Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SA Crime Quarterly

versión On-line ISSN 2413-3108

versión impresa ISSN 1991-3877

SA crime q. no.49 Pretoria jul./sep. 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/sacq.v49i1.2

CHIEF'S JUSTICE?

Chief's justice? Mining, accountability and the law in the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela Traditional Authority Area

Sonwabile Mnwana

Researcher in the Mining and Rural Transformation in Southern Africa (MARTISA) project, Society Work and Development Institute (SWOP), University of the Witwatersrand. mnwanasc@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Drawing on research conducted in the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela traditional authority area in North West Province, this article explores how the expansion of platinum mining on communal land is generating resistance to a local chief. The point at issue is the chief's refusal to account for the mining revenues and business transactions that his traditional authority manages on the community's behalf. The article argues that the North West High Court's interpretation of customary law not only leaves the chief's unaccountability unchecked but also endorses the punishment of village activists who call the chief to account. Hence it remains extremely difficult for ordinary rural residents to challenge the chief to account for vast mineral revenues that he controls on behalf of their communities. Consequently rural anti-corruption activists are losing faith in the justice system.

Unlike the gold industry, which largely affected urban industrial centres, the platinum industry has shifted the geographical focus of post-apartheid mining. The vast platinum-rich rock formation of the Bushveld Complex primarily spreads beneath rural communal land under the political jurisdiction of traditional (formerly known as 'tribal') authorities.1 In the past two decades these densely populated rural areas have become the focus for the expansion of the platinum industry, particularly in the North West and Limpopo provinces. Having previously fallen under the 'independent homelands' of Bophuthatswana and Lebowa respectively, they bear the hallmarks of the apartheid order: extreme poverty, massive unemployment, poor education and a paucity of basic public services. Major operations of the world's largest platinum producers such as Anglo American Platinum Limited (Amplats), Impala Platinum Holdings Limited (Implats) and Lonmin Plc (Lonmin) compete for space with communities in these overcrowded areas.2

The expansion of the mining industry in communal areas coincides with post-apartheid attempts to redefine residents in these areas, through law, as subjects of 'traditional communities' (or 'tribes') under chiefs. Legislation that has been enacted since the early 2000s has not only legitimised the mediation of mine-community relationships by traditional leaders, but has also significantly enhanced the powers of chiefs in South Africa. Although the post-1994 African National Congress (ANC) government at first vacillated about defining and codifying the powers and status of chiefs, it eventually passed legislation that significantly increased the powers of chiefs in rural local governance. The Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 2003 (Act 41 of 2003, or the TLGFA)3 is the main piece of legislation in this regard.

The TLGFA re-enacts traditional (tribal) authorities to preside over precisely the same geographic areas that were defined by the apartheid government.4

Among other things, the Act enables chiefs and their traditional councils to be granted power over the administration and control of communal land and natural resources, economic development, health and welfare, and to administer justice.5 As such, not only does this Act impose the former colonial tribal authority demarcations on rural citizens, it also promotes a controversial governance role for chiefs. Other controversial laws that, so far, have been successfully resisted by rural citizens include the Communal Land Rights Act 2004 (Act 11 of 2004)6,7 and the Traditional Courts Bill.8,9

Post-apartheid laws regulating mineral rights, particularly the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act 2002 (Act 28 of 2002, or the MPRDA) and its accompanying regulations, also drive the inclusion of traditional communities in South Africa's platinum industry. In seeking to redress past injustices by transforming relationships between the mining companies and local communities, this legislation has adopted a range of measures, including continued royalty payments, black economic empowerment (BEE) mine-community partnerships, and social labour plans, as requirements for mining companies. The state has encouraged communities who previously received royalty compensations for loss of land due to mining, to convert their royalties into equity shares. Consequently, with the state's support, chiefs, as assumed custodians of communal resources, have become mediators of mineral-led development and mining deals.

This means that traditional communities' interactions and engagements with mining companies are mediated and controlled by local chiefs. As assumed custodians of rural land and other tribal properties, chiefs enter into mining contracts and receive royalties and dividends on behalf of rural residents who live in the mineral-rich traditional authority area. This traditional-elite mediated model of community participation in the mining industry10 has received increased media attention,particularly since the 2012 Marikana massacre.11, 12 In the face of protracted labour unrest in the platinum sector, the dominant view propagated by the government, mining companies and the chiefs is that tribal-elite mediated community control of mineral revenues is crucial for congenial relations within the rural-based platinum sector. For instance, Kgosi (Chief) Nyalala Pilane of the Bakgatla 'tribe' has recently argued that,

[a] local community with strong leadership is an [asset] to a mining company, providing easy access to labour and lowering costs ... Companies . can approach these communities in a structured way . it's a win-win situation for everyone.13

Thus chiefs see themselves as legitimate mediators and gatekeepers through whom mining capital can gain 'easy access' to cheap local labour and communal land. However, recent research has shown that this model has not yet led to tangible benefits for community members, instead it has enhanced the power of the chiefs and caused a lack of transparency, unaccountability, heightened inequality, deepened poverty and local tensions.14

Post-apartheid laws regulating and governing traditional leadership and mining reform have been criticised for promoting exclusion and corruption by using 'distorted constructs of custom' to 'impose contested identities' and 'undermining [rural residents'] capacity to protect their land and . mineral rights'.15

However, is custom really distorted in these postapartheid arrangements? Recognised by the Constitution,16 customary law in South Africa falls into two main categories: the 'official' and the 'living' law. 'Official' customary law is a product of the state and legal experts,17 while ‘“living" law refers to the law actually observed by the people who created it'.18 Official customary law is a product of colonial formalisation of indigenous peoples' law, which imposed rigid, Western, rule-oriented conceptions of law and order. Living law, on the other hand, evolves organically out of ever-changing African sociocultural 'processes' of dispute resolution.19 Thus it is through codification that authentic 'living law' became distorted. This process of 'formalisation' of custom enhanced the power of chiefs during colonial and apartheid periods. For Mamdani, customary law became both 'all embracing' and divisive. It 'embraced' under the power of chiefs 'previously autonomous social domains [among others] the household, age sets, and gender'. Yet, the purpose of customary law, argues Mamdani, 'was not about guaranteeing rights, it was about enforcing custom. It was not about limiting the power [of chiefs], but about enabling it'.20

The Constitution of South Africa mandates the courts to:

[A]pply customary law when that law is applicable, subject to the Constitution and any legislation that specifically deals with customary law.21

However, this mandate seems difficult to realise in the light of post-1994 legislation that reinforces the apartheid-style power and authority of chiefs. Claassens cautions:

[T]o determine the content of customary law by standards of 'formal' law is to apply a distorted paradigm.22

This article demonstrates how judgements by the North West High Court not only promote these distorted versions of custom, but also bolster and protect the power of the chiefs. Drawing on research conducted in the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela traditional authority area, North West, the article argues that the court's interpretation of customary law not only leaves the chief's unaccountability and power abuse unchecked, it also endorses the punishment of village activists who call the chief to account. Hence it is extremely difficult for ordinary rural residents in the platinum belt to challenge the chief and hold him to account for the vast mineral revenues under his control on behalf of their communities.

The empirical section of this article begins with a summary of local resistance against the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela chief, who refuses to be held accountable to his community about mining revenues. This is followed by a discussion of selected court judgements, focusing particularly on the interpretation of customary law.

A note on data collection

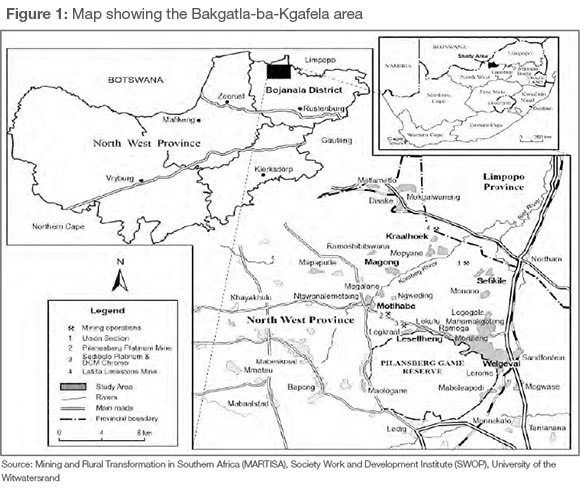

This article is based on a study that began in August 2009, when I spent three months collecting ethnographic data in the villages of Moruleng and Lesetlheng.23 I returned to the research site again in July 2013 and spent two months conducting another round of field research, focusing on platinum mining and evolving forms of struggles in the villages of Lesetlheng, Motlhabe and Sefikile (See Figure 1). The study is still in progress and I continue to make sporadic follow-up research visits to the study area. The ethnographic material presented here is based on selected semi-structured key-informant interviews with village activists in the selected villages.24 This selected ethnographic material is corroborated by reference to selected archival documents in the South African National Archives in Pretoria.

The Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela traditional authority area

The Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela are a Setswana-speaking traditional authority community under the leadership of Kgosi Nyalala Pilane, and they occupy one of the largest communal areas in North West. Their 32 villages (see Figure 1) are spread over a vast area of more than 35 farms in the Pilanesberg region, about 60 km north of the town of Rustenburg, and fall under the Moses Kotane Local Municipality (MKLM). With approximately 300 000 residents, the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela area is the epitome of a prominent tribal authority territory with vast mineral resources.25

Resistance to the chief’s control over mining revenues

The platinum boom, which began in the early 1990s, ushered the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela area to centre stage. Over the past two decades, several mining operations have developed in Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela territory. On behalf of the residents in the area under his jurisdiction, Pilane has entered into numerous deals and concessions with the mining companies and other investors.26 As a result of these deals, the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela community has become a huge business empire worth approximately R15 billion.27 This has elevated the chief's power and status.

There is mounting resistance by members of the community to Pilane, due to his lack of transparency and accountability in corporate dealings, and allegations of corruption against him. The contribution by Boitumelo Matlala in this issue covers in detail these struggles and their different trajectories. The investments that the kgosi has entered into through contracts with mining companies are legion. He is the director of numerous companies in a complex network that bear the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela name. Some village groups contest these mining contracts that are signed by the chief. They argue that their forefathers bought the mineral-rich farms as private properties and that they should never have become tribal land.

In 2006 the regional court at Mogwase convicted Pilane and his close associate, Koos Motshegoe, on more than 40 counts of fraud and theft.28 The fraud charges centred on the allegation that in 1998 Pilane signed three loan agreements to the value of R13 million with the Land and Agricultural Bank of South Africa on behalf of the community, but without a community mandate. He pledged to repay this money through the annual royalties that the tribal authority receives from Anglo American Platinum. The regional court found that Pilane 'was not authorised to act on behalf of the tribe to enter into a loan agreement'.29 Subsequently the court denied the kgosi and his co-accused the right to appeal. His lawyer filed a petition to the then Judge President of the North West High Court, who in 2009 granted the chief and his co-accused permission to appeal against their criminal convictions.30

In September 2010 the high court upheld the application and acquitted Pilane and his co-accused of all criminal charges.31 This ruling surprised and devastated the villagers. The blow was even more severe for members of the Concerned Bakgatla Anti-Corruption Organisation (COBACO). COBACO, a village-based grassroots movement, had worked hard, with limited resources, to get the chief convicted. It had taken it from 1997 to 2006 to Anally get Pilane to court. One of the active members of COBACO explained:

After that [Pilane's acquittal] we did nothing. We were there but we did not communicate, we did not hold meetings, things went quiet.32

Through summaries of selected court judgements, the next section demonstrates how the court's interpretation of custom leaves the chief's unaccountability unchecked in the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela area. The 1950s judgement is included, not to compare judgements during apartheid with postapartheid judgements, but to provide an indication of how the courts' interpretation of customary law in the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela community still results in punishment of the chief's opponents. Ironically, this situation continues in the post-1994 democratic era.

The law: a chief’s weapon for punishing ‘troublemakers’?

During the rule of Kgosi Tidimane Pilane - Pilane's predecessor - there were sporadic instances of resistance against the traditional authority. In one instance in 1953, Kgosi Tidimane imposed a levy of one ox per person on every adult male member of his tribe for the purchase of the farms Middelkuil No. 564 and Syferkuil No. 372. The combined price for both farms was #14 000.33 Those who could not offer oxen were obliged to pay #15 per person. In June 1956 a group of village residents, led by Jacob Pilane, a village activist and relative of the chief, filed a court petition accusing the chief for failing to account for the money he collected and 'wrongfully and unlawfully using and appropriating tribal funds for [his] personal benefit'.34

The hearing took place at the Transvaal Supreme Court in Pretoria on 28 June 1956. Jacob Pilane was listed as the only 'petitioner' against Tidimane. Judge C Bekker dismissed Jacob's application on 16 August 1956. His judgement was primarily based on the argument that the chief had no responsibility to account 'to anyone of his individual subjects' concerning the tribal accounts and that Jacob, although a member of the tribe, did not have locus standi to file a court application against the chief. Bekker continued:

[I]n native law the chief, in circumstances such as the present is held accountable only to the tribe acting in, or through a lekgotla or tribal meeting ... the petitioner [Jacob], in his private capacity is not, in my view of the matter entitled to the relief he claims - reliefs personal to himself and not to the tribe.35

The judge also awarded costs against Jacob. This verdict was not the last of his troubles. The chief's loyalists in Moruleng harassed his family for challenging the chief and accused him of trying to overthrow the chief. Since the judge awarded Tidimane the costs in the case, this gave him more ammunition with which to punish Jacob. Jacob was unable to pay the legal costs, so Tidimane sent a group of men to his home to confiscate his cattle and agricultural tools by force. When this happened Jacob was in Swaziland, where he worked as a chef. One of his sons, who witnessed these events, said:

The year was 1956 and I was doing Sub B when they came and took all my father's possessions. They came looking for my father's cattle. They took three cows together with all the ploughing equipment and left. They sold them to a white farmer called Piet Koos . in Pilanesberg.36

Jacob never recovered his confiscated property.

The judgement against Jacob Pilane relied significantly on a distorted version of 'official' custom, which absolved chiefs from accounting to individual community members, thus providing them with enormous leverage to manipulate the downward accountability processes. As the only person entitled to call meetings (according to the 'official custom'), if a chief wants to avoid accountability he can simply refuse to convene community meetings.

The courts' use of distorted 'official custom' continues in the post-apartheid democratic era. Over the past decade, Pilane has filed several court interdicts against a number of villagers who have challenged his power over the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela community. This has intensified as more and more community members display displeasure with the chief's unilateral control over mining revenues.

In May 2008 Pilane filed an urgent court interdict at the North West High Court against a group of residents led by David Pheto. Identifying themselves as the 'Royal House', Pheto and other disgruntled community leaders had called an urgent general community meeting (a Kgotha-Kgothe) in order to oppose the mining transactions that the chief was about to sign on behalf of the community. The meeting was to be held on 21 May 2008. The dissenting group of residents also wanted to preempt another general meeting called by the chief on 28 June 2008 to co-opt the community into endorsing a murky mining transaction. Through this meeting Pilane intended to obtain a tribal resolution for a transaction between Itereleng Bakgatla Mineral Resources (Pty) Ltd (IBMR) (owned by the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela) and Barrick Platinum South Africa (Pty) Ltd (Barrick), a subsidiary of Barrick Gold Corporation.37 The villagers opposed this transaction, mainly because they felt marginalised. They felt that the chief was unilaterally signing a mining contract that undermined their land rights without fully involving them.38

At the time, Pilane was facing a case of numerous instances of fraud and theft.39 Pheto and other villagers demanded that he step down from his position. In response, Pilane interdicted Pheto and five other leaders of the dissent 'from interfering with a ... general meeting which was to be held on 28 June 2008'.40

In the North West High Court, Judge AM Kgoele consolidated the two interdicts and handed down the judgement, confirming both the interim interdicts by the chief against Pheto and others on 3 December 2008.41 The central argument in the judge's decision was that Pheto and five other community leaders did not have locus standi to call meetings of the tribe or to mobilise for the removal of Pilane from his position. Kgoele dismissed their claim that they were members of the 'Royal House' and refused them leave to appeal. The Supreme Court of Appeal also turned down their request for leave to appeal this decision.

Subsequent judgements at the North West High Court have reinforced Kgoele's decision. This has helped to suppress opposition against Pilane. For instance, in September 2011 Judge RD Hendricks confirmed an interdict by Kgosi Nyalala Pilane against Pheto and other leaders, preventing them from calling community meetings. In line with previous judgements and the North West High Court, the judge found that Pheto and others were not members of the 'Royal Family', therefore they did not have locus standi to call meetings or to represent any group of villagers in Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela territory.

Hendricks imposed punitive costs on Pheto and his fellow dissenters. He averred:

... it is quite apparent that the [Respondents are doing everything within their means to unseat and undermine the authority of the [a]pplicants [Kgosi Nyalala and the Traditional Council] and to litigate as often as possible in an attempt to create confusion within the tribe. This behaviour borders on being vexatious. This, to my mind, calls for a punitive costs order.42

In other cases involving local activists against Pilane, decisions at the North West High Court were no different. The court's decisions continue to endorse the version of custom that ossifies the chief's power over communal property and endorses the tribal authority as the only legitimate authority with locus standi to represent village residents. For instance, in a land dispute case between Pilane and a group called Bakgatla-ba-Sefikile Traditional Community Association (BBSTCA),43 Judge MM Leeuw, citing the Constitution and customary law, argued:

In this matter I am enjoined by the Constitution to recognise that land that is held by the Kgosi or traditional leader on behalf of a tribal community should be dealt with in terms of legislations that have been enacted for the purpose of regulating amongst others, the ownership thereof as well as the role and powers of the traditional leaders.44

The judge dismissed the application of the BBSTCA with costs.

Also at the North West High Court on 30 June 2011, Judge AA Landman's judgement upheld Pilane's interdicts against Mmuthi Pilane and Reuben Dintwe. Mmuthi Pilane and Dintwe are two activists leading a secession attempt by the residents of Motlhabe village. The judge argued:

Any action by a parallel but unsanctioned structure that is neither recognised by law or custom seeking to perform or assume functions that are clearly the exclusive preserve of recognised authorities ought to incur the wrath of law.45

The North West High Court and the Supreme Court of Appeal denied Mmuthi Pilane and Dintwe leave to appeal against this judgement. The lawyers who represented the two activists took the matter to the Constitutional Court, which set aside the three interdicts in February 2013, mainly on the basis that these 'interdicts adversely impact on the applicants' rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly'.46 The Constitutional Court judgement was a landmark victory for traditional communities: it affirmed the freedom of expression, assembly and association of rural residents. It should be cautioned, however, that the setting aside of the three interdicts against Mmuthi Pilane and Dintwe (also mentioned in Monica de Souza's contribution in this edition) did not reverse the previous judgements or the cost orders issued against Pheto and other village activists.

Pheto’s punishment and dwindling faith in the justice system

As a result of one of several punitive costs orders, Pheto has suffered great personal loss, including loss of his livelihood. On 18 October 2013 the North West High Court issued a 'Writ of Execution' of punitive costs against Pheto. According to this document Pheto owes Pilane R372 204,30 in legal costs. This originated from Kgoele's judgement in December 2008 when she confirmed two of Kgosi Nyalala's interdicts and imposed punitive costs on Pheto and the six other respondents.47 The baffling irony remains the fact that, out of seven respondents, the North West High Court has targeted Pheto alone with the execution of legal costs: the amount is not divided among the court respondents. Obviously, Pheto perceives himself as being targeted as a leader of the 'rebellion':

Why did the apartheid government kill Steve Biko? Why did they arrest Nelson Mandela? It's because these leaders were causing trouble to that oppressive regime. The punitive costs are targeting the 'troublemakers'. That is why I am the only person who is being punished.48

Before this incident Pheto was running a legal practice in Mogwase, about 10km from Lesetlheng village where he lives with his family. The sheriff has since attached all his office equipment and Pheto has not been able to continue with his legal practice. The small butchery that he had been running with his siblings in Moruleng was also closed down after the sheriff attached all the equipment inside. Pheto and his ailing mother have fought to defend the property at his home in Lesetlheng from being attached.

Pilane's numerous court applications against Pheto and other leaders have also contributed towards Pheto's financial demise. As one of the few villagers who had some kind of income in the impoverished Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela territory, Pheto and other leaders had to pay the lawyers who represented them out of their personal funds. It is therefore unsurprising that some of the community activists who were previously with Pheto in these court battles against the chief have now abandoned the struggle. Some have even shifted allegiances to join forces with Pilane, and now occupy senior positions in the traditional political hierarchy. These positions are allegedly accompanied by good salaries and other benefits.

It is no exaggeration to argue that court cases and costs orders have, even if accidentally, functioned as a potent tool for chiefs to suppress opposition and constrain the rights of rural villagers, especially in the face of rural-based platinum mining expansion in North West. This instils fear in the villagers and prevents them from challenging the power of the chief. It is against the backdrop of the North West High Court's judgements that Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela activists have experienced a loss of faith in the justice system. The evident difficulties in removing the chief's control over the mining revenues have led to some nicknaming him 'Mr Untouchable'.49

The situation is aggravated by the fact that villagers have had to use their meagre financial resources in their efforts to obtain justice. With a despairing tone, Pheto described the situation:

The chief uses tribal funds to enjoy the luxury of hiring the most expensive legal expertise in the land to fight against ordinary rural community members like us. We act on behalf of the tribe. The police arrest us. The courts target us with punitive costs so that the chief can hold us in subservience. The grand apartheid is not yet over. We don't have money to hire big lawyers and private investigators.

We have tried everything we could to defend our rights from the chief and the vultures [mining companies] from all over the world who converge on our forefathers' land to prey on the poorest of the poor. We've been fighting for so long without any help from the current government. Time is moving fast. You grow up every day, then you get sick and you die.50

As pointed out earlier, the leaders of COBACO have not only struggled to maintain their support in their villages after losing the appeal case against the chief at the North West High Court in 2010, but their faith in the justice system has also dwindled.

Conclusion

Using the Bakgatla-ba-Kgafela community as a case study, this article has demonstrated a threefold paradox. Firstly, it has revealed that vast mineral wealth has enhanced the chief's power. Secondly, it has shown that it remains extremely difficult for ordinary villagers to hold the chief to account about communal resources. This hardship is exacerbated by the courts' application of distorted custom, which punishes villagers through costs orders. This means that marginalised rural residents are afraid of challenging their chiefs, and diffuses resistance to unaccountable traditional authorities. The chief also uses tribal finances generated through platinum mining to suppress resistance and intensify his hold over mineral revenues. Thirdly, the general lack of faith in the justice system must be understood against the backdrop of this process of marginalisation and punishment. Although it is impossible to generalise from just one case, one can still argue that unaccountability is likely to continue in the rural platinum belt as long as the interpretation of custom applied by the North West High Court functions as a tool for unaccountable chiefs to punish villagers who challenge them.

Such a phenomenon reveals a serious deficit in the current democratic order: unelected traditional leaders champion mineral-led development with very limited accountability measures. As shown in this article, the court's interpretation of custom makes it even more difficult for villagers to hold the chief to account.

Notes

1 The establishment of traditional authority areas in South Africa owes much to several pieces of colonial legislation, including the 'Native' Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 and the Bantu Authorities Act 1951 (Act 68 of 1951, or BAA).

2 Other communities with stakes in platinum mining in North West include the Bafokeng, Bakubung ba Rutheo, Bapo-ba-Mogale and baKwena ba Mogopa. Traditional authorities mediate the transactions between these communities and mining companies. Details of these transactions are complex and beyond the scope of this article.

3 Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act 2003 (Act 41 of 2003); Pretoria: Government Printers.

4 A Claassens, Resurgence of tribal levies: a double taxation for the rural poor, South African Crime Quarterly 35 (2011), 14. [ Links ]

5 See Section 20 of the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act (TLGFA).

6 Communal Land Rights Act 2004 (Act 11 of 2004), Pretoria: Government Printers.

7 Rural communities successfully opposed this Act on the basis that it undermined their private property rights enshrined in the Constitution and unfairly leveraged the powers of the traditional councils over vast areas of communal land. See Tongoane and Others v Minister for Agriculture and Land Affairs and Others (CCT 100/09) [2010] ZACC 10 (11 May 2010).

8 Traditional Courts Bill 2008 (Bill 15 of 2008), published in Government Gazette No. 30902, 27 March 2008, http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/tradcourts/B15-2008.pdf (accessed 12 April 2012).

9 S Mnisi, The Traditional Courts Bill: controversy around process, substance and implications, South African Crime Quarterly 35 (March 2011), 3-10. [ Links ]

10 S Mnwana, Are communities benefiting from mining? Bafokeng and Bakgatla cases, South African Labour Bulletin 37(3) (2013), 30-33. [ Links ]

11 For details of the Marikana massacre see P Botes and N Tolsi, Marikana: one year after the massacre, Mail & Guardian Marikana, http://marikana.mg.co.za/ (accessed 12 September 2014). [ Links ]

12 The mine labour issues are beyond the scope of this article.

13 N Grove, Traditional communities should be seen as partners, not rivals, Mining Weekly, 3 February 2014, http://www.miningweekly.com/article/traditional-communities-should-be-seen-as-partners-not-rivals-to-mining-cos-bakgatla-chief-2014-02-03 (accessed 7 February 2014). [ Links ]

14 S Mnwana, Participation and paradoxes: community control of mineral wealth in South Africa's Royal Bafokeng and Bakgatla Ba Kgafela communities, PhD Thesis, University of Fort Hare, 2012. [ Links ]

15 A Claassens and B Matlala, Platinum, poverty and princes in post-apartheid South Africa: new laws, old repertoires, New South African Review 4 (2014), 116. [ Links ]

16 The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa No. 108 of 1996, Section 211, Pretoria, Government Printers.

17 T Bennett, Official vs living customary law: dilemmas of description and recognition, in A Claassens and B Cousins (eds), Land power and custom: controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act, Cape Town: UCT Press, 2008. [ Links ]

18 Ibid., 138.

19 JL Comaroff and S Roberts, Rules and processes. A cultural logic of dispute in an African context, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981; [ Links ] see also M Mamdani, Citizen and subject: contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. [ Links ]

20 Mamdani, Citizen and subject, 110.

21 The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Section 211 (3).

22 A Claassens, Customary law and zones of chiefly sovereignty: the impact of government policy on whose voices prevail in the making and changing of customary law, in Claassens and Cousins (eds), Land power and custom, p. 362. [ Links ]

23 This was for the author's PhD project, which he completed in 2012.

24 So far, 87 interviews have been conducted with more than 100 respondents.

25 As is the case in many rural areas in South Africa, the relationship between the Bakgatla traditional authority and the MKLM has not been smooth. This can be attributed largely to the lack of clarity about the role of traditional leaders in 'developmental' local governance. See T Binns et al, Decentralising poverty? Reflections on the experience of decentralisation and the capacity to achieve local development in Ghana and South Africa, Africa Insight 35(4) (2005), 28.

26 These investors include Anglo American Platinum, Platmin Limited, Pallinghurst Resources Limited and the Industrial Development Corporation.

27 G Khanyile, Bakgatla tribe men facing corruption probe, iol, 14 October 2012, http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/north-west/bakgatla-tribe-men-facing-corruption-probe-1.1402519#.VCA4PPmSy8A (accessed 12 July 2013).

28 National Director of Public Prosecutions v Pilane and Others (692/06) [2006] ZANWHC 68 (16 November 2006).

29 S v Pilane and Another (CA 59/2009) [2010] ZANWHC 20 (17 September 2010).

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Interview, Mogwase, 19 July 2013.

33 Pretoria National Archives, PTD, Vol. 0, Ref. 1442/1956.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 S Pilane, interview, Moruleng, 2 November 2013.

37 Barric owned 10%, which it inherited when it acquired and integrated more than 80% of Placer Dome shares in 2006. The Bakgatla, through their holding company called Itereleng Bakgatla Mineral Resources (Pty) Ltd) (IBMR), held 90% of the Sedibelo Project.

38 Interview, Lesetlheng, 07 August 2013.

39 As mentioned earlier, these are the charges that were brought to the Mogwase Magistrate's Court by the COBACO members.

40 Pilane and Another vs Pheto & 6 Others (1369/2008) [2008] ZANWHC (03 December 2008).

41 Ibid.

42 Pilane and Another vs Pheto & 5 Others (582/2011) (19 April 2012), para 55.

43 Claiming ownership of the mineral-rich farm Spitskop 410 JQ. Village-level disputes, whether over land, power or otherwise, are closely linked to struggles over mining revenues.

44 Bakhatla Basesfikile Community Development Association and Others v Bakgatla ba Kgafela Tribal Authority and Others (320/11) [2011] (1 December 2011), para 42.

45 Pilane and Another v Pilane and Another (263/2010), (30 June 2011), para 21.

46 Pilane and Another v Pilane and Another (CCT 46/12), (28 February 2013), para 70.

47 See Pilane and Another vs Pheto & 6 Others.

48 D Pheto, Lesetlheng, interview, 13 June 2014.

49 Informal conversation, Moruleng, 28 July 2013.

50 Ibid.