Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Bioethics and Law

On-line version ISSN 1999-7639

SAJBL vol.15 n.2 Cape Town Oct. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJBL.2022.v15i2.817

ARTICLE

Public health and the legal regulation of medical services in Algeria: Between the public and private sectors

T AlsamaraI; G FaroukII; M HalimaII

IPhD; Prince Sultan University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

IIPhD; Badji Mokhtar-Annaba University, Algeria

ABSTRACT

The article examines the issue of public health and medical services in Algeria and analyses the role of the public and private sectors in supporting and promoting public health. Our study is based on an analysis of legal texts that highlight Algeria's health policies. Some significant aspects of the article are: the Algerian policy of opening health services up to private investment; the lack of contribution of private health institutions in the field of medical education; and issues surrounding the organisation of blood donation. The article also notes the absence of foreign investment in Algerian hospitals.

Governments are involved in supporting the functions of healthcare institutions because of the direct relationship between government functions and the right to health as a human right.[1] The right to health is usually declared in state constitutional legislation.[2] Moreover, each state undertakes to fight pain[3,4] and epidemics in its territory.[5] But at the same time, states allow the private sector to be active in the health sphere for several reasons. The trend toward economic openness has encouraged states to open the medical space to private medical institutions. Globalisation has become one of the primary challenges confronting health policymakers in terms of health insurance and free treatment.

The importance of trade in health services cannot be overstated. Although little is known about how trade in health services affects population health and national economies, it provides an important supplement to public health institutions. The overall economic and trade context of a country is a key determinant of the impact of trade in health services. Another factor is the openness of a country's health sector to trade; however, little, if anything, is currently known about the best way to assess the impact of opening public health services to private sector activity.[6] Private health institutions aim to make a financial profit through health services provided to customers. This has given rise to in-depth discussions about the legitimacy of health services being handled by private institutions.[7] Scientific debate has concluded that private health institutions are subject to ethics and law.[8]

This study aims to explore the impact of Algeria's economic transformation from a socialist system to a capitalist system. Tambor et al.[9] conducted a study of the changes in healthcare systems in several European countries after the fall of the communist regime. The authors investigated the role of the government and households in healthcare financing in eight European Union (EU-8) countries: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. Where the state has abandoned funding for health institutions, the result has been serious violations of the population's right to health in those countries. To collect quantitative data on healthcare expenditures and qualitative data on gaps in universal healthcare coverage, the literature search method was used. The trend in health spending from 2000 to 2018 was examined using linear regression analysis.[9]

Djeddi[10 ] in his research on health policy in Algeria concluded that changes in political perceptions of the state of healthcare in Algeria, are associated with local political and economic factors on the one hand, and international developments in health policy on the other. Algeria must face its healthcare challenges within this national and international context: fighting epidemics that endanger the lives of people in remote areas of the country; and establishing research centres to develop medical competencies in the areas of diabetes and chronic diseases and reduce the country's deficit in these areas. Djeddi also noted that Algerian citizens are not required to pay for medical treatment abroad in France, where they can travel for healthcare services not available in Algeria.

For more specific details we refer to Scherer's[11] research comparing healthcare challenges in Algeria, Brazil and France. In this study description and analysis are divided into three sections: the context and trajectory of health systems; hospitals and emergency services; and the challenges that must be overcome. Interviews, surveys and observation were used in the research. The data were analysed using participatory appraisal techniques associated with source and data triangulation. The following issues were identified as major challenges: a lack of hospital beds in inpatient units; a lack of infrastructure and materials; an excess of chronophagic (i.e. 'time-wasting') activities; generational transitions; and violence by patients and families. Despite their differences, all three countries face similar challenges. Due to low levels of public funding, measures to rationalise and reduce spending have a greater impact in Algeria and Brazil, but they also occur in France. In the medium term, measures to reduce loss of productivity owing to time-wasting activities, material shortages and violence should be considered to improve emergency response work.

In another article, Mrabet et al.[12] discuss the effects of aspects of the quality of healthcare services on patient satisfaction in the Algerian private sector. After the application of structural equation modeling, the results revealed that the following factors were significant in contributing to patient satisfaction: reliability, tangibility, credibility and responsiveness of the healthcare service. However, empathy with the patient was not found to be a significant factor. This suggests that patients have a positive perception of the quality of the healthcare service if they feel it reflects the listed positive factors, even if they feel the healthcare provider is not empathetic towards them. Healthcare practitioners can use this model to assess healthcare and improve service quality.

In an empirical study conducted in Algeria, Amroune and Dib[13] investigated the impact of healthcare spending on achieving sustainable development goals, from an econometric standpoint, focusing on the third goal: good health and well-being in Algeria, which was represented by the rate of hope in life. Data from the study spanned 29 years, from 1990 to 2018. These data were processed using multiple regression analysis techniques, and the estimation was made using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method. The study found that the variables of state and National Social Security Fund spending have a positive effect on improving the level of hope in life, whereas the variable of private family contributions to health spending has a negative effect.

The public nature of health services during the socialist period

Algeria adopted a socialist approach to the general health sector after its independence. The first post-independence legal text was Ordinance No. 73-65 dated 28 December 1973, which declared the establishment of free medicine in the health sector. This text includes a lengthy preamble stating the legislator's justifications for turning to socialism in the general health sector, and the state's commitment to financing the health sector, including the provision that health services related to diagnosis and treatment in hospitals should be free of charge. The aim of free treatment was to make the right to health more accessible to citizens. The legislator's view of healthcare is reflected in Law No. 85-05 of 16 February 1985, on the protection and promotion of health, which emphasised the control and promotion of the public sector in healthcare (Article 5 of Law No. 85-05). Article 20 indicated that the public sector is the basic framework that provides free treatment. The state also committed, under this law, to provide all the necessary facilities to protect and promote health through free treatment. During this period, the private sector was not allowed to establish private hospital institutions. Private sector doctors were only allowed to work in the fields of dentistry, pharmacy, medical analysis laboratories, medical optics, eyeglass laboratories and reconstructive laboratories (Article 208 of Law No. 85-05).

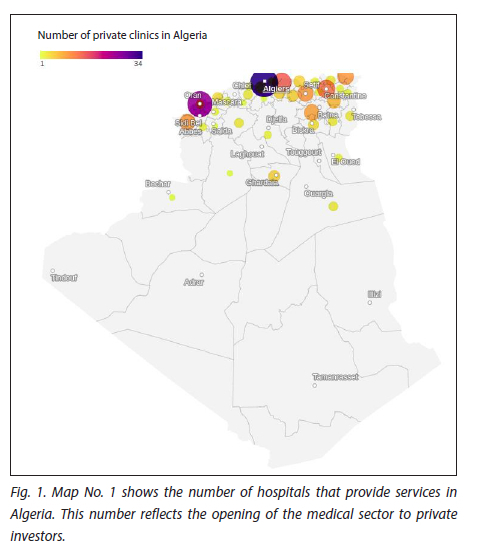

The following public health institutions can be found in Algeria: university hospital institutions; university hospital centres; specialised hospital establishments; public hospital institutions; public institutions for neighbourhood health; and care units. Each type of institution has a legal framework that regulates its work and defines its validity. In 2013 the number of public health institutions was estimated at 282 hospitals, 1 627 polyclinics and 5 484 care units.[13]

Private health institutions

Private health institutions are defined as research, treatment and hospitalisation institutions related to human health (Article 305 Health Law 2018). Upon its establishment, a private health institution is subject to the standards specified in the health map, as well as to the priorities specified in the health regulation plan, and to the technical conditions specified by the Minister of Health (Article 306 Health Law 2018). A licence is required from the Minister of Health for the establishment, opening, use, expansion, transfer, closing and total or partial change of each private health structure or institution (Article 307 Health Law 2018). The health regulation plan oversees the health activities of health professionals, especially in private hospital establishments; private treatment institutions; individual practice structures; collective practice structures; pharmacies; pharmaceutical institutions; medical analysis laboratories and approved structures for health transport (Article 308 Health Law 2018).

The Algerian Health Code allows natural persons and legal persons to establish and make use of private health institutions (Article 309 Health Law 2018). The task of the public service can be temporarily assigned to private health structures and institutions under certain circumstances, to provide equal access to treatment by ensuring permanent health coverage in areas where health coverage is insufficient, based on the implementation of national and regional health programmes (Article 311 Health Law 2018). Public health services may be assigned to private health institutions through an agreement concluded with the Ministry of Health.

The contribution of private pharmacies to the elimination of the COVID-19 epidemic

Fighting diseases, avoiding the emergence of an epidemic and eliminating the causes of the epidemiological situation are among the basic tasks of public state institutions. With the COVID-19 pandemic, radical amendments were made to the Health Law for 2020, in particular with regard to pharmacies, due to the fact that private pharmacies effectively assisted in combating the emerging COVID-19 virus by conducting PCR analyses and contributing to the vaccination campaign. In this context, the Ministry of Health has developed a guide for pharmacists that explains the conditions for conducting this process in detail.

Conditions for the establishment of a private hospital

To establish a private hospital, a licence is required from the Minister of Health based on an administrative and technical file deposited with the relevant state department. In addition to the documents required for construction, plans and a detailed description of the project, the location, activities and works to be carried out must be provided, and a deposit receipt is delivered to the project owner. A private hospital institution must meet various architectural conditions and standards to be granted this licence (Executive Decree No. 07-321 of 24 October 2007, regulating and operating private hospital establishments, Official Journal No. 67 of 24 October 2007).

These conditions and standards have been amended several times. Currently they are as follows: The location of the private hospital must comply with any standards facilitating the preservation of the environment and must take into account the proximity of public transportation facilities. Private hospital establishments must comply with all standards of construction, comfort, hygiene and security following applicable legislation and regulations. They should also include the necessary features to facilitate the access of persons with special needs to the various structures and interests of the institution. Private hospital establishments must be completed while respecting the architectural plans approved by the technical departments of the Ministry of Health, Population and Hospital Reform in accordance with the architectural terms and standards specified in the model book of conditions, (Articles 2 to 4 of the Ministerial Decree of the Ministry of Health Population and Hospital Reform No. 11 of 6 February 2016, specifying the architectural, technical and health conditions and standards for private hospital establishments).

Inspection by public authorities of health institutions in the private sector

The Algerian Health Code establishes the oversight of public authorities over private health institutions, which are subject to the monitoring and evaluation of the competent departments of the Ministry of Health (Article 310 Health Law 2018). Private health institutions are required to fulfill the conditions set out in the requirements manual as determined by the Minister of Health. The requirements manual lays out conditions for providing public service, the type of health services to be provided and the timeframe for the agreement of services (Article 311 Health Law 2018). The Algerian legislator enforces a penalty for private health institutions, where the operating licence can be withdrawn temporarily or permanently if the organisational conditions of management are not met; laws and regulations for private health institutions are violated; or where the institution has failed to ensure the security of patients (Article 314 Health Law 2018).

The commercial nature of private hospital institutions

Article 208 of Law 058-15 did not allow the operation of private clinics except by joint ventures and non-profit associations, but this has been amended with the issuance of Order 06-07. Private hospital institutions are now included in commercial companies, where they can be operated by persons with sole proprietorship; limited liability companies; joint-stock companies; joint ventures and associations. It is mandatory for a private hospital institution to have a medical technical manager (Law 05-85, Law 15-88, Order 06-07). After the public sector had dominated healthcare in Algeria for several years, the space was gradually opened to the private sector, with the amendment of the Health Law of 1985. The amendment allowed the establishment of clinics in the private sector and stipulated that medical activities must be practised by private individuals in hospital clinics; medical examination and treatment clinics; dental surgery clinics; pharmacies; and optical laboratories (Article 208 of Law 85-05 under Law 88-15). Article 208 was subsequently amended by Law 06-07 of 2006, to include 'private hospital institutions.' The change from the term 'hospital clinics' to the broader term 'hospital institutions' is evidence of the expansion of the activity of private facilities and their increased absorptive capacity. Furthermore, Law 18-11 affirmed the contents of Article 308, stating that health activities practised specifically by health professionals are guaranteed; especially in private hospital establishments; private establishments for treatment or diagnosis; individual practice structures; collective practice structures; pharmacies and pharmaceutical establishments; medical analysis laboratories; and approved structures for health transport.

Private health sector support of public health sector in obstetric services

To reduce the burden on public hospital institutions in the field of obstetrics, the Algerian government issued Executive Decree 20-60 allowing births to be handled by private clinics, thereby promoting co-operation between the public and private health sectors in this field. The decree sets out the conditions for undertaking caesarean and regular deliveries in private hospital clinics. It also specifies the conditions for preparing the agreement between the National Social Security Fund and the private clinic. The legal representative of the clinic is required to submit a complete file, including a copy of the licence from the Ministry of Health allowing the opening of the institution; a special card outlining the clinic's equipment and features; a list of the names of all medical staff; and a certificate of payment of contributions. The owner of the clinic must have a document prepared by the fund certifying that the relevant public institution will ensure the appropriate removal and treatment of medical waste. The decree also stipulates, as a prerequisite for concluding the agreement, that deliveries be supervised by a suitable gynaecologist who performs their duties at this level full time. With regards to compensation, the decree set a deadline of 30 days as a maximum limit for paying fees due to private clinics, from the date of receipt of the invoice. To take advantage of the privileges approved by the new decree, the insured party must submit a request for insurance during the month preceding the presumed date of birth and include a medical report from the treating physician specifying the presumed date and nature of the birth.

The monopoly of public health institutions on blood donation activities

A specialised national agency oversees blood donation activities in Algeria.[15] The National Blood Agency, established in 1995 and reporting to the Minister of Health, is in charge of ensuring a safe, adequate and sustainable supply of blood products in order to meet the national need for blood, which is in constant demand due to increased life expectancy and innovations in quality of healthcare.[15] It is important to note that private healthcare facilities are not permitted to collect blood donations, which fall under the exclusive mandate of the government agency. This exception arises due to the voluntary nature of blood donation, which conflicts with the goal of private health institutions to make a profit. As a result, private health institutions have had to rely on public health institutions in cases where patients require blood transfusions. Specialised healthcare institutions both within Algeria and internationally have advocated for voluntary and uncompensated blood donation through various statements, blogs, recommendations and guidelines. A few countries allow donors to be reimbursed for activities related to blood donation which inevitably incur costs, such as transportation. Legislation in some countries may even allow trade in certain types of human biological materials, and the use of voluntary human blood donations to create products that are then marketed.[17]

Absence of contribution by private health institutions to higher medical education and capacity building

It is important to emphasise the dominance of public health institutions in the medical training sphere in Algeria.[18] Algeria currently has no private health institutions providing higher medical education, and there is no private university at which to study medicine. Medicine is only taught at universities in provinces which have a university hospital centre. As a result, it is critical to consider how to encourage private individuals to invest in institutions for higher medical education.

Absence of foreign investment in health institutions

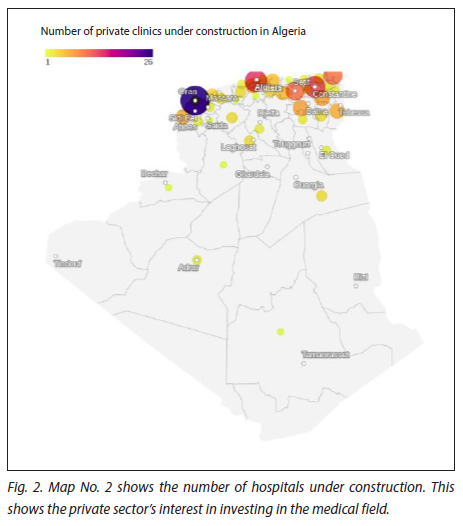

The absence of foreign investment in the health sector is noticeable. In contrast to the pharmaceutical industries, which attract numerous foreign investors, Algeria has very few private hospitals backed by foreign capital.[19,20] The Algerian government is currently taking steps to increase foreign investment in the health sector.

Conclusion

The article aims to study the co-ordination of health services between the public sector and the private sector in Algeria, noting the dominance of the public sector despite the availability of free treatment. The private sector is encouraged to support the state's efforts in the field of higher medical education and capacity building, through the establishment of private universities that teach medical professions. Finally, the absence of foreign investments in the field of medical services is noted.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. All authors of this article would like to thank the Governance and Policy Design Research Lab (GPDRL) of Prince Sultan University (PSU) for the financial and academic support to conduct this research and publish it in Sustainability Journal.

Author contributions. Equal contributions.

Funding. Prince Sultan University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Tobin J. The Right to Health in International Law. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012:7-10. [ Links ]

2. Soohoo C, Goldberg J. The full realization of our rights: The right to health in state constitutions. Case W Rsrv L Rev 2009;60:997.

3. Brennan F, Carr DB, Cousins MJ. Pain management: A fundamental human right. Anesth Analg. 2007;105(1):205-221.

4. Cousins MJ, Brennan F, Carr DB. Pain relief: A universal human right. Pain 2004 Nov;112(1-2):1-4.

5. Sirleaf M. Responsibility for epidemics. Tex Law Rev 2018;97:285-354.

6. Smith R. Measuring the globalisation of health services: A possible index of openness of country health sectors to trade. Health Econ Policy Law 2006;1(4):323-342.

7. Blumenthal D, Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents - The evolving Chinese health care system. N Engl J Med 2005;353(11):1165-1670.

8. Cetina I, Dumitrescu L, Pentescu A. Respecting consumer rights and professional ethics: Particular aspects of the Romanian healthcare services. Contemp Read Law Soc Justice 2014;6(1):462-472.

9. Tambor M, Klich J, Domagata A. Financing healthcare in Central and Eastern European countries: How far are we from universal health coverage? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(4):1382.

10. Djeddi A. The Health Policy in Algeria (Facts and Challenges). Hayatsaglik Dergisi (Life Health Journal) July 2017. No. 16. Special Issue:12-19.

11. Scherer MD, Conill EM, Jean R, et al. Challenges for work in healthcare: Comparative study on University Hospitals in Algeria, Brazil and France. Cien Saude Colet 2018;23(7):2265-2276.

12. Mrabet S, Benachenhou SM, Khalil A. Measuring the effect of healthcare service quality dimensions on patient's satisfaction in the Algerian private sector. Socioeconomic challenges 2022;6(1):2520-2662.

13. Amroune A, Dib K. The impact of spending on health care economics in achieving sustainable development goals: An empirical evidence-case of Algeria during the period 1990-2018. Rev Organ Trav 2021;10(1):255-270.

14. Chikhi SM, Kicha DI, Tadjieva AV. Development of primary health care in Algeria. RUDN Journal of Medicine 2016(3):75-82.

15. Ministry of Health, Republic of Algeria. https://www.sante.gov.dz/services/ehp/82-documentation/1086-ehp-fonctionnels.html (accessed 22 September 2022).

16. Hmida S, Boukef K. Transfusion safety in the Maghreb region. Transfusion Clinique et Biologique 2021;28(2):137-142.

17. Tahri H. The health situation in Algeria during the period 1990-2018. J El-Ryssala Stud Res Hum 2022;7(4): 850-859.

18. Petrini C. Between altruism and commercialisation: Some ethical aspects of blood donation. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2013;49(4):412-416.

19. Boussalem F, Boussalem Z, Taiba A. The relationship between public spending on health and economic growth in Algeria: Testing for co-integration and causality. Int J Bus Manag 2014;2(3):25-39.

20. Alsamara T, Farouk G, Adel A. Public health and the legal regulation of the pharmaceutical industry in Algeria. Pan Afr Med J 2022;41:86.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

F Ghazi

ghazifarouk1@gmail.com

Accepted 1 September 2022