Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.61 Pretoria Sep. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2017/v0n61a2046

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A losing battle? Assessing the detection rate of commercial crime

Trevor BudhramI; Nicolaas GeldenhuysII

ISenior lecturer in Forensic Investigation at the University of South Africa and holds a PhD in Police Science. budhrt@unisa.ac.za

IIForensic investigator and holds a Masters degree in forensic investigation. geldenhuysndc@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The South African Police Service (SAPS) struggles to protect victims from commercial crime that threatens the economy, corrodes scarce and valuable resources, and inhibits growth and development. Official SAPS statistics show that the annual detection rate in respect of reported fraud cases was 35.77% in 2014/15 and 34.08% in 2015/16. Although the detection rates for serious commercial crime are reported as 94.8% for 2014/15 and 96.75% for 2015/16, it is likely that these figures are inaccurate and, in reality, much lower. This article provides an overview of the reported incidence of commercial crime, assesses the detection rate reported by the SAPS, and seeks to determine how it can be improved.

Commercial crime has a profound impact on the economy, trade and society at large. Individuals, businesses, organisations and government suffer the consequences of these crimes, which are committed for financial gain and include fraud, theft, forgery, corruption, tax evasion, embezzlement, money laundering and racketeering, as well as facilitating, receiving and possessing the proceeds of crime. However, the relative lack of attention to and authoritative criminal sanction of commercial crimes in South Africa are of great concern. For example, various cartels that have colluded in price-fixing and related corruption in the food, steel and construction industries in recent years, have merely received administrative penalties.1Furthermore, as will be seen from this article, commercial crime is under-reported, and the limitations of official statistics remain a challenge. This article reviews the data on commercial crime in South Africa, assesses its detection by police, and considers how it can be better tackled.

Commercial crime

The concept of commercial crime is closely related to white-collar crime, financial crime and economic crime. The term white-collar crime was coined by sociologist Edwin H Sutherland in 1939 and is defined as 'crimes committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation'2 In 1970 Edelhertz extended the definition of white-collar criminality to include any 'illegal act or series of illegal acts committed by nonphysical means and by concealment or guile, to obtain money or property, to avoid the payment or loss of money or property, or to obtain business or personal advantage'.3

The understanding and scope of white-collar crime have evolved and it now includes an array of different crimes that did not form part of the original concept. Terms such as financial crime, economic crime, commercial crime and corporate crime are used interchangeably with white-collar crime.4 The most prevalent characteristics of these crimes include the absence of violence, a motive of financial gain, an actual or potential loss, and an element of misrepresentation, concealment, deceit or a violation of trust.5 The SAPS uses the term commercial crime, which includes the criminal acts of fraud, embezzlement, theft of trust funds, corruption, forgery, uttering, money laundering and certain computer-related and cybercrimes, as well as statutory offences relating to finance, trade, commerce, business, corporate governance, tax, corruption, money laundering and the proceeds of crime and intellectual property, but excludes the physical misappropriation (theft) of moveable property.6The SAPS also distinguishes between general, less serious commercial crime and serious commercial crime.7

Investigation of commercial crime

Commercial crime is investigated primarily by the SAPS, as well as by non-SAPS government investigators and, in a private capacity, bank, corporate and private investigators. The legal framework for the investigation of crime is established by Section 205(3) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 (Act 108 of 1996), which places a legal obligation on the SAPS to prevent, combat and investigate crime. This is supported by the South African Police Service Act 1995 (Act 68 of 1995), the Criminal Procedure Act 1977 (Act 51 of 1977, the CPA) and various other statutes.

The investigative capacity of the SAPS comprises four sub-programmes that fall under Departmental Programme 3: Detective Service, of which two (General Crime Investigations and Specialised Investigations) perform the actual investigation work while the others (Criminal Record Centre and Forensic Science Laboratory) provide investigation-related support and forensic services.8 The mandate for the investigation of non-serious commercial crime rests with the General Crime Investigation component of the Detective Service (i.e. station-level detectives), while serious and priority commercial crime is investigated by the Serious Commercial Crime component of the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI).9 In 2016 a new national head, Commercial Crime was appointed outside of the DPCI and a Commercial Crime Unit under the control of the divisional commissioner, Detective Service was re-established, going back to the situation prior to the inclusion of the former Commercial Branch in the DPCI in 2009.10 It is envisaged that the Commercial Crime Unit will investigate commercial crime cases not investigated by the DPCI, but which are too complex for investigation at station level. At least 14 non-SAPS government-related institutions and agencies have a statutory mandate to investigate, inter alia, commercial crimes.11

Incidence of reported commercial crime

The SAPS annually releases limited statistics relating to reported commercial crime. A distinction is made between general, less serious commercial crime and serious commercial crime. The SAPS has a tendency to equate general, less serious commercial crime with fraud.12 However, neither the number of new cases or complaints for all commercial crime collectively, nor the financial cost (losses) in respect of general, less serious commercial crime is published. Table 1 reflects reported commercial crimes for the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2016.13

An issue for concern is that different sets of data have been published by the SAPS in respect of general, less serious commercial crime for the above period. The SAPS annual crime statistics show that 76 744, 67 830 and 69 917 commercial crimes were reported during 2013/14, 2014/15 and 2015/16 respectively.18The differences between the two sets of figures are quite significant and arguably warrant further investigation as to their accuracy and origin.

If one compares the available SAPS commercial crime figures (i.e. fraud) for 2013/14 (79 109 new cases) with that of fraud reported as serious commercial crime (4 271 new cases), the latter constituted 5.4% of the overall fraud cases received for investigation by the SAPS. Furthermore, a total of 13 839 persons were arrested for fraud during 2013/14; of those 2 403 (17%) for serious fraud.19

The above figures illustrate that significant losses can be attributed to those commercial crimes reported to the police. Almost R118 billion was lost between 2013 and 2015 as a result of reported serious commercial crime. During the two-year period 2012-2013 a total of 170 678 new fraud cases were reported to the SAPS. During 2015/16, an average of 200 commercial crimes were reported to the SAPS each day. Serious fraud made up more than 5% of all reported fraud and about 66% of all serious commercial crime cases. In terms of geographical distribution, Gauteng has the highest incidence of fraud reported to the SAPS, at 33.9% in 2015/16.20

According to the Global Economic Crime Survey 2016, published by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), which covers the period 2014 to 2015, 69% of participants in South Africa had experienced economic crime during the reporting period.21 The most prevalent economic crimes were asset misappropriation, procurement fraud, bribery, corruption, cybercrime, human resources fraud, accounting fraud and money laundering. Apart from cybercrime the incidence of the other six types was higher than the global average. Cybercrime was on par with the global average. A total of 60% of participants lost in excess of R500 000 during the reporting period as a result of economic crime.22

Taking into account the above figures, the enormity of commercial crime and its penetration into society, government and the business sector cannot be disputed. The under-reporting of commercial crime exacerbates the situation, so that one can only imagine the real extent and consequences of commercial crime on the economy and society at large.

Under-reporting

It is notoriously difficult to gauge the incidence and quantify the monetary impact of commercial crime on society and the South African economy. PwC found that gross under-reporting by victims of economic crime is the norm in South Africa.23 For the period 2014 to 2015, 66% of respondents surveyed indicated that they address incidents of economic crime internally, using in-house resources, rather than reporting it to the authorities.

The Victims of Crime surveys 2014/15 and 2015/16 show that, respectively, 26.8% and 35.0% of consumer fraud incidents were reported to the SAPS.24 This suggests that about two-thirds of consumer fraud are not reported to the SAPS. The two main reasons for the low reporting rate are that victims have reported the crime to other authorities, and the perception or belief that the police could not or would not do anything about it. Bruce argues that crime is widely under-reported in South Africa and that official crime statistics issued by the SAPS do not accurately reflect the real crime situation.25 Crimes that require a police reference number for insurance purposes (e.g. housebreaking, robbery, vehicle theft and theft out of vehicle) are more likely to be reported. The above findings confirm that the incidence of commercial crime is in reality much higher than what is officially reported.

SAPS performance in respect of commercial crime investigation

According to the SAPS Annual Performance Plan 2016/17 and the Performance Information Management Framework 2016/17, the purpose of the Detective Service is to perform (enable) the investigative work of the SAPS, including support to investigators in terms of forensic evidence and the Criminal Record Centre.26The strategic objective of the Detective Service is to contribute to the successful prosecution of offenders (crime), by investigating, gathering and analysing evidence, thereby increasing the detection rate of priority crime. The performance of the SAPS in respect of the investigation of crime is measured using three performance indicators, namely the detection rate, the trial-ready docket rate and the conviction rate.27

Detection rate

The detection rate is an indication of successful investigations achieved in respect of the SAPS's active investigative workload, which consists of new crimes reported to the SAPS as well as older cases that have not been finalised but are carried over from previous financial years.28 The detection rate measures the ability of the SAPS to solve crimes during investigation. The SAPS views a successful investigation as one that has resulted in the positive identification, arrest and charging of a perpetrator, cases that are withdrawn by the complainant before a perpetrator is charged, and cases where the public prosecutor declines to prosecute ('nolle prosequi' decisions), as well as unfounded cases.29

The rationale for the inclusion of unfounded cases and cases withdrawn out of court in the detection rate is not clear. Since these cases often involve little or no investigation at all, it does not make sense to regard all of them as successful investigations. Yes, in certain cases where a suspect was identified and a considerable amount of time and resources spent on an investigation, only to be withdrawn by the complainant before any charge was brought, it might be argued that it was a successful investigation. However, there is no indication that factors such as time and resources spent are considered when deciding whether to include an unfounded case or a case withdrawn out of court in the detection rate. We argue that the blanket inclusion in the detection rate of all unfounded cases and cases withdrawn out of court before a suspect is charged, results in a skewed picture of the actual ability of the SAPS to solve crime.

The SAPS's Crime Administration System (CAS) is the system used to register crime incidents for investigation, i.e. case dockets.30 The SAPS uses the terms 'complaints reported' and 'charges reported' interchangeably.31 When a criminal complaint is reported, a case docket is opened and allocated for investigation. A case docket can result in more than one charge being brought against a suspect (i.e. the accused, as soon as s/he is charged). The detection rate is based on charges, and calculated using the Crime Management Information System (CMIS), also known as the SAPS6. Data used by the CMIS are extracted directly from CAS.32

The detection rate is calculated as follows:

[(Number of charges referred to court for the first time during a reporting period) + (Number of charges withdrawn before court) + (Number of charges closed as unfounded)] divided by [(Number of charges reported) + (Number of charges brought forward from the previous reporting period)] x 100 percent.33

Detection rate for commercial crime

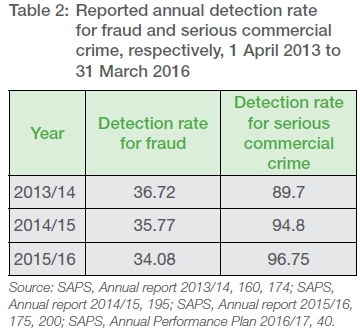

The SAPS does not report a detection rate for general, less serious commercial crime. However, it does report a detection rate for fraud (see Table 2).

Detection rate for serious commercial crime

The reported annual detection rate for serious commercial crime for the years 2013/14 to 2015/16 is listed in Table 2.

It should be noted that the detection rate for serious commercial crime is extremely high in comparison with the overall detection rate for less serious commercial crime (i.e. fraud overall). Scrutinising the reported detection rate for serious commercial crime reveals that the SAPS has likely calculated this indicator incorrectly and that its performance is in reality noticeably weaker. Although it is difficult to gauge the accuracy of the reported detection rate without the original data used by the SAPS, one can still get a good sense of it, using available public data.34

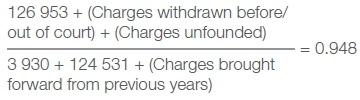

The detection rate for serious commercial crime is calculated as follows:

[(Number of charges referred to court for the first time, where a case represents at least one charge) + (Number of additional verifiable charges referred to court for the first time) + (Number of complaints withdrawn out of court) + (Number of complaints unfounded/false)] divided by [(Number of cases/complaints reported, where a new case represents at least one charge) + (Number of additional verifiable charges referred to court for the first time) + (Number of charges brought forward, where a case represents at least one charge)] x 100%.35 Using the above formula, one can substitute data from the SAPS Annual report 2014/15 as follows:36

Detection rate = 94.8% = 100% x [(Charges referred to court for the first time) + (Additional verifiable charges referred to court for the first time) + (Charges withdrawn before/out of court) + (Charges unfounded)] / [(New charges/ complaints reported) + (Charges brought forward from previous years) + (Additional verifiable charges reported)]

Whereas,

New charges/complaints reported = 3 930 (one case is equivalent to one charge)

Total charges referred to court for the first time = 126 953

Charges referred to court for the first time = 2 422 (one case is equivalent to one charge)

Additional verifiable charges referred to court = (126 953 - 2 422) = 124 531 for the first time

Total charges reported = 128 623 (sum of new charges reported and additional verifiable charges reported i.e. referred to court)

Therefore,

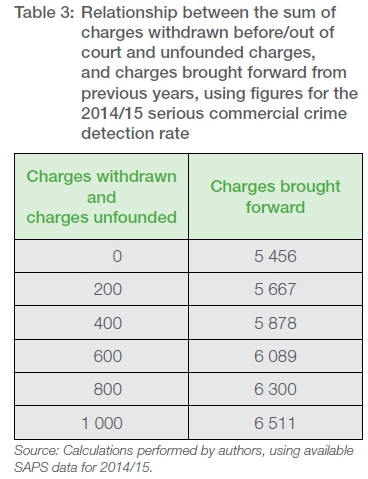

One can estimate the sum of the number of charges withdrawn before (out of) court and unfounded charges at between 0% and 100% of the new charges reported (3 930), since it is likely that the bulk of charges withdrawn and unfounded originate from new charges reported. Therefore, the number of charges brought forward from previous years is estimated to be between 5 456 and 9 601.37

While a total of 126 953 charges, linked to 2 422 cases, were referred to court for the first time during the period (i.e. an average of 52 charges per case docket), it is highly unlikely that the actual number of charges still under investigation brought forward from the previous year can be so low. What the SAPS is actually doing is substituting the number of case dockets brought forward with charges, where a docket is equal to a charge, while totally disregarding a large number of charges still under investigation, brought forward from previous years. To this end the SAPS acknowledges its own limitations and challenges insofar as the detection rate for serious commercial crime is concerned, stating that 'new cases reported cannot be kept accurately [sic] in terms of charges, since charges added to an accused in practice are only formulated months, even years, after the case is initially received ... in practice, charges are formulated when the investigation is completed and the state prosecutor formulates the charge sheet'.38

By implication it is impossible to keep accurate statistics relating to newly reported serious commercial crime. However, the SAPS fails to explain what happens as the investigation progresses and possible charges are identified and investigated. In reality, charges contemplated against a suspect are investigated over a period of time and are known to both the investigating officer and state prosecutor well in advance of compiling the charge sheet.39 However, these charges are not taken into account when calculating the detection rate before a suspect is charged. This results in an inaccurate detection rate, which does not reflect the actual detection capabilities of the SAPS across all outstanding charges still under investigation.

Although no raw data is available in respect of the serious commercial crime detection rate for 2015/16 (i.e. 96.75%), logic dictates that in order to achieve such a high performance, the raw figure for charges referred to court would have had to be in the same order as that of 2014/15 (probably between 126 000 and 130 000 charges). In 2015/16 a total of 3 776 new cases/charges were reported.40 It would be impossible to refer such a high number of charges to court from a relatively small pool of between 9 000 and 14 000 charges.41

Table 3 illustrates the relationship between the sum of charges withdrawn before/out of court and unfounded charges on the one hand, and, on the other, charges brought forward from previous financial years, based on a 94.8% detection rate and a number of 3 930 new charges reported (2014/15 figures).

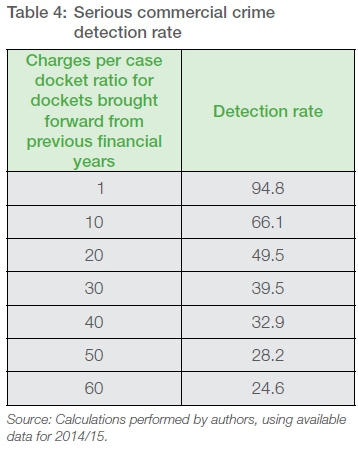

Based on a total of 1 000 charges withdrawn before/out of court and unfounded charges, the variation in the detection rate in relation to the number of charges linked per case docket brought forward from previous years, is shown in Table 4.

Table 4 is based on a total of 1 000 charges withdrawn before/out of court and unfounded charges against varying charges per docket ratio for cases brought forward from previous financial years.

Table 4 shows that as the charges to case docket ratio for cases brought forward ('old' cases) increases, the detection rate decreases against a fixed total for charges withdrawn before/out of court and unfounded charges (a sum of 1 000 in the example). The detection rate drops to as low as 32.9% if an average of 40 charges are investigated per docket brought forward. If one uses a ratio of 52 charges per case docket brought forward (i.e. the ratio of charges per docket referred to court for the first time in 2014/15) and entirely remove charges withdrawn before/out of court and unfounded charges from the formula, the detection rate would be as low as 30.8%, while the SAPS reports that it is 94.8%.42

A further challenge relates to the accuracy of SAPS data, for example in the 2013/14 financial year.43 During this period the number of new charges reported was 87 615, while the total number of charges referred to court for the first time was 83 913 (of which 3 417 were new charges referred to court for the first time on new cases). A total of 6 204 new cases were received for investigation. If one deducts this from the new charges reported (87 615), the number of additional verifiable charges referred to court for the first time should be 81 411. If the 3 417 new charges referred to court for the first time are deducted from the total charges referred to court for the first time (83 913), one should also get the number of additional verifiable charges referred to court for the first time. However, this calculates to 80 496 charges, which is different from the 81 411 calculated previously. The difference in these two figures raises doubts as to the accuracy of the data. Furthermore, it is not clear from the detection rate formula whether the additional verifiable charges reported or referred to court for the first time stem from the new charges/complaints (cases) reported, from charges brought forward from previous years, or from both.

Additionally, and as discussed earlier, the fact that the detection rate includes all complaints withdrawn before/out of court before anyone is charged, as well as unfounded complaints, contributes to an inaccurate reflection of the SAPS's performance in respect of serious commercial crime. This amounts to an irregular inflation of the detection rate, based on fictitious successes. Against the above backdrop it is argued that multiple significant inaccuracies can be found in relation to the detection rate for serious commercial crime as reported by the SAPS, and that the actual detection rate is much lower.44

Conclusion and recommendations

Despite limited successes achieved by law enforcement in combatting commercial crime, serious concerns exist over the lack of data available in the public domain to assess the performance of the SAPS in this regard, as well as the accuracy and trustworthiness of the serious commercial crime detection rate in particular. Burger, Gould and Newham make a valid point, stating that, from an analytical point of view, accurate and reliable crime statistics are needed to develop appropriate crime reduction strategies.45 Besides, inaccurate and unreliable statistics have negative effects, including an increase in public mistrust in the police, as well as an increased perception and fear of crime. Accurate, reliable and timely crime statistics enable members of the public to make informed decisions about their own safety and security, promote trust in the police and government, and encourage citizens to become involved in crime-prevention initiatives.46

The detection rate for all fraud is the lowest it has been in three years (34.08% in 2015/16), yet reported commercial crime has risen by about 3% since 2014/15. The actual serious commercial crime detection rate is estimated to be between 30% and 40% (based upon a charge to docket ratio of 30 to 40). Considering that the detection rate includes cases withdrawn by complainants, cases where prosecution has been declined, and unfounded cases, the SAPS needs to significantly improve its performance. Almost two-thirds of all reported commercial crimes go unsolved, and adding to this is the notable under-reporting of commercial crime incidents. Whichever way one looks at this, it is clear that the SAPS is not coping with commercial crime and is slowly but surely losing the battle. PwC reports that 70% of respondents interviewed regarded the SAPS as inadequately resourced and trained to deal with economic crime.47 The question should be asked as to why such a large percentage of respondents hold this view. What were their experiences in this regard and how can the situation be addressed or improved? The SAPS should take a hard look at its performance in this area and find appropriate measures to improve it. We propose an in-depth inquiry into the low detection rate and unsatisfactory impact of police efforts on these crimes, involving knowledgeable role players from the public and private sector to help find appropriate solutions. These could include training interventions, mentorship programmes, and the revision and updating of training material related to commercial crime investigations.48

In addition, we believe that the SAPS needs to address several issues:

• Under-reporting of commercial crime. The SAPS should develop and implement an access-controlled online reporting platform for commercial crime. Complaints that do not require investigation should be recorded using a simple one-page template (similar to the old 'crime chart'), instead of opening a docket. This should save time and costs spent on docket administration.

• Revision of formula for calculating the detection rate of crime. The current formula should be amended to exclude those complaints withdrawn before/out of court and unfounded complaints in respect of which a certain amount of actual investigation has not been done. Only complaints where the investigation has reached a reasonably advanced stage should be included in the detection rate. This will enhance the trustworthiness and reliability of crime statistics and provide a more accurate picture of reality.

• Discrepancy in data for fraud/commercial crime detection rate. An independent audit of SAPS statistics is proposed to determine reasons for the differences in reported fraud and commercial crime figures from annual crime statistics and annual reports, as published by the SAPS on its website.

• Inaccurate detection rate for serious commercial crime and lack of sufficient data. The CAS should be adapted to enable users to capture large numbers of charges against a suspect in an efficient manner. Performance management systems for commercial crime should include all charges under investigation brought forward from previous financial years when calculating the detection rate. If statistics relating to charges referred to court can be kept, it should be plausible to do the same for charges still under investigation. The use of manual statistical systems should be phased out and only computerised systems allowed (CAS and CMIS). The SAPS should also publish all raw data used during calculations.

• Improving commercial crime statistics.

A comprehensive breakdown in this regard should be published at least twice a year to include different crime types/categories, modus operandi trends, victims/targets, and geographical incidence of crimes. The same should be done for cases reported as 'other fraud' under serious commercial crime. We argue that in order to effectively combat commercial crime, law enforcement should maintain an accurate, reliable regime of regular crime threat and crime pattern analyses, designed to review, adapt and strengthen crime-fighting strategies.

In conclusion, we advocate more accurate, reliable, timely and comprehensive commercial crime statistics that should be made available to relevant role players who can assist to assess problem areas and develop effective combatting strategies. This should strengthen efforts to combat these crimes across the commercial crime landscape.

Notes

1 National Anti-Corruption Forum, Towards an integrated national integrity framework: consolidating the fight against corruption, Report on the Third National Anti-Corruption Summit, 2008, 86-89, http://www.nacf.org.za/anti-corruption-summits/third_summit/United_Nations_Report_third_summit_2008.pdf (accessed 22 September 2016); S Kranhold, Collusion, cartel, price fixing, who will be next?, BDO South Africa, 24 August 2016, https://www.bdo.co.za/en-za/insights/2016/mining/collusion-cartel-price-fixing-who-will-be-next (accessed 19 March 2017); P Sidley, South African drug companies are found guilty of price fixing, the bmj, 23 February 2008, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2249668/ (accessed 19 March 2017); N Seria, Tiger Brands admits to bread price-fixing, pays fine, Moneyweb, 13 November 2007, https://www.moneyweb.co.za/archive/tiger-brands-admits-to-bread-pricefixing-pays-fine/ (accessed 19 March 2017).

2 G Cliff and C Desilets, White collar crime: what it is and where it's going, Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy, 28, 2014, 48-523. [ Links ]

3 Ibid., 483-484.

4 J Braithwaite, White collar crime, Annual Review of Psychology, 11, 1985, 1-25; [ Links ] W Tupman, The characteristics of economic crime and criminals, in B Rider (ed.), Research handbook on international financial crime, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015, 3-14; [ Links ] GA Pasco, Criminal financial investigations, 2 edition, Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2013, 101; [ Links ] International Monetary Fund (IMF), Financial system abuse, financial crime and money laundering, Background Paper, 12 February 2001, 3-6, 20, https://www.imf.org/external/np/ml/2001/eng/021201.pdf (accessed 4 February 2017); Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), What we investigate: white-collar crime, https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/white-collar-crime (accessed 12 October 2016); FBI, Financial crimes report 2010-2011, 1-5, https://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/financial-crimes-report-2010-2011 (accessed 5 February 2017); PricewaterhouseCoopers, Economic crime: a South African pandemic, Global Economic Crime Survey 2016, 5 South African edition, 1, https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/south-african-crime-survey-2016.pdf (accessed 21 November 2016); South African Police Service (SAPS), Annual report 2013/14, 160, 174; SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 204; SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 175; SAPS, Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI), Commercial crime mandate, 2010.

5 Ibid.

6 SAPS, Annual report 2013/14, 160, 174; SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 204; SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 175; SAPS, DPCI, Commercial crime mandate; SAPS, Performance information management framework 2016/17, 114, http://www.saps.gov.za/about/stratframework/strategic_plan/2016_2017/technical_indicator_description_2016_2017.pdf (accessed 22 November 2016).

7 Ibid. The SAPS's distinction between serious commercial crime and general, less serious commercial crime apparently arises from the relevant regulatory framework provided in terms of the South African Police Service Act 1995. The DPCI was established to prevent, combat and investigate national priority offences, in particular serious organised crime, serious commercial crime and serious corruption (Section 17B and 17C). Its functions (Section 17D) are to prevent, combat and investigate selected national priority offences (Section 16[1]), corruption-related offences and offences or categories of offences referred to it by the national commissioner, all subject to policy guidelines issued by the minister of police and approved by Parliament in terms of Section 17K(4) ('Policy guidelines'). Also see Helen Suzman Foundation v President of the Republic of South Africa and Others ; Glenister v President of the Republic of South Africa and Others [2014] ZACC 32; Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, Revised 2015 policy guidelines for the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigations (DPCI), 23 July 2015, http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/150818dpci.pdf (accessed 22 November 2016); Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMG), Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI): mandate and activities, 17 September 2014, https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/17552/ (accessed 22 November 2016).

8 SAPS Annual report 2015/16, 161, 169, 198, 200.

9 Ibid., 200.

10 Informal discussion, senior SAPS member (A) attached to the DPCI, 15 September 2016; Personal interview, senior SAPS member (B) attached to the DPCI, 19 September 2016.

11 Defence Act 2002 (Act 42 of 2002); Independent Police Investigative Directorate Act 2011 (Act 1 of 2011); South African Revenue Service (SARS), SARS and the criminal justice system, 2016, http://www.sars.gov.za/TargTaxCrime/WhatTaxCrime/Pages/SARS-and-the-Criminal-Justice-System.aspx (accessed 4 January 2016); Special Investigating Units and Special Tribunals Act 1996 (Act 74 of 1996); Special Investigating Unit (SIU), Annual report 2013/14, 9-23; SIU, Annual report 2014/15, 17-20; SIU, Annual report 2015/16, 22-36; National Prosecuting Authority Act 1998 (Act 32 of 1998); Public Protector Act 1994 (Act 23 of 1994); Competition Act 1998 (Act 89 of 1998); National Credit Act 2005 (Act 34 of 2005); Consumer Protection Act 2008 (Act 68 of 2008); Financial Services Board Act 1990 (Act 97 of 1990); Financial Markets Act 2012 (Act 19 of 2012); Friendly Societies Act 1956 (Act 25 of 1956); Inspection of Financial Institutions Act 1998 (Act 80 of 1998); Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act 2002 (Act 37 of 2002); Collective Investment Schemes Control Act 2002 (Act 45 of 2002); Banks Act 1990 (Act 94 of 1990); South African Revenue Service Act 1997 (Act 34 of 1997); Tax Administration Act 2011 (Act 28 of 2011); Agricultural Produce Agents Act 1992 (Act 12 of 1992); Co-operatives Act 2005 (Act 14 of 2005); International Trade Administration Act 2002 (Act 71 of 2002); Marketing of Agricultural Products Act 1996 (Act 47 of 1996); Counterfeit Goods Act 1997 (Act 37 of 1997); Merchandise Marks Act 1941 (Act 17 of 1941). Other institutions and office bearers that may be able to assist with specific types of commercial crime investigations include counterfeit goods inspectors, cyber inspectors, the Road Accident Fund (RAF), the National Gambling Board (NGB) and provincial gambling boards, the National Lotteries Commission, the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), the Office of the Pension Funds Adjudicator, the South African Post Office and the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC).

12 SAPS, Annual report 2013/14, 160, 174; SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 204; SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 175.

13 SAPS, Annual report 2013/14, 160; SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 175.

14 Of these 69% were fraud cases (see SAPS, Annual report 2013/14, 174, 178-179).

15 SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 224, 225.

16 SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 202, 204.

17 Over the three-year period from 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2015 fraud made up 66% of these cases.

18 SAPS, Crime statistics 2015/16, http://www.saps.gov.za/services/crimestats.php (accessed 21 November 2016).

19 SAPS, Annual report 2013/14, 107, 178.

20 SAPS, Crime statistics 2015/16.

21 PricewaterhouseCoopers, Economic crime.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Statistics South Africa, Victims of crime survey 2014/15, 66, 88, https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0341/P03412014.pdf (accessed 23 October 2016); Statistics South Africa, Victims of crime survey 2015/16, 69, 93, http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0341/P03412015.pdf (accessed 19 March 2017). The reporting rate for 2014/15 in respect of consumer fraud is provided as 26.8% in the 2014/15 survey, yet it is reported as 27.2% in the 2015/16 survey.

25 J Burger, C Gould and G Newham, The state of crime in South Africa, South African Crime Quarterly, 34, December 2010, 10-11. [ Links ]

26 SAPS, Performance information management framework 2016/17, 78.

27 SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 198-201; SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 169-170.

28 SAPS, Performance information management framework 2016/17, 80.

29 SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 200. The SAPS (usually a detective branch commander or unit commander at an investigation unit) assesses the complainant's statement and other information/evidence. This can happen at the start of the investigation (preliminary investigation stage) or later during the investigation. If the SAPS believes that it is clear that a legal element or elements of a crime is/are missing and that no crime has been committed, the case is closed as unfounded. In some cases the SAPS will approach the prosecuting authority to decline prosecution. Those cases are then closed as withdrawn before court.

30 Ibid., 198-201.

31 SAPS, Performance information management framework 2016/17, 80-81; SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 198-201; SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 169-170.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 On 26 September 2016 a formal request was submitted to the SAPS in terms of the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2000 (Act 2 of 2000) to obtain more comprehensive raw data in respect of the detection rate for serious commercial crime for the period 2012/13 to 2015/16. Despite various follow-up enquiries, the SAPS has provided neither the requested data nor any reason for refusing to provide same (the request is deemed to have been refused in terms of the act). A subsequent appeal was lodged in terms of the act but no outcome has so far been received. The request and appeal were also submitted to the DPCI at national level but to no avail. It was established that the requested figures are readily available from the national head, Serious Commercial Crime, DPCI.

35 SAPS, Performance information management framework 2016/17, 114.

36 SAPS, Annual report 2014/15, 221.

37 Calculations performed by the authors. The detection rate only takes into account charges that are under investigation and not pending in court. Charges already on the court roll, even though they might still be investigated, are not counted for the detection rate.

38 SAPS, Performance information management framework 2016/17, 114. Factors that are cited as having a negative influence on the SAPS's ability to keep accurate statistics in respect of serious commercial crime charges include the extent and complexity of serious commercial crime cases and the duration of investigations (large cases can take several years to finalise).

39 Prosecutors and SAPS investigating officers dealing with serious commercial crime cases work together in terms of a prosecutor-guided investigation (PGI) methodology, whereby they cooperate to form a joint investigation and prosecution team for the duration of the case. This is to ensure more efficient investigations and prosecutions in complex and voluminous cases. National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), Annual report 2015/16, 22.

40 SAPS, Annual report 2015/16, 200-204.

41 This is the charges reported for 2015/16 rounded off to 4 000 and added to the 'charges' brought forward to 2014/15, rounded off to between 5 000 and 10 000.

42 Even if one calculated the detection rate using a 'best possible scenario' approach by:

• Including a sum total of 1 000 charges withdrawn before/ out of court and unfounded charges,

• The lowest possible number of charges brought forward from the previous year (5 456), and

• A charges to case docket ratio of 10 for dockets brought forward from the previous year, the serious commercial crime detection rate for 2014/15 would be 69.9%.

43 SAPS, Annual report 2013/14, 174, 178-179.

44 In addition to the SAPS's inaccuracies pointed out in respect of serious commercial crime, it must also be taken into account that the average rate of error for SAPS crime statistics is said to be between 10 and 11%, as was testified before the Khayelitsha Commission of Enquiry. Statistical errors include incorrect classification of crimes on the Crime Administration System (CAS), the failure to capture multiple charges (counts) in dockets and the failure to register cases on CAS. What makes the situation worse is that the SAPS manual on crime definitions and crime codes used for the registration of case dockets on CAS, in respect of commercial crime, only includes corruption, theft by false pretences, fraud, forgery and uttering. This means that all other types of commercial crime are classified and registered under incorrect crime codes on CAS, which leads to incorrect crime statistics. A US study conducted by the research company Rand Corporation between 1973 and 1975 on the organisation and effectiveness of the criminal investigation fraternity in the US found that about 30% of indexed arrests were made by first responders to crime scenes (e.g. patrol officers). In about 50% of cases the identity of the perpetrator was supplied by victims or witnesses. The remaining 20% of arrests were made by investigating officers, of which only about 3% can be attributed to actual investigative efforts that led to the identification of suspects. The authors, who are both former investigators and members of the Commercial Crime Unit (CCU) of the SAPS, suggest that a similar pattern can be found in South Africa today in respect of commercial crime cases and, likely, other crime types too. From many years of practical experience in the CCU, we suggest that a significant number of arrests are made by uniformed members responding to complaints, security personnel or members of the public and that the charges subsequently referred to court are included in the numbers used to calculate the detection rate. Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry, Towards a safer Khayelitsha: report of the Commission of Inquiry into allegations of police inefficiency and a breakdown in relations between SAPS and the community of Khayelitsha, August 2014, 62, http://www.khayelitshacommission.org.za/images/towards_khaye_docs/Khayelitsha_Commission_Report_WEB_FULL_TEXT_C.pdf (accessed 11 July 2017); SAPS, Crime definitions (2012) to be utilized by police officials for purposes of the opening of case dockets and the registration thereof on the Crime Administration System, National Commissioner's reference 45/19/1 dated 2011/11/07, 35-58, 201, 210-214; Peter W Greenwood, The Rand Criminal Investigation Study: its findings and impacts to date, Rand Corporation, July 1979, 2-3, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2008/P6352.pdf (accessed 11 July 2017).

45 Burger, Gould and Newham, The state of crime in South Africa, 10-11.

46 The availability of official crime statistics has improved somewhat with the announcement in 2016 that these would now be released both quarterly and annually, while the figures for the first three quarters of 2016/17 were released in March 2017. In addition to this, Statistics South Africa also releases an annual victims of crime survey T Gqirana, Crime stats to now be released quarterly, News24, 9 June 2016, http://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/crime-stats-now-to-be-released-quarterly-radebe-20160609 (accessed 11 July 2017).

47 PricewaterhouseCoopers, Economic crime, 1.

48 Reyes also proposes a number of useful tactical measures to improve the efficiency and solving rate of criminal investigators, including a proper case management system that can be used to monitor performance outputs as well as time management. See R Reyes, Tactical criminal investigations: understanding the dynamics to obtain the best results without compromising the investigation, Journal of Forensic Sciences and Criminal Investigation, 2:2, 15 March 2017. [ Links ]