Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SA Crime Quarterly

versão On-line ISSN 2413-3108

versão impressa ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. no.54 Pretoria Dez. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sacq.v54i1.2

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A 'best buy' for violence prevention: Evaluating parenting skills programmes

Inge Wessel; Catherine L Ward

Department of Psychology at the University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Effective parenting programmes are central to successful violence prevention efforts. Although parenting programmes are available in South Africa, few are evidence-based. This lack of evaluation makes it impossible to know whether programmes are helpful or harmful and whether they use resources efficiently. This article outlines a process for gauging the extent to which parenting programmes incorporate evidence-based practices, which may then assist in identifying promising programmes. This involves the application of two interlinked instruments - an interview schedule and rating metric. It was applied to 21 group-based parenting programmes in South Africa that were identified via convenience and snowball sampling. Results indicated that the use of evidence-based practices was low, especially in terms of monitoring and evaluation. Findings highlight clear areas where programme strengthening is needed. A similar process could be used to identify other promising violence prevention interventions.

Levels of violence in South Africa are extremely high,1 and the consequences are far-reaching. Not only does violence negatively affect health and wellbeing, it also places great strain on the health, welfare and criminal justice systems, and hinders social and economic development.2 Effective violence prevention interventions are urgently needed. While there are violence prevention programmes in South Africa, few have been through a rigorous evaluation to determine their effectiveness.3 This lack of evaluation is concerning because no country, least of all a relatively low-resource one such as South Africa, can afford to roll out what might be ineffective programmes, thus wasting resources that could be put to better use. Additionally, until a programme is evaluated, one cannot determine whether it is helping or harming beneficiaries.

Because so few programmes have been evaluated, one approach may be to first identify practices common to effective evidence-based programmes and then investigate to what extent local programmes incorporate them.4 The more evidence-based practices are included in a programme, the more likely it is to achieve positive outcomes.5 This approach offers a relatively quick and easy way for decision-makers to select interventions to consider for evaluation and wider roll-out.

This article outlines how an understanding of the state of parenting programmes in South Africa was gained through investigating the use of evidence-based practices, a process that could certainly be applied to other types of prevention programming with minimal adjustment. Parenting programmes were selected for this research as they are central to violence prevention, with the World Health Organization recently identifying programmes that enable a healthy parent-child relationship as a 'best buy' for violence prevention.6 Parenting programmes enable parents to learn strategies to strengthen their relationships with their children and also to manage misbehaviour without the use of harsh discipline, and so can help to reduce both child maltreatment (itself a form of violence) and youth violence.

In South Africa, the need for these programmes has been recognised in Chapter 8 of the Children's Act, which states that the government must provide and fund prevention and early intervention programmes to prevent child maltreatment.7 It also recognises that programmes that develop parenting skills are critical to promoting children's wellbeing. The Western Cape provincial government has acknowledged the potential role of parenting programmes in preventing violence by including them in its Integrated Provincial Violence Prevention Policy Framework.8

This article will firstly provide an overview of evidence-based practices within the context of parenting programmes. Secondly, it will outline the development of instruments used to gain information from programmes and to rank programmes. Thirdly, it will discuss the findings from the application of these instruments to parenting programmes in South Africa. Finally, it will make some comments about the use and adaptation of this process for other areas of violence prevention.

Evidence-based practices for parenting programmes

Programme targeting

Needs assessment

Programmes are more likely to be effective if they are informed by a clear understanding of the nature, prevalence and distribution of the targeted problem.9This understanding should be gained via a formal needs assessment, which is ideally conducted when the idea for the programme is conceptualised. A needs assessment reveals whether services are needed, what services are currently available, and which intervention type would be most suitable and acceptable for the target population. This information then guides programme development and implementation.10

Programme timing

Programmes are best implemented at a time in a child's life when they will have the greatest impact, and when parents will be most receptive to change.11Additionally, programmes must be developmentally appropriate, in terms of both the targeted age-range of children and the cognitive, social and intellectual abilities of parents.12

Recruitment and retention

Parenting programmes are more likely to recruit appropriate parents if they have explicit screening processes in place. Screening allows programme staff to establish if individuals meet the criteria for the programme. It also enables staff to refer parents on if they require services that are beyond the scope of the programme, thus maximising the chances that those receiving the programme will in fact be helped, and that the resources ploughed into the programme are used to maximum effect.

Retention is another issue that needs careful thought. Many parents, especially those in greatest need of intervention, do not access services, or drop out of them. For example, recorded drop-out rates for family-centred interventions for parents of children at risk of conduct problems have been as high as 50%.13 Not only does this retention failure waste resources and potentially lead to low morale of group leaders, it also means that many parents who could benefit from programmes are missing out completely or are only receiving bits of the intervention (which may not be as effective as the whole programme).

It is therefore essential to carefully consider appropriate recruitment and retention techniques and address barriers to programme access and participation, so that parents who might otherwise And it difficult to engage in parenting programmes, are more likely to do so.14 This may involve delivering programmes at times convenient to parents, delivering programmes at venues that are easily accessible to parents, providing child care, and ensuring that programme content is culturally appropriate and relevant to parents.

Programme design and delivery

Programme theory

Many programmes are based on intuition, available resources and past experiences, rather than on solid evidence.15 However, programmes are more likely to be effective if they have a strong theoretical basis and clearly articulate the mechanisms by which they aim to achieve their goals.16 If a programme theory is not plausible in terms of the scientific literature, that programme is unlikely to be effective, however well it is implemented.

Programme content

Although specific programme content will vary, depending on desired outcomes, certain content components have been identified as consistently having a positive impact on parenting and child outcomes. For programmes targeting parents of children aged 0 to 7, for instance, these include increasing positive parent-child interactions and emotional communication skills, as well as teaching parents to use time out, and emphasising the importance of parenting consistency.17

Programme delivery

Parenting programmes are also more likely to foster lasting positive outcomes if they aim to change parents' attitudes, behaviours and goals, rather than to simply improve their knowledge.18 Programmes should take a collaborative and strengths-based approach, rather than one that is didactic, expert-driven and deficit-based.19 Additionally, it is key that there is an active skills-based component that provides parents with an opportunity to role-play new skills in a safe and supportive environment.20

Programme content should be clearly outlined in programme materials to increase the likelihood of the programme being delivered as intended.21However, it is important to remember that even if this is done, intervention drift may still occur during implementation. For instance, content that appears within the materials may be inadequately addressed during sessions, or aligned activities, such as role-plays, may receive an insufficient time allocation or may be omitted by facilitators. This reflects the necessity of adequately training and supervising facilitators, as well as conducting process monitoring to ensure that the programme is delivered with fidelity.

Programme dosage

Programmes are more likely to generate desired outcomes if they provide participants with a sufficient amount of intervention.22 The necessary 'dosage' will depend on the target population's level of risk.23For example, longer programmes tend to be more effective than shorter programmes in addressing severe problems and high-risk parents.24 On the other hand, recent studies have found that brief interventions may be effective for universal roll-out for parents facing less severe problems. For instance, Mejia and colleagues recently found that a group-based, single session version of the evidence-based parenting programme, Triple P, led to reductions in parent self-reports of child behaviour problems.25 This positive effect was maintained over time and was even more significant at the six-month follow-up assessment.

Whatever the duration of a programme, the inclusion of booster sessions after programme completion may assist parents in maintaining positive programme outcomes.26

Training and supervision

Most evidence-based parenting programmes in high-income countries use professionals, including nurses, psychologists or social workers, to deliver interventions.27 There is some evidence (at least from one home-visiting programme for infants) that professionals may be more effective than para-professionals.28 However, there is also evidence that positive outcomes can be achieved when using para-professionals, including community-based facilitators. For example, the results of a randomised controlled trial of a peer-led parenting programme delivered in a socially deprived part of inner London compared favourably with professional-led programmes in terms of improved parenting and reductions in child behaviour problems.29 The peer-led intervention also had a low dropout rate, which may indicate that this approach is an acceptable means of supporting parents.

The decision whether to use professionals or para-professionals as facilitators should be informed by an understanding of various factors, including how effective each has shown to be with the target population, training and supervision needs, turnover rates and cost,30 and how the programme was designed and trialled. This being said, the use of para-professionals may be necessary for a country such as South Africa where it is unlikely that there are sufficient numbers of professionals to deliver programmes on a large scale.

Whether professionals or para-professionals are used, training is critical to programme fidelity and effectiveness.31 Since parenting programmes are transformative in nature, it is necessary that supervisors and facilitators go through the programme as participants during the training process.32 Training should also include information on the programme's theory, strategies to increase participant engagement, facilitation skills, as well as content on ethics, confidentiality and handling sensitive situations.33 In order to increase the likelihood of evaluation uptake, the importance of monitoring and evaluation should be discussed and the steps to collect necessary data should be explained.34

Together with high-quality pre-service and in-service training, ongoing and regular support and supervision provide the foundation for an effective programme.35 The importance of support and supervision was demonstrated in the Birmingham (UK) Brighter Start initiative, which included the evaluation of the Incredible Years BASIC parenting programme and the Level 4 Group Triple P parenting programme.36 The former led to improvements in both parent and child outcomes, while the latter showed no effects. Poor implementation was identified by the evaluators as a possible reason for the lack of effects shown by Triple P, a programme that does not include mandatory facilitator supervision (unlike Incredible Years). Supervision is key to ensuring that programmes are implemented as planned.

Monitoring and evaluation

Programmes are strengthened by the inclusion of well-designed monitoring and evaluation processes throughout their duration.37 Monitoring systems assist with understanding programme reach, programme fidelity, relevance to participants and whether the programme needs any adaptations.38Outcome evaluation is particularly essential as it generates information on intervention effectiveness. Together, monitoring and evaluation data can be used to justify ongoing investment and inform further programme development.

The randomised controlled trial is typically considered to be the gold standard for outcome evaluation as it allows for the strongest conclusions to be drawn regarding a programme's effect.39However, if this design is not feasible, other high-quality evaluation designs are available and may achieve the same goal.40

Since outcome evaluations are resource-intensive, it is helpful to conduct two steps prior to initiating an evaluation. The first step is to conduct an assessment to determine whether carrying out an evaluation would be feasible and likely to generate useful information.41 Typically, a programme is likely to be evaluable if it:

- Has a plausible programme theory

- Serves the intended target population

- Has a clear and specified curriculum

- Implements activities as planned

- Has realistic and attainable goals

- Has the resources outlined in the programme design

- Has the capacity to provide the necessary data for an evaluation42

The second step is to conduct a pilot evaluation to determine whether or not the programme is promising and warrants a larger scale evaluation in its current form.43

Programme scalability

Unless evidence-based programmes are scaled up successfully and widely used, their impact will remain limited.44 A programme is only really ready for broad dissemination if it has solid evidence of efficacy and effectiveness, materials and services that facilitate going to scale (i.e., manuals, training and technical support), clear cost information, as well as monitoring and evaluation tools, so that adopting organisations can monitor and evaluate how well the programme works.45 Prinz and Sanders propose that additional standards are needed if programmes are intended to reach whole populations: these include evidence of flexibility, ease of accessibility, cost efficiency, practicality at a population level, and effectiveness in population-level applications.46

Instrument development

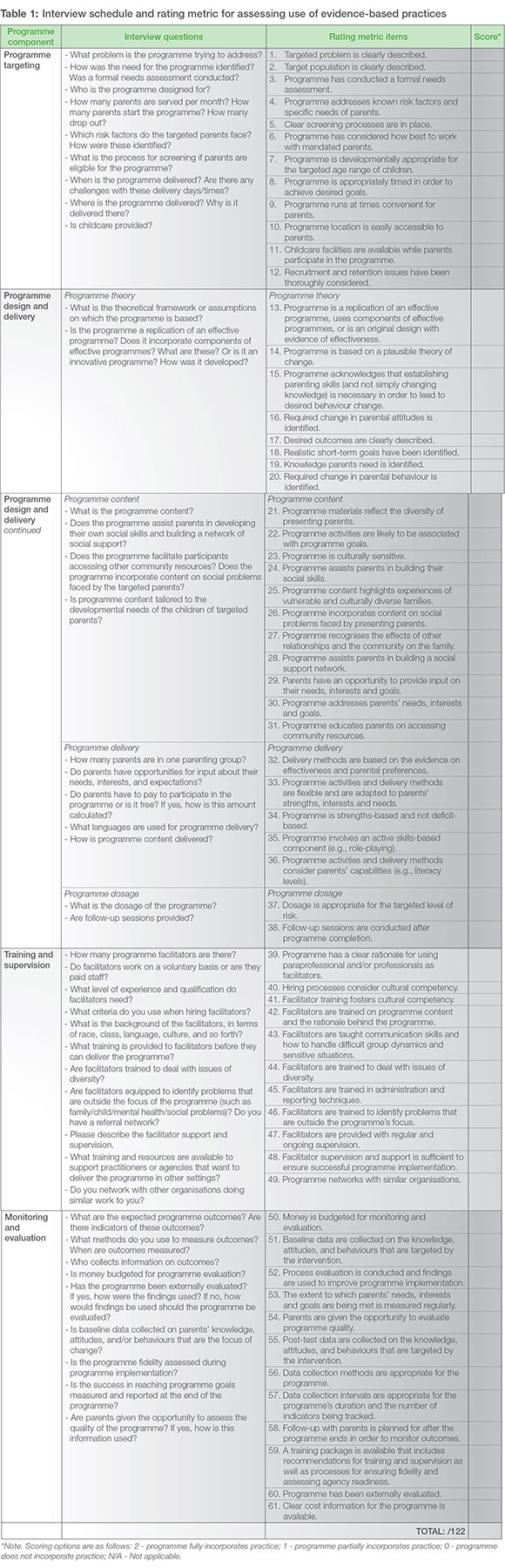

In applying these ideas to parenting programmes in South Africa, we developed a set of interlinked instruments - an interview schedule and rating metric (see Table 1, in which the instruments have been combined) - for assessing the degree to which group-based parenting programmes incorporate the practices discussed above. These instruments were based on two expert-compiled checklists, namely the University of Delaware guide for measuring fit between parent education and support groups with best practice,47 and the Children's Workforce Development Council's Parenting Programme Evaluation Tool48 for measuring alignment with evidence-based practice in early intervention and prevention programmes. Additional information, based on the authors' review of the literature and experience in the parenting programme sector, has been added to these, and distilled into the two instruments: an efficient means to extract information about a programme from programme staff (through the interview schedule), and a means to rank and compare programmes (through the rating metric).

Some of the items in these instruments are specific to parenting programmes, while others are generic to all prevention programmes. We offer the instruments here in the hope that they could be useful to other areas of violence prevention, if a similar process of instrument development is used: the generic items would of course be widely applicable, and a review of the literature in the specific area of violence prevention would yield items that are specific to that area.

After some initial development, the interview schedule was piloted with two parenting programmes in order to determine whether the included questions elicited the desired information. After pilot-testing, additional questions relating to programme cost and to the language used for delivery were added to the schedule.

In order to gain an accurate assessment of a programme, the interview should be conducted with a staff member who has a thorough understanding of both the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention and its delivery -for example, the programme developer, organisational director or programme manager. The length of the interview will depend on the complexity of the programme and the time made available for the interview by the targeted staff member. Once the interview has been completed, the interviewee should be given the opportunity to comment on what has been recorded. This allows the interviewee to add any further information to the schedule, or modify any information the interviewer may have misinterpreted. Interview data should be analysed using content analysis.

In addition to conducting interviews with programme staff, programme materials, including facilitator and parent manuals, handouts and DVDs, should be collected. The type of content covered by programmes can be verified by scrutinising these materials. It also enables the readability of the materials to be assessed, using scales like the Flesch Readability Ease Score and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (available on most of today's word-processing programmes). These scales provide an assessment of the appropriateness of materials for targeted parents in terms of their reading level. This process may be particularly important for programmes implemented in low-income communities where literacy levels may be low.

Once these data have been analysed, a rating of the programme's fit with evidence-based practices can be calculated using the metric, which scores how the programme matches with evidence-based practices. Programmes score one of: 2 (programme fully incorporates practice), 1 (programme partially incorporates practice), 0 (programme does not incorporate practice) or 'not applicable'. Once all statements have been scored, a total rating out of a total of 122 can be calculated.

These instruments are not without their limitations. Firstly, although fairly simple, they can only be administered by someone with adequate knowledge of programme development, monitoring and evaluation. Secondly, the amount of data generated by the interviews can vary considerably between programmes and depends on the interaction between the duration of the interview and the interviewee's understanding of design and evaluation terminology. Considerably more data are typically gained from programmes that have a staff member who is able to commit to a lengthier interview, and who has a good understanding of the necessary terminology. If relevant information is omitted during the interview, it may affect the programme's rating of their fit with evidence-based practice. Furthermore, programmes that do not provide their materials for review cannot be rated on these criteria.

The final limitation is that each item in the metric is given the same weighting, although some are more critical than others. For example, having a plausible programme theory should be given a greater weighting than whether the programme content develops participants' network of social support. Despite this limitation, these instruments still provide a fairly quick and easy means of assessing use of evidence-based practices.

Application to parenting programmes in South Africa

Through snowball and convenience sampling, 21 group-based parenting programmes located across South Africa were identified and included in this study. All these programmes were designed to reduce negative parenting, teach positive parenting strategies, or improve parent-child relationships. They all contained specific parenting components or curricula aimed at changing general parenting knowledge, attitudes or skills.

Three programmes (14%) were developed outside of South Africa, while 18 (86%) were developed in South Africa. In terms of provincial distribution within South Africa, three programmes (14%) were available nationally. Two-thirds of the programmes (n = 14; 67%) were available in more than one province, while the others were only available within one province or community. The Western Cape (n = 16; 76%), followed by Gauteng (n = 11; 52%), had the most programmes, while the Eastern Cape and the Northern Cape (n = 4; 19% respectively) had the least.

Thirteen programmes (62%) were located within the non-profit sector, with the other eight (38%) being commercially run. The former typically served parents from low socio-economic backgrounds, while the latter tended to target parents from upper middle to upper socio-economic backgrounds. There were considerably more urban-based (n = 16; 76%) than rural or mixed urban- and rural-based programmes (n = 5; 24%). Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine the reach of most programmes as they either did not track attendance or did so haphazardly.

A senior staff member, typically the director or programme manager, from each of the 21 programmes was interviewed, either telephonically or in person, using the interview schedule. Interviews lasted between one and three hours. Programme materials, including handbooks and DVDs, were also gathered. Each programme was assessed against the metric by one rater, and, in order to validate the scores, another rater independently rated a subsample of Ave programmes. The inter-rater reliability was found to be 0.62 (Cohen's Kappa; p < 0.001), which is considered an adequate level of agreement49 - this was achieved with minimal training, suggesting that the instrument is simple to use and should transfer to other contexts. As a result, the first rater's ratings were used.

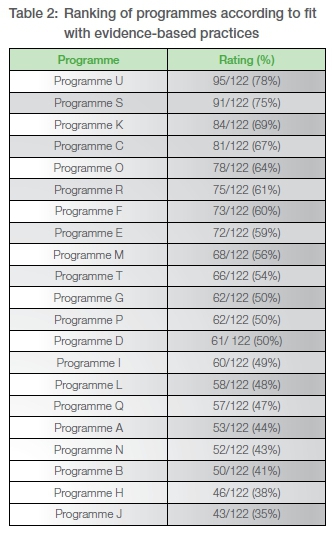

Results showed that none of the 21 programmes was fully aligned with the evidence-based practices identified in the metric (see Table 2). However, 13 programmes incorporated at least half of them, with two having incorporated 72% and 75% respectively. Alignment with evidence-based practice for the remaining eight programmes ranged from between 35% and 49%. The mean across the programmes was 52%.

Despite the generally low uptake of evidence-based practices, an encouraging finding was that most programmes had considered ways of addressing barriers to programme access and participation. For example, programmes serving parents from low socio-economic backgrounds were typically delivered in community venues, such as churches, close to participants' homes. Through locating programmes within served communities, common barriers to engagement, including financial barriers and transport difficulties, were often avoided.

There were, however, specific areas in which the use of evidence-based practices was clearly lacking. For example, only five programmes (24%) had conducted a formal needs assessment, which is concerning as this is a key step in ensuring that the programme is based on an accurate understanding of the target population and context. Programmes that had not conducted a needs assessment often relied on informal contact with community members as a means of assessing need.

Additionally, many programmes did not have a clearly articulated and empirically sound programme theory, which is one of the core building blocks of an effective programme.50 Programmes would be strengthened if they drew on the available evidence base on parenting programmes and other prevention interventions to create a plausible theory of change. This said, there is a need to build this evidence in low- and middle-income countries by conducting evaluations of local programmes, testing cultural adaptations of imported and local programmes, and investigating cultural conceptions of parenting.

Aligned to the lack of developed programme theories was a lack of monitoring and evaluation processes, especially outcome evaluation. Only two programmes (10%) had undergone external evaluation, and because they did not make the evaluation reports available, it is not clear whether these were outcome or process evaluations. A shortage of funding was the main reason stated by programme staff as to why evaluation had not been conducted. High-quality evaluation is expensive, and so funders should be encouraged to include a compulsory evaluation component in their funding allocations.

Lastly, training and supervision for programme facilitators was often inadequate, with only 14 programmes (67%) providing this essential service. This was particularly concerning, as most programmes made use of para-professional staff who possibly require more intensive training and ongoing support and supervision than professionals, especially in terms of understanding the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention and thus the importance of fidelity to the model.

Largely for these reasons, most programmes were not currently evaluable, and therefore none of the programmes was in a position where it could be scaled up successfully.51 In order to increase their likelihood of becoming effective and scalable, it is recommended that these programmes incorporate more of the practices associated with programme success. It is acknowledged, however, that the addition of some of these practices may depend on resources that might not be available, especially within low-resource settings. However, it may be possible to eliminate practices that have been associated with less effective programmes -potentially leading to the cutting of some programme costs.

There is a need to build the evidence base in low-and middle-income countries so that programme developers can draw from these. This can be achieved by conducting rigorous evaluations of local programmes and sharing the results, be they positive, negative or equivocal, within the public domain.52 Programme staff commonly identified a lack of capacity and financial resources as a barrier to conducting evaluation. In order to address this barrier, programmes may benefit from linking with local government and research institutions that may offer assistance in conducting evaluations. As mentioned above, donors also have a role to play in fostering a culture of evaluation by providing the necessary funding, and guiding programme developers and implementers towards appropriate technical assistance.

Implications of these findings

The instruments enabled an understanding of available group-based parenting programmes in South Africa. This understanding can inform the way in which donors and policymakers select programmes to implement, and can support programmes in becoming more effective and scalable by highlighting areas of programme design, delivery, and evaluation that require additional research and strengthening. For example, there is a need to support existing programmes in developing plausible programme theories, providing adequate training and support to facilitators, and setting up monitoring and evaluation systems. Furthermore, once programmes increase their adoption of evidence-based practices, their effectiveness should be tested. If programmes are found to be effective, it is then necessary to investigate how best to take them to scale so that fidelity is maintained.

The approach used in this research can be applied to other violence prevention programmes where little is known about intervention effectiveness. The instruments provide a quick, relatively low-cost means for surveying programmes and identifying promising programmes and areas where programmes need strengthening. They may also be useful during programme development by providing insight into key components that should be included in intervention design and delivery. Content that is specific to parenting programmes can be replaced with that which is relevant to another area (such as youth violence prevention, or elder abuse prevention); much of the content (such as the requirement for needs assessments, or for sound programme theory), however, is generic and applies to all prevention programming.53 It thus provides a basis for national strategies to introduce violence prevention interventions; and for individual programmes to carry out self-assessments prior to engaging in outcome evaluations.

Notes

The authors would like to thank all of the programmes that participated in this research, and the staff members who gave up valuable time to be interviewed and provided us with such useful input. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their suggestions, which have significantly strengthened the article. This research was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of South Africa awarded to the second author. Any opinion, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and the NRF does not accept any liability in regard thereto. inge.m.wessels@gmail.com cathy.ward.sa@gmail.com

1 M Seedat et al., Violence and injuries in South Africa: prioritising an agenda for prevention, The Lancet, 374:9694, 2009, 1011-1022. [ Links ]

2 World Health Organization (WHO), Global status report on violence prevention 2014, Geneva: WHO, 2014. [ Links ]

3 V Farr, A Dawes and Z Parker, Youth violence prevention and peace education programmes in South Africa: a preliminary investigation of programme design and evaluation practices, Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, 2003, http://www.ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/trauma/resrep/violence_prev.pdf. [ Links ]

4 A Gevers and E Dartnell, Violence prevention programme: consideration for selection and implementation, South African Crime Quarterly, 51, 2015, 53-54; [ Links ] D Ghate et al., Key elements of effective practice in parenting support, Youth Justice Board for England and Wales, 2008, http://www.yjb.gov.uk/Publications/Resources/Downloads/Parenting%20source_final%20file.pdf; [ Links ] M Nation et al., What works in prevention: principles of effective prevention programs, American Psychologist, 58, 2003, 449-456. [ Links ]

5 JW Kaminski et al., A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness, Journa of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 2008, 567-589. [ Links ]

6 WHO, Global status report on violence prevention 2014.

7 D Budlender, P Proudlock and S Giese, Funding of services required by the Children's Act, Community Agency for Social Enquiry & Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, 2011, http://www.ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/researchreports/2011/ca_services_funding_may11.pdf [ Links ]

8 Western Cape Government, Integrated Provincial Violence Prevention Policy Framework, http://www.westerncape.gov.za/text/2013/September/violence-prevention-cabinet-policy-final.pdf.

9 PH Rossi, MW Lipsey and HE Freeman, Evaluation: a systematic approach, Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2004. [ Links ]

10 Ibid.

11 Nation et al., What works in prevention.

12 Ibid.

13 JK Orrell-Valente et al., If it's offered, will they come? Influences on parents' participation in a community-based conduct problems prevention program, American Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 1999, 753-783. [ Links ]

14 Ibid.

15 Nation et al., What works in prevention; M Chaffin, B Bonner and R Hill, Family preservation and family support programs: child maltreatment outcomes across client risk levels and program types, Child Abuse and Neglect, 25, 2001, 1269-1289. [ Links ]

16 Rossi, Lipsey and Freeman, Evaluation.

17 Kaminski et al., A meta-analytic review of components.

18 P Moran, D Ghate and A van der Merwe, What works in parenting support?: a review of the international evidence, London: Department for Education and Skills, 2004. [ Links ]

19 Gevers and Dartnell, Violence prevention programme.

20 Kaminski et al., A meta-analytic review of components.

21 Gevers and Dartnell, Violence prevention programme.

22 Nation et al., What works in prevention.

23 M Huser, SA Small and G Eastman, What research tells us about effective parenting education programs, fact sheet, What Works, Wisconsin, Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2008, http://whatworks.uwex.edu/attachment/factsheet_4parentinged.pdf [ Links ]

24 Moran, Ghate and Van der Merwe, What works in parenting support?.

25 A Mejia, R Calam and MR Sanders, A pilot randomised controlled trial of a brief parenting intervention in low-resource settings in Panama, Prevention Science, 16, 2015, 707-717. [ Links ]

26 SM Eyberg et al., Maintaining the treatment effects of parent training: the role of booster sessions and other maintenance strategies, Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 1998, 544-554. [ Links ]

27 J Hutchings et al., A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in Sure Start services for children at risk of developing conduct disorder, British Medical Journal, 334, 2007, 678-682; [ Links ] D Olds, The nurse-family partnership, in NF Watts et al. (eds), The crisis in youth mental health: early intervention programs and policies, Westport: Praeger, 1999, 147-180. [ Links ]

28 D Olds et al., Home visiting by paraprofessionals and by nurses: a randomised, controlled trial, Pediatrics, 110, 2002, 486-496. [ Links ]

29 C Day et al., Evaluation of a peer led parenting intervention for disruptive behaviour problems in children: community based randomised controlled trial, British Medica Journal, 2012. [ Links ]

30 University of Delaware, Measuring the fit with best practices for parent education and support programmes, http://ag.udel.edu/extension/fam/recprac/criteria.pdf.

31 Nation et al., What works in prevention.

32 Gevers and Dartnell, Violence prevention programme.

33 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Guide to implementing family skills training programmes for drug abuse prevention, Vienna: UNODC, 2009. [ Links ]

34 Ibid.

35 Nation et al., What works in prevention.

36 M Little et al., The impact of three evidence-based programmes delivered in public systems in Birmingham, UK, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6, 2012, 260-272. [ Links ]

37 Rossi, Lipsey and Freeman, Evaluation.

38 Gevers and Dartnell, Violence prevention programme.

39 WR Shadish, TD Cook and DT Campbell, Experimental and quasi-experimenta designs for generalised causal inference, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002. [ Links ]

40 M Tomlinson, CL Ward and M Marlow, Improving the efficiency of evidence-based interventions: the strengths and limitations of randomised controlled trials, South African Crime Quarterly, 51, 2015, 43-52. [ Links ]

41 JS Wholey, Evaluability assessment, in JS Wholey, HP Hatry and CE Newcomer (eds), Handbook of practical programme evaluation, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004, 33-62. [ Links ]

42 Juvenile Justice Evaluation Center, Examining the readiness of a program for evaluation, Program Evaluation Briefing Series 6, Washington, DC: Juvenile Justice Evaluation Center Justice Research and Statistics Association, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2003, http://www.jrsa.org/pubs/juv-justice/evaluability-assessment.pdf

43 P Craig et al., Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance, British Medical Journal, 2008, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2769032/. [ Links ]

44 CJ Shapiro, RJ Prinz and MR Sanders, Population-based provider engagement in delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions: challenges and solutions, The Journa of Primary Prevention, 31, 2010, 223-234. [ Links ]

45 BR Flay et al., Standards of evidence: criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination, Prevention Science, 6, 2005, 151-175. [ Links ]

46 RJ Prinz and MR Sanders, Adopting a population level approach to parenting and family support interventions, Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 2007, 739-749. [ Links ]

47 University of Delaware, Measuring the fit with best practices for parent education and support programmes.

48 Parenting Programme Evaluation Tool (PPET), Children's Workforce Development Council, 2001, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/https://www.education.gov.uk/ publications/eOrderingDownload/Parenting%20Programme%20Evaluation%20Tool.pdf.

49 DG Altman, Practica statistics for medical research, London: Chapman & Hall, 1991. [ Links ]

50 Rossi, Lipsey and Freeman, Evaluation.,

51 Flay et al., Standards of evidence.

52 Moran, Ghate and Van der Merwe, What works in parenting support?.

53 Gevers and Dartnell, Violence prevention programme.