Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.71 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2022/vn71a12709

Prison protests in South Africa: A conceptual exploration

Lukas Muntingh1

ABSTRACT

This article explores the nature and causes of prisoner protests, looking at it first from a sociological perspective and second, a rights perspective. The fact that people end up in prison following due process does not mean that their imprisonment is not a contested arena in the sense that prisoners are generally aware of their rights, even when curtailed. Importantly, this curtailment has boundaries - prisoners do not lose all their rights and it seems that this particular issue is frequently the locus of tension, and sometimes conflict, between prisoners and prison administration. There is nothing in South African law prohibiting prisoners from protesting as recognised by s 17 of the Bill of Rights. However, prisoners, with reference to the right to free speech and the right to peaceful demonstration, find themselves in a situation where they can claim these rights, but the enabling legislation is not only lacking, but there are strong indications that the operational procedures prevent them from exercising these rights.

Introduction

Although accurate data is hard to come by, the overall impression is that South Africa's prisons are not characterised by frequent and large-scale prison protests, as is the case in some Latin American countries.2 In South Africa, the most widespread prison protests occurred in the run-up and months after the 1994 elections, where protests occurred at 53 prisons and a total of 37 prisoners died.3 Those protests were first caused by uncertainty as to whether prisoners would be able to participate in the elections (which they ultimately did). Following the elections, there was a further expectation of a general amnesty being granted. An answer from government was not forthcoming, resulting in increased tensions and ultimately violent protests. Political events from 1990 to 1994 also had their impact on prisons and the number of unrest-related incidents in prisons increased from eight in 1990 to 275 in 1994.4 Other prisoner protests on record appear to relate, first, to sentence and parole administration and, second, to the treatment of prisoners.

This article explores the nature and causes of prisoner protests, looking at it first from a sociological perspective and secondly, a rights perspective. Prison protests should be seen distinct from prison violence,5 as not all protests are violent (e.g. hunger strikes) and not all prison violence has a protest agenda. The fact that people end up in prison following due process does not mean that their imprisonment is not a contested arena, in the sense that prisoners are generally aware of their rights, even when curtailed. Importantly, this curtailment has boundaries - prisoners do not lose all their rights and it seems that this particular issue is frequently the locus of tension, and sometimes conflict, between prisoners and the prison administration.

What are prison protests?

The Kriegler Commission, which investigated the 1994 South African prisoner protests, referred to 'unrest-related incidents' and larger and longer protests are commonly referred to as 'riots' (e.g. the Attica prison riots of 19716and at Strangeways in 19807), but there are numerous forms of protest and resistance used by prisoners to communicate dissatisfaction with the prison administration or other agencies of government. For example, in France in 1967 the concept of 'counterveillance' or 'optical activism' emerged when prisoners would observe and report on conditions of detention and treatment - a reversal of the panopticon to the synopticon; from the few watching the many to the many watching the few.8Demonstrations and work stoppages are other examples of protest. Prisoners going on hunger strike are a peaceful means of communicating a particular message to the authorities and the public. The hunger strike of imprisoned Irish Republican Army (IRA) members in 1981 resulted in the death of ten prisoners9 and was preceded by the so-called 'Dirty Protest' during which protesting prisoners refused to slop out, only wore blankets and smeared cell walls with faeces.10 Prisoners may also refuse to return to their cells as was the case in June 2017 at Kgosi Mampuru prison in Pretoria11 or refusing to come out of their cells.12 Challenging language, being rude and swearing at officials are also forms of protest by prisoners. More extreme examples of protest include self-mutilation by prisoners,13 as was the case of some 1 300 Kyrgyz prisoners who sewed their mouths shut in 2012,14 and Ecuadorian awaiting trial prisoners crucifying themselves in 2003, protesting their unlawful detention.15

In view of these different terms, the term 'prisoner protests' will be used to depict the range of actions, individual and collective, that prisoners take to communicate their displeasure in a manner outside of the accepted procedures for conflict resolution dictated by prison law, regulations and Standing Orders. It should also be added that prisoner protests may be about something that has happened or is not happening for which the prison administration is responsible, but it may also be about something that the prison administration has no control over, as was the case in 1994 in South Africa with prisoners' participation in the election and expectations of an amnesty.

Building on the preceding, two broad issues can be discerned. The first is the scale of the protest with reference to the number of people involved, the extent of damage caused, the duration of the unrest, the extent of injuries and fatalities, the effort required to regain control, the wider impact on society and the necessity to implement reform. If the prison administration loses control, it is no longer able to meet its constitutional and statutory obligations. Whether the prison administration remains in control, or has lost control of a cell, a section of a prison or an entire prison is of course critically important, since it is fundamental to the operation of a well-managed prison that the administration is in control. A second broad issue is the aim of the protest with reference to the desired outcome, e.g. an individual's access to health care versus participation in a general election. There is thus a political dimension to it - it is a response borne out of a grievance of some nature. A protest may also be instigated by organised criminal elements within the prison, but this seems to be the exception rather than the rule. The Comando Vermelho (Red Command) of Rio de Janeiro has, however, on more than one occasion, orchestrated prison unrest in response to imprisonment policies.16

An uneasy peace, or not

Some prisons perform better than others - some are beset by violence and rights violations, whereas others seldom see conflict and allegations of ill treatment. In her extensive work on prisons and their moral performance, Liebling has established that fairness and legitimacy are critical to prison life with measurable impact on order in the prison.17 This conclusion has been further expanded by Liebling and colleagues using a 'prison quality' survey identifying values relating to interpersonal treatment: respect, humanity, fairness, order, safety, and staff-prisoner relationships.18 She notes:

What made one prison different from another was the manner in which prisoners were treated by staff, how safe the prison felt and how trust and power flowed through the institution. Prisoners' well-being was to a large extent a consequence of their perceived treatment. Prisons were more punishing and painful where staff were indifferent, punitive or lazy in the use of authority.19

What then appear to be the major determinants of prisoner well-being are responsive, approachable and respectful staff.20 How officials respond to complaints and requests from prisoners is central to prisoner well-being and ultimately to the overall level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction amongst prisoners. When prisoner complaints and requests are ignored or not dealt with properly, this can have dire consequences. A small qualitative South African study found support for the notion that being ignored is one of the most difficult experiences of imprisonment according to interviewed former prisoners:

After two weeks I got chicken pox and I went to the nurse but she said I must wait until next week because the doctor is now not here now. Being ignored is the worst. Some participants held very strong views on the nature of care received during imprisonment: You are not treated like a human being. The food is bad and you don't get medical treatment; they treat you like an animal. People die in front of us because they don't get help. When you lay complaints, it takes a long time to get a response.21

Dealing effectively and fairly with complaints are key to prison harmony or disruption. Under South African law, prisoners have a number of avenues open to them to lodge complaints. The internal complaints mechanism is provided for in s 21 of the Correctional Services Act (111 of 1998) and prisoners also have access to the Independent Correctional Centre Visitors (ICCV) of the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services (JICS) and to the Inspecting Judge as well.22 Prisoners can also direct complaints to the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC), and may also approach the courts.23 In 2019 South Africa ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) and JICS forms part of the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) with the SAHRC being the coordinating structure. The NPM is, however, not yet functional (May 2022) and does not constitute a distinct complaints mechanism. As a party to OPCAT, South African prisoners can be visited by the UN Sub-Committee on the Prevention of Torture (SPT), which may also receive complaints from prisoners but should not, for the present discussion, be regarded as a regular complaints mechanism.24

Even though the Correctional Services Act provides for a complaints and requests mechanism, it can safely be assumed that such an internal complaints mechanism will be constrained by its own reputation for effectiveness as well as the nature of the complaint. If a complaint concerns a member of the prison staff, or concerns a particularly sensitive or private matter it is less likely that the internal complaints mechanism will be used. The complaints mechanism can also be used for requests, such as a request to see a doctor or social worker who may be in a better position to deal with the substance of the complaint. On paper, there seems to be sufficient provision for avenues by which prisoners can lodge complaints. The following sections look at a number of prisoner protest incidents to get a sense of complaints and grievance handling and prisoner reactions. The annual reports of JICS report a large number of complaints of largely a repetitive nature. In the following section eight incidents of protest are described and analysed.

Eight incidents

The following provides brief descriptions of protest events in prisons between October 2011 and July 2017 that will be drawn on to further the analysis. The information was mostly obtained from JICS. That the events occurred some time ago is not regarded as an impediment to the analysis, as they are used as examples to get a better understanding of how protests develop, and are not the immediate subject of investigation here.

Case 1: Odi Correctional Centre, north west of Pretoria, Gauteng

In October 2011 at Odi Correctional Centre the cancellation of a planned family day sparked protests, made possible when six officials simultaneously unlocked 600 prisoners. Once unlocked, inmates chased officials out and barricaded entrances to the unit and set fire to mattresses. SAPS, Metro Police and the Fire Department were called. Rubber bullets were fired from the roof at inmates, and they retreated to the cells. They were locked up but unlocked again and assaulted. It was reported that 19 prisoners were assaulted; one was shot in the leg, and one official was assaulted. Some 24 shots were fired.

The JICS investigation found other sources of dissatisfaction as well, such as: officials were reportedly reluctant to provide escorts to school and hospital; poor quality of the food; there were excessive prices asked at the tuck shop; there was a shortage of bedding, cleaning materials and prisoner uniforms; and a lack of family contact due to the distance to the prison.

Case 2: Krugersdorp Correctional Centre, Western Gauteng

At Krugersdorp Correctional Centre in November 2011 an inmate with a diagnosed mental illness requested to be taken to the hospital to receive his medication. After his request had been refused for two days, he started a fire with sponges in the ablution area of the communal cell in which he sleeps. One inmate was treated for smoke inhalation. The prisoner had made previous attempts at suicide and was known to the Head of Centre (HoC). He had previously requested to see a psychologist. The prisoner had obvious mental health problems and the denial of access to his medication led to a heightened state of agitation.

Case 3: Grootvlei Correctional Centre, Bloemfontein, Free State

In November 2011, at Grootvlei Correctional Centre, awaiting trial prisoners expressed their unhappiness to the HoC, through a memorandum, about being awaiting trial for long periods, some as long as five years. Other allegations, including ill treatment by the police and racist attitudes by prosecutors, were also aired in the written complaint to the HoC. A meeting between inmates and representatives from relevant government departments was arranged, but the Regional Commissioner intervened and the meeting was cancelled. In protest, a section key was stolen from an official, but it was soon recovered. However, a riot broke out and detainees burnt the offices of unit managers at C and D units and the clinic at C unit was destroyed. The Emergency Support Team (EST) was called in and rubber bullets were fired. Two prisoners were shot in the head and one is reportedly paralysed. Exact injury numbers are unknown.

Case 4: Boksburg Correctional Centre, Gauteng

In May 2012, at Boksburg Medium A Correctional Centre, inmates were informed that the Area Commissioner made a decision that all electrical appliances (e.g. kettles) had to be removed from the cells. A meeting was held with staff and inmates to work out ways in which electrical appliances could be removed in an orderly manner and collected by families. The Regional Commissioner was present, but was not given an opportunity to address the meeting. Two days later a hunger strike commenced. The EST moved in to remove the electrical appliances and used tear gas. Seven inmates were injured.

Case 5: Groenpunt Correctional Centre, Deneysville, Free State

In January 2013, at Groenpunt Correctional Centre, a protest started following the cancellation of a soccer match. Inmates refused to go back to their cells after unlocking and began pelting officials with rocks. The EST was called in with full riot gear, and ultimately 101 prisoners were injured. The underlying reasons for the protest are well-documented and relate to the following:

• the Participative Management Committee (PMC) did not communicate decisions of a meeting on 30 November 2012 adequately to inmates;

• the Head of Centre did not deem complaints important enough to deal with immediately;

• the Area Commissioner did not visit the section personally to deal with complaints;

• the PMC encouraged inmates to riot and had rocks piled in the courtyard;

• the food was reportedly not good and milk regularly turned sour as the cold room was not working;

• medication was not dispensed on time;

• a shortage of nurses and limited access to health care was reported;

• serious injuries were not attended to;

• regular CD4 counts were not done for HIV+ prisoners;

• it was reportedly untrained officials who decided who will be allowed to seek medical attention;

• the food handlers' dress code and protective gear were inadequate;

• there were no social work services, developmental programmes or recreational programmes;

• the Case Management Committee did not conduct six-monthly consultations with inmates;

• there was dissatisfaction with the security reclassification tool;

• there were plumbing, electricity and general maintenance problems;

• maximum security inmates did not have access to social work programmes; and

• the Groenpunt Correctional Centre is remotely located and difficult to visit for families.

Case 6: St Alban's Correctional Centre,25Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape

On 26 December 2016 three prisoner died at St Alban's Correctional Centre. It is alleged that inmates from Cells 22 and 23 in B-Unit at St Alban's were denied privileges without being provided with the reasons. Prisoners belonging to both 26 and 28 number gangs planned and executed a coordinated attack, first targeting two officials. There were two scenes of attack, the first near the dining hall and the other near the records office, where officials stabbed inmates with knives. Three inmates died, 25 were injured, and fwe officials were stabbed.26

Case 7: Leeuwkop Correctional Centre, Johannesburg, Gauteng

From Leeuwkop Correctional Centre in December 2016 it was reported that it had been the practice for inmates to store their personal belongings in buckets. On 23 December a cell search was conducted and the buckets confiscated, as it was alleged that they were being used to brew beer. Inmates' property was also strewn about the cell in the course of the search. The inmates demanded a meeting with the HoC or Area Manager, as the acting HoC did not want to listen to their complaint about the buckets. They retreated to their cells and refused to come out for lunch. The EST was called in and tear gas was used. Someone started a Are. It is reported that an unknown number of inmates were hospitalised.

Case 8: Kgosi Mampuru II Correctional Centre, Pretoria, Gauteng

In July 2017, a group of prisoners at Kgosi Mampuru II Correctional Centre, serving life imprisonment, staged a sit-in, protesting that, following the Van Vuren judgment,27 their cases should be considered for parole and that this was not being done with a sense of urgency.28Attempts were made to get them to return to their cells but this failed and the EST was called in. Several inmates were injured but the exact number is unknown.29

Some observations

Even if the incident descriptions are not particularly detailed, a number of observations can be made to gain a better understanding of how events unfolded. The first issue to point out is that in some cases there was a perception that an event was cancelled unilaterally by the prison administration. From this it was evident that the cancelled event was regarded as valuable to the prisoners, i.e. family-day visits and a soccer match. It can be accepted that a sense of unfair punishment lies at the heart of these protests. The second cause of conflict was that something, a resource, that was regarded as useful, if not indispensable, was confiscated, or instruction was given for it to be confiscated, e.g. kettles and buckets. If reasons for the decision were communicated to the prisoners, these were rejected, or regarded as inadequate. A third issue is that prisoners sought access to a higher authority (e.g. the Regional Commissioner, Area Commissioner or other government departments) and this was denied, blocked or not enabled after the expectation was created that it would happen. Fourth, there was frustration with delays in decision-making concerning the cases of prisoners, whether that referred to criminal trials or amending sentences. Fifth, there seems to be a pattern that other underlying reasons preceded the incident and these cover a wide range of issues concerning treatment and conditions of detention and even the actions of public servants outside the Department of Correctional Services (DCS). Sixth, in a number of instances the EST was called in to respond to the protest and there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence that EST officials frequently engage in the excessive use of force.30

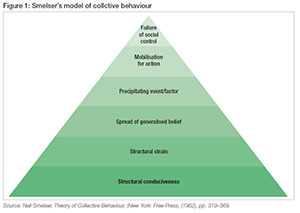

Against this backdrop, one may indeed call upon Smelser's model of collective behaviour to provide some guidance in understanding these protest actions - see Figure 1 below.31People behaving collectively, i.e. as a group in the form of a crowd, a riot, protests and social movements have been a long-term topic of investigation by sociologists and other social scientists. This particular field of study has its roots in the French Revolution and the perceived threat of the unruly and destructive crowd to the social order.32 Early theorists on collective behaviour placed much of the emphasis on 'the crowd' and the people that make up the crowd.33 Smelser's 1963 'Theory of collective behaviour' argued that for collective behaviour to occur, a series of structural features need to be in place. This he articulated as sequential value-adding stages, moving from the general to the increasingly specific, culminating in collective behaviour, such as a riot or protest.

The first requirement would be structural conduciveness for collective behaviour, such as a protest. This refers to the broad social conditions that are necessary for an episode of collective behaviour to occur, for example being detained in a prison where there is a clear hierarchy. The second requirement is structural strain, which exists where various aspects of a system are in some way 'out of joint' with each other. This can be an experience of social dissatisfaction and disgruntlement. The third requirement is the growth and spread of a generalised belief that something or someone is responsible for their state of dissatisfaction and disgruntlement. This generalised belief provides a diagnosis of the forces and agents that cause the strain, and also articulates a response for coping with the strain. An example is a general belief that prisoners are being treated unfairly by the current prison administration, as complaints are not being dealt with and feed-back not provided. A response could then be from prisoners that their concerns are trivialised, or not recognised. The fourth requirement is that there are precipitating factors or an event that triggers the response. Something happens that creates, sharpens and exaggerates other factors. This event provides the 'concrete evidence' of the wrongness of the administration. The next step is the mobilisation of participants for action. A decision is taken collectively, or by an individual or a leadership group to mobilise for action. This can take the form of a sit-in, or blocking of the cell door and so forth. The next and final step is the re-assertion of social control. In a prison setting this typically takes the form of riot control, or interventions using force and coercion. However, it would be an equally valid, if not a more desirable response, to take measures to de-escalate the situation and avoid the use of force.

Given the above description of prison protests from a largely sociological perspective, the focus will now shift to a rights perspective and the South African legal context is, indeed, accommodating of prisoners' rights.

The right to protest

Section 16 of the Constitution protects the right to freedom of expression and s 17 gives all 'the right, peacefully and unarmed, to assemble, to demonstrate, to picket and to present petitions.' That prisoners remain part of the political process has also been confirmed in two Constitutional Court decisions, with reference to the right to vote.34 The principle that prisoners retain all their rights save for those necessary to implement the order of the court was indeed established in a 1912 decision by the then Appellate Division and later reaffirmed in Minister of Justice v Hofmeyr:35

Mr Esselen contended that the plaintiffs, once in prison, could claim only such rights as the Ordinance and the regulations conferred. But the directly opposite view is surely the correct one. They were entitled to all their personal rights and personal dignity not temporarily taken away by law, or necessarily inconsistent with the circumstances in which they had been placed. They could claim immunity from punishment in the shape of illegal treatment, or in the guise of infringement of their liberty not warranted by the regulations or necessitated for purposes of gaol discipline and administration.36

Sections 16 and 17 of the Constitution, read together with the case law cited, make it clear that prisoners are not, merely because they are prisoners, excluded from the right to protest. However, as can be anticipated, prison managers will be quick to point out that protests inside a prison will pose a threat to order and security and they may be right under certain circumstances. The Correctional Services Act also stipulates that it is a disciplinary infringement for a prisoner to create or participate in a disturbance or foment a mutiny or to engage in any other activity that is likely to jeopardise the security or order of a correctional centre or to attempts to do so.37 At issue is not the condonation of violent disruptive protests resulting in a real threat or actual harm and damage, but rather the right to peaceful demonstration as a collective. Admittedly the prison context is different from free society - confined spaces, a highly unequal power relationship and a population that may be prone to violence and destruction if their concerns are not addressed in a procedurally and substantively fair manner.

In free society protests are regulated by the Regulation of Gatherings Act (205 of 1993), but this legislation does not so easily accommodate prisons in its definitions and enforcement. For example, a gathering is defined as 'any assembly, concourse or procession of more than 15 persons in or on any public road as defined in the Road Traffic Act (29 of 1989), or any other public place or premises wholly or partly open to the air'.38 Section 5 of the Act also provides for the banning of assemblies and demonstrations if they pose and imminent and direct threat to public security.39

From the above it is evident that the drafters of the Regulation of Gatherings Act did not consider a prison setting as a place of protest as allowed for in the Constitution and otherwise enabled in free society by the Regulation of Gatherings Act. The particular context envisaged is a community setting, noting the role of South African Police Service (SAPS) and traffic officers, and reference is also made to the community police forum. Moreover, permission for a protest is sought from the relevant local authority - an arm of government that holds no power over the national competency of Correctional Services.40

The Correctional Services Act, Regulations and B-Orders (the standing orders) are also not helpful in setting out how prisoners can exercise their rights under ss 16 and 17 of the Constitution. The emphasis is rather placed on dealing with complaints and requests in a proactive manner and the B-Orders are instructive:

One of the elements whereby a calm and satisfied prison population can be accomplished is the existence of a well-established and effective complaint and request procedure. The afore-mentioned procedure must be an accessible, efficient and credible system by means of which prisoners can air their complaints and grievances in order to:

• create an acceptable prison environment;

• ensure the efficient management of prisons;

• to avoid the build-up of frustration and together with that unacceptable and/ or destructive behaviour such as gang activities, uprisings, hunger strikes, the writing of illegal letters of complaint and assaults;

• ensure control over the requests by writing down the complaints and the requests, and

• ensure proper recordkeeping in the interest of both officials and prisoners.41

A closer reading of the B-Orders also indicates that complaints must be individualised and that complainants should not be dealt with in groups: 'The complaints of prisoners must not be heard in a group because it can lead to complaints of the same nature without any substance.'42 It is this very requirement that removes the powerful symbolism of collective action which free citizens can exercise.

The B-Orders also deal with hunger strikes by prisoners, but the provisions are also lopsided in favour of the authorities. If a prisoner is dissatisfied with one or more issues and decides to embark on a hunger strike, the officials must take careful note of the complaint and deal with it in a prompt and effective manner to ensure its speedy resolution. If, in the view of the authorities, the reason for the complaint has been addressed, but the prisoner continues with the hunger strike, then the prisoner will be subject to disciplinary action because 'hunger striking is regarded as a serious transgression of the prison disciplinary system'.43 Despite the prohibition of hunger striking in the B-Orders, there is no specific empowering provision concerning hunger striking in the Correctional Services Act where it provides for the making of regulations and standing orders by the Minister.44Chapter 15 of the Correctional Services Act also lists offences by prisoners and hunger striking is not included there either.

Prisoners, with reference to the right to free speech and the right to peaceful demonstration, find themselves in a situation where they can claim these rights, but the enabling legislation is not only lacking, but there are strong indications that the operational procedures prevent them from exercising these rights. There seems to be the view from DCS that any form of protest is regarded as a threat to the good order of the establishment as well as the life and limb of all concerned. From this position a forceful response becomes readily justifiable. However, the cases highlighted that, if they are taken on face value, questions can be raised about compliance with use of minimum force requirements.

Conclusion

Protest actions in South African prisons are not entirely uncommon, but large-scale, highly disruptive protests, where the DCS loses control of a prison for a prolonged period has not occurred in recent years. What seem to be more common are smaller scale and issue-specific protest actions by prisoners. Two broad issues stand out from this brief review of incidents and the legal framework.

The first is the underlying reason, which appears in many instances to point to procedural fairness: for example, when something that has value for the prisoners is removed by the prison administration in a unilateral fashion, or reasons are not properly communicated. It also relates to procedural fairness by the courts when trials are delayed, or changes to how sentences should be calculated, which flow from decisions of the courts, are not implemented promptly. These deficits in procedural fairness are important drivers of prisoner discontent. It is not only the original cause of discontent that is the problem, but also how the Department responds to such discontent. The explicit aim must be to reduce the potential for conflict through effective complaints and grievance handling. That means that the reasons for decisions (and delays) must, at a minimum, be properly communicated to those affected.

Second, while the Constitution recognises the right to protest, the Correctional Services Act, Regulations and B-Orders do not enable the exercising of the right, but, through omissions, facilitate, if not encourage, a forceful and intolerant reaction from DCS to frustrated complainants and the grievances they raise.

Prisoner protests and violent responses thereto are not new, and they have persisted since 1994. The systemic issue appears to be the efficacy of complaints handling and dealing with grievances in a manner that is transparent and accountable, and reduces the risk for conflict and tension. It should be remembered, above all, that the administration has the upper hand in law and practice. This means that it has options open to it to select from in dealing with tension and conflict, and reduce the need to use force. The prison administration is not, like a train, on a track of predetermined inevitabilities. On the contrary, the prison administration is invited by the Constitution to take a dynamic approach and maintain an open mind to promote and protect the right to dignity and, flowing therefrom, the right to bodily integrity and freedom from torture and other ill treatment.

Notes

1 Lukas Muntingh is Project Coordinator of Africa Criminal Justice Reform (ACJR). He holds a PhD (Law) from UWC and an MA (Sociology) from Stellenbosch University. He has been involved in criminal justice reform since 1992. He has worked in Southern and East Africa on child justice, prisoners' rights, preventing corruption in the prison system, the prevention and combating of torture, and monitoring legislative compliance. He has published extensively and presented at several conferences. His current focus is on the prevention and combating of torture and ill-treatment of people deprived of their liberty.

2 Farhana Haider, "Protests at Chile Fire Prison", BBC News, 11 December 2010, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-latin-america-11977402.

3 Johann Kriegler, Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Unrest in Prisons (Pretoria: The Commission, 1995), 26. [ Links ]

4 Ibid, 20.

5 Lukas Muntingh, Reducing Prison Violence: Implications from the Literature for South Africa (Bellville: CSPRI Research Report 17, Community Law Centre, 2009). [ Links ]

6 Bert Useem and Peter Kimball, "A Theory of Prison Riots", Theory & Society 16, no. 1 (1987): 87-122, https://www.jstor.org/stable/657079. [ Links ]

7 Eric Allison, "The Strangeways Riot: 20 Years On", The Guardian, 30 March 2010, http://www.theguardian.com/society/2010/mar/31/strangeways-riot-20-years-on. [ Links ]

8 Michael Welch, "Counterveillance: How Foucault and the Groupe d'Information Sur Les Prisons Reversed the Optics", Theoretical Criminology 15, no. 3 (2011): 301-13, DOI: 10.1177/1362480610396651. [ Links ]

9 Naoki Kanaboshi, "Prison Inmates' Right to Hunger Strike: Its Use and Its Limits under the U.S. Constitution", Crimina Justice Review 39, no. 2 (2014): 121-139, DOI: 10.1177%2F0734016814529964. [ Links ]

10 BBC History, "'Blanket' and 'No-Wash' Protests in the Maze Prison", BBC - History Website, 24 May 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/events/blanket_no-wash_protests_maze. [ Links ]

11 News24, "Kgosi Mampuru II Warder and Prisoner Injured during Riot", News24, 3 June 2017, https://www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/News/kgosi-mampuru-ii-warder-and-prisoner-injured-during-riot-20170703. [ Links ]

12 News24, "Klerksdorp Prisoners Go on Hunger Strike", IOL, 26 August 2021, https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/klerksdorp-prisoners-go-on-hunger-strike-320019. [ Links ]

13 Pedro Olmo, "The Corporal Repertoire of Prison Protests in Spain and Latin America - the Political Language of Self-Mutilation by Common Prisoners", The Open Journa of Socio-Political Studies 9, no. 2 (2016): 666-690. [ Links ]

14 "More Than 1,300 Kyrgyz Prisoners Have Sewn Their Lips Shut in Protest", Business Insider, 25 January 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-16722757.

15 Chris Garces, "The Cross Politics of Ecuador's Penal State", Cultural Anthropology 25, no. 3 (2010): 459-96, 459, DOI: 10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01067.x [ Links ]

16 Benjamin Lessing, Inside-out: The Challenge of Prison-based Criminal Organisations (Washington: Brookings, 2016), 13.

17 Alison Liebling, "Moral Performance, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment and Prison Pain". Punishment and Society 13, no. 5 (2011): 530-550, 535, DOI: 10.1177/1462474511422159. [ Links ]

18 Ibid, 535.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Lukas Muntingh, Ex- prisoners' Views on Imprisonment and Re-Entry (Bellville: Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative, 2009), 10.

22 Correctional Services Act (111 of 1998), Chapters 9-10.

23 Minister of Home Affairs v NICRO (CCT 03/04) [2004] ZACC 10; 2005 (3) SA 280 (CC) (3 March 2004); Van Vuren v Minister of Correctional Services and Others (CCT 07/10) [2010] ZACC 17 (30 September 2010); Appollis v Correctional Supervision and Parole Review Board and Others CA171/09) [2010] ZAECGHC (14 January 2010); Derby-Lewis v Minister of Correctional Services and Others (54507/08) [2009] ZAGPPHC 7 (17 March 2009); Lebotsa and Another v Minister of Correctional Services and Others (6478/2009) [2009] ZAGPPHC 126 (29 October 2009); Phaahla v Minister of Justice and Correctional Services and Another (97569/15) [2017] ZAGPPHC 617 (3 October 2017); Thkwane and Others v Minister of Correctional Services and Others (16304/2004) [2005] ZAGPHC 220 (21 April 2005); Stanfield v Minister of Correctional Services and Others [2003] ZAWCHC 46 (12 September 2003); Walus v Minister of Correctional Services and Others (41828/2015) [2016] ZAGPPHC 103 (10 March 2016); Qaqa v Minister of Correctional Services and Another (83547/2016) [2017] ZAGPPHC 917 (4 July 2017).

24 United Nations, Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Treaty Series, vol. 2375, 237, Parts II-III.

25 "Overcrowding, Staff Shortages Fuelled Fatal St Albans Prison Riot: Cope", TimesLIVE. 29 December 2016, https://www.timeslive.co.za/politics/2016-12-29-overcrowding-staff-shortages-fuelled-fatal-st-albans-prison-riot-cope/.

26 Department of Correctional Services, "Correctional Services on death of inmates at St Albans Correctional Centre", Press Release, 27 December 2016, https://www.gov.za/speeches/three-inmates-die-after-assault-official-st-albans-correctional-centre-27-dec-2016-0000.

27 Van Vuren v Minister of Correctional Services and Others (CCT 07/10) [2010] ZACC 17; 2010 (12) BCLR 1233 (CC); 2012 (1) SACR 103 (CC) (30 September 2010).

28 The essence of the Van Vuren judgment was that the minimum non-parole period for life imprisonment applicable to the applicant was confirmed by the Constitutional Court to be 15 years and not 20 years, as was introduced by a new policy at the time.

29 Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services, "Kgosi Mampuru II Warder and Prisoner Injured during Riot"; Office of the Inspecting Judge, Annual Report of the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctiona Services 2017/18 (Pretoria: Office of the Inspecting Judge, 2018), 42.

30 Sisonke Mlamla, "Inmates Complain about the Excessive Use of Force by Prison Officials", IOL, 21 May 2021, https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/inmates-complain-about-the-excessive-use-of-force-by-prison-officials-29182900-96b5-4451-a7cc-82966d7e4a5c; "Most Allegations of Assault in Prison Are Not Properly Investigated", GroundUp News, 22 June 2017, https://www.groundup.org.za/article/most-allegations-assault-prison-are-not-properly-investigated/.

31 Neil Smelser, Theory of Collective Behaviour (New York: Free Press, 1962).

32 Gustave le Bon, The crowd: A study of the popular mind. (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1960).

33 Ralph Turner and Lewis Killian, Collective behaviour (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1957).

34 August and Another v Electoral Commission and Others (CCT8/99) [1999] ZACC 3 (1 April 1999); Minister of Home Affairs v NICRO.

35 Minister of Justice v Hofmeyr No. (240/91) [1993] ZASCA 40 (26 March 1993).

36 Whittaker and Morant v Roos and Bateman AD 92 (1912).

37 Correctional Services Act 1998, subsecs 20(1)(o) and (t).

38 Regulation of Gatherings Act (205 of 1993), see Definitions.

39 Regulation of Gatherings Act 1993, s 5(1); Ian Currie and Johan de Waal, The Bill of Rights Handbook, 5 ed. (Juta: Cape Town, 2005) 411.

40 Regulation of Gatherings Act 1993, s 2(4)(a-b).

41 Department of Correctional Services, B-Order 1 -Incarceration Administration, chap. 22, para 1.1.

42 Department of Correctional Services, B-Orders, pts 1, chap. 22, para 3.1(b).

43 Department of Correctional Services, B-Orders, pts 1, chap. 13, para 4.2.1(d). If the prisoner still indicates that he/she is persisting with his/her hunger strike after all the above-mentioned actions have been taken, the Case Management Committee must listen to his/her reasons/motivation for persisting in his/her hunger strike. If the Case Management Committee is convinced that all his/her complaints/problems were dealt with effectively, it must be pointed out to the prisoner that hunger striking is regarded as a serious transgression of the prison disciplinary system and that the following steps will be taken against him/her in terms of Section 24(3)(4) and (5) of the Correctional Services Act.

44 Section 134(1) and (2) of the Correctional Services Act.