relating to it.

For this reason, the obligation to keep all information relating to a patient's health status, treatment, or stay in a health establishment confidential has been codified in the National Health Act No. 61 of 2003,[13] which states that information may only be disclosed to third parties not involved in the treatment of the patient on the basis of the patient's written consent, a court order, or if non-disclosure represents a serious threat to public health. The types of health information thus protected include diagnostic, health status and treatment information, and the fact that a patient has visited or stayed in a particular health facility. This means that the doctor must first obtain Mr W's written consent before (s)he is allowed to answer any enquiries by Mr W's father about whether his son has visited a HIV clinic or is a patient of a particular specialist or practitioner. The general rule proposed by SAMA is that doctors must request a certified copy of the patient's written consent to information disclosure, or for an exact reference to the specific section in a law that authorises the third party to access such information.[10] However, any request for access to health information in general in the absence of the patient's written consent may be refused if it amounts to unreasonable disclosure, which includes requests by family members for a person's HIV status or health information, or requests by lawyers or insurers.[7,10,14]

Informational self-determination and privacy

Patients themselves are the ultimate decision-makers with regard to their own bodies, health and medical information.[15] This right to self-determination is contained in section 12(2) of the SA Constitution,[16] which stipulates that everyone has the right to freedom and security of their person, which entails the right to bodily and psychological integrity and the right to security in and control over their body. The right to self-determination finds further expansion through the constitutional right to privacy and the right to control one's personal information as per the conditions provided for in the Protection of Personal Information Act No. 4 of 2013 (POPIA).[17] But when self-determination becomes mingled with 'consumer rights' this results in medical scheme business models that are challenging the laws and practices of informational privacy and information disclosure. Even though doctors are trying to safeguard confidential personal information in accordance with the wishes of their patients, their professional ethics and privacy laws, practical mechanisms of rendering accounts to principal members of medical schemes are risking the disclosure of patients' sensitive personal information, such as Mr W's HIV status to his father. In this context, information privacy has also been described as the 'ability of individuals to determine the nature and extent of information about them which is being communicated to others', which emphasises the aspect of unauthorised access or use of information.[18]

Consent, which has historically been used for self-determination with regard to decision-making involving one's body and health, has now also been used in POPIA as a tool to control personal information flows, also referred to as informational self-determination. In terms of POPIA, any information about a person's health or sex life is categorised as 'special personal information' that carries a general prohibition against being processed by anyone, unless processing is carried out with the consent of the data subject.[19] However, this prohibition, specifically with regard to a person's health or sex life, does not apply when 'insurance companies, medical schemes, medical scheme administrators and managed healthcare organisations' are processing such information 'for the performance of an insurance or medical scheme agreement' or 'the enforcement of any contractual rights and obligations'.[19]

In essence, an insurance contract, including one for medical insurance, is a legal agreement between an insurer (the medical scheme) and an insured (the principal member or patient) that transfers the risk or responsibility for payment of medical expenses incurred by the principal member or his/her dependants to the medical scheme in accordance with the terms and conditions stipulated in the contract, in exchange for a fixed monthly payment called a premium. This contract stipulates in detail the conditions of coverage and the responsibilities of both parties.

Accordingly, medical schemes may process information about Mr W's health status and/or sex life in terms of POPIA by 'retrieving', 'organising', 'disseminating by means of transmission' and 'distributing or making available in any other form', such as an account rendered to his father, the principal member of the medical scheme and party responsible for any co-payments in terms of the insurance contract, without the consent of Mr W. This is legally allowed, because such processing is considered to be necessary for the performance of their insurance or medical scheme agreement, or the enforcement of their contractual rights and obligations - or is it?

Section 29(d) of the Medical Schemes Act No. 131 of 1998 (MSA)[20] stipulates that a medical scheme shall only be registered and carry on business when that scheme's rules provide (among other matters) for the 'manner in which contracts and other documents binding the medical scheme shall be executed'.[20] Without detracting from the nature or content of insurance contracts, this provision provides medical schemes with freedom regarding the manner in which they wish to execute their contractual rights and obligations as per their internal rules. In this regard, the explosion in privacy-preserving technologies spoils medical schemes for choice when it comes to implementing a suitable technology to preserve the informational privacy of Mr W, which will subsequently impact the manner in which a contract may be executed, without interfering with the content of the contract. The exact nature and functionalities of such technologies unfortunately fall outside the scope of this article.

Considering the information that must be reflected in accounts rendered to the 'member or to a dependent of such a member', section 59 of the MSA stipulates that accounts must, notwithstanding the provisions of any other law, contain 'such particulars as maybe prescribed'.[20] These particulars are described as follows in the medical scheme rules of (for example) the Government Employees Medical Scheme (GEMS):[21]

'15.1.1. the surname and initials of the member;

15.1.2. the surname, first name, and other initials, if any, of the patient;

15.1.3. the name of the scheme;

15.1.4. the membership number of the member;

15.1.5. the practice code number, group practice number and individual provider registration number provided by the registration authorities for providers, if applicable, of the supplier of service and, in the case of a group practice, the name of the practitioner who provided the service;

15.1.6. the relevant diagnostic and such other item code numbers that relate to such relevant health service;

15.1.7. the date on which on which each relevant health service was rendered;

15.1.8. the nature and cost of each relevant health service rendered, including the supply of medicine to the member concerned or to the dependent of that member, and the name, quantity, and dosage of, and net amount payable by the member in respect of the medicine;

15.1.9. where a pharmacist supplies medicine according to a prescription to a member or to a dependent of a member of the scheme, a copy of the original prescription, if required by the scheme...' (emphasis added).

By including the above italicised information in the account sent to Mr W's father, he will be able to determine the type of health services his son received and his health status. This situation contradicts Mr W's right to informational self-determination and information privacy. Although we appreciate that the board of any medical scheme 'must apply sound business principles and ensure the financial soundness of the scheme', which includes the rendering of detailed accounts, GEMS' scheme rules also clearly provide that all reasonable steps must be taken to 'protect the confidentiality of medical records concerning any beneficiary's state of health'.[21] In further appreciation of the fact that the rendering of such accounts is necessary for the performance of their medical scheme agreement with Mr W's father, we propose that the solution to this conundrum rests in the manner in which these accounts can be rendered to preserve the informational privacy of Mr W. By changing the rules of the scheme, the board of trustees can introduce technical privacy-preserving solutions to use when rendering accounts that could allow for patient-specific access.[21] In this regard, the Information Regulator reiterated section 19(1) of POPIA by confirming that any responsible party (medical scheme) must secure the integrity and confidentiality of personal information 'by taking appropriate, reasonable technical and organizational measures' to prevent unlawful access to personal information and to identify all reasonably foreseeable internal and external risks to personal information in its possession or under its control, and to maintain appropriate, effective, and up-to-date safeguards against such risks.[22] The Information Regulator pertinently states that responsible parties must have 'due regard to generally accepted information security practices and procedures' (emphasis added).1221 It can accordingly be expected that medical schemes implement the latest appropriate and effective privacy-preserving technologies to safeguard the health information of its members, including dependents such as Mr W.

Consumer rights

The practice of medicine is not only influenced by fundamental rights such as privacy and patient autonomy,[23] also by the fact that doctors and medical schemes are increasingly considered to be healthcare service providers to their patients and members, who are the consumers of healthcare.[24] As consumers demand greater control over their data, the delicate balance between protecting personal privacy and safeguarding consumer rights becomes ever more crucial. This consumerist model raises the concern that doctors, and medical schemes, may also relax their professional ethics in favour of more marketplace-oriented principles.

Mr W's father is considered to be a health services consumer who is the beneficiary of medical costs insurance provided by his medical scheme, irrespective of whether he was a party to the health services transaction concluded by between his son and his son's doctor, and is thus entitled to the protection offered to consumers in the Consumer Protection Act (CPA).[25] In addition to the obligation to render an account as provided for in the specific scheme's rules, as discussed above, section 22(1)(b) and 22(2) of the CPA stipulate that such an account must also be provided in plain and understandable language to the extent that an ordinary consumer, such as the main members of medical schemes, 'with average literacy skills', could understand its content. We have argued above that any person with 'average literacy skills' would be able to look up the meaning of specific ICD codes on the internet, or the specific medical practitioner to determine his or her field of expertise, and that these codes are not sufficient to protect the privacy of sensitive special personal information such as Mr W's HIV status, hence the need for technical privacy-preserving techniques to be introduced, as discussed above.

The control of transactional information constitutes one of the main pillars of consumer privacy.[26] Research in this regard found that if concerns about consumer privacy are not mitigated, it may negatively impact on consumers' decision-making, purchasing and trust.[27] Mr W, being a consumer of HIV testing services, may be loath to again make use of his medical aid because of the fact that his health information relating to such services would appear on the account rendered to his father. This may lead to him either pay for such services himself, or refrain from obtaining further health services in this regard, with possible detrimental consequences to his health and future relationships. Consumer privacy in the health insurance context accordingly proves to be both a critical business and healthcare issue.[28]

Consumer privacy is important, because privacy in this context helps to secure one's personal autonomy by allowing patients to take control and responsibility for their own lives.[29] Mr W would be more incentivised to seek HIV treatment if he was assured that his health status would remain private. Limits to or the specific structuring of private communication to others also allow people to set clear boundaries in interpersonal situations.[30] Communication of Mr W's HIV status to his father could have been limited through the implementation of technical privacy-preserving technologies, preserving both Mr W's privacy and his relationship with his father.

Companies often justify their control of consumer data based on utilitarian grounds, on which business practices simply deny the autonomy of the consumer.[31] However, health consumers often demand conflicting rights such as the right to privacy with regard to their health status, and the right to being informed about details of items they need to pay on an account. These rights increasingly conflict with companies' business or financial models.

Recommendations

• Section 61 of the MSA stipulates that the Registrar of Medical Schemes may 'declare a particular business practice as undesirable'. Subsequently, the manner in which accounts are rendered by medical schemes to members may be declared as an undesirable practice, and the registrar can prescribe certain methods and technologies that will allow for the safe and private rendering of accounts.

• Medical schemes may take the initiative to provide technical security measures to limit access to details stipulated in the account only to such individuals to whom they pertain personally, while still disclosing the amount to the main member.

• Research is necessary to focus on the operationalisation of consumer and informational privacy in the context of this article, including the factors that influence people's privacy concerns, and the company-level strategy to manage consumer and informational privacy.

• Further research should focus on finding effective methods of address privacy protection through the organisational structures of companies, and how these companies must adapt or modify their strategies to efficiently and effectively manage consumer and informational privacy in ways that benefit both the medical schemes and their members.

Conclusion

Like any other business, medical schemes are driven by business principles and financial models. To ensure that members pay any co-payments and are happy with the health coverage provided, they render regular and detailed accounts to the main member. These accounts contain specific information, including personal and special personal information, as determined by the scheme's rules, and allowed for by POPIA. However, the provision of special personal information of a financial dependent to the main member contradicts the dependent's rights to privacy and confidentiality. This unwanted disclosure of health information can lead to the deterioration of relationships among families, relatives, or work colleagues because of discrimination, and even pose an obstacle to further medical testing or treatment, to prevent such information from appearing on medical scheme accounts.

Sheehan and Hoy[32] found that the more sensitive a person considers information to be, the more the person will consider the impact of such information on their privacy, and the extent to which the person feels that such information, if disclosed, will harm them.[33] Information sensitivity also depends on each individual's situation. If Mr W's father worked in a different field or industry, or his parents were more liberal, then his sexuality or HIV status could have been less problematic for him to disclose to them.

Informational power and responsibility should be in equilibrium, where the more powerful party has the greater responsibility to ensure trust and confidence in the other party.[34] It is therefore important that one understands information privacy and the factors that influence people's privacy concerns such as cultural values, regulatory approaches, corporate privacy management styles, privacy problems and regulatory preferences. One of the regulatory preferences seems to be the implementation of privacy-preserving technologies to safeguard special personal information.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. Equal contributions.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. South Africa. Medical Schemes Act No. 131 of 1998.

2. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. ICD-11. The global standard for diagnostic health information. Geneva: WHO, 2022. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (accessed 4 April 2023). [ Links ]

3. Parbhoo T. Understanding ICD-10 coding and its usage. S Afr Dental J 2021;76(2):59-60. https://doi.org/10.10520/ejc-sada-v76-n2-a3.

4. O'Neill A. Literacy rate in South Africa 2015. Statista. 21 July 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/572836/literacy-rate-in-south-africa/ (accessed 4 April 2023).

5. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 8th ed. London: Oxford University Press, 2019. [ Links ]

6. Jansen van Vuuren and Another NNO v Kruger 1993 (4) SA 842 (AD).

7. South Africa. National Health Act No. 61 of 2003. Regulations: Surveillance and control of notifiable medical conditions.

8. Bratt v IBM, 467 N.E.2d 126 (1984); Bratt, et al. v IBM, 785 F.2d 352 (1986).

9. South African Medical Association. HIV/AIDS guidelines. Pretoria: SAMA, 2014 https://www.samedical.org/images/attachments/guideline-ethical-human-rights-aspects-on-hiv-aids-2006.pdf (accessed 23 February 2023). [ Links ]

10. South African Medical Association. Ethical and human rights guidelines on HIV and AIDS. Part A - general principles. Pretoria: SAMA, 2006. https://www.samedical.org/images/attachments/guideline-ethical-human-rights-aspects-on-hiv-aids-2006.pdf (accessed 23 February 2023). [ Links ]

11. South African Medical Association. Guidelines on maintaining patient confidentiality in wards. Pretoria: SAMA, 2014 https://samedical.org/images/attachments/guidelines-on-maintaining-confidentiality-in-wards-013.pdf (accessed 23 February 2023). [ Links ]

12. Skinner D, Mfecane S. Stigma, discrimination, and the implications for people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. SAHARA J Soc Aspects HIV/AIDS Res Alliance 2004;1(3):157-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2004.9724838

13. South Africa. National Health Act No. 61 of 2033. Section 14.

14. South Africa. Promotion of Access to Information Act No. 2 of 2000. Section 30.

15. Mallardi V. [Le origini del consenso informato1 (The origin of informed consent). Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2005;25(5):312-327.

16. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Section 12(2).

17. South Africa. Protection of Personal Information Act No. 4 of 2013.

18. Campbell A. Relationship marketing in consumer markets: A comparison of managerial and consumer attitudes about information privacy. J Direct Marketing 1997;11(3):44-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-7138(199722)11:3%3C44::AID-DIR7%3E3.0.CO;2-X

19. South Africa. Protection of Personal Information Act No. 4 of 2013. Sections 26 and 27.

20. South Africa. Medical Schemes Act No. 131 of 1998. Sections 29(1)(d) and 59.

21. South Africa. Government Employees Medical Scheme (GEMS). Medical Schemes Rules. GEMS, 2018. Rules 15, 19(25), 21(4), and 21(13). https://www.gems.gov.za/-/media/Project/Documents/scheme-rules/2021/Scheme-rules/a-2021-GEMS-Rules--Main-Body-vFINAL-CMSregistered-on-31-Jan-2018-Effective-from-31-Jan-2018.ashx?la=en (accessed 24 February 2023).

22. Information Regulator South Africa. Guidance Note on the Processing of Special Personal Information. 2021. https://inforegulator.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Guidance-Note-Processing-Special-PersonalInformation-20210628-004.pdf (accessed 17 March 2023).

23. Puras D. Human rights and the practice of medicine. Public Health Rev 2017;38:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0054-7

24. Rowe K, Moodley K. Patients as consumers of healthcare in South Africa: The ethical and legal implications. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14(1):14-15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-14-15

25. South Africa. Consumer Protection Act No. 68 of 2008. Definitions: 'consumer'.

26. Goodwin C. Privacy: Recognition of a consumer right. J Pub Pol Marketing 1991;10(1):149-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569101000111

27. Eastlick MA, Lotz SL, Warrington P. Understanding online B-to-C relationships: An integrated model of privacy concerns, trust, and commitment. J Bus Res 2006;59(8):877-886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.02.006

28. Margulis ST. Privacy as a social issue and behavioral concept. J Soc Iss 2003;59(2):243-261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00063

29. Shils E. Privacy: Its constitution and vicissitudes. Law Contemp Problems 1966;31(2):281- 306.

30. Simmel G. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. Glencoe: Free Press, 1950. [ Links ]

31. Foxman ER, Kilcoyne P. Information technology, marketing practice, and consumer privacy: Ethical issues. J Pub Pol Marketing 1993;12(1):106-119. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569501200111

32. Sheehan KB, Hoy MG. Dimensions of privacy concern among online consumers. J Pub Pol Marketing 2000;19(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.19.L62.16949

33. Phelps JE, D'Souza G, Nowak GJ. Antecedents and consequences of consumer privacy concerns: An empirical investigation. J Interactive Marketing 2001;15(4):2-17. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.1019

34. Milberg SJ, Smith HJ, Burke SJ. Information privacy: Corporate management and national regulation. Org Sci 2000;11(January-February):35-57. https://doi.org/10.10520/ejc-sada-v76-n2-a3

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M Botes

wmbotes@sun.ac.za

Accepted 23 June 2023