Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Crime Quarterly

versión On-line ISSN 2413-3108

versión impresa ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. no.69 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2020/i69a5289

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Deaths due to police action and deaths in custody - A persistent problem in Pretoria, South Africa

Shimon Barit; Lorraine du Toit-Prinsloo; Gert Saayman1

sbarit@gmail.com; lorrainedutoitprinsloo@gmail.com; gert.saayman@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In 2013, South Africa had the second highest rate of imprisonment in Africa. During the apartheid era, a substantial number of deaths in custody involved political detainees. However, two decades after the abolition of apartheid there continues to be a high number of deaths in custody and deaths due to police action.

There is no internationally standardised classification for deaths which take place in custody and/or due to police action. For purposes of this study, we divided these cases broadly into two categories: firstly, deaths which took place as a result of police action as well as deaths of persons held in police custody, and secondly, deaths of inmates of correctional service facilities. We conducted a retrospective descriptive case audit at the Pretoria Medico-Legal Laboratory (PMLL) of all cases admitted as deaths as a result of police action, deaths in police custody and deaths in correctional service facilities during the five year period from January 2007 through December 2011. A total of 93 cases were identified, which included 48 deaths due to police action, 28 deaths in police custody and 17 deaths in correctional service custody. The majority of these deaths were due to gunshot wounds (n=48) - all due to police action. Hangings accounted for 17 cases, and the majority of these occurred in police holding cells. This study highlights the relatively large numbers of firearm fatalities related to police action. In contrast to similar studies elsewhere, we identified no deaths associated with illicit drug intoxication or due to phenomena such as excited delirium. We argue that there is a need for objective, impartial and competent medico-legal investigation into deaths of this nature.

Introduction

In all communities, deaths which result from police action or which take place while a person is in custody are problematic. These cases often result in intense media coverage, criticism and even community upheaval - especially when there may be political connotations. There is no internationally standardised classification of such 'deaths in custody'.2 How one defines and categorises of this broadly encompassing group of deaths will depend, among other things, on the legislative provisions in a particular country or on parameters and criteria as proposed by humanitarian and watchdog agencies, such as Amnesty International and the United Nations, who may monitor and report on these deaths.3

Deaths in custody may be broadly classified into two groups. The first group are deaths that result from police or security force action, mostly during pursuit operations or in the apprehension of suspects. The second group are deaths of individuals who have been remanded in custody - either prior to a bail hearing or while awaiting trial (usually still in police custody) or after court sentencing (usually in the care of correctional service agencies). In South Africa, the Independent Police Complaints Investigative Directorate Act (Act 1 of 2011) created the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) in order to ensure independent oversight of the South African Police Service, among other things. This agency had previously existed as the Independent Complaints Directorate (ICD). IPID is now responsible for investigating all deaths in police custody and deaths due to police action.4

According to section 15(1) of the Correctional Services Act 1989 (Act 111 of 1998) all deaths among prison inmates (i.e. in correctional facilities) which cannot be certified by a medical practitioner as having been due to natural causes, must be reported to the police for investigation in accordance with the Inquests Act 1959 (Act 58 of 1959). However, subsection 15(2) of the Correctional Services Act also states that all deaths of inmates (i.e. natural and unnatural) must be reported to the Inspecting Judge of the Judicial Inspectorate of Correctional Services (JICS), for investigation.

According to official annual reports released by IPID, 792 persons died in SA as a result of police action or while in police custody in 2007/2008, with 912 such cases reported during 2008/2009.5 The Judicial Inspectorate of Prisons (JICS) has reported a substantially larger number of number of deaths among prison inmates in the past. JICS reported 1 047 deaths in 2009/2010,6 and 852 deaths in 2011/2012,7 with 55 and 48 deaths respectively due to unnatural causes, among a prison population of approximately 166 000 people during that period.8

The World Prison Population List (2013) showed that on the African continent, South Africa rated second only to Rwanda in having the highest rate of incarceration (reported to be 294 per 100 000 of the population, with a total inmate count of 156 370 in 2013). Globally, among countries with a population exceeding 50 million people, only the US and the Russian Federation had higher rates of imprisonment.9 To be able to meaningfully assess and compare the numbers of deaths in detention and the mortality rates of detained and imprisoned persons, we must carefully analyse these against the general and prison populations. Studies have shown that inmates of penitentiaries are more likely to suffer from infectious diseases and mental illness, or succumb to unnatural deaths such as suicide, when compared with the general population.10Based on the high number of prisoners in South Africa, relatively large numbers of in-prison deaths are to be expected.

Deaths in custody are not a new problem in South Africa, given its troubled recent political past. During the struggle against the apartheid regime, a large number of political detainees died while in the custody of the police and/or state security service officers. Two particularly well-known examples include those of Ahmed Timol and Steve Biko.11 In August 2017, the inquest into the death of Ahmed Timol was reopened, some 45 years after the original inquest was held in 1972.12 In contrast to the findings of the first inquest, which had held that the deceased had committed suicide by jumping from a building, Judge Billy Mothle found that Timol's death had resulted from him being pushed from the building. Murder charges have now been brought against at least one of the police officers believed to have been involved in Timol's death. The reopened inquest, much like the original inquest, included a very detailed scrutiny of the medico-legal autopsy findings.13

Decades after the advent of democracy in South Africa, deaths in detention, including deaths due to police action, are still a contentious and relatively frequent phenomenon. In 2011, Andries Tatane was fatally beaten and shot by police during a protest march. The events were witnessed on video footage. Yet, none of those implicated in his death were brought before court as the specific offenders could not be identified due to the protective helmets which they wore at the time.14 In 2012, 34 striking miners were fatally shot by police during the Lonmin Mine strike in what became known in the media as the Marikana Massacre.15 A judicial commission of inquiry was appointed to investigate the Marikana deaths, and the presiding officer, Judge Ian Farlam, subsequently recommended that the Director of Public Prosecutions should carry out a special investigation into the police's use of excessive force at Marikana.16 To date, no one had been found guilty of any wrongdoing, although investigations are ongoing.

According to international norms, unnatural and unlawful deaths of persons who are in custody or those which associated with police action, must be thoroughly investigated - preferably by an independent body.17 The Minnesota Protocol18 and, in cases of alleged abuse and torture, the Istanbul Protocol19 provides guidance on how these investigations should be carried out. The scope and aims of the Minnesota Protocol include the investigation of unlawful deaths in custody or detention, providing specific guidelines for forensic pathologists and reiterating the importance of fully documenting personal identifying characteristics, injuries, comorbidities and the causes and mechanisms of death. Anatomical sketches and detailed templates for use in these investigations are attached to the protocol as annexures.20 The Istanbul Protocol specifically sensitises investigators to torture and other forms of cruel and inhumane treatment and advises on the proper investigation and documentation of findings.21

The medico-legal investigation of deaths in detention and deaths due to police action present particular problems for coroners, medical examiners and forensic pathologists the world over. The reasons for this vary. These cases must not only be thoroughly investigated and meticulously recorded (as prescribed by the abovementioned protocols), but also often present particular diagnostic problems given the presence of complex phenomena such as positional and restraint asphyxia, 'suicide by cop', exertional deaths and excited delirium, to name a few.

Although agencies like IPID and the JICS regularly prepare official reports that review deaths due to police action and other deaths in custody, there has been little reporting in South Africa on findings emanating from the medico-legal investigation performed by forensic medical practitioners. One previous study on custody-related deaths in South Africa has been published, describing 117 cases which took place in Durban between 1998 and 2000. Eighty-eight of these deaths were due to police shootings.22

The profile and prevalence of deaths which occur as a result of police action (during the pursuit and arrest phases) and during detention (prior to transfer to penitentiaries) differ substantially. Separate studies are therefore required to properly compare South Africa with other countries. Here too, careful consideration of the appropriate population denominators is required in order to draw any parallels. Despite these differences, all studies that focus on the investigative aspects, incidence and profile of these problematic cases can help us better understand and prevent these unfortunate outcomes. This study aimed to review aspects of the medico-legal investigation pertaining to deaths of persons which resulted from police action and/or who were in custody (both in police holding cells as well as in correctional service facilities) in the Pretoria (Tshwane) region over a five year period (2007-2011). Pretoria is the capital city of South Africa, and the greater Pretoria region includes 31 police stations/ precincts as well as one large correctional service facility.23 The Pretoria Medico-Legal Laboratory (PMLL) serves the greater portion of the city, performing approximately 2 000 medico-legal investigations (autopsies) annually.

Methods

A retrospective descriptive case audit was conducted on the case files of the PMLL on all deceased persons admitted as having died as a result of police action or while in police or correctional service custody, for the period 1 January 2007 through 31 December 2011. The case audit included a review of information contained in the admissions register and the PMLL case files.

The data were analysed using descriptive statistics (SAS® 9.3) with assistance from the Department of Statistics at the University of Pretoria. This study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria prior to commencement (Research Ethics reference number 43/2012). This article presents results from the original study, which was conducted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Master's degree in Medical Criminalistics at the University of Pretoria.24

Results

A total of 93 cases were identified for inclusion in the study. These included 76 deaths investigated by IPID and 17 deaths reported to the JICS. Table 1 shows that the majority of the deaths investigated by IPID were related to police action (n=48) while a further 28 deaths occurred while the decedents were in police custody. The average total annual case load admitted to the PMLL during the period under study was 2 283 cases per year. Deaths in custody contributed between 11 and 25 cases per year, with a mean of 18.8 deaths per year, or approximately 1% of the total annual case load.

Demographic details

There were 89 males and four females among the decedents, with an overall ratio of 22.2:1. There were no female deaths in correctional services institutions.

The age distribution for deaths in custody ranged from 16-61 years, with a mean age of 32 years. The mean ages for deaths investigated by IPID and the JICS were 31 years and 39 years respectively.

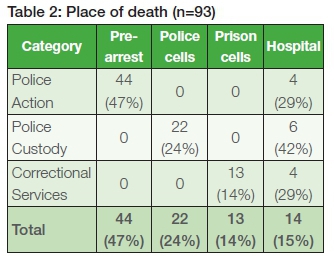

Place/setting of death

Table 2 shows the places or setting where the deaths occurred. Of the 93 cases reported on in this study, 44 of the deaths (47%) were found to have occurred in the pursuit and/ or pre-arrest stage (i.e. deemed to have been related to police action). Deaths in police custody mostly occurred in the holding cells due to hanging, with 10 deaths occurring among persons who had been admitted to hospital, after pursuit and/or arrest proceedings or after having been admitted to police holding cells. The latter group included three cases where the deceased had sustained gunshot wounds that were inflicted by the police and one case where the decedent had sustained injuries in a motor vehicle accident following police vehicle pursuit.

In total, 17 of the 93 cases reported on here took place among inmates in the custody of the Department of Correctional Services (DCS). Thirteen of these people died in prison cells and four died in hospitals and clinics administered by DCS.

Inter-agency collaboration

A forensic medical practitioner attended the scene of death in 16 cases (17% of the cases under discussion). Deaths scenes were attended in most cases where the victim had died while in custody (police holding or correctional service prison cells). Few death scenes which involved police action (mostly shootings) were attended by a forensic medical practitioner. The Minnesota Protocol prescribes that a forensic doctor or pathologist should attend these death scenes upon request of the police.25 A representative of IPID attended the post-mortem examination in 47 of the 76 cases (62%) that fell within their jurisdiction.

Medico-legal investigation

A full autopsy, which entails external examination followed by evisceration and dissection of all organs, was conducted on all cases. In 56 of the 93 cases (60%) the autopsy was performed by a registered specialist forensic pathologist, while the rest were performed by trainee pathologists (registrar or resident) under the supervision of a pathologist.

Special investigations

Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was determined in 88 cases. The majority of these tests (72%) yielded a negative result (zero value) but in ten cases (11%) a BAC in excess of 0.05g/100ml was reported - the highest value being 0.39g/100ml.

Toxicological analyses were requested in 20 cases (22% of the cases under review). In the majority of these cases (80%) the results of these tests were still pending upon completion of the study, as there is an extra-ordinary delay (often in excess of two years) in finalising the analyses at the state forensic chemistry laboratory. Among the cases for which results were available, only one case tested positive for illicit drugs (cocaine) and one for prescription medication.

Histology was performed in 42 cases (45% of the cases under review). In 13 cases, the histological examination confirmed the cause of death and in one case the cause of death was primarily established by means of histological examination. In the remaining 28 cases, the histological examination of tissue slides did not materially contribute to the formulation of the cause of death.

Cause of death

Table 3 depicts the cause of death for each of the police action, police custody and correctional service custody categories of cases. Gunshot wounds were the single most frequent cause of death, accounting for 48% of cases under review (n=48), with all of these being due to police action. The most common cause of death while in police custody was hanging (n=13). There were 11 cases of natural death, the majority of which occurred in correctional service facilities. These deaths were mostly due to underlying natural disease conditions including cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases such as ischaemic heart disease and pulmonary tuberculosis.

Manner of death

Upon completing the medico-legal examination, the attending pathologist usually makes an informal finding as to the probable manner of death. Based on these assessments, a finding of homicide was made in 48 cases (52% of the 93 cases under review), with these deaths most commonly occurring during police action. In 17 cases (18% of total) the manner of death was suicide - all of these being due to hanging. Death was deemed to have been due to natural causes in 11 cases (12%). Only six of the deaths were classed as accidental (6% of the total number of cases). Of the four deaths which took place in DCS hospital settings, two were due to natural causes, one was due to hanging (while in hospital) and in one the manner of death was deemed "undetermined". Overall, the manner of death was reported as "undetermined" in 11 cases. It should be noted that the assessment of manner of death by the attending pathologist is not an official or judicial finding, which can only be determined after the prescribed inquest or judicial review.

Firearm related fatalities

As Table 3 shows, there were 44 firearm fatalities, which all occurred due to police action during the pursuit and arrest phase. All of these cases were classed as homicides. In 26 cases (59%) the victims sustained multiple gunshot wounds. Gunshot wounds involved the head and neck in 14 cases, the chest and abdomen in 34 cases and the upper and lower extremities in 14 and 12 cases respectively. Interestingly, 16 gunshot wounds were situated on the posterior aspects of the bodies of decedents, which indicates that the decedent was shot from behind. Although not routinely reported in the autopsy, based on the nature of the wounds it appears that firearms most frequently implicated in these deaths were handguns. Police officers are typically issued with 9mm parabellum service pistols.

Hanging cases

There were 17 cases of hanging, of which 13 occurred in police custody and four in correctional service facilities. The ligature was present at autopsy in all but one case. Items of clothing were used in 13 cases (76%) and bed linen was used in four cases (24%). No shoelaces were used as ligatures.

Blunt force trauma

Four persons died as a result of injuries sustained in motor vehicle collisions during pursuit operations. Five decedents died of blunt force injuries while in police holding cells. In three of these cases the manner of death was homicide, and the remaining two cases were undetermined.

Discussion

In order to meaningfully report on and compare deaths due to police action and deaths in detention it would be best to follow internationally standardised definitions and categorisations. Ruiz et al have previously called for a more standardised approach to the investigation of these deaths, including assessments of the place of death and the precise time frame following arrest or incarceration, given that many of these deaths take place shortly after arrest.26Notwithstanding this limitation pertaining to case definition, efforts should be made to compare the rate, nature and circumstances surrounding these deaths in different communities and jurisdictions.

The most striking finding of our study may be the fact that there were 44 fatal shootings by police during the phases of pursuit and arrest, with only a small number of deaths in this category being due to other forms of trauma. None of the cases appeared to related to problematic phenomena such as excited delirium and restraint or positional asphyxia. Our study correlates with the findings previously reported by Bhana in Durban where the majority of the fatalities associated with police action were due to the use of firearms.27

This particular finding may reflect legislative provisions and the disposition or propensity of the police to use firearms. It may also reflect the prevalence of possession of firearms and the willingness of suspects and the police to use them. This finding may also be less surprising in light of a previous public statement made by a national Minister of Police that police officers should 'shoot to kill'. This may reflect the level of violent confrontation and/or aggression that exists between police officers and suspects in this country.28

While not reported upon by us, it is important to consider that many police officers are also shot in the line of duty by suspects. Bhana reports, for example that 'the high risk of fighting crime in South Africa is leading to a death rate among SAPS members that is ranked among the highest in the world.'29 Media reports indicate that 109 South African Police Service members were listed as killed while on duty in 2009 and a further 110 reported in 2010.30 It would seem that a detailed study of the circumstances surrounding these deaths is warranted.

The apparent absence of deaths associated with physical restraint during or after arrest is noteworthy, particularly since this has been quite commonly reported in other countries and jurisdictions. Furthermore, the absence of deaths ascribed to excited delirium and deaths which may possibly be ascribed to the prior intake of illicit drugs, despite the high level of use of illicit substances in SA, should also be noted. It is particularly worrisome that there are exceedingly long delays in toxicological diagnostic support for pathologists in their investigation of these cases.

Suicidal death in our study occurred mostly in police holding cells, most commonly due to hanging. This correlates with studies by Kubat et al in the Netherlands and Bardale et al in India, who found that the majority of suicidal deaths occurred in police lock-up cells.31These authors recommended that efforts should be made to reduce the risk of suicide in these settings. Okoye et al reported on an earlier study from Nebraska (for the period 1991-1996), where there were 17 suicides, comprising 33% of the study population.32Suicide prevention strategies were consequently introduced state-wide in correctional facilities. Following this intervention (in 2003 to 2009) there were only eight cases of suicide (21% of the study population).33

Our study further suggests that there is relatively poor interagency collaboration in the investigation of these deaths: the forensic medical practitioner attended the scene of death in only 16 cases and IPID investigators attended the medico-legal autopsy in only 47 of the 76 deaths falling under their jurisdiction. Although there is no explicit instruction that IPID investigators should attend autopsies at medico-legal mortuaries, the failure to establish direct inter-agency contact at the scene of death or at the mortuary may result in parties tending to work in silos, with suboptimal inter-agency exchange of information. A detailed and standardised protocol driven medico-legal investigation in all these cases will serve to elucidate individual events and to shed light on the collective nature of these events. Wangmo et al have similarly stressed the importance of proper medico-legal examination of these cases.34

The 2011/2012 Annual Report of the JICS indicates that over 90% of inmate deaths in DCS facilities were due to natural causes.35 None of these deaths are subject to contemporaneous or later medico-legal investigative review, as medical practitioners in the employee of (or contracted by) DCS issue death certificates which allow for burial of deceased individuals without further case specific review. This stands in contrast to the legal requirement in many countries and protocols proposed by civilian watchdog agencies which prescribe specific coronial or medico-legal review of all such deaths in state institutions such as prisons, mental hospitals. This usually requires that such deaths be reported to coroners or medical examiners, implying some measure of scrutiny by forensic medical practitioners, even though autopsies may not routinely be carried out in all such cases.

Conclusion

This study reports on the findings of the medico-legal investigation of death in almost a hundred instances of persons who died as a result of police action or while in police and correctional service detention, from non-natural or unexplained causes, over a five-year period. The vast majority of these deaths were the result of shootings of suspects by police officers during pursuit and arrest operations, while a substantial number of suicides accounted for the second most common manner of death. Our study furthermore highlights that these cases are perhaps sub-optimally investigated from a medico-legal perspective, with relatively poor interagency collaboration and that closer attention may be paid to standardised approaches as prescribed in documents such as the Minnesota Protocol. We therefore propose that efforts be made to introduce measures to ensure a more systematic and protocol driven review all such deaths. In addition, consideration should be given to extending the obligatory review of all deaths of inmates in DCS facilities, by qualified forensic medical practitioners. The collective findings of such investigative programs should serve to inform policies and procedures which seek to minimise these unfortunate fatalities.

Notes

1 Shimon Barit is a Masters of Medical Criminalistics graduate from the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Pretoria; Lorraine du Toit-Prinsloo is a forensic pathologist appointed as an extraordinary lecturer in the Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Pretoria; Gert Saayman is the Head of Department of Forensic Medicine at the University of Pretoria and Head: Clinical Department, Forensic Pathology Service, Pretoria, South Africa.

2 T Wangmo, G Ruiz, J Sinclair et al., The investigation of deaths in custody: A qualitative analysis of problems and prospects, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 25, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2014.04.009. [ Links ]

3 Amnesty International, Detention and Imprisonment, https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/detention/ (accessed 18 August 2019); United Nations Human Rights Council, Out of sight, out of mind: Deaths in detention in the Syrian Arab Republic, 31 session Agenda, item 4, Human rights situations that require the Council's attention, 2016, A/ HRC/31/CRP.1, www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/CoISyria/A-HRC-31-CRP1_en.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019); Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in cooperation with the United Nations Support Mission in Libya, Abuse behind bars: Arbitrary and unlawful detention in Libya, 2018, www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/LY/AbuseBehindBarsArbitraryUnlawful_EN.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019).

4 Section 28 of the Independent Police Investigative Directorate Act 2011 (Act 1 of 2011).

5 Independent Police Investigative Directorate, Annua Report 2008/2009, Pretoria: Independent Police Investigative Directorate, 2009, 46 and 51, www.ipid.gov.za/sites/default/files/documents/Annual%20Report%202008-09.pdf, (accessed 3 February 2019). We reference statistics from the 2008/2009 time frame as they fall within the period covered by our study.

6 Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services, Annual Report, 2009/2010, https://acjr.org.za/resource-centre/jics-annual-report-2009-2010.pdf (accessed 29 June 2019).

7 Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services, Annual Report 2011/2012, Durban and Cape Town: Office of the Inspecting Judge, Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services, 2012, 23, 50, 51, http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/docs/121011judicialannual.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019).

8 Ibid.

9 R Walmsley, World Prison Population List, 10 ed, London: International Centre for Prison Studies, 2013, www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_10.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019).

10 S Fazel, J Baillargeon, The health of prisoners, Lancet 377:956-65, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7; LA Stewart, A Nolan, J Sapers, et al, Chronic health conditions reported by male inmates newly admitted to Canadian federal penitentiaries, CMAJ Open, 3:1, E97-102, 2015, http://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20140025.

11 South African History Online, The death in police custody of Ahmed Timol, politica activist and underground operative, is confirmed, www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/death-police-custody-ahmed-timol-political-activist-and-underground-operative-confirmed (accessed 3 February 2019);

H Bernstein, The death of Steve Biko, South African History Online, www.sahistory.org.za/archive/iv-death-steve-biko (accessed 3 February 2019).

12 High Court of South Africa Gauteng Local Division, Johannesburg (Case number 76755/2018).

13 Ibid.

14 South African History Online, The death of Andries Tatane in service delivery protest in the Free State sparks national outrage, www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/death-andries-tatane-service-delivery-protest-free-state-sparks-national-outrage (accessed 3 February 2019).

15 A Harding, Marikana massacre: should police be charged with murder? BBC News, 14 November 2014, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30002242 (accessed 3 February 2019). [ Links ]

16 IG Farlam, Marikana Commission of Inquiry, Report on matters of public, national and international concern arising out of the tragic incidents at the Lonmin mine in Marikana, in the North West Province, www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/marikana-report-1.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019).

17 Wangmo et al., The investigations of deaths in custody

18 Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), The Minnesota Protocol on the investigation of potentially unlawful death (2016): The revised United Nations manual on the effective prevention and investigation of extra-legal, arbitrary and summary executions, New York and Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2016, www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/MinnesotaProtocol.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019).

19 OHCHR, Istanbul Protocol: Manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, New York and Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2004, HR/P/PT/8/Rev.1, www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/training8Rev1en.pdf (accessed 3 February 2019).

20 OHCHR, The Minnesota Protocol.

21 OHCHR, Istanbul Protocol: Manual on the effective investigation and documentation of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/training8rev1en.pdf.

22 BD Bhana, Custody-related deaths in Durban, South Africa 1998-2000, The American Journa of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 24:2, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.paf.0000069849.70216.4b. [ Links ]

23 City of Tshwane, Police station listing, available from: http://www.tshwane.gov.za/sites/Departments/Metro-Police/Pages/Police-Station-Listing.aspx (accessed 18 August 2019).

24 S Barit, The medico-legal investigation of deaths in custody: A review of cases admitted to the Pretoria Medico-Legal Laboratory, 2007-2011. Study conducted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Master's degree in Medical Criminalistics at the University of Pretoria) https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/30694/Barit_Medico_2013.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed 28 June 2019).

25 OHCHR, The Minnesota Protocol.

26 G Ruiz, T Wangmo, P Mutzenberg et al., Understanding death in custody: a case for a comprehensive definition, Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 11:3, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-014-9545-0. [ Links ]

27 Bhana, Custody-related deaths in Durban, South Africa.

28 C Goldstone, Police must shoot to kill, worry later - Cele, Independent Online, 1 August 2009, www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/police-must-shoot-to-killworry-later---cele-453587 (accessed 24 February 2019). [ Links ]

29 Bhana, Custody-related deaths in Durban, South Africa.

30 K King, Copped out, News24, 30 May 2011, www.news24.com/mynews24/yourstory/copped-out-20110530 (accessed 3 February 2019); South African Police Service, Roll of Honour, www.saps.gov.za/about/about.php (accessed 3 February 2019). .

31 B Kubat, W Duijst, R van de Langkruis et al., Dying in the arms of the Dutch governmental authorities, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 20:4, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2012.09.024; RV Bardale and PG Dixit, Suicide behind bars: a 10-year retrospective study, Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 57:1, 2015, https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.148531.

32 M Okoye, EH Kimmerle and K Reinhard, An analysis and report of custodial deaths in Nebraska, USA. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine 6:2, 1999, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1353-1131(99)90204-3. [ Links ]

33 CN Okoye, MI Okoye and DT Lynch, An analysis and report of custodial deaths in Nebraska, USA: Part II, Journal of Forensic and Lega Medicine, 19:8, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2012.04.008. [ Links ]

34 Wangmo et al., The investigation of deaths in custody

35 Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services, Annual Report 011/2012.