Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.63 Pretoria Mar. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2018/v0n63a3028

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Mass killings and calculated measures: The impact of police massacres on police reform in South Africa

Guy Lamb

Director of the Safety and Violence Initiative (SaVI) at the University of Cape Town. guy.lamb@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Over the past two centuries, the police have perpetrated massacres in response to protest action in numerous countries. Available scholarly literature has typically focused on the circumstances that contributed to such mass killings, but rarely has there been consideration of the impact that such massacres subsequently may have had on the police organisation. Hence, this article will explore the relationship between massacres perpetrated by the police and police reform, with a particular focus on South Africa. The article concludes that, in the context of public order policing, massacres perpetuated by the police can contribute towards relatively immediate police reforms, particularly in terms of police strategies and tactics. In some circumstances, massacres have even led to some restructuring of the police organisation. The nature of the government and the policing environment appeared to be key determinants of the types of police reforms, post-massacre.

In August 1819, 17 people were killed and hundreds were injured during a protest for parliamentary reform at St Peter's Fields in Manchester, England, as a result of a cavalry charge by the sabre-wielding yeomanry. This incident has commonly become known as the 'Peterloo Massacre' and, as many policing scholars have argued, was an important event in the founding of the modern police. This massacre underscored for parliamentarians as well as the ruling elite that military troops were an inappropriate mechanism for the policing of protests, and ultimately contributed to the creation of the civilian-oriented London Metropolitan Police in 1829.1 This police model was gradually adopted by numerous states and has now become one of the more prevalent police models in most democratic contexts.

Over the past two centuries the police have perpetuated massacres in response to protest action in many countries, such as Brazil, Ethiopia, France, Peru, the Philippines, South Africa, Ukraine, the United States and Yemen (to name but a few). A police massacre is in essence a specific incident that entails the indiscriminate killing of a large number of people by an official government police entity. Scholarly literature has typically focused on the circumstances that contributed to such mass killings, but rarely has there been consideration of the impact that such massacres may subsequently have had on police organisations. This is somewhat surprising, given the key role that a massacre played in the establishment of the modern police model. This article therefore explores the relationship between massacres perpetrated by the police and police reform, with a particular focus on South Africa.

In the policing literature reform is typically associated with the refashioning of the police with a view to forging more democratic approaches to policing.2 However, this article, drawing on the work of Styles,3 makes use of a broader definition of police reform, namely changes that are made to the police with the aim of improving police work and the functioning of the police organisation for all government types, not only democracies. Under this definition, police reform can, in effect, entail the adoption of more repressive policing methods and can include the acquisition of military-style equipment in the context of an authoritarian regime, as such reforms are typically geared towards improving the regime's prospects of maintaining its oppressive rule and authority.

Using this broader conceptualisation of police reform, this article will address the following research question: what types of police reforms in South Africa were implemented after major massacres perpetrated by the police, and why? The article will analyse the relationship between various prominent massacres perpetrated by the police in South Africa between 1920 and 2012, and the subsequent police reforms (or the lack thereof).

Massacres and police reforms

A reading of published police histories from a variety of countries suggests that there is a conceivable relationship between massacres perpetrated and reforms implemented by the police. What is evident, however, is that the context and nature of each massacre was key to determining whether or not police reforms would be pursued in its aftermath. In essence, five propositions can be derived from the literature, as outlined below.

Firstly, the police will adopt reforms where massacres result in significant injuries and casualties to the police, or where they realise that such forceful tactics may contribute to more large-scale protests. This was the case with the Haymarket riot in Chicago in 1886, where a bomb was hurled at the police during a militant labour demonstration. Four protestors and seven policemen were killed in the ensuing events. Thereafter the police altered their tactics and engaged in undercover operations in order to pre-empt further violent confrontations with protestors. Two years later, the Chicago police declared that the lesson they had learned from such changes to policing tactics was that 'the revolutionary movement must be carefully observed and crushed if it showed signs of growth'.4 A more recent example took place in Zhanaozen, Kazakhstan, where the police reportedly adopted less lethal approaches to public order policing after their violent crackdown on striking oil workers in 2011 resulted in the death of 15 strikers. These changes were based on concerns that further police repression might lead to a surge in anti-government agitation.5

Secondly, the police will initiate a reform process following a massacre where they perceive that they were unprepared for the protest encounter and overwhelmed by the protestors. This has mainly been the case where repressive governments have changed policing strategies and tactics following a massacre in an attempt to contain and quash further protest action that could ultimately result in the demise of the authoritarian regime. For example, in 2005 the Ethiopian police, who had a history of extensive human rights abuses,6 massacred close to 200 protesters and injured more than 700, following contested election results.7 Following this massacre, the Ethiopian police reportedly received considerable military-style riot control training from the South African Police Service (SAPS), and purchased significant amounts of more modern riot control equipment and weaponry.8 Furthermore, the Ethiopian police sought to forge more effective relationships with communities in order to 'strengthen support for the police and to further the gathering of intelligence'.9

Thirdly, there will be no apparent police reforms after a massacre in cases where the protestors did not pose a significant threat, or did not inflict significant casualties on the police, and there was no political will to hold the police to account for their actions. A clear example was the massacre of approximately 200 protestors of North African descent by the Paris police in 1961, which was during the time of the Algerian civil war.10 There were no indications that the Paris police underwent any significant changes thereafter, other than the intensification of intelligence-gathering activities in relation to dissident groups.11 A further example was the 1987 Mendiola Massacre in the Philippines where the police killed 13 people who were protesting for agrarian reform. There were no police casualties, and no immediate police reform, despite a government-wide process of democratisation.12 There were similar dynamics after a massacre in the Malaysian village of Memali in November 1985, where police killed 14 members of an Islamic sect.13

Fourthly, police reform will be pursued after massacres have taken place in the context of regime change such as a transition to democratic rule, where the police had previously been responsible for the excessive use of violence against civilians (including massacres). Examples here include Chile, Indonesia, Namibia and South Africa. In some instances, as with Ukraine, a massacre by police was the catalyst for more immediate changes in policing. In this case the Ukrainian 'Berkut' riot police were disbanded because they shot unarmed demonstrators during anti-government protests in Kiev in 2014. This was part of a larger police reform process that was pursued after the ousting of the Yanukovych government.14

Fifthly, democratic police reforms towards the use of less repressive measures following a massacre are only likely where there have been concerted efforts by governments to implement a reform process. This is because the police as an institution are acutely resistant to change, and resolute external pressure is therefore often required to compel the police towards reform.15For example, in Mexico, following the massacre of 43 students in Iguala in September 2014 by an organised criminal group (these students had previously been abducted by corrupt police and then handed over to the criminal group), the government initiated a legislative police reform process, focusing in particular on the municipal level. However, to date this process has been undermined by political wrangling.16

These five propositions will be used in the following sections as the basis to further examine the nature of the relationship between massacres and police reforms in South Africa since the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The focus will be on the key massacres that were perpetrated by the police in the 1920s; the Sharpeville massacre (1960); the Soweto uprising (1976); massacres that took place during the mid to late 1980s; and the Marikana massacre (2012).

Public order policing in South Africa: a brief historical overview

Between 1910 and 1993 the South African Police (SAP) generally resorted to the use of force (or the threat thereof) in order to disperse and quell agitated crowds of black people. This was motivated by concerns that localised protest action could rapidly escalate into more widespread collective disorder in other black communities, which in turn could spill over geo-racial urban boundaries and threaten the apartheid status quo. Militant strike action by white mine workers in 1921/22 also resulted in a repressive police response, fuelled by concerns that such protests would significantly undermine the mining industry, which was a key component of the South African economy.17

The SAP typically policed protests in townships at arm's length, using an arsenal of military-style vehicles and incapacitants (such as tear gas). If required, SAP members would engage in a baton charge and use sjamboks on protestors. Lethal force (including live ammunition) was applied on those occasions where protestors breached the SAP buffer zone, or if the crowd did not adhere to instructions from the police.18However, as will be shown below, there were a number of occasions where the SAP was unprepared for the intensity of public protests and organised defiance, which resulted in the police injudiciously using excessive lethal force in an effort to repel and disperse protestors. Frequently, large numbers of protestors died as a result.

There was a series of militarised reforms to public order policing in the 1980s and early 1990s, which will be discussed in more detail in the sections below. Substantial efforts were made to reform the police after the 1994 democratic elections, which included the restructuring of public order policing.

Port Elizabeth (1920) and the Bulhoek massacre (1921)

In the early 1920s the SAP used excessive force against a series of strikes and uprisings by black South Africans so as to enforce racial and class segregation and to ensure that these incidents of protest did not result in more widespread insurrection and disruption to the economy.

In at least two such confrontations police personnel massacred black protestors in the Eastern Cape, namely in Port Elizabeth and Bulhoek.

In October 1920, in the midst of a militant strike instigated by a faction of the Port Elizabeth Industrial and Commercial Workers' (Amalgamated) Union of Africa, a combined force of police and deputised white civilians opened fire on unarmed black protestors outside a police station in Port Elizabeth. Some 24 black protestors were killed. The shooting resulted in rapid dispersal of the protestors,19and there were no police casualties. Prior to this massacre there had been general anxiety among white residents, not only in Port Elizabeth but also countrywide, that the strike would rapidly escalate into widespread violence with black mobs attacking white homes and businesses. According to the Inspector of Labour, W Ludorf:

[U]nless prompt action had been taken, Port Elizabeth would have been in the throes of something too awful to contemplate ... in my considered opinion the prompt action taken in firing is fully justified and quelled a very serious native revolt against constituted authority.20

In 1921 the SAP, in conjunction with the military, used overwhelming force to suppress an uprising in Bulhoek near Queenstown. In this instance, a contingent of around 800 policemen opened fire on members of a religious sect, the 'Israelites', who were armed with swords and assegais and were illegally occupying government land. Previous attempts by government authorities to disperse the squatters through negotiation and threat of force had failed.21 A military-style police action was subsequently mounted, which led to the massacre of approximately 200 cult members, with more than 100 others wounded.22

In line with the third proposition (that there will be no apparent police reforms after a massacre in cases where the protestors did not pose a significant threat) no noticeable police reforms were pursued in the aftermath of these two massacres. This was most likely because the protesting groups did not pose a significant threat to the police, who, with their superior firepower, were easily able to quash the protest actions. Furthermore, the risk of these two protests, igniting unrest in other areas of South Africa was relatively low at the time.

Sharpeville massacre (1960)

In March 1960, in the township of Sharpeville near Vereeniging, approximately 300 police opened fire on a crowd of thousands of Pan Africanist Congress supporters who were protesting against the pass system, killing 69 and injuring approximately 180 people. Firsthand accounts of the massacre suggest that the policemen on the scene, feeling overwhelmed and fearful, opened fire on the protestors in a state of agitation.23 This incident was a wake-up call for government, who realised that black communities had become less compliant with apartheid regulations and policing techniques, and that more organised anti-apartheid opposition had developed in a number of townships.24 During parliamentary debates immediately following the massacre, De Villiers Graaff, the leader of the opposition party at the time, expressed concern that in townships where there had been unrest, 'agitators were receiving more support from natives who were usually law abiding'.25

By 1961, as a direct result of the Sharpeville massacre, and in line with the second proposition (that the police will initiate a reform process following a massacre where they perceive that they were unprepared for the protest encounter) there were significant organisational changes within the SAP. The number of white policemen in the force was increased substantially, and the Reserve Police Force (a part-time citizen force) was created.26

Additional funds were allocated to the SAP to procure the 'most modern equipment in order to crush any threat to internal security successfully'.27 There was also a reconfiguration of the SAP's territorial policing boundaries, with the SAP's administrative geographical divisions being reconfigured to allow for more effective collaboration with the South African Defence Force (SADF). A government committee was subsequently established to reform police training in order 'to ensure that police constables in the future will be better equipped for their task both physically and mentally and will have better knowledge of their exacting duties'.28

Furthermore, in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre, the size and budget of the security branch within the SAP increased considerably.29From the early 1960s the security branch sought to disrupt the activities of anti-apartheid groups and liberation movements by capturing or neutralising their leaders and operatives. In order to achieve this the security branch required actionable intelligence, which was generated through a large network of informers, the infiltration of anti-apartheid movements and the extensive use of detention, harsh interrogation and torture of suspected anti-government activists.30 Furthermore, from the early 1960s, the security branch used interrogation and torture in order to 'turn' certain captured insurgents into informers (known as askaris) who could infiltrate the liberation movements.31

Soweto uprising (1976)

In June 1976, approximately 10 000 school learners and adults took to the streets of Soweto outside Johannesburg to protest against the government's requirement that Afrikaans be used as a mandatory medium of instruction in schools. Confrontations between the riot police and the protestors rapidly escalated and culminated in the police fatally shooting more than 400 demonstrators and injuring approximately 3 000.32 Shortly thereafter, violent protests erupted in townships on the East Rand and in Cape Town, which the SAP, with the support of the SADF, forcefully subdued.33In total, the SAP discharged in the region of 50 000 rounds of ammunition against protestors in all areas during the various uprisings at the time.34

Providing feedback to Parliament on the Soweto violence, Jimmy Kruger, the cabinet minister responsible for the police, stated that policemen had opened fire in 'self-defence', as they felt that they were 'overwhelmed' and that 'their lives were in grave danger'.35 The findings of the Cillié Commission of Inquiry36 into the causes of the Soweto uprising emphasised that the police on the scene were in imminent danger, and that the lethal actions of the SAP members were justified. The reasons given were that the policemen on the scene were significantly outnumbered by the protestors, who had thrown stones at the police, and had surrounded the police after less lethal attempts to disperse the protestors had failed. There were extensive references to the written statement by Sergeant MJ Hattingh, one of the policemen who had fired on the protestors. According to the commission report:

He [Sergeant Hattingh] saw that other members of the squad had been injured, some seriously, and it was clear to him that the crowd was going to overpower them. He was hit on the leg by a stone and fell down on the ground ... he heard others firing ... He got up and drew his firearm. A black man charged at him with a brick in his left hand and a kierie [stick] in his right hand. To beat off the attack, he fired straight at the man. The attacker fell down dead ... he fired five more shots at the legs of the charging crowd.37

The report further recounts that Hattingh was able to retreat to his police vehicle, but was subsequently surrounded by a group of protestors:

They [the protestors] tried to drag him out of the vehicle, grabbed his cap and ripped the badges from his uniform. His hand was injured by a sharp object and an attempt was made to take his firearm from him. Col. Kleingeld [the commanding officer on the scene] drove the attackers off with bursts from the automatic rifle, and the sergeant and his vehicle were removed from the danger area.38

Critically, the commission concluded that the hazardous situation in which the police found themselves was also largely the result of the SAP personnel on the scene being ill prepared and not sufficiently competent to effectively disperse such a large group of protestors. Hence, of direct relevance to the second proposition (that police reforms take place after a massacre where the police are of the view that they had been unprepared or overwhelmed by the protestors), the SAP's public order policing capability was significantly improved at station level in the years immediately after the Soweto uprising, and the riot control function of the police was centralised into a riot control unit.39Furthermore, the SADF were tasked to support the SAP in crowd control incidents, based on the view that a display of overwhelming force would prompt protesting crowds to disperse without violent confrontation.40

Policing under a state of emergency: 1984-1989

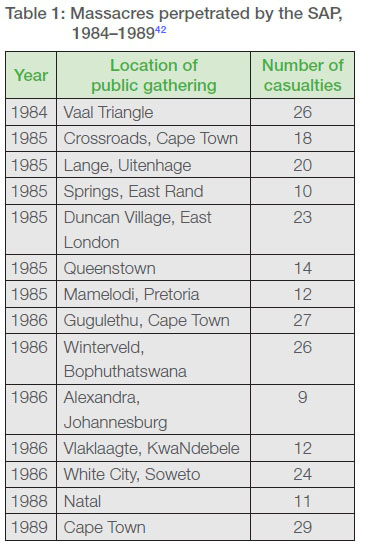

There was an intensification of mass lethal violence perpetrated by the police against black communities in the latter part of the 1980s. Table 1 provides details of some of these massacres. This type of police violence followed on from the declaration of partial states of emergency in 1985 and 1986.

Additionally, as stated in the 1985/86 SAP annual report, a 'large part of the South African Police was used on a full-time basis to combat unrest ... and [there was] intensified training of members, especially with regard to unrest and crowd control'.41

This police violence was linked to an unparalleled upsurge in the levels of protest violence against apartheid rule after the African National Congress (ANC) had called for mass mobilisation to 'make townships ungovernable'.43 This resulted in the destruction of government buildings and attacks on local government officials, suspected police informers and even policemen, and the ANC also called on its cadres to ambush police patrols and seize their firearms 'for future use'.44 This increase in township violence was acknowledged by the police in the 1984/85 SAP annual report, which referred to the violence as 'large-scale' and of 'serious proportions', and as having 'made heavy demands on the available manpower'.45

Although it is not possible to exclusively link specific reform processes to particular massacres perpetrated by the SAP in the mid to late 1980s, the apartheid government, in the context of numerous massacres (listed in Table 1), launched a new policing strategy, namely joint police/military crackdown operations in volatile townships with the stated objective of 'restoring normality'.46 The SAP also imported more sophisticated riot control equipment, including helicopters and armoured vehicles fitted with water cannons.47 In 1986 President PW Botha announced that the personnel strength of the SAP would be increased by 16% from just over 48 000 to 55 500.48 The Railways Police, which had been responsible for law enforcement and security in relation to the railway infrastructure and environment and had been historically separate from the SAP, was incorporated into the SAP. The SAP was also withdrawn from its national border protection responsibilities and replaced by soldiers. The size of the SAP was further increased during the latter part of the 1980s, with both the personnel size and budget of the SAP doubling between 1985 and 1990.49 This fortification of the SAP was also ultimately driven by concerns of the National Party government that its ability to contain and diminish protests by black political movements was under severe pressure.

The National Peace Accord and public order policing

By 1990, violence and criminality had escalated in numerous townships and some rural areas, and threatened to overflow into the relatively serene white residential and commercial enclaves, fundamentally destabilising the efforts of the apartheid government to maintain order. In response, the apartheid government and various political groupings signed the National Peace Accord (NPA) in 1991 in an attempt to bring an end to intense and pervasive political and criminal violence. As part of the NPA framework, the Goldstone Commission of Inquiry was established to investigate such violence.50 Evidence gathered by this commission implicated some SAP members in providing clandestine support for mass killings in ANC-aligned communities, perpetrated by Inkatha-affiliated hostel dwellers, for example in Sebokeng, Swanieville and Boipatong.51

As the fourth proposition (that police reforms will be pursued after massacres have taken place in the context of regime change) would suggest, the NPA included a major police reform imperative in response to the repressive and violent actions of the SAP. The NPA included a code of conduct, which specifically called for effective, non-partisan (or non-political), racially inclusive and more legitimate, community-focused and accountable policing.52The Goldstone Commission proposed the Regulation of Gatherings Bill (1993), which was only enacted after the 1994 elections, and stipulated that the police may only use force when public disorder cannot be forestalled through other non-violent methods.

The SAP's public order policing component was reorganised, but in a way that ran contrary to the spirit of the NPA. The Internal Stability Division (ISD) - a specialised militarised public order policing entity - was formed, with personnel who wore military-style camouflage uniforms, were armed with military-type weapons and were transported in military vehicles.53 Operational units were deployed to violence hotspots. In justifying the creation of the ISD, Hernus Kriel, the then minister of law and order, argued that: 'A man in a blue uniform must control political unrest as well as crime, and it doesn't work. That is why we believe there has to be a parting of ways.'54

These reforms were not only owing to operational considerations. The changes were also linked to political insecurities within the National Party government with regard to its ability to exercise effective control across South Africa, which was seen as waning considerably, and fears that its position would be weakened during the negotiations for a new constitution.55

Post-apartheid policing and the Marikana massacre

Since 1994 there have been various attempts to reform the public order component of the SAPS. In 1995, the SAPS public order policing unit was established, which merged personnel from the former riot units and internal stability units from the SAP and the various police forces from the self-governing Bantustan areas within South Africa, such as the Transkei and Ciskei. This merger was linked to the overall democratic policing reforms at the time, and aimed to engender a 'more soft approach than previous historical methods' to the policing of gatherings, marches and protests (including showing restraint and using force as a last resort).56 Public order policing personnel were 're-selected' and underwent training by Belgian police instructors, based on international standards of crowd management.57 This aimed to produce a slimmed down version of the apartheid riot control behemoth, but the public order policing unit remained a significant structure within the SAPS, totalling 7 610 members in 1997.58

The public order component was rebranded, reoriented and its members re-trained on two occasions. In 2001, following a reported decrease in incidents of public violence, these units were renamed area crime combating units (ACCUs). Informed by the principles of sector policing, the ACCUs were assigned an adjusted mandate to focus on serious and violent crimes. This was based on the SAPS assessment that incidents of violent public disorder had notably declined; moreover, there was a political imperative from cabinet for the SAPS to prioritise efforts to reduce violent interpersonal crime, particularly in high crime areas.59 Five years later the ACCUs were further rationalised into crime combating units (CCUs) with some 2 595 dedicated members. Specialised public order policing units were re-established in 2011 into 27 units with a total of 4 721 SAPS members, following an upsurge in violent protest actions.60

Despite these efforts, significant democratic reforms did not become effectively embedded within the ethos of the public order policing entities. Research undertaken in the early 2000s revealed that the leadership and members of the public order policing units were unwilling to relinquish 'established practices and symbolic representations of "discipline"', which undermined 'attempts at developing more participatory management techniques with consequences for broader transformational agendas'.61 Added to this, the ACCUs and the CCUs were heavily armed, sported military-style uniforms, made use of military organisational terms, such as 'company' and 'platoon', and retained a militarised outlook. In addition, such organisational changes resulted in an aggregate dilution of specialised public order policing knowledge and expertise.62 Training in this regard was also deprioritised.63

In August 2012, SAPS members opened fire on striking platinum mineworkers in Marikana (North West province), killing 34 and injuring 78 protestors. Due to mounting public pressure, an official commission of inquiry (the Farlam Commission) was established to investigate the massacre.64 In its submission to the commission the SAPS stated that those police that discharged their firearms against the striking mineworkers had done so in self-defence, as the mineworkers had behaved in a threatening manner, and appeared as though they intended to attack the police on the scene. The SAPS further stated that the mineworkers had ignored the police's instruction to lay down their weapons (which were mainly spears, sjamboks and sticks); that less lethal forms of crowd control, such as the use of water cannons, tear gas and rubber bullets, had failed to disperse the protestors; and that the police had been fired upon by at least one of the protestors.65

Evidence uncovered by journalists and researchers has suggested that a number of the deceased were executed by the police, some at point-blank range. Both published research and documentary films have strongly suggested that the police, acting in collusion with the affected mining companies and national government, adopted this strong-arm approach in an attempt to discourage widespread destabilisation of the mining sector labour force through additional strikes.66

The Farlam Commission found that in 17 of the deaths, the police 'had reasonable grounds to believe that their lives and those of their colleagues were under threat ... [which] justified them in defending themselves and their colleagues . but may have exceeded the bounds of self and private defence'.67 In relation to the other 17 deaths, the commission indicated that the deaths were likely the result of ineffective control by the SAPS that led to a 'chaotic free-for-all'.68 In sum, the commission attributed all of the deaths to overly-militarised policing methods used by the SAPS tactical units that had been ceded command-and-control during the massacre.

In line with the second proposition (that the police perceive that they are unprepared for the protest encounters), the SAPS indicated in its 2012/13 annual report that its public order policing units required additional resources, and that coordination structures had been established after the Marikana massacre to improve the SAPS response to, and investigation of, incidents of public disorder, with a focus on the prosecution of those responsible for such violence.69 Furthermore, in the 2013 State of the Nation address, Zuma instructed the Justice, Crime Prevention and Security Cluster (of which the SAPS is a component) to institute measures to ensure that violent protest actions 'are acted upon, investigated and prosecuted'.70

In addition, in 2014, while the Farlam Commission was still in existence, the SAPS sought support from the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Police for its plans to acquire in excess of R3 billion from the National Treasury to fund its 'turnaround' public order policing strategy. This entailed plans to substantially increase the number of public order policing units (from 27 to 50) and their personnel strength (from 4 721 to 8 759); and acquire large quantities of more forceful riot control equipment, such as armoured vehicles, stun/ anti-riot grenades, crowd dispersal acoustic devices and training facilities. Their motivation for the request was that violent incidents of public disorder had increased from 971 in 2010/11 to 1 882 in 2012/13, and that it was 'anticipated that this upsurge against state authority w[ould] not decline in the foreseeable future'.71

The Farlam Commission recommended in its 2015 report that public order policing in South Africa should be significantly reformed. In particular, it advocated that the use of automatic military assault firearms by police should be discontinued in the policing of protests; and that clear guidelines should be issued with regard to when the paramilitary components of the SAPS, such as the Tactical Response Team, are to be deployed in support of public order policing. It also recommended that a panel of experts should be established to determine amended rules and procedures for public order policing, based on international best practice. It also recommended that SAPS personnel should be effectively trained in relation to these rules and procedures.72 There have, however, been criticisms of the commission's findings, based on the view that it did not adequately and fairly engage with the accounts of the striking mineworkers.73

In 2016, based on the findings of the commission, the South African Treasury allocated additional budgetary resources to the SAPS for public order policing.74 In the same year, the Minister of Police appointed the panel of experts recommended by the Farlam Commission, and indicated that training in public order policing for police cadets had been increased from two to three weeks.75 A new national police instruction has also recently been finalised that replaces the previous public order policing standing order. This instruction declares that public order policing units are to be in control of the policing of public protests, and that authority should not be transferred to the more militarised tactical units of the SAPS. However, to date no funds have been provided to enhance independent oversight of the SAPS and to investigate abuses allegedly perpetrated by SAPS members.76

Conclusion

By means of a historical analysis of South Africa this article has explored five propositions in terms of the relationship between massacres perpetrated by the police, and subsequent police reform. It has demonstrated that in the context of public order policing, massacres by the police can contribute towards relatively immediate police reforms, particularly in terms of police strategies and tactics. In some circumstances, massacres even led to some restructuring of the police organisation.

The nature of the government and the environment of policing appeared to be key determinants of the types of police reforms post-massacre. That is, under apartheid, in instances where the police had felt that the protest action that culminated in the massacre was a serious threat to their ability to sustain social control, more militarised and oppressive reforms were pursued. This was the case with the Sharpeville and Soweto massacres. On the other hand, in the absence of a perceived threat to the police such police violence did not lead to noticeable police reforms, for example with the Bulhoek and Port Elizabeth massacres.

Furthermore, following a series of massacres and intense political violence, the successful negotiation of a peace agreement, the NPA, resulted in some restructuring of the SAP in the early 1990s. In addition, the events in the aftermath of the Marikana massacre, which took place under a democratic regime, show that mass lethal violence by the police has spurred initial attempts at reforming public order policing.

Notes

1 TA Critchley, A history of police in England and Wales, London: Constable, 1978; [ Links ] C Reith, The police idea: its history and evolution in England in the eighteenth century and after, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1938; [ Links ] D Arnold, The armed police and colonial rule in South India, 1914-1947, Modern Asian Studies, 11:1, 2008, 101-25. [ Links ]

2 MK Brown, Working the street: police discretion and the dilemmas of reform, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1988; [ Links ] J Chan, Changing police culture, British Journal of Criminology, 36:1, 1996, 109-34; [ Links ] DH Bayley, Police reform: who done it?, Policing and Society, 18:1, 2008, 7-17. [ Links ]

3 J Styles, The emergence of the police: explaining police reform in eighteenth and nineteenth century England, The British Journal of Criminology, 27:1, 1987, 15-22. [ Links ]

4 F Donner, Protectors of privilege: red squads and police repression in urban America, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990, 5. [ Links ]

5 E Marat, Kazakhstan had huge protests, but no violent crackdown: here's why, Washington Post, 6 June 2016, https://http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/06/06/kazakhstan-had-big-protests-without-a-violent-crackdown-heres-why/?utm_term=.02edf10a3d6b (accessed 29 August 2017).

6 PS Toggia, The state of emergency: police and carceral regimes in modern Ethiopia, Journal of Developing Societies, 24:2, 2008, 107-24. [ Links ]

7 W Teshome, Electoral violence in Africa: experience from Ethiopia, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 3:7, 2009, 1653-77. [ Links ]

8 M Dewar, Modernising interna security in Ethiopia, The Think Tank, 2008, http://almariam.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Modernizing-Internal-Security-in-Ethiopia.pdf (accessed 24 August 2017).

9 B Baker, Hybridity in policing: the case of Ethiopia, The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 45:3, 2013, 309. [ Links ]

10 CL Schneider, Police power and race riots in Paris, Politics & Society, 36:1, 2008, 133-59. [ Links ]

11 N MacMaster, Inside the FLN: the Paris massacre and the French intelligence service, University of East Anglia, March 2013, https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/55581/1/Zbookfinalcopy.pdf (accessed 29 August 2017).

12 R Francisco, After the massacre: mobilization in the wake of harsh repression, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 9:2, 2004, 107-26. [ Links ]

13 K Abdullah, National security and Malay unity: the issue of radical religious elements in Malaysia, Contemporary Southeast Asia, 21:2, 1999, 261-82. [ Links ]

14 R Peacock and G Cordner, 'Shock therapy' in Ukraine: a radical approach to post-Soviet police reform, Public Administration and Development, 36:2, 2016, 80-92. [ Links ]

15 PAJ Waddington, Police (canteen) sub-culture: an appreciation, British Journal of Criminology, 39:2, 1999, 287-309; [ Links ] Bayley, Police reform, 7-17.

16 P Imison, Mexico's efforts to tackle police corruption keep failing, Vice News, 21 March 2016, https://news.vice.com/article/mexicos-efforts-to-tackle-police-corruption-are-failing (accessed 30 August 2017).

17 P Alexander, Coal, control and class experience in South Africa's Rand revolt of 1922, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 19:1, 1999, 31-45. [ Links ]

18 J Rauch and D Storey, The policing of public gatherings and demonstrations in South Africa, 1960-1994, Braamfontein: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 1998. [ Links ]

19 I Evans, Cultures of violence: lynching and racial killing in South Africa and the American South, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010. [ Links ]

20 G Baines, South Africa's Amritsar? Responsibility for and the significance of the Port Elizabeth shootings of 23 October 1920, Contree, 34, 1993, 5. [ Links ]

21 D Webb and W Holleman, The sins of the fathers: cultural restitution and the Bulhoek massacre, South African Museums Association Bulletin, 23:1, 1997, 16-9. [ Links ]

22 DH Makobe, The price of fanaticism: the casualties of the Bulhoek massacre, Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, 26:1, 1996, 38-41. [ Links ]

23 C Nicholson, Nothing really gets better: reflections on the twenty-five years between Sharpeville and Uitenhage, Human Rights Quarterly, 8:3, 1986, 511-6; [ Links ] T Lodge, Sharpeville: an apartheid massacre and its consequences, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. [ Links ]

24 P Parker and J Mokhesi-Parker, In the shadow of Sharpeville: apartheid and criminal justice, Basingstoke: MacMillan, 1998. [ Links ]

25 South African Home Service, Parliament debates reasons for riots, 22 March, Johannesburg: South African Home Service, 1960. [ Links ]

26 PH Frankel, South Africa: the politics of police control, Comparative Politics, 12:4, 1980, 481-99. [ Links ]

27 Foreign Broadcast Information Service, Measures to strengthen police announced, Daily Reports, FBIS-FRB-61-045, 7 March 1961.

28 Ibid.

29 JD Brewer, Black and blue: policing in South Africa, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994; [ Links ] Frankel, South Africa, 481-99.

30 K Shear, Tested loyalties: police and politics in South Africa, 1939-63, The Journal of African History, 53:2, 2012, 173-93. [ Links ]

31 K O'Brien, Counter-intelligence for counter-revolutionary warfare: the South African Police Security Branch 1979-1990, Intelligence and National Security, 16:3, 2001, 27-59. [ Links ]

32 PM Cillié, Commission of inquiry into the riots at Soweto and elsewhere from the 16 June, 1976 - 28 February, 1977, Pretoria: Government Publisher, 1980. [ Links ]

33 M Marks and J Fleming, 'As unremarkable as the air they breathe'? Reforming police management in South Africa, Current Sociology, 52:5, 2004, 784-808. [ Links ]

34 A Mafeje, Soweto and its aftermath, Review of African Political Economy, 11, 1978, 17-30. [ Links ]

35 Johannesburg International Service, Soweto cordoned off, 17 June 1976.

36 Cillié, Commission of inquiry into the riots at Soweto and elsewhere from the 16 June, 1976 - 28 February, 1977.

37 Ibid., 117-118.

38 Ibid., 119.

39 Brewer, Black and blue.

40 G Cawthra, Policing in South Africa: the SAP and the transformation from apartheid, London: Zed Books, 1993, 102. [ Links ]

41 South African Police (SAP), Annual report of the Commissioner of the South African Police for the period 1 July 1985 to 30 June 1986, Pretoria: Government Printer, 1987, 1.

42 South African History Online, South African major mass killings timeline 1900-2012, 2012, http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/south-african-major-mass-killings-timeline-1900-2012 (accessed 4 July 2015).

43 African National Congress (ANC), ANC commentary on armed struggle, shift to offensive, Addis Ababa Radio Freedom, 18 October 1984.

44 Ibid.

45 SAP, Annual report of the Commissioner of the South African Police 1 July 1984 to 30 June 1985, Pretoria: Government Printer, 1985, 1.

46 Johannesburg Domestic Service, Drastic action defended, 24 October 1984.

47 South African Press Association (SAPA), Police import helicopters for riot control, 9 June 1985.

48 SAPA, Botha reviews, explains current issues, 23 April 1986.

49 O'Brien, Counter-intelligence for counter-revolutionary warfare.

50 This Commission of Inquiry, which was headed by Judge Richard Goldstone, was established to investigate political violence and intimidation between July 1991 and April 1994.

51 S Ellis, The historical significance of South Africa's third force, Journal of Southern African Studies, 24:2, 1998, 261-99; [ Links ] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (TRC), Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa final report, Cape Town: TRC, 1998; [ Links ] G Marinovich and J Silva, The bang-bang club: snapshots from a hidden war, New York: Basic Books, 2000. [ Links ]

52 Rauch, Deconstructing the South African Police.

53 Ibid.; Rauch and Storey, The policing of public gatherings and demonstrations in South Africa, 1960-1994.

54 SAPA, 'Specialised' unrest police force to be formed, 8 November 1991.

55 Cawthra, Policing in South Africa, 163-64.

56 South African Police Service (SAPS), Annual report of the South African Police Service 1 April 1996 - 31 March 1997, Pretoria: SAPS, 1997, 50.

57 S Tait and M Marks, You strike a gathering, you strike a rock: current debates in the policing of public order in South Africa, South African Crime Quarterly, 38, 2011, 15-22. [ Links ]

58 SAPS, Annua report of the South African Police Service 1 April 1996 - 31 March 1997.

59 B Omar, Crowd control: can our public order police still deliver?, South African Crime Quarterly, 15, 2006, 7-12. [ Links ]

60 Parliament of South Africa Research Unit, Analysis of public order policing units, Cape Town: Parliament of South Africa, 2014.

61 Marks and Fleming, 'As unremarkable as the air they breathe'?, 785.

62 B Omar, SAPS costly restructuring: a review of public order policing capacity, Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Monograph 138, 2007; B Dixon, A violent legacy: policing insurrection in South Africa from Sharpeville to Marikana, British Journal of Criminology, 55:6, 2015, 1131-48. [ Links ]

63 Parliament of South Africa Research Unit, Analysis of public order policing units.

64 It was officially referred to as the Marikana Commission of Inquiry and was headed by retired Judge Ian Farlam. The commission sat between October 2012 and November 2014. Its report was delivered to the state president at the end of March 2015.

65 SAPS, Heads of argument: SAPS, Marikana Commission of Inquiry, 2014, http://www.marikanacomm.org.za/docs/201411-HoA-SAPS.pdf (accessed 30 August 2017).

66 P Alexander et al., Marikana: a view from the mountain and a case to answer, Auckland Park: Jacana Media, 2012; [ Links ] R Desai, Miners shot down [documentary], Johannesburg: Uhuru Productions, 2014; [ Links ] B Dixon, Waiting for Farlam: Marikana, social inequality and the relative autonomy of the police, South African Crime Quarterly, 46, 2014, 5-12. [ Links ]

67 Marikana Commission of Inquiry, Report on matters of public, national and international concern arising out of the tragic incidents at the Lonmin mine in Marikana, in the North West Province, South African Human Rights Commission, 2015, 248, 545, https://http://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/marikana-report-1.pdf (accessed 30 August 2017).

68 Ibid., 312.

69 SAPS Annual Report 2012-13.

70 SAPS, Enhancing of the public order policing capacity within the SAPS briefing to Portfolio Committee on Police, 3 September 2014, http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/140903saps.pdf (accessed 1 December 2017).

71 Ibid.

72 Marikana Commission of Inquiry, Report on matters of public, national and international concern arising out of the tragic incidents at the Lonmin mine in Marikana, in the North West Province, 549.

73 P Alexander, Marikana Commission of Inquiry: from narratives towards history, Journal of Southern African Studies, 42, 2016, 815-39. [ Links ]

74 S Nyanda, R598m boost to overhaul public order policing, Daily Dispatch, 25 February 2016, http://www.dispatchlive.co.za/news/2016/02/25/r598m-boost-to-overhaul-public-order-policing/ (accessed 30 August 2017).

75 N Greve, Nhleko names public order policing panel, The Citizen, 2 May 2016, https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/1097976/nhleko-names-public-order-policing-panel/ (accessed 30 August 2017).

76 G Nicolson, Marikana: what's been done on SAPS recommendations?, Daily Maverick, 16 August 2017, https://http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-08-16-marikana-whats-been-done-on-saps-recommendations/-.WaaQhRSormE (accessed 30 August 2017).