Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.69 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2020/i69a8351

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Poaching of marine living resources: Can the tide be turned?

Hendrik van As1

ABSTRACT

Certain marine living resources of South Africa are under severe threat from international organised crime syndicates in conjunction with local fishers. These criminal activities erode respect for the rule of law and lead to socio-economic degradation and the proliferation of gangsterism. The current government approach as custodians of the resources is to maximise the return from confiscations. SAPS are not using the full power of the law to address poaching of marine living resources, particularly abalone, as a priority crime and do not allocate their resources commensurate with the value of the commodity. As a country that is beleaguered by fisheries crime, overfishing and exploitation, South Africa must take a tough stance and should pursue criminal organisations with all the power that the state can muster. It must also ensure that national fisheries resource management is improved so that local communities can benefit. The implementation of a conforming strategy would be socially and politically unpopular, but the future benefits will outweigh the outlay.

Introduction

Two of South Africa's high-value marine living resources, abalone (Haliotis midae) and West Coast rock lobster (Jasus lalandii) are under threat of illegal harvesting and trade by organised criminal syndicates.2 In Paternoster, a village on the West Coast, visitors are overwhelmed by the audacity with which illegally harvested lobsters are offered for sale.3 Elandsbaai, north of Paternoster, is a well-known 'hotspot' for the smuggling of these crustaceans.4 Further to the south and east, abalone poachers enter the water undisturbed, in broad daylight and full view of the public.5 Levels of poaching have been described as 'epidemic'.6

Public outcries7 regularly result in special operations, but soon after their conclusion 'business is back to normal'.8 The perpetrators' activities have been described as 'the widespread plunder from our coastal waters.'9

The reasons that local communities become involved in poaching and their link to organised syndicates are well-documented.10 They include the marginalisation of certain communities because of apartheid policies,11 the failure of the state, the development of parallel sources of authority,12 corruption, poor fisheries management,13 pressure by family,14 greed,15drug dependency amongst harvesters,16and the exclusion of traditional fishers from the fisheries reform process, 'resulting in them operating outside the formal fishery management system'.17 Raemaekers and Britz also identified government's failure to issue fishing rights and to conduct effective sea-based compliance as contributing factors.18

These criminal activities erode respect for the rule of law, threaten sustainable livelihoods, and cause socio-economic degradation, the proliferation of gangsterism and increased associations with international criminal syndicates.19 The 'continuing breakdown in the rule of law, uncontrolled corruption and the collapse of public service delivery without holding culprits accountable' has led to the formation of parallel 'states' beyond the control of government.20

In many instances, poaching is carried out in an organised manner.21 It is often linked to other transnational crimes such as drug22 and human trafficking, weapons and cigarette smuggling, fraud, rhino poaching,23 as well as tax and customs evasion.24 According to De Greeff and Raemaekers, Chinese gangs were key to organising the illegal trade of abalone when its value increased. They linked up with established gangs and traded drugs for abalone.25 The protection afforded to the resources should be commensurate with the effort put into their theft.

This article illustrates the value of marine living resources as national assets and sets out South Africa's international and national obligations to ensure the sustainable use of selected resources, namely abalone and West Coast rock lobster. It describes the criminal threats to which the resources are exposed, identifies the government custodians entrusted to protect them, analyses the efficacy of current approaches to address inshore poaching, and finally, proposes alternative strategies to address poaching.

Marine resources as national resources

Natural resources are national assets that may be exploited, but they must be protected.26The fisheries industry employs many people and as such is a major contributor to household income.27 Fisheries are crucial for enhancing economic growth and poverty reduction. A substantial number of South African communities also depend on artisanal, subsistence or small-scale fishing.28

In 2018/19, there were 623 lobster catch right holders in the local commercial sector and approximately 2000 small-scale fishers who were not right holders, but who received annual permits. These numbers excluded recreational fishers who could also apply for permits,29coastal communities recognised as fishing communities30 and those with a customary right to fishing.31 The contribution of fisheries to the South African economy (GDP) was approximately USD 323 million in 2008 and the sector employed approximately 27 000 people.32

The utilisation, conservation, protection, preservation and management of marine resources are governed by the Marine Living Resources Act (MLRA).33 The Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) is tasked with the management and protection of the resources in terms of this Act.34

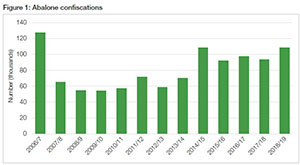

However, the collapse of abalone and West Coast rock lobster is looming.35 According to TRAFFIC, if the poached abalone were traded legally, it would have added R628 million per year to the economy.36 At a conservative value of R250 p/kg, the lobster confiscated in the period 2006-2019 (see Figure 1) amounts to R265 million. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) describes West Coast rock lobster as 'relatively stable but under considerable exploitation pressure' from commercial, recreational, and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and the abalone stock as 'severely threatened' with the 'stock at <5 percent of pristine estimates.'37 The total allowable catch for West Coast Rock lobster for the 2020/21 season was reduced by 22% and the number of fishing days have also been restricted. The responsible minister advanced the 'depleted status of the resource' as one of the reasons.38

International duty to protect MLRs

The extent and consequences of illegal fishing have long been recognised by the international community. International regulation started with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).39 UNCLOS identifies the need to 'promote the peaceful uses of the seas and oceans, the equitable and efficient utilisation of their resources, the conservation of their living resources, and the study, protection and preservation of the marine environment.'40

Part V of UNCLOS obliges coastal states to ensure, through proper conservation and management measures, that the maintenance of the living resources in its exclusive economic zone is not endangered by over-exploitation.41

The purpose is to maintain or restore harvested species at levels that can produce the maximum sustainable yield.42 South Africa has ratified and is bound by the UNCLOS, which makes it an international obligation to protect the resources against illegal activities.

Poaching is recognised as a major contributor to the depletion of certain marine resources.43 The FAO describes IUU fishing as 'one of the greatest threats to marine ecosystems due to its potent ability to undermine national and regional efforts to manage fisheries sustainably'.44 To curb this problem, several other international instruments have been adopted.45

The global community, including the FAO and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), has identified over-exploitation of MLRs as a threat to livelihoods and food security,46 particularly for developing countries.47Illegal harvesting takes advantage of weak management and enforcement regimes, especially those of coastal developing countries, predominantly located on the African continent.48

In 2015 all the United Nations Member States adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The SDGs 'are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere.'49 Goal 14 of the SDGs is to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources. Other relevant SDGs include Goals 1, 2, 8 and 16 that relate to ending poverty, zero hunger, decent work and economic growth, and peace, justice and strong institutions respectively. The SDGs are not legally binding, but countries are expected to work and report on progress towards their achievement.50

National imperative

Apart from the international obligations, the Constitution also gives everyone the right to have the environment protected through reasonable legislative and other measures that also promote conservation.51 Legislative measures that aim to give effect to this right are the MLRA and the regulations promulgated in terms the Act.52

The objectives of the MLRA include that marine living resources must be conserved for present and future generations53 and that compliance with international agreements or any applicable rules of international law is imperative.54The Act provides for the appointment55 and powers56 of fisheries control officers, who are tasked with protecting the resources, mostly by employing techniques of monitoring, control and surveillance.

Threats to the resources

The MLRA creates three categories of exploiters of abalone and lobster resources. These are subsistence, recreational and commercial fisheries.57 Subsistence fishers can harvest for personal consumption and excesses may be sold, albeit not on a commercial scale. Recreational fishing requires permits and is limited by season.58 Commercial fishing is formally governed and subject to the allowable commercial catch or total applied effort, or parts of both.59 There is, however, a fourth category that constitutes a separate informal industry: the people who illegally exploit resources for supplying the black market.60

In South Africa in 2015, an estimated 1 475 tons of West Coast rock lobster was poached.61Between 2008 and 2019, 370 742 lobsters were confiscated. These statistics do not include the fisheries stations of Cape Town, which did not submit reports, and Hout Bay, where all the records were destroyed in a fire.

Between 2006 and 2019, a total of 1 059 217 kilogrammes of abalone were confiscated and figure 1 below illustrates an upward trend.

TRAFFIC estimates that 96 million abalone units were poached in the period 2006 to 2016.62The quantities of illegally harvested abalone far exceed the legally produced varieties,63resulting in the notion that this crime is very often committed by highly organised criminal groups.64

In one of the earliest fisheries crime cases in South Africa's democratic era, crates were filled with abalone and labelled 'super kingklip' or 'kingklip fillets'.65 These were shipped to Hong Kong where they fuelled the demand for abalone. The case shows that illegal trade networks between South Africa and the Far East date back to at least the 1980s.

The connection between organised crime and abalone poaching was highlighted again in S v Roberts.66For a prosecution under the Prevention of Organised Crime Act67 (POCA) the state had to prove that an enterprise existed, that it participated in a pattern of racketeering activity, and that the accused could be directly connected to the enterprise. To prove this, investigating officers were granted permission to monitor the accused's cellular transmissions,68on the grounds that it is exceptionally difficult to gather evidence within Chinese organised crime syndicates, such as those connected to abalone poaching. The court found that both the directive and the evidence gathered were valid and admissible.

The Bengis-case illustrates the spectrum of criminal activities within the West Coast rock lobster commercial Ashing sector.69 Crimes ranged from underreported catches, bribed fisheries inspectors and the submission of false information to DEFF, to the smuggling of undocumented workers from Cape Town to work for low wages in a US processing plant.70The accused were charged under US and South African law.71

The accused were charged with smuggling in violation of US laws as well as violations of the Lacey Act.72 One key point from this case is the liberty with which white collar criminals, who engage in organised crime in the fisheries sector, operate. This is reflected in the comments of Bengis,73 that moved the Judge to remark:

I view his behavior [sic.] as evidencing an astonishing display of the arrogance of wealth and power. For example ... when asked by his associates about the possibility of being caught in this scheme,

Mr Bengis responded that he was unlikely to be prosecuted because he has, I quote, 'fuck you money'.74

A 2005 UN report on crime in Africa concluded that 'Africa may have become the continent most targeted by organised crime'.75 The link between IUU Ashing and transnational organised crime is well-established,76 and recognised as a threat to Africa by the African Integrated Maritime

Strategy (AIMS).

Many reasons have been advanced for the dramatic increase in illegal harvesting, including a steep increase in abalone prices in the 1990s. This, coupled with the low cost of harvesting, ease of access and a readily available workforce embedded in local communities, created ideal conditions for poaching. By 2005, between 1 000 and 2 000 tonnes of abalone, with an export value of USD 35-70 million per year, were harvested illegally in the Eastern Cape.77

The impunity with which illegal harvesting takes place illustrates the moral norms that developed in Ashing communities. There is little regard for the risk of severe sanctions and law enforcement has little deterrent effect. These attitudes are fuelled by feelings of entitlement over the resource, protest against existing rules and resistance against a fisheries management system that resulted in poverty and exclusion.78

Threats to MLRs can also come from within government. Corruption has plagued DEFF for years.79 Early in 2018, eight fisheries officials based in Gansbaai were arrested for corruption. It was alleged that they had used their positions 'to run one of the biggest abalone poaching syndicates in the Western Cape'.80 In November of that year, South Africa's fisheries authority was described as being 'in a state of crisis, paralysed by a factional war between its two most senior officials and hollowed out by a culture of corruption'.81 Poaching is enabled by corruption, which is especially rife within the abalone trade.82It is an obstacle to law enforcement efforts.

There have been several attempts by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) and the Secretariat for the Southern African Regional Police Chiefs Cooperation Organisation to fight these criminal syndicates.83 This included the Enhancing Regional Responses against Organised Crime project.84 Despite these efforts and special operations by Operation Phakisa, abalone and lobster poaching syndicates have grown and remain entrenched, posing one of the highest risks to South Africa's marine living resources. The total disregard for the rule of law and the contempt for law enforcement officers has been described as 'large-scale predatory behaviour'.85

Mandate to protect

The Chief Directorate: Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) of DEFF is primarily responsible for compliance and enforcement along South Africa's vast coastline and in its national waters. It draws its mandate from the MLRA86 and the regulations promulgated in terms of the Act.87 Its primary function is to ensure sustainable utilisation and protection of marine living resources.88 Because MCS's capabilities to ensure compliance and enforce the law are limited, the involvement of other government departments and law enforcement agencies is crucial to augment existing resources.89 The Chief-Directorate has 228 employees deployed in three directorates, namely Compliance,90 Monitoring and Surveillance,91 and Fisheries Protection Vessels.92 The South African Police Service (SAPS)93 is also mandated to protect marine living resources.94

Government approach to poaching

The general approach of the government as the custodian of marine living resources is a fisheries management approach. Fines for poaching are issued and, in the case of abalone, profits are maximised to achieve the highest return from confiscations.95 Up to a third of the department's operating budget is generated through the sale of confiscated abalone on the open market.96 The revenue generated by this 'legal' trade in abalone therefore corresponds directly to the efforts that go into enforcement.97 Successes are measured in terms of confiscation and arrests, resulting in a focus on detection rather than prevention.98

SAPS has been slow to consider the poaching of MLRs as a priority crime.99 It followed a typical Sherlock Holmes approach: once the culprit is found, the case is considered solved and the perpetrator is either charged with the illegal possession of abalone or crayfish or a fine is imposed. The possibility of linkages to organised criminal syndicates is only investigated in a limited number of cases. A prosecutor involved in a number of marine-related cases prosecuted in terms of POCA explained that 'law enforcement agencies are slow and reluctant to employ the tools provided in the Act for the combatting of organised crime'.100 The first reference to abalone in the annual reports of the SAPS is found in 2017/18, which notes that 'dealing in abalone' is a national priority offence.101 By that time the involvement of international syndicates was well known.

Special operations are occasionally launched against poaching. Crookes showed that poaching decreases during periods of heightened law enforcement, but that it returns to pre-operation levels quite quickly.102 Poaching activities in the targeted area may decline, but poachers temporarily move to areas where there is less law enforcement focus. Special operations against abalone poaching in the Overstrand area resulted in increased rock lobster poaching on the West Coast and increased illegal abalone activity in the Southern and Eastern Cape. During one such operation, 48 poachers from the Gansbaai area were arrested in the Southern Cape with 142 kg of abalone.103 Poaching in the Table Mountain National Park doubled after such an operation. The increase in poaching was linked directly to the closure of the recreational fishery: denying recreational or subsistence fishers access to resources contributed to illegal fishing.104

In 1968, Becker argued that the number of offences that are committed is the result of the probability of conviction per offence, and the punishment per offence.105 The South African authorities restrict access to abalone106 and West Coast rock lobster primarily through monitoring, control and surveillance, arresting offenders, and imposing penalties (usually an admission of guilt fine). Often these fines are seen as acceptable risks given the lucrative value of the trade.

The probability that a perpetrator will be detected, convicted and appropriately punished is slim. This leads to an increase in the supply of offences.107 The culprits who are apprehended tend to be disadvantaged people, working for syndicates or criminalised because of their poverty. Arresting these offenders does not disrupt supply chains or deter the ringleaders who are seldom pursued. lives to steal another day. When an investigator in a coastal city sought assistance from a senior officer in Gauteng, where the kingpin was located, he was told that it is not a priority in Gauteng as 'we don't have a sea here'.108

Other role-players in the criminal justice system contribute to the state of affairs. In some instances, it takes up to 20 years for cases to be finalised. A case that originated in the early 2000s, for example, was finalised in 2019.109Easy access to bail also leads to repeat offences. For example, Elizette Marx who was first arrested in November 2002 on charges of racketeering, was arrested again following year, whilst on bail, when she planned a raid on a Worcester warehouse full of abalone.110

The number of fisheries cases brought in terms of POCA are minimal. The principal reasons for this are that FCOs have neither the mandate nor the capacity to undertake complex investigations. SAPS is also not geared towards POCA-style investigations, notwithstanding an initiative launched by the NPA after POCA came into operation. Law enforcement agencies are slow and reluctant to employ the tools provided for the combatting of organised crime in the POCA.111 Poaching has not been seen as a priority crime,112 allowing criminal organisations to entrench themselves.

Conclusion and recommendations

The agencies intended to regulate and monitor the sustainable capture of marine living resources are not achieving success.113 Wild abalone resources in South Africa have been 'decimated by poaching along the South African coastline, while national management and international co-operation have been inadequate in controlling ... illegal fishing'.114 This is largely due to legislation and regulations that were drafted without adequate consultation with coastal communities115 and policies that criminalised large parts of the community by excluding local populations from accessing resources.116

The failures in fisheries management, the allocation of insufficient resources, and the entrenchment of corruption117 and maladministration118 has led to a situation where fisheries crime has become entrenched. The illegal harvesting of MLRs has been 'legitimised' and normalised within some communities.119The widely accepted 'attitudes to compliance' pyramid, which shows most people are willing to obey the law if government makes it easy to obey the law, no longer holds true for South Africa. The opposite is closer to the truth. As is illustrated in figure 2, large parts of coastal communities either decided not to comply or will comply if they know the authorities are preparing to act against perpetrators.

SAPS and the NPA, key players in the prosecution of fisheries crime, also lack understanding of the situation. A person found with half a bag of abalone is not harvesting for personal use or even for trade, but is part of a bigger, organised set-up that should be fully investigated and prosecuted as such. Hauck describes it as 'a poaching hierarchy that begin with those at the water's edge and ends with highly organised Chinese Triads'121 that have been involved in illicit activities in South Africa since the 1970s.122

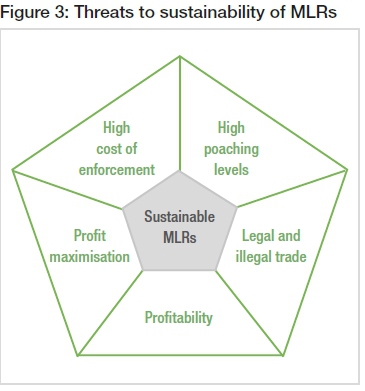

The long-term maintenance of lobster and abalone is uncertain and their future sustainability as economic resources is under extreme pressure. Crookes identifies five fatal threats to sustainability as illustrated in figure 4. All of these are present in respect of lobster and abalone.123

The bulwarks of the pentagon can only be dismantled if at least one of the walls is breached. South African poaching is not a linear process.124 Local residents may be the most active participants, but these transactions most often ultimately involve organised criminals. Police must therefore target the link between the poachers and the syndicates by using POCA.

Organised large-scale poaching of MLRs threatens the rule of law and the sovereignty of the State. This requires South Africa to take a tough stance and to pursue criminal organisations with the full force of the law and all the power that it can muster. At the same time, it must ensure that national fisheries resource management is extensively improved. A similar approach worked in Indonesia.125

The implementation of a strategy aimed at improving complaince will be socially and politically unpopular. The costs will be high and the strain will be felt in the present, but the future benefits will outweigh the costs.126Sumaila et al found that, from an economic perspective, it would take just twelve years to start reaping the benefits.127 To kickstart recovery of the fisheries resource, substantial short-term reduction of the total allowable catch and a sharp increase in measures to address IUU fishing and fisheries related crime are required.128 Culprits should be made to understand that crime does not pay.

Notes

Hennie van As: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5288-5344.

1 Hennie Van As is a Professor in the Department of Public Law and Director of the FishFORCE Academy at Nelson Mandela University, One Ocean Hub Co-investigator with funding from the United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) (Grant Ref: NE/S008950/1) and Honorary Senior Fellow in the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS) at the University of Wollongong, Australia.

2 Figures 1 and 2. L Berry, G Curtis, S Elan et al, Transnational activities of Chinese crime organizations, Library of Congress, 2003, 35. Also see United States v. Bengis, 631 F.3d 33, 35, 88 CrL 518, 2d3Cir. (2011) WL 2922292, 2013 and J Glazewski, Current legal developments South Africa/ United States. United States v Bengis: a victory for wildlife law and lessons for international fisheries crime, Internationa Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 29: 1, 2014, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ljmc29&i=179.

3 Personal experience in April 2018 and September 2020.

4 Interview with a senior fisheries control officer on 6 October 2020 in Langebaan.

5 Personal observations in June 2020.

6 Defenceweb, Abalone poaching at epidemic levels, 28 September 2018, www.defenceweb.co.za/security/border-security/abalone-poaching-at-epidemic-levels/ (accessed 20 October 2020).

7 Reports are often carried in local newspapers where communities are affected by the behaviour of poachers. Examples include the Hermanus Times, Kouga Express, Port Elizabeth Express, Theewaterskloof Gazette, Paarl Post, Eikestad Nuus and Swartland Gazette.

8 P Malan, Hangklip Conservancy, Personal communication 19 October 2020.

9 S v Blignault [2019] JOL 44135 (ECP).

10 M Isaacs and E Witbooi, Fisheries crime, human rights and small-scale fisheries in South Africa: a case of bigger fish to fry, Marine Policy, 105, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.023; K de Greeff, Want to curb poaching? Treat the cause, 28 February 2018, www.groundup.org.za/article/want-curb-abalone-poaching-treat-cause/ (accessed 21 October 2020).

11 K Goga, The illegal abalone trade in the Western Cape, ISS Paper 261, Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2014, 5.

12 Goga, The illegal abalone trade in the Western Cape, 9.

13 Isaacs and Witbooi, Fisheries crime, 159.

14 S Moneron, D Armstrong, D Newton, The people beyond the poaching: interviews with convicted offenders in South Africa, TRAFFIC, September 2020, www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/13126/web-beyond-the-poaching-offender-survey.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020), 14.

15 Goga, The illegal abalone trade in the Western Cape, 6.

16 E Muchapandwa, K Brick, M Visser, Abalone conservation in the presence of drug use and corruption: Implications for its management in South Africa, International Journal of Sustainable Economics, 6:2, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSE.2014.060348. [ Links ]

17 S Raemaekers, M Hauck, M Bürgener, A Mackenzie, G Maharaj, É Plagányi, P Britz, Review of the causes of the rise of the illegal South African abalone fishery and consequent closure of the rights-based fishery, Ocean and Coastal Management, 54, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.02.001. [ Links ]

18 S Raemaekers and P Britz, Profile of the illegal abalone fishery (Haliotis midae) in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa: Organised pillage and management failure, Fisheries Research, 97, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2009.02.003. [ Links ]

19 M Shaw, Organised crime in post-apartheid South Africa, Safety and Governance Programme, Institute for Security Studies, Occasional Paper No 28, January 1998. J Platt, Poachers steal 7 million South African abalones a year, Scientific American, 5 February 2016, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/extinction-countdown/poachers-abalone/#:~:text=According%20to%20data%20 presented%20this,and%20as%20a%20purported%20aphrodisiac (accessed 21 October 2020).

20 W Gumede, SA becoming a country of parallel states, Sunday Times, 18 October 2020, 20.

21 M Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa: The case of the abalone fishery, Acta Jurídica, 56, 1999, 211, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/actj1999&i=223. [ Links ]

22 P Gastrow, Triad societies and Chinese organised crime in South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, Occasional Paper No. 48 (2001), 8.

23 J Grobler, Exposing the abalone-rhino poaching links, Oxpeckers, March 2019, https://oxpeckers.org/2019/03/abalone-rhino-poaching-links/ (accessed 21 October 2020).

24 R Baird, Aspects of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in the Southern Ocean, Berlin: Springer, 2006, 8; [ Links ] E De Coning and E Witbooi, Towards a new fisheries crime paradigm: South Africa as an illustrative example, Marine Policy 50, 2015, 211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.06.024. [ Links ]

25 K De Greeff and S Raemakers, South Africa's illicit abalone trade: an updated overview and knowledge gap analysis, Cambridge: TRAFFIC International, 2014, 6.

26 S24 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution).

27 Seafish, A report of the seafish industry in South Africa, undated, www.seafish.org/media/775685/south%20africa.pdf (accessed 7 March 2020).

28 GM Branch, M Hauck, N Siqwana-Ndulo and AH Dye, Defining fishers in the South African context: subsistence, artisanal and small-scale commercial sectors, South African Journal of Marine Science, 24, 2002, 475-476. [ Links ]

29 WWF South Africa v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2019 (2) SA 403 (WCC), par [4].

30 Coastal Links Langebaan and Others v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and Others [2016] ZAWCHC 150; [2017] 2 All SA 46 par [8] - [11]. M Sowman, J Sunde, S Raemaekers and O Schultz, Fishing for equality: policy for poverty alleviation for South Africa's small-scale fisheries, Marine Policy 46:31, 2014, 33-34. [ Links ]

31 Gongqose and Others v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Others, Gongqose and S 2018 (5) SA 104 (SCA) par [39].

32 FAO, Fisheries Division, www.fao.org/fishery/facp/ZAF/en#CountrySector-SectorSocioEcoContribution (accessed 20 October 2020).

33 Marine Living Resources Act (Act 18 of 1998).

34 Others include Cape Nature and SANParks. The Overstrand Municipality has a law enforcement unit, and the City of Cape Town has marine units in its metro police, as well as in its law enforcement department.

35 M Norton, First steps to tackling South Africa's abalone poaching, The Conversation, 21 November 2018, www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2018-11-23-first-steps-to-tackling-south-africas-abalone-poaching (accessed 2 April 2020).

36 N Okes, M Burgener, S Moneron and J Rademeyer, Empty Shells: an assessment of abalone poaching and trade from southern Africa, TRAFFIC, September 2018, www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/11065/empty_shells.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020), 1.

37 FAO, Fisheries Division.

38 SABC News, 22 October 2020.

39 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in Montego Bay on 10 December 1982, entered into force on 16 November 1994.

40 Preamble of UNCLOS.

41 UNCLOS, Article 61.2.

42 UNCLOS, Article 62.1.

43 WWF South Africa v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, par [36].

44 Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, 2016, www.fao.org/3/a-i6069e.pdf (accessed 7 March 2020).

45 Examples include the 1993 FAO Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas, the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement aimed at ensuring the long-term conservation and sustainable use of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks, the 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, the 2001 International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (IPOA-IUU), the 2009 FAO Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate, Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (PSMA) and the 2014 Voluntary Guidelines for Flag State Performance.

46 FAO, Combatting and eliminating illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing in the Asia-Pacific region, 2019, www.fao.org/3/ca4509en/ca4509en.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 2; FAO, Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, 2016, www.fao.org/3/i6069e/I6069E.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 1; UNODC, Crime and development in Africa, 2005, www.unodc.org/documents/research/Africa_%20Report_full_2005.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 89; UNODC combating transnational organised crime committed at sea, Issue Paper, 2013, www.unodc.org/documents/organized-crime/GPTOC/Issue_Paper_-_TOC_ at_Sea.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 4; Fish-i Africa, Illegal fishing? Evidence and analysis, 2017, https://stopillegalfishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Illegal-Fishing-Evidence-and-Analysis-WEB.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 28; FAO, Report of the Second Meeting of the Part 6 Working Group established by the Parties of the Agreement on the Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, 2018, www.fao.org/3/ca2897en/CA2897EN.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 2; FAO, Joining forces in the fisheries sector: promoting safety, decent work and the fight against IUU fishing, 2018, www.fao.org/3/cb1588en/CB1588EN.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 3.

47 Marine Resources Assessment Group, Final Report for the UK's Department for International Development, 68.

48 FAO, Implementation of the international plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, 2002, www.fao.org/3/y3536e00.htm (accessed 1 November 2020) xi.

49 United Nations, Sustainable Development Goals: the sustainable development agenda, www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed 20 October 2020).

50 Ibid.

51 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996, section 24(b).

52 GNR 1111 in GG 19205 dated 2 September 1998.

53 MLRA, section 2(b).

54 MLRA, section 2(i).

55 Section 9 of the MLRA.

56 Section 51 of the MLRA.

57 Sections 19-21 of the MLRA.

58 The Minister responsible for fisheries suspended all commercial abalone fishing in October 2007, with effect from 1 February 2008. DEAT, 2007. Draft guidelines for marine ranching in South Africa, Marine and Coastal Management, Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Pretoria, South Africa.

59 Section 1 of the MLRA.

60 Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa, 213.

61 WWF South Africa v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2019 (2) SA 403 (WCC), par [36].

62 Okes, et al., Empty shells.

63 Through systems such as mariculture.

64 UNODC, Combating transnational organised crime committed at sea, 4; De Coning and Witbooi, Towards a new fisheries crime paradigm, 211; Institute for Security Studies, Organised crime in post-Apartheid South Africa, Occasional Paper 28, 1998, 2; Hubschle, Organised crime in Southern Africa, First Annual Review, 2016, 7.

65 S v Selecta Sea Products (Pty) Ltd [1994] ZASCA 103. Prosecuted under the Sea Fisheries Act 1973 (Act 58 of 1973) the Fishing Industry Development 1978 (Act 86 of 1978), and the Exchange Control Regulations, GN R1111 of 1 December 1961.

66 S v Roberts 2013 (1) SACR 369 (ECP).

67 Act 121 of 1998.

68 In terms of the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication Related Information 2002 (Act 10 of 2002).

69 United States v. Bengis, 631 F.3d 33, 35, 88 CrL 518 (2d3Cir. 2011) WL 2922292, 2013.

70 Meyer, Restitution and the Lacey Act: new solutions, old remedies, Cornell Law Review 93(4) (2008), 851.

71 The accused were charged, including for fraud, corruption and bribery under the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act 2004 (Act 12 of 2004) and racketeering under POCA, violations of the Marine Living Resources Act 1998 (Act 18 of 1998) and offences under the Customs and Excise Act 1964 (Act 91 of 1964).

72 United States Lacey Act, 16 U.S.C. § 3372(a)(2)(A).

73 As quoted by Judge Lewis A. Kaplan of the US District Court when he sentenced Bengis to 46 months imprisonment for his leading role in these crimes.

74 As described in G Bruce Knecht, Hooked: pirates, poaching, and the perfect fish, Rodale, 2006.

75 UNODC, Crime and development in Africa: crime and drugs as impediments to security and Development in Africa strengthening the rule of law, 2005, www.unodc.org/documents/archive/aide%20memoire.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020) 29; Hubschle, First Annual Review 3.

76 FAO, Implementation of the international plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, xi.

77 Raemaekers and Britz, Profile of the illegal abalone fishery.

78 D Belhabib and P Le Billon, Editorial: Illegal fishing as a trans-national crime, Frontiers in Marine Science, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00162c (accessed 12 April 2020).

79 Sundström, Corruption in the commons: why bribery hampers enforcement of environmental regulations in South African fisheries, Internationa Journal of the Commons 7:2, 2013, 454. [ Links ]

80 A Hyman, and B Jordan, Officials charged with corruption over abalone poaching are back at work, Sunday Times Live, 20 June 2018, www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-06-20-officials-charged-with-corruption-over-abalone-poaching-are-back-at-work/ (accessed 10 April 2020).

81 K de Greef, Fisheries department rotting from the top, News24, 13 November 2018, www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/fisheries-department-rotting-from-the-top-20181113 (accessed 10 April 2020).

82 R Chelin, Can the illegal abalone trade be stopped?, ISS Today, 21 November 2018, www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-11-21-can-the-illegal-abalone-trade-be-stopped/ (accessed 6 April 2020).

83 Hubscview V

84 Ibid.

85 P Steyn, Poaching for abalone, Africa's 'white gold,' reaches fever pitch, National Geographic, 14 February 2017, www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2017/02/wildlife-watch-abalone-poaching-south-africa/ (accessed 27 April 2020).

86 See section 9 of the MLRA that gives the Minister the power to appoint Fishery Control Officers (FCOs) and section 51 that sets out the powers of FCOs.

87 GN R1111 in GG 19205 of 2 September 1998.

88 Long title and section 2 of the MLRA.

89 DAFF, Compliance, (undated), www.daff.gov.za/daffweb3/Branches/Fisheries-Management/Monitoring-Control-and-Surveillance (accessed 19 May 2019).

90 'Compliance' refers to inspection (mostly) of vessels. DAFF, Compliance, (undated), www.daff.gov.za/daffweb3/Branches/Fisheries-Management/Monitoring-Control-and-Surveillance/compliances (accessed 2 August 2019).

91 The Monitoring and Surveillance Directorate was formerly known as the Special Investigations Unit and exists to investigate and secure prosecution of high-profile offenders and syndicates. See DAFF, Monitoring and surveillance, (undated), www.daff.gov.za/daffweb3/Branches/Fisheries-Management/Monitoring-Control-and-Surveillance/MONITORSURVIELLANCE (accessed 2 August 2019).

92 DAFF, Fisheries Protection Vessels, (undated), www.daff.gov.za/daffweb3/Branches/Fisheries-Management/Monitoring-Control-and-Surveillance/FISHPVESSELS (accessed 2019-08-02).

93 Governed by the South African Police Services Act 1995 (Act 68 of 1995).

94 GN R2418 in GG 21310 of 30 June 2000.

95 Section 63(1)(b) of the MLRA; DJ Crookes, Trading on extinction: an open-access deterrence model for the South African abalone fishery, South African Journal of Science, 112:3/4, 2016, 1, https://dx.doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/20150237; [ Links ] S Moneron, D Armstrong, D Newton, The people beyond the poaching, 22.

96 K Goga, The illegal abalone trade in the Western Cape, ISS Paper261, Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2014. Seized lobster are destroyed.

97 Crookes, Trading on extinction, 1.

98 Goga, The illegal abalone trade in the Western Cape, 8.

99 It is only recently that the Western Cape police decided to treat abalone poaching as a priority crime. Maroela Media, Perlemoenstropery nou ernstige prioriteitsmisdaad (28 November 2019) https://maroelamedia.co.za/nuus/sa-nuus/perlemoenstropery-nou-ernstige-prioriteitsmisdaad/ (accessed 20 October 2020).

100 M le Roux, The case for organised crime, 2019, FishFORCE Strategic Conversation, https://fishforce.mandela.ac.za/ (accessed 20 October 2020).

101 SAPS, Annual Report 2017/18, 183.

102 Crookes, Trading on extinction, 1.

103 Times Live, 48 suspected abalone poachers arrested in garden Route swoop, Sunday Times Live, 24 January 2020, www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2020-01-24-48-suspected-abalone-poachers-arrested-in-garden-route-swoop/ (accessed 10 April 2020).

104 Crookes, Trading on extinction, 7.

105 G Becker, Crime and punishment: an economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76:2, 1968, http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/259394 (accessed 1 November 2020)

106 Crookes, Trading on extinction, 1.

107 Becker, Crime and punishment.

108 Organised crime investigating officer, Port Elizabeth, personal communication, 6 August 2019.

109 The case eventually culminated in Groenewald and Others v S (A668/2010) [2019] ZAWCHC 170 (10 December 2019).

110 D Chambers, Preacher and son jailed 20 years after their arrest for abalone poaching, Sunday Times Live, 12 December 2019, www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2019-12-12-preacher-and-son-jailed-20-years-after-their-arrest-for-abalone-poaching/ (accessed 21 April 2020).

111 Information supplied by advocate M le Roux, senior state advocate of the National Prosecuting Authority in an e-mail dated 18 November 2019.

112 HJ van As, Fisheries crimes must be priority, The Herald, 9 October 2019, 3.

113 Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa, 214.

114 W Lau, An assessment of South African dried abalone Haliotis midae consumption and trade in Hong Kong, TRAFFIC International, 2020, 116.

115 See, for example, Parliamentary Monitoring Group, Small-scale fisheries policy implementation; fishing rights allocation process 2020, DAFF progress report, 7 November 2017, https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/25420/ (accessed 10 December 2019).

116 Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa, 222.

117 A Sundström, Covenants with broken swords: corruption and law enforcement in governance of the commons, Globä Environmental Change, 31, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.02.002.

118 See in general WWF South Africa v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2019 (2) SA 403 (WCC).

119 Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa, 218.

120 E De Coning, Fisheries Crime in L Elliott and W Schaedla (eds), Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime, London: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016. [ Links ]

121 Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa, 211.

122 Gastrow, Triad societies and Chinese organised crime in South Africa.

123 Crookes, Trading on extinction, 8.

124 Hauck, Regulating marine resources in South Africa: The case of the abalone fishery, 219.

125 RB Cabral, J Mayorga, M Clemence et al., Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0499-1. [ Links ]

126 UR Sumaila, W Cheung, A Dyck, et al,. Benefits of rebuilding global marine fisheries outweigh costs, PLoS ONE, 7:7, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040542. [ Links ]

127 Ibid.

128 Cabral et al, Rapid and lasting gains from solving illegal fishing, 1.