Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.72 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2023/vn72a13810

"Soldiers against gangsters?": Evaluation of the impact of the army deployment against gang violence on homicides in the Cape Flats

Ignacio CanoI; Anine KrieglerII; Douglas ScottIII; Zephaniah Sabela NtshekisaIV

Iignaciocano62@gmail.com

IIaninek@gmail.com

IIIdouglas.i.scott@gmail.com

IVzeebeetriplek77@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The debate on militarisation of domestic security around the world Is mostly normative and conceptual, but there are few estimates of the direct impact of the use of military forces in public security tasks. This paper assesses the impact on local homicides of the 2019 deployment of the South African National Defence Force in police station areas in Cape Town, a measure taken to stem gang violence. It uses an interrupted time-series approach to estimate the effect by comparing murder counts in relevant precincts before and during the deployment, compared to precincts with similar murder rates and socioeconomic characteristics. Results show that there was an apparent initial reduction in the month in which the measure was taken, but the presence of the army was not associated with a significant decrease in homicides over the deployment period.

Keywords: homicide, murder, impact of army, militarisation, South Africa.

Introduction

South Africa has long had one of the highest rates of criminal violence in the world. Its recorded murder rate is more than six times the global average and has been above 30 per 100,000 since the 1960s.1 The City of Cape Town hosts even higher levels of violence. Its murder rate increased in recent years, from 44 per 100,000 in 2010 to 73 per 100,000 in 2019.2 This is largely attributed to its criminal gangs, which range from powerful drug-selling organisations with links to global organised crime to local coalitions of belligerent schoolboys3 and schoolgirls.4

Gang activity in South Africa is a long-standing phenomenon,5 but triggers periodic surges in violence especially in the Western Cape province. In 2013, a series of shootings led to the temporary closure of 14 schools in one particularly gang-affected area.6 Fuelled by thousands of firearms diverted from the police,7 turf battles in 2018 led parts of the area known as the Cape Flats, only a 20-minute drive from the city centre, to be classified as "red zones", meaning that ambulance workers would not enter without a police escort.8

The premier of the Western Cape made requests for military intervention to the national government from at least July 2012.9 She publicly stressed that the province had constitutionally limited powers to address the gang situation,10 and the issue became increasingly subject to party political contestation, still ongoing,11 over federalism and the devolution of policing mandates to the provinces.12 Amid another apparent surge in gang violence and calls from members of local Community Policing Forums (CPFs) for the declaration of a state of emergency,13 military personnel from the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) were ultimately deployed to parts of Cape Town in July 2019 to support the South African Police Service (SAPS) in operations to restore law and order.14 This was known as Operation Lockdown (not to be confused with the COVID-19 lockdown implemented country-wide shortly afterwards). The initial deployment period was to be from 18 July 2019 to 16 September 2019 but was subsequently extended to 31 March 2020.15

This was not the first use of the military in this kind of supporting role to the SAPS, as for example attested by Operation Fiela-Reclaim in 2015. However, the partisan context around Operation Lockdown heightened public interest. While the move appeared to be welcomed by at least some in gang-affected communities,16 there were also concerns about the long-term implications of the use of the military to perform law and order functions.17 Times of crisis, when the public cries out for government to "do something", can have a "ratchet effect" on government powers, which may not later return to their pre-crisis dimensions.18 Many were also sceptical of the soldiers' prospects of success against the decades-old, entrenched network of gangs and their underlying socioeconomic drivers. Similar previous operations had shown only tentative evidence of only short-lived effects.19

The incident would have presented an ideal opportunity to evaluate a natural experiment in police militarisation, were it not for the interference of COVID-19 from early 2020. Pandemic-associated control measures had an independent and major impact on crime levels.20 Moreover, the SANDF was redeployed domestically to support the enforcement of the national lockdown regulations, starting on 26 March 2020.21 The army stayed in some areas, but with a different purpose, while also spreading to many others. An estimation of their sustained impact therefore became impossible.

This paper nonetheless provides an empirical estimation of the impact of the 2019 SANDF deployment to certain high-murder police station areas in Cape Town. It uses an interrupted time-series approach with a control group to estimate the intervention's effect by comparing official police murder figures for the months before and during the deployment. This can inform future policy decisions in this and similar contexts and also contribute to global debates on the militarisation of public security.

Police militarisation

The deployment of the army to quell gang violence in Cape Town is a particularly clear and direct instance of the militarisation of policing. A distinction between police responsibility for internal security and military responsibility for external threats to national security is considered a "hallmark feature of the modern nation-state".22 Yet recent years have seen a growing debate on the blurring of these lines in many countries. The global "war on terror" led many states to rely increasingly on their armed forces for surveillance and protection inside their own borders.23 Policing militarisation came to greater popular attention in the United States in the wake of events in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, where the fatal shooting of an unarmed African American by police led to a series of protests.

In settings in the global North, the observed militarisation has been largely indirect, encompassing shifts in the domains of gear/technology, protocols/procedures for community interaction, military tactics, officer culture/mindset, and training and requirements.24 There is concern about law enforcement's shifting identity from guardians to warriors, and a narrative of the "bobby on the beat" being replaced by "camouflage wearing brutes".25

This has raised normative debates about the implications of waging "war on crime", the relationship between police militarisation and professionalism, and the use and abuse of force.26 Some have argued that the dichotomy is false, that war and policing should be understood on a continuum of state power, and that "police power's intimate links with military power is in no way new or aberrational".27 There is also ongoing dispute as to the impact of police militarisation on crime, with some finding that some measures of militarisation do seem to improve the capabilities of police to deter crime,28 but others finding no such effect.29 Findings have also been mixed as to the impact of militarisation on police use of lethal force.30

In parts of the global South, especially in the most violent and unequal places of the world, the trend has been towards direct militarisation. Several countries in Latin America have resorted to using military or paramilitary units in large-scale operations with the aim of retaking domestic territories controlled defacto by criminal groups.31 There is evidence that this may have produced an increase in the use of lethal force by state agents and also in overall levels of violence.32

The dichotomy between police and army was never particularly clear in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. These contexts differ from their Northern counterparts in their political histories as settler colonial states and in the starkness of their racial, economic and social inequalities.33 Their strategic paradox is that their most critical security challenges are internal.34 In the communities where military power has in recent years been used against the population in the name of crime control, the police have arguably "never been peace officers;...instead, they have used their role as part of the security apparatus of the state with little regard for the citizenship, human rights and the protections promised to communities by virtue of their equality before the law".35

South Africa is a case in point. Against what was considered the "total onslaught" of subversive elements, the Apartheid state conducted a "total strategy", meaning the co-ordination of "all aspects of national life - the military, economic, political, sociological, technological, ideological, psychological and cultural - in an integrated defence of the nation".36 Members of the police performed military-type duties in neighbouring countries, while the army was also used domestically to suppress "unrest" in black urban townships.37 The police force, with its armoured vehicles (known as Casspirs), live ammunition, and formula of skop, skiet en donder (kick, shoot and hammer), were the most visible representation of the Apartheid state.38

After the end of Apartheid in 1994, the police force was to transform into a police service. Efforts were made to form an organisation that was not only racially representative, but also community oriented, human rights based, and demilitarised.39 Yet its traditions, hierarchical structure, and the "war on crime" discourse of South African political leadership have perpetuated the militarisation of the SAPS.40Among other things, this has manifested in a practice of large-scale, "high-density" operations, involving "a sudden and noticeable increase in the number of police personnel and concentrated police actions in targeted areas."41 These operations (with fierce codenames, such as Crackdown, Slasher, or Iron Fist) use cordon-and-search tactics to "capture 'wanted' persons and seize illegal weapons and other contraband".42

Not only have these operations been militaristic in character, but many (including Operation Fiela-Reclaim, launched in 2015 in response to xenophobic violence and crime) have involved the SANDF.

Legally, the soldiers have the same powers and authority as the police, excluding the investigation of crime,43 but they typically focus on providing the police with protection and logistic and personnel support toward maintaining operational perimeters and roadblocks.44 The Minister of Police described Operation Lockdown as consisting of "all role players such as the various SAPS units, Metro police, traffic services, SANDF and in some instances scores of neighbourhood watch members and volunteers ... descending week after week on a number of targeted precincts in an effort to create safety for all [through] [r]aids, operations, cordon and searches, vehicle checkpoints, roadblocks as well as search and seizures ... particularly on weekends when most criminal acts occur."45 The SANDF's contribution was to be "a) Troops for cordon and search, strong points in hot spots, observation, foot and vehicle patrols; b) Air support for trooping and identification of substance manufacturing labs; and c) Any other operations that may be determined from time to time".46

Gangs have often been a target of these large-scale operations, as for example in the 2012 Operation Combat, which aimed to "dislodge and terminally weaken the capacity of the gangs to operate in the selected communities".47 Thus, the 2019 deployment of the SANDF to the Cape Flats is an extension of this South African policing practice. Still, it is symbolically remarkable. The "gang" in Cape Town, as elsewhere, is a category of discourse that allows institutions to act in specific ways, which, even before the army deployment bore striking resemblances to counterinsurgency strategies.48 To deploy the national defence force against domestic targets marks its targets as beyond the state realm. It must use its military capacity to "take back" dominion over a territory that was lost or never fully held. The Minister of Police noted that Operation Lockdown formed part of efforts to "stamp the authority of the state in the Western Cape".49 Indeed, gangs in parts of the Cape Flats arguably operate as a form of organised counter-government, fulfilling certain economic and social functions that the state does not, even as it perpetuates their communities' marginalisation.50

Such normative discussions of police militarisation are important, but the victims of Cape Town's gang violence may reasonably be more interested in whether it works. That is what this article proceeds to estimate.

Methodology

Analytic design

Given that the intervention areas had already been established, an experimental design was not possible. An interrupted time-series analysis with a control group51 was selected to evaluate the impact of army deployment on local murders. The interrupted time-series allows us to see how murder levels changed during the intervention and compare this to control areas with similar characteristics but where the army was not deployed. They provide a kind of counterfactual of what might have happened in the intervened areas, had the army not been deployed.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was the monthly number of murders recorded by the police in each of the communities. In this article we use the word "murder", which is the legal term used in criminal records in South Africa, rather than "(intentional) homicide", which is more common internationally.52 There is a slight conceptual, and in some places, legal distinction between the two, but criminological research typically treats them as synonymous. Homicide or murder rates have been selected as the primary or only dependent variable in the overwhelming majority of quantitative research on violent crime causation.53 Murder is relatively consistent in lay and cross-jurisdictional understanding, and its "indisputable physical consequences manifested in the form of a dead body also make it the most categorical and calculable".54 This is why the United Nations and many others consider it a "robust indicator of levels of security" and a good proxy for violent crime more broadly.55

Publicly available precinct-level murder data were collected from the SAPS56 for the period from April 2016 to February 2020. Army deployment against gangs took place from mid-July 2019,57 to the start of the COVID-19 lockdown starting on 26 March 2020.58 The pandemic lockdown resulted in the army being redeployed more widely to support the enforcement of the lockdown.59

The series comprises 39 months before the deployment and eight months after it began. This is a reasonably long series before the intervention, but a short one after it. Unfortunately, the arrival of COVID-19 and its corresponding lockdowns would make it difficult to differentiate the effects of the presence of the army against gangs, its deployment to enforce COVID-19 regulations, other lockdown conditions, or an interaction of these elements. Data has shown that several crime types, particularly murder, were strongly affected by lockdowns, producing a sudden downward trend.60 The analysis here therefore stops in February 2020 so that COVID-19 does not cloud the impact estimation of the original army intervention against the gangs.

These kinds of operations might also have delayed effects. However, beyond the usual methodological challenges involved in estimating such effects, the arrival of COVID-19 and the subsequent limitation of our series makes it impossible to even attempt to measure them in this case.

Independent variable: deployment areas

When approval for the army's support to the SAPS in Cape Town was finally announced, numerous media reports specified the targeted areas as Bishop Lavis, Delft, Elsies River, Khayelitsha, Kraaifontein, Manenberg, Mfuleni, Mitchells Plain, Nyanga, and Philippi.61 Although the criteria for this selection were not publicised, these areas are all known for gang activity and high murder levels. The Minister of Police told Parliament that the army would be deployed Inter alia to Bishop Lavis, Delft, Gugulethu, Harare, Khayelitsha, Kraaifontein, Mfuleni, Mitchells Plain, Nyanga, and Philippi East.62 These lists are similar but not identical. The words "inter alia" also indicate that this was not an exhaustive list.

Formal requests were submitted to both the SAPS and the Department of Defence for information on their co-deployment locations. Despite over a year of correspondence under the provisions of the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000, which intends to give effect to the constitutional right of access to information held by the state, this was not forthcoming. A request was also submitted to a Member of Parliament and member of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Police, but this, too, was fruitless. Relevant police stations were also contacted by phone, but they declined to confirm or deny SANDF deployment in their area. No reliable, official government record with this information could be located. It was therefore necessary to verify it independently. This was done by contacting the leaders of Community Policing Forums (CPFs). CPFs are official committees of residents who volunteer to represent their community and act as civilian oversight for police operations in their area. Police stations did provide contact details for the CPF chairperson in their area.

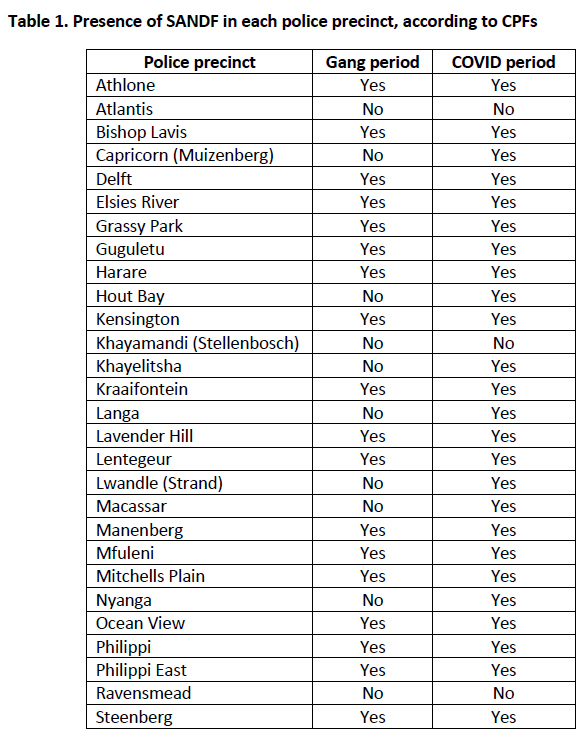

The leaders of CPFs of 28 police station areas (including all those that had been mentioned in any of the sources, plus other likely candidates across the Cape Flats) were contacted by phone and asked whether the SANDF had been deployed in their precinct during the gang intervention period (June 2019 to February 2020) and also during COVID-19. This made it possible to determine which areas could be considered for the intervention and control groups, as follows.

We believe that this strategy is reliable, given that CPF leaders are not simply ordinary residents, but active participants within the local structures of civilian police oversight. They have regular, direct interaction with the police in their areas and likely would have discussed SANDF presence with the police and within their structures at the time. None of them showed any doubts or had any difficulty differentiating between the military deployment against gangs and their later deployment during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

In addition to an official, authoritative record of deployment locations, it would have been of enormous analytical value to have access to information on their scale and precise nature. It is likely that the different areas saw variations in the size of the military presence, i.e. the "dosage" of the intervention, and in the specific roles that the military carried out. Unfortunately, this information was also impossible to obtain.

Independent variable: intervention and control groups

Having established as definitively as possible where the army anti-gang intervention took place, this information was combined with murder and demographic data to select the areas for analysis. Data from SAPS and a projection of population from the 2011 national Census63 were used to estimate precinct-level murder rates per 100,000 inhabitants for the 2017/2018 reporting year, just prior to the intervention. Census data was also used to calculate levels of income, average educational attainment, and unemployment within each of the 61 police precincts in the City of Cape Town. These variables were recorded into quintiles to facilitate comparison.

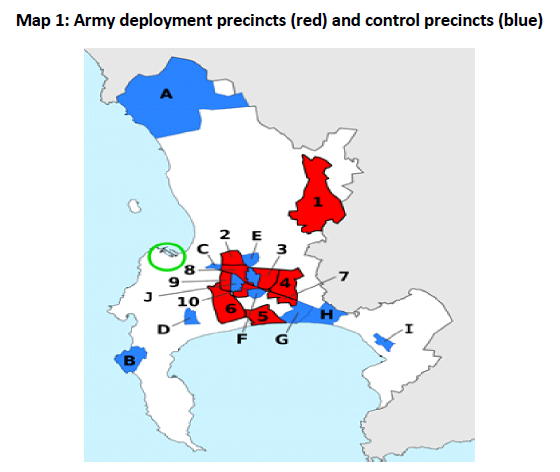

The total of 20 precincts selected for analysis are those with the highest murder rates in the city, all recording a rate of over 60 per 100,000. The only exception was Philadelphia, which was disregarded due to its rural nature and very small population. The 13 intervention precincts were Bishop Lavis, Delft, Elsies River, Gugulethu, Harare, Kraaifontein, Manenberg, Mfuleni, Mitchells Plain, Ocean View, Philippi, Philippi East, and Steenberg. The seven control precincts not only share these high murder rates, but also a similar profile in terms of low levels of income, low levels of average schooling, and high unemployment rates. The control group is composed of the following communities: Nyanga, Khayelitsha, Ravensmead, Langa, Lwandle, Atlantis and Macassar.

The following table presents a summary of those results, with all precincts within Cape Town ordered by murder rate. Communities that received army deployment are marked in red and communities chosen as control groups are marked in blue.

In short, both intervention and control precincts are characterised by high rates of murder, low income and educational levels and high unemployment. Furthermore, 10 areas within the target communities and three within the control group are part of the 25 precincts that the Western Cape Department of Community Safety considers priority gang police stations in the province,64 suggesting that they also see similarities in terms of gang activity levels.

Results

The monthly number of murders per community, including both intervention and control areas for the period from April 2016 to February 2020, varies from 0 (in 23 cases) to a maximum of 47 (1 case), with an average of 9.6. The histogram (graph 1) shows that the distribution of monthly murders by community is relatively normal, albeit with a longer right tail, as expected, since the left side is truncated at 0 and the right side is not.

Although the distribution is not exactly normal, it was deemed close enough to be able to apply standard linear models. The log transformation did not achieve full normality either.

An initial, visual inspection was conducted. The monthly evolution of the consolidated number of murders in intervention and control areas over the period is shown in graph 2.

Visually, it appears that there was a reduction of murders in the intervention precincts exactly at the month where deployment started, July 2019. There is also a reduction in the control areas in that same month, but a very small one. After this apparent initial effect, both series appear to evolve in a similar way over the remaining months. The correlation coefficient between both series over the whole period is of a medium size and highly significant (0,566, n=47, p<0.01), which confirms that both figures are subjected to similar time effects, whether due to seasonality or other events or influences.

Graph 3 shows the same data but smoothed through a moving average (each case is the average of itself, the two preceding and the two following ones) so that there is less monthly variation and noise, and trends can be better observed. The disadvantage is the loss of the first two and last two cases.

The smoothed series appears to confirm the reduction in the short post-intervention series in the thirteen communities where the army was deployed, but also in the seven control communities. This means that in order to show the impact of the army deployment, intervention communities will need to show a stronger decrease than control ones.

The correlation coefficient between the number of murders and the number of months since the beginning of the series before the intervention is significant: 0,323 (p<0.05). This means there was an ascending linear trend whereby murders were increasing before July 2019, when the army was deployed. In fact, the correlation was significant only for intervention communities (r=0.364), but not for control ones (r=0.138 and p<0.05).

Hence, the linear model to estimate the impact of the intervention incorporates a linear trend. The dependent variable of the model is the monthly number of murders in each community. The independent variables are:

a) Community, as a fixed factor, so that differences in levels of murder between communities, which may be due to several factors including population size, may be accounted for. As shown in Table 3, the average number of murders vary considerably between communities.

b) A dummy variable to indicate the presence of the army, which is equal to 1 in the months between July 2019 and February 2020 in intervention communities, and is equal to 0 otherwise.

c) A serial number that measures the number of months since the beginning of the series, to incorporate the existence of a linear trend over time.

The results of the model are shown in Table 4. As far as the fixed factor for the community is concerned, only the first and the last coefficients are shown for the sake of simplicity.

The linear trend is statistically significant, which confirms that there was an upward trend before the intervention.

The most relevant result for our analysis is that the impact of the army is not significant. In other words, despite the apparent reduction of murders in the first month that could be seen on the graph, there is no evidence that the presence of the army reduced murders in the affected communities when compared with similar ones where the army was absent.

Conclusion

The 2019 deployment of the army to support the police in anti-gang operations in parts of Cape Town was both long-awaited and controversial. Within its first month, the Police Minister reported that over 1,000 people had been arrested, of whom 806 were already "in the system" and wanted for other crimes.65 The Minister of Defence and Military Veterans claimed it as a success, in that "where the other state entities had lost access into the areas engulfed with violence, the defence force has made it possible for them to access such areas as part of their service delivery mandate".66 Local CPFs were less sure that it was working.67 Months later, some community activists were saying, "Here comes the army, there goes the army," and "Nothing has really changed".68

Yet no clarity emerged, in either popular or scholarly view, on whether there had in fact been any positive impact on levels of violence. The analysis in this paper suggests that there does appear to have been a reduction in murders in the month when the deployment started but found no evidence that the army presence significantly reduced murders in the affected communities over the deployment period, as compared with similar ones where the army was absent. Gang violence in Cape Town and in similar contexts, such as Latin America and other countries in the global South, will doubtless surge again. This research should inform ongoing debates on the appropriateness and effectiveness of further militarisation of public security.

Notes

1 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Study on Homicide 2019: Homicide Trends, Patterns and Criminal Justice Response (Vienna, 2019). [ Links ]

2 South African Cities Network, The State of Crime and Safety in SA Cities (Johannesburg, 2020). [ Links ]

3 D. Pinnock, Gang Town (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2016). [ Links ]

4 D. Dziewanski, "Femme Fatales: Girl Gangsters and Violent Street Culture in Cape Town," Feminist Criminology, 15, no. 4 (2020): 438-463, https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085120914374. [ Links ]

5 G. Kynoch, "From the Ninevites to the Hard Livings Gang: Township Gangsters and Urban Violence in Twentieth-Century South Africa," African Studies, 58, no. 1 (1999): 55-85. [ Links ]

6 V. John, "Fourteen Cape Town Schools to Close After Surge in Gang Violence," Mail & Guardian, 14 Aug. 2013, https://mg.co.za/article/2013-08-14-fourteen-cape-town-schools-to-close-after-surge-in-gang-violence/.

7 M. Thamm, "When Hell Is Not Hot Enough: A Top Cop Supplied Weapons to Country's Gangsters and Right Wingers," Daily Maverick, 4 July 2016, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2016-07-04-when-hell-is-not-hot-enough-a-top-cop-who-supplied-weapons-to-countrys-gangsters-and-right-wingers/#.WKwVPW995hE.

8 A. Hendricks, "Paramedics Seen As 'Soft Targets, Easy Pickings' by Criminals on Cape Flats," News24, 16 Aug. 2018, www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/paramedics-seen-as-soft-targets-easy-pickings-by-criminals-on-cape-flats-20180816.

9 Western Cape Government, "Premier Zille Replies to President Zuma's Response on Deployment of SANDF," 16 July 2012, www.westerncape.gov.za/news/premier-zille-replies-president-zumas-response-deployment-sandf.

10 Western Cape Government, "Fighting Crime: We Can Only Win by Working Better Together," 18 Sept. 2012, www.westerncape.gov.za/news/fighting-crime-we-can-only-win-working-better-together.

11 J. Gerber, "The Policing Debate: Western Cape Wants It Devolved to Provinces, ANC Insists on Central Control," News24, 9 Sept. 2021, www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/the-policing-debate-western-cape-wants-it-devolved-to-provinces-anc-insists-on-central-control-20210909.

12 H. Zille, "Inside Government: The Puzzle of Gangs, Drugs, Police and Politics in the WC," 15 Oct. 2015, www.westerncape.gov.za/news/inside-government-puzzle-gangs-drugs-police-and-politics-wc.

13 V. Ludidi, "Policing Forums Demand State of Emergency in 'Gang-Infested' Areas," GroundUp, July 2019, www.groundup.org.za/article/cpf-demand-state-emergency-be-declared-gang-infested-areas/.

14 South African Police Service, "Budget Vote Speech Delivered by Minister of Police Bheki Cele 11 July 2019", www.saps.gov.za/newsroom/msspeechdetail.php?nid=21257.

15 Office of the President of South Africa, President's Minute, no. 346/2019, 2019; Office of the President of South Africa, President's Minute, no. 411/2019, 2019.

16 K. de Greef, "As Gang Murders Surge South Africa Sends Army to Cape Town and the City Cheers," New York Times, 13 Aug. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/08/13/world/africa/cape-town-crime-military.html.

17 L. Heinecken, "The Army Is Being Used to Fight Cape Town's Gangs. Why It's a Bad Idea," The Conversation Africa, 17 July 2019, https://theconversation.com/the-army-is-being-used-to-fight-cape-towns-gangs-why-its-a-bad-idea-120455.

18 A. R. Hall, and C. J. Coyne, "The Militarization of US Domestic Policing," Independent Review, 17, no. 4 (2013): 485-504, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2122384.

19 G. Lamb, "Jagged Blue Frontiers: the Police and the Policing of Boundaries in South Africa," Doctoral thesis, University of Cape Town, 2017. [ Links ]

20 Department of Community Safety, "Violent Crime in 11 Priority Areas of the Western Cape During the COVID-19 Lockdown" (2020), https://www.westerncape.gov.za/files/20200629_violent_crime_during_lockdown_-_report_final_with_recommendations_1.pdf.

21 Office of the President of South Africa, "Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces to Send Well Wishes to Police Services and National Defence Force," 26 March 2020, www.thepresidency.gov.za/press-statements/commander-chief-armed-forces-send-well-wishes-police-services-and-national-defence.

22 P. B. Kraska, "Police Militarization 101," in Critical Issues in Policing: Contemporary Readings, ed. R. Dunham, G. Alpert, and K. McLean, K. (Illinois, USA: Waveland Press, Inc., 2021): 445-458.

23 A. Esterhuyse, "The Domestic Deployment of the Military in a Democratic South Africa: Time for a Debate," African Security Review, 28, no. 1 (2019): 3-18, https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2019.1650787. [ Links ]

24 M. Simckes, et al. "A Conceptualization of Militarization in Domestic Policing," Police Quarterly, 22, no. 4 (2019): 511-538, https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611119862070. [ Links ]

25 C. McMichael "Pacification and Police: A Critique of the Police Militarization Thesis," Capital and Class, 41, no. 1 (2017): 118, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309816816678569.

26 T. Steidley and D. M. Ramey, "Police Militarization in the United States," Sociology Compass, 13, no. 4 (2019): 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12674. [ Links ]

27 McMichael, "Pacification and Police": 118.

28 B. V. Bove and E. Gavrilova, "Police Officer on the Frontline or a Soldier? The Effect of Police Militarization on Crime," American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 9, no. 3 (2017): 1-18. [ Links ]

29 J. Mummolo, "Militarization Fails to Enhance Police Safety or Reduce Crime but May Harm Police Reputation," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, no. 27 (2021): e2109160118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2109160118. [ Links ]

30 E. Lawson, "TRENDS: Police Militarization and the Use of Lethal Force," Political Research Quarterly, 72, no. 1 (2019): 177-189, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918784209; [ Links ] W. M. Koslicki, D. W. Willits, and R. Brooks, "Fatal Outcomes of Militarization: Re-Examining the Relationship Between the 1033 Program and Police Deadly Force," Journal of Criminal Justice, 72 (Dec. 2020): 101781, https://doi.org/10.1016/jjcrimjus.2021.101781.

31 V. Felbab-Brown, "Bringing the State to the Slum: Confronting Organized Crime and Urban Violence in Latin America. Lessons for Law Enforcement and Policymakers," Latin America Initiative at Brookings, (Dec. 2011); URVIO, Revista Latinoamericana de Seguridad Ciudadana Departamento de Asuntos Públicos - FLACSO Sede Ecuador, vol. 12., (Dec 2012), ISSN: 1390-3691.

32 A. Antillano and K. Ávila, "¿La Mano Dura Disminuye Los Homicidios? El Caso De Venezuela," Revista CIDOB d'Afers Internacionals, 116 (2017): 77-100, https://doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2017.116.2.77; L. Atuesta Becerra, "Militarización De La Lucha Contra El Narcotráfico: Los Operativos Militares Como Estrategia Para El Combate Del Crimen Organizado," in Las Violencias: En Busca De La Política Pública De La Guerra Contra Las Drogas, ed. L. Atuesta Becerra and A. Madrazo Lajous (Colección Coyuntura y Ensayo, Ciudad de México: CIDE 2019); C. Silva Forné, C. Pérez Correa, & R. Gutiérrez, "Uso De La Fuerza Letal. Muertos, Heridos Y Detenidos En Enfrentamientos De Las Fuerzas Federales Con Presuntos Miembros De La Delincuencia Organizada," Desacatos: Revista de Antropología Social, 40 (2012): 47-64.

33 Z. Stuurman, "Policing Inequality and the Inequality of Policing: A Look at the Militarisation of Policing Around the World, Focusing on Brazil and South Africa," South African Journal of International Affairs, 27, no. 1 (2020): 44, https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2020.1748103.

34 Esterhuyse, "The Domestic Deployment of the Military."

35 Stuurman, "Policing Inequality": 49.

36 D. Hansson, "Changes in Counter-Revolutionary State Strategy in the Decade 1979 to 1989," in Towards Justice? Crime And State Control in South Africa, eds. D. Hansson and D. Van Zyl Smit (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1990): 30.

37 D. Bruce, "New Wine from An Old Cask? The South African Police Service and the Process of Transformation," Paper presented at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (New York, 2002) www.csrv.org.za.

38 T. B. Hansen, "Performers of Sovereignty: On the Privatization of Security in Urban South Africa," Critique of Anthropology, 26, no. 3 (2006): 279-295. [ Links ]

39 G. Lamb, "Safeguarding the Republic? The South African Police Service, Legitimacy and the Tribulations of Policing a Violent Democracy," Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56, no. 1 (2021): 92-108, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909620946853.

40 G. Lamb, "Police Militarisation and the "War on Crime" in South Africa," Journal of Southern African Studies, 44, no. 5 (2018): 933-949. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2018.1503831.

41 G. Lamb, "Fighting Fire with an Inferno: The South Police Service and the 'War' on Crime," Sur - International Journal on Human Rights, 12, no. 22 (2015): 87.

42 Lamb, "Police militarisation": 944.

43 Section 19 of the Defence Act, No. 42 of 2002.

44 M. Montesh and V. Basdeo, "The Role of the South African National Defence Force in Policing," Scientia Militaría, South African Journal of Military Studies, 40, no. 1 (2012): 71-94. doi: 10.5787/40-1-985.

45 Ministry of Police, "Police Minister is Encouraged by the Declining Murder Rate and Number of Arrests in the Western Cape," Media Statement, 16 Oct. 2019, www.saps.gov.za/newsroom/msspeechdetailm.php?nid=22854.

46 B. Cele, "Minister of Police Budget Speech (SAPS & I PI D) & Responses by IFP, ACDP & DA," Parliament of South Africa, 11 July 2019, Parliamentary Monitoring Group. www.saps.gov.za/newsroom/msspeechdetail.php?nid=21257

47 South African Police Service, Western Cape, "Western Cape Gang Strategy: Operation Combat," 19 August 2015, https://static.pmg.org.za/150819GangStrategy.pdf.

48 S. Jensen, "The Security and Development Nexus in Cape Town: War on Gangs, Counterinsurgency and Citizenship," Security Dialogue, 41, no. 1 (2010): 77-97.

49 Ministry of Police, "Police Minister is Encouraged".

50 A. Standing, The Social Contradictions of Organised Crime on the Cape Flats, Institute for Security Studies (2003): 74, https://issafrica.org/research/papers/the-social-contradictions-of-organised-crime-on-the-cape-flats.

51 W. R. Shadish, T. D. Cook, and D. T. Campbell, Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference (Houghton: Mifflin and Company, 2002).

52 In South Africa, "murder" is defined as the intentional unlawful killing of another human being, whereas "culpable homicide" is defined as the negligent unlawful killing of another human being. The SAPS does not release statistics on culpable homicide, which is roughly equivalent to "involuntary manslaughter" in other jurisdictions. See Kemp et al, "Criminal law in South Africa," 1st ed, Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa (2012): 30.

53 M. F. Aebi and A. Linde, "Long-Term Trends in Crime: Continuity and Change" in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Crime and Criminal Justice, eds. P. Knepper and A. Johansen (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016).

54 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Study on Homicide 2011 (Vienna, 2011).

55 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Study on Homicide 2013 (Vienna, 2013).

56 South African Police Service, "Annual Stats 2019/20," www.saps.gov.za/services/crimestats.php, accessed 14 November 2020.

57 J. Burke, "South African Army Sent into Townships to Curb Gang Violence," The Guardian, 19 July 2019, www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/19/south-african-army-townships-gang-violence.

58 Office of the President of South Africa, "Commander-in-Chief".

59 Parliamentary Monitoring Service, "SANDF deployment & involvement in COVID-19 measures; Complaints against SANDF during lockdown; with Minister", Parliament of South Africa, Defence committee meeting summary, 22 April 2020, https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/30107/.

60 A. Faull, J. Kelly, and A. Dissel, "Lockdown Lessons: Violence and Policing in a Pandemic," Southern Africa Report, Institute of Security Studies, 44 (March 2021).

61 J. Gerber, "South Africa: This is Where the Army Will Be Deployed in Cape Town," News24Wire, 12 July 2019, https://allafrica.com/stories/201907120657.html; Cape Business News, "Where the Army Will Be Deployed in Cape Town," 12 July 2019, www.cbn.co.za/featured/where-the-army-will-be-deployed-in-cape-town/.

62 Cele, "Minister of Police Budget Speech".

63 Statistics South Africa, "Census 2011: Community Profile Database," DVD database (2012), www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=3839.

64 Department of Community Safety, Western Cape Crime Report 2018/19: Department of Community Safety, 2019, www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/communitysafety/crime_over-view_report-_western_cape_analysis_15-16.pdf.

65 K. Somdyala, "Western Cape's Weekend Murders Down, But Concern Grows Over the Army's Effectiveness." News24, 19 Aug. 2019, www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/News/western-capes-weekend-murders-down-but-concern-grows-over-armys-effectiveness-20190819.

66 E. van Diemen, "SANDF's Cape Flats Deployment a 'Success', But Boots, Barrels and Bullets Won't End Gangsterism, Says Defence Minister," News24, 27 Aug. 2019, www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/News/sandfs-cape-flats-deployment-a-succss-but-boots-barrels-and-bullets-wont-end-gangsterism-says-defence-minister-20190827.

67 K. Palm, "Govt Hails SANDF Deployment in CT a Success, CPFs Disagree," Eyewitness News, 28 Aug. 2019, https://ewn.co.za/2019/08/28/govt-hails-sandf-deployment-in-ct-a-success-cpfs-disagree.

68 A. Hendricks, "Hanover Park Resident: 'There Comes the Army, There Goes the Army," GroundUp, 13 March 2020, www.groundup.org.za/article/hanover-park-resident-there-comes-army-there-goes-army/.