Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Bioethics and Law

versão On-line ISSN 1999-7639

SAJBL vol.15 no.1 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJBL.2022.v15i1.765

ARTICLE

Midwives' ethical practice in selected labour units in Tshwane, Gauteng Province, South Africa

J M Mathibe-NekeI; M M MashegoII

IMMed (Bioethics and Health Law), PhD; Department of Health Studies, School of Humanities, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

IIposthumous), MA Nursing Science; Medical Unit, George Mukhari Hospital, Ga-Rankuwa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Midwives provide the majority of maternal and child healthcare in South Africa (SA). The care provided by midwives during childbirth is a unique life experience for women, and in order to provide safe care, midwives are expected to comply with ethical principles, policies and legislation governing their profession, as guided by the International Confederation of Midwives.

OBJECTIVE. To establish midwives' perception of ethical and professional practice in selected labour units of public healthcare, in Tshwane District, Gauteng Province, SA.

METHODS. A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive cross-sectional design was applied by use of in-depth interviews. Non-probability purposive sampling was used to draw a sample from midwives with 2 or more years of experience working in the labour units. Data saturation was reached with the eighth participant. The digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data analysis was based on interpretive description.

RESULTS. The findings revealed that midwives do understand the ethical code of conduct. They experience challenges such as staff shortages, non-compliance with policies and lack of managerial support, which compromise ethical conduct to a certain extent.

CONCLUSION. It is hoped that the suggested administrative, midwifery practice and research recommendations will guide the process of empowering midwives in ethical practice.

Recently, South Africa (SA) has experienced several serious adverse events in labour units, which have often led to litigation by the SA Nursing Council (SANC). In 2011, the Minister of Health released the number of lawsuits already paid by the various provincial departments of health, amounting to ZAR1.7 billion in the past 7 years, related to gynaecology, midwifery and surgical procedures, of which ZAR100 million was for the Gauteng Department of Health. All these lawsuits were related to obstetric malpractice, as stated in City Press.[1] Furthermore, in 2014, the Sunday Times of 17 January released a statement that revealed that the Gauteng Department of Health had received 306 negligence claims totalling ZAR1 286 billion, of which 155 claims were for childbirth.[2]

Midwives working in labour units are confronted with ethical decision-making. There is always fear around the baby not being safely delivered or the mother presenting with complications, as alluded in a study conducted by Hood et al.[3] on scrutiny and fear about the experiences of Australian midwives. The study revealed that midwives' perception of the work environment is driven by fear of litigation.

Midwives, as professional nurses, are expected to provide quality care to women who rely on their expertise. However, the findings of a study on exploring nurses' personal dignity, global self-esteem and work satisfaction by Sturm and Dellert[4] led to a finding that professional nurses' satisfaction with their practice environment influences the quality of patient care and outcomes. Furthermore, the authors stated that when nurses are overworked, quality care may be jeopardised. Nyathi and Jooste[5] corroborate these findings by indicating that increased workload leads to low morale, which may lead to low standards of care, and that any midwifery practice that falls below the required standard of a professional is considered malpractice.

In circumstances where malpractice has occurred, legal action may ensue, as stated by McHale and Tingle.[6]

Arries[7: conducted a study that led to the formulation of practice standards in ethical decision-making, with reference to the SANC's disciplinary reports on cases of unprofessional conduct. The study highlighted the fact that midwives' and nurses' clinical decision-making were ineffective owing to non-adherence to the framework of ethical and legal practice.

As stated by Kulju et al.,[8] ethics is considered fundamental in healthcare, and ethical competence forms part of professional practice characterised by respect, honesty and loyalty to patients. Furthermore, midwives are required to make sound ethical decisions in their daily practice, and to demonstrate competence in handling and resolving ethical dilemmas. As part of ethical competency, Ito and Natsume[9: highlight the point that ethical dilemmas need a critical analytic mindset and problem-solving skills, for example, weighing between the right to self-determination v. confidentiality, distributive justice and privacy.

Kinnane[10]: explains that during each ethical encounter, there are opportunities for good or bad decision-making. However, the focus should be on a decision that is in the best interest of the patient.

As stated by the International Confederation of Midwives code of ethics,[11] one crucial element is that midwives carry responsibility and accountability for midwifery practice. The midwife is therefore mandated by the code of ethics to provide an ethically acceptable standard of practice.

As stated by the SANC,[12] competencies are a combination of knowledge, skills, judgement, attitude, values, capacity and abilities that underpins effective performance in a profession. The midwife is therefore considered competent if (s)he has the ability to integrate and apply the knowledge, skill, judgement, attitude and values required to practise safely and ethically in a designated role or setting. A study on legal and ethical aspects of midwifery care by Waghmare[13] revealed that the majority (80%) of midwives had moderate knowledge, and only 20% had adequate knowledge of legal and ethical aspects of midwifery care.

Objective

The researcher, who has experience with the investigation of malpractice, has observed a variety of emotions displayed by midwives during disciplinary hearings held by the SANC. Though policies and guidelines for maternity care are available in SA, little is known about whether midwives perceive or understand the ethical and malpractice issues within labour units. Therefore, this study aimed to establish midwives' perceptions of ethical and professional practice within selected labour units in Tshwane District, Gauteng Province, SA.

Methods

A qualitative, exploratory, descriptive and cross-sectional design was applied using a phenomenological approach,[14] which investigated midwives' subjective understanding and experiences regarding ethical practice. Cross-sectional data were obtained in a single brief period. The labour units were randomly selected among labour units that had a history of practitioners who had appeared before the SANC with pending litigation, and participants were purposely selected in those particular labour units.[15,16]

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Health Studies Research Ethics Committee of the University of South Africa (ref. no. REC-012714-039). Permission to conduct the study was sought from the institution and labour units management.

Participants were informed of the study purpose and the methodology to be followed. Participation was voluntary, as supported by a signed informed consent. Participants were offered an opportunity to withdraw from the study at any point without any recourse. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the data collection process and reporting. [141

Trustworthiness

For dependability and confirmability, the study was supervised by a seasoned researcher who had conducted numerous qualitative research studies and published in accredited journals. Credibility was ensured through adhering to the research process and the measures taken to gain the trust of the participants, provision of a conducive and private environment for data collection, the capturing of nonverbal communication from participants during the data collection process and a thick description of the research report.[171 Prolonged engagement and member checks were applied to ensure credibilityof data.[14]

Data collection

In-depth interviews were conducted with midwives working in the randomly selected labour units. Data were collected in a private room that is part of the labour unit to ensure a conducive environment.[171 The interviews were recorded as per informed consent. A semi-structured interview guide was used. Data saturation occurred with the eighth participant.[14]

Data management and analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data analysis was initiated during interviews and continued throughout the process, up to the transcription of recorded data.[181 An inductive analysis and creative synthesis data analysis strategy was applied, where the researcher was immersed in the details and specifics of the data to discover important patterns and themes as they emerged. Interpretive description of the data was applied."[14]

Results

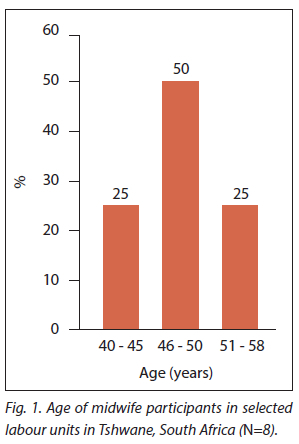

Demographic characteristics Age

As reflected in Fig. 1, all participants were of average professional middle age between 40 and 58 years, which implies advanced work experience.

Level of education

All participants held a Diploma in Nursing (general, community, psychiatry) and midwifery. Seven participants (88%) held an advanced midwifery training qualification. Advanced midwifery is a qualification designed to train a midwife who provides scientific, safe and comprehensive midwifery care within the legal and ethical framework, as stated by the SANC.[191 These midwives are specialists, as they function at a higher level than those with basic midwifery training. The level of education indicated that most participants were highly qualified.

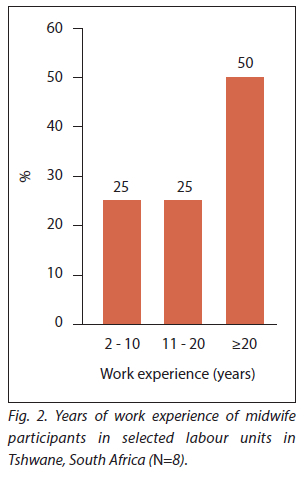

Work experience

Four of the participants had more than 20 years' experience of working in the labour units, two had 11 - 20 years of experience, one participant had 8 years and one 2 - 3 years of experience. Most participants had extensive experience of working in labour units (Fig. 2).

Thematic analysis of findings

Thematic analysis led to four major themes and sub-themes being identified, as illustrated in Table 1. The eight participants are coded P1, P2, P3, etc. for the purpose of presenting the findings.

Ethical and professional practice

Understanding ethical practice: Participants displayed an acceptable level of understanding of ethical practice, as reflected in their responses:

' Ethical practice is based on rules and regulations prescribed to us by our institutions, district health and South African Nursing Council and if not followed we end up with an omission.' (P4)

'I can say ethics involves rules and regulations, protocols and it includes professional standards that a midwife must adhere to.' (P3)

Rich and Butts[20] state that ethical behaviour is more than simply a feeling, but rather a moral code or set of values. As stated by participants, ethics is regulated by the International Council of Nurses[11] and the SANC[21]

A code of ethics is described by the SANC as a tool that serves as a foundation for ethical decision-making.[21] Smith and Godfrey[22] claim that women operate differently from men (as stated by Gilligan and others), as women evaluate an ethical encounter according to the ethic of care, which emphasises mutual interaction, responsibility and accountability between the midwife and the woman.

Accountability and responsibility:

Griffith[23] affirms that the midwife-woman interaction gives rise to a duty of care, as supported by deontology as a moral theory. There was an indication that participants know what is expected of them and how they should conduct themselves as professionals: 'Ethics refers to the accountability and responsibility, things that you are supposed to do as a midwife. There's a certain way a midwife should conduct herself, and there's an image that you must uphold. And you are answerable to the employer and the community that as a midwife, you need to preserve life. You need to conduct yourself in a certain way not to take your profession and the nursing into disrepute, don't take the dignity of the nurses down.' (P8)

Failure to adhere to practice standards:

According to Erasmus,[24] nursing malpractice exists because it is human to err under stressful conditions. The participants displayed their understanding of malpractice as follows:

'Malpractices are the wrong practices that need to be corrected, they are wrong practices like failure to give treatment or omission to give care to a woman in labour. When there is a malpractice, it constitutes an adverse event even if not serious, but you can be taken to a disciplinary committee for a hearing.' (P7)

Another participant stated:

'Malpractice is doing things not in the way it is supposed to be done, not rendering p tient care, and not treating clients correctly.' (P2)

' Malpractice is when as a midwife I don't practice according to the code of conduct, set standards and not rendering quality patient care.' (P3)

The above is supported by Klebanow,[25] who refers to malpractice as an undesirable activity, a negligent behaviour displayed by a professional who provides unsatisfactory service to the healthcare recipient.

The experience of ethical practice

Participants shared both positive and negative experiences of working in labour units.

Noble and fulfilling:

One participant stated: 'It is a blessing and is fulfilling to be a midwife.' (P6)

Another said: 'It is not good or bad, some cases are discouraging, and some are positive, it gives me that satisfaction working with the community, although there is shortage of staff and it's a high stress environment'. (PI)

Challenging and stressful: Participants also explained the challenges they faced:

'To be a midwife is a stressful career because you are working with two lives, the mother and the baby, so is two lives that depend on you and you must make sure that you save both lives.' (P5)

Participants further highlighted frustrations:

'In midwifery you deal with two lives, and we are not allowed to be human, we are supposed to be God and never say anything even if the woman is not co-operating during delivery some patients come with negative attitude and it's frustrating.' (P3).

Lewis[26] supports the above statement by highlighting how being a midwife involves tremendous acts of generosity, kindness and care, in which midwives support women and their families in intimate and often difficult and demanding situations.

Dilemmas in decision-making: Arries[7] affirms that decision-making is a critical component of healthcare practice, and that any decision has an impact on the lives of patients. To enhance the quality of these decisions, one should apply the four ethical principles of self-determination, beneficence or 'duty to do good', non-maleficence, which is a passive principle aimed at avoiding harm, and justice, which addresses equality and the rights of healthcare recipients, specifically in the context of this study, access to healthcare, and human and resource allocation.

This study revealed that in some cases, midwives make ethical decisions, but the patient may hinder the implementation of the decision, as illustrated in the following example: '[A1 patient refused to take anti-retroviral therapy stating that her pastor told her that she was healed of HIV, and she refused to take treatment and when the baby was delivered she also refused to participate in the PMTCT [prevention of mother-to-child transmission] programme after the baby was born and nevirapine was not administer medication to the baby.' (P5)

The researchers' viewpoint was that in this type of a situation, the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005[27] needs to be applied in order to cater for the rights of the baby. It was doubtful that the baby would be given the treatment at home, since the mother had demonstrated non-compliance. The mother was referred to social workers under the guidance of the unit manager.

Other challenges were reported as follows:

'[A] young girl (19 years) came to the facility being in labour and after delivery she did not want to breastfeed or touch the baby and then she mentioned that she was raped and didn't report at home that she was raped by a family member. It was an ethical dilemma for me and I ended up having to involve the mother and the social workers.' (P7)

With reference to autonomy or self-determination, the young woman had the right to make an informed decision and not be forced to breastfeed, especially as she was >18 years old. The midwife had a duty of confidence, but in this case had to intervene so that the mother of the 19-year-old was informed. Griffith[28] asserts that the duty of confidence is not absolute, and one has to reflect on the risk-benefit ratio. Griffith[281 further highlights that it is essential that midwives understand the extent of the duty to care that they owe women as a form of a social contract.

Professional conduct and image: According to Erasmus,[24] ethical practice entails acting from a sense of moral duty upheld through honouring one's obligations and respecting other peoples' rights. Midwives have a duty to do good (beneficence) and a duty to not do harm (non-maleficence) towards patients in their care. These principles mean that midwives must be careful when making decisions to avoid physical, emotional and psychosocial harm to the woman in labour, as also expressed by one of the participants:

' There is an image that you must uphold as a midwife, conduct yourself in a professional way and not take the profession into disrepute and you have to be accountable and responsible to your actions.' (P8)

A study on the evaluation of moral reasoning in nursing education by McLeod-Sordjan[29] showed that professionalism and ethical practice are symbiotic, as professionalism is rooted in ethical knowledge and moral reasoning skills as framed by the midwifery code of ethics.[11] As one participant said:

As a midwife I am expected to behave in a professional manner, treat my patients well and not with attitude, regardless of the situation.' (P6)

Poor decision-making: Participants associated malpractice with

poor decision-making: 'We assess every woman that comes and refer to the doctor, maybe in the clinics it can be said but it might be associated with poor decision-making but not in the hospital, mainly because in the clinic there are midwives only and if the decision is wrong, there is no one to correct you unless you phone the hospital for an opinion.'

Poor decision-making was also related to failure to advocate for patients:

'It sometimes happens that you make a decision thinking that you are making a good decision but only to find out that you are making a wrong decision. For instance, I had a case where a patient was referred to hospital because of polyhydramnios and preterm labour and then the emergency medical staff [EMS] were called, and when they arrive, the mother was fully dilated, and they refused to take her because they said she was going to deliver on the way, then the mother delivered at the clinic and the baby was so small a preterm and very distressed. It was very stressing and the EMS could not take preterm baby because the ambulance had no facility and the maternal obstetric unit also did not have the facility nor the equipment to cater for the needs of a preterm baby and the said baby died, if I had insisted that the mother be transferred maybe the baby would had survived.' (P2)

'Failure to administer magnesium sulphate to a patient with gestational hypertension [...] delay in referring patient to hospital and mother delivering a fresh stillborn and failure to advocate for the patient and the woman delivered alone in an ambulance without an escort.' (P4)

With regard to regular application of the ethics of care to nursing practice, Lachman[30] refers to Watson's caring model that requires the midwife to acknowledge the uniqueness of the pregnant woman and to try to preserve her dignity by applying the elements of caring as attentiveness, responsibility, competence and responsiveness that will ultimately enhance ethical practice. Participants further highlighted that:

'Yes, sometimes we make wrong decisions as midwives, in our MOU [maternal obstetric unit] a woman with low HB [haemoglobin] came in with ruptured membranes, according to the clinic notes she was supposed to deliver in hospital, she was told to go to hospital as she said she has transport. However, the woman did not have transport and went outside whereby she delivered by herself, and this was a poor decision because the patient was not properly assessed.' (P8)

A study conducted by Hood et al.[31] in Australia on midwives' experiences of obstetric services revealed that midwives are driven by fear of litigation that often impacts on an ideal decision-making process. Lewis[26] supports the above statement by highlighting that there is a hidden undesirable side of midwifery practice, as the main accountability is not healing but saving the woman and the baby's lives.

It is during these difficult and challenging situations that midwives often feel alone, as reflected in the following narrative: A woman presenting with labour pains and had big abdomen came to the clinic, she was not referred to the hospital, she had shoulder dystocia and after the struggle to deliver the baby, the patient started bleeding profusely and was sent to hospital in a very critical and compromising condition.' (P4)

Litigation experiences

Negligence: Most participants had gone through the experience of having been reported for negligence or failure to make an ethical decision, of which they were found not guilty: ' I once found a patient with meconium aspiration waiting for an ambulance which delayed for 3 hours and patient delivered a fresh stillborn, incident was reported to the quality assurance committee and the investigations concluded that the adverse event was due to transport-related issues.' (P7)

' I was charged with failure to advocate for the patient who was referred to hospital and deliver alone in an ambulance on way to hospital just 5 minutes away from the clinic.' (P1) Another participant shared the following: 'I was taken to a disciplinary hearing by the Department of Health and also by the regulating body SANC for failure to assess the fetal and maternal conditions properly, failure to advocate for the pregnant woman in labour and patient was discharged to go to the hospital but delivered alone outside the clinic premises and I was suspended for six months and I did my sentence.' (P8).

Klebanow[25] supports the above findings, saying that the most common types of omissions involve failure to diagnose and poor follow-up care.

Giving of evidence: One participant reported the following: As an operational manager, I am often requested to give report every time there is a serious incidence.' (P6)

Another participant indicated that: 'Most of the time when there is a malpractice error, we are called to write statements and matters are often internally resolved'. (P2)

The impact of malpractice and litigation

Frustration and demoralisation: Participants expressed the impact

of litigation as follows: ' You can't even work, you feel frustrated, it is demoralising, you feel demoted when there is malpractice in your ward, you are frustrated, afraid of touching a patient because thinking you might repeat the same malpractice, won't take decisions to discharge patients, especially if you facing a litigation involving discharging and referrals, you feel like resigning and there is low staff morale which leads to absenteeism.' (P2)

' But we don't do that anymore, we are afraid to take decisions because of fear of litigations ... we are afraid to be that independent practitioner we used to be, you always need someone to help, to take decision for us' (P8)

Litigation also led to low staff morale: ' It is very painful, it is demoralising, and you will feel that you are not effective and efficient as a midwife, and you become stressed, it can even affect your health.' (P1)

' Fear of touching patients, there is a fear factor and thinking that you will get involved in another adverse event and have another law suit.' (P5)

'Low morale leads to absenteeism which then leads to shortage of staff, and where there is shortage you look at more patients being one and mistakes do happen. Sometimes you become alone and if you deliver a fresh stillborn [FSB1, nobody wants to touch the FSB because they afraid to write statements.' (P4)

Frustration, discouragement and demoralisation further led to fear in

making ethical decisions: 'There is fear of making decisions as those under litigation are not willing to work because of fear of having another malpractice and this increase the work load on the one who has no litigation case. This leads to midwives who are not involved in the litigation to be also discouraged to work under fear.' (P8)

This fear was shared by most participants, as follows:

'It affects us badly because now as I am saying midwives are afraid to take decisions, like when you do a per vaginal examination on a woman and you find that she's 1 cm then you sent her home and tell her she'll come back when the pains are stronger, you have got transport you can come back later because our labour ward is too small is eight-bedded ward.' (P2)

Hood et al.[31] conducted a study on scrutiny and fear, and their findings revealed that midwives are driven by fear of litigation and feel exposed and not supported during legal proceedings.

Reduced confidence: Lack of confidence as a result of being

demoralised was also evident: 'It results in lack of confidence, I feel I let my community down, you think people are looking at you even if they don't know anything about you, you feel like you are incompetent in decision-making, and it affects you socially you start being grumpy, and neglecting your social responsibilities.' (P7)

Financial implications: Participants expressed fear of financial and job loss, as expressed below:

'It affects midwives emotionally, psychologically and also financially if you are suspended from work, for me it affected me a lot and I even started to leave the work and go and start something new, you end up having to change your social life, at home you become grumpy and then neglect children, sometimes you may get suspended without pay, and it gives financial stress. Financially is bad, you become angry with yourself, psychologically, you become depressed' (P7).

Conflict among colleagues: Regarding the writing of statements, a participant stated that: 'There becomes conflict between us as colleagues when we write statements, and the problem is to modify the statement to suit everybody because somebody want to know what you write and again you don't want to put somebody in the hot soup, so writing of statements is wrong sometimes you write lies trying to cover the colleague. I think the statement should be fair and confidential or rather written before your union representative.' (P8)

Factors contributing to malpractice: Several factors were cited by participants as contributing to unethical behaviour and professional malpractice. One of these was a lack of material and human resources. A shortage of resources with specific reference to a cardiotocograph machine (CTG) was a concern: 'Having one cardiotocograph machine causes delay on other patients and using fetoscope alone you won't be able to pick up complications, it may give wrong readings and it won't tell if there is bradycardia.' (P1)

'We did not have CTG before with the fetoscope, it was difficult to detect the fetal heart especially with women who have a big abdomen.' (P2)

Shortage of staff was cited as a challenge, as workload increases: ' If we are short staffed, we focus on others and others end up delivering on their own.' (P1)

'I think another community health centre or MOU is needed to relieve the influx of patient, it will relieve the stress on us because we cater for patient from Limpopo Province and from referring clinics.' (P5)

Wallace[31] supports the above by recommending an effective staffing model supported by adequate resources aimed to improve workflow and positive patient outcomes.

A report released by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research1321 highlighted the fact that the shortage of midwives in SA impacts negatively on maternal health, leading to a high morbidity and mortality rate, as also supported by SANC.[331

Delayed referrals: Delayed referrals of high-risk women from other clinics was stated as a contributing factor that led to the advancement of complications: 'Delayed referrals by other clinics to the MOU.' (P4)

And:

'Late bookings by antenatal mothers also add to the problems because complications may be picked up late.' (P4)

Financial problems: Participants were dissatisfied with remuneration: 'We were not paid overtime for maybe 8 months so who will want to work for charity if not being paid that's why midwives are not happy, so let people be paid for overtime.' (P8)

Dissatisfaction with remuneration leads to job dissatisfaction, which negatively affects the compassion levels of midwives, as supported by a study by Ergin et al.[341 on the compassion levels of midwives working in the delivery room.

Patients' rights: Litigation increases as women become more knowledgeable about their right to healthcare:

'People are aware of their rights, they hear the media everywhere and know what is right or wrong.' (P1)

McHale and Tingle[6] support this notion by indicating that claims of clinical negligence in the UK continue to rise as members of the public are more informed of their rights to equitable and efficient healthcare services.

Ho[35] concurs with the above statement by highlighting that more educated clients have higher expectations of healthcare, compounded by a demand for quality care. The findings of the present study also support the literature, as expressed below: ' It is not that the litigations are becoming too high, it is because people know their rights, there is transparency as the rights are written everywhere at the clinics and if they are not satisfied, they complain.' (P8)

Midwives' attitude: Midwives' attitudes were also found to be a contributing factor to professional malpractice, as confessed below: 'Sometimes we give attitude if the patient is not co-operating during delivery and you are thinking of saving the two lives.' (P5).

Positive staff attitude is one of the six key priorities that the Minister of Health listed in the National Strategic Plan for Nurse Education, Training and Practice (2012 - 13 to 2016 - 17)[361 to improve quality care, as recognised below: 'Obviously for him to come up with the six key priorities and attitude being one of them it means there is a problem with our attitude and obviously the attitude impacted on the ethical conduct of midwives.' (P6)

Participants further displayed responsibility regarding attitude management, as also revealed in a study by Mathibe-Neke et al.[371 on perceptions of midwives regarding psychosocial care: 'We need to refine our emotions and to display a positive attitude, pray to God and ask the new mercy for the day.' (P5)

Khali[381 conducted a study on nurses' attitudes towards patients in SA, which revealed that owing to shortages of staff and other frustrations encountered, nurses tend to reward co-operative patients with ideal care, whereas patients who were considered difficult were either ignored or their healthcare interventions were delayed. Regarding behaviour that amounts to negligence on the part of the healthcare provider, as per the Acts and Omissions Regulation R387 of 1985, Khali and Karani[39] and AbuAlRub[40] argue that nurses' frustrations stem from inadequate support from managers, unfair blaming, eroded morale and general work dissatisfaction. However, they do not condone such behaviour, as it is unprofessional.[41,38] On a more positive note, Miya[42] argues that although blamed for negative attitude and laziness, nurses continue to be at the forefront of health service delivery, and strive to ensure that most babies are born safely.

Discussion

This study sought to identify what midwives regarded as ethical practice. The findings revealed that midwives understand the ethical code of conduct; however, owing to challenges such as shortages of staff, shortages of material resources, non-compliance of midwives with policies and guidelines, fear of decision-making and lack of management support, ethical conduct is compromised.

With these challenges, it is difficult to envisage how participants manage the adverse events they come across, especially when women do not comply with or adhere to midwives' proposals for care plans. Moreover, Yarbrough et al.[43] highlight the fact that once midwives perceive value conflicts, retention might be adversely affected, as the practice environment stimulates midwives to consider whether to stay in their jobs or not. Managerial support can be effective to mitigate this challenge. It is clear from the study findings that it is often difficult for midwives to implement the basic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice in their daily encounters with women, due to workload. Abuya et al.[44] support this notion by stating that the impact of stress on healthcare providers might exacerbate physical or verbal abuse of patients, and that it would be ideal for providers to consider their values and the attitudes exhibited while providing care. The conclusion of studies by Mayra et al.[45] and Ishola et al.[46] was that job satisfaction, experiences of traumatic births, workload, bullying and powerlessness, which also featured in the findings of this study, affect compassionate care by midwives negatively. Furthermore, patient-related attributes, for example social status, family support, culture, myths around childbirth and intimate partner violence may lead to less co-operation from a woman in labour.

Strategies to foster and enhance ethical and supportive work climates as well as job-related benefits are recommended by Hashish,[47] based on the findings of a correlational study on the relationship between ethical work climate and nurses' perception of organisational support, commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intent.

Furthermore, high value has to be placed on education of women regarding their responsibilities during pregnancy and childbirth, so as not only to dwell on their rights, and also to be able to make informed choices. Nevertheless, midwives need to guard against factors that might negatively impact or threaten the woman's dignity during the midwife-woman interaction, which can be perpetuated by among other things, verbal abuse, privacy and confidentiality issues, loss of autonomy, discrimination and ignorance of the woman's preferences. [48] Mistreatment of women by maternal healthcare providers in birthing units during labour and childbirth has been documented globally, as stated by Mayra et al.[45] and Ishola et al.[46

Gumbi, cited in a report by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research,[32] supports the arguments above, stating that in one of the biggest labour wards in KwaZulu-Natal Province, the midwives and doctors have managed to reduce serious adverse events through teamwork. She indicates that the midwives receive ongoing training through monthly meetings, providing a platform where discussions are held through information-sharing of various scenarios or challenges encountered in clinical practice. This process has ensured that midwives are up to date with the latest developments, policies and protocols.

Content analysis in a qualitative study by Smith and Godfrey[22] led to the emergence of the following themes as all crucial in enhancing ethical behaviour among midwives: personal characteristics; professional characteristics; knowledge base; patient centredness; advocacy; critical thinking; and patient care. Hallam et al.[49] describe the role of midwives as based on the five Cs (care, compassion, competence, communication, courage) in providing women-centred care that could fulfil ethical practice.

London and Baldwin-Ragaven[50] highlight the point that midwives as healthcare professionals have an ethical obligation to advocate for women, and should commit to maximising the wellbeing of those in their care. Managerial support is also crucial, as discussed by Numminen et al.,[51] who recommend that nursing managers should understand their responsibilities in ethical leadership. A workplace ethics committee is often fundamental in monitoring and addressing ethical challenges, as suggested by Welsch et al.[52] It has also been suggested that midwives should conduct and participate in ethics rounds to enhance their ability to handle ethical dilemmas.[53] This notion is supported by Oosthuizen et al.,[54] in a study on women's experiences of childbirth at all levels of the healthcare system. They conclude that management should apply respectful obstetric care measures that align with the support needed by midwives, to improve governance in maternity facilities in order to enhance positive childbirth experiences for women. A study by Butler et al.[55] identified 12 domains of competency for respectful maternity care: being free from harm and mistreatment; maintaining privacy and confidentiality; preserving women's dignity; prospective provision of information and seeking informed consent; ensuring continuous access to family and community support; enhancing the quality of the physical environment and resources; providing equitable maternity care; engaging with effective communication; respecting women's choices that strengthen their capabilities to give birth; availability of competent and motivated human resources; provision of efficient and effective care; and continuity of care.

Recommendations

Administration/management

The following are recommended: effective management of staff shortages, which may include a plan for relief staff; debriefing sessions to be arranged for all staff involved, and counselling support offered where necessary; regular staff development through in-service training on ethical matters; values clarification and attitude training sessions; developing and facilitating a workplace ethics committee to mediate ethical conflicts in the workplace; managers to reinforce a sound procurement system to ensure that resources are available and material resources are in good working order to enhance efficient intrapartum care.

Midwifery practice

What is needed is for midwives to display a positive attitude or a good response to women's needs; effective communication among staff members; for midwives to make sure that they give one another proper reports about patients and document all care given, to ensure that there is continuity of care; for midwives to conduct and participate in ethics rounds as a form of support in handling ethical dilemmas; for midwives to assist one another during decision-making and affirming of findings before carrying out interventions to minimise errors; the empowerment of women through education to make them aware of their rights and responsibilities, so that they can make informed choices.

Further research

Further research should investigate the impact of malpractice on midwives, and explore efforts to reduce unethical practices, as well as nurse managers' ethical leadership.

Limitations

The study population of advanced midwives, who are meant to be mentors to inexperienced midwives, demonstrated ethical incompetence, which highlights a gap that needs to be filled through regular in-service education on ethical practice, and a need to reflect on the curriculum content of midwifery training to establish the extent of the inclusion of ethics. The sample size, however, despite data saturation, poses a limitation for transferability to a wider population.

Conclusion

Our findings illustrate the difficult circumstances under which midwives operate. It is clear that it is often difficult for participants to implement the basic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice in their daily encounters with women. Nevertheless, midwives need to strive to commit to compassionate care by engaging each woman in their care, in order to ensure a positive childbirth experience, as a negative experience might have long-term undesirable effects on the childbearing woman.

Acknowledgements. The authors acknowledge the labour units and the midwives who participated in the study and shared their experiences.

Author contributions. JMM-N: supervised the study, assisted in data analysis and prepared the manuscript. MMM: obtained data and participated in data analysis.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Maphumulo M. Various departments of health sued for millions. City Press, 20 April 2011.

2. Child K. Hospital horrors costing SA plenty. Sunday Times, 17 January 2014. https://www.timesmve.co.za/news/2014-01-17-hospital-horrors-costing-sa-plenty (accessed 21 April 2022).

3. Hood L, Fenwick J, Butt J. A story of scrutiny and fear: Australian midwives' experiences of an external review of obstetric services, being involved with litigation and the impact on clinical practice. Midwifery 2010;26(3):268-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.07.008 [ Links ]

4. Sturm BA, Dellert J. Exploring nurses' personal dignity, global self-esteem and work satisfaction. Nurs Ethics 2016;23(4):384-400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014567024 [ Links ]

5. Nyathi M, Jooste K. Working conditions that contribute to absenteeism among nurses in a provincial hospital in Limpopo Province. Curationis 2008;31(1):28-37. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v31i1.903 [ Links ]

6. McHale J, Tingle J. Law and Nursing. St Louis: Elsevier, 2007. [ Links ]

7. Arries E. Practice standards for quality clinical decision-making in nursing. Curationis 2006;29(1):62-72. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v29i1.1052 [ Links ]

8. Kulju K, Stolt M, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Ethical competence: A concept analysis. Nurs Ethics 2016;23(4):401-412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014567025 [ Links ]

9. Ito C, Natsume M. Ethical dilemmas facing nurses in Japan: A pilot study. Nurs Ethics 2015;23(4):432-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330/5574923 [ Links ]

10. Kinnane JH. Everyday encounters of everyday midwives: Tribulations and triumph for ethical practitioners. Aust J Midwives 2008. Carseldine: PhD thesis, University of Queensland, 2008. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16700 (accessed 8 July 2014). [ Links ]

11. International Council of Nurses. The ICN Code of Ethics for Nurses. Geneva: ICN,2012. [ Links ]

12. South African Nursing Council. The relationship between the scopes of practice, practice standards and competencies. Pretoria: SANC, no date. [ Links ]

13. Waghmare PR. Legal and ethical aspects of midwifery nursing: Descriptive approach to assess the knowledge of maternity nurses. Juni Khyat 2020;10(6):168-172. [ Links ]

14. Christensen LB, Johnson RB, Turner LA. Research Methods, Design and Analysis. 12th edition. Edinburgh: Pearson, 2015. [ Links ]

15. Burnard P, Morrison P, Gluyas H. Nursing Research in Action: Exploring, Understanding and Developing Skills. 3rd edition. New York: Macmillan Education, 2011. [ Links ]

16. Barbour R. Introducing qualitative research: A student guide to the craft of doing qualitative research. Los Angeles: Sage, 2014. [ Links ]

17. Polit DF, Beck CF. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence of Nursing Practice. 10th edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2017. [ Links ]

18. Burns N, Grove SK. The Practice of Nursing research. 8th edition. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2017. [ Links ]

19. South African Nursing Council. Competencies for midwives specialists. Pretoria: SANC, 2014. [ Links ]

20. Rich K, Butts JB. Foundations of Ethical Nursing Practice. Burlington: Jones & Barlett Learning, 2020. [ Links ]

21. South African Nursing Council. Code of ethics for nursing practioners in South Africa. Pretoria: SANC, 2013. [ Links ]

22. Smith KV, Godfrey NS. Being a good nurse and doing the right thing: A qualitative study. Nurs Ethics 2002;9(3):301-312. https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733002ne51209 [ Links ]

23. Griffith R. Accountability in midwifery practice: Answerable to mother and baby. Br J Midwifery 2012b;20(8):601-602. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2012.2007.525 [ Links ]

24. Erasmus K. To err is human, where does negligence malpractice and professional misconducts fit the puzzle. J Professional Nurs Today 2008;12(5):5-8. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC79242 (accessed 21 April 2022). [ Links ]

25. Klebanow D. The practice of malpractice. USA Today 24 March 2014.

26. Lewis P. Hard and difficult times - the provision of good midwifery care. Br J Midwifery 2012b;5:310-311. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2012.20.5.310 [ Links ]

27. South Africa. Children's Act No. 38 of 2005.

28. Griffith R. Midwives and confidentiality. Br J Midwifery 2008;16(1):51-53. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2008.16.1.27934 [ Links ]

29. McLeod-Sordjan R. Evaluating moral reasoning in nursing education. Nurs Ethics 2015;21(4):473-483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013505309 [ Links ]

30. Lachman VD. Applying the ethics of care to your nursing practice. Medsurg Nurs 2012;21(2):112-116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733010396818 [ Links ]

31. Wallace BC. Nurse staffing and patient safety:What's your perspective? Nurs Manag 2013;44(6):49-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000430406.50335.51 [ Links ]

32. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Responding to the needs of decision makers. Annual Report, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [ Links ]

33. South African Nursing Council. SANC registration and enrollment figures. Pretoria: SANC, 2014. [ Links ]

34. Ergin A, Ozcan M, Aksoy SD.The compassion levels of midwives working in the delivery room. Nurs Ethics 2020;27(3):887-897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019874495journals.sagepub.com/home/nej [ Links ]

35. Ho LF. Medico legal aspects of obstetrics: The role of the midwife in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Gynecol Obstet Midwifery 2009a;9:58-62. hkjgom.org/sites/default/files/pdf/v-09-p58-UA907.pdf (accessed 21 April 2022). [ Links ]

36. Department of Health, South Africa. The National Strategic Plan for Nurse Education, Training and Practice 2012/13 - 2016/17. Pretoria: Government Printers, 2011. [ Links ]

37. Mathibe-Neke JM, Rothberg A, Langley G. The perception of midwives regarding psychosocial risk assessment during antenatal care. Heal SA Gesondheid 2014;19(1):742-750. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v19i1.742 [ Links ]

38. Khali DD. Nurses' attitude towards 'difficult' and 'good' patients in eight public hospitals. Int J Nurs Pract 2009;15(5):437-443. [ Links ]

39. Khali DD, Karani AK. Are nurses victims of violence or perpetrators of violence? Kenyan Nurs J 2005;33(2):4-9. [ Links ]

40. AbuAlRub R. Job stress, job perfomance and social support among hospital nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36:73-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04016.x [ Links ]

41. Whyte A. Reputation on the line: Alison Whyte tracks the recent history of care failings that have put nurses' image in the spotlight. Nurs Stand 2011;26(12):18-21. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.26.12.18.s27 [ Links ]

42. Miya RM. Reflections: A life shared for the sick and knowledge dispensation. Nurs Updat 2015;40(1):30-31. [ Links ]

43. Yarbrough S, Martin P, Alfred D. Professional values, job satisfaction, career development, and intent to stay. Nurs Ethics 2017;24(6):675-685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733015623098 [ Links ]

44. Abuya T, Ndwiga C, Ritter J, et al. The effect of a multi-component intervention on disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15(224):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0645-6 [ Links ]

45. Mayra K, Matthews Z, Padmadas SS. Why do some health care providers disrespect and abuse women during childbirth in India? Women Birth 2020:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2021.02.003

46. Ishola, F, Owolabi O, Fillipi V. Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in Nigeria: A systematic review. PLOS One 2017;12(3):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174084 [ Links ]

47. Hashish EAB. Relationship between ethical work climate and nurses' perception of organizational support, commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intent. Nurs Ethics 2017;24(2):151-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733015594667 [ Links ]

48. Papastavrou E, Efstathiou G, Andreou C. Nursing student's perception of patient dignity. Nurs Ethics 2016;23(1):92-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014557176 [ Links ]

49. Hallam JL, Howard CD, Locke A,Thomas M. Communicating choice: An exploration of mothers' experiences of birth. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2016;34(2):175-184. [ Links ]

50. London L, Baldwin-Ragaven L. Human rights and health: Challenges for training nurses in South Africa. Curationis 2008;31(1):5-18. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v31i1.898 [ Links ]

51. Numminen O, Leino-Kilpi H, Isoaho H, Meretoya R. Ethical climate and nurse competency. Nurs Ethics 2015;22(8):845-859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014557137 [ Links ]

52. Welsch Jensen LE, Small R, et al. Nurses' perceptions of ethical issues in an academic hospital setting. Sigma Theta Tau International Conference, 2014.

53. Silen M, Ramklint M, Hansson MG, Haglund K. Ethics rounds: An appreciated form of ethics support. Nurs Ethics 2016;23(2):92-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014560930 [ Links ]

54. Oosthuizen SJ, Berg A, Pattison RC, Grimbeek J. It does matter where you come from: Mothers' experiences of childbirth in midwife obstetric units, Tshwane, South Africa. Reproductive Health 2017;14(151):1-11. [ Links ]

55. Butler MM, Fullerton J, Aman C. Competencies for respectful maternity care: Identifying those most important to midwives worldwide. Birth 2020;47(4):346-356. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12481 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J M Mathibe-Neke

mathijm@unisa.ac.za

Accepted 9 March 2022