Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SA Crime Quarterly

On-line version ISSN 2413-3108

Print version ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. n.55 Pretoria Mar. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/v0n55a46

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Comfortably cosmopolitan? How patterns of 'social cohesion' vary with crime and fear

Anine KrieglerI; Mark ShawII

IResearcher with the Centre of Criminology at the University of Cape Town. She holds MA degrees from both the University of Cape Town and the University of Cambridge, and is a doctoral candidate in Criminology. anine.kriegler@gmail.com

IIDirector of the Centre of Criminology at the University of Cape Town. He holds the NRF Chair in African Justice and Security and is the director of the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. Mark worked for 12 years at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). mark.shaw@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Achieving 'social cohesion' across race and class divides in South African settlements is a major challenge, given the divided urban geography of apartheid. Cosmo City, a new mixed-use settlement north-west of Johannesburg, was conceived and designed for social inclusion and cohesion, albeit between people of different income levels rather than race groups. A number of the development's spatial features were also thought likely to reduce crime and fear of crime, either directly or as mediated by stronger social cohesion. A survey was conducted among 400 Cosmo City households to determine the extent of community cohesion, fear of crime, and rates of crime victimisation. Results found a strong sense of localised community pride and belonging within immediate neighbourhoods, and relatively high feelings of safety. However, self-reported crime victimisation rates did not suggest that there had been a crime reduction effect - in fact, they were extremely high. This may be a surprising but not unprecedented outcome of strong social cohesion, which may allow knowledge of crime incidents to spread through community networks as a shared sense of victimisation and thus raise the likelihood of survey reporting above the real rate of crime incidence. Further research should test whether, regardless of any impact on crime itself, greater social cohesion may reduce fear of crime even while raising a perception of crime rates. Policy and design that successfully promote social cohesion but fail to reduce crime may exacerbate a perception of victimisation.

Social cohesion in theory and practice

An interest in the significance of the neighbourhood, of shared space, values and a sense of community naturally has a long history in social theory and policy.1

Developments at various points in the last century have driven waves of heightened concern about the perceived growth in individualism, competition and anomie, and about the tangible and intangible common goods lost as a result. At the same time, in many places global mobility and the perception of increasing diversity have raised anxieties about multiculturalism and integration, and about what it takes to build and sustain meaningful, effective communities.2

One of the key concepts to have emerged through these various iterations of theory and research on the role of the collective is that of 'social cohesion'. Social cohesion has been a buzzword for roughly the last two decades,3 but like many of its aligned concepts (such as 'social disorganisation', 'social capital', 'collective efficacy' and even 'neighbourhood') it has been plagued throughout by debates about its conceptual robustness and meaning.4 As others have done,5 this article opts for a fairly loose definition of social cohesion, as representing the sense of community among and level of interaction between residents in the area under consideration.

A range of conceptual and research approaches have found that the strength of social ties is related to other social outcomes, including patterns and feelings of crime and safety. In one direction, the functioning of community ties and spaces is affected by crime and the fear of crime, which can lead people either to restrict their involvement in public spaces and activities and to wall themselves in, or to unite against a shared danger.6 In the other direction, social norms such as willingness to intervene for the public good and informal monitoring and guardianship of spaces have been shown to exert downward pressure on crime.7Further, community factors, including social cohesion, have been shown to shape assessments of risk and fear of crime, regardless of their impact on crime itself.8 This research is complicated by the fact that many of the demographic and social variables that affect social cohesion (including poverty, population turnover, and racial/ethnic diversity)9 also affect crime and fear directly.10

There are also ways in which the built environment is thought to help facilitate social cohesion. Design for cohesion includes factors such as encouraging mobility and accessibility to various means of transport, promoting multi-functionality of public spaces, drawing people of diverse backgrounds to share the same services and facilities, and maximising feelings of comfort and safety.11 These and other elements of the built environment, such as the 'defensibility' of space and signs of neglect, have in turn also been shown to have a direct impact on both crime12 and fear of crime.13

To further complicate the picture, research has shown that there are often surprisingly weak relationships between fear of crime, perception of the risk of crime, and actual crime victimisation rates, because the information we receive about crime is filtered through various personal and social lenses.14 The perception of the amount of crime and fear of crime also involve separate components of the cognitive and emotional responses to crime.15 There is by no means a clear one-to-one relationship between the various components of the objective and subjective experience of crime.

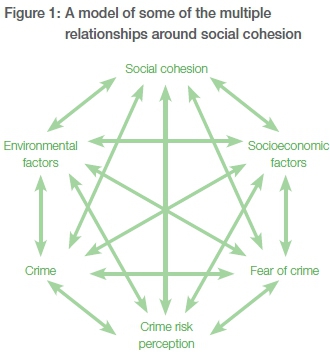

Ultimately, there is a web of relationships between social cohesion, socioeconomic variables, characteristics of the built environment, crime levels, the perception of crime risk, and fear of crime. These interrelationships suggest the need for a complex and reflexive model, for example as portrayed in Figure 1.

The literature clearly indicates that tensions can be expected between social cohesion and diversity. For all that the harms of segregation have been well demonstrated, and that integration may be desirable for achieving various social ends, a large body of evidence suggests that spaces (ranging in size from neighbourhoods all the way through to countries) that have more ethnic, racial and socioeconomic diversity find it considerably more difficult to form cooperation, trust and social cohesion.16 Social ties and a sense of community are easier to build with people who seem similar to us.17 This is the case not just for race or ethnicity, but also for wealth. Inequality compromises the development and maintenance of social cohesion,18 even as an appeal to social cohesion can mask issues of inequality by stressing values and togetherness rather than the correction of concrete inequalities.19 Overall, the success of attempts to increase social utility on various measures through the creation of socio-economically mixed environments worldwide has been equivocal.20

South Africa's divided spaces

Inequality, difference and segregation are chronic South African concerns, to the point where it is not clear whether the 'South African society' can really be said to exist at all - that is, whether values and space are sufficiently shared to allow it all to meaningfully hold together.21 Even by the standards of many developing countries, South African cities are massively fragmented. Apartheid policy not only enforced rigid segregation by race but also effectively drove the poor to the urban peripheries, making for long and expensive commutes between work and home, and a vicious cycle of poverty and exclusion.22 Income inequality in the major metros is extremely high,23 such that there are hard-to-climb 'income cliffs' between socioeconomic levels and their associated spaces.24 The result is a system of tightly overlapping inequalities of race, space, wealth, opportunities, services, health and so on, which in turn undermines attempts at promoting growth, development and legitimacy.25

The post-apartheid government has made considerable progress towards providing low-cost homes to the huge backlog of people without formal housing, but the urgency of the task has meant that quantity has largely taken precedence over quality, with subsidised housing still mostly being built on the urban peripheries and in economically and socially unsustainable forms.26Major new residential developments of the last 20 years have tended to fall into one of three clear categories: fully subsidised (e.g. Reconstruction and Development Programme [RDP]) housing areas; informal settlements; and relatively affluent 'gated communities' built by private developers.27 This has contributed to the fact that many neighbourhoods remain highly internally homogeneous.28

The importance of more 'integrated', 'inclusive' or 'mixed' housing (incorporating a range of housing types, sizes and prices in close proximity)29 has long been acknowledged in policy and law, but fiscal and bureaucratic constraints and the market for land have been chief among the numerous challenges to widespread implementation. However, in Johannesburg's north-west region, near Roodepoort and Fourways, a public-private partnership was formed and successfully built a new mixed-income, mixed-use settlement known as Cosmo City.

This area is located geographically and conceptually at the forefront of post-apartheid urban developments. It has seen massive growth since the mid-1990s, such that living in a new development is the norm here.30 It has become emblematic of the new housing model that is neither township nor suburb,31 but instead takes the form of 'complexes', 'estates' and 'gated communities'.32 These spaces take a range of different characters, usually with distinct class niches and architectural styles, but all are marked by their privatised and collectivised approach to governance, which has managed to bring white and black South Africans to a shared sense of middle-class urban citizenship rarely seen elsewhere.33

In Cosmo City this model of private, middle-class governance has been fused with the more traditional approach of state-provided housing for the poor. It was built with the explicit aim of having people of diverse backgrounds and income levels (but not racial groups) live in close proximity and share space and facilities. As such, it offers a unique case study for the concept of social cohesion. This research sought to determine the degree to which this new development has succeeded in fostering a sense of community, as well as what this might mean for levels and fear of crime.

Building a diverse, cohesive community

In 2000/2001, a partnership known as CODEVCO was developed between private real estate developer Basil Read, a black economic empowerment consortium called Kopano, the City of Johannesburg as landowner, and the Gauteng provincial government as subsidy provider. CODEVCO undertook, following a court order, to house the residents of the informal settlements of Zevenfontein and Riverbend who were illegally occupying private land, and to do so by developing an inclusive and sustainable residential and commercial space for people of mixed incomes and backgrounds. The development was granted 1 105 hectares of formerly privately-owned farm land. Following years of legal challenge from residents of the relatively affluent surrounding areas, who claimed that the development would harm their property prices,34 building work started in earnest in January 2005. The first beneficiaries moved in by the end of that year, and residential building was completed in 2012. All roads are tarred, all units have in-house water supply, water-borne sanitation and pre-paid electricity, and a large number of units are also fitted with solar geysers.35 The private developers have gradually handed over maintenance responsibility to the City, but continue to play an active role in some aspects of governance.

The formal population in Cosmo City as of 2015 is estimated at around 70 000 people, but the number living in backyard sublets is unknown, such that the total population may be closer to 100 000.36 The development is mixed in that it comprises 5 000 low (or no) income, fully subsidised RDP houses; 3 000 somewhat larger, credit linked, partially subsidised houses; 3 300 even larger, privately bonded, open market houses; 1 000 rental apartment units; plus schools, parks and recreation sites, commercial, retail and industrial sites, and a 300 hectare environmental conservation zone that runs through the development. It was anticipated that household incomes would vary between less than R3 500 per month in the RDP section to more than R15 000 in the privately bonded houses.37

The mixed profile, including lower-income and lower middle-class residents, was intended to make the development economically and socially sustainable and inclusive. It was envisioned that residents of different income levels would be able to send their children to the same local schools, to shop in the same retail areas, and to use the same recreation spaces. Key to this ideal of shared spatial use in Cosmo City is what is known as the Multi-Purpose Centre, a central cluster of buildings that include an events hall, a skills centre, a library, a gym and various sports fields. The developers have also attempted to foster a sense of community pride and cohesion through co-sponsoring an annual garden competition, assisting with the setting up of residents associations, providing all new residents with an information pack with details on what is expected of them and who to contact for service delivery issues, and setting up a local newspaper called the Cosmo Chronicle to spread information and report on local news.38

The residential areas are divided into small, distinct neighbourhoods or 'extensions', each with a typical housing size and design, with many streets shaped as crescents and culs-de-sac - all with the goal of creating a village-like character.39 These residential clusters (which correspond with different housing classes) are scaled internally for pedestrians, but are separated by tracts of open land and conservation areas.40 Although not access controlled like many of the more upmarket developments nearby, it is self-contained, so that few people entering it are just passing through, and there is a clear delineation separating it from surrounding areas. Streets are named in common theme after countries, states and cities from around the world, and (with a hint of the Orwellian) residents sometimes call each other Cosmopolitans. Many of these features of Cosmo City's built environment hope to help facilitate social cohesion. On the other hand, its goal of condensed socioeconomic diversity provides certain challenges.

Diversity achievement

The 2011 national census was fielded before Cosmo City had been completed (reflected in the fact that it counted a total of just 44 292 residents), but its results do suggest that Cosmo City has achieved something unusual in its vicinity. Some rough comparison is possible between its ward (of which it made up more than 80% of the population), the ward that covers the greater part of the nearby township of Diepsloot, and the ward that includes Honeydew, the Eagle Creek Golf Estate and many of the other complexes described in other research on this region, for example by Duca and Chipkin.41 The Cosmo City ward's residents' average household income is about double that of greater Diepsloot (which is close to the national average) but a quarter of that in the Honeydew area. It also has a considerably higher proportion of people employed (62%) than in Diepsloot (55%), but lower than in Honeydew (77%).42 About 14% of its residents have completed education past grade 12, as compared to about a third in Honeydew and less than 2% in Diepsloot. But rather than simply finding itself between these socioeconomic spaces, Cosmo City does to some extent seem to straddle them. As demonstrated in Figure 2, it shows a relatively wide and even spread through the income brackets, whereas Diepsloot skews far more sharply and poorer, and Honeydew skews more sharply and wealthier.

This does suggest that the development has been successful in creating a more mixed-income residential profile than have some of its key neighbours. There are other signs of relative diversity. Almost 75% of Honeydew's residents speak primarily either English or Afrikaans, compared to 3% in Diepsloot and 13% in Cosmo City. In the Honeydew ward, the 2014 national vote went to the Democratic Alliance (DA) by a landslide. The landslide in in the Diepsloot ward went to the African National Congress (ANC) , with the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) well behind and the DA barely showing. The ANC had a smaller but still comfortable majority in Cosmo City's ward, but here the EFF and DA were almost tied in their share of the rest of the vote.43Although less so than Diepsloot, Cosmo City also has greater concentrations of people who were born outside Gauteng and outside South Africa than the Honeydew profile and the Johannesburg average. According to Johannesburg's Customer Satisfaction Survey data, about half of the 119 randomly selected Cosmo City ward residents polled had had a brick or concrete house as their previous dwelling before moving to Cosmo City, 26% had lived in an informal dwelling in an informal settlement, and 12% in an informal dwelling in the backyard of a formal dwelling.44

However, the promotional documents and interviews with the private and city role players suggest that racial or ethnic diversity never featured in the inclusiveness goals or outcomes for Cosmo City.45The overwhelming majority of Cosmo City residents are still the 'previously disadvantaged'.46 It is over 97% black African, less than 1% coloured, and less than 0.5% white or Indian and Asian respectively.47This is little different from its directly neighbouring informal settlements or from Diepsloot, and considerably less mixed than the Honeydew ward and Johannesburg as a whole, as demonstrated in Figure 3 (overleaf).

All told, Cosmo City does seem to be remarkably more mixed than at least some of its more traditional neighbouring areas in terms of income level and some other socioeconomic and political indicators, but not at all mixed in terms of population group. As such, it is at best an incomplete model of how post-apartheid inclusion and integration might be envisioned for the city or country more broadly. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating case study on community diversity, social cohesion and their impact on crime and fear.

Research method

The South African Cities Network (SACN) commissioned the Centre of Criminology at the University of Cape Town to produce a number of outputs on different aspects of the state of crime and safety in South African cities. One component of this larger project was to determine the extent of social cohesion in Cosmo City - as evidenced in a sense of community belonging and pride, the level of interaction between people of different backgrounds, and the extent of fear of crime and level of crime victimisation. Reported crime figures could only be obtained from the South African Police Service (SAPS) for the entire Honeydew policing sector, within which Cosmo City falls. The SAPS refused access to crime figures specifically for the Cosmo City part of the sector, on the grounds that any crime statistics released to the public must first be tabled in Parliament, and that this was not done on such a small geographic scale.

Vibrand Research, a market research agency that uses mobile phones to capture the results of face-to-face interviews, was commissioned to complete a survey. The survey was administered to 400 Cosmo City households from 6 to 9 May 2015. The sample consisted of 133 households in fully subsidised housing, 80 in credit-linked units, 27 in rental apartments, 88 in bonded housing, and 72 in backyard sublets. These proportions were selected to correspond with the proportions of housing types as they appear in the area, with the likely exception of the backyard sublets, of which the number of units or residents is unknown, and for which the correct sample size was therefore necessarily speculative. The sample's gender split was approximately equal, and the race composition roughly in line with that estimated for the area in Census 2011.

A total of 25 questions were asked, covering demographic identifiers, income, perceptions of and responses to crime and policing, rates of crime victimisation, community pride, and so on. Responses were immediately captured and transmitted via mobile phones. Of this data, only those survey items that have a clear bearing on social cohesion, perceptions of safety and levels of self-reported crime victimisation have been extracted for discussion here. Unfortunately, although adequate to give a general indication, the data set does not make it possible to properly test the associations, never mind a model of the complexity proposed in the introductory section above. As such, this is not a perfect test of social cohesion48 or its association with crime perceptions and victimisation, but it is a first descriptive step towards revealing how these dynamics may be playing out in this highly unusual neighbourhood. Its mobile format precluded matching the question structures directly, but for context and where possible, comparisons are made between the results of this survey and those of the National Victims of Crime Survey.

Measuring social cohesion

In order to get a sense of how much social cohesion respondents experienced in Cosmo City, they were asked:

• To what extent do you feel part of the community in the part of Cosmo City where you live [street, neighbourhood, extension]?

• To what extent do you feel part of the community in the whole of Cosmo City?

• Are you proud to be a resident in Cosmo City?

• How many of the people you interact with in Cosmo City have a similar background to you?

• How would you describe your interaction with other people who live in Cosmo City?

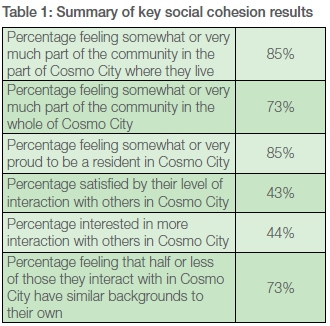

More than 85% of the respondents said they felt at least somewhat part of the section of community where they live - that is, their own street, neighbourhood or extension. Less than 10% did not really think about it or care, and 5% did not much or at all feel part of their immediate community. About 73% of respondents said they felt at least somewhat part of the community of the whole of Cosmo City. The proportion who did not much feel part of the greater Cosmo City community, at about 7%, was slightly higher than that for the respondents' immediate community, and the proportion who did not really think about it or care was about double that for the immediate community, at 20%. In the absence of survey replication or other suitable comparison, it is of course difficult to determine exactly how much better or worse Cosmo City is doing on social cohesion than other areas. Nevertheless, the findings here suggest a significant degree of 'community' and 'pride' in Cosmo City, and more so in immediate neighbourhoods than in the development as a whole. Cohesion at one level does not necessarily imply cohesion at another,49 and indeed it is never clear what level of geographic aggregation is most appropriate in testing neighbourhood effects such as social cohesion.50

That people should identify more with the smaller neighbourhood in which they live than with the large development as a whole is not surprising, but it may suggest a measure of caution in the extent to which social cohesion and integration are stretching across socioeconomic boundaries. It may well be that relations are good within each housing type area, but that there is relatively little interaction between, say, the poorer residents who live in the fully subsidised units and the relatively affluent who live in privately purchased houses. So it is that Cosmo City has been described as being less about mixed housing than about combined housing, with the different housing types and associated classes living apart in separate neighbourhoods even as they share the name of Cosmopolitans.51

Eighty-five percent of the respondents said they felt at least somewhat proud to be a resident in Cosmo City, and 57% said they felt very proud. Although the immediate neighbourhood clearly has more significance in terms of belonging, the proportion of residents who reported feeling part of and proud of the entire community is high.

About 74% of respondents said that at least half of the people they interact with in Cosmo City have different backgrounds to their own. At the same time, about 43% were satisfied with the level of interaction they had with other people who live in Cosmo City, and a further 44% were interested in interacting more. Only 13% expressed no interest in interaction. This is a positive sign, given the large proportion saying that those they interact with in Cosmo City mostly have different backgrounds to their own. These are encouraging indications of good social cohesion, especially given that Cosmo City is still so new.

Crime and fear of crime

To determine the extent of their crime victimisation and fear, respondents were asked:

• How are you most affected by crime in Cosmo City?

• What crimes have the members of your household experienced in Cosmo City in the last five years? The response options were:

• Theft of personal property

• Mugging/robbery in public space

• Theft of a car/motorbike/bicycle

• Car hijacking

• Home burglary

• Home robbery

• Business burglary or robbery

• Physical assault

• Sexual assault/rape

• Murder

• Other

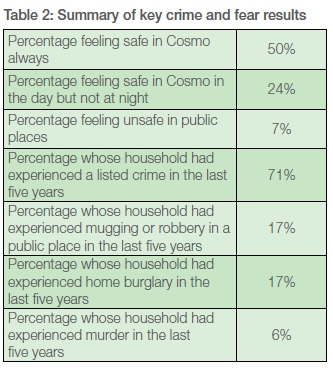

About 74% of respondents said they feel safe in Cosmo City, at least during the day. According to the Statistics South Africa National Victims of Crime Survey for 2014/2015, about 85% of South Africans say they feel safe walking alone in their area during the day.52 On the other hand, about half of respondents here said they feel safe in Cosmo City all the time, while about 69% of respondents to the National Victims of Crime Survey said they felt unsafe walking alone in their area at night - and by implication no more than about 31% could say that they felt safe at all times.53 Only 7% of Cosmo City respondents felt unsafe in public places, as compared to 37% of National Victims of Crime Survey respondents nationally who said that fear of crime leads them to avoid going to open spaces unaccompanied.54 The questions in the two surveys are not perfectly comparable, but there is some indication that Cosmo City residents are less fearful of crime than the national average.

Seventy-one percent of the respondents said that the members of their household had experienced at least one of the listed crime types in the last five years. Six percent said that someone in their household had been murdered in the last five years. This would imply a murder rate about 15 times that of the official police statistics in the precinct - especially implausible given the evidence that murder is relatively well reflected in official statistics.55 But rare and particularly memorable crimes like murder are often massively over-represented in victim surveys, and indeed their numbers are also implausibly inflated in the National Victims of Crime Survey.56

Rates for a number of the other crimes reported are also considerably higher than those in the National Victims of Crime Survey. The self-reported rate of theft of personal property in Cosmo City is about 30% in five years, or about 6% a year, as compared to the National Victims of Crime Survey result of 2% a year. Some other crimes see Cosmo City self-reporting rates more in line with those seen in the National Victims of Crime Survey. The framing and phrasing of the questions do not make for a perfect methodological match, but the overall suggestion is that self-reported rates of crime victimisation in Cosmo City appear to be considerably higher than the national picture, some improbably so.

Conclusion: knowing your neighbour, knowing their crime

It is unclear to what extent crime victimisation is indeed more common in Cosmo City, although Honeydew police are quoted in the press as suggesting that Cosmo City has a disproportionate share of the crime in the sector, itself one of the highest crime areas in Johannesburg.57 It is also unclear to what extent the survey conditions or community characteristics, including social cohesion, may have influenced the respondents' inclination to self-report these crimes. An overwhelming proportion of respondents reported having experienced some form of crime, a very large proportion reported strong social cohesion, and a small proportion reported much fear. The unexpectedly limited variation in responses and the relatively small sample size make it impossible to reliably ascertain a relationship between these factors. It is noteworthy, however, that there is certainly no evidence that the apparently strong social cohesion has resulted in a low crime rate.

The self-reported victimisation rates are strikingly high. One possible explanation is that a relatively informal survey setting, in which responses are recorded on a mobile phone, can lead to different results to those recorded in a booklet of some 60 pages as used for the National Victims of Crime Survey. The data collection mode (e.g. Internet vs face-to-face) has been shown in other research to have an impact on victimisation survey results, but not anywhere near the extent suggested here.58

Another possible explanation for this anomaly may in fact be a result of Cosmo City's strong, albeit localised, social cohesion. Individuals receive information about the relative risk of victimisation 'not only through their direct experience with crime but also indirectly through others' experiences'.59 Social cohesion may facilitate the spread of information about crime experiences through the community, such that far more people hear about and to some extent have experience of a single crime incident. The familiarity with more crime incidents may well heighten a sense of crime victimisation risk, and it may have been this sense that filtered through into a question ostensibly about direct crime experiences. Put differently, although respondents were asked only about the crimes experienced by those in their own direct household, their sense of kinship may extend to many more people on their block or in their neighbourhood, so that the same crime is being reported by respondents in numerous, ostensibly discrete households.

This effect is not entirely unprecedented. A study on low-income communities in Latin America suggested that highly dense and strong social networks can allow the sense of crime victimisation risk to proliferate.60 Another study, on residents who were displaced following Hurricane Katrina, found that strong networks foster the transmission of rumours, raising the sense of crime risk.61 To the extent that Cosmo City's levels of social cohesion are high, it may be another example of such an effect. What is most interesting is that the heightened perceptions of risk - expressed, it is argued, as an exaggerated recollection of personal victimisation - are not matched by heightened levels of fear. More research to properly test the association is clearly required, but it may be that the same social cohesion that disperses the perception of crime victimisation risk also diffuses its emotional impact. High levels of social cohesion, whatever their independent impact on crime levels, may reduce fear of crime even as it raises perceptions of risk. These variables should certainly not be conflated. Policy may simultaneously succeed in promoting social cohesion and fail to address high crime levels, and it may thereby promote a sense of relative safety even while heightening crime level perceptions. Social cohesion is by no means a magic bullet for problems of and around crime.

Notes

1 Ray Forrest and Ade Kearns, Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood, Urban Studies, 38:12, 2001, 2125-43, 2125. [ Links ]

2 Pauline Cheong et al., Immigration, social cohesion and social capital: a critical review, Critical Social Policy, 27:1, 2007, 24-49, 25. [ Links ]

3 Joseph Chan, Ho-pong To and Elaine Chan, Reconsidering social cohesion: developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research, Social Indicators Research, 75:2, 2006, 273-302, 274. [ Links ]

4 Forrest and Kearns, Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood, 2125.

5 A Hirschfield and KJ Bowers, The effect of social cohesion on levels of recorded crime in disadvantaged areas, Urban Studies, 34:2, 1997, 1275-95, 1276. [ Links ]

6 Timothy Hartnagel, The perception and fear of crime: implications for neighborhood cohesion, social activity, and community affect, Social Forces, 58:1, 1979, 176-93, 177. [ Links ]

7 See e.g. Elaine Wedlock, Crime and cohesive communities, Report for the Home Office UK, 2006, 4. [ Links ]

8 Jonathan Jackson, Experience and expression: social and cultural significance in the fear of crime, British Journal of Criminology, 44:6, 2004, 946-66; [ Links ] Kristen Ferguson and Charles Mindel, Modeling fear of crime in Dallas neighborhoods: a test of social capital theory, Crime & Delinquency, 53:2, 2007, 322-49. [ Links ]

9 Fred Markowitz et al., Extending social disorganization theory: modeling the relationships between cohesion, disorder, and fear, Criminology, 39:2, 2001, 293-320, 294. [ Links ]

10 John Schweitzer, June Woo Kim and Juliette Mackin, The impact of the built environment on crime and fear of crime in urban neighborhoods, Journal of Urban Technology, 6:3, 1999, 59-73, 59. [ Links ]

11 Ana Pinto et al., Planning public spaces networks towards urban cohesion, Proceedings of the International Society of City and Regional Planners 46 Congress, 2010, 1-12. [ Links ]

12 Schweitzer, Kim and Mackin, The impact of the built environment on crime and fear of crime in urban neighborhoods.

13 Sarah Foster, Billie Giles-Corti and Matthew Knuiman, Neighbourhood design and fear of crime: a social-ecological examination of the correlates of residents' fear in new suburban housing developments, Heath and Place, 16:6, 2010, 1156-65, 1157. [ Links ]

14 Andrés Villarreal and Bráulio Silva, Social cohesion, criminal victimization and perceived risk of crime in Brazilian neighborhoods, Social Forces, 84:3, 2006, 1725-53, 1726. [ Links ]

15 Hartnagel, The perception and fear of crime, 178.

16 Dietlind Stolle, Stuart Soroka and Richard Johnston, When does diversity erode trust? Neighborhood diversity, interpersonal trust and the mediating effect of social interactions, Political Studies, 56:1, 2008, 57-75, 57. [ Links ]

17 Ibid., 59.

18 See e.g. Ichiro Kawachi, Bruce P Kennedy and Richard G Wilkinson, Crime: social disorganization and relative deprivation, Social Science and Medicine, 48:6, 1999, 719 -31. [ Links ]

19 Paul Bernard, Social cohesion: a dialectical critique of a quasi-concept, Report of the Strategic Research and Analysis Directorate, Department of Canadian Heritage, 2000, 2, http://www.omiss.ca/english/reference/pdf/pbernard.pdf (accessed 22 October 2015). [ Links ]

20 George Galster, Should policy makers strive for neighborhood social mix? An analysis of the Western European evidence base, Housing Studies, 22:4, 2007, 523-45. [ Links ]

21 Ivor Chipkin and Bongani Ngqulunga, Friends and family: social cohesion in South Africa, Journal of Southern African Studies, 34:1, 2008, 61-76. [ Links ]

22 George Okechukwu Onatu, Mixed-income housing development strategy: perspective on Cosmo City, Johannesburg, South Africa, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 3:3, 2010, 203-15, 207. [ Links ]

23 See e.g. UN Habitat, State of the world's cities 2012/2013: prosperity of cities, New York: Routledge, 2012, 69. [ Links ]

24 Onatu, Mixed-income housing development strategy, 210.

25 UN Habitat, State of the world's cities 2010/2011: bridging the urban divide, London: Earthscan, 2010, 89. [ Links ]

26 Allison Goebel, Sustainable urban development? Low-cost housing challenges in South Africa, Habitat International, 31:3-4, 2007, 291-302. [ Links ]

27 Christoph Haferburg, Townships of to-morrow? Cosmo City and inclusive visions for post-apartheid urban futures, Habitat International, 39, 2013, 261-68, 261-62. [ Links ]

28 Ibid., 261.

29 Karina Landman, A home close to opportunities in South Africa: top down vision or bottom up demand?, Town and Regional Planning, 56, 2010, 8-17, 10. [ Links ]

30 Federica Duca, New community in a new space: artificial, natural, created, contested. An idea from a golf estate in Johannesburg, Social Dynamics, 39, 2013, 191-209, 206. [ Links ]

31 Ivor Chipkin, Capitalism, city, apartheid in the twenty-first century, Social Dynamics, 39, 2013, 228-47, 229. [ Links ]

32 Dilip M Menon, Living together separately in South Africa, Social Dynamics, 39, 2013, 258-62, 259. [ Links ]

33 Chipkin, Capitalism, city, apartheid in the twenty-first century, 245.

34 Onatu, Mixed-income housing development strategy, 211.

35 Palmer Development Group, Urban LandMark land release assessment tool: Cosmo City case study report, 2011, 7, http://www.urbanlandmark.org/downloads/lram_cosmo_cs_2011.pdf (accessed 3 June 2015).

36 Brian Mulherron and Paddy Quinn, Basil Read Developers and Office of the City Manager (respectively), City of Johannesburg, personal communication, 5 May 2015.

37 Palmer Development Group, 6.

38 Mulherron and Quinn, 5 May 2015.

39 Marlene Wagner, A place under the sun for everyone: basis for planning through the analysis of formal and non-formal space practices in the housing area Cosmo City, Proceedings of the Southern African City Studies Conference, 2014, 7.

40 Haferburg, Townships of to-morrow?, 265.

41 Duka, New community in a new space; Chipkin, Capitalism, new city, apartheid in the twenty-first century; Menon, Living together separately in South Africa.

42 These comparisons for Johannesburg's ward 100, ward 97 and ward 113 from Wazimap, http://wazimap.co.za/ (accessed 12 February 2016).

43 Ibid.

44 Data obtained from the City of Johannesburg through personal correspondence.

45 Mulherron and Quinn, 5 May 2015.

46 Haferburg, Townships of to-morrow?, 267.

47 Statistics South Africa, http://census2011.co.za/ (accessed 10 February 2016).

48 As proposed, for example, in the South African context in Jarè Struwig et al., Towards a social cohesion barometer for South Africa, University of the Western Cape, Research Paper, 2011.

49 John Hipp and Andrew Perrin, Nested loyalties: local networks' effects on neighbourhood and community cohesion, Urban Studies, 43:13, 2006, 2503-24. [ Links ]

50 John Hipp, Block, tract, and levels of aggregation: neighborhood structure and crime and disorder as a case in point, American Sociological Review, 72:5, 2007, 659-80. [ Links ]

51 Haferburg, Townships of tomorrow?, 267.

52 Statistics South Africa, Victims of crime survey 2014/2015, Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2015, 10.

53 Ibid., 10.

54 Ibid., 12.

55 See e.g. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Global study on homicide, Vienna: UNODC, 2013, 9. [ Links ]

56 George D Gaskell, Daniel B Wright and Colm A O'Muircheartaigh, Telescoping of landmark events: implications for survey research, The Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 2000, 77-89; [ Links ] Jean Redpath, Using data to make a difference through victimisation surveys, SA Crime Quarterly, 32, 2010, 9-17, 10. [ Links ]

57 Penwell Dlamini and Shaun Smillie, Gauteng's crime central, The Times, 25 November 2014, http://www.timeslive.co.za/thetimes/2014/11/25/gauteng-s-crime-central (accessed 16 October 2015).

58 See e.g. Nathalie Guzy and Heinz Leitgob, Assessing mode effects in online and telephone victimization surveys, International Review of Victimology, 21, 2015, 101-31. [ Links ]

59 Villarreal and Silva, Social cohesion, criminal victimization and perceived risk of crime in Brazilian neighborhoods, 1726.

60 Ibid.

61 Shaun Thomas, Lies, damn lies, and rumors: an analysis of collective efficacy, rumors, and fear in the wake of Katrina, Sociological Spectrum, 27:6, 2007, 679-703. [ Links ]