Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.64 Pretoria Jun. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2018/i64a4884

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Modest beginnings, high hopes. The Western Cape Police Ombudsman

Lukas Muntingh*

Co-founder and project coordinator of Africa Criminal Justice Reform (ACJR), formerly the Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative (CSPRI), as ACJR was known from 2003 until 2017. lmuntingh@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In 2013 the Western Cape legislature passed the Western Cape Community Safety Act (WCCSA) to improve monitoring of and oversight over the police. One creation of the WCCSA is the Western Cape Police Ombudsman, which became operational in 2015. This article reviews its history and context, as well as results from its first year. The Police Ombudsman, the only one in the country, must be seen as one of the results of efforts by the opposition-held province to carve out more powers in the narrowly defined constitutional space, and in so doing to exercise more effective oversight and monitoring of police performance, and improve police-community relations. The Ombudsman must also be seen against the backdrop of poor police-community relations in Cape Town and the subsequent establishment of a provincial commission of inquiry into the problem, a move that was opposed by the national government, contesting its constitutionality. Results from the Ombudsman's first 18 months in operation are modest, but there are promising signs. Nonetheless, the office is small and it did not do itself any favours by not complying with its legally mandated reporting requirements.

In South Africa, the powers that provincial governments hold over the South African Police Service (SAPS), a national competency, were reduced from what was contained in the Interim Constitution (1993) to the Constitution, which was promulgated in 1996.1 Under the Interim Constitution, the SAPS functioned 'under the direction of the national government as well as the various provincial governments',2 reflecting a dual responsibility with devolved authority. Provincial authority over the SAPS has now been reduced from provinces being responsible for 'directing' with national government, to the current situation which sees them with 'monitoring, overseeing and liaising' functions set out in section 206(3) of the Constitution. There is therefore a centralisation of authority in national government.

In 2009 the Democratic Alliance (DA) assumed power in the Western Cape, taking over from the African National Congress (ANC), making the Western Cape the only opposition-held province in the country. Since 2011 the Western Cape government has commenced with a number of initiatives to address crime and safety, such as provincial safety legislation and monitoring work done by the provincial department of community safety. These initiatives were aimed at improving the monitoring of police performance in order to bring about greater accountability and address the quality of policing. Specifically, these mechanisms have been aimed at exploring and utilising constitutionally mandated powers with reference to 'monitoring, overseeing and liaising functions', limited as they may be, with reference to the SAPS. The appointment of the Khayelitsha Commission in 2012 to investigate the breakdown of police-community relations in that township,3 and the passing of the Western Cape Community Safety Act4 (WCCSA) in 2013 were significant developments in this regard, and are seen as attempts to push back the centralised control over police performance.

The Khayelitsha Commission was established by the Premier of the Western Cape to investigate allegations of inefficiency at the three Khayelitsha police stations and allegations that there had been a breakdown in the relationship between the community and the police.5 The commission found that there were indeed a range of deep-seated problems relating to inefficiencies in the police, under-investigation of reported crimes and poor general management in the police, to name but a few. Dissatisfied with the quality of policing in the province, the provincial legislature passed the WCCSA to strengthen, among others, the provincial government's oversight role over the SAPS. In doing so it explored the limited space offered by the Constitution to strengthen police accountability and improve police performance in respect of crime and safety in the province.

The WCCSA created, among others, the Western Cape Police Ombudsman (Ombudsman), a complaints mechanism accessible to the general public that became operational at the end of 2015. It is the only one of its kind in the country. Evaluated against the history of police oversight in South Africa after 1994, this article investigates the establishment of the Ombudsman and its performance since its inception.

The establishment of an independent police investigative mechanism was a requirement set in the Interim Constitution6 and subsequently in the Constitution,7 and was operationalised by the SAPS Act of 1995 with the establishment of the Independent Complaints Directorate (ICD).8 The ICD was created before the 1996 Constitution was finalised and operational problems soon became evident. A review of the ICD was therefore necessary. An important contextual development occurred at national level in 2012 when the ICD metamorphosed into the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID),9 with a much more restricted scope. Although endowed with more powers, IPID was closed off as a general complaints mechanism, as it now focuses only on serious crimes implicating the police. Where the ICD could investigate 'any misconduct or offence allegedly committed' by a police official,10IPID is restricted to a list of serious offences.11Moreover, neither body's mandates dealt with police-community relations, an issue that became increasingly problematic in the Western Cape, as it was unclear where the public would go with less serious complaints. One possibility is the Civilian Secretariat for Police Services (CSPS), but the objects clause of its governing legislation excludes it from functioning as an explicit complaints mechanism, although it does have objects relating to stakeholder engagement and strengthening oversight.12Moreover, as an advisory body to the Minister of Police, it cannot be regarded as independent.

The Ombudsman's establishment should be seen as part of the Western Cape government's efforts to address crime and safety concerns. Crime and safety concerns in the Western Cape were, and continue to be, strongly influenced by the findings of the Khayelitsha Commission, which placed community-police relations and police inefficiency on centre stage. The case currently before the Equality Court, concerning the discrimination in the distribution of police resources against poor and black areas in Cape Town, is illustrative of this continuing focus,13as questions around the equitable allocation of police resources were a key finding from the Khayelitsha Commission.14

The following section provides more information on the policing context in the Western Cape, followed by a discussion of the legal framework that gave rise to the Ombudsman. This is followed by a description of the power of the Ombudsman and an evaluation of its performance since its establishment. The article concludes with an assessment of its future prospects and challenges.

Context of policing in the province

The Khayelitsha Commission clearly placed the quality of policing in the Western Cape on the political agenda. National government unsuccessfully attempted to block the establishment of the commission, first in the Cape High Court and later in the Constitutional Court.15 The establishment of the Khayelitsha Commission was preceded by numerous attempts by the Western Cape government, starting in November 2011, to engage the national government on a range of problems with policing in Khayelitsha as identified by a group of non-governmental organisations.16These efforts did not have the desired effect and in August 2012 the commission was appointed, although activities were delayed for nearly a year while the constitutional challenge brought by the Minister of Police was finalised.17While the litigation around the Khayelitsha Commission attracted significant attention, the passing, in April 2013, of the WCCSA took place with relatively little attention from the media and national government, although it was rumoured at one stage that this was also heading for the Constitutional Court with then Minister of Police, Nathi Mthethwa, threatening to challenge its constitutionality.18

The developments in the opposition-held Western Cape at provincial level as well as metro level must be viewed as an attempt by that provincial government to roll back the highly centralised nature of policing in the country.19Seen historically, the centralisation of policing was on the one hand motivated by a need to bring the various homeland police forces and the South African Police under central control, but also by a fear that regional militias and armies might arise out of the transition to democracy.20 In recent years there have also been calls from the ANC, and proposed as such in the White Paper on Policing, that the metro police services should also come under SAPS control; however, this proposal has met strong resistance.21

The Western Cape, and specifically the Cape Metropole, have a particularly serious violent crime problem. For example, from 2010 to 2016 murder increased by 47% and car hijacking by 382%.22 With the SAPS evidently failing to meet safety and security needs, the Western Cape government embarked on a different strategy by passing its own legislation from which community-based initiatives and new structures flowed, placing the emphasis on greater transparency and accountability through concerted monitoring. It is evident that the Western Cape's DA-led government is not satisfied with the quality of policing, and it has been progressive in exploring the legal avenues available to it in the Constitution. The establishment of the Khayelitsha Commission and the passing of the WCCSA are examples of these efforts. Another unique outflow of this process of constitutional exploration is the establishment of the Ombudsman.

Western Cape Constitution

The Western Cape Constitution came into effect on 16 January 1998 and granted the provincial government powers derived verbatim from the Constitution23 in respect of oversight over the police, namely:

-

To monitor police conduct

-

To assess the effectiveness of visible policing

-

To oversee the effectiveness and efficiency of the police service, including receiving reports on the police service

-

To promote good relations between the police and the community

-

To liaise with the national cabinet member responsible for policing with respect to crime and policing in the Western Cape

The Western Cape government may also investigate, or appoint a commission of inquiry into, any complaints of police inefficiency or a breakdown in relations between the police and any community; and must make recommendations to the national cabinet member responsible for policing.24 While the provincial government cannot instruct the police what to do, it can oversee and monitor performance with specific reference to police inefficiency and a breakdown in police-community relations, and bring this to the attention of the Minister of Police. Despite several provisions in the Constitution that facilitate cooperation between the national, provincial and local spheres of government,25it was indeed the failings of the relationship between the national and provincial spheres that gave rise to the establishment of the Khayelitsha Commission - a route borne out of frustration with the lack of cooperation between the two levels.

Western Cape Community Safety Act (Act 3 of 2013)

The notion of an Ombudsman is, of course, not new. Post-1994 the Constitution created the Office of the Public Protector, preceded by the Office of the Ombudsman established in 1991.26Other forms of this office have also come into being domestically in the private sector (e.g. Short Term Insurance Ombudsman)27 as well as other cross-cutting spheres (e.g. Health Ombudsman).28 There is also no universal definition of what an Ombudsman is, but Carl, in her taxonomy of public sector ombudsman institutions, proposes the following:

An ombudsman is a public sector institution which, for the purpose of the protection of individual rights and the defence of the fundamental rights of democracy such as civil and human rights, is authorized by a parliament, a ministry or a subdivision thereof (legal foundation) to investigate independently both own-motion as well as complaints from citizens about an alleged part of the administration's/executive's acts, omissions, improprieties, and broader systemic problems, and whose only tools - due to not being invested with any executive power - are its own personal authority, recommendations, annual and special reports and the media.29

Section 67(1) of the Western Cape Constitution empowers the province to pass any legislation to carry out the functions listed in section 66(1) of the Constitution, which include the police monitoring and related functions. Section 3 of the WCCSA mandates the provincial Minister for Community Safety to exercise a fairly broad range of powers centring on three main foci: monitoring police performance; overseeing the effectiveness and efficiency of the police; and building good relations between the police and other stakeholders. Section 3(l) of the WCCSA mandates the provincial Minister to 'record complaints relating to police inefficiency or a breakdown of relations between the police and the community'. The recording of complaints is understood to fall under the provincial Minister's broader mandate to build good relations between the police and the community, although it may equally be regarded as part of its monitoring function. It is consequently section 3(l) of the WCCSA, read with sections 66(1) and 67(1) of the Western Cape Constitution, that gave rise to the Ombudsman. Even though the creation in law of the Ombudsman preceded the Khayelitsha Commission finalising its work, there was already sufficient information in the public domain on poor police-community relations and police inefficiencies to justify its creation.

The Ombudsman in the WCCSA

The WCCSA mandates the Premier to appoint the Ombudsman after consultation with the provincial Minister, the Provincial Commissioner of Police and the executive heads of municipal police services. The appointment is further subject to approval by the provincial parliament's standing committee responsible for community safety by a resolution adopted in accordance with its rules.30 The only requirement is that the Ombudsman must be a suitably qualified person with experience in law or policing. Unlike the Public Protector, the Ombudsman does not need a minimum number of years of experience or have specified qualifications.31The Ombudsman is further appointed for a non-renewable term of five years. The Premier may remove the Ombudsman from office for good cause after consultation with the provincial Minister, the Provincial Commissioner of Police and the executive heads of municipal police services. Again, this is subject to approval by the provincial parliament's standing committee responsible for community safety by a resolution adopted in accordance with its rules. The committee may recommend the removal of the Ombudsman from office on the grounds of misbehaviour, incapacity or incompetence, after affording him or her a reasonable opportunity to be heard.32 The Ombudsman and staff members of the office are also obliged to serve independently and impartially, and perform their functions without fear, favour or prejudice.33The Ombudsman's budget is voted on by the provincial parliament as part of the budget of the Department of Community Safety.34Being part of the departmental budget may impact on the Ombudsman's independence, as has been noted in respect of the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services.35 The difference is, however, that the Ombudsman does not oversee the department it receives its budget from, but is instead funded through a department that is part of the monitoring and oversight architecture over the SAPS in the province. The Ombudsman may also be assisted by a person whose service the Ombudsman requires for the purpose of a particular investigation.36 The first Ombudsman, Adv. Vusi Pikoli, was appointed on 1 December 2014 and 2015/16 was its first full financial year, during which it was allocated a budget of just below R7 million.37

Powers of the Ombudsman

The central function of the Ombudsman is to 'receive and ... investigate complaints submitted in terms of section 16, regarding inefficiency of the police or a breakdown in relations between the police and any community'.38 It is therefore a reactive mechanism and does not have the power to investigate of its own volition, unlike the Inspecting Judge for Correctional Services39or the Public Protector.40 In order to resolve a complaint, if it is not manifestly frivolous, the Ombudsman has a number of avenues open to him or her. The first, and assuming there is sufficient information, is to refer the complaint to a more appropriate and competent authority, which may be a national authority, community-policing forum (CPF), a constitutional authority or provincial authority. Second, if the complaint is deemed to be of a serious nature or it may be dealt with more appropriately by a commission of inquiry, a recommendation to this effect may be made to the Premier. Third, the Ombudsman may decide to investigate the complaint.41In order to conduct an investigation, the Act affords the Ombudsman two broad powers established under section 18 of the Act:42

18(1) The Ombudsman may direct any person to submit an affidavit or affirmed declaration or to appear before him or her to give evidence or to produce any document in that person's possession or under his or her control which has a bearing on the matter being investigated, and may question that person thereon.

18(2) The Ombudsman may request an explanation from any person whom he or she reasonably suspects of having information which has a bearing on the matter being investigated or to be investigated.

The regulations to the Act bolster these powers further by adding that the Ombudsman may have meetings with affected persons who may have information relevant to the complaint; conduct research; conduct inspections in loco; and administer surveys.43 Further, the regulations also provide that the Ombudsman may engage in negotiations and conciliation if necessary.44 Unlike a judicial commission of inquiry (e.g. the Khayelitsha Commission) the Ombudsman does not have the explicit power to subpoena, and a number of mechanisms are included to ensure cooperation. The strongest of these is the provision that if a person fails to cooperate, fails to answer questions, provides false information, or hinders or obstructs the Ombudsman's investigation, such a person is guilty of an offence and liable to a fine or imprisonment for a period of up to three years.45Further, failure by a police official or any other state official to cooperate must be reported to the Provincial Commissioner, executive head of the relevant municipal police, as the case may be, and the provincial Minister.46If, upon completion of an investigation, the matter cannot be resolved, the Ombudsman must submit his recommendation to the provincial Minister and inform the complainant accordingly. The provincial Minister must make a recommendation to the Minister of Police on any investigated complaints that could not be resolved by the Ombudsman, and inform the complainant accordingly.47

It is apparent that the recommendations from the Ombudsman do not have binding power on the provincial commissioner, as there is no constitutional basis for such power and the provincial commissioner takes instruction from the national commissioner and not the provincial government. The Ombudsman also does not have remedial powers, unlike the Public Protector.48 This is, however, not to say that the recommendations of the Ombudsman are without power or authority. That power is not in a direct relationship with the provincial commissioner, but rather through the provincial Minister and ultimately the provincial parliament. The provincial Minister must make a recommendation to the national Minister on investigated complaints that could not be resolved by the Ombudsman.49

The provincial legislature and executive therefore hold considerable authority over the provincial commissioner once it becomes apparent that recommendations from the Ombudsman are ignored or good reasons are not provided for not implementing them. The provincial commissioner must, on a regular basis, report to the provincial parliament on a number of predetermined issues, as well as on any other matter that the provincial parliament may request.50 It should further be borne in mind that the provincial commissioner is appointed by the national commissioner with the concurrence of the provincial executive, and a special relationship therefore exists between the two parties.51 It is therefore indeed possible that the provincial parliament can place significant pressure on the provincial commissioner. Read together, the Constitution, Western Cape Constitution and the WCCSA provide for the provincial parliament, if it has lost confidence in the provincial commissioner, to call him or her to appear before it or any of its committees, prior to starting disciplinary action or proceedings for his or her dismissal or transfer.52

In an opposition-held province, the provincial executive and legislature are far more likely to thoroughly utilise this oversight function to bring about an improvement in crime and safety, and the Ombudsman forms part of this dispensation. For example, by 2016 the provincial Department of Community Safety was monitoring 25 courts in order to identify police inefficiencies in criminal investigations and docket management.53 The Department of Community Safety has also established a police complaints centre to deal with service delivery complaints - a further initiative to deal with poor police community relations and improve accountability.54 That the Western Cape has moved in this direction and has brought oversight to provincial level through law reform is at least in part motivated by frustration with the current centralised nature of policing, where the Western Cape provincial Minister of Community Safety has to compete with eight other provincial ministers for the national Minister's ear at Ministers and Members of Executive Councils (MINMEC) meetings.55 Crime and safety in the Western Cape has certain unique features (e.g. gangsterism on the Cape Flats) and requires a more tailored response from the SAPS, but that has not been forthcoming in recent years. The Ombudsman's power and authority is therefore

highly dependent on an effective provincial government taking its oversight responsibilities seriously. A provincial government that is tardy in overseeing the police would probably render the Ombudsman obsolete. Should the Western Cape revert to ANC control, it may hold significant consequences for police oversight and monitoring, including the role and authority of the Ombudsman. The current situation of natural tension between the national government and an opposition-held province, a result of normal democratic processes, is indeed beneficial for police accountability.

Achievements and performance

The WCCSA requires the Ombudsman to report annually to the MEC on the number of complaints investigated; the number of complaints determined to be manifestly frivolous or vexatious; the outcome of investigations into the complaints; and the recommendations regarding the investigated complaints.56 According to its annual report, from 1 December 2014 until the end of the 2015/16 financial year, the Ombudsman received 399 complaints across seven categories as indicated in Figure 1, with 'unacceptable behaviour' being the highest at 114 complaints. The annual report does not define or give examples of 'unacceptable behaviour'. Figure 2 shows the number of complaints received per month from January 2015 to March 2016, indicating a steady increase in the number of complaints received over the period.

This data points to modest beginnings indeed, if we bear in mind there are 150 police stations in the province, 18 020 police officials,57 and a population of 6.2 million people.58

As noted already, the Ombudsman received 399 complaints in its first year and the actions taken on these are reflected in Table 1.59 Nearly 80% of complaints were investigated, but only 17% resulted in a report. This may be a result of investigations taking unexpectedly long, which may mean that some cases will be carried forward to (and reported on in) the next financial year. The Ombudsman's report notes that some complaints are dealt with in a matter of days but that others require lengthy investigation in order to understand the 'intricacies associated with complex issues'.60 The Ombudsman's office has a small staff and only four people are dedicated to investigations. This, combined with being a new institution that is in the process of establishing its work methods, may have further contributed to the low proportion of reports produced.

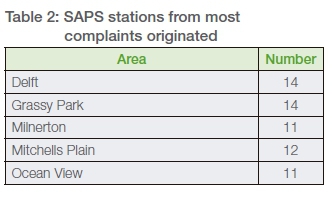

Complaints originated from all over the province, but the top five areas of origin are given in Table 2. It should be noted that in 20 complaints the area of origin was unknown. It is nonetheless encouraging that four of the five areas listed in Table 2 are in crime-ridden and impoverished Cape Flats communities, indicating that there is some measure of trust in the Office of the Ombudsman.

What seems to be lacking from the annual report is data giving insight into the impact of the Ombudsman; information that would reflect in some way whether complaints investigations and reports made by the Ombudsman have improved police-community relations, and if there has been a change in police performance. No information is provided on how complaints were resolved, the nature of recommendations made to the SAPS, and what the SAPS's reaction to these complaints was. This lack of detail is regrettable as such information may give insight into the effectiveness of the Ombudsman. As noted above, the WCCSA requires that the Ombudsman must report in its annual report on the activities under its mandate, including the number of investigations, their outcome, and the recommendations made to the SAPS.61None of these requirements was met in the 2015/2016 annual report. Subsequent annual reports should reflect more closely on steps taken by the Ombudsman to improve police-community relations and, more specifically, on how the police have responded and if the responses had the desired effect.

Conclusion

The Western Cape, through the WCCSA, is pushing for a stronger oversight relationship with the SAPS, even though its powers are significantly curtailed by the Constitution. Nonetheless, it is attempting to make policing more closely aligned to the needs of the Western Cape and to hold the police accountable to the extent possible under the Constitution. National government was resistant to the Western Cape's appointment of a commission of inquiry into police-community relations, and made this very clear in its opposition to the Khayelitsha Commission. While there may have been talk of similar opposition to the WCCSA, this did not materialise and the Constitutional Court has now affirmed that provincial governments have a legitimate interest in improved policing, and that they can engage in a range of functions towards this end, including establishing judicial commissions of inquiry. The Constitutional Court did not deal with the Ombudsman in the Khayelitsha Commission case, as it was not raised by either party, but since national government has not publicly opposed it and the office was established, we can conclude that it is now an accepted part of the Western Cape oversight architecture and the devolution of power.

Whether other provinces will embark on a similar route is probably unlikely as long as they are controlled by the same political party that controls national government. However, it is safe to conclude that policing needs vary across the provinces and also at local level, and for this reason it is necessary to devolve oversight accordingly. Even if such oversight has a limited mandate, it should contribute to addressing current poor police-community relations and bring about more accountable and responsive policing. The other provinces will therefore be wise to monitor how the Western Cape approach unfolds over the next three to fwe years.

The Ombudsman faces a number of significant challenges and this should temper expectations as to its impact. The office has a tiny budget at this stage (some R7 million) and this has implications for its capacity to investigate, as well as its accessibility to the province's population. The provincial government may review its allocation if there is evidence of a high demand for its services and that the Ombudsman is effective in fulfilling its mandate when intervening. A further challenge for the Ombudsman is its limited powers regarding police conduct. The Ombudsman's recommendations are not binding, and thus it has to rely on moral authority and the powers of persuasion. Fortunately, the Ombudsman can rely on the provincial executive as well as the provincial legislature to apply pressure on the police to improve performance, although this reliance may be tempered if the political dispensation reverts to an ANC-controlled province.

With only one office in Cape Town, the Ombudsman will have to do a fair amount of promotional work to inform the public of its functions, and also to report on successes in order to build confidence in its independence and effectiveness in addressing poor policing and poor police-community relations. We know very little about how the police regard the Ombudsman and its recommendations, but it is safe to predict that the relationship will likely be strained and that the police will be resistant to implementing its recommendations.

The Ombudsman will need the support of the executive to make headway in this regard. However, if the SAPS can see the benefits of the Ombudsman's interventions, this will surely foster stronger cooperation.

Notes

* He holds a PhD (Law) from UWC and an MA (Sociology) from Stellenbosch University. He has been involved in criminal justice reform since 1992 and has worked in Southern and East Africa on child justice, prisoners' rights, preventing corruption in the prison system, the prevention and combating of torture, and monitoring legislative compliance. His current focus is on the prevention and combating of torture and ill-treatment of prisoners and detainees.

1 Ex parte Chairperson of the Constitutional Assembly: In re Certification of the Amended Text of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 [1996] ZACC 24; 1997 (2) SA 97 (CC); 1997 (1) BCLR 1 (CC) (Second Certification Case), para 448; Minister of Police and Others v Premier of the Western Cape and Others (CCT 13/13) [2013] ZACC 33; 2013 (12) BCLR 1365 (CC); 2014 (1) SA 1 (CC), para 35-36.

2 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1993 (Act 200 of 1993), section 214(1); Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 (Act 108 of 1996).

3 Khayelitsha is a partially informal settlement in Cape Town (Western Cape) with a population of some 400 000 people, according to the 2011 census. The population is mainly isiXhosa speaking and socio-economic deprivation is severe.

4 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013 (Act 3 of 2013).

5 Khayelitsha Commission, Towards a safer Khayelitsha: report of Commission of Inquiry into allegations of police inefficiency and a breakdown in relations between SAPS and the community in Khayelitsha, 2014, http://www.khayelitshacommission.org.za/images/towards_khaye_docs/ Khayelitsha_Commission_Report_WEB_FULL_TEXT_C.pdf (accessed 13 June 2018).

6 Interim Constitution 1993, section 222.

7 Constitution 1996, section 206(6).

8 South African Police Service (SAPS) Act 1995 (Act 68 of 1995), chapter 10.

9 D Bruce, Strengthening the independence of the Independent Police Investigative Directorate, African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF), Policy Paper, 2017, 4. [ Links ]

10 SAPS Act, section 53(2).

11 Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) Act (Act 1 of 2011), section 28(1): '(a) any deaths in police custody; (b) deaths as a result of police actions; (c) any complaint relating to the discharge of an official firearm by any police officer; (d) rape by a police officer, whether the police officer is on or off duty; (e) rape of any person while that person is in police custody; (f) any complaint of torture or assault against a police officer in the execution of his or her duties; (g) corruption matters within the police initiated by the Executive Director on his or her own, or after the receipt of a complaint from a member of the public, or referred to the Directorate by the Minister, an MEC or the Secretary, as the case may be; and (h) any other matter referred to it as a result of a decision by the Executive Director, or if so requested by the Minister, an MEC or the Secretary as the case may be, in the prescribed manner. (2) The Directorate may investigate matters relating to systemic corruption involving the police.'

12 Civilian Secretariat for Police Act (Act 2 of 2011), section 5.

13 Social Justice Coalition, Police Resources court case resumes 14 & 15 February in Equality Court, 13 February 2018, https://www.sjc.org.za/police_resources_court_case_resumes_14_15_february_in_ equality_court (accessed 13 June 2018); Khayelitsha Commission, Towards a safer Khayelitsha.

14 Khayelitsha Commission, Towards a safer Khayelitsha, 449.

15 Minister of Police and Others v Premier of the Western Cape and Others, para 35-36.

16 Khayelitsha Commission, Towards a safer Khayelitsha, 2.

17 Ibid., xxii.

18 J de Visser, The W Cape Community Safety Act: is Zille pushing her luck?, Politicsweb, 13 May 2013, http://www.politicsweb.co.za/news-and-analysis/the-wcape-community-safety-act-is-zille-pushing-he (accessed 13 June 2018).

19 N Steytler and L Muntingh, Meeting the public security crisis in South Africa: centralising and decentralising forces at play, in Law and justice at the dawn of the 21st century: essays in honour of Lovell Fernandez, Bellville: Faculty of Law, University of the Western Cape, 2016, 85. [ Links ]

20 Ibid., 85.

21 D Bruce, ANC no longer 'needs' a single police force, Mail & Guardian, 15 February 2013, https://mg.co.za/article/2013-02-15-00-anc-no-longer-needs-a-single-police-force (accessed 13 June 2018); [ Links ] Civilian Secretariat for Police, White Paper on Policing in South Africa, 2016, 29, http://www.policesecretariat.gov.za/downloads/bills/2016_White_Paper_ on_Policing.pdf (accessed 13 June 2018).

22 Institute for Security Studies (ISS) Crime Hub, Provincial crime, https://issafrica.org/crimehub/facts-and-figures/provincial-crime (accessed 13 June 2018).

23 Constitution 1996, section 206 (3 and 5). See also Constitution 1996, schedule 4 - Concurrent functionalities: 'Police to the extent that the provisions of Chapter 11 of the Constitution confer upon the provincial legislatures legislative competence'.

24 Ibid., section 206(5).

25 Ibid., section 205 (1): 'The national police service must be structured to function in the national, provincial and, where appropriate, local spheres of government. (2) National legislation must establish the powers and functions of the police service and must enable the police service to discharge its responsibilities effectively, taking into account the requirements of the provinces'; ibid., section 206 (1) 1: 'A member of the Cabinet must be responsible for policing and must determine national policing policy after consulting the provincial governments and taking into account the policing needs and priorities of the provinces as determined by the provincial executives. (2) The national policing policy may make provision for different policies in respect of different provinces after taking into account the policing needs and priorities of these provinces.'

26 South African History Online, The office of the Public Protector 1995, http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/office-public-protector-1995 (accessed 3 April 2018).

27 The Ombudsman for Short-Term Insurance, http://www.osti.co.za/ (accessed 3 April 2018).

28 Health Professions Council of South Africa, Office of the Ombudsman, http://www.hpcsa.co.za/OrgStructure/OmbudsmanOffice (accessed 3 April 2018).

29 S Carl, Toward a definition and taxonomy of public sector ombudsmen, Canadian Public Administration, 55:2, 2012, 214.

30 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 11(2).

31 Public Protector Act 1994 (Act 23 of 1994), section 1A(3).

32 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 6(a).

33 Ibid., section 15(a).

34 Ibid., section 12.

35 L Muntingh and C Ballard, CSPRI submission on the strengthening of the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services, Bellville: Civil Society Prison Reform Initiative (CSPRI), 2012.

36 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 11(7).

37 Office of the Western Cape Police Ombudsman, Annua report 2015-16, https://www.westerncape.gov.za/police-ombudsman/files/atoms/files/WCPO_AR%20for%2015_16_FINAL.pdf (accessed 3 April 2018).

38 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, sections 15-16.

39 Correctional Services Act 1998 (Act 111 of 1998), section 90(2).

40 Public Protector Act 1994, section 6.

41 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 17.

42 Ibid., section 18.

43 Ibid., regulation 8.

44 Ibid., regulation 14(c).

45 Ibid., section 30(1).

46 Ibid., regulation 7(8).

47 Ibid, section 17(8).

48 Constitution 1996, section 182(1)(c); Economic Freedom Fighters v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others; Democratic Alliance v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others (CCT 143/15; CCT 171/15) [2016] ZACC 11; 2016 (5) BCLR 618 (CC); 2016 (3) SA 580 (CC) (31 March 2016).

49 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 17(8).

50 Ibid., section 19.

51 Constitution 1996, section 207(3).

52 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, sections 19(6), 20; Western Cape Constitution, section 69(2); Constitution 1996, 207(6).

53 EWN, 'WC govt wants to intensify oversight over police', 19 February 2016, http://ewn.co.za/2016/02/22/WC-govt-wants-to-intensify-oversight-over-police (accessed 13 June 2018).

54 Western Cape Government, Policing Complaints Centre, https://www.westerncape.gov.za/service/policing-complaints-centre (accessed 13 June 2018).

55 Steytler and Muntingh, Meeting the public security crisis in South Africa, 85.

56 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 13(1).

57 Socia Justice Coalition and Others v Minister of Police and Others, EC 03/2016.

58 Statistics South Africa, Mid-year population estimates 2016 (Statistical release P0302), 16, https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022016.pdf (accessed 13 June 2018).

59 Office of Western Cape Police Ombudsman, Annual report 2015-16, 39.

60 Ibid., 37.

61 Western Cape Community Safety Act 2013, section 13 (1) (b-d).