Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Crime Quarterly

versión On-line ISSN 2413-3108

versión impresa ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. no.62 Pretoria dic. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2017/v0n62a3032

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Enabling the enabler. Using access to information to ensure the right to peaceful protest

Tsangadzaome Alexander MukumbaI; Imraan AbdullahII

IResearcher at the Legal Resources Centre. He holds an LLM (Tax) from the University of Cape Town. tsanga.mukumba@gmail.com

IIResearch officer at the Freedom of Information Project at the South African History Archive. He is an admitted attorney and holds an LLM (Human Rights Law) from the University of Johannesburg. The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and the Legal Resources Centre in no way binds or associates itself therewith. imraan@saha.co.za

ABSTRACT

The Regulation of Gatherings Act (RGA) places strict guidelines on how to exercise the right to protest, with particular emphasis on the submission of a notice of gathering to the responsible person within a municipality in terms of sections 2(4) and 3 of the Act. However, municipalities do not proactively make the notice of gathering templates available for public use (or may not have these at all), and often do not publicise the details of the designated responsible person. To test municipalities' compliance with the RGA, the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) enlisted the help of the South African History Archive (SAHA) to submit a series of Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) requests to every municipality in South Africa. PAIA requests were also submitted to the South African Police Service (SAPS) for records relating to public order policing. The initiative aimed to provide these templates and related documents to interested parties as an open source resource on the protestinfo.org.za website. The results of these efforts show that compliance with the RGA is uneven. This article explores the flaws in the regulatory environment that have led to this level of apathy within government, despite the crucial role of the right to protest and the right of access to information as enabling rights in our constitutional democracy. An analysis of the full PAIA request dataset shows the extent of government's resistance to facilitating these enabling rights, and provides insights into remedial interventions. The article concludes with a series of recommendations, which centre on statutory reforms to the RGA and PAIA to ensure appropriate sanction for non-compliance by government, proactive disclosure of relevant information, and emergency provisions allowing curtailed procedural requirements. The intention of the proposed amendments is to minimise the possibility that these fundamental, enabling rights might be frustrated.

'If your only tool is a hammer then every problem looks like a nail' - Abraham Maslow

The 'hammer' of the apartheid regime was secrecy and brute force, applied liberally to every uprising against the state. The use of this 'hammer' was enabled through laws such as the notorious Riotous Assemblies Act 17 of 1956,1 which has yet to be repealed.2 Despite the existence of suppressive laws, protest was used very effectively as a liberation tool during the apartheid era.3 Today, protest is not only a tool for addressing ongoing social struggles but also an empowering constitutional right that is used for a variety of causes, such as political engagement, demands for free education, and simply as a form of political expression.4 It has therefore been referred to as an enabling right.5It is not the only one; for example, the right of access to information is another enabling right.6An implication of recognising these enabling rights in the Constitution is that people in South Africa are empowered to pursue fundamental and socio-economic rights through participation in an active citizenry. In other words, those political rights are there to enable people to demand the realisation of other rights.

What happens, though, in a situation where the right to protest is heavily dependent on being sufficiently enabled by the state, as is required by section 7(2) of the Constitution?7 The Regulation of Gatherings Act 205 of 1993 (RGA) imposes strict procedural requirements on how to exercise the right to protest. Emphasis is placed on the submission of a notice of gathering in terms of section 3(2) of the RGA to the responsible officer in the jurisdiction of the municipality in which a gathering is planned.8Fulfilling this requirement is predicated on being able to access the information necessary to enable one to do so. Unfortunately, this information - the notice templates and the details of the responsible officers - is not proactively made available by municipalities, which results in protesters' having to struggle to obtain the necessary information.9 By not making the information accessible to the public, the state is arguably de facto limiting the right to protest.

Where a protest does go ahead, protesters should be subject to reasonable and proportionate policing responses, which take cognisance of the constitutional legitimacy of this form of political expression.10 Unfortunately this has not been the case, as protests that are viewed by the South African Police Service's (SAPS) public order policing (POP) unit as disruptive or involving violent elements, are often met with heavy-handed dispersal techniques.11Furthermore, municipal metropolitan police departments have become increasingly involved in crowd management and dispersal functions during protests, leading to questions about the lawfulness of the metropolitan police's involvement in policing protest, and the appropriateness of their training. There are no statutory or regulatory provisions that allow for the metropolitan police to be involved in public order policing beyond an initial, ancillary role. Despite this fact, the metropolitan police have become increasingly involved in actual public order policing.12

In addition, little is known about the make and model of crowd control weapons used by the SAPS POP, or about the training manuals that determine how the POP use crowd control weapons in assembly management situations.13 This information is important, because depending on the type and calibre of rounds used, severe injury can be caused. Consequently, protesters cannot anticipate the likely response when protests turn violent, and are unable to hold the police to their own operational standards.

Given that the state has not proactively provided the kinds of important information outlined above, it could be argued that our constitutional democracy has inherited the 'hammer' of secrecy and force. In light of this perceived culture of police abuse of power, the Legal Resources Centre sought to interrogate the extent of the state's fulfilment of its constitutional obligation to respect, protect and promote the rights contained in section 17 of the Constitution. To this end it approached the South African History Archive to assist with requests for information, to be submitted under the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000 (PAIA). PAIA requests were submitted in two phases, during the latter half of 2016 and the first quarter of 2017.14

In the first phase, PAIA requests were submitted to the SAPS and to eight metropolitan municipalities (metros). Requests that were submitted to the SAPS related primarily to the POP unit's equipment, training and standard operating procedures. Requests submitted to the metros focused on the increasing presence of the various metropolitan police departments in crowd management operations, as mentioned above, and sought to explore whether they were lawfully authorised to participate in crowd management operations beyond ancillary support, based on the provisions contained in the RGA and National Instruction 4 of 2014.15 Phase one requests therefore sought information about the existence of regulations that allowed metro police departments to engage in public order policing, and about the kind of equipment they used and the training they received.

In the second phase, PAIA requests were submitted to every municipality in South Africa where an information officer's contact details could be found. For a protest to be legally convened in South Africa, the RGA requires the convener of the gathering to give written notice to the relevant responsible officer.16Many municipalities require that this notice be provided via a template form, yet do not proactively make the templates available for public use. In practice, the convener of a protest must often jump through hoops to obtain a template, ascertain what information is required by the municipality in question, and find the details of the responsible officer. While the RGA does not require the completion of a specific form, expediency and good relationships with the responsible officer are improved by providing notice via the template, if one exists. The phase two PAIA requests therefore sought the contact details of the responsible officers and templates for notice in order to provide as many of these as possible as an open source resource on the protestinfo.org.za website for use by members of the public wanting to convene a gathering or protest.

The state's response to these requests was generally underwhelming and indicative of non-compliance with either or both the RGA and PAIA. There is a correlation between people's ability to access the information necessary to comply with the procedure for lawful protest, and their realisation of the right to protest itself. Without access to information enabling the right to peaceful protest, the promise of protest as a means to catalyse the realisation of social justice is frustrated.

Given these considerations, this article explores the flaws in the regulatory environment that have allowed this level of apathy to exist within government, despite the crucial role of the right to protest and the right of access to information as enabling rights in our constitutional democracy. An analysis of the full PAIA request dataset shows the extent of government's resistance to facilitating these enabling rights, and provides insights into remedial interventions. This article contains a series of recommendations, drawn from practical experience and centred on statutory reforms to the RGA (specifically) and PAIA (incidentally). These proposed reforms are geared to ensuring appropriate sanction for non-compliance by government and holders of the rights so as to provide measures to enable proactive disclosure of relevant information and emergency provisions. The proposed reforms would also create a more streamlined procedure, and minimise the possibility that these fundamental, enabling rights might be frustrated.

Protest and access to information as enabling rights

The right to peaceful protest and the right of access to information are important enabling rights in South Africa's constitutional democracy. Protest provides politically marginalised people with a means to express their dissatisfaction and apply pressure on governments to respond to their concerns. This is well demonstrated by South Africa's struggle against apartheid, where mass mobilisation was a crucial element in the matrix of forces that led to the realisation of democracy and the protection of fundamental rights through the Bill of Rights.

Peaceful assembly, demonstration, picketing, and the presentation of petitions are viewed by many in South Africa today as the most readily accessible means to ensure an accountable and responsive government during inter-election periods.17 This is due to the fact that section 17 of the Constitution guarantees ordinary people the right to protest, and enables them to communicate their dissatisfaction to the public and to apply collective pressure on government to provide more immediate access to fundamental rights.18

The enabling potential of the various rights contained in section 17 is explicitly recognised by the Constitutional Court in South African Transport and Allied Workers' Union and Another v Garvas and Others.19The court was called upon to determine the constitutionality of section 11(2) of the RGA, which imposes liability on the conveners of a gathering where reasonably foreseeable damage to or destruction of property is not adequately prevented. The majority per Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng held that 'in assessing the nature and importance of the right [to protest], we cannot ... ignore its foundational relevance to the exercise and achievement of all other rights'.20 These sentiments were echoed by the minority per Justice Chris Jafta, who held that '[it] is through the exercise of each of these rights that civil society and other similar groups in our country are able to influence the political process, labour or business decisions and even matters of governance and service delivery'.21

Positioning the right to protest at the core of our democracy and the realisation of other rights in the Bill of Rights creates a strong presumption against unwarranted derogation, and provides a strong impetus on the state to actively facilitate peaceful protest.22 Government's regulation of protest and levels of assistance to potential protesters or conveners must therefore be judged in this light.

The RGA sets out the requirements for lawful protest. These requirements include the submission of a notice of gathering in terms of section 3 of the Act to the responsible officer, who is designated under section 2(4) (a). Even though section 3 does not require that the notice be placed on a specific form, in practice municipalities frequently require that these notices be lodged on their own template. Municipalities are therefore arguably acting unlawfully and unconstitutionally, as this requirement is neither justified in terms of a law of general application nor defended under section 36 of the Constitution. In the absence of access to information about how and where to give notice, and details of who the responsible officer is, potential protesters And it difficult to comply with these requirements. Tsoaeli and Others v S (Bophelo House) held that the conveners of gatherings bear the responsibility of notifying the local authority.23 The fact that this information is not made proactively and easily accessible, hampers conveners' ability to exercise their constitutional rights within the parameters of the current legal framework.

The Constitutional Court, in Brümmer v Minister for Social Development and Others, held that 'access to information is fundamental to the realisation of the rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights'.24 Without access to the information that can enable lawful protest, further constitutional rights, including the right to bodily integrity and the right to life, are in turn imperilled. The provision of notice by the conveners of a protest serves several purposes, but mainly facilitates a response by organs of state. The post-notice meetings, which may be called under section 4(2)(b) of the RGA, help ensure that the state responds to the protest action in an appropriate manner. This ranges from ensuring adequate traffic control to a sufficient police presence. Where protesters are unable to provide notice, there is a greater likelihood that they will face a state response that is ill-considered or fails to implement measures such as traffic control, meant to ensure that the disruption does not cause undue harm.25

The right of access to information held by the state, as enshrined in section 32(1)(a) of the Constitution, must therefore be treated as equally crucial to the full realisation of rights in the Bill of Rights, as is the right to protest. Unfortunately, evidence gathered through the PAIA requests indicates a complete disregard by the state of the role of easily accessible information in enabling and regulating peaceful protest.

The PAIA requests26

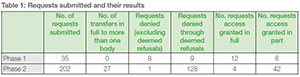

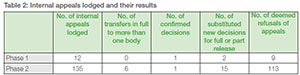

The PAIA requests were submitted in two phases, and the results of these requests are presented below in tables 1 and 2. Table 1 shows the number of initial requests that were submitted (35 in the initial phase, and 202 in the follow-up phase). The remaining columns set out the outcomes of these requests. Table 2 follows the same format, but depicts the results of internal appeals that were lodged in response to the outcomes from Table 1. Overall, the data presented in the tables show poor compliance with the statutory requirements of PAIA, which not only has a negative direct impact on the right to protest but also has an ancillary impact on the right of access to information. The nuances of these results are discussed in further detail below.

Understanding the PAIA request statistics

A striking feature of the outcome of the PAIA requests submitted as part of this project was the number of deemed refusals, both at the initial stage and at the appeal stage. A deemed refusal occurs when a requestee body does not respond to a PAIA request within the statutory time frame of 30 days.27 Deemed refusals were recorded in both phase one and phase two of the request processes, and these findings are consistent with general trends in PAIA request statistics, as highlighted yearly by the Access to Information Network in its shadow reports.28The Access to Information Network's Shadow Report for 2017 indicates that this trend continues, particularly among municipalities, with only 171 of 216 requests being responded to within the timeframe set out in the statute.29This suggests that the right of access to information is not being effectively facilitated by municipalities, likely owing to inadequate levels of training or capacity in the lower spheres of government responsible for enabling the right of access to information.30

Where responses were received, they were often inadequate. In some cases, these responses were so inadequate that they resulted in internal appeals being lodged. An internal appeal is a process set out in PAIA, in terms of which a requester can submit an appeal against the decision or deemed decision of the information officer of certain state requestee bodies.31 The political head of that body (for example, the mayor or the Speaker in the case of a municipality) then reviews the decision of the information officer, who is the administrative head of the body, and, in the case of a municipality, its municipal manager. The relevant authority can either confirm or reverse the decision of the information officer. In cases where the decision is reversed, the relevant authority must indicate whether the new decision either grants or denies access, with reasons for denial based on provisions in PAIA.32

Responses received under phase one of the project were often contradictory. In some instances, one municipality would deny access to the records by relying on the mandatory protection of safety of individuals and the protection of property,33 whereas another municipality would release the same records. For example, our phase one requests to the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality and the City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality (COT) were refused, relying on the justification that their release would endanger the public. On the other hand, the City of Cape Town (COCT), and the City of Johannesburg (COJ) metropolitan municipalities as well as the SAPS, all released the records without any reservation. When this inconsistency was pointed out to the COT on internal appeal it revised its original decision, and released the requested records.

The requests for training manuals revealed that some metro police were receiving formal training in public order policing from the SAPS. None of the released records showed authorisation for this training in terms of any statutory or regulatory provisions. This implies that the metro police are receiving training from the SAPS to act beyond their legislated purview, as metro police are only mandated by National Instruction 4 to be first responders to a spontaneous protest. While we recognise that the POP's resources may be limited, which circumscribes its ability to respond to all spontaneous protests, there ought to be a legislative or regulatory provision guiding interventions by metro police at gatherings. Without this mandate, there is no way to guide expectations as to the extent of involvement of metro police officers in policing gatherings. This is critical, as National Instruction 4 does not sanction metro police to use force at gatherings and assemblies, yet they possess and carry crowd control weapons.34

Even though PAIA does not expressly require record creation, only decisions on access to existing records, phase one saw several useful documents being created by requestee bodies in response to our requests. For example, the SAPS created a spreadsheet containing all the authorised members' contact details throughout the country.35 This is an incredibly useful tool for potential protest conveners and the provision of this information is in keeping with the spirit of PAIA, which requires an open and transparent approach to the management of state affairs. Another example was the COJ's creation of records that detail the make and model of the weapons used by the Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department, which allows experts to analyse the type of weapons being used to police protests, and potentially challenge their use should they lead to disproportionate harm.36The fact that these requestee bodies went the extra mile in facilitating access to information is commendable and should be an example of how to be proactive and facilitate a culture of transparency.

Phase two was extremely laborious and entailed SAHA's Freedom of Information Programme (FOIP) team manually sourcing the contact details of information officers for almost all of the municipalities in the country. This was owing to the fact that only a handful of municipalities have complied with the statutory requirement to create a PAIA Manual, which contains (among other things) the contact details of the information officer for the public body, and to make this manual accessible from a website.37This laborious activity did, however, have a positive spin-off: once details were obtained for a municipality, a profile was created on SAHA's requestee database, which is publicly accessible on FOIP's website. This makes the submission of future PAIA requests much easier for the public.38 However, despite the project's efforts to collect up-to-date contact details and submitting PAIA requests to these officials, in the end close to 80% of those municipalities simply ignored the requests. If a request is not responded to within 30 days PAIA automatically deems it to have been refused by the requestee body. Where requests are deemed refused, or are simply ignored, requesters can challenge the failure to respond, either through court process or, where applicable, through internal appeal.

The FOIP submitted internal appeals against these deemed refusals. A small minority of municipalities quickly reverted and released the records, but the majority failed to respond in any way to these appeals. This is particularly concerning, as the requests were not only an exercise of the right of access to information but were also specifically related to the exercise of the right to protest - both of which are constitutionally enshrined fundamental human rights.39 In some instances, even where records were released, these were non-compliant in terms of the Act. For example, instead of a blank template, some municipalities released completed notices of gatherings, riddled with personal information which they had an obligation to redact in terms of sections 34 and 28 of PAIA. Not only are these records unusable as templates but their release also demonstrates a complete disregard of the mandatory duty to protect the information of third parties.40 Municipalities that were made aware of these errors rectified their mistakes by subsequently releasing blank copies of the notice of gathering templates to FOIP instead.

Another notable issue that came to the fore because of the request process was that an anomaly was observed in terms of the applicability of the RGA. District municipalities, as oversight offices, have no responsibilities in terms of the RGA. This came to light when the FOIP team submitted PAIA requests to every district municipality, and the information officers of several of those district municipalities responded that they did not have the records we had requested, as the RGA did not apply to them.41 This raises questions around the scope of the oversight role of district municipalities.

These municipalities arguably have oversight of all key issues and functions, and such oversight requires access to records related to those key issues and functions. It is therefore puzzling that district municipalities do not have copies of important documents related to key issues and functions of local municipalities within their districts in their own archives. Fortunately, PAIA makes provision for these kinds of circumstances. The Act provides that the information officer who determines that a particular record is not in the possession of the public body to which the request was made, but with another public body, must transfer the PAIA request to such other public body.42Information officers of the district municipalities were largely responsive to the PAIA requests. However, this remains a deficiency in the RGA, and ought to be addressed by giving district municipalities clear overarching responsibility to ensure that the local municipalities within their jurisdiction are RGA compliant. This could be done both in terms of having notice templates available and through their involvement in the actual RGA notice procedure - potentially in the form of a review of the involvement of local municipalities' responsible officers in section 4 RGA consultative meetings, or by including those municipalities in the meetings.

Recommendations

While the PAIA request project has yielded some victories in terms of the right to protest and the right of access to information, the project's activities have exposed serious deficiencies in the relevant laws and the state's implementation of these laws. The primary finding was that organs of state have indeed inherited the ethos of secrecy from the apartheid regime, and portray a similar resistance to the expression of participatory democracy through protest. There ought, therefore, to be a push to close any legislative gaps that allow the state to avoid its obligations to respect, protect and promote the rights in sections 17 and 32 of the Constitution.

We propose the following recommendations to enable the realisation of these rights.

Regulation of Gatherings Act

The primary object of the RGA is to facilitate the section 17 rights in the Constitution; and with the positive obligation on the state to take steps to promote and fulfil rights in the Bill of Rights as per section 7(2) of the Constitution, there is a clear duty on the state to proactively facilitate protest. However, the only provision within the RGA that requires the state to act proactively is section 3(1), which requires responsible officers to assist conveners to reduce their notices to writing if the conveners are unable to do so. Considering the legislative scheme of the RGA, which includes notice requirements and potential civil and criminal liability, this does little to meet the constitutional obligations described above. What is missing from the RGA is a clear, positive duty on organs of state to be available to assist with the notification procedure and to respect the legitimate expression of democratic participation during the protest itself.

The spectre of both civil and criminal prosecution looms over conveners of protests where the protest involves the destruction of property, as in Tsoaeli, or where failing to satisfy the notice requirements may result in a criminal conviction. While the potential for civil liability may be a justifiable limitation on the rights in section 17, where a protest results in destruction of property, it is unlikely that being held criminally liable for the mere failure to give notice of a peaceful protest will be regarded by a court of law as a constitutionally justifiable limitation of those rights. This is currently under review in a case involving the Social Justice Coalition (SJC). In 2015, following a protest outside the Cape Town Civic Centre, 10 protest conveners representing this organisation were convicted for contravening section 12(1)(a) of the RGA for having convened a protest, which was peaceful and unarmed, without complying with the notice requirements contained in section 3.43 This conviction is currently on appeal and it has been argued by the appellants that section 12(1)(a) is unconstitutional.44 The crux of the argument lies in the fact that the state needs to be able to demonstrate that a limitation of a right (such as the need to give notice prior to the exercise of the right to protest) is reasonable and justifiable.

Given that there are means available to the state to achieve the purpose of the notice provisions - namely that there is an appropriate state response that will ensure the safety of protesters, the general public and the officials involved - that are less restrictive, it is unlikely that these provisions will stand up to constitutional scrutiny. The depth of the limitation of the right is clear; the possibility of being jailed for exercising a constitutional right is both a deterrent to and grievous consequence of legitimate democratic expression, particularly where the protest is peaceful.45

This SJC case highlights a fundamental concern that the PAIA requests brought to light with respect to the RGA, namely that the notice procedure has become an unjustifiable obstacle to legitimate democratic expression of discontent. This must be remedied. How to do so is perhaps less clear, as the notice requirement does serve a legitimate administrative coordination purpose, and it ought not to be done away with completely. At a minimum, therefore, the information required to comply with notice requirements, such as contact details for responsible officers, should proactively be made available to the public. The RGA should therefore be amended to require that this information be recorded and displayed at municipal offices and on municipal websites. It is further submitted that, along with the removal of criminal sanction for non-compliance with notice requirements by protesters, provision should be made for some form of sanction to be applied to officials responsible for facilitating protest, in the event that they fail to take reasonable steps do so or are obstructive to the process (negligently or intentionally). This will ensure that the positive duty to respect, protect and promote the enjoyment of section 17 is duly fulfilled by the functionaries of the state.

Promotion of Access to Information Act

The intersection between the right to protest and the right of access to information has brought to light the need for emergency access to information provisions to be included in PAIA. This is because, as noted above, protests, to be effective, often take place at short notice. The timeframes within PAIA for the processing of requests for information would effectively stifle the exercise of the right to protest, if information required to protest lawfully needs to be accessed using PAIA. There are numerous circumstances that may give rise to the need to access information at short notice to avoid limiting the exercise of a constitutional right. Access to medical records to ensure appropriate emergency medical care is one such example. Parliament should therefore consider making provision within PAIA for processing requests at shorter notice, where such emergency requirements can be demonstrated.

The poor compliance with PAIA by local authorities has highlighted the need for the Information Regulator's Office to be sufficiently resourced to provide comprehensive training at a local government level. Training needs to be focused not only on compliant processing of PAIA requests but also on the importance of PAIA as legislation giving effect to a right that enables the exercise of other rights, be they constitutionally enshrined or not.

In relation to the PAIA requests referred to in this article, adequate reasons for refusal of access were never provided to SAHA, as is required by section 25 of PAIA. Such adequate reasons ought to, in line with section 25 of PAIA, include a demonstration as to why grounds for refusal provided for in PAIA are applicable to the relevant record/s to which access is denied. Given the large number of refusals (including deemed refusals) of both SAHA's requests and appeals, the only further avenue open to SAHA -approaching the courts to obtain relief - was too resource intensive to be viable. Another available option is to approach the Information Regulator, who has the authority to decide on this kind of dispute. Currently, however, this office functions with only five commissioners and no support staff. We therefore recommend that Parliament allocate sufficient budget to make this office fully functional.

Notes

1 It is important to note that there were other oppressive laws enacted, such as the Suppression of Communism Act, which became part of the Internal Security Act 1982. The Public Safety Act 1953 (Act 3 of 1953) also contained provisions that allowed the government to declare states of emergency in various parts of the country.

2 See Kevin Brandt, Motlanthe: Riotous Assemblies Act is outdated, should be reviewed, EWN, http://ewn.co.za/2016/12/06/motlanthe-riotous-assemblies-act-is-outdated-should-be-reviewed (accessed 24 November 2017), where the High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and Acceleration of Fundamental Change, chaired by former president Kgalema Motlanthe, stated that the law does not belong in a constitutional democracy.

3 Stu Woolman, Freedom of assembly, in Stu Woolman and Michael Bishop (eds), Constitutional law of South Africa, Cape Town: Juta, 2008, ch 43, 4-6. [ Links ]

4 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 (Act 108 of 1996), section 17, guarantees the right to assemble, demonstrate, picket, and present petitions. See also Woolman, Freedom of assembly, ch 43, 7-9.

5 South African Transport and Allied Workers Union and Another v Garvas and Others (CCT 112/11) [2012] ZACC 13, para 63. See also Lisa Chamberlain, Assessing enabling rights: Striking similarities in troubling implementation of the rights to protest and access to information in South Africa, African Human Rights Law Journal, 16, 2016, 365, 368.

6 1996 Constitution, section 32 guarantees the right of access to information. See also Brümmer v Minister for Social Development & Others (CCT 25/09) [2009] ZACC 21, para 63; Fola Adeleke and Rachel Ward, The interrelation betweenhuman rights norms and the right of access to information, ESR Review: Economic and Social Rights in South Africa, 6:3, January 2015, 7. [ Links ]

7 The duty to enable is drawn from the positive obligation on the state to respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights in the Bill of Rights under section 7(2) of the Constitution.

8 A gathering is defined in section 1 (iv) of the Regulation of Gatherings Act 1993 essentially as an assembly of more than 15 people in a public space for a political or popular mobilisation purpose.

9 It is beyond the scope of this article to delve into the fact that municipalities can refuse to allow the protest to take place and actively do so in conjunction with metro police departments. Jane Duncan, Protest nation: the right to protest in South Africa, Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2016, 11-12, 15-18.

10 The right to peaceful assembly, demonstration, picketing and presentation of petitions is enshrined in section 17 of the Constitution.

11 Sean Tait and Monique Marks, You strike a gathering, you strike a rock, SACQ, 38, 2011, 15, 17-19. [ Links ]

12 Section 14 of the National Instruction 4 of 2014 clearly states that the metro police should engage in crowd management operations as first responders until the trained POP members arrive. The metro police are not allowed to use force or disperse the crowd; they are only mandated to contain the situation. It is thus surprising to see that they are armed with equipment that is intended to exert force.

13 See Physicians for Human Rights and International Network of Civil Liberties Organizations (INCLO), Lethal in disguise: the health consequences of crowd control weapons, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), https://www.aclu.org/report/lethal-disguise-health-consequences-crowd-control-weapons (accessed 15 August 2017).

14 These requests can be viewed, filtered and analysed at South African History Archive (SAHA), PAIA Tracker, http://foip.saha.org.za/request_tracker/search (accessed 24 November 2017).

15 National Instruction 4 of 2014, section 14.

16 Regulation of Gatherings Act 1993 (Act 205 of 1993), section 3.

17 Ian Currie and Johan de Waal, The Bill of Rights handbook, 6 edition, Cape Town: Juta, 2013, 379; [ Links ] Stu Woolman, My tea party, your mob, our social contract: freedom of assembly and the constitutional right to rebellion in Garvis v SATAWU (Minister for Safety & Security, third party) 2010 (6) SA 280. (WCC), South African Journal on Human Rights, 27, 2011, 346, 347-349. [ Links ]

18 Ibid.

19 South African Transport and Allied Workers' Union and Another v Garvas and Others [2012] 10 BLLR 959 (CC).

20 Ibid., para 61.

21 Ibid., para 120.

22 1996 Constitution, section 7(2).

23 Tsoaeli and Others v S (Bophello House) (A222/2015) [2016] ZAFSHC 217.

24 Brümmer v Minister for Social Development and Others 2009 (11) BCLR 1075 (CC), para 63.

25 Tait and Marks, You strike a gathering, 17.

26 A more detailed version of the statistics can be accessed upon request to SAHA's Freedom of Information Programme. The tables herein represent a summarised version of the statistics.

27 Promotion of Access to Information Act 2002 (Act 2 of 2002), section 27.

28 See Shadow Reports for 2009-2016 at SAHA, PAIA reports and submissions, http://foip.saha.org.za/static/paia-reports-and-submissions (accessed 8 November 2017).

29 Imraan Abdullah, Shadow Report 2017: access to information, SAHA, 2017, 4, http://foip.saha.org.za/uploads/images/Shadow%20report%20Booklet%20corrected%20final.pdf (accessed 28 October 2017).

30 Approximately 600 public officials from various departments participated in the training workshops conducted by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) during the reporting period, with only one municipality approaching the SAHRC for training on PAIA. This is concerning because local government consistently remains the least compliant with PAIA of all spheres of government, despite being the sphere with the most direct contact with members of the public. During the reporting period almost 80% of municipalities failed to comply with PAIA. SAHRC, SAHRC PAIA report 2014/2015, 14, https://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/Final%20annual-report%20.pdf (accessed 28 October 2017).

31 '"information officer" of, or in relation to, a public body ..

(b) in the case of a municipality, means the municipal manager appointed in terms of section 82 of the Local Government: Municipal Structures Act, 1998 (Act 117 of 1998), or the person who is acting as such'.

32 Promotion of Access to Information Act, section 77(2).

33 Ibid., section 38(a) and (b).

34 National Instruction 4 of 2014, section 14.

35 See SAHA, Designated 'authorized members', http://foip.saha.org.za/request_tracker/entry/sah-2016-sap-0012 (accessed 24 November 2017) for further information as well as access to the record.

36 See SAHA, Crowd management equipment, weapons and ammunition, http://foip.saha.org.za/request_tracker/entry/sah-2016-jhb-0002 (accessed 24 November 2017) for further information as well as access to the record.

37 Promotion of Access to Information Act, section 14; Municipal Systems Act 2000 (Act 32 of 2000), section 21.

38 See SAHA, Requestees search, http://foip.saha.org.za/requestee/search (accessed 24 November 2017).

39 1996 Constitution, section 32 and 17.

40 Promotion of Access to Information Act, section 34.

41 The Regulation of Gatherings Act defines 'local authority' as: 'Any local authority as defined in section I of the Promotion of Local Government Affairs Act. 1983 (Act No. 91 of 1983), within whose area of jurisdiction a gathering takes place or is to take place, but does not include a regional services council or a joint services board in respect of the area of jurisdiction of another local authority.' The Act specifically excludes the regional services council - in which capacity district municipalities currently serve.

42 Promotion of Access to Information Act, section 20(a).

43 Cape Town Magistrates' Court Case No. 14/985/2013.

44 The Appellants' Heads of Argument are available at Social Justice Coalition, The 'SJC10': civil disobedience and challenging apartheid laws, http://www.sjc.org.za/sjc10 (accessed 24 November 2017).

45 See para 73-132 of the Heads of Argument filed on behalf of appellants in Case No: A431/15 Western Cape High Court.