Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Crime Quarterly

versión On-line ISSN 2413-3108

versión impresa ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. no.55 Pretoria mar. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/v0n55a49

RESEARCH ARTICLES

To be a somebody. Probing the roots of community in District Six

Don Pinnock

Investigative journalist and a Research Fellow at the Centre of Criminology and Safety and Violence Initiative (SaVI), University of Cape Town. As a criminologist, he was one of the co-drafters of the Youth Justice White Paper that became the Child Justice Act. don@pinnock.co.za

ABSTRACT

The term community is a moving target, widely used and often misused in defining a group of people in a particular area or with similar cultural practices. In Cape Town the sense of a loss of community is precisely what residents of an area known as District Six mourn, following their eviction and its destruction in the 1970s in terms of the racial Group Areas Act. What was it they perceived they had? And what did they lose, following their removal to the Cape Flats? In asking these questions it is possible to get a clearer understanding of the way in which multiple perceptions and relationships stitch together a social cohesiveness that undergirds the notion of community. And what happens when it is lost.

In the way that elephants gather in places where one of them once died, thoughtfully fondling the bones of the departed, I sometimes go to the empty fields of District Six and park, waiting for the full moon to rise. I always leave feeling melancholy. It is strange that, in such a rapidly expanding and infilling city such as Cape Town, this space has remained largely unoccupied for nearly half a century.1

There have been bureaucratic reasons for this, land claim delays and squabbles. But this hardly explains the city's sustained unwillingness or inability to re-people the area. Something else is at work here, the collective memory of an outrage done to a socially cohesive community, perhaps. Or maybe a sadness of what cannot come back to life or be regained for District Six's descendants, now scattered in the stark tenements and dangerous still-racial ghettoes of the Cape Flats?

Woven into the chaotic tapestry of the area seem to have been golden threads of community that, having unravelled, nobody seems willing to try to reweave lest their hearts be broken yet again by the impossibility. Where District Six once stood has, to a considerable degree, become holy ground, a treeless, windblown monument to lost community. What was this thing they called community?2

The history of a city is the story of its neighbourhoods. Each has a Zeitgeist, an identifiable personality. They all look and feel distinct from one another and have persistence over generations. Explaining Zeitgeist is difficult because it comprises many things: the type of buildings; the width of streets; the presence or absence of gates and walls; greenery or lack of it; street lighting at night; how people dress; who is hanging around; the friendliness, indifference or fear of people; the smell of cooking; rubbish or garden flowers; and the type of cars.

The most important undergirding of neighbourhood Zeitgeist is the degree of social efficacy.3 Organised communities have higher levels of formal and informal solidarity. There is consensus on important norms and values, often cohesion and social interaction among neighbours, formal and informal surveillance, and preparedness to intervene in altercations, question strangers and admonish children for unacceptable behaviour. These areas generally look and feel different. District Six was such an area and has come to represent a time when things were better. But what made it so? Is there something we can learn from it as we retro-fit fierce Cape Flats townships and build new ones?

The district was never easy to live in. It was overcrowded. Houses were often not repaired by absent landlords who were content to rack-rent to families by the room. Alleys often stank of urine and fish heads. But it is not the physical conditions that former residents yearn for, it is the way in which people interacted, a feeling of sharedness. In a city where this has been lost, it is this sense - these golden threads - that are most remembered and mourned.

District Six was built, over time, in waves and layers. It was originally farmland on the lower slopes of Table Mountain and first settled by Europeans attached to the Dutch East India Company. Then, in the early 19th century, it expanded rapidly when Cape Town's growing middle class began to build modest homes for themselves within easy reach of the central area. The wealthier merchants and officials already had houses closer to the city on land that their clerks and assistants could not afford. And so, on the outskirts of town, a middle-income community began to grow in District Six.4

The houses of these new residents were unpretentious, generally two-storied, and built as terraces in a style typical of the Cape under Victorian and Georgian rule. Narrow blocks were laid out parallel to the main artery, Hanover Street, and small, semi-detached houses with long service lanes were built. Later, in the 1880s, skilled European artisans -drawn to South Africa by the mining boom after the discovery of gold - began moving into Cape Town and settled in the district.

Following the outbreak of the South African War, Cape Town's population was swollen by an influx of troops as well as refugees from the Transvaal.5 Much building activity took place in District Six at this time and two- and three-storeyed blocks in a variety of architectural styles began to appear. Most of the properties in the area were owned by descendants of the European settlers, and a few by Asians.

No homes were provided specifically for workers in the city, however, and the limited houses available to them were filled to overcrowding, many being forced to squat on whatever land was available. After the war, a large number of businesses and offices were transferred back to the Transvaal. The houses in District Six were vacated (but not transferred out of European hands) as tradesmen, artisans and soldiers moved north. Through a filtering-down process, working-class families moved in and, by leap-frog movements, middle-income Europeans shifted out, first to Woodstock, then to Vredehoek, Observatory, Mowbray and beyond.6

Initially, the largely coloured working-class migration into the city had been circular, undertaken mainly by job seekers from surrounding farms and villages. As the transition from a farming economy to an industrial one gathered pace, it became a one-way flow of whole families. By the 1920s Cape Town's administrators were describing the march of the poor into Cape Town as 'formidable'.7 In 1936 the official census put the population of District Six at 22 440 and in 1946 at 28 377.8 Four years later the figure was around 40 000.9In 1950 the Housing Supervisor of the Cape Town Municipality told the Cape Times:

Almost every house in the district where the Coloured people live is packed tight. Children grow up and marry and in turn have children and are unable to find a place of their own. A family is turned out of an overcrowded house and finds a shelter with friends for a few days - which grow into weeks, months, years. They sleep in living-rooms, in kitchens, in passages, in garages, on stoeps; married couples share rooms with other married couples... Waiting-lists for accommodation grow longer and longer... Families wait anything from six months to 10 years before they can be re-housed.10

Many families in the area were extremely poor, living for generations by working at odd jobs here and there, scratching out an existence by forms of economic enterprise that counted profits in halfpennies and farthings. Viewing the district from their middle-class perspective, city officials and wealthier inner-city residents regarded the burgeoning area with alarm. There were warnings of disease and crime and these views, linked to apartheid laws, became the cornerstones for the later removal of people from the area. There was crime and some disease, but given the crowding, housing conditions and poverty, it was by today's standards extremely limited.11" This limitation of social harm was directly linked to the social cohesiveness and control exercised by extended families.

Throughout the migrations into Cape Town, it was always the extended family that formed the catch-net of the urban poor. Within it were people who could be trusted implicitly and would give assistance willingly, immediately and without counting the cost. In major calamities, such as the loss of a job or a death in the family, it was kinsfolk who rallied to support, and whose support lasted longest. Kin also helped find employment and accommodation and bribed or bailed you out of the clutches of the law. They were, in short, indispensable.12 In a hostile and uncaring world, extended families provided a refuge and a domain within which strategies of survival could be worked out.

Essential to the survival of the family, of course, were the wage packets brought into it. Like most unskilled earners in the third world, workers in District Six were paid an extremely low wage, which had to be conserved and stretched. The poor responded to this situation in typical fashion, organising systems of redistribution that helped extend meagre incomes to the limits of their elasticity. These patterns of redistribution percolated money through networks and finally into the pockets of those who were unable to obtain wage employment. It was, above all, a social form of redistribution, operating among friends, neighbours, workmates, acquaintances and friends of friends.13 The fine-grained lattice of community enterprise was noted by journalist Brian Barrow:

The place has more barbershops to the acre than anywhere else in Africa. There are tailors by the score, herbalists, butchers, grocers, tattoo-artists, cinemas, bars, hotels, a public bath-house, rows of quaint little houses with names like 'Buzz Off' and 'Wy Wurry' and there is a magnificent range of spice smells from the curry shops. The vitality and variety in the place seem endless and the good-humour of the people inexhaustible. Anything could happen and everyone in the end would laugh about it.

Go into one of the fruit and vegetable shops and you soon realize how the very poor manage to live. In these shops people can still buy something useful for 1d. They can buy one potato if that is all they can afford at the moment, or one cigarette. You can hear them ask for an olap patiselli (a penny's worth of parsley), a tikkie tamaties or a tikkie swart bekkies (black-eyed beans), a sixpence soup-greens, an olap knofelok (garlic) or olap broos, which means a penny's worth of bruised fruit.14

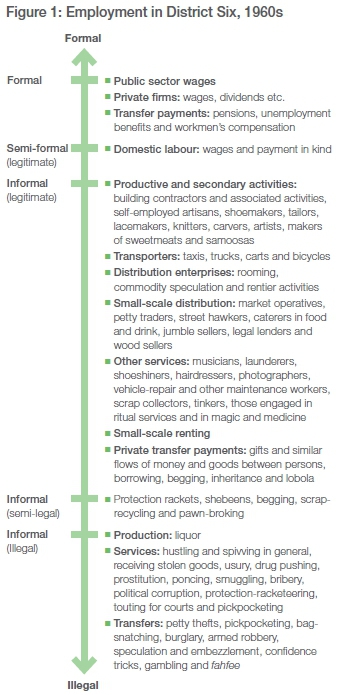

An inventory of employment in District Six in the early 1960s gives a sense of the underlying fabric that kept it alive.15

In all this, the extended family was the ground floor of small-scale economic activities. In 1937 a Commission of Inquiry found that 'the entire Cape Coloured family in the urban areas very often forms the earning-unit, the income of the parents and one or more of the children being pooled to meet household needs'.16 The area became known for the ingenuity, novelty and enterprise of its residents. By day it hummed with trade, barter and manufacture, and by night it offered the 'various pleasures of conviviality or forgetfulness'.17

The district's networks of kin, worship, friendships, work and play involved an intricate mix of rights and obligations, intimacies and distances, which grounded a sense of solidarity, local loyalties and traditions. The former warden of the Cape Flats Distress Association, Dr Oscar Wollheim, lyrically described the intricacy of these social webs:

Each individual has his own personal web which varies in size and complexity, according to the impact he makes on those around him and the influence he wields in the community. His usefulness to and within the community is determined entirely by the freedom with which he is able to move in and about his web, his knowledge of its structure and the facility with which he is able to make contact with the correct position of the web at the correct time.

The rings closest to the centre are represented by the man's immediate and extended family and his closest friends. The next would represent his acquaintances, his church, his school and the clubs he frequents. Other rings represent his employer, his transport and communications, the shops he frequents, the municipal and other officials he meets, his doctor, the police, the postman, the tax official. The anchors of the web represent the customs, habits and moral concepts of the community in which he lives.18

Maintaining order

The area's rich social fabric had an unintended function as well. Not only did it provide the possibilities of a roof and an income, it also fostered networks of social control. On the district's many shallow verandas grandparents commented, gossiped and watched. Because effective police protection was lacking, this surveillance was beneficial, even essential, to life. It kept things 'safe'. The interconnectedness and effect of this surveillance was described to John Western by a former resident of the organisationally similar suburb of Mowbray:

When I was 15 or 16 if we did anything rude, offhanded, in the street - like going to bars or smoking or taking a dame out - you'd get a pak [hiding] at night at home; they [parents] knew about it right away... It was the old men who used to stand at the corners chatting or sit on the stoeps; they'd pretend to be reading the Koran or a comic or playing karem or whatever, but out of the corner of their eye they were really watching you.19

This surveillance provided safe spaces for children to be children, as Brian Barrow observed:

Children everywhere. Shouting, laughing, whistling, teasing, darting between old men's legs, running between fast-moving buses and cars and missing them by inches with perfect judgement. Poor, underfed children but cheeky, confident, happy and so emotionally secure in the bosom of their sordid surroundings. Everyone loved them. To them, it seemed, every adult on those busy streets was another mother, another father.20

Powerful families also 'ordered' the district through their connections, inter-marriages, agreements, 'respect' and, in some cases, their access to violence. An aspect of this type of control was the rise of the Globe Gang.

In Cape Town today, gangs are synonymous with urban decay - social structures that dissolve the glue of community. But what is generally missed in this representation is that they are at the same time the outcome of social ordering within the environment in which they exist.21 In contexts of crowding, joblessness and low income (if any at all), they are a response by young people attempting to make sense of their space within the neighbourhood. Within certain contexts - where informal surveillance is in place, backed by strong community disapproval of behaviour beyond certain limits - gangs can have the same function as sport or cultural activities, where adolescent approval can be won. When social controls weaken or are absent, gang activity generally becomes predatory, destructive to both its members and the community. The Globe Gang is an example of this transition.

During World War Two, street corners in the district seemed to fill up overnight and the sight of people or even whole families sleeping on staircase landings and in doorways became common. Pressure began to build up over territory for hawking, shebeening, prostitution or just for standing space. Youths from the 'outside' began hanging together, with empty stomachs and nothing much to do. They started hustling, picking up this and that from shops, leaning on a few people for cash or favours and living by shifts and ruses of all kinds. Police methods of dealing with these groups were simple, direct and ineffective: 'We would pick them up and fine them and they could be hired out for some work while under sentence, usually to farms,' a former policeman explained. 'These kinds of people were just idle loiterers who took part in illegal activities now and then.'22

The way members of the district's community responded was equally direct. Sons from the 'old' organised families, consisting mainly of shopkeepers, skilled craftsmen and better-off hawkers, used to congregate under a streetlight alongside the Globe Furnishing Company in Hanover Street opposite the Star Bioscope, watching the abundant street life of the district. They were aware that the security of their parents was being threatened and resolved to take action.

In the early 1940s a group of scruffy youths would stand at the door of the Star, extracting a penny 'tax' from every patron. One night the Globe group, mostly Asians from the Muir Street area, decided they had had enough. They gathered together their fathers' workers and barrow boys, armed them with sticks and implements from a nearby stable, and thrashed the cinema skollies.

Among the Globe members were bricklayers, hawkers and painters. Its chief, Mikey Ismail, was a plasterer. At its centre was the Ismail family, one of whom, A Ismail, was a city councillor. Several of his brothers controlled the district's morning vegetable market, one ran a bus service and four had general dealer shops. 'The Globe were not criminals,' according to a tailor who made their clothes. 'They started to control the Jesters of Constitution Street, who were beginning to maak soos hulle wil [do what they like]. Their aim was to eventually break all gangs, to clean up the district.' A member of the Globe gang told me:

The Globe hated the skollie element that started coming into the district, like the people who robbed the crowds on celebrations or when there were those marches in town with the Torch Commando or Cissy Gool's singsong [demonstration] outside Parliament buildings. Mikey and the boys would really bomb out the skollie element when they robbed the people then. They tore them to ribbons.23

The Globe was, essentially, an organised vigilante extension of an extended family network. According to a close associate of the Globe at the time, Vincent Kolbe:

The Globe ... respected each other and their families and so on. There were only a few who smoked pot and really got gesuip [drunk], but never the top dogs. They always tried to do things that wouldn't bring a scratch to their good family name. You know all these people I'm talking about are wealthy businessmen today - except, of course, Mikey is dead now. The Globe were the most decent and well-bred guys ever. All their parents were well-to-do businessmen with flashy cars and good clothes. The leaders were always beautifully dressed. Mikey had silk shirts specially made for him. And he drove around in lovely cars. And the women! Mikey always had the best women around him.24

So it may have remained, but in 1966 District Six was declared a whites-only area. This was met, initially, by disbelief, then anger and finally acceptance. The fabric of community began unravelling. It is difficult to make a direct link between the actions of the Globe and the mood of the time, but from about that period the gang turned bad. It collected 'protection' money from shopkeepers, clubs and cinemas, ran extortion rackets and controlled blackmail, illicit buying of every kind, smuggling, shebeens, gambling and political movements in the district. Then its leader, Mikey, was killed - stabbed with a kitchen knife by the brother of a girl who thought he was molesting her. Mikey's brother was jailed for blackmail. As the gang's rackets increased, it also lost the support of the class that had given birth to it. Gradually prison elements infiltrated the Globe. Vincent Kolbe describes the process:

Slowly there came the skollie element. A guy from Porter Reformatory joined them: Chicken. Then prisoners from up-country who'd never been in the cities. They raped and had tattoos on their faces and necks and killed anybody, for nothing. Young boys arrived, and carried guns for no reason. As the community became more divided over the removals and extended families began breaking up, more gangs were formed, like the Bun Boys, the Stalag 17, the Doolans, the Mongrels, the Born Frees. These types were really just snot-nosed young boys. Then one day somebody interfered with a gang in the District and this gang thought it was the Globe but it wasn't. They attacked us and this set off the most terrible war. People were killed and the Globe decided to bust every gang everywhere. They couldn't stop. And that was the start of the Globe's really bad name.25

Time of the bulldozers

For District Six, throughout the 1950s, storm clouds were gathering. The National Party won the elections in 1948 on a segregationist ticket and began to promulgate racist laws. The aim of the Group Areas Act of 1950 was 'to provide for the establishment of group areas, for the control of the acquisition of immovable property and the occupation of land and premises'.26

For a while, however, official 'labour preference' for people designated 'coloured' over those described as 'Bantu' ensured temporary protection from the winds of change. Fierce resistance to the act,27 plus the National Party's slim majority in Parliament, held off its roll-out for nearly 15 years, but eventually, in 1966, the sword fell. This was signalled by a Cape Town City Council committee meeting called in that year to discuss the 'proclamation of District Six under the Group Areas Act as an area for ownership and occupation by members of the White group'.28 Government officials gave their reasons for the removals:

• Inter-racial interaction bred conflict, necessitating the separation of the races

• The area was a slum, fit only for clearance, not rehabilitation

• The area was crime-ridden and dangerous

• It was a vice den of gambling, drinking, and prostitution

Removal of around 2 000 families and the destruction of houses began in 1968.

The Group Areas Act was to undermine and ultimately smash social cohesion in District Six and many other areas. In ploughing up networks of knowledge, relationships, shared experiences and history, the scaffolding of a culture was systematically dismantled. The effects of racial legislation were, as Oscar Wollheim explained,

[l]ike a man with a stick breaking spiderwebs in a forest. The spider may survive the fall, but he can't survive without his web. When he comes to build it again he finds the anchors are gone, the people are all over and the fabric of generations is lost. Before, there was always something that kept the community ticking over and operating correctly ... there was the extended family; the granny and grandpa were at home, doing the household chores and looking after the kids.

Now, the family is taken out of this environment where everything is safe and known. It is put in a matchbox in a strange place. All social norms have suddenly been abolished. Before, the children who got up to mischief in the streets were reprimanded by neighbours. Now there's nobody, and they join gangs because that's the only way to find friends.29

In 1974 the Theron Commission was to conclude that 'no other statutory measure had evoked so much bitterness, mistrust and hostility on the part of the Coloured people as the Group Areas Act'.30This statement echoed Wollheim, who had warned in 1960 that 'we can look forward to a period of increasing social dislocation, which will have its root in no other causes but in the application of the [Group Areas] Act'.31

Counting the costs

One of the greatest complaints I heard about Group Areas removals while doing research for a book on relocations was that individual people or singular families, rather than whole neighbourhoods, were moved to the Cape Flats.32 Extended families were not considered and only nuclear family dwellings were provided. Informal childcare and surveillance evaporated. The stresses resulting from these changes brought with them psychological difficulties and skewed 'coping' behaviour. Marital relationships were upset and the rates of divorce and desertion rose. Parent-child relationships also became problematic - often because of the father's sense of inadequacy in his new environment. For young people there was nowhere to go but out on the street.33

The destruction of District Six also blew out the candle of household production, craft industries and services. The result on the Cape Flats was a gradual polarisation of the labour force into those with more specialised, skilled or better paid jobs, those with the dead-end, low-paid jobs, and the unemployed. As the new housing pattern dissolved kinship networks, the isolated family could no longer call on the resources of the extended family or the neighbourhood. The nuclear family itself became the sole focus of solidarity.

This meant that problems tended to be bottled up within the immediate interpersonal context that produced them. At the same time, family relationships gathered a new intensity to compensate for the diversity of relationships previously generated through neighbours and wider kinship ties. Pressures gradually built up, which many newly nuclear families were unable to deal with. The working-class household was thus not only isolated from the outside, but also undermined from within.

These pressures weighed heavily on house-bound mothers. Neighbours were not well known and, with nobody to supervise them, the street was no longer a safe place for children to play. The only space that felt safe was a small flat. One route out of the claustrophobic tensions of family life was the use of alcohol and drugs. This became the standard path of many men. Children were shaken loose in different ways. One way was into early sexual relationships and perhaps marriage. Another was into fierce streetcorner drug-driven subcultures, reinforcing the neighbourhood climate of fear.34 The situation was to be compounded by rising unemployment among young people.

To assess the effect of Group Areas removals on families, I made a comparison between family life and working-class culture in an 'inner city' working-class area and on the Cape Flats, where many people had been relocated. The established area was Harfield Village, which forms part of Claremont (it was later gentrified and is now predominantly white).35

At the time of the survey, Harfield Village was a suburb 'in transition' from a mixed to a white Group Area, and only about a hundred original families remained. On average, families had resided there for 19 years, although more than 10% had been there 50 years or longer. The average number of people in each house was a fraction above five.

What was significant about the area was the high number of people available for what might be described as 'crisis support'. Some 80% of the people interviewed had relations in Harfield and slightly more than this had close friends in the area. This was despite the fact that 65% had seen related families moved from the village by Group Areas. There was no crèche in Harfield. Of those mothers whom I interviewed, the majority looked after their own children and a sizable number relied on relations to do this.

In total, 95% of children aged under 16 were taken care of within extended families, the remaining number being minded by friends. In comparison with the Cape Flats this was an extremely high level of family-based childcare. Harfield had all the benchmarks of a stable supportive community. This was also the case in Mowbray, where John Western found an average residency of 33 years and where 70% of his interviewees were related to at least one other physically separate household.36

The Cape Flats survey focused specifically on mothers living in 35 different housing estates. The average number of people in each dwelling was a little over seven and the average length of residency was a mere four years. Of the sample, 44% of the Cape Flats mothers were working and 25% were raising a family without a husband.

In order to gauge changes in living patterns, the mothers were asked about their own childhoods and then about their children. The findings showed a marked historical fall-off in access to family networks of childcare. A high percentage of children under 16 received no parental care during the day, while a very small number were placed in crèches. When asked about any problems they were experiencing, the greater number of mothers said it was a fear of gangs and lack of police protection.37

Crime fills the vacuum

The failure of the current government to reduce poverty or to prevent rapid squatter settlements, compounded by older racial ghettoisation and the division of the city between glitter and ghetto, has - by design, inability or perceived necessity -resulted in massive social disorganisation of poorer neighbourhoods. Despite the turnover of residents through time, these conditions persist and residents in 'those kinds of places' continue to be seen as 'those kind of people'.38 They are labelled and treated accordingly to a point where many of them embody the definition and act accordingly, lashing out or wearing their situation as a badge of ironic resignation. In these neighbourhoods, collective efficacy declines, violence increases and other forces move into the power vacuum in an attempt to control, stabilise, disrupt or benefit.

The impact of social disconnectness was sketched by American criminologist Robert Sampson in his work on Chicago's high-risk areas:

Neighborhood characteristics such as family disorganisation, residential mobility and structural density weaken informal social control networks. Informal social controls are impeded by weak local social bonds, lowered community attachment, anonymity and reduced capacity for surveillance and guardianship. Residents in areas characterised by family disorganisation, mobility and building density are less able to perform guardianship activities, less likely to report general deviance to authorities, to intervene in public disturbances and to assume responsibility for supervision of youth activities. The result is that deviance is tolerated and public norms of social control are not effective.39

Contact crime across a city tends to cluster in such neighbourhoods, as do low income, high unemployment and raised levels of interpersonal conflict and stress.40 What is important to note, however, is that social disorganisation is a property of neighbourhoods, not individuals, and that crime is one of its characteristics. The difference between District Six and newer neighbourhoods such as Manenberg and Lavender Hill, or the more recently developed Khayelitsha, is that the former was a community that ordered and policed itself and the latter are, comparatively, socially disarrayed and organisationally unglued. Poverty is not merely deprivation, it is isolation and social confusedness.

As a consequence, many of the residents in Cape Town's high-risk, low-income townships voice a degree of fatalism about transformation in their own lifetime and a moral cynicism about crime, which they view as inevitable. As a result, contact crimes are not vigorously condemned, because of an inability to prevent them occurring. Given the lack of assured conventional economic advancement, many residents shrug at an income based on the theft of vehicles or sale of drugs and may even benefit from or depend on it themselves.

In 1994 the newly elected African National Congress (ANC) government was to inherit a Cape Town working class that was like a routed, scattered army, dotted in confusion about the land of their birth. In the lonely crowd of satellite clusters with rising rates of violence, the townships had become increasingly difficult places to meet people after work, favouring silent conformity and not rebellion.

The ultimate losers were the working-class families. The emotional brutality dealt out to them in the name of rational urban planning has been incalculable. The only defence the youths had was to build something coherent out of the one thing they had left - each other. Between windblown tenements on the dusty sand, gangs blossomed. The city's urban managers now had a major problem on their hands - violent crime.

Searching for themselves

As I watch the full moon slowly illuminate grassy mounds covering the bricks and mortar of buildings that once housed District Six, the saddest thing is the silence. Here once was a community that buzzed with life and laughter. What former residents miss and yearn for is, I think, not so much where they once lived, but who they once were, living there.

What, then, can we say about the golden threads that illuminated the tapestry of this particular urban neighbourhood? People may be defined by their built environment - be it patched and crumbling - and the economy that supports it, even if in halfpennies and farthings. But these are pale threads. More robust and colourful are yarns of context - of others, mainly extended family, within whose regard a person is held. Lacing through the warp and woof of that regard run bright strands of what a community really is: the sense that, without doubt, you are somebody in a place where people accord you respect.

Exposed to the harsh acid rain of racist urban management that dissolved communities in Cape Town and unpicked the fabric of their lives, this gold turned to tinsel. In the social tangle amid unforgiving tenements on the dusty Cape Flats the message was clear: 'You're nobody.' Two quotes capture the essence of what had been and what became. The first is Brian Barrow again:

District Six would be nothing without its people and way of life. Above all it was one of the world's great meeting places of people of many races, religions and colours and it proved that none of these things really matters. It had a fundamental honesty in that no man or woman who lived there tried to be anything but what they were. And this perhaps was the real secret of the happiness of District Six.

There was no bluff and everyone knew where he stood, knew what was attainable and whatwas not. At times it was a place of violence. But mostly it was a place of love, tolerance and kindness, a place of poverty and often degradation, but a place where people had the intelligence to take what life gave them and give it meaning.41

The second quote is from the 19th century French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville, speaking of the isolation that can result from planned urban reconstruction:

The first thing that strikes one's observation is an uncountable number of men. Each of them living apart is a stranger to the fate of all the rest - his children and his private friends constitute to him the whole of mankind; as for the rest of his fellow citizens, he is close to them, but he sees them not; he touches them, but he feels them not; he exists but in himself and for himself alone; and if his kindred still remain to him, he may be said at any rate to have lost his country.42

What the residents of District Six had was a community that was socially cohesive and held together by friendships and obligations within and between extended families. What they lost after laws and bulldozers scattered them across the Cape Flats was a sense of who they are. That is one of apartheid's most insidious crimes.43

Notes

1 In February 1966 the government of South Africa proclaimed the area abutting the city's central business district as being for the exclusive use of white people. Those who were not - people defined as coloured, Indian or African - were removed, but those for whom it was proclaimed never moved in.

2 Most of the historical research for this article was done for my MA thesis (Don Pinnock, The brotherhoods: street gangs and state control in Cape Town, University of Cape Town [UCT], 1982), [ Links ] which became a book (Don Pinnock, The brotherhoods, Cape Town: David Philip, 1984). [ Links ] As little research had been done on gangs in the city, most of the information came from interviews, participant observation, official city and state documents and newspaper reports. More contemporary research and analysis is from my book Gang town (Don Pinnock, Gang town, Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2016). [ Links ]

3 Social efficacy is the extent or strength of a community's belief in its ability to complete tasks and reach goals. See Robert Sampson, Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012. [ Links ]

4 John Western, Outcast Cape Town, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. [ Links ]

5 Transvaal was the name of one of the provinces until borders were redrawn and provinces renamed in 1994.

6 Western, Outcast Cape Town.

7 Pinnock, The brotherhoods.

8 These figures were given by Dr Oscar Wollheim of the Cape Flats Distress Association (CAFDA). Further data can be found in Office of Population Research, The 1936 census of the Union of South Africa, Population Index, 9:3, July 1943, 153-155.

9 AJ Christopher, The Union of South Africa censuses 1911-1960: an incomplete record, Historia, 56:2, November 2011. [ Links ]

10 Cape Times, 20 June 1950 (copies available in the South African Archives, Cape Town).

11 Interview with Sergeant Willem Nel, former head of the Police Special Squad, District Six, Cape Town, 1981.

12 D Webster, The social organization of poverty, African Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Seminar Paper, 1980, 15. [ Links ]

13 Ibid., 16.

14 Brian Barrow, Behind the dark doors of District Six, Wollheim Collection, UCT, 1966. [ Links ]

15 This information is from extensive interviews with former District Six residents and a survey of the Cape Times and Cape Argus of the decade.

16 Union of South Africa Parliament, Report of the Cape Coloured Commission, U.G. 54-1937.

17 Brian Barrow, who wrote the text for the photographic book by Cloete Breytenbach, The spirit of District Six, Cape Town: Struik, 1970. [ Links ]

18 OD Wollheim, Peninsula's tragedy of the poor, Cape Times, 26 January 1959.

19 Western, Outcast Cape Town, 312.

20 Barrow, The spirit of District Six.

21 For a more detailed discussion of this seeming paradox, see Pinnock, Gang town.

22 Interview with Sergeant Willem Nel, former head of the Police Special Squad, District Six, Cape Town 1981. All interviews and supporting materials are in the Don Pinnock Collection, Mayibuye Centre, University of the Western Cape.

23 Interview with 'Gums', a Globe gang member, Hanover Park, Cape Town, 1980.

24 Interview with Vincent Kolbe, Wynberg, 1981.

25 Ibid.

26 South African Group Areas Act (Act 41 of 1950), Pretoria: Government Printer, 1950.

27 Resistance came in the form of rolling action against apartheid from the ANC's Programme of Action in 1949, the Defiance Campaign of 1952, the anti-pass campaigns of the Federation of South African Women from 1954, the Congress of the People and the creation of the Freedom Charter in 1955 and the formation of the SA Congress of Trade Unions the same year. What followed was the massive Treason Trial in 1956, the Sharpeville massacre and the state of emergency declared afterwards, the Rivonia Trial, which jailed Nelson Mandela and others, and the ANC's turn to sabotage from 1964.

28 Special and adjourned ordinary meeting agenda, Cape Town City Council, 1 March 1966, South African Archives, Cape Town.

29 Interview with Dr OD Wollheim, Cape Town, March 1981.

30 Republic of South Africa Parliament, Commission of inquiry into matters relating to the coloured population, R.P. 38-1976 (Theron Commission), 261, 227.

31 OD Wollheim, Group areas in South Africa, Wollheim Collection, UCT, undated article. [ Links ]

32 Pinnock, The brotherhoods.

33 This information comes from extensive interviews conducted by the author on the Cape Flats in 1980/81.

34 Pinnock, The brotherhoods.

35 The survey was conducted by the author with 15 mothers each in Harfield Village, Lower Claremont, Hanover Park and Manenberg in 1982. The results were not published but were used to underpin the chapter Unemployment and the breaking of the web, in Pinnock, The brotherhoods.

36 Western, Outcast Cape Town, 312.

37 Pinnock, The brotherhoods.

38 This depiction is from R Stark, Deviant places: a theory of the ecology of crime, Criminology, 25, 1987, 893. [ Links ]

39 RJ Sampson, Communities and crime, in MR Gottfredson and T Hirschi (eds), Positive criminology, Newbury Park: Sage, 1987, 109. [ Links ]

40 See Charis Kubrin, Social disorganization theory: then, now and in the future, in Marvin Krohn, Alan Lizotte and Gina Penly Hall (eds), Handbook on crime and deviance, New York: Springer, 2009. [ Links ]

41 Breytenbach, The spirit of District Six, 6.

42 Alexis de Tocqueville, What sort of despotism democratic nations have to fear?, in Democracy in America, vol. 1 and 2, 1835 and 1840. [ Links ]

43 Parts of this narrative are drawn from Pinnock, Gang town.