Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Human Rights Law Journal

On-line version ISSN 1996-2096

Print version ISSN 1609-073X

Afr. hum. rights law j. vol.14 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

FOCUS: LAW AND RELIGION IN AFRICA: COMPARATIVE PRACTICES, EXPERIENCES AND PROSPECTS

Theologising the mundane, politicising the divine: The crosscurrents of law, religion and politics in Nigeria

Is-haq Olanrewaju Oloyede*

National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN)/University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

SUMMARY

From the embers of several ethnic groups colonially conjoined and subsequently amalgamated for sheer administrative convenience, modern Nigeria has emerged with internal contradictions. Unlike what happens in other climes, where many years of living together promote social harmony and mutual co-existence, Nigeria appears to be perpetually a tinderbox. Nationhood is threatened and politics defined along religious lines and religion itself highly politicised. This article highlights the critical factors responsible for the complexity of the Nigerian situation. These include socio-economics, religion, law, politics and education, among others, the interplay of which defines contemporary Nigeria, where insecurity is a national menace. In addition to offering a holistic analysis of general Nigerian and Nigerian Islamic perspectives on a number of issues that account for the near absence of positive and negative peace in the country, the article emphasises the imperative of a peaceful world, based on principles of justice and fair play in the distribution of resources, the promulgation of law, religious practice, media reporting and social commentary.

1 Introduction: Nigeria, a diverse and religious country

On his seventieth visit to Nigeria on 22 November 2012,1 the then Archbishop-designate of Canterbury, Justin Welby, remarked that, no matter how conversant with or knowledgeable about the socio-religious situation in Nigeria one is, one cannot gain an accurate impression of the country without a caveat: The issues are not as straight-forward or simple as they appear. Welby's informed impression or submission is predicated on the fact that there are other underlying factors. This observation aptly underscores the complexity of the Nigerian situation.

This article is intended to highlight a number of silent and salient factors behind the socio-economic problems in Nigeria, particularly as they relate to law, religion and politics, the cross-currents of which define her contemporary socio-political experience. Any analysis of inter-religious conflicts, political instability and apparent constant and unnecessary conflict of law in Nigeria is superficial unless the underlying factors are objectively studied and addressed. These factors include:

(a) the socio-ethnic and religious configuration of Nigeria;

(b) the nature of the federal in Nigeria;

(c) the effect of the religio-legal political compromise of 1960 and its abrogation on Northern Nigeria;

(d) the religious influence on public policy in Nigeria;

(e) whether Nigeria considers itself a secular or multi-religious nation;

(f) the abuse of education and educational institutions for the promotion of religious oppression, bigotry and hate in Nigeria;

(g) the socio-economic status of religion and religious leaders, especially independent clerics, in Nigeria;

(h) the relationship between religious politics and violence in Nigeria; and

(i) the entanglement of law and religion in Nigeria.

Nigeria, the most populous African country, is composed of a diverse ethnic and cultural mix of approximately 160 million people with some 250 ethnic groups and about 500 languages. The ethnic configuration of the country includes Yoruba (21 per cent); Hausa (21 per cent); Igbo (18 per cent); Fulani (11 per cent); Ibiobio (5,6 per cent); Kanuri (4 per cent); Edo (3 per cent); Tiv (2 per cent); Bura (2 per cent); Nupe (1 per cent); and others (9 per cent). The major languages are Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo with English, the colonial heritage, serving as the official language, and lingua franca. Adegbija, in his 'tentative' register of some 499 languages spoken in Nigeria, identifies the 'major' languages as including Annang, Badakare, Baruba, Bekawara, Berom, Bokyi, Bolewa, Buduna, Chamba, Ebira, Fulfude, Gwari, Ibiobio, Idoma, Igala, Ijo, Ikwere, Itsekiri, Jarawa, Jukun, Kaje, Kalabari, Kana, Kanuri, Kilba, Kutep, Margi, Mumuye, Nupe, Shuowa Arabic, Tangale, Tere, Tiv and Urhobo.2

Nigeria is also regarded as a highly-religious country. A BBC report some years ago find Nigerians to be the most religious people in the world.3 An October 2009 report of the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life confirmed earlier surveys that Muslims make up about 50 per cent of the population in Nigeria, with Christians making up another 40 per cent, and African traditional religionists constituting 10 per cent.4 The American cable television network CNN, in a published report, found that Nigeria is the sixth largest Muslim country in the world.5 This religious canopy embraces many social and ethnic groups.

2 Socio-ethnic and religious configuration of Nigeria

In the past, Nigeria was believed to be made up of the Hausas in the north, the Igbos in the east and the Yorubas in the west, although further studies have rendered the classification a fallacy and an over-simplification. The north and east have paid dearly for this popular but incorrect assumption. The large number of minority ethnic groups in the north have relentlessly challenged their domination by the Hausas, while diverse ethnic groups in the east and part of the west ensured the creation of the mid-west region shortly after the dawn of independence. It can also, arguably, be said that one of the underlying motivations for the birth of the defunct Republic of Biafra was the control of the minority groups in what was then known as Eastern Nigeria.

Before the advent of the British, there were hundreds of distinct ethnic and linguistic groups in the vast area now known as Nigeria. Each group, particularly in the south, had its own unique culture and system of governance. The Northern part of what is now referred to as Nigeria was more politically and administratively centralised than the independent kingdoms and autonomous communities in the south. The definition of either north or south is also contentious since some northerners, such as the Yorubas of the north, only grudgingly accept being tagged northerners.

The north, though made up of many ethnic groups, has Hausa as its lingua franca, since almost all the groups (with the exception of the Yorubas) have adopted it as the official medium of communication. The north was also unified and administered by an Islamic movement led by Usmanu Dan Fodiyo in 1804. The official religion in the north was indisputably Islam, though other religions were allowed and tolerated. Arabic was said to be the official language, but this was also a fallacy. The official language was Hausa, though the leadership of the movement was Fulani, a Fulfude-speaking ethnic group. Arabic script was used to transcribe the Hausa language. For example, up until the early part of this century, any Nigerian currency had a Hausa transcription of its value, but was written in Arabic script. The deletion of this feature from the currency during the civilian regime of President Olusegun Obasanjo (1999-2007), based on the incorrect premise that it was Arabic or Islamic, is an instance of theologising the mundane.

In its political structure, the north was essentially feudalistic. The east was essentially republican with autonomous communities, while the west was also feudalistic but with some modern refinement due to the influence of Western civilisation. The British colonialists adopted direct rule in Lagos and the southern protectorate, while the Northern protectorate had indirect rule through the established kings (emirs) who wielded both religious and political power, in what was essential Islamic rule. The rulers in South Western Nigeria also held both political and religious power. The religious power of the southern kings, however, concerned traditional religious rites which did not in the main cover either Islam or Christianity. With political authorities exerting control on religions, the politicisation of the divine became a natural corollary. Christians and adherents of African traditional religion in the north were essentially regarded as second-class citizens, much as Muslims were regarded in the south. The British encouraged the Christianisation of the south while being cautious in the dissemination of Christianity in the north. The protests of the Muslims in the south were largely ignored.6

The Nigerian law, it is worth noting, has three major sources. They are Euro-Christian British law, referred to as common law, Islamic law and customary law.7 The law traditionally applicable in Nigeria was customary law. In the north, before the advent of British rule, the applicable law in most of Northern Nigeria was Islamic law, which was regarded as customary law.8 The British introduced common law, with some modifications, to accommodate prevalent Islamic law in the north. In the south, the British common law, with a large dose of Christian ethics and practice, was made to co-exist with or even subvert customary law. With the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern protectorates of Nigeria in 1914, the British classified Islamic law as the customary law of Northern Nigeria. The implication of that was not immediately obvious to the peoples of Northern Nigeria. The subsequent invocation of the repugnancy doctrine to nullify some Islamic court judgments attracted some protests from the north.9

Muslims in the south, especially in the south west where they are in the majority, looked to Northern Muslims for religious relief, which was not as forthcoming as expected. This explains, to a large extent, the uneasy relationship between the two Muslim groups in Nigeria up to the present day.

3 Nature of the federal system in Nigeria

In many federal systems around the world, the constituent units are blocks which come together to submit their overall sovereignty to a central authority, while retaining control over certain specific features of government. In the case of Nigeria, the constituent units are not only the creation of the central authority, but each is also as internally heterogeneous as the overall federation. The composition of many of the constituent units is not based on any historical, cultural or linguistic affinity. They are merely a proclamation of the central authorities. Consequently, the agitation for more states is still as intense as ever.

The north, generally speaking, had been under a central Islamic government in the early part of the nineteenth century. The British created what is known as Southern Nigeria from a large number of diverse ethnic groups. The British then split the southern areas into the western and eastern regions, based only on geographical proximity. Consequently, at independence, Nigeria had three constituent units - North, West and East. In 1964, the mid-west was carved out of the west and some parts of the east. In 1967, the federal military government decreed 12 states out of these regions. The number rose to 19 in 1976; 21 in 1987; 30 in 1997; and 36 in 1995. The military therefore balkanised Nigeria into 36 states, at the whims and caprices of the ruling junta who, at times, sponsored civilian agitators to demand was originally intended. The 36 states are today regarded as the constituents of the 'federation', which is more unitary than federal. The military later informally introduced a supra-state structure called 'the Six Geo-Political Zones', which again have neither the mandate of the citizens, nor internal coherence or cultural identity. Table 1 shows some of the demographic features of the six zones.

This informal geopolitical structure, which seems to enjoy some acceptance, has raised other challenges of fact and perception. For instance, any zone with five states requires an additional state in the zone to preserve the equality of zones. The result has been intra-regional politics based on historical past of 'North', 'West' and 'East'.

The geographical analysis is just a superficial externality; the real blocks or constituent unites can be said to be five: (a) the Hausa/ Fulani majority in the north who are almost totally Muslim; (b) other minority ethnic groups of the north who are non-Muslim; (c) the Igbos (Christian); (d) minority ethnic groups in South-Eastern and Mid-Western Nigeria (predominantly Christian); and (e) the west (mixed in religion). The religious and political voices of these five shape the nature of the law and socio-economic status of the country. The situation is complex and dynamic, because it more often than not involves a shift of identities depending on circumstances and convenience. Religious, ethnic or regional identities are being manipulated for political and personal ends.

4 Religio-legal political compromise of 1960 and its aftermath in Northern Nigeria

Immediately before independence, one of the three major contentious issues between the north and the south was the issue of applicable criminal law. Islamic law, both civil and criminal, was the applicable law in most parts of Northern Nigeria prior to independence in 1960. Up until 1956 it was called 'native law and custom'. Anderson rightly observed that Islamic law 'was still up to 1960 more widely, and in some respects more rigidly, applied in Northern Nigeria than anywhere else outside Arabia'.11 In the southern parts of Nigeria, the Nigerian criminal code was the applicable law in criminal matters, while Christian marriages and family law were incorporated into the statutory marriage law which operated in Southern Nigeria along with customary law.

As independence approached, there was a need for a uniform criminal law and the Nigerian criminal code applicable in Southern Nigeria was to be fully adopted for the north and the south. The Islamic scholars and jurists (ulama), as well as the greater part of Muslims in Northern Nigeria, objected to the abrogation of Islamic criminal law in Northern Nigeria. This prompted the Northern government to set up a panel of six members to recommend an appropriate legal system for Northern Nigeria in 1958. The panelists included (i) the Chairperson of the Pakistan Law Commission; (ii) the Chief Justice of Sudan; (iii) Professor JND Anderson, a scholar of comparative law and religion at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London; (iv) two Islamic scholars; and (v) Chief Peter Achimugu, Christian northerner and minister in the Northern regional government.12

The Committee submitted a report which was the basis of the famous '1960 Compromise', whereby penal and criminal procedure codes were enacted for Northern Nigeria. The penal code was a replica of the Sudan Penal Code which incorporated diluted versions of Islamic criminal law.13 At that time, Islamic law, or Shari'a, was confined to the law of personal status, which incorporated family and civil cases in which all parties were Muslims. Corporate and commercial litigation was to be dealt with under statutory law, customary law or the law under which the parties concluded their contract. The Shari'a Court of Appeal was established for Islamic law civil cases, while the Native Courts Appellate Division was created in the State High Court for customary law cases. A panel of High Court judges and a judge (kadi) of the Shari'a Court of Appeal sat to resolve cases involving a conflict of law between customary and Islamic law cases.14 A Yoruba northerner who was from the opposition party in the north, Chief Josiah Sunday Olawoyin, unsuccessfully opposed the arrangement in the regional parliament on the premise that it was to 'Islamise the whole of the Northern Region'.

The northerners were persuaded to accept the code on the basis that it was necessary for independence and foreign international trade and commerce.15 The compromise was reviewed in 1962 by a panel of three Christians and three Muslims, who approved its implementation. Williams applauded the arrangement in which 'the [penal] code which in spite of, or perhaps even because of its not being an exact copy of English criminal procedure, is looked upon as their own by Northern Nigerians and which on the whole is administered with some pride and with increasing impartiality and efficiency'.16 The criminal code of Southern Nigeria governs criminal matters in Southern Nigeria.

Thus, right from independence, it was clear that religion, law and politics, alongside ethnicity, were the bedrock of the federation. It is surprising, therefore, that the Shari'a imbroglio at the inception of civilian rule in 1978 was largely treated as a strange development. The main bone of contention was that, since each of the states in Northern Nigeria had a Shari'a Court of Appeal, Muslims called for a Federal Shari'a Appeal Court to adjudicate on all Shari'a cases where the parties were Muslim. This was rejected by the majority of the delegates in the Constituent Assembly. Apart from the religious sensitivity which the voting pattern aroused in the electorate, the ensuing debate created very hard feelings on both sides which would take a long time to erase. The debate and its fallout have been well-documented.17

The compromise was that the composition of the (Federal) Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court would include some experts in Shari'a to decide all Islamic law family matters on appeal. It is also significant that one of the pillars of compromise of 1960 and 1979, which was that a kadi of the Shari'a Court would sit on a panel of the judges of the High Court when issues of conflict of Shari'a and customary laws were being decided, was later judicially nullified by the common law justices at the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court on the basis that such kadis were not qualified common law lawyers.18 The greater part of Muslims in Nigeria perceive the judicial nullification of the political agreement as a product of professional rivalry between Muslim justices (who are qualified common law barristers) and the kadis (who were experts in Islamic law but were not called to the Nigerian Bar as advocates). This is another dimension of the crisis that caused a large number of Muslims to develop hard feelings against the common law system. The 1979 Constitution operated for four years (1979 to 1983) before the military intervention, which lasted 16 years. On the eve of the third civilian dispensation in 1999, the controversy was not allowed to degenerate as it did during the Second Republic. The 1979 compromise was incorporated into the 1999 Constitution.

Immediately after the inception of civilian rule, agitation for the nullification of the compromise of 1960 began in the north. The bases of the agitation were said to be the following:

(a) The compromise of abandoning the Islamic penal system at the eve of independence was not a necessary prerequisite for independence as they were made to believe.

(b) The venom poured on Muslims during the 1979 Shari'a debate and the Christian opposition to Nigerian membership of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) (OIC), to which many countries with a Muslim minority belong.

(c) The judicial nullification of an aspect of the 1960 compromise whereby a kadi would be a member of the panel of a19state High Court on issues involving Islamic law in Northern Nigeria.19

(d) The application of Islamic law and its penal system in other independent nations of the world and the influence of global Islamic revivalism.

(e) Restriction of Islamic family law to Northern Nigeria where Christian/ statutory family marriages are also provided for through the state High Courts, but without making Islamic family courts available to Muslims in the southern part of Nigeria.20

(f) The mischievous application of the repugnancy doctrine which the Islamic law scholar SK Rashid has blamed for the crises in Nigeria, observing that '[i]n Nigeria, the abrogation of Islamic criminal law and mischief of repu2g1nancy clause have played havoc with the law and other situations'.21

5 Abrogation of the 1960 compromise in 12 states in Northern Nigeria

The aforementioned circumstances in 1999 prompted the Zamfara state parliament to enact a law,22 which restored the pre-1960 penal system in that state. The turnout of Muslims at the 27 October 1999 launching of the restoration of Islamic penal law for Muslims was summed up in a news report as follows:23

[It was] what could better be described as 'mother of all launchings'. Gusau, the capital of Zamfara state, in the history of its existence witnessed for the first time a crowd that cannot easily be compared to any recent gathering in Nigeria ... Three days to the D-day, people started coming into Gusau. In fact, about two million Muslim faithfuls from all parts of the country converged in the state capital to herald the commencement of Shari'a in the state. Every available space within the capital city was converted by traders for their wares . The Gusau-Sokoto, Gusau-Zaria [and] Gusau-Kano roads had the busiest traffic ever as people came from these directions in thousands. Those who could not afford transport trekked from appreciably far distances to witness the occasion . Movement in the town was brought to a standstill as the crowd covered a radius of four kilometers.

The event was slated for 8:00 am at the Ali Akilu Square but, interestingly enough, the square came to full capacity on the eve of the launching. Around 10:30 am the governor, Ahmad Sani, made a triumphant entry into the square amidst a thunderous ovation of welcome. At the appearance of the governor, the shouts of Allahu Akbar (God is great!) filled the air while the governor managed to squeeze his way to the high table where other dignitaries ... were seated.

The programme ... showed that the events would only take three to four hours but many items on the agenda were skipped when it became apparent that the occasion may start recording casualties ... Scores of the people fainted because of exhaustion and suffocation. The good, however, was that the members of the Islamic Aid Groups were ... at hand to carry shoulder high any casualty, not without difficulty anyway, as they pass the victims across the wall of the square for those outside to receive them and take to the hospital ...

[Among the speakers] was the Aare Musulimi of Yorubaland, Alhaji Abdulazeez Arisekola Alao, [who] said he was the happiest man on earth having been alive to witness the historic occasion. [He] thanked the governor and the members of the state House of Assembly who, according to him, unanimously passed the Bill on Shari'a into law, thereby making it possible 'for Allah's law to be operative in Zamfara State instead of manmade law forced on us by our colonial masters'.

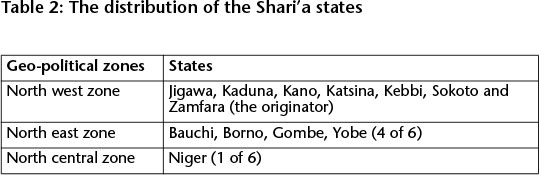

This popularity must have enticed 11 other governors in the northern states, where Muslims are in the majority, to follow suit. The motivation was more political relevance and advantage than religious commitment on the part of most of the governors. By the end of 2000, 12 states had enacted one form or the other of the Shari'a codes (penal system). Those states are presented in Table 2.

The popular but erroneous interpretation of the Shari'a revival was that it was a northern reaction to the emergence of a Christian president. The two major contenders for the presidency were Christians. The majority of the votes from the south-west zone, where the two leading contenders came from, were not votes for President Obasanjo, who won by attracting massive votes from the Northern and Muslim-dominated states. In addition, the principal sponsors and supporters of his candidacy were Northern Muslims. The table below contains the results of the presidential elections in Nigeria since 1979. The results of the topmost contenders (with not less than 10 per cent of votes) are shown with their religious affiliation and zones of origin.

The table shows clearly that Muslims could not have been opposed to the emergence of President Obasanjo in 1999. The two contenders were Christians from the south west. It was rather a move to appease the south west, which was the home of the winner of the 1993 annulled election. It is also instructive that the former military president who annulled the election results was a major promoter of President Obasanjo's candidacy - probably as a strategy to pave the way for his own anticipated later return as a democratically-elected President. It is similarly revealing that, while the two contenders in 1999 were Christians of south west origin, the two leading contenders in 2007 were Muslims of North-West origin. The two contenders in 1993 were Muslims. It is clear that the shift of identities and affiliations has been a ploy by the elite to utilise whichever religion, ethnicity or other primordial factors to maximise political advantage. It is also difficult to absolutely implicate one factor for the result.

The names of political parties before and immediately after independence also buttress the ethnic and geopolitical inclinations of the political parties. Parties such as Igala Union, Igbira Tribal Union, Mabolaje Grand Alliance, Kano Peoples Party, Zamfara Commoners Party, and so forth, did not hide ethnic identities while regional identities were displayed by the names of parties such as United Middle Belt Congress, Northern Peoples' Congress, Niger Delta Congress, Northern Elements Progressive Union, and so forth. The policy of not reflecting ethnicity in the names of registered political parties succeeded only in consigning it to the underground, but did not reduce the potency of ethnic factors in national politics. It is thus clear that the constituent units of Nigeria are only figuratively its regions, zones and states - the real de facto operational constituents, which are not formally acknowledged, are the political parties organised along ethnic lines.

6 Religious influence on public policy in Nigeria

Some light has been shed thus far on how religion plays an underlying role in public policy in Nigeria. The influence of the inherited British system, with its emphasis on the separation of state from religion, had a negative impact on the public administration of the country. The United Kingdom cannot be said to be a secular country, due to the Christian origin of many of its customs and practices. Its law can be said to be 'common law' in Britain, but not for a nation as diverse as Nigeria.

For example, the statutory Marriage Act bequeathed to Nigeria is based on the Christian principle of monogamy. Many privileges granted to couples under the law are denied to those who marry under Islamic or customary law. Area courts (customary and Islamic) in Northern Nigeria are excluded from cases 'arising from or connected with a Christian marriage',25 so also are customary courts in Southern Nigeria barred from hearing cases 'related to Christian marriages'.26 Christian marriages are statutory marriages for which the High Court is the court of first instance. The legal scholar LB Curzon has correctly observed:27

The influence of the canon law was important, in that some of the fundamental common law principles were derived from ecclesiastical doctrine. Our laws of marriage grew from the body of the canon law.

In Harrey v Farine, Justice Robert Lush concluded:28

Our (UK) laws do not recognise a marriage solemnised in that (Islamic) country, a union, falsely called marriage, as a marriage to be recognised in our Christian country.

Further, in Bownman v Secular Society Ltd29 it was decided that30

[t]he UK is and has been a Christian state. The English family is built on Christian ideas; and if the national religion is n ot Christian, there is none, as English law may well be called a Christian law.

The Christian Association of Nigeria recently publicised its involvement in the religious manipulation of foreign policy of some supposedly secular Euro-American countries through closed-door sessions with foreign embassies, at the end of which the Association described Christians who acknowledged that religious fanaticism in Nigeria cuts across religious divides as 'useful idiots'.31 On the other hand, an official land allocation paper from a state ministry contains a caveat that the land 'cannot be used for brothel or church'.32

7 Nigeria: A secular or multi-religious nation?

A number of studies have addressed the secular and religious nature of Nigeria.33 It is generally believed that the observance of the weekly Sabbath on Sunday is non-religious, whereas at least in origin it was based on biblical customs.34 In Dickson v Marcus Ubani,35 the Seventh Day Adventist Church sought to enforce the right of its members to a Saturday Sabbath. The Church pursued the right until Saturday was granted as public holiday during the reign of a Christian military ruler General Yakubu Gowon (1967-1975). In Southern Nigeria, spectators and litigants are obliged to take off their caps (as if they were in church), whereas this Christian church practice is not extended to the courts in the United Kingdom.

Until 1982, when Muslim judges refused to participate in church services in the south-west part of Nigeria, the annual opening of court sessions were held in churches alone with all judges in attendance, irrespective of religion. It was only in 1982 that Muslim judges decided to go to mosques while the Christians went to churches. In the north, such sessions are held in the courts.

The heavy expenditure of public funds on pilgrimages, such as the Hajj and the Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem and annual Christmas carols, betrays the secularity theory. Muslims and Christians exhibit their faith in the public arena in such a manner that suggests that religious allegiance is paramount. The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria avoids the word 'secular' and instead states that 'the government of the Federation or of a state shall not adopt any religion as state religion'.36 What the nation does is to support all religious groups and activities in varying degrees, depending on who is in the majority or in power. The reality is that Nigeria is a multi-religious and not a secular state.

8 Abuse of education and educational institutions in Nigeria for the promotion of religious oppression

Secularism is 'the belief that the state morals, education, etc should be independent of religion'.37 It can be further explained as a 'system of beliefs which rejects all forms of religious faith and worship, the view that public education and other civil policy should be conducted without the introduction of a religious element'.38 Western education in Nigeria has been a tool for the propagation of Christianity and the denigration of Muslims and Islam. In addition to the historical fact that the negative attitude of Nigerian Muslims (particularly in the north) was based on fear and the experience of being lured out of Islam, public educational institutions continue to be used to wage psychological and social wars against Muslims. Three examples will suffice.

The first example concerns the University of Ibadan, a public university in Nigeria. In April 2000, a Christian lecturer in a course on land law asked his Christian and Muslim students to answer questions based on a fictional land law.39 The parties in these hypothetical problems bore the names of 'Alhaji Looter' and 'Muhammed Kill-n-Go'. The first character defaulted on mortgage loans. The second was a fundamentalist proponent of Shari'a who attempted to convert his landlord's family to Islam before seducing the landlord's wife and arranging for hoodlums to pull down the family's ancestral shrines, in addition to refusing to pay rent (ishakole) to the landlord's family for three years. In both cases, the use of derogatory names for Muslim characters, who were further defined by their unscrupulous actions, could not have been well received by the Muslim students in the course.

In a second example, two students, Owo Eje40 and Iyawo Alarede,41 were prescribed textbooks for secondary school public examinations in Nigeria. The books contained obscene caricatures of Muslims and Islam. In light of the recent protests at the time from Muslims of the south west, the textbooks had to be reviewed to delete their extremely offensive anti-Islamic expressions and fictions.

A third example was contained in the pages of a textbook on English prescribed for pupils of public primary schools in Nigeria and procured and distributed free by the Federal Government of Nigeria.42 The book was published by the reputable Macmillan Publishers of Ibadan but printed in Malaysia. The text describes a legendary war chief Gandoki of Northern Nigeria who recounts stories to young boys of fighting in the Muslim army of Shehu Dan Fodio in the battles to convert the Fulani 'unbelievers'. Gandoki recounts his warning to the Fulani: 'If you follow Islam, I'll let you go free; if you don't follow Islam, I'll cut off your heads.' Gandoki describes further adventures in the land of the jinn in which he builds a school for children. As he recounts:

Every morning and every evening, I taught them the words of the Prophet. The chief of the jinn took me from place to place and as I travelled I taught the people about Islam. I killed those who would not pray to God.

These examples and many others have compromised the capacity of education to reverse the unfortunate trend of religious bigotry. Instead, educational institutions, including public ones, continue to serve as veritable breeding grounds for hate and religious intolerance. Where then lies the salvation?

9 Socio-economic status of religion and religious leaders in Nigeria

Most Nigerians subscribe to either Christianity or Islam.43 For various cultural and psychological reasons, Nigerians regard religion as a shield or shelter against perceived enemies.44 Consequently, religious leaders wield a considerably high influence over their flock. Many Nigerians would not embark on any venture without spiritual sanction from their religious leaders, who take maximum selfish advantage of such consultations. They are also considered to possess supernatural powers to make miracles and wonders occur.45 More often than not, such miracles are contrived. Ceremonies and festivities are common in society and none takes place without the involvement, in one way or the other, of the religious leaders who make many of them very wealthy. Spiritual healing powers are also claimed by or ascribed to many religious leaders.46

The situation provides a fertile ground for independent clerics who look for excuses to establish personalised religious movements to which followers faithfully contribute a prescribed portion of their income. A tithe of one tenth of the gross income of a Christian and one fortieth of the net income of a Muslim, after meeting all expenses, is a sacred prescription. A large proportion, if not all in some cases, ends up in the personal purse of the religious leaders. Religious leadership has become hereditary rather than being based on merit. In these circumstances, all commercial tricks are employed for maximum benefit under the cloak of religion. False and exaggerated alarms of religious persecution are at times raised to attract sympathy and financial support of undiscerning foreign sympathisers. A number of religious leaders have been found to be illegally receiving regular subventions from the funds of the public and public-quoted companies.47 It would, therefore, be understandable why religious leaders may strive to, through fair and foul means, install their own disciples in strategic public and corporate positions.

10 Religious politics and violence in Nigeria

The current Boko Haram scourge in the north of Nigeria, as well as the kidnapping and massive theft of crude oil in the south, is traceable to soured political maneuvers and socio-economic environment. It is generally believed that groups established for the promotion of political ends fell out with their political principals, who were then accused of abandoning their human tools after attaining their desired political goals. Powerful politicians responded to the challenges with brutal force which further aggravated the crises. With access to arms and ammunition initially procured by political thuggery, the deprived members of society turned to ethnic and religious camouflage as a platform for raising arms against society. If Boko Haram is a purely Islamic movement against non-Muslims, why are the majority of the victims Muslims? It seems more likely the case that interreligious acrimony was created to attract the maximum effect of creating anarchy and turmoil in the country. Rather than creating synergy to identify and uproot criminality and terrorism, energy is being dissipated on interreligious controversies.

It must nevertheless be acknowledged that indoctrination and outright ignorance have misled some individuals into religious extremism and violence. Such individuals are found in virtually all major religions. The Boko Haram phenomenon originated in the extremist perceptions of a few individuals in Nigeria. It is similar to the use of Christianity by Joseph Kony over the past two decades to wage a devastating war on the people of Northern Uganda. Such perversion of religion may have led groups to use Islam as an alibi for violence, but other factors may be at play.

For instance, another dimension of the spate of bombings and other violence generally believed to be perpetuated by the faceless Muslim group is that a number of culprits apprehended were non-Muslims who were hiding under the chaotic situation to settle intra-religious scores within the Christian community. Furthermore, Henry Orkah, who was recently convicted and sentenced in South Africa for masterminding the 1 October 2010 bombing in Abuja, Nigeria, is a Christian. His brother, who recently complained in detention that he was being tortured to implicate some Muslim leaders in the bombing episode, is a Christian. There are a number of media reports of Christians found to be behind the bombing of their own churches.48

A renowned American professor of African history, Jean Herskovitz, recently gave a succinct statement of the origin of Boko Haram in the New York Times, arguing:49

Boko Haram began in 2002 as a peaceful splinter group. But it was not until 2009 that Boko Haram turned to violence, especially after its leader, a young Muslim cleric named Mohammed Yusuf, was killed while in police custody. Video footage of Mr Yusuf's interrogation soon went viral, but no one was tried and punished for the crime. Seeking revenge, Boko Haram targeted the police, the military and local politicians - all of them (the politicians) Muslims.

The dreaded group turned its inexcusable venom on innocents -Christians in particular - which is very un-Islamic. The state security agency recently confirmed that different criminal groups currently falsely claim to be Boko Haram. On this point, Herskovits further observes:50

Governments and newspapers around the world attributed the horrific Christmas Day bombings of churches in Nigeria to Boko Haram ... [which] has been blamed for virtually every outbreak of violence in Nigeria. But the news media and American policy makers are chasing an elusive and ill-defined threat; there is no proof that a well-organised, ideologically coherent terrorist group called Boko Haram exists today. Evidence suggests instead that, while the original core of the group remains active, criminal gangs have adopted the name Boko Haram to claim responsibility for attacks when it suits them . It was clear in 2009, as it is now, that the root cause of violence and anger in both the north and south of Nigeria is endemic poverty and hopelessness.

Meanwhile, Boko Haram has evolved into a franchise that includes criminal groups claiming its identity. Revealingly, Nigeria state security services issued a statement on November 30, 2011 identifying members of four 'criminal syndicates' that send threatening text messages in the name of Boko Haram. Southern Nigerians - not northern Muslims - ran three of these four syndicates . And last week, the security agents caught a Christian southerner wearing northern Muslim garb as he set fire to a church in the Niger Delta. In Nigeria religious terrorism is not always what it seems. None of these excuses Boko Haram's killing of innocents. But it does raise questions about a rush to judgment that obscure Nigeria's complex reality.

The Nigerian Catholic Bishop of Sokoto Diocese and outstanding scholar, Mathew H Kukah, recently spoke candidly in an 'Appeal to Nigerians' in which he observed of Boko Haram saga:51

On Christmas day, a bomb exploded at St Theresa's Catholic Church, Madalla, in Niger State, killing over 30 people and wounding a significant number of other innocent citizens who had come to worship their God as the first part of their Christmas celebrations. Barely two days later, we heard of the tragic and mindless killings within a community in Ebonyi State in which over 60 people lost their lives with properties worth millions of naira destroyed and hundreds of families displaced . The tragedy in Madalla was seen as a direct attack on Christians. When Boko Haram claimed responsibility, this line of argument seemed persuasive to those who believed that these merchants of death could be linked to the religion of Islam. Happily, prominent Muslims rose in unison to condemn this evil act and denounced both the perpetrators and their acts as being un-Islamic. All of this should cause us to pause and ponder about the nature of the force of evil that is in our midst and to appreciate the fact that contrary to popular thinking, we are not faced with a crisis or conflict between Christians and Muslims. Rather, like the friends of Job, we need to humbly appreciate the limits of our human understanding.

In the last few years, with the deepening crises in parts of Bauchi, Borno, Kaduna and Plateau states, thanks to the international and national media, it has become fanciful to argue that we have crises between Christians and Muslims. Sadly, the kneejerk reaction of some very uninformed religious leaders has lent credence to this false belief. To complicate matters, some of these religious leaders have continued to rally their members to defend themselves in a religious war. This has fed the propaganda of the notorious Boko Haram and hides the fact that this evil has crossed religious barriers. Let us take a few examples which, though still under investigation across the country, should call for restraint on our part.

Sometime last year, a Christian woman went to her own parish church in Bauchi and tried to set it ablaze. Again, recently, a man alleged to be a Christian, dressed as a Muslim, went to burn down a church in Bayelsa. In Plateau State, a man purported to be a Christian was arrested while trying to bomb a church. Armed men gunned down a group of Christians meeting in a church and now it turned out that those who have been arrested and are under interrogation are in fact not Muslims and that the story is more of an internal crisis. In Zamfara State, 19 Muslims were killed. After investigation it was discovered that those who killed them were not Christians. Other similar incidents have occurred across the country.

Indeed, there have been two reports of cases in which those who attempted to or successfully bombed churches were confirmed members of the church.52 This prompted the zonal Chairperson of CAN, quoting Matthew 24 on the 'destruction of the temple and signs before the end of time', to refer to the church bombings as 'this strange development as signs of the end of time'.

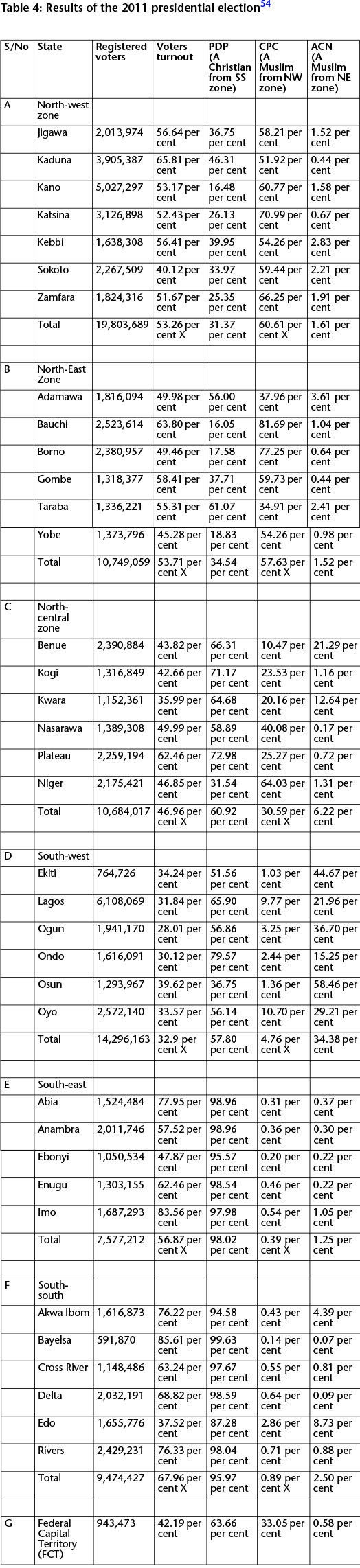

There were reports that a Muslim candidate for the 2011 presidential election openly asked Muslims to vote for him on the basis of religion, and the Christian Association of Nigeria, the umbrella body of Christians in Nigeria, publicly declared support for the Christian among the three topmost candidates. In 2000, the President of CAN, while reacting to the Shari'a revival in the north, publicly announced that 'whether they like it or not, we will not allow any Muslim to be President of Nigeria. I am declaring this as President of CAN'.53

This development was a very dangerous and destructive trend for the nation. That notwithstanding, the results of the election, when compared with previous presidential elections and against existing ethnic and political groupings, gave no room for the categorical isolation of religion as the main factor in the election. It is difficult to distinguish religion, ethnicity or politics as major factors in the results because the different configurations at times coalesce. In such cases, coincidence may be at play, as can be deduced from the table that follows:

For instance, at one point in 2011 there were equal numbers of Muslim and Christian governors in Nigeria, despite the fact that each state independently elected its governors. While four of the 19 governors in the Northern zones were until recently Christians, four of the 17 governors in the southern zones are Muslims. This again is another coincidence. Two of the Christian governors in the north were involved in separate air mishaps. These accidents have also thrown into relief the tragicomic nature of religious politics in Nigeria. As a result of these accidents, the Muslim deputies of the two governors had to take over, one temporarily and the other permanently. One of the remaining two Christian governors in the north recently informed a church congregation that the accidents, which reduced the number of Christian governors in the north, were the result of a spiritual onslaught against Christians.55 He worried that he might also be a victim, but he was reminded that his deputy and the third in command in his state are also Christians. He chose to gloss over the fact that a Muslim governor in the north was also in hospital as a result of a fatal road accident and two governors in the south were currently not in office as a result of ill-health. The deputies of the three ailing governors are Christians which belies the claim of an Islam-inspired spiritual war theory.

This is an example of how extraneous interpretations can be given to virtually any incident in the country. It matters a little to the 'smart' governor that the wives of three of the four Muslim governors in South-Western Nigeria are top Christian leaders, and that the wife of the northern Christian governor who is recuperating as a result of the plane crash is a Muslim and an Alhaja.

11 Conclusion: Religion, politics, and other causal factors

At the global level, Islam faces a number of challenges, some of which are unnecessary. The international media constantly stigmatises Islam. For example, the Norwegian Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 souls in a shooting spree, was protesting, among other grudges, the 'Islamification of Europe'. He was not called a Christian terrorist whereas, if he had been a Muslim, the international media would have labelled him an Islamic terrorist or fundamentalist. There are many such selective demonisations in the media. The Israel-Palestine conflict, which is perceived in Nigeria as a Christian-Muslim conflict, is far from that - there are Christians, Jews and Muslims across the divide. It was originally a conflict over land, but it has become a matter of religion.

Any person genuinely interested in world peace should be concerned about the increasing polarisation of the world in the quest for power and influence. It is paramount that the necessary steps be taken to avert hypocritical lip service to humanity when the reality is an unbridled urge for exclusion and a threat to world peace. The infamous claim of the presence of weapons of mass destruction that led to the invasion of Iraq was found to be a ruse, but it is one which has consumed a large number of human beings. It is therefore necessary to note that, while Nigeria is just a case study, a number of lessons can be learned from the Nigerian experience.

The situation in Nigeria has called attention to the impossibility of compartmentalisation of public administration into religious, political or social categories. It is also obvious that law, politics and religion have been intractably integrated in a manner that questions the classification of Nigerian conflicts and disputes along religious, political or legal lines. It is necessary to find ways to address those salient factors that obscure a causative and precise diagnosis.

* NIGERIABA (Hons), PhD (Ilorin); ioloyede@yahoo.co.uk

1 The incumbent Archbishop of Canterbury at Abuja in the company of Tony Blair on the occasion of the launching of the Tony Blair Faith Foundation. The author was present at the event. See 'Tony Blair, Bishop Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, and HRH Prince Ghazi of Jordan announce action for reconciliation in Nigeria' Tony Blair Faith Foundation Blog, 22 November 2012, http://www.tonyblairfaithfoundation.org (accessed 31 January 2014).

2 EA Adegbija Multilingualism: A Nigerian case study (2004). [ Links ]

3 'BBC votes Nigerians world most religious people' Daily Independent (Lagos) 27 February 2004 A1 6.

4 Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life Tolerance and tension: Islam and Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa (2010).

5 RA Greene 'Nearly 1 in 4 people worldwide is Muslim, report says' CNN 12 October 2009. See also Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life Mapping the global Muslim population (2009). For even more recent statistics, see also Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life The future of the global Muslim population (2011).

6 Lagos Weekly Record 28 July 1894; Political Memorandum, London, 1970 265; JND Anderson Islamic law in Africa [1954] (2008) 222-223.

7 AG Karibi-Whyte History and sources of Nigerian criminal law (1993) 58.

8 JM Abun-Nasr 'The recognition of Islamic law in Nigeria as customary law' in JM Abun-Nasr et al (eds) Law, society and national identity in Africa (1990).

9 IO Oloyede Repugnancy doctrine and the practice of Islamic law in Nigeria (1993).

10 National Population Commission of Nigeria, http://www.population.gov.ng/index.php/119-about-us/about-nigeria (accessed 30 April 2014). [ Links ]

11 Anderson (n 6 above) 219.

12 P Ostien (ed) Shari'a implementation in Northern Nigeria 1999-2006: A source book (2007) vol I, ch 2 14. [ Links ]

13 S Kumo 'Shari'a under colonialism-Northern Nigeria' in N Alkali et al (eds) Islam in Africa (1993) 8.

14 Ostien (n 12 above) vol I, ch 4, 51 & 54 (statement by the government of the Northern region of Nigeria on the re-organisation of the legal and judicial systems of the Northern region).

15 Ostien (n 12 above) vol I, ch 1, 5 & 6 (debates of the House of Assembly (Second Legislature) third session, 12 to 19 August 1959, Column 501).

16 Ostien (n 12 above) vol I, ch 1, 7 (quoting TH Williams 'The Criminal Procedure Code of Northern Nigeria: The first five years' (1966) 29 Modern Law Review 272).

17 IO Oloyede Shari'a versus secularism in Nigeria (1987).

18 Mallam Ado & Hajiya Rabi v Hajiye, Dije CFCA/K/69/82 on the basis of secs 242(i) and 2(a)-(e) of the 1979 Constitution. See also Umar v Bukar Sarki FCA(k) 1985.

19 See P Ostien 'An opportunity missed by Nigeria's Christians: The 1976-78 Shari'a debate revisited' in BF Soares (ed) Muslim-Christian encounters In Africa (2006) 238-243 (quoted in Ostien (n 12 above) vol I, ch 1, pp 7-8: 'Nigeria's Muslims ... in the resulting 1979 Constitution, lost every one of the perquisites that had made the settlement of 1960 palatable to them in the first place' and '[T]he new penal and criminal procedure codes, with other elements of the settlement of 1960, came to be seen as ill-motivated and unjustified in positions forced on an unwilling or deluded Sardauna (Premier of Northern Nigeria) by the undue influence of the British.'

20 Oloyede (n 17 above) 12. Eg, a Christian in any part of Nigeria can be legally wedded in a church and the marriage is considered done under the official statutory Marriage Act, with attendant privileges which include a judicial resolution through state High Courts, whereas any Muslim marriage outside Northern Nigeria is regarded as a mere customary marriage which (unlike its Christian counterpart) a High Court will not entertain. He or she would either be contended with the Customary Court (with no consideration for Islamic law on which he or she married) or to go for a private settlement with no force of law.

21 SK Rashid 'On the teaching of Islamic law in Nigeria' in SK Rashid Islamic law in Nigeria: Application and teaching (1986) 90.

22 Zamfara State of Nigeria, Law 5 of 1999 enacted in October 1999, published in Zamfara State of Nigeria Gazette of 15 June 2000 A1-30.

23 'The birth of Shari'a' The Guardian (Lagos) 30 October 1999, reproduced in Ostien (n 12 above) vol I, Preface to Volumes I-5, ix.

24 Independent National Electoral Commission Nigeria 'INEC: Report on the 2011 General Election', http://www.inecnigeria.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/07/report-on-the-2011-General-elections (accessed 30 April 2014). [ Links ]

25 Federal Government White Paper on the Report on Area Courts, Federal Ministry of Information, 1977 No 5 5.

26 Adegbola v Folaranmi James & Tiamiyu Lawanson (1921) 3 NLR 89.

27 LB Curzon English legal history (1979) 57.

28 1880 6p.D 35 53, as cited by RH Graveson Conflict of laws: Private international law (1974) 244.

29 UK Appeal Case 406, cited in Oloyede (n 17 above) 32.

30 As above.

31 The Nation (Lagos) 26 December 2012 46.

32 See 'Nigerian Christians are treated as second class citizens - Oritsejafor' Vanguard 27 July 2013.

33 Oloyede (n 17 above) 29-38; IO Oloyede 'Secularism and religion; Conflict and compromise - An Islamic perspective' (1987) 18 Islam and the Modern Age 121-138.

34 EL Cross (ed) The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church (1978) 132.

35 Dickson v Maras Ubani (1961) All NLR 277.

36 Sec 10 of the 1799 Constitution of Nigeria, incorporated in the 1999 Constitution.

37 Chamber's 20th century dictionary (1983).

38 The Lexicon Webster dictionary (1973) Vol II:863.

39 University of Ibadan, Question Paper for LPB 402 held on 15 April 2000.

40 K Akinlade Owo Eje (1976).

41 S Eso-Oluborode lyawo Alarede (1993).

42 O Taiwo et al Macmillian primary English course, Pupils Book 5 (1996).

43 Pew Forum (n 4 above) 64.

44 Pew Forum (n 4 above) 34 (on the persistence among Africa's Muslims and Christians of African traditional religion practices of juju amulets to ward off the 'evil eye' of perceived enemies).

45 Pew Forum (n 4 above) 176 (on African belief in miracles).

46 Pew Forum (n 4 above) 211 (on African reports of witnessing divine healing of an illness or injury).

47 'EFCC: Former PHB boss Atuche used stolen funds to pay N45m church tithes' Sahara Reporters 26 September 2012, http://saharareporters.com/news-page/efcc-former-phb-boss-atuche-used-stolen-funds-pay-n45m-church-tithes (accessed 30 April 2014).

48 The Vanguard (Lagos) 30 August 2011; The Leadership (Abuja) January 2012; The Nation (Lagos) 28 March 2012 57; Daily Post (Lagos) 22 June 2012.

49 J Herskovits 'In Nigeria, Boko Haram is not the problem' The New York Times 2 January 2012.

50 As above.

51 MH Kukah 'An appeal to Nigerians' (delivered at NTA and Radio Nigeria on 10 December 2011) The Guardian (Lagos) 17 January 2012.

52 'Police arrest prostitute over alleged attempt to burn down church' Vanguard (Lagos) 30 August 2011.

53 M Haruna 'Still playing dangerous politics with Boko Haram' The Nation (Lagos) 64; This Day (Abuja) 31 July 2000.

54 n 24 above.

55 The Governor of Benue State as widely reported in the national newspapers in December 2012.